Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

European Health Insurance Card

View on Wikipedia| European Health Insurance Card | |

|---|---|

Example of a Slovenian EHIC card | |

Validity of EHIC cards | |

| Type | ID-1 |

| Issued by | Member states of the European Economic Area[a][1] Switzerland United Kingdom[b][2] |

| First issued | 1 June 2004 |

| Purpose | Access to free or reduced cost health services in any EEA member state, Switzerland and the United Kingdom |

| Valid in | European Economic Area Switzerland United Kingdom[c] |

| Eligibility | EEA, Swiss or UK residency[d] |

| Cost | Free |

| European Union decision | |

| Text with EEA relevance | |

| |

| Title | Decision No 189 of 18 June 2003 aimed at introducing a European health insurance card to replace the forms necessary for the application of Council Regulations (EEC) No 1408/71 and (EEC) No 574/72 as regards access to health care during a temporary stay in a Member State other than the competent state or the state of residence [3] |

|---|---|

| Made by | The Administrative Commission |

| Journal reference | [1] |

| Current legislation | |

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) is issued free of charge to anyone who is insured by or covered by a statutory social security scheme of the EEA countries or Switzerland and certain citizens and residents of the United Kingdom. It allows holders to receive medical treatment in another member state in the same way as residents of that state—i.e., free or at a reduced cost—if treatment becomes necessary during their visit (for example, due to illness or an accident), or if they have a chronic pre-existing condition which requires care such as kidney dialysis. The term of validity of the card varies according to the issuing country. The EEA countries and Switzerland have reciprocal healthcare arrangements with the United Kingdom, which issues a UK Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC) valid in the EEA countries and, in most cases, in Switzerland.[4]

The intention of the scheme is to allow people to continue their stay in a country without having to return home for medical care, and does not cover people who have visited a country for the purpose of obtaining medical care, or non-urgent care that can be delayed until the individual returns to their home country (for example, most dental care). The costs not covered by self-liability fees are paid by the issuing country, which is usually the country of residence, but may also be the country from which the patient receives the most pension.[5] The card only covers healthcare which is normally covered by a statutory health care system in the visited country; additional costs can be met by taking out travel insurance.

The format of the EHIC complies with the ID-1 format, i.e. the size of most banking cards and ID cards (53.98 mm high, 85.60 mm wide and 0.76 mm thick).[6]

History

[edit]The card was phased in from 1 June 2004 and throughout 2005, becoming the sole healthcare entitlement document on 1 January 2006.

It replaced the following medical forms:

- E110 – For international road hauliers

- E111 – For tourists

- E119 – For unemployed people/job seekers

- E128 – For students and workers in another member state

Territorial applicability

[edit]The card is applicable in all French overseas departments (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Réunion, and French Guiana) as they are part of the EEA, but not non-EEA dependent territories such as Aruba, or French Polynesia.[7] However, there are agreements for the use of the EHIC in the Faroe Islands and Greenland,[8] even though they are not in the EEA.

Personal eligibility

[edit]The card exists because the right to health care in the European Union is based on the country of legal residence, not the country of citizenship. Therefore, a passport is not enough to receive health care. It is however possible that a photo ID document is asked for, since the European Health Insurance Card does not contain a photo.

In some cases, even if a person is covered by the health insurance of an EU country, one is not eligible for a European Health Insurance Card. For instance, in Romania, a person who is currently insured has to have been insured for the previous five years to be eligible.[9]

Third party application processors

[edit]European Health Insurance cards are provided free to all legal residents of participating countries. There are however various businesses who act as non-official agents on behalf of individuals, arranging supply of the cards in return for payment, often offering additional services such as the checking of applications for errors and general advice or assistance.[10] This has proved extremely controversial. In 2010 the British government moved against companies that invited people to pay for the free EHIC, falsely implying that through payment the applicant could speed up the process.[11][12]

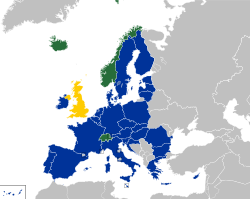

Participating member states

[edit]As of 2021, 31 countries in Europe participate: the 30 member states of the European Economic Area (EEA) plus Switzerland. This includes the 27 member states of the European Union (EU) and 4 member states of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).[13]

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom was a participant in the scheme as a member of the European Union until its withdrawal from the union. It continued to participate provisionally until the end of the Brexit transition period on 31 December 2020.

The EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement grants continued reciprocal healthcare access between the EU and the UK. EU citizens can continue to use their EHIC within the UK,[14] while EHIC in the UK was replaced by a UK Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC).[15][16] Since 2022, some UK citizens and permanent residents are eligible for a new UK-issued EHIC valid for visits to these countries as well as to Switzerland.[17][4] Eligible persons are those who meet one of the following criteria:[18]

- those living in the European Union, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, or Liechtenstein, and have been since before 1 January 2021 with a registered S1, E121, E106 or E109 form issued by the UK

- those living in the EU, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, or Liechtenstein, since before 1 January 2021 with an A1 issued by the UK

- those who are a national of the EU, Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, or Liechtenstein who have legally resided in the UK since before 1 January 2021 and are covered under the Withdrawal Agreement; one may not be covered if they also a UK national or if they were born in the UK

- those who are a family member or dependant of an entitled individual already listed

- those who fall under the court rulings Chen v Home Secretary(UK)[19] or Bashar Ibrahim and Others v Bundesrepublik Deutschland[20] or their carer

During its participation in the scheme, EHIC access covered the British overseas territory of Gibraltar. The crown dependencies of the Channel Islands and Isle of Man were not covered by the EHIC as they were never members of the EU and EEA, and their residents were not eligible for EHICs.[21]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The legal acquis is identified as EEA-relevant by the EU, and is incorporated into the EEA Agreement (by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway).

- ^ Under the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement, the UK continues to issue EHIC to certain individuals who gained entitlement before 1 January 2021.

- ^ Only EU member state-issued EHIC are valid after 31 December 2020. EHIC issued by EFTA members may remain valid where the individual has an ongoing relationship with the UK that started before 1 January 2021.

- ^ Only EU/EFTA citizens, UK state pensioners, frontier workers, workers posted abroad and students studying in the EU on or before 31 December 2020 and eligible family members resident in the UK are entitled to apply for an EHIC.

References

[edit]- ^ "Brexit : De la paperasse et des coûts supplémentaires en vue pour les Britanniques". Le Monde.fr. 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Get healthcare cover for travelling abroad". nhsbsa.nhs.uk. NHS Business Services Authority. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ^ "EUR-Lex - 32003D0751 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Healthcare for UK nationals visiting the EU". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ^ "Are foreigners really gaming the NHS to pay for their medical treatment abroad?". Guardian. 11 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- ^ DECISION No S2 of 12 June 2009 concerning the technical specifications of the European Health Insurance Card

- ^ "UK FCO Travel Advice: French Polynesia". Fco.gov.uk. 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- ^ "UK FCO Travel Advice: Denmark". Fco.gov.uk. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- ^ "Cardul european de asigurări de sănătate, eliberat gratuit". Libertatea.ro. 2009-08-01. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- ^ "Third Party Application Processors". 2016-09-02. Archived from the original on 2020-07-29. Retrieved 2016-06-03.

- ^ "BBC News - European health card scam stopped by OFT". Bbc.co.uk. 2010-08-10. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- ^ "Consumers warned to be search engine savvy – Consumer Focus Wales". Consumerfocus.org.uk. 2011-06-22. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- ^ "European Health Insurance Card". European Commission. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- ^ "Press corner".

- ^ "Brexit: EU diplomats briefed on Brexit trade deal". BBC News. 25 December 2020.

- ^ "Apply for a free European Health Insurance Card (EHIC)". nhs.uk. 2018-08-15. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ^ "Health - Switzerland travel advice".

- ^ "Applying for healthcare cover abroad (GHIC and EHIC)". nhs.uk. 2021-01-11. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ Kunqian Catherine Zhu and Man Lavette Chen v Secretary of State for the Home Department, 19 October 2004, retrieved 2024-05-04

- ^ Joined Cases C-297/17, C-318/17, C-319/17 and C-438/17: Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) of 19 March 2019 (requests for a preliminary ruling from the Bundesverwaltungsgericht — Germany) — Bashar Ibrahim (C-297/17), Mahmud Ibrahim and Others (C-318/17), Nisreen Sharqawi, Yazan Fattayrji, Hosam Fattayrji (C-319/17) v Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bundesrepublik Deutschland v Taus Magamadov (C-438/17) (Reference for a preliminary ruling — Area of freedom, security and justice — Common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection — Directive 2013/32/EU — Article 33(2)(a) — Rejection by the authorities of a Member State of an application for asylum as being inadmissible because of the prior granting of subsidiary protection in another Member State — Article 52 — Scope ratione temporis of that directive — Articles 4 and 18 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union — Systemic flaws in the asylum procedure in that other Member State — Systematic rejection of applications for asylum — Substantial risk of suffering inhuman or degrading treatment — Living conditions of those granted subsidiary protection in that other State), 2017, retrieved 2024-05-04

- ^ "Who is entitled to a UK's European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) after Brexit". 2 February 2020.

External links

[edit]European Health Insurance Card

View on GrokipediaEstablishment and Legal Basis

Historical Development

The coordination of social security systems across European Community member states, which included provisions for healthcare access during temporary stays abroad, was established by Council Regulation (EEC) No 1408/71, effective from 1 June 1972. This regulation required the use of multiple paper forms, such as Form E111 for tourists and Form E110 for pensioners, to certify entitlement to medically necessary care, leading to administrative complexities and delays in processing claims.[7] To address these inefficiencies, the European Commission issued a communication on 5 February 2003 proposing a single, standardized European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) to replace the disparate forms while maintaining the existing rights under Regulation 1408/71. The proposal emphasized simplifying verification of insured status for cross-border healthcare providers and reducing paperwork for reimbursement between national authorities. Following Council endorsement, the EHIC was formally introduced on 1 June 2004 as a voluntary instrument, with initial issuance in 13 member states.[7][8] Implementation proceeded gradually, with full recognition across all 25 EU member states plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland achieved by January 2006. The card's design standardized the front side for universal readability while allowing national variations on the reverse for domestic health insurance details. Subsequent modernization occurred with Regulation (EC) No 883/2004, which repealed Regulation 1408/71 and integrated the EHIC into an updated framework applicable from 1 May 2010, enhancing data security and interoperability without altering core entitlements.[9][4]Regulatory Framework

The regulatory framework for the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) is established primarily by Regulation (EC) No 883/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council, adopted on 29 April 2004, which coordinates social security systems across EU member states to protect rights acquired through employment or residence when individuals move within the Union.[10] This regulation applies directly to nationals of member states, stateless persons, and refugees covered by social security legislation, extending to EEA countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway) via the EEA Agreement and to Switzerland through a bilateral accord, with full implementation effective from 1 May 2010 following transitional provisions from the prior Council Regulation (EEC) No 1408/71.[11][1] Central to EHIC functionality are Title III, Chapter 1 provisions on sickness, maternity, and equivalent paternity benefits, notably Article 19(1), which mandates that insured persons temporarily staying in another participating state receive medically necessary benefits in kind from the local institution under conditions identical to those for nationals, provided the stay aligns with the expected duration and medical necessity.[10] The EHIC materializes this right as a portable certificate, obviating prior-authorization forms like the E111 used under the superseded regime, and ensures equality of treatment while limiting coverage to public systems without extending to private care or repatriation costs.[3] Operational procedures, including issuance, reimbursement mechanisms between institutions, and administrative cooperation via the Electronic Exchange of Social Security Information (EESSI) system, are governed by Regulation (EC) No 987/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council, adopted on 16 September 2009, which implements Regulation 883/2004 and standardizes forms for cross-border claims. This includes specifications for electronic processing to reduce administrative burdens, with member states designating liaison bodies for claims settlement within defined timelines (e.g., three months for most reimbursements). The EHIC's uniform design—conforming to ID-1 card dimensions (85.60 mm × 53.98 mm × 0.76 mm) with standardized data fields for identification and entitlement verification—is prescribed by EU implementing decisions, such as those from the Administrative Commission on Social Security, to enable seamless recognition by providers without translation needs.[3] Member states retain responsibility for free issuance to eligible insured persons and their dependents, typically valid for up to five years, but must align with EU specifications to avoid discrepancies in enforcement; non-compliance can trigger infringement proceedings by the European Commission.[1] These rules prioritize public healthcare access during unforeseen needs, reflecting the regulation's causal aim of minimizing barriers to mobility through reciprocal state obligations rather than harmonized entitlements.[11]Scope and Eligibility

Territorial Coverage

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) provides access to medically necessary healthcare on the same terms as residents during temporary stays in the 27 European Union (EU) Member States.[1] These states include Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.[12] Coverage extends to the three European Economic Area (EEA) countries outside the EU: Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, under the EEA Agreement which incorporates EU social security coordination rules.[1] Switzerland participates through a bilateral agreement with the EU, effective since 2002, allowing reciprocal healthcare access equivalent to EHIC provisions.[13] Since the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the EU on February 1, 2020, EHIC validity in the UK is governed by the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement, which maintains reciprocal arrangements for unforeseen medical treatment during temporary visits.[14] Holders from EU/EEA states or Switzerland can use the EHIC for state-provided necessary care in the UK on the same basis as UK residents, though private repatriation or non-essential treatments remain uncovered.[5] The EHIC does not apply to territories outside these jurisdictions, such as overseas departments or other non-European associated territories, nor to non-EEA countries without specific reciprocal agreements.[2] Validity is strictly for temporary stays, not for planned residence or study requiring separate S1 forms or national insurance.[15]Personal Qualifications

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) is issued to individuals who are insured by or covered under a statutory social security scheme in one of the participating countries, comprising the 27 European Union member states, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland.[12] This coverage typically applies to employed persons subject to compulsory insurance, self-employed individuals, and pensioners receiving cash benefits or pensions under the relevant national legislation.[1] Eligibility requires residency in the issuing country and active entitlement to healthcare benefits through the public system, ensuring the card reflects ongoing social security affiliation rather than private or supplemental insurance.[12] Family members of eligible insured persons qualify for their own EHIC if they are entitled to healthcare under the same social security legislation and reside in the competent state.[12] This includes spouses or registered partners, dependent children under the age of 21 (or up to 26 in some systems if in education), and other dependents such as invalided relatives, provided they do not have independent insurance coverage elsewhere.[1] Children covered under a parent's or guardian's policy receive the card without separate contributions, emphasizing dependency on the primary insured's status.[12] Special categories include pensioners drawing pensions from a participating country's social security system, who maintain eligibility post-retirement as long as benefits continue.[12] Full-time students are eligible if insured under their home country's scheme, often through parental coverage or student-specific provisions, but must not be primarily studying abroad without such linkage.[12] Certain countries impose additional national requirements, such as a minimum prior insurance period for eligibility, though these vary and do not alter the core EU-wide criteria of social security coverage.[1] Individuals must apply through their national health authority, with issuance free of charge and valid for the duration of coverage, typically up to five years depending on national policy.[12]Application and Administration

Issuance Procedures

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) is issued free of charge by the statutory health insurance provider in the country of insurance, which operates under national public health schemes across the European Economic Area (EEA) states, Switzerland, and associated territories. Eligible individuals must be covered by or entitled to benefits from a statutory social security scheme of a participating state, including employed or self-employed persons, pensioners, and certain family members such as spouses, dependent children under 21, and other dependents as defined by national rules. Applications require proof of insurance status, such as a national health card number or social security identifier, though specific documentation varies by issuer.[16][1] Issuance procedures are managed nationally without a centralized EU mechanism, allowing applicants to contact their local health authority via online portals, telephone, postal mail, or in-person visits. For instance, in Portugal, applications can be submitted through the Segurança Social Direta online platform or mobile app, with cards mailed within 5 to 7 working days; in Spain, requests are processed via the Social Security electronic office or by calling 901 16 65 65, typically resulting in delivery within similar timelines. In Ireland, applicants provide photo ID, proof of residency, and a Personal Public Service (PPS) number online or by post to the Health Service Executive (HSE), prioritizing digital methods for faster processing. In Poland, eligible individuals can visit any branch or delegation of the National Health Fund (NFZ), submit a completed form (available on-site or pre-downloaded), along with identification (e.g., passport or residence card) and proof of insurance (e.g., ZUS A1 certificate or contribution confirmation), and typically receive the card immediately.[17] Replacements for lost or damaged cards follow identical free procedures, often requiring a declaration of loss.[18][19][20] National variations reflect administrative capacities, with some countries like Lithuania mandating issuance or replacement within 5 working days of application receipt, while others integrate the EHIC digitally into existing national cards without separate requests. Processing times generally range from immediate digital activation to 2-4 weeks for physical cards, and no fees apply under EU coordination rules to ensure accessibility. Applicants outside their home country but insured there may need to coordinate with cross-border contact points designated by each state.[21][1]Role of Third-Party Processors

Third-party processors, often private companies or online services, have emerged to assist individuals in applying for the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC), typically by handling paperwork or expediting requests on behalf of applicants. However, these entities hold no official role in the issuance process, which is exclusively managed by national social security or health insurance institutions across EU/EEA countries and Switzerland, and the card is provided free of charge.[1] Such processors charge fees ranging from €20 to €100 or more for services that duplicate the straightforward official application procedures, leading to unnecessary costs and potential delays.[22] This practice has sparked significant controversy, particularly in countries like the United Kingdom prior to Brexit, where companies advertised "fast-track" EHIC applications, prompting government intervention. In 2010, British authorities targeted firms soliciting payments for free cards, deeming it misleading. By 2016, warnings were issued against scam websites explicitly charging for EHIC processing, with officials emphasizing direct applications via national health services to avoid fraud.[23] Similar issues persisted post-Brexit with the UK's Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC), the EHIC equivalent, where unofficial intermediaries charged up to £30 despite the free official process.[24] EU institutions and national providers consistently advise against using third-party services, as they can expose users to data privacy risks, incomplete applications, or outright scams without providing added value. For instance, the European Commission's guidelines stress applying directly through statutory providers to ensure validity and avoid exploitation.[25] In systems where statutory health insurance is administered by semi-private entities (e.g., competing sickness funds in Germany or the Netherlands), these are regulated public-mandate bodies, not external processors, and still issue EHICs without fees.[26] Overall, third-party involvement remains unofficial and discouraged, with no evidence of systemic benefits outweighing the risks of financial loss or administrative complications.Benefits and Limitations

Covered Services

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) entitles holders to medically necessary healthcare provided by the statutory social security system of the host country during temporary stays, on the same terms and at the same cost as for that country's insured residents. This includes access to state-run hospitals, general practitioners, and pharmacies for treatments deemed essential to restore health or prevent worsening of conditions, without the need for advance payment in most cases. Coverage applies across the 27 EU member states, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom under reciprocal agreements.[1][15] Covered services encompass emergency medical treatment, such as visits to accident and emergency departments for acute injuries or sudden illnesses, as well as ongoing care for pre-existing or chronic conditions that require immediate attention, including renal dialysis, oxygen therapy, and specialized treatments for conditions like asthma or heart disease. Routine maternity care, including prenatal consultations, delivery, and postnatal treatment, is also included if the need arises during the stay, provided it aligns with the host country's public health provisions. For instance, holders can receive prescriptions from public pharmacies at local rates, and hospital inpatient or outpatient services if medically justified.[27][12][28] The scope extends to diagnostic procedures and follow-up care necessary for long-term illnesses, such as echocardiography for chronic cardiac patients, but only within state-provided frameworks; private facilities are generally excluded unless contracted by the public system. In practice, this means free or subsidized access depending on the host nation's policies—for example, free emergency care in public hospitals in countries like Ireland, or reimbursement after upfront payment in others like Greece for certain outpatient services. Variations exist, as coverage mirrors local entitlements: some countries provide free GP visits, while others impose nominal fees waived for EHIC holders equivalent to residents.[6][29][30]Exclusions and Restrictions

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) excludes coverage for treatments provided by private healthcare providers, requiring users to pay full costs upfront with potential partial reimbursement from their home insurer based on applicable national tariffs.[31] It applies solely to public or statutory healthcare systems affiliated with the host country's social security framework.[31] Planned or elective medical treatments fall outside EHIC scope, necessitating prior authorization via separate EU procedures, such as Form S2, to avoid outright refusal of benefits.[15] Coverage restricts to urgent, unplanned care deemed medically necessary and postponable only at risk to health or life during temporary stays.[15] If travel appears motivated primarily by seeking treatment, providers may deny EHIC use, treating it as planned care.[6] Repatriation, rescue operations, and transport back to the home country after illness or accident receive no coverage, as illustrated by cases like uncovered ski rescues in host nations.[15] The EHIC does not substitute for comprehensive travel insurance, omitting extras such as accommodation during recovery, lost property, or non-medical evacuation costs.[1] Benefits align strictly with those afforded to host country residents, imposing user fees for unsubsidized elements like prescriptions, dental work beyond emergencies, or hospital single rooms, with reimbursements capped at host or home country rates—whichever is lower.[6] Non-EU nationals face additional restrictions, unable to use the EHIC in Denmark, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, or Switzerland absent refugee status in an EU state or linkage as family to an EU citizen.[15] Without the physical card, upfront payments at potentially higher private rates apply, with home reimbursement limited to domestic equivalents.[6]Implementation Across States

EU/EEA and Associated Countries

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) entitles holders insured under statutory social security schemes in one member state to receive medically necessary, state-provided healthcare during temporary stays in any of the 27 EU countries, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, or Switzerland, on the same terms and at the same cost as residents of the visited country.[1] This coverage applies to unforeseen illnesses or accidents, excluding planned treatments unless authorized separately via form S2.[2] The scheme operates under Regulation (EC) No 883/2004, which harmonizes social security coordination across these jurisdictions.[1] Issuance of the EHIC is managed by national health insurance institutions designated by each participating state, provided free to eligible residents including citizens, family members, pensioners, and certain posted workers.[2] Validity durations differ: for instance, five years in Denmark, while others issue shorter terms renewable upon expiry.[32] EEA countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway) implement the EHIC through incorporation into the EEA Agreement, aligning with EU acquis to ensure seamless reciprocity.[1] Switzerland's participation stems from bilateral agreements with the EU, effective since 2014, covering similar emergency and necessary care provisions without altering domestic eligibility rules.[1] While the core functionality is standardized, administrative practices vary; cards may be plastic with chips in countries like Germany or simpler photo IDs elsewhere, but all must feature the EU flag, "European Health Insurance Card" inscription, and holder details for validation at point of service.[1] Providers in host countries bill the home institution retrospectively via electronic claims systems, minimizing patient out-of-pocket costs beyond local co-payments.[33] Non-compliance with card presentation can lead to full private payment obligations, underscoring the need for prior application before travel.[2]United Kingdom Post-Brexit Adjustments

Following the end of the Brexit transition period on December 31, 2020, United Kingdom residents ceased to be eligible for new European Health Insurance Cards (EHICs), as the UK withdrew from the European Economic Area (EEA) social security coordination framework that underpins the scheme. Existing EHICs issued to UK residents prior to this date remained valid for use in EU/EEA countries and Switzerland until their printed expiry dates, after which UK residents were required to apply for the replacement UK Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC). The GHIC, launched by the UK government in 2019 but activated for post-Brexit use from January 1, 2021, entitles holders to medically necessary state-provided healthcare during temporary stays in participating countries on the same terms and at the same cost as residents of those countries. This coverage stems from reciprocal arrangements under the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) for EU/EEA states and separate bilateral agreements for select non-EU nations, such as Australia and New Zealand, but excludes private healthcare, repatriation, or non-essential treatments.[27][34] The GHIC application process is managed by the NHS Business Services Authority and is free for eligible UK residents, including British citizens and those with settled or pre-settled status under the EU Settlement Scheme; applications can be submitted online up to nine months before an existing card's expiry, with new cards typically valid for five years. Unlike the EHIC, the GHIC extends potential coverage beyond Europe to countries with UK reciprocal healthcare pacts, though its acceptance in EEA states like Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway requires confirmation via bilateral terms, as these were not uniformly transitioned under the TCA. UK authorities emphasize that neither EHIC nor GHIC substitutes for comprehensive travel insurance, which must cover potential costs exceeding state provisions, such as emergency evacuations estimated to average £10,000-£20,000 per case based on historical data from repatriation services. Failure to obtain such insurance has led to documented cases of substantial out-of-pocket expenses for UK travelers post-2021.[27][35] For visitors from EU/EEA countries and Switzerland entering the UK, EHICs issued by their home states continue to provide access to medically necessary NHS treatment on the same basis as UK residents, without the need for private insurance to cover state care, under the TCA's reciprocal provisions effective from January 1, 2021. Existing EHICs remain valid until their expiry dates, with no issuance of new EHICs by UK authorities for non-UK residents; Swiss nationals gained explicit EHIC recognition in the UK from November 1, 2021, following a separate bilateral deal. This arrangement applies only to temporary visitors and excludes routine or elective care, with EU visitors responsible for any costs beyond state entitlements, such as ambulance fees averaging £400-£500 or dental treatments outside emergencies. UK border and healthcare providers enforce presentation of valid EHICs alongside passports, with non-compliance potentially resulting in full payment demands, as evidenced by NHS rejection logs post-Brexit.[36][37] These adjustments reflect the UK's shift to independent reciprocal healthcare diplomacy, prioritizing fiscal containment by limiting entitlements to state-funded necessities and encouraging private insurance uptake, which has risen approximately 15-20% among outbound UK travelers since 2021 per industry reports. No automatic extension of EHIC/GHIC benefits applies to permanent UK expatriates, who must secure local health coverage in their country of residence. Ongoing monitoring by the Department of Health and Social Care ensures compliance with TCA dispute mechanisms, though isolated reports of inconsistent EHIC reimbursements in the UK highlight administrative variances across NHS trusts.[36]Practical Usage and Challenges

Activation and Reimbursement Processes

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) requires no separate activation beyond its issuance by the holder's national health insurance institution, rendering it immediately valid for use during temporary stays in participating countries.[1] Holders must present the physical card or its digital equivalent—available via apps or insurer portals in some states—at public or state-contracted healthcare providers to receive medically necessary treatment on equivalent terms to insured residents, including any applicable co-payments or fees.[31] Failure to present the EHIC may result in full upfront payment, necessitating subsequent reimbursement claims, as the card facilitates direct settlement between institutions in many cases but does not guarantee exemption from local patient contributions.[6] Reimbursement processes vary by the treating country and insurer but generally prioritize direct access over refunds; where payment occurs, claimants submit documentation to their home institution post-treatment.[6] Required materials include original invoices detailing services and costs, medical certificates confirming necessity, proof of payment, and the EHIC number; digital submissions are increasingly accepted via insurer portals, with processing times ranging from weeks to months depending on the state.[38] Reimbursements are capped at the home country's tariff rates for equivalent care, potentially leaving holders liable for differences if foreign costs exceed domestic equivalents—e.g., higher specialist fees in some EEA states.[39] On-site claims are possible in select countries through local health funds, where the EHIC enables provisional refunds before inter-state billing resolves balances, though this depends on bilateral agreements and provider cooperation.[14] In practice, direct institutional reimbursement—where the foreign provider bills the home insurer—occurs in over 80% of EHIC cases across the EU/EEA, reducing patient outlays, but gaps persist in non-public settings or for repatriation costs, which remain excluded.[1] Delays in claims, averaging 30-60 days, have prompted digital initiatives like the European Health Insurance Card Cooperation Committee to standardize electronic processing by 2026, aiming to minimize administrative burdens.[14] Holders denied coverage due to card expiration or ineligibility must pursue private claims, often yielding lower recovery rates without EHIC validation.[40]Access Barriers and Rejection Cases

Access to healthcare via the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) can be impeded by several barriers, including invalid or expired cards, treatment sought in private facilities outside public systems, and administrative or procedural misunderstandings by providers. Holders must present a valid EHIC to receive care on the same terms as locals in public facilities across participating states; without it, patients are typically required to pay upfront and seek reimbursement from their home insurer, which delays care and incurs out-of-pocket costs.[6] [41] The card's validity is limited—typically five years for most issuers—and failure to renew or carry it results in rejection, as providers verify entitlement at the point of service.[16] Rejection cases often stem from provider-side issues, such as insufficient training on EHIC protocols or preferences for immediate payment to avoid reimbursement delays from cross-border authorities. In reporting member states, common refusal rationales include providers' lack of procedural knowledge, perceived administrative burdens in processing claims, and skepticism over timely reimbursements from foreign institutions.[25] Private clinics and hospitals, which operate outside state-funded systems, routinely decline the EHIC, as it entitles holders only to public-sector equivalents; upfront payment is standard, with no guarantee of acceptance even if the facility contracts with public payers.[42] Notable enforcement challenges arose in Spain, where public hospitals in regions like Andalusia and the Balearic Islands rejected EHIC claims from non-resident EU citizens in 2012–2013, directing patients—often British tourists—to private insurance or self-payment despite eligibility for urgent care.[43] The European Commission documented multiple instances of such denials, attributing them to local fiscal pressures and inadequate implementation, leading to a formal infringement procedure and reasoned opinion against Spain in May 2013.[44] Similar procedural gaps persist in countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, and Iceland, where provider unfamiliarity with EHIC verification exacerbates access denials for unplanned treatments.[45] These cases highlight systemic variances in national adherence, where economic incentives or resource constraints can override EHIC entitlements, prompting patients to rely on supplementary travel insurance for recourse.[46]Criticisms and Economic Realities

Fraud Vulnerabilities and Abuse Patterns

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) exhibits vulnerabilities to fraud stemming from its design as a portable document reliant on mutual trust among Member States' institutions, without mandatory real-time electronic verification or identity checks at the point of service. Healthcare providers often accept the EHIC presumptively for urgent care, enabling retrospective claims that are difficult to audit, particularly when patients present valid-looking cards issued online with minimal scrutiny. Counterfeit or expired cards can be used undetected, as non-electronically readable formats persist in some states, and coordination rules lack uniform enforcement for validating holder eligibility, such as temporary stay status.[25][47] Abuse patterns frequently involve uninsured individuals or non-residents misrepresenting themselves as temporarily present to access state-funded care, leading to ineligible reimbursements. In Bulgaria, 3.2% of cross-border reimbursements in 2015 were deemed fraudulent due to ineligible EHIC holders, totaling €750,000. Similar issues arose in Lithuania (2.3% of claims), Estonia (1.8%), Czech Republic (0.9%), and Austria (0.7%), with specific cases including 791 invalid uses in Austria amounting to €189,868 and 193 in Estonia costing €175,297.[25][47] Fraudulent practices also include the use of counterfeit EHICs, as reported in Spain and Poland, where cards were forged or lent to unauthorized users, and the pursuit of planned rather than unforeseen treatments, such as in Estonia where EHICs covered non-urgent procedures. Overseas visitors sometimes exploit reciprocal agreements by failing to notify permanent relocation, allowing continued claims under outdated eligibility, a pattern contributing to an estimated £467,750 in vulnerabilities from £92.2 million in UK reciprocal expenditures in 2022-2023. Incomplete or retrospective form submissions, like E125 certificates lacking treatment details, further enable duplicate or invalid claims across borders.[25][47][48] Efforts to mitigate these rely on Administrative Commission Decision S1 for inter-institutional cooperation, including data sharing to detect misuse, though implementation varies, with some states like the UK prosecuting fraudulent issuance sites and others advocating ID-linked electronic cards. Despite this, underreporting persists, as seven Member States documented no EHIC-related fraud in surveys, potentially reflecting gaps in monitoring rather than absence.[25][47][49]Cross-Border Cost Imbalances

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) facilitates cross-border healthcare under Regulation (EC) No 883/2004, where the competent institution in the patient's home member state reimburses the institution of stay for the actual costs incurred, often at the treating country's higher tariffs.[50] This mechanism exposes disparities due to varying healthcare costs and patient mobility patterns across EU/EEA states, with wealthier northern and western countries frequently incurring net outflows while southern tourist destinations experience inflows.[51] In 2023, EU/EEA institutions processed approximately 2.3 million outgoing reimbursement claims totaling €1.3 billion from home states, while treating states received €1.1 billion for 2.2 million claims, reflecting a slight overall surplus for treating institutions but significant bilateral asymmetries.[50] Germany, as a net payer, disbursed €292 million for its citizens' care abroad against €198.7 million received for foreigners treated domestically, yielding a €93.3 million net outflow.[50] Similarly, the United Kingdom paid €277 million outgoing, including €181 million to France alone for treatments received by UK nationals there.[50] These imbalances stem from directional flows: patients from high-mobility states like Germany and the UK seek care in popular destinations such as France (€158.5 million received by Spain across flows, but France dominant in inflows) and Austria (€76 million from Germany to Austria), where local tariffs exceed those in origin countries.[50] Newer EU member states (EU-13) face disproportionately higher relative burdens, with cross-border expenditures comprising up to 0.69% of their total health budgets compared to 0.05% in older members (EU-14), exacerbating fiscal strain in lower-expenditure systems.[52] Overall, such activity remains marginal at under 0.02% of aggregate EU health spending, yet persistent net payer status for states like Germany highlights uncompensated transfers effectively subsidizing care in net receiver countries.[51]Taxpayer Funding and Efficiency Concerns

The European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) is financed through the national health systems of EU/EEA member states, which are predominantly taxpayer-funded via general taxation, social insurance contributions, or both, imposing direct costs on residents of the issuing country for treatments received abroad. Competent member states reimburse or cover expenses incurred by their citizens in other states, with total EHIC-related cross-border expenditures reaching approximately €1.1 billion from the treatment perspective and €1.3 billion from the competent state perspective in 2023.[53] These outflows represent an average budgetary impact of 0.18% of total national healthcare spending, though this varies significantly by country.[53] Disparities in financial burdens are evident, particularly between newer EU member states (EU-13, often Eastern European) and older ones (EU-14), with the former facing a higher relative expenditure of 0.31% of healthcare budgets compared to 0.06% for the latter. Eastern European states experience outflows of €517 per €1 million of total health expenditure for EHIC patients seeking care in Western Europe, where treatment costs average €451 per patient—substantially higher than the €300 average in Eastern systems—exacerbating resource drains on less affluent budgets. In absolute terms, Western outflows dominate (1.5 million patients in 2016), but the relative strain on Eastern systems undermines efficiency by diverting funds from domestic care without proportional reciprocal inflows. For instance, in 2016, Eastern outflows totaled €68 million for 200,000 patients, amplifying per-capita pressures in states with lower overall health spending.[53][54] Efficiency challenges compound taxpayer costs through administrative inefficiencies and rejection rates. In 2023, rejection rates for EHIC claims averaged 5.9% by foreign institutions and 16.6% by domestic ones, with extremes like 48.9% in Hungary, leading to delayed reimbursements, error corrections, and additional processing expenses that strain public finances. Cases of fraud or errors, such as €672,481 in France, further erode value, while ambiguities in defining "necessary" care—e.g., disputes over pregnancy coverage—result in inconsistent application and potential over-treatment abroad at higher costs. National examples highlight per-case escalation: Ireland's EHIC expenditures rose to €4.24 million in 2017 for 18,744 episodes (serving 12,621 persons), up from €3.91 million in 2016 despite 31% fewer episodes and 29% fewer users, signaling rising unit costs amid static or declining volume.[53][55]| Member State | EHIC Claims Paid (€M, 2023) | Key Efficiency Note |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | 292 | High inflows/outflows balance strained admin.[53] |

| France | 253 | €672k fraud/errors reported.[53] |

| Spain | 158 (received) | Rising inflows increase domestic pressure.[53] |