Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| see also euro in various languages | |

|---|---|

Euro banknotes (obverse) | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | EUR (numeric: 978) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Unit | euro |

| Plural | Varies, see language and the euro |

| Symbol | € |

| Nickname | The single currency[a] |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | euro cent (Name varies by language) |

| Plural | |

| euro cent | (Varies by language) |

| Symbol | |

| euro cent | c |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | €5, €10, €20, €50, €100[2] |

| Rarely used | €200, €500[2] |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | 1c, 2c, 5c, 10c, 20c, 50c, €1, €2 |

| Rarely used | 1c, 2c (Belgium, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Slovakia[3][4][5][6]) |

| Demographics | |

| Date of introduction | 1 January 1999 |

| Replaced | European Currency Unit |

| User(s) | primary: § members of Eurozone (20), also: § other users |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | European Central Bank |

| Website | www |

| Printer | see § Banknote printing |

| Mint | List of mints |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 2.2% (September 2025)[7] |

| Source | ec.europa.eu |

| Method | HICP |

| Pegged by | see § Pegged currencies |

| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

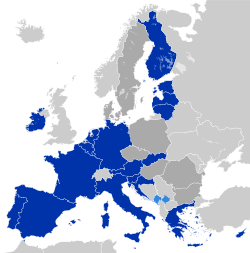

The euro (symbol: €; currency code: EUR) is the official currency of 20 of the 27 member states of the European Union. This group of states is officially known as the euro area or, more commonly, the eurozone. The euro is divided into 100 euro cents.[8][9]

The currency is also used officially by the institutions of the European Union, by four European microstates that are not EU members,[9] and the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, as well as unilaterally by Montenegro and Kosovo. Outside Europe, a number of special territories of EU members also use the euro as their currency.

The euro is used by 350 million people in Europe, and over 200 million people worldwide use currencies pegged to the euro.[10] It is the second-largest reserve currency as well as the second-most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar.[11][12][13][14][15] As of December 2019,[update] with more than €1.3 trillion in circulation, the euro has one of the highest combined values of banknotes and coins in circulation in the world.[16][17]

The name euro was officially adopted on 16 December 1995 in Madrid.[18] The euro was introduced to world financial markets as an accounting currency on 1 January 1999, replacing the former European Currency Unit (ECU) at a ratio of 1:1 (US$1.1743 at the time). Physical euro coins and banknotes entered into circulation on 1 January 2002, making it the day-to-day operating currency of its original members, and by March 2002 it had completely replaced the former currencies.[19]

Between December 1999 and December 2002, the euro traded below parity with the US dollar, but it has since traded near or above parity with the US dollar. On 13 July 2022, the two currencies briefly hit parity for the first time in nearly two decades, due in part to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[20] In the ten years ending 30 September 2025, the rate has averaged at about $1.00:€0.92.[21]

Characteristics

[edit]Administration

[edit]

The euro is managed and administered by the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem, composed of the central banks of the eurozone countries.[22] As an independent central bank, the ECB has sole authority to set monetary policy.[23] The Eurosystem participates in the printing, minting and distribution of euro banknotes and coins in all member states,[24] and the operation of the eurozone payment systems.[25]

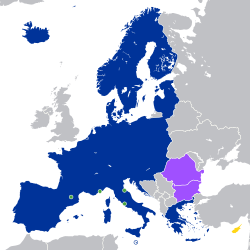

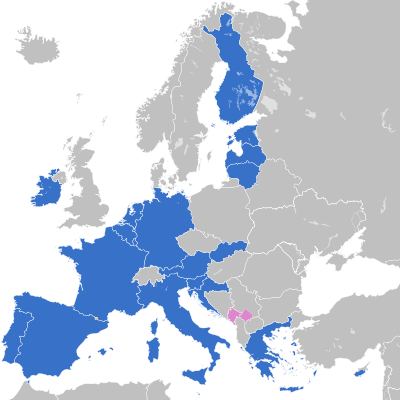

Through their ratification of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty (or subsequent treaties of accession), most EU member states committed to adopt the euro upon meeting certain monetary and budgetary convergence criteria, although not all participating states have done so. Denmark has negotiated exemptions,[26] while Sweden (which joined the EU in 1995, after the Maastricht Treaty was signed) turned down the euro in a 2003 non-binding referendum, and has circumvented its commitment to adopt the euro by not meeting the monetary and budgetary requirements. All nations that have joined the EU since 1993 have pledged to adopt the euro in due course. The Maastricht Treaty was amended by the 2001 Treaty of Nice, which closed the gaps and loopholes in the Maastricht and Rome Treaties.[27]

Countries that use the euro

[edit]The euro is the official currency of 43 countries and territories:

Eurozone members

[edit]The 20 participating members are:

Special Autonomous Territories:

Other users

[edit]Microstates with a monetary agreement:

Unilateral adopters:

EU members not using the euro

[edit]

Acceding to the eurozone

[edit] Bulgaria: Bulgaria has been approved to replace the Bulgarian lev with the euro on 1 January 2026.[35]

Bulgaria: Bulgaria has been approved to replace the Bulgarian lev with the euro on 1 January 2026.[35]

Committed to adopt the euro

[edit]The following five EU member states, representing almost 90 million people, committed themselves in their respective Treaty of Accession to adopt the euro. However they do not have a deadline to do so and can delay the process by deliberately not complying with the convergence criteria (such as by not meeting the convergence criteria to join ERM II).

Opt-outs

[edit]The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 included protocols on Denmark and the United Kingdom, giving them opt-outs with the right to decide if and when they would adopt the euro.[36]

Denmark: The government of Denmark negotiated an opt-out to retain usage of the Danish krone, but the currency is pegged to the euro via the ERM II, the European Union's exchange rate mechanism.

Denmark: The government of Denmark negotiated an opt-out to retain usage of the Danish krone, but the currency is pegged to the euro via the ERM II, the European Union's exchange rate mechanism. United Kingdom: Prior to its withdrawal from the European Union in 2020, the United Kingdom negotiated an opt-out to retain usage of the pound sterling.

United Kingdom: Prior to its withdrawal from the European Union in 2020, the United Kingdom negotiated an opt-out to retain usage of the pound sterling.

Coins and banknotes

[edit]Coins

[edit]

The euro is divided into 100 cents (also referred to as euro cents, especially when distinguishing them from other currencies, and referred to as such on the common side of all cent coins). In Community legislative acts the plural forms of euro and cent are spelled without the s, notwithstanding normal English usage.[37][38] Otherwise, normal English plurals are used,[39] with many local variations such as centime in France.

All circulating coins have a common side showing the denomination or value and a map in the background. Due to the linguistic plurality in the European Union, the Latin alphabet version of euro is used (as opposed to the less common Greek or Cyrillic) and Arabic numerals (other text is used on national sides in national languages, but other text on the common side is avoided). For the denominations except the 1-, 2- and 5-cent coins, the map only showed the 15 member states of the union as of 2002. Beginning in 2007 or 2008 (depending on the country), the old map was replaced by a map of Europe also showing countries outside the EU.[40] The 1-, 2- and 5-cent coins, however, keep their old design, showing a geographical map of Europe with the EU member states as of 2002, raised somewhat above the rest of the map. All common sides were designed by Luc Luycx. The coins also have a national side showing an image specifically chosen by the country that issued the coin. Euro coins from any member state may be freely used in any nation that has adopted the euro.

The coins are issued in denominations of €2, €1, 50c, 20c, 10c, 5c, 2c, and 1c. To avoid the use of the two smallest coins, some cash transactions are rounded to the nearest five cents in the Netherlands and Ireland[41][42] (by voluntary agreement) and in Finland and Italy (by law).[43] This practice is discouraged by the commission, as is the practice of certain shops of refusing to accept high-value euro notes.[44]

Commemorative coins with €2 face value have been issued with changes to the design of the national side of the coin. These include both commonly issued coins, such as the €2 commemorative coin for the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Rome, and nationally issued coins, such as the coin to commemorate the 2004 Summer Olympics issued by Greece. These coins are legal tender throughout the eurozone. Collector coins with various other denominations have been issued as well, but these are not intended for general circulation, and they are legal tender only in the member state that issued them.[45]

|

|

|

Vatican euro coins with images of Pope Francis and Pope Benedict XVI

Coin minting

[edit]A number of institutions are authorised to mint euro coins:

- Bayerisches Hauptmünzamt (Mint mark: D)

- Currency Centre

- Real Casa de la Moneda

- Hamburgische Münze (J)

- Hrvatska kovnica novca

- Banknote and Securities Printing Foundation

- Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda

- Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato

- Koninklijke Munt van België/Monnaie Royale de Belgique

- Koninklijke Nederlandse Munt

- Lietuvos monetų kalykla

- Mincovňa Kremnica

- Monnaie de Paris

- Münze Österreich

- Suomen Rahapaja/Myntverket i Finland

- Staatliche Münze Berlin (A)

- Staatliche Münzen Baden-Württemberg (F): Stuttgart, (G): Karlsruhe

Banknotes

[edit]

The design for the euro banknotes has common designs on both sides. The design was created by the Austrian designer Robert Kalina.[46] Notes are issued in €500, €200, €100, €50, €20, €10, and €5. Each banknote has its own colour and is dedicated to an artistic period of European architecture. The front of the note features windows or gateways while the back has bridges, symbolising links between states in the union and with the future. While the designs are supposed to be devoid of any identifiable characteristics, the initial designs by Robert Kalina were of specific bridges, including the Rialto and the Pont de Neuilly, and were subsequently rendered more generic; the final designs still bear very close similarities to their specific prototypes; thus they are not truly generic. The monuments looked similar enough to different national monuments to please everyone.[47]

The Europa series, or second series, consists of six denominations and no longer includes the €500 with issuance discontinued as of 27 April 2019.[48] However, both the first and the second series of euro banknotes, including the €500, remain legal tender throughout the euro area.[48]

In December 2021, the ECB announced its plans to redesign euro banknotes by 2024. A theme advisory group, made up of one member from each euro area country, was selected to submit theme proposals to the ECB. The proposals will be voted on by the public; a design competition will also be held.[49]

Issuing modalities for banknotes

[edit]Since 1 January 2002, the national central banks (NCBs) and the ECB have issued euro banknotes on a joint basis.[50] Eurosystem NCBs are required to accept euro banknotes put into circulation by other Eurosystem members and these banknotes are not repatriated. The ECB issues 8% of the total value of banknotes issued by the Eurosystem.[50] In practice, the ECB's banknotes are put into circulation by the NCBs, thereby incurring matching liabilities vis-à-vis the ECB. These liabilities carry interest at the main refinancing rate of the ECB. The other 92% of euro banknotes are issued by the NCBs in proportion to their respective shares of the ECB capital key,[50] calculated using national share of European Union (EU) population and national share of EU GDP, equally weighted.[51]

| Image | Value | Year | Dimensions (millimetres) |

Main colour | Design | Printer code position | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | Reverse | Architecture | Century | ||||||||

| €5 | 2013 | 120 × 62 mm | Grey[52] | Classical | 8th BC–4th AD | Top right | |||||

| €10 | 2014 | 127 × 67 mm | Red[53] | Romanesque | 11–12th | ||||||

|

|

€20 | 2015 | 133 × 72 mm | Blue[54] | Gothic | 13–14th | ||||

|

|

€50 | 2017 | 140 × 77 mm | Orange[55] | Renaissance | 15–16th | ||||

|

|

€100 | 2019 | 147 × 77 mm | Green[56] | Baroque & Rococo | 17–18th | ||||

|

|

€200 | 153 × 77 mm | Yellow-brown[57] | Art Nouveau | 19th | |||||

| These images are to scale at 0.7 pixel per millimetre (18 pixel per inch). For table standards, see the banknote specification table. | |||||||||||

Banknote printing

[edit]Member states are authorised to print or to commission bank note printing. As of November 2022[update], these are the printers:

Payments clearing, electronic funds transfer

[edit]Capital within the EU may be transferred in any amount from one state to another. All intra-Union transfers in euro are treated as domestic transactions and bear the corresponding domestic transfer costs.[58] This includes all member states of the EU, even those outside the eurozone providing the transactions are carried out in euro.[59] Credit/debit card charging and ATM withdrawals within the eurozone are also treated as domestic transactions; however paper-based payment orders, like cheques, have not been standardised so these are still domestic-based. The ECB has also set up a clearing system, T2 since March 2023, for large euro transactions.[60]

History

[edit]Introduction

[edit]| Currency | Code | Rate[61] | Fixed on | Yielded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austrian schilling | ATS | 13.7603 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Belgian franc | BEF | 40.3399 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Dutch guilder | NLG | 2.20371 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Finnish markka | FIM | 5.94573 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| French franc | FRF | 6.55957 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| German mark | DEM | 1.95583 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Irish pound | IEP | 0.787564 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Italian lira | ITL | 1,936.27 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Luxembourg franc | LUF | 40.3399 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Portuguese escudo | PTE | 200.482 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Spanish peseta | ESP | 166.386 | 31 December 1998 | 1 January 1999 |

| Greek drachma | GRD | 340.750 | 19 June 2000 | 1 January 2001 |

| Slovenian tolar | SIT | 239.640 | 11 July 2006 | 1 January 2007 |

| Cypriot pound | CYP | 0.585274 | 10 July 2007 | 1 January 2008 |

| Maltese lira | MTL | 0.429300 | 10 July 2007 | 1 January 2008 |

| Slovak koruna | SKK | 30.1260 | 8 July 2008 | 1 January 2009 |

| Estonian kroon | EEK | 15.6466 | 13 July 2010 | 1 January 2011 |

| Latvian lats | LVL | 0.702804 | 9 July 2013 | 1 January 2014 |

| Lithuanian litas | LTL | 3.45280 | 23 July 2014 | 1 January 2015 |

| Croatian kuna | HRK | 7.53450 | 12 July 2022 | 1 January 2023 |

| Bulgarian lev | BGN | 1.95583 | 8 July 2025 | 1 January 2026 |

The euro was established by the provisions in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty.[62][63] To participate in the currency, member states are meant to meet strict criteria, such as a budget deficit of less than 3% of their GDP, a debt ratio of less than 60% of GDP (both of which were ultimately widely flouted after introduction), low inflation, and interest rates close to the EU average.[64][65] In the Maastricht Treaty, the United Kingdom and Denmark were granted exemptions per their request from moving to the stage of monetary union which resulted in the introduction of the euro (see also United Kingdom and the euro).[66][67]

The name "euro" was officially adopted in Madrid on 16 December 1995.[18] Belgian Esperantist Germain Pirlot, a former teacher of French and history, is credited with naming the new currency by sending a letter to then President of the European Commission, Jacques Santer, suggesting the name "euro" on 4 August 1995.[68]

Due to differences in national conventions for rounding and significant digits, all conversion between the national currencies had to be carried out using the process of triangulation via the euro.[69] The definitive values of one euro in terms of the exchange rates at which the currency entered the euro are shown in the table.

The rates were determined by the Council of the European Union,[f] based on a recommendation from the European Commission based on the market rates on 31 December 1998. They were set so that one European Currency Unit (ECU) would equal one euro. The European Currency Unit was an accounting unit used by the EU, based on the currencies of the member states; it was not a currency in its own right. They could not be set earlier, because the ECU depended on the closing exchange rate of the non-euro currencies (principally pound sterling) that day.

The procedure used to fix the conversion rate between the Greek drachma and the euro was different since the euro by then was already two years old. While the conversion rates for the initial eleven currencies were determined only hours before the euro was introduced, the conversion rate for the Greek drachma was fixed several months beforehand.[g]

The currency was introduced in non-physical form (traveller's cheques, electronic transfers, banking, etc.) at midnight on 1 January 1999, when the national currencies of participating countries (the eurozone) ceased to exist independently. Their exchange rates were locked at fixed rates against each other. The euro thus became the successor to the European Currency Unit (ECU). The notes and coins for the old currencies, however, continued to be used as legal tender until new euro notes and coins were introduced on 1 January 2002.

The changeover period during which the former currencies' notes and coins were exchanged for those of the euro lasted about two months, until 28 February 2002. The official date on which the national currencies ceased to be legal tender varied from member state to member state. The earliest date was in Germany, where the mark officially ceased to be legal tender on 31 December 2001, though the exchange period lasted for two months more. Even after the old currencies ceased to be legal tender, they continued to be accepted by national central banks for periods ranging from several years to indefinitely (the latter for Austria, Germany, Ireland, Estonia and Latvia in banknotes and coins, and for Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Slovakia in banknotes only). The earliest coins to become non-convertible were the Portuguese escudos, which ceased to have monetary value after 31 December 2002, although banknotes remained exchangeable until 2022.

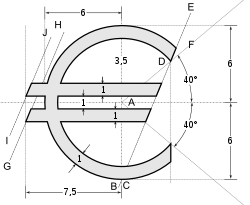

Currency sign

[edit]

A special euro currency sign (€) was designed after a public survey had narrowed ten of the original thirty proposals down to two. The President of the European Commission at the time (Jacques Santer) and the European Commissioner with responsibility for the euro (Yves-Thibault de Silguy) then chose the winning design.[70]

Regarding the symbol, the European Commission stated on behalf of the European Union:

The symbol € is based on the Greek letter epsilon (Є), with the first letter in the word "Europe" and with 2 parallel lines signifying stability.

The European Commission also specified a euro logo with exact proportions.[71] Placement of the currency sign relative to the numeric amount varies from state to state, but for texts in English published by EU institutions, the symbol (or the ISO-standard "EUR") should precede the amount.[72]

Eurozone crisis

[edit]

Following the 2008 financial crisis, fears of a sovereign default developed in 2009 among investors concerning some European states, with the situation becoming particularly tense in early 2010.[73][74] Greece was most acutely affected, but fellow Eurozone members Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain were also significantly affected.[75][76] All these countries used EU funds except Italy, which is a major donor to the EFSF.[77] To be included in the eurozone, countries had to fulfil certain convergence criteria, but the meaningfulness of such criteria was diminished by the fact it was not enforced with the same level of strictness among countries.[78]

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2011, "[I]f the [euro area] is treated as a single entity, its [economic and fiscal] position looks no worse and in some respects, rather better than that of the US or the UK" and the budget deficit for the euro area as a whole is much lower and the euro area's government debt/GDP ratio of 86% in 2010 was about the same level as that of the United States. "Moreover", they write, "private-sector indebtedness across the euro area as a whole is markedly lower than in the highly leveraged Anglo-Saxon economies". The authors conclude that the crisis "is as much political as economic" and the result of the fact that the euro area lacks the support of "institutional paraphernalia (and mutual bonds of solidarity) of a state".[79]

The crisis continued with S&P downgrading the credit rating of nine euro-area countries, including France, then downgrading the entire European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) fund.[80]

A historical parallel – to 1931 when Germany was burdened with debt, unemployment and austerity while France and the United States were relatively strong creditors – gained attention in summer 2012[81] even as Germany received a debt-rating warning of its own.[82][83]

Direct and indirect usage

[edit]Agreed direct usage with minting rights

[edit]The euro is the sole currency of 20 EU member states: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. These countries constitute the "eurozone", some 347 million people in total as of 2023[update].[84] According to bilateral agreements with the EU, the euro has also been designated as the sole and official currency in a further four European microstates awarded minting rights (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City). All other EU member states (except Denmark, which has an opt-out), and any potential future members, are obliged to adopt the euro when economic conditions permit.

Agreed direct usage without minting rights

[edit]The euro is also the sole currency in three overseas territories of France that are not themselves part of the EU, namely Saint Barthélemy, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and the French Southern and Antarctic Lands, as well as in the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia.[85]

Unilateral direct usage

[edit]The euro has been adopted unilaterally as the sole currency of Montenegro and Kosovo. It has also been used as a foreign trading currency in Cuba since 1998,[86] Syria since 2006,[87] and Venezuela since 2018.[88] In 2009, Zimbabwe abandoned its local currency and introduced major global convertible currencies instead, including the euro and the United States dollar. The direct usage of the euro outside of the official framework of the EU affects nearly 3 million people.[89]

Currencies pegged to the euro

[edit]

Outside the eurozone, two EU member states have currencies that are pegged to the euro, which is a precondition to joining the eurozone. The Danish krone and Bulgarian lev are pegged through to their participation in the ERM II.

On the other hand, the currencies of countries and territories that were pegged to the European currencies that disappeared with the creation of the euro were now pegged to it. Currently, they are as follows:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: The Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark was pegged to the Deutsche mark. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 1.95583 convertible marks = 1 euro.

- Cape Verde: The Cape Verdean escudo was pegged to the Portuguese escudo. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 110.625 Cape Verdean escudos = 1 euro.

- Comoros: The Comorian franc was pegged to the French franc. Currently, it has a fixed exchange rate of 491.96775 Comorian francs = 1 euro.

- Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and the Republic of the Congo): the Central African CFA franc was pegged to the French franc. It currently has a fixed exchange rate of 655.957 Central African CFA francs = 1 euro.

- North Macedonia: The Macedonian denar was pegged to the Deutsche mark. It is currently pegged to the euro. Its exchange rate remains stable at around 61 Macedonian denars to 1 euro.

- West African Economic and Monetary Union (Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo): The West African CFA franc was pegged to the French franc. It currently has a fixed exchange rate of 655.957 West African CFA francs = 1 euro.

- The French overseas collectivities of French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna as well as the special collectivity of New Caledonia: the CFP franc was pegged to the French franc. It currently has a fixed exchange rate of 1000 CFP francs = 8.38 euros, which makes 119.331742 CFP francs ≈ 1 euro.

Furthermore, the currency of São Tomé and Príncipe (the São Tomé and Príncipe dobra) is pegged to the euro following an agreement signed with Portugal in 2009 and which came into effect on 1 January 2010.[90] It has a fixed exchange rate of 24.5 São Tomé and Príncipe dobras = 1 euro.

Of the currencies mentioned, the Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark maintains a fixed exchange rate through the currency board system; the Central African CFA franc, the West African CFA franc, the CFP franc, the Cape Verdean escudo, the Comorian franc, and the São Tomé and Príncipe dobra maintain a conventional fixed exchange rate; and the Macedonian denar uses a stabilized arrangement. Additionally, the currency of Morocco, the Moroccan dirham, is pegged to the euro through a basket of currencies. Other countries that, as of December 2023, have exchange rate regimes linked to the euro are Romania, Serbia, Singapore, Botswana, Tunisia, Samoa, Fiji, Libya, Kuwait, Syria, China and Vanuatu.[91][92][93][94]

Pegging a country's currency to a major currency is regarded as a safety measure, especially for currencies of areas with weak economies, as the euro is seen as a stable currency, prevents runaway inflation, and encourages foreign investment due to its stability.

In total, as of 2013[update], 182 million people in Africa use a currency pegged to the euro, 27 million people outside the eurozone in Europe, and another 545,000 people on Pacific islands.[84]

Since 2005, stamps issued by the Sovereign Military Order of Malta have been denominated in euros, although the Order's official currency remains the Maltese scudo.[95] The Maltese scudo itself is pegged to the euro and is only recognised as legal tender within the Order.

Countries and territories that have their currencies pegged to the euro, by continent:

Europe

Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, BAM)

Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, BAM) Bulgaria (Bulgarian lev, BGN)

Bulgaria (Bulgarian lev, BGN) Denmark (Danish krone, DKK)

Denmark (Danish krone, DKK) North Macedonia (Macedonian denar, MKD)

North Macedonia (Macedonian denar, MKD) Sovereign Military Order of Malta (Maltese scudo)[96]

Sovereign Military Order of Malta (Maltese scudo)[96]

Oceania

French Polynesia (CFP franc, XPF)

French Polynesia (CFP franc, XPF) New Caledonia (CFP franc)

New Caledonia (CFP franc) Wallis and Futuna (CFP franc)

Wallis and Futuna (CFP franc)

Africa

Benin (West African CFA franc, XOF)

Benin (West African CFA franc, XOF) Burkina Faso (West African CFA franc)

Burkina Faso (West African CFA franc) Cameroon (Central African CFA franc, XAF)

Cameroon (Central African CFA franc, XAF) Cape Verde (Cape Verdean escudo, CVE)

Cape Verde (Cape Verdean escudo, CVE) Central African Republic (Central African CFA franc)

Central African Republic (Central African CFA franc) Chad (Central African CFA franc)

Chad (Central African CFA franc) Comoros (Comorian franc, KMF)

Comoros (Comorian franc, KMF) Equatorial Guinea (Central African CFA franc)

Equatorial Guinea (Central African CFA franc) Gabon (Central African CFA franc)

Gabon (Central African CFA franc) Guinea-Bissau (West African CFA franc)

Guinea-Bissau (West African CFA franc) Ivory Coast (West African CFA franc)

Ivory Coast (West African CFA franc) Mali (West African CFA franc)

Mali (West African CFA franc) Morocco (Moroccan dirham, MAD) (through a basket of currencies)

Morocco (Moroccan dirham, MAD) (through a basket of currencies) Niger (West African CFA franc)

Niger (West African CFA franc) Republic of the Congo (Central African CFA franc)

Republic of the Congo (Central African CFA franc) São Tomé and Príncipe (São Tomé and Príncipe dobra, STN)

São Tomé and Príncipe (São Tomé and Príncipe dobra, STN) Senegal (West African CFA franc)

Senegal (West African CFA franc) Togo (West African CFA franc)

Togo (West African CFA franc)

Use as reserve currency

[edit]Since its introduction in 1999, the euro has been the second most widely held international reserve currency after the U.S. dollar. The share of the euro as a reserve currency increased from 18% in 1999 to 27% in 2008. Over this period, the share held in U.S. dollar fell from 71% to 64% and that held in RMB fell from 6.4% to 3.3%. The euro inherited and built on the status of the Deutsche Mark as the second most important reserve currency. The euro remains underweight as a reserve currency in advanced economies while overweight in emerging and developing economies: according to the International Monetary Fund[97] the total of euro held as a reserve in the world at the end of 2008 was equal to $1.1 trillion or €850 billion, with a share of 22% of all currency reserves in advanced economies, but a total of 31% of all currency reserves in emerging and developing economies.

The possibility of the euro becoming the first international reserve currency has been debated among economists.[98] Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan gave his opinion in September 2007 that it was "absolutely conceivable that the euro will replace the US dollar as reserve currency, or will be traded as an equally important reserve currency".[99] In contrast to Greenspan's 2007 assessment, the euro's increase in the share of the worldwide currency reserve basket has slowed considerably since 2007 and since the beginning of the Great Recession and Euro area crisis.[97]

Economics

[edit]

Optimal currency area

[edit]In economics, an optimum currency area, or region (OCA or OCR), is a geographical region in which it would maximise economic efficiency to have the entire region share a single currency. There are two models, both proposed by Robert Mundell: the stationary expectations model and the international risk sharing model. Mundell himself advocates the international risk sharing model and thus concludes in favour of the euro.[100] However, even before the creation of the single currency, there were concerns over diverging economies. Before the late-2000s recession it was considered unlikely that a state would leave the euro or the whole zone would collapse.[101] However the Greek government-debt crisis led to former British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw claiming the eurozone could not last in its current form.[102] Part of the problem seems to be the rules that were created when the euro was set up. John Lanchester, writing for The New Yorker, explains it:

The guiding principle of the currency, which opened for business in 1999, were supposed to be a set of rules to limit a country's annual deficit to three per cent of gross domestic product, and the total accumulated debt to sixty per cent of G.D.P. It was a nice idea, but by 2004 the two biggest economies in the euro zone, Germany and France, had broken the rules for three years in a row.[103]

Increasing business cycle divergence across the Eurozone over the last decades implies a decreasing optimum currency area.[104]

Transaction costs and risks

[edit]The most obvious benefit of adopting a single currency is to remove the cost of exchanging currency, theoretically allowing businesses and individuals to consummate previously unprofitable trades. For consumers, banks in the eurozone must charge the same for intra-member cross-border transactions as purely domestic transactions for electronic payments (e.g., credit cards, debit cards and cash machine withdrawals).

Financial markets on the continent are expected to be far more liquid and flexible than they were in the past. The reduction in cross-border transaction costs will allow larger banking firms to provide a wider array of banking services that can compete across and beyond the eurozone. However, although transaction costs were reduced, some studies have shown that risk aversion has increased during the last 40 years in the Eurozone.[105]

Price parity

[edit]Another effect of the common European currency is that differences in prices—in particular in price levels—should decrease because of the law of one price. Differences in prices can trigger arbitrage, i.e., speculative trade in a commodity across borders purely to exploit the price differential. Therefore, prices on commonly traded goods are likely to converge, causing inflation in some regions and deflation in others during the transition. Some evidence of this has been observed in specific eurozone markets.[106]

Macroeconomic stability

[edit]Before the introduction of the euro, some countries had successfully contained inflation, which was then seen as a major economic problem, by establishing largely independent central banks. One such bank was the Bundesbank in Germany; the European Central Bank was modelled on the Bundesbank.[107]

The euro has come under criticism due to its regulation, lack of flexibility and rigidity towards sharing member states on issues such as nominal interest rates.[108] Many national and corporate bonds denominated in euro are significantly more liquid and have lower interest rates than was historically the case when denominated in national currencies. While increased liquidity may lower the nominal interest rate on the bond, denominating the bond in a currency with low levels of inflation arguably plays a much larger role. A credible commitment to low levels of inflation and a stable debt reduces the risk that the value of the debt will be eroded by higher levels of inflation or default in the future, allowing debt to be issued at a lower nominal interest rate.

There is also a cost in structurally keeping inflation lower than in the United States, United Kingdom, and China. The result is that seen from those countries, the euro has become expensive, making European products increasingly expensive for its largest importers; hence export from the eurozone becomes more difficult.

In general, those in Europe who own large amounts of euro are served by high stability and low inflation.

A monetary union means states in that union lose the main mechanism of recovery of their international competitiveness by weakening (depreciating) their currency. When wages become too high compared to productivity in the exports sector, then these exports become more expensive and they are crowded out from the market within a country and abroad. This drives the fall of employment and output in the exports sector and fall of trade and current account balances. Fall of output and employment in the tradable goods sector may be offset by the growth of non-exports sectors, especially in construction and services. Increased purchases abroad and negative current account balances can be financed without a problem as long as credit is cheap.[109] The need to finance trade deficit weakens currency, making exports automatically more attractive in a country and abroad. A state in a monetary union cannot use weakening of currency to recover its international competitiveness. To achieve this a state has to reduce prices, including wages (deflation). This could result in high unemployment and lower incomes as it was during the euro area crisis.[110]

Trade

[edit]The euro increased price transparency and stimulated cross-border trade.[111] A 2009 consensus from the studies of the introduction of the euro concluded that it has increased trade within the eurozone by 5% to 10%,[112] and a meta-analysis of all available studies on the effect of introduction of the euro on increased trade suggests that the prevalence of positive estimates is caused by publication bias and that the underlying effect may be negligible.[113] Although a more recent meta-analysis shows that publication bias decreases over time and that there are positive trade effects from the introduction of the euro, as long as results from before 2010 are taken into account. This may be because of the inclusion of the 2008 financial crisis and ongoing integration within the EU.[114] Furthermore, older studies based on certain methods of analysis of main trends reflecting general cohesion policies in Europe that started before, and continue after implementing the common currency find no effect on trade.[115][116] These results suggest that other policies aimed at European integration might be the source of observed increase in trade. According to Barry Eichengreen, studies disagree on the magnitude of the effect of the euro on trade, but they agree that it did have an effect.[111]

Investment

[edit]Physical investment seems to have increased by 5% in the eurozone due to the introduction.[117] Regarding foreign direct investment, a study found that the intra-eurozone FDI stocks have increased by about 20% during the first four years of the EMU.[118] Concerning the effect on corporate investment, there is evidence that the introduction of the euro has resulted in an increase in investment rates and that it has made it easier for firms to access financing in Europe. The euro has most specifically stimulated investment in companies that come from countries that previously had weak currencies. A study found that the introduction of the euro accounts for 22% of the investment rate after 1998 in countries that previously had a weak currency.[119]

Inflation

[edit]

The introduction of the euro has led to extensive discussion about its possible effect on inflation. In the short term, there was a widespread impression in the population of the eurozone that the introduction of the euro had led to an increase in prices, but this impression was not confirmed by general indices of inflation and other studies.[120][121] A study of this paradox found that this was due to an asymmetric effect of the introduction of the euro on prices: while it had no effect on most goods, it had an effect on cheap goods which have seen their price round up after the introduction of the euro. The study found that consumers based their beliefs on inflation of those cheap goods which are frequently purchased.[122] It has also been suggested that the jump in small prices may be because prior to the introduction, retailers made fewer upward adjustments and waited for the introduction of the euro to do so.[123] Based on the introduction of the euro as the official currency in Croatia in 2023, the ECB argues that inflation due to a change of currency is a one-time effect of limited impact.[124]

Exchange rate risk

[edit]One of the advantages of the adoption of a common currency is the reduction of the risk associated with changes in currency exchange rates.[111] It has been found that the introduction of the euro created "significant reductions in market risk exposures for nonfinancial firms both in and outside Europe".[125] These reductions in market risk "were concentrated in firms domiciled in the eurozone and in non-euro firms with a high fraction of foreign sales or assets in Europe".

Financial integration

[edit]The introduction of the euro increased financial integration within Europe, which helped stimulate growth of a European securities market (bond markets are characterized by economies of scale dynamics).[111] According to a study on this question, it has "significantly reshaped the European financial system, especially with respect to the securities markets [...] However, the real and policy barriers to integration in the retail and corporate banking sectors remain significant, even if the wholesale end of banking has been largely integrated."[126] Specifically, the euro has significantly decreased the cost of trade in bonds, equity, and banking assets within the eurozone.[127] On a global level, there is evidence that the introduction of the euro has led to an integration in terms of investment in bond portfolios, with eurozone countries lending and borrowing more between each other than with other countries.[128] Financial integration made it cheaper for European companies to borrow.[111] Banks, firms and households could also invest more easily outside of their own country, thus creating greater international risk-sharing.[111]

Effect on interest rates

[edit]

As of January 2014, and since the introduction of the euro, interest rates of most member countries (particularly those with a weak currency) have decreased. Some of these countries had the most serious sovereign financing problems.

The effect of declining interest rates, combined with excess liquidity continually provided by the ECB, made it easier for banks within the countries in which interest rates fell the most, and their linked sovereigns, to borrow significant amounts (above the 3% of GDP budget deficit imposed on the eurozone initially) and significantly inflate their public and private debt levels.[129] Following the 2008 financial crisis, governments in these countries found it necessary to bail out or nationalise their privately held banks to prevent systemic failure of the banking system when underlying hard or financial asset values were found to be grossly inflated and sometimes so nearly worthless there was no liquid market for them.[130] This further increased the already high levels of public debt to a level the markets began to consider unsustainable, via increasing government bond interest rates, leading to the euro area crisis.

Price convergence

[edit]The evidence on the convergence of prices in the eurozone with the introduction of the euro is mixed. Several studies failed to find any evidence of convergence following the introduction of the euro after a phase of convergence in the early 1990s.[131][132] Other studies have found evidence of price convergence,[133][134] in particular for cars.[135] A possible reason for the divergence between the different studies is that the processes of convergence may not have been linear, slowing down substantially between 2000 and 2003, and resurfacing after 2003 as suggested by a recent study (2009).[136]

Tourism

[edit]A study suggests that the introduction of the euro has had a positive effect on the amount of tourist travel within the EMU, with an increase of 6.5%.[137]

Exchange rates

[edit]Flexible exchange rates

[edit]The ECB targets interest rates rather than exchange rates and in general, does not intervene on the foreign exchange rate markets. This is because of the implications of the Mundell–Fleming model, which implies a central bank cannot (without capital controls) maintain interest rate and exchange rate targets simultaneously, because increasing the money supply results in a depreciation of the currency. In the years following the Single European Act, the EU has liberalised its capital markets and, as the ECB has inflation targeting as its monetary policy, the exchange-rate regime of the euro is floating.

Against other major currencies

[edit]The euro is the second-most widely held reserve currency after the U.S. dollar. After its introduction on 4 January 1999 its exchange rate against the other major currencies fell reaching its lowest exchange rates in 2000 (3 May vs sterling, 25 October vs the U.S. dollar, 26 October vs Japanese yen). Afterwards it regained and its exchange rate reached its historical highest point in 2008 (15 July vs US dollar, 23 July vs Japanese yen, 29 December vs sterling). With the onset of the 2008 financial crisis, the euro initially fell, to regain later. Despite pressure due to the euro area crisis, the euro remained stable.[138] In November 2011 the euro's exchange rate index – measured against currencies of the bloc's major trading partners – was trading almost two percent higher on the year, approximately at the same level as it was before the crisis began in 2007.[139] In mid July 2022, the euro and the US dollar traded at par for a short period of time during an episode of dollar appreciation.[20] On 8 October 2025, it recorded a new high against the Japanese yen during a long period of depreciation of the latter.[140]

- Current and historical exchange rates against 30 other currencies (European Central Bank): link

| Current EUR exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK PLN |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK PLN |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK PLN |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY GBP HKD JPY USD SEK PLN |

Political considerations

[edit]Besides the economic motivations to the introduction of the euro, its creation was also partly justified as a way to foster a closer sense of joint identity between European citizens. Statements about this goal were for instance made by Wim Duisenberg, European Central Bank Governor, in 1998,[141] Laurent Fabius, French Finance Minister, in 2000,[142] and Romano Prodi, President of the European Commission, in 2002.[143] However, 15 years after the introduction of the euro, a study found no evidence that it has had any effect on a shared sense of European identity.[144]

Public support for the euro by EU member state, according to a Eurobarometer opinion poll in 2024:[145]

Eurozone

[edit]| Country | For % | Against % |

|---|---|---|

| 66 | 27 | |

| 82 | 15 | |

| 71 | 24 | |

| 80 | 16 | |

| 90 | 8 | |

| 7 | ||

| 74 | 20 | |

| 81 | 14 | |

| 80 | 16 | |

| 88 | 7 | |

| 70 | 23 | |

| 85 | 8 | |

| 78 | 15 | |

| 90 | 8 | |

| 89 | ||

| 84 | 13 | |

| 81 | 13 | |

| 86 | 8 | |

| 92 | 7 | |

| 83 | 11 |

Countries not using the euro

[edit]| Country | For % | Against % |

|---|---|---|

| 37 | 47 | |

| 30 | 62 | |

| 34 | 58 | |

| 65 | 28 | |

| 36 | 51 | |

| 54 | 37 | |

| 37 | 56 |

Euro in various official EU languages

[edit]The formal titles of the currency are euro for the major unit and cent for the minor (one-hundredth) unit and for official use in most eurozone languages; according to the ECB, all languages should use the same spelling for the nominative singular.[146] This may contradict normal rules for word formation in some languages.

Official practice for English-language EU legislation is to use the words euro and cent as both singular and plural.[147] This practice is confirmed by the Directorate-General for Translation,[h] which states that the plural forms euro and cent should also be used in English.[149] Bulgaria has negotiated an exception; euro in the Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet is spelled eвро (evro) and not *eуро (*euro) in all official documents.[150] In the Greek script the term ευρώ (evró) is used; the Greek "cent" coins are denominated in λεπτό/ά (leptó/á). The word "euro" is pronounced differently according to pronunciation rules in the individual languages applied; in German [ˈɔʏʁo], in English /ˈɪuroʊ/, in French [øʁo], etc.

In summary:

| Language(s) | Name | IPA |

|---|---|---|

| In most EU languages | euro | Croatian: [ěuro], Czech: [ˈɛuro], Danish: [ˈœwʁo], Dutch: [ˈøːroː], Estonian: [ˈeu̯ro], Finnish: [ˈeu̯ro], French: [øʁo], Italian: [ˈɛuro], Polish: [ˈɛwrɔ], Portuguese: [ˈewɾɔ] or [ˈewɾu], Slovak: [ˈewrɔ], Spanish: [ˈewɾo] |

| Bulgarian | евро evro | Bulgarian: [ˈɛvro] |

| German | Euro | [ˈɔʏʁo] |

| Greek | ευρώ evró | [eˈvro] |

| Hungarian | euró | [ˈɛuroː] or [ˈɛu̯roː] |

| Latvian | euro or eiro | [ɛìro] |

| Lithuanian | euras | [ˈɛʊrɐs] |

| Maltese | ewro | [ˈɛʊ̯rɔ] |

| Slovene | evro | [ˈéːʋrɔ] |

For local phonetics, cent, use of plural and amount formatting (€6,00 or 6.00 €), see Language and the euro.

See also

[edit]- Captain Euro – Comics character

- The Raspberry Ice Cream War – Children's comic book published by EUCom

- Euro area crisis – Multi-year debt crisis in multiple EU countries, 2009–2010

- Causes of the euro area crisis

- Proposed long-term solutions for the eurozone crisis – Proposals to resolve the 2009/10 debt crisis

- List of acronyms associated with the eurozone crisis

- Currency union – Agreement involving states sharing a single currency

- Digital euro – Central bank digital currency project

- Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union – Economic union and policies

- European integration – Process of political, economic, social, and cultural integration of states in and around Europe

- History of the European Union

- List of circulating currencies

- List of currencies in Europe

- Withdrawal from the eurozone – Member state ceases use of the euro as its currency

Notes

[edit]- ^ Official documents and legislation refer to the euro as "the single currency".[1]

- ^ excluding Northern Cyprus

- ^ excluding French Polynesia, New Caledonia and Wallis and Futuna

- ^ excluding Dutch Caribbean

- ^ See Montenegro and the euro.

- ^ by means of Council Regulation 2866/98 (EC) of 31 December 1998.

- ^ by Council Regulation 1478/2000 (EC) of 19 June 2000.

- ^ Prior to Brexit, the style guide advised conventional plurals in English.[148]

References

[edit]- ^ "Council Regulation (EC) No 1103/97 of 17 June 1997 on certain provisions relating to the introduction of the euro". Official Journal L 162, 19 June 1997 P. 0001 – 0003. European Communities. 19 June 1997. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ a b "ECB Statistical Data Warehouse, Reports>ECB/Eurosystem policy>Banknotes and coins statistics>1.Euro banknotes>1.1 Quantities". European Central Bank. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Walsh, Alistair (29 May 2017). "Italy to stop producing 1- and 2-cent coins". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ^ "Po 1. júli 2022 budú končiť na Slovensku jedno a dvojcentové mince" [One and two cent coins will end in Slovakia after 1 July 2022]. bystricoviny.sk (in Slovak). 29 May 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Euro kasutusele võtmise ja eurodes tehtavate sularahamaksete arveldamise seadus–Riigi Teataja" [Act on the Introduction of the Euro and Settlement of Cash Payments in Euros–Riigi Teataja]. www.riigiteataja.ee (in Estonian). Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ "Paverskite smulkias monetas istorijos dalimi: proginė moneta, skirta gynybai, laukia Jūsų!". Bank of Lithuania (in Lithuanian). 11 April 2025. Retrieved 1 May 2025.

- ^ "Inflation and consumer prices".

- ^ "The euro". European Commission website. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ a b "What is the euro area?". European Commission website. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Population on 1 January". Eurostat.

- ^ "IMF Data – Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserve – At a Glance". International Monetary Fund. 23 December 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ "Foreign exchange turnover in April 2013: preliminary global results" (PDF). Bank for International Settlements. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ "Triennial Central Bank Survey 2007" (PDF). BIS. 19 December 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ Aristovnik, Aleksander; Čeč, Tanja (30 March 2010). "Compositional Analysis of Foreign Currency Reserves in the 1999–2007 Period. The Euro vs. The Dollar As Leading Reserve Currency" (PDF). Munich Personal RePEc Archive, Paper No. 14350. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Boesler, Matthew (11 November 2013). "There Are Only Two Real Threats to the US Dollar's Status As The International Reserve Currency". Business Insider. Retrieved 8 December 2013.

- ^ "1.2 Euro banknotes, values". European Central Bank Statistical Data Warehouse. 14 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ "2.2 Euro coins, values". European Central Bank Statistical Data Warehouse. 14 January 2020. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Madrid European Council (12/95): Conclusions". European Parliament. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ "Initial changeover (2002)". European Central Bank. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Euro Falls Near Parity With Dollar, a Threshold Watched Closely by Investors". The New York Times. 12 July 2022. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "US Dollar to Euro Exchange Rate Chart". XE.com. Retrieved 1 October 2025.

- ^ "The Euro". European Central Bank. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "Banknotes and Coins". European Central Bank. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "Payment Systems". European Central Bank. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "The Euro". European Commission. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- ^ Nice, Treaty of. "Treaty of Nice". About Parliament. European Parliament. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "By agreement of the EU Council". Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Monetary Agreement between the European Union and the Principality of Andorra". Official Journal of the European Union. 17 December 2011. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ "By monetary agreement between France (acting for the EC) and Monaco". Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "By monetary agreement between Italy (acting for the EC) and San Marino". Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "By monetary agreement between Italy (acting for the EC) and Vatican City". Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Theodoulou, Michael (27 December 2007). "Euro reaches field that is for ever England". The Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- ^ "By UNMIK administration direction 1999/2". Unmikonline.org. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Bulgaria ready to use the euro from 1 January 2026: Council takes final steps". European Council. Retrieved 8 July 2025.

- ^ Parliament of the United Kingdom (12 March 1998). "Volume: 587, Part: 120 (12 Mar 1998: Column 391, Baroness Williams of Crosby)". House of Lords Hansard. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "How to use the euro name and symbol". European Commission. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ European Commission. "Spelling of the words "euro" and "cent" in official Community languages as used in Community Legislative acts" (PDF). Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ^ European Commission Directorate-General for Translation. "English Style Guide: A handbook for authors and translators in the European Commission" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2008.; European Union. "Interinstitutional style guide, 7.3.3. Rules for expressing monetary units". Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ "Common sides of euro coins". Europa. European Commission. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Ireland to round to nearest 5 cents starting October 28". 27 October 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- ^ "Rounding". Central Bank of Ireland.

- ^ European Commission (January 2007). "Euro cash: five and familiar". Europa. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ Pop, Valentina (22 March 2010) "Commission frowns on shop signs that say: '€500 notes not accepted'", EU Observer

- ^ European Commission (15 February 2003). "Commission communication: The introduction of euro banknotes and coins one year after COM(2002) 747". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- ^ "Robert Kalina, designer of the euro banknotes, at work at the Oesterreichische Nationalbank in Vienna". European Central Bank. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Schmid, John (3 August 2001). "Etching the Notes of a New European Identity". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- ^ a b "Banknotes". European Central Bank. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "ECB to redesign euro banknotes by 2024". European Central Bank. 6 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Scheller, Hanspeter K. (2006). The European Central Bank: History, Role and Functions (PDF) (2nd ed.). European Central Bank. p. 103. ISBN 978-92-899-0027-0.

Since 1 January 2002, the NCBs and the ECB have issued euro banknotes on a joint basis.

- ^

"Capital Subscription". European Central Bank. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

The NCBs' shares in this capital are calculated using a key which reflects the respective country's share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU – in equal weightings. The ECB adjusts the shares every five years and whenever a new country joins the EU. The adjustment is done on the basis of data provided by the European Commission.

- ^ "Denominations Europa series €5". European Central Bank. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Denominations Europa series €10". European Central Bank. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Denominations Europa series €20". European Central Bank. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Denominations Europa series €50". European Central Bank. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Denominations Europa series €100". European Central Bank. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Denominations Europa series €200". European Central Bank. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Regulation (EC) No 2560/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 December 2001 on cross-border payments in euro". EUR-lex – European Communities, Publications office, Official Journal L 344, 28 December 2001 P. 0013 – 0016. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ "Cross border payments in the EU, Euro Information, The Official Treasury Euro Resource". United Kingdom Treasury. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ European Central Bank. "TARGET". Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Use of the euro". European Central Bank. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ "Treaty on European Union (Maastricht Treaty)". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ Dyson, K., & Featherstone, K. (1999). *The Road to Maastricht: Negotiating Economic and Monetary Union*. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Convergence Criteria". European Central Bank. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ Buti, M., & Sapir, A. (2002). *EMU and Economic Policy in Europe: The Challenge of the Early Years*. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ^ "Protocol on certain provisions relating to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ George, S. (1998). *An Awkward Partner: Britain in the European Community* (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Germain Pirlot 'uitvinder' van de euro" (in Dutch). De Zeewacht. 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "Unready for blast-off". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 28 August 2025.

- ^ "The euro, our currency | A symbol for the European currency" (PDF). European Commission. 18 March 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ a b Directorate-General for Communication. "Institutions, law, budget | The Euro | Design". European Union. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ "Position of the ISO code or euro sign in amounts". Interinstitutional style guide. Bruxelles, Belgium: Europa Publications Office. 5 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ George Matlock (16 February 2010). "Peripheral euro zone government bond spreads widen". Reuters. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "Acropolis now". The Economist. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ^ European Debt Crisis Fast Facts, CNN Library (last updated 22 January 2017).

- ^ Ricardo Reis, Looking for a Success in the Euro Crisis Adjustment Programs: The Case of Portugal, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Brookings Institution (Fall 2015), p. 433.

- ^ "Efsf, come funziona il fondo salvastati europeo". 4 November 2011.

- ^ "The politics of the Maastricht convergence criteria". VoxEU. 15 April 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ "State of the Union: Can the euro zone survive its debt crisis?" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 1 March 2011. p. 4. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "S&P downgrades euro zone's EFSF bailout fund". Reuters. 16 January 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Delamaide, Darrell (24 July 2012). "Euro crisis brings world to brink of depression". MarketWatch. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Lindner, Fabian, "Germany would do well to heed the Moody's warning shot", The Guardian, 24 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Buergin, Rainer, "Germany, Juncker Push Back After Moody's Rating Outlook Cuts Archived 28 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine", washpost.bloomberg, 24 July 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ a b Population Reference Bureau. "2013 World Population Data Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ "Sovereign Base areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia on Cyprus". Commonwealth Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ "Cuba to adopt euro in foreign trade". BBC News. 8 November 1998. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ "US row leads Syria to snub dollar". BBC News. 14 February 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2008.

- ^ Rosati, Andrew; Zerpa, Fabiola (17 October 2018). "Dollars Are Out, Euros Are in as U.S. Sanctions Sting Venezuela". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: A Critical Review of Sterp". 17 April 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ "1 euro equivale a 24.500 dobras" [1 euro is equivalent to 24,500 dobras] (in Portuguese). Téla Nón. 4 January 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ^ "Annual report on exchange arrangements and exchange restrictions, 2023" (PDF).

- ^ "The euro in global foreign exchange reserves and exchange rate anchoring" (PDF).

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. REPUBLIC OF NORTH MACEDONIA".

- ^ "Transition to a more flexible exchange rate system". Archived from the original on 25 March 2025. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ "Retrieved 3 October 2017".

- ^ "Numismatica". Ordine di Malta Italia. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) – Updated COFER tables include first quarter 2009 data. June 30, 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ "Will the Euro Eventually Surpass the Dollar As Leading International Reserve Currency?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "Euro could replace dollar as top currency – Greenspan". Reuters. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ Mundell, Robert (1970) [published 1973]. "A Plan for a European Currency". In Johnson, H. G.; Swoboda, A. K. (eds.). The Economics of Common Currencies – Proceedings of Conference on Optimum Currency Areas. 1970. Madrid. London: Allen and Unwin. pp. 143–172. ISBN 9780043320495.

- ^ Eichengreen, Barry (14 September 2007). "The Breakup of the Euro Area by Barry Eichengreen". NBER Working Paper (w13393). SSRN 1014341.

- ^ "Greek debt crisis: Straw says eurozone 'will collapse'". BBC News. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ John Lanchester, "Euro Science", The New Yorker, 10 October 2011.

- ^ Beck, Krzysztof; Okhrimenko, Iana (2024). "Optimum Currency Area in the Eurozone". Open Economies Review. 36: 197–219. doi:10.1007/s11079-024-09750-z. ISSN 0923-7992.

- ^ Benchimol, J., 2014. Risk aversion in the Eurozone, Research in Economics, vol. 68, issue 1, pp. 40–56.

- ^ Goldberg, Pinelopi K.; Verboven, Frank (2005). "Market Integration and Convergence to the Law of One Price: Evidence from the European Car Market". Journal of International Economics. 65 (1): 49–73. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.494.1517. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2003.12.002. S2CID 26850030.

- ^ de Haan, Jakob (2000). The History of the Bundesbank: Lessons for the European Central Bank. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21723-1.

- ^ Silvia, Steven J (2004). "Is the Euro Working? The Euro and European Labour Markets". Journal of Public Policy. 24 (2): 147–168. doi:10.1017/s0143814x0400008x. JSTOR 4007858. S2CID 152633940.

- ^ Ernest Pytlarczyk, Stefan Kawalec (June 2012). "Controlled Dismantlement of the Euro Area in Order to Preserve the European Union and Single European Market". CASE Center for Social and Economic Research. p. 11. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Martin Feldstein (January–February 2012). "The Failure of the Euro". Foreign Affairs. Chapter: Trading Places.

- ^ a b c d e f Eichengreen, Barry (2019). Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (3rd ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 212–213. doi:10.2307/j.ctvd58rxg. ISBN 978-0-691-19390-8. JSTOR j.ctvd58rxg. S2CID 240840930.

- ^ "The euro's trade effects" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Havránek, Tomáš (2010). "Rose effect and the euro: is the magic gone?" (PDF). Review of World Economics. 146 (2): 241–261. doi:10.1007/s10290-010-0050-1. S2CID 53585674.

- ^ Polák, Petr (2019). "The Euro's Trade Effect: A Meta-Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Economic Surveys. 33 (1): 101–124. doi:10.1111/joes.12264. hdl:10419/174189. ISSN 1467-6419. S2CID 157693449.

- ^ Gomes, Tamara; Graham, Chris; Helliwel, John; Takashi, Kano; Murray, John; Schembri, Lawrence (August 2006). "The Euro and Trade: Is there a Positive Effect?" (PDF). Bank of Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2015.

- ^ H., Berger; V., Nitsch (2008). "Zooming out: The trade effect of the euro in historical perspective" (PDF). Journal of International Money and Finance. 27 (8): 1244–1260. doi:10.1016/j.jimonfin.2008.07.005. hdl:10419/18799. S2CID 53493723.

- ^ "The Impact of the Euro on Investment: Sectoral Evidence" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "Does the single currency affect FDI?" (PDF). AFSE.fr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "The Real Effects of the Euro: Evidence from Corporate Investments" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Paolo Angelini; Francesco Lippi (December 2007). "Did Prices Really Soar after the Euro Cash Changeover? Evidence from ATM Withdrawals" (PDF). International Journal of Central Banking. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ Irmtraud Beuerlein. "Fünf Jahre nach der Euro-Bargeldeinführung –War der Euro wirklich ein Teuro?" [Five years after the introduction of euro cash – Did the euro really make things more expensive?] (PDF) (in German). Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ Dziuda, Wioletta; Mastrobuoni, Giovanni (2009). "The Euro Changeover and Its Effects on Price Transparency and Inflation". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 41 (1): 101–129. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2008.00189.x. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ Hobijn, Bart; Ravenna, Federico; Tambalotti, Andrea (2006). "Quarterly Journal of Economics – Abstract" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics. 121 (3): 1103–1131. doi:10.1162/qjec.121.3.1103.

- ^ Falagiarda, Matteo; Gartner, Christine; Mužić, Ivan; Pufnik, Andreja (7 March 2023). "Has the euro changeover really caused extra inflation in Croatia". ECB. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Bartram, Söhnke M.; Karolyi, G. Andrew (2006). "The impact of the introduction of the Euro on foreign exchange rate risk exposures". Journal of Empirical Finance. 13 (4–5): 519–549. doi:10.1016/j.jempfin.2006.01.002.

- ^ "The Euro and Financial Integration" (PDF). May 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Coeurdacier, Nicolas; Martin, Philippe (2009). "The geography of asset trade and the euro: Insiders and outsiders" (PDF). Journal of the Japanese and International Economies. 23 (2): 90–113. doi:10.1016/j.jjie.2008.11.001. S2CID 55948853.

- ^ Lane, Philip R. (June 2006). "Global Bond Portfolios and EMU". International Journal of Central Banking. 2 (2): 1–23. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.365.4579.

- ^ "Redwood: The origins of the euro crisis". Investmentweek.co.uk. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Farewell, Fair-Weather Euro | IP – Global-Edition". Ip-global.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- ^ "Price setting and inflation dynamics: did EMU matter" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ "Price convergence in the EMU? Evidence from micro data" (PDF). Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "One TV, One Price?" (PDF). Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "One Market, One Money, One Price?" (PDF). Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Gil-Pareja, Salvador, and Simón Sosvilla-Rivero, "Price Convergence in the European Car Market", FEDEA, November 2005.

- ^ Fritsche, Ulrich; Lein, Sarah; Weber, Sebastian (April 2009). "Do Prices in the EMU Converge (Non-linearly)?" (PDF). University of Hamburg, Department Economics and Politics Discussion Papers, Macroeconomics and Finance Series. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ Gil-Pareja, Salvador; Llorca-Vivero, Rafael; Martínez-Serrano, José (May 2007). "The Effect of EMU on Tourism". Review of International Economics. 15 (2): 302–312. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2006.00620.x. S2CID 154503069. SSRN 983231.

- ^ Kirschbaum, Erik. "Schaeuble says markets have confidence in euro". Reuters. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Puzzle over euro's 'mysterious' stability". Reuters. 15 November 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015.

- ^ "Japanese yen (JPY)". www.ecb.europa.eu. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ Global Finance After the Crisis. 2013.

The euro is far more than a medium of exchange. It is part of the identity of a people. It reflects what they have in common now and in the future.

- ^ "European identity". Financial Times. 24 July 2000.

Thanks to the euro, our pockets will soon hold solid evidence of a European identity

- ^ Speech to the European Parliament. 16 January 2002.

The euro is becoming a key element in peoples sense of shared European identity and common destiny.

- ^ Franz Buscha (November 2017). "Can a common currency foster a shared social identity across different nations? The case of the euro" (PDF). European Economic Review. 100: 318–336. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2017.08.011. S2CID 102510742.

- ^ European Commission. Directorate General for Communication. (2024). Public opinion in the European Union: first results : report (Report). Publications Office of the European Union. p. 26. doi:10.2775/437940.

- ^ "European Central Bank, Convergence Report" (PDF). May 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

The euro is the single currency of the member states that have adopted it. To make this singleness apparent, Community law requires a single spelling of the word euro in the nominative singular case in all community and national legislative provisions, taking into account the existence of different alphabets.

- ^ Spelling of the words "euro" and "cent" in official community languages as used in community legislative acts (PDF) (Report). European Commission. Retrieved 12 October 2025.

This spelling without an "s" may be seen as departing from usual English practice for currencies.

- ^ "English Style Guide" (PDF). 5 December 2010. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (archived copy, see §28.8) - ^ "English Style Guide" (PDF). European Commission Directorate-General for Translation. August 2025. p. 53. Retrieved 12 October 2025.

The euro: Like any other currency name in English, the word 'euro' is written in lower case with no initial capital. The plural of 'euro' is 'euro' (without 's'). The invariable plural form 'cent' is also preferred and is compulsory in legal acts

- ^ Elena Koinova (19 October 2007). ""Evro" Dispute Over – Portuguese Foreign Minister – Bulgaria". The Sofia Echo. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Bartram, Söhnke M.; Taylor, Stephen J.; Wang, Yaw-Huei (May 2007). "The Euro and European Financial Market Dependence" (PDF). Journal of Banking and Finance. 51 (5): 1461–1481. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.07.014. SSRN 924333.

- Bartram, Söhnke M.; Karolyi, G. Andrew (October 2006). "The Impact of the Introduction of the Euro on Foreign Exchange Rate Risk Exposures". Journal of Empirical Finance. 13 (4–5): 519–549. doi:10.1016/j.jempfin.2006.01.002. SSRN 299641.

- Baldwin, Richard; Wyplosz, Charles (2004). The Economics of European Integration. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-710394-1.

- Buti, Marco; Deroose, Servaas; Gaspar, Vitor; Nogueira Martins, João (2010). The Euro. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-92-79-09842-0.

- Jordan, Helmuth (2010). "Fehlschlag Euro". Dorrance Publishing. Archived from the original on 16 September 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Simonazzi, A.; Vianello, F. (2001). "Financial Liberalization, the European Single Currency and the Problem of Unemployment". In Franzini, R.; Pizzuti, R.F. (eds.). Globalization, Institutions and Social Cohesion. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-67741-3.

External links

[edit]Characteristics and Administration

Symbol, Design, and Legal Status

The euro symbol (€) derives from the Greek letter epsilon (ε), representing the first letter of "Europe," with two parallel horizontal lines symbolizing stability.[5] The symbol was officially adopted following a public competition and design process initiated in the mid-1990s, reflecting Europe's cultural heritage and economic aspirations.[6] It entered widespread use alongside the euro's launch as an electronic currency on January 1, 1999.[7] Euro banknotes feature designs inspired by architectural styles from seven epochs of European history: Classical, Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo, Age of Iron and Glass, and Modern 20th century, without depicting specific existing structures to avoid national favoritism.[8] The obverse side includes windows and gateways symbolizing openness and cooperation, while the reverse shows bridges representing connectivity across periods.[9] The Europa series, introduced progressively since 2013, incorporates enhanced security features like holograms and watermarks while retaining core design elements.[10] Euro coins consist of eight denominations from 1 cent to 2 euros, with a common reverse side depicting Europe's map, stars of the EU flag, and denomination values, managed uniformly by the European Central Bank.[11] The obverse side varies by issuing country, featuring national symbols, historical figures, or motifs approved by the ECB to ensure compatibility.[12] In the 20 euro area member states, the euro holds exclusive legal tender status, obligating creditors to accept euro banknotes and coins at full face value for transactions unless specific contractual agreements specify otherwise.[13] This status, enshrined in Article 128(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, applies uniformly across the eurozone, prohibiting parallel currencies and ensuring the euro's role as the sole medium of payment.[14] Physical euro notes and coins became legal tender on January 1, 2002, replacing national currencies at dual circulation rates until mid-February 2002.[7]Governance and Monetary Policy