Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Data structure

View on Wikipedia

In computer science, a data structure is a data organization and storage format that is usually chosen for efficient access to data.[1][2][3] More precisely, a data structure is a collection of data values, the relationships among them, and the functions or operations that can be applied to the data,[4] i.e., it is an algebraic structure about data.

Usage

[edit]Data structures serve as the basis for abstract data types (ADT). The ADT defines the logical form of the data type. The data structure implements the physical form of the data type.[5]

Various types of data structures are suited to different kinds of applications, and some are highly defined to specific tasks. For example, relational databases commonly use B-tree indice for data retrieval,[6] while compiler implementations usually use hash tables to look up identifiers.[7]

Data structures provide a means to manage large amounts of data efficiently for uses such as large databases and internet indexing services. Usually, efficient data structures are key to designing efficient algorithms. Some formal design methods and programming languages emphasize data structures, rather than algorithms, as the key organizing factor in software design. Data structures can be used to organize the storage and retrieval of data stored in both main memory and secondary memory.[8]

Implementation

[edit]Data structures can be implemented using a variety of programming languages and techniques, but they all share the common goal of efficiently organizing and storing data.[9] Data structures are generally based on the ability of a computer to fetch and store data at any place in its memory, specified by a pointer—a bit string, representing a memory address, that can be itself stored in memory and manipulated by the program. Thus, the array and record data structures are based on computing the addresses of data items with arithmetic operations, while the linked data structures are based on storing addresses of data items within the structure itself. This approach to data structuring has profound implications for the efficiency and scalability of algorithms. For instance, the contiguous memory allocation in arrays facilitates rapid access and modification operations, leading to optimized performance in sequential data processing scenarios.[10]

The implementation of a data structure usually requires writing a set of procedures that create and manipulate instances of that structure. The efficiency of a data structure cannot be analyzed separately from those operations. This observation motivates the theoretical concept of an abstract data type, a data structure that is defined indirectly by the operations that may be performed on it, and the mathematical properties of those operations (including their space and time cost).[11]

Examples

[edit]

There are numerous types of data structures, generally built upon simpler primitive data types. Well known examples are:[12]

- An array is a number of elements in a specific order, typically all of the same type (depending on the language, individual elements may either all be forced to be the same type, or may be of almost any type). Elements are accessed using an integer index to specify which element is required. Typical implementations allocate contiguous memory words for the elements of arrays (but this is not always a necessity). Arrays may be fixed-length or resizable.

- A linked list (also just called list) is a linear collection of data elements of any type, called nodes, where each node has itself a value, and points to the next node in the linked list. The principal advantage of a linked list over an array is that values can always be efficiently inserted and removed without relocating the rest of the list. Certain other operations, such as random access to a certain element, are however slower on lists than on arrays.

- A record (also called tuple or struct) is an aggregate data structure. A record is a value that contains other values, typically in fixed number and sequence and typically indexed by names. The elements of records are usually called fields or members. In the context of object-oriented programming, records are known as plain old data structures to distinguish them from objects.[13]

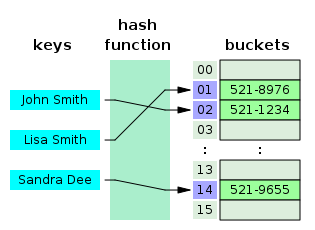

- Hash tables, also known as hash maps, are data structures that provide fast retrieval of values based on keys. They use a hashing function to map keys to indexes in an array, allowing for constant-time access in the average case. Hash tables are commonly used in dictionaries, caches, and database indexing. However, hash collisions can occur, which can impact their performance. Techniques like chaining and open addressing are employed to handle collisions.

- Graphs are collections of nodes connected by edges, representing relationships between entities. Graphs can be used to model social networks, computer networks, and transportation networks, among other things. They consist of vertices (nodes) and edges (connections between nodes). Graphs can be directed or undirected, and they can have cycles or be acyclic. Graph traversal algorithms include breadth-first search and depth-first search.

- Stacks and queues are abstract data types that can be implemented using arrays or linked lists. A stack has two primary operations: push (adds an element to the top of the stack) and pop (removes the topmost element from the stack), that follow the Last In, First Out (LIFO) principle. Queues have two main operations: enqueue (adds an element to the rear of the queue) and dequeue (removes an element from the front of the queue) that follow the First In, First Out (FIFO) principle.

- Trees represent a hierarchical organization of elements. A tree consists of nodes connected by edges, with one node being the root and all other nodes forming subtrees. Trees are widely used in various algorithms and data storage scenarios. Binary trees (particularly heaps), AVL trees, and B-trees are some popular types of trees. They enable efficient and optimal searching, sorting, and hierarchical representation of data.

- A trie, or prefix tree, is a special type of tree used to efficiently retrieve strings. In a trie, each node represents a character of a string, and the edges between nodes represent the characters that connect them. This structure is especially useful for tasks like autocomplete, spell-checking, and creating dictionaries. Tries allow for quick searches and operations based on string prefixes.

Language support

[edit]Most assembly languages and some low-level languages, such as BCPL (Basic Combined Programming Language), lack built-in support for data structures. On the other hand, many high-level programming languages and some higher-level assembly languages, such as MASM, have special syntax or other built-in support for certain data structures, such as records and arrays. For example, the C (a direct descendant of BCPL) and Pascal languages support structs and records, respectively, in addition to vectors (one-dimensional arrays) and multi-dimensional arrays.[14][15]

Most programming languages feature some sort of library mechanism that allows data structure implementations to be reused by different programs. Modern languages usually come with standard libraries that implement the most common data structures. Examples are the C++ Standard Template Library, the Java Collections Framework, and the Microsoft .NET Framework.

Modern languages also generally support modular programming, the separation between the interface of a library module and its implementation. Some provide opaque data types that allow clients to hide implementation details. Object-oriented programming languages, such as C++, Java, and Smalltalk, typically use classes for this purpose.

Many known data structures have concurrent versions which allow multiple computing threads to access a single concrete instance of a data structure simultaneously.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2009). Introduction to Algorithms, Third Edition (3rd ed.). The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262033848.

- ^ Black, Paul E. (15 December 2004). "data structure". In Pieterse, Vreda; Black, Paul E. (eds.). Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures [online]. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ "Data structure". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 17 April 2017. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ Wegner, Peter; Reilly, Edwin D. (2003-08-29). Encyclopedia of Computer Science. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 507–512. ISBN 978-0470864128.

- ^ "Abstract Data Types". Virginia Tech - CS3 Data Structures & Algorithms. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2023-02-15.

- ^ Gavin Powell (2006). "Chapter 8: Building Fast-Performing Database Models". Beginning Database Design. Wrox Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7645-7490-0. Archived from the original on 2007-08-18.

- ^ "1.5 Applications of a Hash Table". University of Regina - CS210 Lab: Hash Table. Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ "When data is too big to fit into the main memory". Indiana University Bloomington - Data Structures (C343/A594). 2014. Archived from the original on 2018-04-10.

- ^ Vaishnavi, Gunjal; Shraddha, Gavane; Yogeshwari, Joshi (2021-06-21). "Survey Paper on Fine-Grained Facial Expression Recognition using Machine Learning" (PDF). International Journal of Computer Applications. 183 (11): 47–49. doi:10.5120/ijca2021921427.

- ^ Nievergelt, Jürg; Widmayer, Peter (2000-01-01), Sack, J. -R.; Urrutia, J. (eds.), "Chapter 17 - Spatial Data Structures: Concepts and Design Choices", Handbook of Computational Geometry, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 725–764, ISBN 978-0-444-82537-7, retrieved 2023-11-12

- ^ Dubey, R. C. (2014). Advanced biotechnology : For B Sc and M Sc students of biotechnology and other biological sciences. New Delhi: S Chand. ISBN 978-81-219-4290-4. OCLC 883695533.

- ^ Seymour, Lipschutz (2014). Data structures (Revised first ed.). New Delhi, India: McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 9781259029967. OCLC 927793728.

- ^ Walter E. Brown (September 29, 1999). "C++ Language Note: POD Types". Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2016-12-03. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "The GNU C Manual". Free Software Foundation. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- ^ Van Canneyt, Michaël (September 2017). "Free Pascal: Reference Guide". Free Pascal.

- ^ Mark Moir and Nir Shavit. "Concurrent Data Structures" (PDF). cs.tau.ac.il. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-01.

Bibliography

[edit]- Peter Brass, Advanced Data Structures, Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0521880374

- Donald Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming, vol. 1. Addison-Wesley, 3rd edition, 1997, ISBN 978-0201896831

- Dinesh Mehta and Sartaj Sahni, Handbook of Data Structures and Applications, Chapman and Hall/CRC Press, 2004, ISBN 1584884355

- Niklaus Wirth, Algorithms and Data Structures, Prentice Hall, 1985, ISBN 978-0130220059

Further reading

[edit]- Open Data Structures by Pat Morin

- G. H. Gonnet and R. Baeza-Yates, Handbook of Algorithms and Data Structures - in Pascal and C, second edition, Addison-Wesley, 1991, ISBN 0-201-41607-7

- Ellis Horowitz and Sartaj Sahni, Fundamentals of Data Structures in Pascal, Computer Science Press, 1984, ISBN 0-914894-94-3

External links

[edit]Data structure

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

A data structure is a specialized format for organizing, processing, retrieving, and storing data in a computer so that it can be accessed and modified efficiently. This organization allows programs to perform operations on data in a manner that aligns with the requirements of specific algorithms and applications.[1] Key characteristics of data structures include their mode of organization, such as sequential arrangements for ordered access or hierarchical setups for relational data; the set of supported operations, typically encompassing insertion, deletion, search, and traversal; and efficiency considerations, which involve trade-offs between time complexity for operations and space usage in memory. These properties ensure that data structures are tailored to optimize performance for particular computational tasks, balancing factors like access speed and resource consumption.[2][7] The concept of data structures originated in the mid-20th century amid the development of early computing systems, with the term gaining widespread recognition in the 1960s through foundational works in algorithm analysis. Notably, Donald Knuth's "The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1" (1968) systematized the study of data structures, emphasizing their role in efficient programming.[5] Data structures presuppose a basic understanding of data representation and algorithmic processes, yet they are indispensable for computation because they enable scalable and performant solutions to complex problems by structuring information in ways that support algorithmic efficiency. While related to abstract data types—which specify behaviors independently of implementation—data structures focus on concrete organizational mechanisms.[8]Abstract Data Types vs. Data Structures

An abstract data type (ADT) is a mathematical model that defines a data type solely in terms of its behavioral properties, specifying the operations that can be performed on it and the axioms governing those operations, without detailing any underlying representation or implementation.[9] For instance, a stack ADT is characterized by operations such as push (adding an element to the top) and pop (removing the top element), along with axioms ensuring that popping after pushing retrieves the pushed element in a last-in, first-out manner.[10] This abstraction allows programmers to reason about the data type's functionality independently of how it is stored or manipulated in memory.[11] In contrast, a data structure represents the concrete realization of an ADT, providing a specific way to store and organize data to support the required operations efficiently.[12] For the stack ADT, possible data structures include an array, where elements are stored in contiguous memory locations with a pointer tracking the top, or a linked list, where nodes are dynamically allocated and chained together.[13] The choice of data structure determines aspects like memory usage and access speed but must adhere to the ADT's behavioral specifications to maintain correctness.[14] The primary distinction between ADTs and data structures lies in their focus: ADTs emphasize the "what"—the interface, semantics, and intended behavior—while data structures address the "how"—the physical storage mechanisms and their performance implications.[9] For example, a queue ADT, defined by enqueue (add to rear) and dequeue (remove from front) operations following first-in, first-out semantics, can be implemented using a circular array data structure to optimize space by reusing positions or a linked list to allow unbounded growth without fixed size constraints.[15] This separation promotes modularity, as changes to the data structure do not affect code relying on the ADT interface, provided efficiency guarantees are preserved.[16] The concept of ADTs was formalized in the 1970s to enhance software modularity and abstraction in programming languages, with pioneering work by Barbara Liskov and Stephen Zilles introducing the idea as a way to extend built-in types with user-defined abstractions that hide implementation details.[17] Their approach, detailed in a seminal 1974 paper, argued for treating data types as extensible entities defined by operations and behaviors, influencing modern object-oriented design principles.[18] This evolution shifted programming paradigms from low-level machine concerns toward higher-level, reusable specifications.[19]Classification

Primitive Data Types

Primitive data types represent the fundamental building blocks in programming languages, consisting of simple, indivisible units that store single values without any internal composition. Common examples include integers for whole numbers, floating-point numbers for approximate real values, characters for individual symbols, and booleans for true/false states. These types are predefined by the language using reserved keywords and are not constructed from other data types.[20][21] A key characteristic of primitive data types is their fixed memory allocation, which aligns directly with hardware capabilities for efficiency. For instance, integers and floating-point types often correspond to word sizes in the CPU architecture, such as 32-bit or 64-bit registers, enabling predictable storage and rapid access. They lack nested structure, holding only atomic values, and support basic operations like arithmetic, comparison, and logical manipulations that are implemented via dedicated hardware instructions in the processor's arithmetic logic unit (ALU). This hardware support ensures high performance, as operations on primitives bypass higher-level abstractions and execute at the machine instruction level.[22][23][24] In languages like C++, theint type typically occupies 32 bits for signed integers, providing a range from to (approximately -2.1 billion to 2.1 billion). Similarly, Java's byte type is an 8-bit signed integer with values from -128 to 127, optimized for memory-constrained scenarios like large arrays. These primitives form the essential atoms for constructing more complex data structures, where multiple instances are aggregated to represent collections or relationships.[20]

Composite Data Structures

Composite data structures aggregate primitive data types to form collections capable of handling multiple related data items as a single unit.[25] This aggregation allows programmers to group components of varying types into coherent entities, facilitating the representation of complex information beyond simple scalars.[26] Composite data structures can be classified as homogeneous or heterogeneous based on element types, and as static or dynamic based on size adaptability. Homogeneous composites contain elements of the same primitive type, such as arrays of integers, enabling uniform operations across the collection.[27] In contrast, heterogeneous composites mix different types, like a structure holding a string for name and an integer for age.[25] Static composites have a fixed size determined at compile time, limiting flexibility but ensuring predictable memory usage, while dynamic ones can resize at runtime to accommodate varying data volumes.[28] Examples of composite data structures include records or structs in languages like C, which group related fields such as a person's name and age into a single entity for easier manipulation.[25] In Python, tuples serve as immutable heterogeneous composites, allowing storage of mixed data like coordinates (x, y) without modification after creation.[29] Similarly, in SQL databases, rows function as composite records, combining attributes of different types (e.g., text and numeric) to represent table entries.[30] These structures offer key advantages by enabling the modeling of real-world entities, such as customer profiles, through logical grouping that mirrors domain concepts.[31] They also enhance code organization by reducing the need to manage scattered primitives, promoting maintainability and abstraction in software design.[32]Linear vs. Non-linear Structures

Data structures are classified into linear and non-linear categories based on the topological organization of their elements and the nature of relationships between them. Linear data structures arrange elements in a sequential manner, where each element is connected to its predecessor and successor, forming a single level of linkage. This sequential organization facilitates straightforward traversal from one element to the next, making them ideal for representing ordered data such as lists or queues.[33] Examples include arrays, which provide direct indexing for elements, and linked lists, which rely on pointers for sequential navigation. In contrast, non-linear data structures organize elements in multiple dimensions or hierarchical fashions, allowing for complex interconnections beyond simple sequences. Trees, for instance, establish parent-child relationships among nodes, enabling representation of hierarchical data like file systems or organizational charts. Graphs, on the other hand, permit arbitrary edges between nodes, modeling networked relationships such as social connections or transportation routes. These structures are particularly suited for scenarios involving intricate dependencies or multi-level associations.[34][35] A primary distinction lies in access patterns and traversal requirements. Linear structures often support efficient random access; for example, arrays allow retrieval of any element in constant time, O(1), due to their contiguous memory allocation and index-based addressing. Linked lists, while linear, require sequential traversal starting from the head, resulting in O(n) time for distant elements. Non-linear structures, however, necessitate specialized traversal algorithms such as Depth-First Search (DFS) or Breadth-First Search (BFS) to explore nodes, as there is no inherent linear path; these algorithms systematically visit connected components, with time complexity typically O(V + E) where V is vertices and E is edges.[36][37] The choice between linear and non-linear structures involves key trade-offs in simplicity, flexibility, and complexity. Linear structures are generally simpler to implement and maintain, with predictable memory usage and easier debugging for sequential operations, but they lack the flexibility to efficiently model non-sequential or relational data without additional overhead. Non-linear structures offer greater power for capturing real-world complexities like hierarchies or networks, yet they introduce higher implementation complexity, including challenges in memory management and algorithm design for traversals. These trade-offs must be evaluated based on the specific problem's requirements, such as data relationships and access frequencies.[33]Common Data Structures

Arrays and Linked Lists

Arrays represent a core linear data structure where elements of the same type are stored in contiguous blocks of memory, typically with a fixed size declared at initialization.[38] This contiguous allocation enables direct indexing for access, such as retrieving the element at position i viaarray[i], by computing the address as the base pointer plus i times the size of each element.[38] A primary advantage of arrays is their constant-time O(1) random access, making them ideal for scenarios requiring frequent lookups by index.[39] However, their fixed size limits dynamic resizing without reallocation, and insertions or deletions in the middle necessitate shifting all subsequent elements, incurring O(n) time complexity where n is the number of elements.[40]

Linked lists, in contrast, are dynamic linear structures composed of discrete nodes, each containing the data payload along with one or more pointers referencing adjacent nodes.[41] Unlike arrays, linked lists allocate memory non-contiguously on demand, allowing the size to grow or shrink efficiently without predefined bounds.[42] Common variants include singly-linked lists, where each node points only to the next; doubly-linked lists, with bidirectional pointers for forward and backward traversal; and circular linked lists, where the last node connects back to the first to form a loop.[43] Key advantages lie in their support for O(1) insertions and deletions at known positions, such as the head in a singly-linked list, by simply updating pointers without shifting data.[41] A notable disadvantage is the lack of direct indexing, requiring sequential traversal from the head for searches or access, which takes O(n) time.

When comparing arrays and linked lists, arrays excel in access speed due to O(1) indexing but falter on modifications, where insertions may require O(n) shifts, whereas linked lists facilitate O(1) local changes at the cost of O(n) access and additional overhead from pointer storage, roughly doubling memory per element compared to arrays.[40][44] For instance, inserting a new node after a given node in a singly-linked list involves straightforward pointer adjustments, as shown in the following pseudocode:

To insert new_node after current_node:

new_node.next = current_node.next

current_node.next = new_node

To insert new_node after current_node:

new_node.next = current_node.next

current_node.next = new_node

Trees and Graphs

Trees represent hierarchical relationships in data and are defined as acyclic connected graphs consisting of nodes, where each node except the root has exactly one parent, and the graph has a single root node with leaves at the extremities.[47] A key property of a tree with n nodes is that it contains exactly n-1 edges, ensuring connectivity without cycles.[48] This structure allows for efficient representation of ordered, branching data, distinguishing trees from linear structures by their non-sequential connectivity. Binary trees are a common variant where each node has at most two children, often designated as left and right subtrees.[49] Balanced binary trees, such as AVL trees—named after inventors Adelson-Velsky and Landis—maintain height balance between subtrees to support efficient operations.[50] A prominent example is the binary search tree (BST), which organizes data such that for any node, all values in the left subtree are less than the node's value, and all in the right subtree are greater, facilitating ordered storage and retrieval.[51] Trees find applications in modeling file systems, where directories form hierarchical branches from a root, and in expression parsing, where operators and operands construct syntax trees for evaluation.[52][53] Graphs extend tree structures by allowing cycles and multiple connections, defined as sets of vertices connected by edges that may be directed or undirected, and weighted or unweighted to represent relationships or costs.[54] Unlike trees, graphs can model complex networks with cycles, enabling representations of interconnected entities such as social networks, where vertices denote individuals and edges indicate relationships.[55] Common representations include adjacency lists, which store neighbors for each vertex efficiently for sparse graphs, and adjacency matrices, which use a 2D array to indicate edge presence between vertices.[56] An overview of graph algorithms includes Dijkstra's algorithm for finding shortest paths in weighted graphs with non-negative edge weights, starting from a source vertex and progressively updating distances.[57]Hash Tables and Sets

A hash table is an associative data structure that stores key-value pairs in an array, where a hash function computes an index for each key to enable direct access to the corresponding value.[58] The hash function typically maps keys from a potentially large universe to a smaller fixed range of array indices, such as using the modulo operation for integer keys, where the index is calculated as and is the size of the array.[59] This design allows for efficient storage and retrieval, assuming a well-distributed hash function that minimizes clustering of keys. Collisions occur when distinct keys hash to the same index, which is inevitable due to the pigeonhole principle when the number of keys exceeds the array size.[60] Common resolution strategies include chaining, where each array slot points to a linked list of collided elements, and open addressing, which probes alternative slots using techniques like linear or quadratic probing to insert or find elements.[61] To maintain performance, the load factor—the ratio of stored elements to array size—should be kept below 0.7, triggering resizing and rehashing when exceeded to reduce collision probability.[62] Under uniform hashing assumptions, hash table operations like insertion, deletion, and search achieve average-case time complexity of , though the worst case degrades to if all keys collide due to a poor hash function.[63] Space complexity is , accounting for keys and array slots. These structures are particularly useful for unordered, key-driven access, contrasting with traversal-based navigation in graphs. Sets are unordered collections of unique elements, typically implemented as hash tables where elements serve as keys with implicit null values to enforce duplicates. Core operations include union, which combines elements from two sets, and intersection, which retains only common elements, both leveraging hash table lookups for efficiency. In Java, the HashMap class provides a hash table-based implementation for key-value mappings, supporting null keys and values while automatically handling resizing at a default load factor of 0.75.[64] Similarly, Python's built-in set type uses a hash table for fast membership testing and set operations, ensuring average-time additions and checks for uniqueness.[65]Operations and Analysis

Basic Operations

Data structures support a set of fundamental operations that enable the manipulation and access of stored information, abstracted from their specific implementations through abstract data types (ADTs). These core operations include insertion, which adds an element to the structure; deletion, which removes an element; search or retrieval, which locates a specific element; and traversal, which systematically visits all elements in the structure.[17] The semantics of these operations vary by data structure type to enforce specific behavioral constraints. For stacks, an ADT enforcing last-in, first-out (LIFO) order, insertion is termed push (adding to the top) and deletion is pop (removing from the top), often accompanied by top to retrieve the uppermost element without removal.[17] Queues, adhering to first-in, first-out (FIFO) discipline, use enqueue for insertion at the rear and dequeue for deletion from the front. In trees, traversal operations such as inorder (left-root-right) and preorder (root-left-right) facilitate ordered visits, useful for processing hierarchical data like binary search trees. Error handling is integral to these operations, ensuring robustness by addressing invalid states or inputs. Bounds checking verifies that indices or positions remain within allocated limits, preventing overflows in fixed-size structures like arrays. Null pointer checks detect uninitialized or invalid references, avoiding dereferencing errors in pointer-based structures such as linked lists.[66] Preconditions, such as requiring a structure to be non-full before insertion in fixed-capacity implementations, further safeguard operations by defining valid invocation contexts. These operations were formalized in the 1970s through ADT specifications, with Barbara Liskov and Stephen Zilles introducing structured error mechanisms and operation contracts in 1974 to promote consistent interfaces across implementations.[17] By the 1980s, such standards influenced language designs, emphasizing abstraction for reliable software modularity. While their efficiency varies—detailed in complexity analyses—these operations form the basis for algorithmic design.Time and Space Complexity

Time complexity refers to the computational resources required to execute an operation or algorithm as a function of the input size , typically measured in terms of the number of basic operations performed. It provides a way to evaluate how the runtime scales with larger inputs, independent of hardware specifics.[67] For instance, searching an unsorted array requires examining each element in the worst case, yielding a linear time complexity of , while a hash table lookup averages constant time under uniform hashing assumptions, and a balanced binary search tree search achieves .[68] These notations abstract away constant factors and lower-order terms to focus on dominant growth rates. Space complexity measures the amount of memory used by an algorithm or data structure beyond the input, including auxiliary space for variables, recursion stacks, or additional structures. Arrays require space to store elements contiguously, whereas linked lists demand space for the elements plus for pointers linking nodes, often leading to trade-offs where increased space enables faster operations, such as using extra memory in hash tables to reduce collisions and maintain time.[67] Space-time optimization balances these, as seen in structures like dynamic arrays that allocate extra space to amortize resizing costs. Analysis of time and space complexity employs asymptotic notations to bound performance: Big-O () describes an upper bound on growth, Big-Theta () a tight bound matching both upper and lower limits, and Big-Omega () a lower bound.[69] Evaluations consider worst-case (maximum resources over all inputs), average-case (expected resources under a probability distribution), and amortized analysis (average cost over a sequence of operations). For example, dynamic array resizing incurs cost sporadically but amortizes to per insertion when doubling capacity, using the aggregate method to sum total costs divided by operations.[70] Recurrence relations model divide-and-conquer algorithms' complexities, such as binary search on a sorted array of size , where the time satisfies with base case . Solving via the master theorem or recursion tree yields , as each level halves the problem size over levels, each costing constant work.[71]Implementation Considerations

Language Support

Programming languages vary significantly in their built-in support for data structures, ranging from basic primitives in low-level languages to comprehensive libraries in higher-level ones. In C, arrays provide a fundamental built-in mechanism for storing fixed-size sequences of elements of the same type in contiguous memory locations, while structs enable the grouping of heterogeneous variables into composite types.[72] These features form the core of data structure implementation in C, requiring programmers to handle memory management manually for more advanced needs.[72] Higher-level languages like Python offer more dynamic built-in data structures. Python's lists serve as mutable, ordered collections that support automatic resizing and heterogeneous elements, functioning as dynamic arrays under the hood.[65] Similarly, dictionaries provide unordered, mutable mappings of keys to values, implemented as hash tables with efficient lookups and dynamic growth.[65] This built-in flexibility reduces the need for explicit memory allocation in everyday programming tasks. Java provides robust support through its Collections Framework in the java.util package, which includes resizable ArrayList for dynamic arrays and HashSet for unordered collections without duplicates, both backed by efficient internal implementations like hash tables.[73][74] For sorted mappings, TreeMap implements a red-black tree-based structure, ensuring logarithmic-time operations for insertions and lookups while maintaining key order.[75] In C++, the Standard Template Library (STL) extends built-in support with container classes such as std::vector for dynamic arrays with automatic resizing, std::list for doubly-linked lists enabling efficient insertions and deletions, and std::map for sorted associative containers using balanced binary search trees. These templates allow generic programming, adapting to various data types without manual reimplementation. The availability of data structures often aligns with programming paradigms. Imperative languages like C emphasize manual construction of data structures using low-level primitives, prioritizing control over performance.[72] Object-oriented languages such as Java encapsulate data structures in classes within frameworks like Collections, promoting reusability and abstraction.[73] Functional languages, exemplified by Haskell, favor immutable data structures like lists, which are persistent and enable safe concurrent operations without side effects. Low-level languages like C exhibit gaps in support for advanced features, such as automatic dynamic resizing, necessitating manual implementation via functions like realloc for arrays or custom linked structures.[72] This approach demands careful handling to avoid memory leaks or fragmentation, contrasting with the automated mechanisms in higher-level languages.[65]Memory Allocation and Management

Memory allocation for data structures refers to the process of reserving space in a computer's memory to store the elements of these structures, which can occur either at compile time or during program execution. Static allocation assigns a fixed amount of memory at compile time, as seen in fixed-size arrays where the size is predetermined and cannot be altered runtime. This approach ensures predictable memory usage but lacks flexibility for varying data sizes. In contrast, dynamic allocation reserves memory at runtime, allowing structures like linked lists to grow or shrink as needed, typically using functions such asmalloc in C to request variable-sized blocks.[76][77]

Stack and heap represent the primary memory regions for allocation. Stack allocation, used for local variables and function calls, operates in a last-in, first-out manner with automatic deallocation upon scope exit, making it fast and suitable for fixed-size data structures like small arrays. Heap allocation, managed manually or automatically, supports larger, persistent data structures such as dynamic arrays or trees, but requires explicit handling to prevent resource waste.[78][79]

Management techniques vary by language and paradigm. In languages like C, manual deallocation via free after malloc is essential to reclaim heap memory and avoid leaks, where allocated space remains unusable after losing references. Automatic garbage collection, employed in Java and Python, periodically identifies and frees unreferenced objects; Java uses tracing algorithms like mark-and-sweep to detect unreachable memory, while Python primarily relies on reference counting augmented by cyclic detection. Dynamic allocation can lead to fragmentation, where free memory becomes scattered into small, non-contiguous blocks, reducing efficiency for large allocations—internal fragmentation wastes space within blocks, and external fragmentation hinders finding contiguous regions.[80][81][82][83][84]

Data structures exhibit distinct memory layouts. Arrays employ contiguous allocation, storing elements in sequential addresses, which enhances cache efficiency by enabling prefetching and reducing access latency on modern processors. Linked lists, however, use scattered allocation with each node containing data and pointers to adjacent nodes, incurring overhead from pointer storage—typically 4-8 bytes per node on 32/64-bit systems—leading to higher overall memory consumption compared to arrays for the same data volume.[85][86]

Key challenges in memory management include memory leaks and dangling pointers, particularly in manual systems like C. A memory leak occurs when allocated memory is not freed, gradually exhausting available resources; a dangling pointer references freed memory, potentially causing undefined behavior or crashes upon access. Best practices mitigate these through techniques like RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization) in C++, where smart pointers such as std::unique_ptr and std::shared_ptr automatically manage lifetimes, ensuring deallocation on scope exit and preventing leaks or dangling references without manual intervention.[87][88]