Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

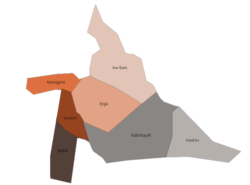

Fafan Zone

View on WikipediaFafan Zone (Somali: Gobolka Faafan) is a zone in Somali Region of Ethiopia. It was previously known as the Jijiga zone, so named after its largest city, Jijiga.[2] Other towns and cities in this zone include Awbare, Derwernache, Lefe Isa, Babile, Kebri Beyah, Harshin, Goljano, Tuli Gulled and Hart Sheik. Fafan is bordered on the south by Jarar, on the southwest by Nogob, on the west by the Oromia Region, on the north by Sitti, and on the east by Somaliland.

Key Information

Demographics

[edit]Based on the 2014 Census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), this Zone has a total population of 1,190,794 of whom 616,810 are men and 541,4794 women.[3]

Based on the 2007 Census 203,588 or 21.04% are urban inhabitants, a further 72,153 or 11.59% were pastoralists. Two largest ethnic groups reported in Jijiga were the Somalis (95.6%) and Amhara (1.83%); all other ethnic groups made up 2.57% of the population. Somali language is spoken as a first language by 95.51%, Amharic by 2.1%, and Oromo by 1.05%; the remaining 1.34% spoke all other primary languages reported. 96.86% of the population said they were Muslim, and 2.11% said they practiced Orthodox Christian.[4] There are three settlements in the zone for refugees from Somalia, with 40,060 registered individuals.[5]

The 1997 national census reported a total population for this Zone of 813,200 in 138,679 households, of whom 425,581 were men and 387,619 were women; 155,891 or 19.17% of its population were urban dwellers. The three largest ethnic groups reported in Fafan were the Somali (87.51%), the Oromo (7.49%), and the Amhara (2.13%); all other ethnic groups made up the remaining 2.87% of the population. Somali was spoken by 90.23% of the inhabitants, 6.68% Oromiffa, and 2.81% spoke Amharic; the remaining 0.28% spoke all other primary languages reported. Only 61,293 or 7.54% were literate.[6]

According to a May 24, 2004 World Bank memorandum, 7% of the inhabitants of Fafan have access to electricity, this Zone has a road density of 30.5 kilometers per 1000 square kilometers, the average rural household has 1.3 hectares of land (compared to the national average of 1.01 hectares of land and an average of 2.25 for pastoral regions)[7] and the equivalent of 1.0 head of livestock. 28.2% of the population is in non-farm related jobs, compared to the national average of 25% and a regional average of 28%. 21% of all eligible children are enrolled in primary school, and 9% in secondary schools. 74% of the zone is exposed to malaria, and none to Tsetse fly. The memorandum gave this zone a drought risk rating of 386.[8] In 2006, the Fafan Zone was affected by deforestation due to charcoal production.[9]

Districts

[edit]Based on the 2024 Census by the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia's Central Statistical Agency (CSA), Awbare district has the largest district population in the Somali Region.[10]

| District Name | Population (2024)[11] | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Awbare | 519,044 |

| 2. | Jijiga | 439,505 |

| 3. | Kebri Beyah | 254,251 |

| 4. | Harshin | 122,556 |

| 5. | Babile | 117,167 |

| 6. | Gursum | 42,082 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency Population of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014 Page: 21 Somali region". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

- ^ "Ethiopia" (PDF). USAID. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 21, 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ "Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency Population of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014 Page: 21 Somali region". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2017-01-19.

- ^ Census 2007 Tables: Somali Region Archived 2012-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, Tables 2.1, 2.4, 3.1, 3.2 and 3.4.

- ^ "Refugees in the Horn of Africa: Somali Displacement Crisis - Ethiopia - Jijiga". data.unhcr.org. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ 1994 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Results for Somali Region, Vol. 1 Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine Tables 2.1, 2.12, 2.13, 2.15 (accessed 12 January 2009). The results of the 1994 census in the Somali Region were not satisfactory, so the census was repeated in 1997.

- ^ Comparative national and regional figures comes from the World Bank publication, Klaus Deininger et al. "Tenure Security and Land Related Investment", WP-2991 Archived 2007-03-10 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 23 March 2006). This publication defines Benishangul-Gumaz, Afar and Somali as "pastoral Regions"

- ^ World Bank, Four Ethiopias: A Regional Characterization (accessed 23 March 2006).

- ^ CHF International, Grassroots Conflict Assessment in the Somali Region Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine (Aug. 2006), p. 19 (accessed 12 December 2008)

- ^ "Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency Population of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2024 Page: 17-18 Somali region". ess.gov.et. Retrieved 8 June 2025.

- ^ "Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency Population of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2024 Page: 17-18 Somali region". ess.gov.et. Retrieved 8 June 2025.