Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Failsworth

View on Wikipedia

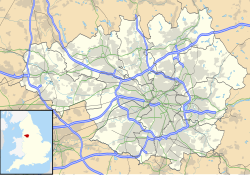

Failsworth (/ˈfeɪlzwɜːθ/) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, Greater Manchester, England,[1][2][3] 4 miles (6.4 km) north-east of Manchester and 3 miles (4.8 km) south-west of Oldham. The M60 ring-road motorway skirts it to the east. The population at the 2011 census was 20,680.[4][5] Historically in Lancashire, Failsworth until the 19th century was a farming township linked ecclesiastically with Manchester.[6] Inhabitants supplemented their farming income with domestic hand-loom weaving. The humid climate and abundant labour and coal led to weaving of textiles as a Lancashire Mill Town with redbrick cotton mills. A current landmark is the Failsworth Pole. Daisy Nook is a country park on the southern edge.

Key Information

Toponymy

[edit]Failsworth derives from the Old English fegels and worth, probably meaning an "enclosure with a special kind of fence".[7]

History

[edit]

Early settlement rested on a road that runs today between Manchester and Yorkshire. This Roman secondary road formed part of a network from Manchester up north, probably to Tadcaster near York.[8]: 5 The section that ran through Failsworth is still known as Roman Road. It was built above marshland and laid on brushwood with a hard surface. Roman Road has also been known as "Street", a Saxon term meaning "metalled road", indicating that it was also used that later period.[8]: 5

Early sources suggest the area was occupied in Saxon times.[8]: 5 The small hamlet of scattered dwellings made of rough local stone, mud and clay with thatched roofs, may have been stood on ground higher than the surrounding marshland. Daily life would have centred on animal husbandry and agriculture.[8]: 5

Unmentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, Failsworth appears in a record of 1212 as Fayleswrthe, a settlement was documented as a thegnage estate or manor comprising four oxgangs of land. Two oxgangs at an annual rate of 4 shillings were payable by the tenant, Gilbert de Notton, to Adam de Prestwich, who in turn paid tax to King John.[7][9] The other two oxgangs were held by the Lord of Manchester as part of his fee simple. The Byron family came to acquire the whole township in the mid-13th century. Apart from a small estate held by Cockersand Abbey, Failsworth passed to the Chetham family and was then sold on to smaller holders.[9]

By 1663, 50 households were registered.[8]: 6 Life centred on natural resources, agriculture and stock farming, with many were employed as labourers to work the land, though tradesmen such as a tailor, a felt maker, a shoemaker, a joiner and a weaver supported them. The earliest record of a place of worship is Dob Lane Chapel, dating from 1698.[8]: 6

In 1774, the 242 Failsworth households contained some 1.400 inhabitants,[8]: 6 of whom a high proportion were involved in cloth manufacture. Development of the English textile trade was backed by important legislation between 1500 and 1760: a number of acts were passed to encourage it by the compulsory growing of flax. Grants were made to flax growers and duties levied on foreign imports, though Manchester's extensive linen trade used yarn imported from Holland and Ireland.[8]: 6

In 1914 the regular Daisy Nook Easter Fair ceased with the outbreak of the First World War, but resumed in 1920. On 8 June 2007, a 1946 work by L. S. Lowry entitled "Good Friday, Daisy Nook" sold for £3,772,000, then the highest bid ever paid for one of his paintings.[10]

Timeline

[edit]- 1212 – First official record of Failsworth in King John's Great Inquest of Service[8]: 66 [11]

- 1212 – North-western portion of land held by the Lord of the Manor of Prestwick[8]: 66

- 1212 – South-eastern portion of land held by the Lords of the Manor of Manchester[8]: 66

- Mid-13th century – Richard and Robert de Byron acquired both portions of land[8]: 66

- 1320 – First record of a named place in Failsworth: Wrigley Head named in the Survey of the Manor of Manchester[8]: 66

- 1600–1699 – Population mostly working the land and supported by production of cloth[8]: 66

- 1660 – 43 names registered in the town[8]: 66

- 1663 – 50 recorded families[8]: 66

- 1673 – Earliest record of a place of worship: Dob Lane Chapel[8]: 66

- 1700–1799 – Most inhabitants involved in producing linen cloth, others farming[8]: 66

- 1735 – Manchester, Oldham and Austerlands Turnpike Trust improves the road between them.[8]: 66

- 1774 – 242 families recorded, with a population 1,400[8]: 66

- 1793 – The first Failsworth Pole erected[8]: 66

- 1796 – The earliest day school recorded is Pole Lane School.[8]: 66

- 1801 – Population 2,622[8]: 66

- 1803 – The main Turnpike Road is widened to 60 feet from Manchester to Dob Lane End.[8]: 66

- 1804 – Rochdale Canal opens on 21 December.[8]: 66

- 1825 – The first cotton mill built[8]: 66

- 1839 – The first mill built by Henry Walmsley[8]: 66

- 1844 – Failsworth constitutes a new parish: St John's.[8]: 66

- 1850 – A second Failsworth Pole erected[8]: 66

- 1851 – Population is 4,433[8]: 67

- 1859 – Failsworth Industrial Society is officially registered on 22 July.[8]: 67

- 1863 – The first Local Government Board is founded with nine members.[8]: 67

- 1878 – Horse-drawn trams are introduced between Manchester and Hollinwood.[8]: 67

- 1880 – A railway opens between Oldham and Manchester.[8]: 67

- 1881 – Failsworth acquires its first railway station in April.[8]: 67

- 1889 – A third Failsworth Pole erected[8]: 67

- 1894 – The Local Board is superseded by Failsworth Urban District Council.[8]: 67

- 1901 – Population 14,152[8]: 67

- 1901 – Electric trams replace the horse-drawn ones.[8]: 67

- 1903 – Merger with Manchester proposed[8]: 67

- 1904 – Merger with Manchester deferred[8]: 67

- 1924 – A fourth Failsworth Pole erected[8]: 67

- 1937 – The Roxy cinema presents its first feature on 20 December.[8]: 67

- 1946 – Failsworth Urban District Council proceeds with a housing clearance programme.[8]: 67

- 1946 – The last tram runs in Oldham.[8]: 67

- 1958 – The fifth and present Failsworth Pole erected[8]: 67

- 1973 – Failsworth is officially twinned with Landsberg am Lech in Germany.[8]: 67

- 1974 – Failsworth becomes part of the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham.[8]: 67

- 1991 – Population 20,999[8]: 67

- 1993 – The bicentenary of the first Failsworth Pole is marked.[8]: 67

- 2000 – The M60 motorway link opens.[8]: 67

Governance

[edit]

Lying within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire since the early 12th century, medieval Failsworth formed a township in the parish of Manchester and hundred of Salford.[3]

After the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, Failsworth joined the Manchester Poor Law Union, a social security unit.[3] Its first local authority was a local board of health set up in 1863 and responsible for standards of hygiene and sanitation.[3] The board constructed Failsworth Town Hall in 1880.[12] After the Local Government Act 1894, the area became Failsworth Urban District within the administrative county of Lancashire.[3] In 1933 came a small exchange of land with neighbouring Manchester; in 1954, parts of Limehurst Rural District were added to Failsworth Urban District.[3] Under the Local Government Act 1972, Failsworth Urban District was abolished. Since 1 April 1974 it has formed an unparished area of the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, a local government district within the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[3][13] Failsworth contains two of the twenty wards of the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham; Failsworth East and Failsworth West. The Failsworth Independent Party is active in the area and holds two of the seats on Oldham Council.

Failsworth lies in Manchester Central (UK Parliament constituency), represented in the House of Commons by Lucy Powell MP of the Labour Party.

Geography

[edit]At 53°30′37″N 2°9′27″W / 53.51028°N 2.15750°W (53.5102°, −2.1575°) Failsworth lies 163 miles (262 km) north-north-west of London, as the southern tip of the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham, sharing borders with Manchester (north to south-west) and Tameside (south to east). It is traversed by the A62 road between Manchester and Oldham, by the former rail line of the Oldham Loop and by the Rochdale Canal, across its north-west corner. The M60 motorway passes through. For the Office for National Statistics, Failsworth counts as part of the Greater Manchester Urban Area.[14]

The land in Failsworth slopes gently from east to west away from the Pennines and from brooks that bound it on the north-west (Moston Brook) and south-east (Lord's Brook). Failsworth has a country park, Daisy Nook, on undulating wooded land on its eastern border largely belonging to the National Trust. It is suited to walking, horse riding, fishing and other pursuits.

Demography

[edit]Population change

[edit]| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 14,152 | 15,998 | 16,973 | 15,726 | 17,505 | 18,032 | 19,819 | 20,951 | 20,160 | 20,007 |

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time[15][16][17] | ||||||||||

Economy

[edit]Failsworth grew as a mill town around the hat-making industry, which continues in the town. This began as a cottage industry before the firm of Failsworth Hats was set up in 1903 to manufacture silk hats. For a time the company had a factory near the former Failsworth Council offices and it remains in the area to this day.[18] Other activities include electrical goods manufacture (such as Russell Hobbs) by Spectrum Brands, formerly Pifco Ltd), and plastic production and distribution by Hubron Ltd.

In July 2007, the Tesco supermarket chain opened a 24-hour Extra branch superstore on the banks of the wharf. The move was opposed by shop-owners, who claimed they would have lost customers and may have been forced to close.[19][20][21][22] Tesco's arrival had been expected to be a catalyst bringing other stores, bars and restaurants to Failsworth.[23] The only other large store is a branch of Morrisons housed in a building constructed on the demolished site of Marlborough No. 2 Mill.

Landmarks

[edit]

A Failsworth Pole in Oldham Road was first raised in 1793 as a "political pole", although a local historian suggests there were others before and that maypoles probably stood there for centuries. It now stands on a site from which an earlier one blew down in 1950.

After a major restoration of the Pole, clock tower and gardens in 2006, a bronze statue of Benjamin Brierley was placed in the gardens.[24]

At the road junction of the A62 with Ashton Road West stands a cenotaph built in 1923 for over 200 Failsworth men who were killed in the First World War. Attendances at the cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday remain high at about 2,000.[25] The annual parade is led by 202 Field Squadron, RE (TA),[26] which is based in Failsworth. In June 2007 the war memorial was rededicated after a £136,000 makeover and opened by Colonel Sir John B. Timmins.

Education

[edit]The local comprehensive school is Co-op Academy Failsworth, which moved to a new building in 2008 from two buildings known as Upper School and Lower School. It caters for students aged between 11 and 16. The £28-million project brought the town's secondary schooling to come under one roof. It has specialist sports college status.[27][needs update]

| School | Type/Status | Headteacher | OfSTED | Location | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-op Academy Failsworth | Secondary School | Phillip Quirk | 105735 | 53°30′27″N 2°08′48″W / 53.507620°N 2.146614°W | [28] |

| Woodhouses VA Primary School | Primary School | Helen Woodward | 105688[permanent dead link] | 53°30′16″N 2°08′03″W / 53.504482°N 2.134096°W | [29] |

| South Failsworth Community Primary School | Primary School | Vicki Foy | 105656[permanent dead link] | 53°29′57″N 2°09′32″W / 53.499164°N 2.158921°W | [30] |

| Higher Failsworth Primary School | Primary School | Sam Forster | 134784[permanent dead link] | 53°30′51″N 2°08′55″W / 53.514258°N 2.148734°W | [31] |

| St John's CE Primary School | Primary School | Louise Bonter | 146670 | 53°30′32″N 2°09′03″W / 53.508982°N 2.150887°W | [32] |

| St Mary's RC Primary School | Primary School | Mary Garvey | 105727 | 53°30′17″N 2°09′36″W / 53.504745°N 2.159996°W | [33] |

| Mather Street Primary School | Primary School | Martine Buckley | 105649[permanent dead link] | 53°30′35″N 2°10′06″W / 53.509585°N 2.168270°W | [34] |

| Propps Hall Junior Infant and Nursery School | Primary School | Gillian Kay | 105663 | ||

| Spring Brook Academy (Upper School) | Special School | Sarah Dunsdon | 143472 | ||

| SMS Changing Lives School | Independent Special School | Hecabe DuFraisse | 146646 |

Religious sites

[edit]Transport

[edit]

Failsworth's main thoroughfare is Oldham Road (A62) between Manchester and Oldham. The M60 is an ring-road motorway circling Greater Manchester, with access via Junction 22. Its completion around 1995–2000 saw the installation of a graded junction and other notable changes to the A62. It led to several rows of buildings around the junction being demolished.

There are frequent buses through Failsworth between Manchester city centre and Oldham on Stagecoach Manchester's 83 Bee Network service. There is also a frequent service to Manchester city centre and to Saddleworth via Oldham, with service 84. Other bus destinations from Failsworth are Ashton-under-Lyne, Chadderton, Huddersfield, Rochdale, Royton, Saddleworth, Shaw & Crompton and Trafford Centre.

Failsworth tram stop in Hardman Lane is on the Oldham & Rochdale line of the Manchester Metrolink. At peak times, trams run every 6 minutes south towards East Didsbury via central Manchester and north to Shaw & Crompton or Rochdale via Oldham. At off-peak times, trams run every 12 minutes to East Didsbury and Rochdale.[46] Previously this was an unstaffed rail station on the Oldham Loop line serviced by Northern Rail services to Manchester Victoria or Rochdale via Oldham.[47] It closed in October 2009 under Phase 3a of Metrolink extension and re-opened as a tram stop in 2012.[48]

Twin town

[edit]Failsworth Urban District was twinned with Landsberg am Lech in Bavaria, Germany from 1974 to 2008.[49]

Notable people

[edit]

- Bonnie Prince Charlie (1720–1788), stayed overnight at the Bull's Head public house in 1745.[50]

- Sir Elkanah Armitage (1794–1876), a 19th-century industrialist, Liberal Party politician and former Lord Mayor of Manchester.[51][52]

- Benjamin Brierley (1825–1896), weaver, poet, essayist and writer in the Lancashire dialect. There is a bronze statue of him in the public gardens by The Pole.[53][54]

- Roy Fuller (1912–1991), an English writer, known mostly as a poet.

- Harry Boardman (1930–1987), the Lancashire folk singer was born locally

- Sir James Ratcliffe (born 1952), chemical engineer and businessman, chairman and CEO of the INEOS chemicals group, born locally.

- Darren Wharton (born 1961), singer and songwriter; member of Thin Lizzy, now fronts Dare

- Gary Mounfield (1962-2025), a musician known as Mani, formerly with the band the Stone Roses during the Madchester period and later joined Primal Scream.[55][56]

- Jim McMahon (born 1980), politician, MP has represented Oldham West, Chadderton and Royton since 2015, former leader of Oldham Council

- Agyness Deyn (born 1983), supermodel, real name Laura Michelle Hollins, brought up locally before her family moved to Ramsbottom.[57]

- Amy James-Kelly (born 1995), actress played Maddie Heath in Coronation Street grew up locally.[58]

Sport

[edit]- Mike Atherton (born 1968), broadcaster, journalist and former test cricketer, was brought up locally and played 115 Test cricket matches. Has a road, (Atherton Close), named after him, opposite the cricket club in Woodhouses where he played in his youth.[59][60][61]

- Ronnie Wallwork (born 1977), footballer, played 178 games, mainly for West Bromwich Albion, lived in Woodhouses

- Anthony Farnell (born 1978), Boxer, former WBU Middleweight champion known as the Woodhouse Warrior.[62][63] He has since become a fight trainer and owns a gym (Arnie's Gym) in nearby Newton Heath

- Katie Zelem (born 1996), footballer, has played over 180 games, including 115 for Manchester United W.F.C. and 12 for England

- Jamie Stott (born 1997), an English footballer who has played over 250 games

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cook, Hannah. "Failsworth Town Hall". www.oldham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Map Failsworth Town Centre Greater Manchester England". www.towncentremap.co.uk. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Greater Manchester Gazetteer". Greater Manchester County Record Office. Places names – D to F. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ "Oldham Ward/Failsworth West Ward population 2011". Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ "Oldham Ward/Failsworth East ward population 2011". Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ Lewis 1848, pp. 206–209.

- ^ a b Mills, A.D. (2003). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-852758-6. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Taylor, Sheila (2001). Failsworth Place and People. Oldham: Oldham Arts and Heritage Publications. ISBN 978-0-902809-98-7.

- ^ a b Brownbill & Farrer 1911, pp. 273–274.

- ^ "Lowry work fetches record £3.8m". BBC News. 8 June 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ Poole, Austin Lane (1993) [First published 1951]. From Domesday Book to Magna Carta, 1087-1216 (2nd revised ed.). Oxford, England: OUP Oxford. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-285287-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ayala, Beatriz (13 May 2009). "Hopes of new life for Failsworth Town Hall". Oldham Chronicle. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ HMSO. Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c. 70.

- ^ Office for National Statistics (2001). "Census 2001:Key Statistics for urban areas in the North; Map 3" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2007.

- ^ "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area". Government of the United Kingdom. 22 July 2004. KS01 Usual resident population

. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ "Greater Manchester Urban Area 1991 Census". National Statistics. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ 1981 Key Statistics for Urban Areas: The North Table 1. Office for National Statistics. 1981.

- ^ "Failsworth hats". Failsworth Hats. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ "Tesco's killing us say small traders". Oldham Advertiser. M.E.N. Media. 23 August 2007. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Conn, David (25 July 2007). "Supermarket sweep-up". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Richardson, Anne (12 November 2003). "Tesco target Failsworth". Oldham Advertiser. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Akbor, Ruhubia (6 February 2008). "Failsworth's £30m new look". Oldham Advertiser. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Conn, David (8 October 2008). "Buying into it". The Guardian. London.

- ^ J. McMahon and J. Crompton, The History of Failsworth Pole and the Ben Brierley Statue published June 2006.

- ^ Failsworth Local Matters (PDF). January 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ [1] Archived 25 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Failsworth School". School Finder. Ofsted. Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "Woodhouses Voluntary (Controlled) Primary School". School Finder. Ofsted. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "South Failsworth County Primary School". School Finder. Ofsted. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Higher Failsworth (Stansfield Road) Infants School". School Finder. Ofsted. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "St. John's C of E Junior School". School Finder. Ofsted. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "St. Mary's R.C. Primary School". School Finder. Ofsted. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ^ "Mather Street Primary School". School Finder. Ofsted. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Oldham Deanery – The Church of England Diocese of Manchester". Manchester.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ [2] Archived 12 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cooke, Fr. Michael; Fr. Francis Parkinson (2008). Salford Diocesan Almanac 2009. Salford: Gemini Print (Wigan). p. 232. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ "The Roman Catholic Parish of Holy Souls". Holysouls.freeserve.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Hope Methodist Church, Failsworth". Findachurch.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "romanroadchurch". Romanroadchurch.googlepages.com. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "New Life Church - Failsworth, Manchester". www.newlife-church.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "The Manchester District Association of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches". Unitarian.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ [3] Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Zion Old Baptist Union, Failsworth, Lancashire genealogy". GENUKI. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Failsworth". The Salvation Army. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Failsworth tram stop Transport for Greater Manchester

- ^ [4] Archived 6 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tony Williams LRTA Manchester Area Officer. "Manchester Metrolink – Oldham and Rochdale Line". Lrta.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Greer, Stuart (30 October 2007). "Twins separated". Oldham Advertiser. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to the award winning". Failsworth.info. Archived from the original on 19 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ John Moss (2005). "Politicians, Law & Social Reformers (10 of 12)". Manchester Politicians & the Northwest of England. Papillon (Manchester UK) Limited. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^ * Hampson, Charles Phillips (1930). Salford Through the Ages: The "Fons Et Origo" of an Industrial City. Manchester: E J Morton.

- ^ "Ben Brierley statue". John Cassidy. 14 June 2006. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Sutton, Charles William (1901). . Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). Vol. 1. pp. 269–270.

- ^ Taylor, Steve (2004) The A to X of Alternative Music, Continuum, ISBN 0-8264-7396-2

- ^ Madchester. AllMusic. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ Oliver, George (5 December 2007). "Tomboy Agyness is Britain's top model". Oldham Advertiser. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Turner, Matthew (6 March 2020). ""I'm a really proud Manc" – Military Wives actress Amy James-Kelly on growing up in Failsworth". I Love MCR. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ "Sports & Recreation". Buzzle.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Michael Andrew Atherton : Stats, Pics, Articles, Interviews and Milestones - Cricketfundas.com". www.cricketfundas.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ McHugh, Steve (24 July 2008). "Local cricket preview and fixtures". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Anthony Farnell – Boxer". Boxrec.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ "Latest Boxing News". BritishBoxing.net. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Brownbill, John; Farrer, William (1911). A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 5. Victoria County History. ISBN 978-0-7129-1055-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Lewis, Samuel (1848). A Topographical Dictionary of England. Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 978-0-8063-1508-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

External links

[edit] Media related to Failsworth at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Failsworth at Wikimedia Commons

Failsworth

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name Origin and Historical References

The name Failsworth derives from Old English fegels + worþ, in which worþ denotes an "enclosure" or "homestead," while fegels—a hypothetical derivative of the verb fegan ("to join, unite, or fix") with the suffix -isla—likely refers to a "bar" or "lock," suggesting an enclosed area secured by a specific fastening mechanism or type of barrier, such as a woven or joined fence.[8] This interpretation, proposed by philologist Eilert Ekwall in his analysis of Lancashire place names, aligns with the region's medieval agrarian features, where enclosures protected homesteads amid uncultivated terrain, though alternative derivations linking "fail" to a "clearing" have been suggested without consensus.[8] The place is unmentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 and first appears in records as Fayleswrthe in 1212, documented in the Lancashire Inquests and a related survey assessing feudal services under King John.[9] [8] Subsequent medieval spellings reflect phonetic evolution and scribal variation, including Faileswrthe (also 1212), Felesworde (1226 Lancashire Inquests), Failesworth (1246 Lancashire Assize Rolls), and Faylesworde (1451 charters).[8] These early references situate Failsworth within Manchester parish, east of Newton Heath between Moston Brook and the River Medlock, paralleling the -worþ element in nearby toponyms like those in Salford Hundred, which similarly denote enclosed settlements from Anglo-Saxon origins.[9] [8]History

Pre-Industrial Period

Failsworth originated as a medieval farming township within the historic county of Lancashire, first recorded as Failesworth around 1200.[9] In a 1212 survey, the area comprised four oxgangs of land divided into two moieties: two held by Adam de Prestwich under thegnage tenure at a rent of 4 shillings, and two by Robert Grelley on behalf of Robert de Byron under knight's service.[9] The Grelley family later acquired the Prestwich portion, consolidating ownership under the Byrons, whose tenure mirrored that of Clayton-le-Moors; by the 17th century, portions passed to smaller freeholders and the Chetham family.[9] The Abbey of Cockersand received a grant of land near Mossbrook from the Byrons around 1200, indicating early ecclesiastical involvement in local agrarian holdings.[9] Residents primarily engaged in agriculture, with common rights such as turbary on Droylsden Moor documented as late as 1615.[9] Ecclesiastically, Failsworth formed part of the ancient parish of Manchester, lacking its own dedicated church until the 19th century and relying on chapels for worship.[9] Nonconformist influences emerged early, exemplified by the erection of Dob Lane Chapel around 1698, which served Protestant dissenters amid the post-Restoration religious landscape.[9] Population remained modest, with hearth tax records from 1666 listing 69 houses, only one bearing four hearths liable for tax, reflecting a sparse rural settlement sustained by small-scale farming.[9] Land tax assessments in 1787 identified Mordecai Greene as the principal landowner, underscoring persistent agrarian dominance without significant expansion.[9] Supplementing farming incomes, inhabitants practiced domestic handloom weaving, particularly of silk, as a cottage industry leveraging the region's humid climate and available labor, though this remained ancillary to agriculture until later mechanization.[9] This pre-industrial economy exhibited limited growth, with no evidence of substantial demographic or economic shifts prior to the late 18th century, preserving Failsworth's character as a self-contained rural township.[9]Industrial Revolution and Growth

The advent of mechanized cotton production during the late 18th and early 19th centuries catalyzed Failsworth's transition from agrarian outpost to industrial hub, as water-powered mills along the River Medlock gave way to steam-driven facilities that amplified output and drew investment. This technological progression, rooted in innovations like Arkwright's water frame and Watt's steam engine, enabled the division of labor in spinning and weaving, yielding substantial productivity gains that outpaced pre-industrial handloom methods by factors of ten or more in yarn production. By the 1820s, Failsworth featured multiple such mills, contributing to the broader Lancashire cotton district's dominance, where raw cotton imports surged from 5 million pounds in 1790 to over 250 million by 1830, fueling local expansion.[10][11] Labor demand spurred rapid demographic shifts, with migrants—including Irish workers arriving en masse post-1845 Great Famine—filling mill roles amid England's industrial pull, as cotton employment offered wages double those in rural Ireland despite the era's volatility. Census data reflect this surge: Failsworth's populace, modest in the early 1800s, approached 14,000 by 1901, underscoring the causal link between mill proliferation and urbanization, though haphazard housing strained sanitation and health. Irish settlers, comprising a notable fraction of Manchester-area mill hands, integrated into Failsworth's workforce, their numbers bolstered by canal and rail links facilitating raw material and labor flows.[9][12] Mill operations imposed grueling conditions, with operatives enduring 12- to 16-hour shifts in humid, dust-laden environments prone to machinery accidents, while child labor persisted until reforms like the 1833 Factory Act prohibited employment under age nine and capped hours for minors—measures prompted by parliamentary inquiries revealing stunted growth and deformities among young workers. Yet these factories instantiated causal efficiencies: specialized tasks reduced skill barriers, elevating output per worker and generating surplus value that funded infrastructure, even as exploitation spurred resistance. Early collective responses materialized in the 1859 founding of the Failsworth Industrial Society, a worker cooperative providing fairer retail and credit amid wage pressures, prefiguring broader unionism in Lancashire's cotton trades.[13]Post-Industrial Decline and Regeneration

Following the peak of the textile industry in the early 1950s, Failsworth experienced significant deindustrialization as cotton mills closed amid intensifying global competition from low-wage producers in Asia and the rise of synthetic fibers, which eroded demand for traditional cotton goods. A 1954 parliamentary debate highlighted the closure of a major spinning mill in nearby Oldham, reflecting broader pressures on Lancashire's textile sector where mills shuttered at rates approaching one per week by the late 1950s and 1960s.[14][15] This led to sharp unemployment increases; while national rates hovered around 2% in the 1950s-1960s, local industrial towns like those in Greater Manchester saw spikes, with Oldham borough—encompassing Failsworth—reporting rates exceeding 5-6% by the early 1970s amid structural job losses estimated at over 2.5 million in UK manufacturing between the mid-1960s and late 1970s cycles.[16][17] The economic contraction prompted a pivot toward commuter suburb status, leveraging Failsworth's proximity to Manchester's expanding service and administrative sectors, with improved road links facilitating daily workforce outflows. Post-war housing initiatives, including 1960s clearances of terraced mill-worker homes and re-housing into modern estates, supported population retention despite job scarcity, though these developments prioritized physical upgrading over industrial revival.[18][19] Government responses in the 1970s, such as the Urban Programme launched in 1968 and the Inner Urban Areas Act of 1978, funded localized renewal in Manchester's periphery, including infrastructure and housing rehabilitation in Oldham districts like Failsworth, aiming to mitigate dereliction from mill vacancies. However, these top-down interventions showed limited efficacy in causal terms for employment recovery, as physical redevelopment failed to generate sustainable local jobs—evidenced by persistent unemployment above national averages into the late 1970s, with structural deindustrialization outweighing scheme outputs in metrics like job creation and wage stability.[20][21][22]Recent Developments (Post-2000)

In 2019, Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council approved a £35 million redevelopment at Hollinwood Junction in Failsworth, encompassing 15.5 acres of former industrial land off Roman Road, including new employment spaces, up to 150 family homes, community facilities, and leisure areas projected to generate 760 jobs and establish a regional business hub.[23][24] This initiative included essential infrastructure upgrades, such as a new access road and roundabout adjacent to the M60 motorway, enhancing connectivity and supporting measurable improvements in local employment access.[24] Addressing persistent deprivation—where Failsworth West lower super output areas recorded 22.5% income deprivation and 22.5% employment deprivation in the 2019 Indices of Deprivation, contributing to Oldham's ranking as the 19th most deprived local authority in England—council-led green infrastructure projects emerged post-2020.[25][26] In 2023, Oldham Council allocated £1.35 million to the Wrigley Head Solar Farm on a reclaimed industrial landfill site alongside the Metrolink line, anticipated to cut annual CO2 emissions by 50 tonnes and reduce community energy costs through renewable generation.[27][28] By 2025, smaller-scale housing regeneration addressed affordability gaps, with a £3.7 million brownfield project delivering 14 energy-efficient homes on Hardman Street via shared ownership and affordable rent schemes targeted at first-time buyers.[29] Complementary sustainable transport enhancements included a £4 million electric vehicle charging hub with 12 ultra-rapid bays, aligning with broader Levelling Up green technology funding to mitigate economic stagnation exacerbated by COVID-19 disruptions to local supply chains and retail.[30] These efforts yielded tangible outcomes, such as improved green space access and reduced reliance on fossil fuels, though borough-wide data indicate ongoing challenges in reversing post-pandemic business closures averaging 9.7% GDP contraction in affected sectors.[31]Governance

Local Administration

Prior to 1974, Failsworth was administered by the Failsworth Urban District Council, which replaced a local board established in 1863 and operated from 1894 until its abolition.[9] The council, comprising twelve members, managed township affairs and divided the area into two wards for representation.[9] Archival records indicate routine local governance functions, though specific boundary disputes from this era remain undocumented in accessible public sources. The Local Government Act 1972 reorganized administrative structures, abolishing the Failsworth Urban District on 1 April 1974 and integrating it as an unparished area into the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham.[10] Failsworth now forms the Failsworth East and Failsworth West wards within Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council, which serves as the primary local authority responsible for boundary maintenance and service delivery.[32] Oldham Council delivers essential services to Failsworth residents, including waste management through weekly collections for households and businesses, and planning functions via development control and policy implementation.[33] Waste disposal incurs costs of £290 per tonne, prompting council initiatives for reduction and recycling enhancements across wards to improve fiscal efficiency.[34] In recent ward boundary reviews, local councillors advocated preserving Failsworth's unified identity to align administrative divisions with community cohesion.[35]Political Dynamics and Representation

Failsworth's wards, East and West, have been represented on Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council since 1974, with the Labour Party maintaining dominance reflective of the area's industrial working-class base and post-war electoral trends from 1945 onward, where Labour secured consistent majorities in local contests.[36] Conservative challenges peaked sporadically, such as in the 1960s and 1970s amid national shifts, but Labour retained control in Failsworth East with candidates often exceeding 50% vote shares in elections like 2019 and earlier cycles.[37] In Failsworth West, Labour holds were similarly firm until recent decades, with turnout and results underscoring loyalty tied to trade union influences and economic policies favoring public sector expansion.[38] Shifts emerged prominently in the 2021 local elections, where Labour lost ground in Failsworth West, including the defeat of council leader Sean Fielding by an independent candidate, signaling voter frustration with service delivery and rising immigration-related pressures straining resources in the borough.[39] Official tallies showed independents and others capitalizing on turnout of around 30-35%, with concerns over community cohesion and public services—exacerbated by demographic changes—driving support away from Labour, as articulated in local analyses of Oldham-wide discontent.[40] This pattern continued into 2024, when an independent, Mark Jeffrey Wilkinson, won Failsworth West by a 14% margin (1,159 votes to Labour's 1,145), contributing to Labour's loss of overall council control amid broader independent gains.[41] Failsworth East remained Labour-leaning but with narrowing margins, highlighting fragmented representation favoring localized appeals over party loyalty.[42] Criticisms of representation effectiveness center on perceived erosion of local autonomy following the 1974 merger into Oldham Council, where centralized metropolitan decisions have overridden Failsworth-specific priorities, such as infrastructure tailored to its semi-rural edges, leading some residents to favor independents for more responsive advocacy.[43] Proponents of Labour's record counter that it delivered substantive achievements, including extensive council housing programs in the mid-20th century that housed thousands amid industrial decline, though detractors argue recent failures in addressing integration challenges and service strains have undermined trust.[44] Independent and Reform UK gains, including 2025 defections from Oldham councillors, reflect ongoing debates over whether entrenched Labour representation prioritizes national ideology over empirical local needs like controlling immigration impacts on housing and policing.[45]Geography

Location and Physical Features

Failsworth occupies a position approximately 4 miles (6 kilometers) northeast of Manchester city centre, within the Metropolitan Borough of Oldham in Greater Manchester, England.[46] This placement situates it on the periphery of the Manchester conurbation, contributing to its role as an urban extension amid transitioning landscapes.[47] The town's topography features gently sloping terrain from east to west, descending away from the Pennine hills that form the regional backdrop to the northeast.[10] Natural watercourses, including the Ashton Canal that passes through the area and the adjacent River Medlock, have historically shaped drainage patterns and land use, with the Medlock's upper reaches influencing valley configurations near Failsworth.[48][49] These elements define a landscape of moderate elevation, typically ranging from 100 to 150 meters above sea level, bounded by brooks such as Moston Brook to the northwest. As an urban-rural fringe location, Failsworth is encircled by green belt designations established under the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, aimed at curbing urban expansion and preserving open spaces around major settlements.[50] Greater Manchester's green belt framework, including areas adjacent to Failsworth, enforces strict development controls to maintain countryside separation and prevent coalescence with neighboring towns.[51]Environmental and Urban Characteristics

Failsworth's urban landscape reflects dense residential development, with a mix of Victorian terraced housing from its textile era and post-war council estates that expanded the town's footprint in the mid-20th century. These estates, constructed to address post-World War II housing shortages, feature low-rise blocks and semi-detached properties, contributing to a high population density of approximately 3,500 residents per square kilometer in core wards like Failsworth East and West, which strains local infrastructure such as roads and utilities but supports walkable community access to amenities. Ongoing brownfield redevelopments, prioritizing former industrial sites, have added over 50 new housing units since 2023, including 14 affordable homes on Hardman Street and 18 at Hughes Close, fostering efficient land use and reducing dereliction without expanding into green belt areas.[52][53][54] Air quality in Failsworth is moderately compromised by its adjacency to the M60 motorway, a major orbital route carrying high volumes of diesel traffic that elevates nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations. Portions of the town fall within Oldham Metropolitan Borough's Air Quality Management Area, declared on 1 June 2001 to address NO2 exceedances from road sources, with historical roadside measurements in Greater Manchester averaging 40-50 µg/m³ annually near similar motorways, correlating with increased respiratory health risks for residents in proximity. Current monitoring via regional networks shows daily indices often in the "low" to "moderate" range (AQI 1-3), attributable to cleaner vehicle technologies, though persistent traffic volumes maintain causal pressure on livability through reduced outdoor activity feasibility during peaks.[55][56] Flood risks stem primarily from the Hollinwood Branch Canal and Moston Brook, which channel surface water and fluvial flows through low-lying urban zones, historically leading to localized inundation during intense rainfall. Post-2007 UK-wide flood reviews prompted regional investments in defenses, including culvert upgrades and maintenance under the Greater Manchester Strategic Flood Risk Management Framework, yielding empirically lower incident rates with no major Failsworth events recorded since, as evidenced by Environment Agency assessments classifying most postcodes (e.g., M35) at "very low" long-term risk from rivers and surface water. These measures enhance resilience by attenuating peak flows, directly improving property protection and reducing disruption costs, though unmaintained private culverts remain a vulnerability in denser estates.[57][58][59]Demographics

Population Trends

The population of Failsworth grew substantially during the 19th century amid industrialization, rising from 4,433 in 1851 to 14,152 by 1901.[60][9] This expansion reflected the influx of workers to cotton mills and related manufactories in the township.[60]| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1851 | 4,433 |

| 1901 | 14,152 |

| 2011 | 20,680 |

| 2021 | 19,960 |