Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Subsidiarity

View on Wikipedia

Subsidiarity is a principle of social organization that holds that social and political issues should be dealt with at the most immediate or local level that is consistent with their resolution. The Oxford English Dictionary defines subsidiarity as "the principle that a central authority should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks which cannot be performed at a more local level".[1] The concept is applicable in the fields of government, political science, neuropsychology, cybernetics, management and in military command (mission command). The OED adds that the term "subsidiarity" in English follows the early German usage of "Subsidiarität".[2] More distantly, it is derived from the Latin verb subsidio (to aid or help), and the related noun subsidium (aid or assistance).

The development of the concept of subsidiarity has roots in the natural law philosophy of Thomas Aquinas and was mediated by the social scientific theories of Luigi Taparelli, SJ, in his 1840–43 natural law treatise on the human person in society.[3] In that work, Taparelli established the criteria of just social order, which he referred to as "hypotactical right" and which came to be termed "subsidiarity" following German influences.[4]

Another origin of the concept is in the writings of Calvinist law-philosopher Johannes Althaus who used the word "subsidia" in 1603.[5][6] As a principle of just social order, it became one of the pillars of modern Catholic social teaching.[3][7] Subsidiarity is a general principle of European Union law. In the United States of America, Article VI, Paragraph 2 of the constitution of the United States is known as the Supremacy Clause. This establishes that the federal constitution, and federal law generally, take precedence over state laws, and even state constitutions.[8] The principle of states' rights is sometimes interpreted as being established by the Tenth Amendment, which says that "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."

Political theory

[edit]Alexis de Tocqueville's classic study, Democracy in America, may be viewed as an examination of the operation of the principle of subsidiarity in early 19th century America. Tocqueville noted that the French Revolution began with "a push towards decentralization… in the end, an extension of centralization".[9] He wrote that "Decentralization has, not only an administrative value, but also a civic dimension, since it increases the opportunities for citizens to take interest in public affairs; it makes them get accustomed to using freedom. And from the accumulation of these local, active, persnickety freedoms, is born the most efficient counterweight against the claims of the central government, even if it were supported by an impersonal, collective will."[10]

| Part of a series on |

| Christian democracy |

|---|

|

As Christian Democratic political parties were formed, they adopted the Catholic social teaching of subsidiarity, as well as the neo-Calvinist theological teaching of sphere sovereignty, with both Catholics and Protestants agreeing "that the principles of sphere sovereignty and subsidiarity boiled down to the same thing".[11]

The term "subsidiarity" is also used to refer to a tenet of some forms of conservative or libertarian thought in the United States. For example, conservative author Reid Buckley writes:

Will the American people never learn that, as a principle, to expect swift response and efficiency from government is fatuous? Will we never heed the principle of subsidiarity (in which our fathers were bred), namely that no public agency should do what a private agency can do better, and that no higher-level public agency should attempt to do what a lower-level agency can do better – that to the degree the principle of subsidiarity is violated, first local government, the state government, and then federal government wax in inefficiency? Moreover, the more powers that are invested in government, and the more powers that are wielded by government, the less well does government discharge its primary responsibilities, which are (1) defence of the commonwealth, (2) protection of the rights of citizens, and (3) support of just order.[12]

The United Nations Development Programme's 1999 report on decentralisation noted that subsidiarity was an important principle. It quoted one definition:

Decentralization, or decentralising governance, refers to the restructuring or reorganisation of authority so that there is a system of co-responsibility between institutions of governance at the central, regional and local levels according to the principle of subsidiarity, thus increasing the overall quality and effectiveness of the system of governance, while increasing the authority and capacities of sub-national levels.[13]

According to Richard Macrory, the positive effects of a political/economic system governed by the principle of subsidiarity include:[14]

- Systemic failures of the type seen in the crash of 2007/08 can largely be avoided, since diverse solutions to common problems avoid common mode failure.

- Individual and group initiative is given maximum scope to solve problems.

- The systemic problem of moral hazard is largely avoided. In particular, the vexing problem of atrophied local initiative/responsibility is avoided.

He writes that the negative effects of a political/economic system governed by the principle of subsidiarity include:

- When a genuine principle of liberty is recognised by a higher political entity but not all subsidiary entities, implementation of that principle can be delayed at the more local level.

- When a genuinely efficacious economic principle is recognised by a higher political entity, but not all subsidiary entities, implementation of that principle can be delayed at the more local level.

- In areas where the local use of common resources has a broad regional, or even global, impact, higher levels of authority may have a natural mandate to supersede local authority.[14]

General principle of European Union law

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

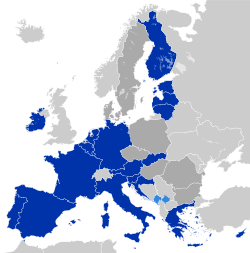

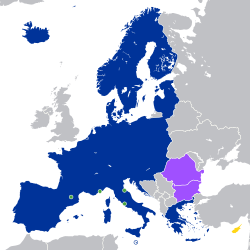

Subsidiarity is perhaps presently best known as a general principle of European Union law. According to this principle, the Union may only act (i.e. make laws) collectively where independent action of individual countries is insufficient without equal action by other members. The principle was established in the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht.[15] However, at the local level it was already a key element of the European Charter of Local Self-Government, an instrument of the Council of Europe promulgated in 1985 (see Article 4, Paragraph 3 of the Charter) (which states that the exercise of public responsibilities should be decentralised). Subsidiarity is related in essence to, but should not be confused with, the concept of a margin of appreciation.

Subsidiarity was established in EU law by the Treaty of Maastricht, which was signed on 7 February 1992 and entered into force on 1 November 1993. The present formulation is contained in Article 5(3) of the Treaty on European Union (consolidated version following the Treaty of Lisbon, which entered into force on 1 December 2009):

Under the principle of subsidiarity, in areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Union shall act only if and in so far as the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States, either at central level or at regional and local level, but can rather, by reason of the scale or effects of the proposed action, be better achieved at Union level.

The national parliaments of EU member states have an "early warning mechanism" whereby if one third raise an objection – a "yellow card" – on the basis that the principle of subsidiarity has been violated, then the proposal must be reviewed. If a majority do so – an "orange card" – then the council or parliament can vote it down immediately. If the logistical problems of putting this into practice are overcome, then the power of the national parliaments could be deemed an extra legislature, without a common debate or physical location: dubbed by EUObserver a "virtual third chamber".[16]

A more descriptive analysis of the principle can be found in Protocol 2 to the European Treaties.[17]

Court of Justice

[edit]The Court of Justice of the European Union in Luxembourg is the authority that has to decide whether a regulation falls within the exclusive competence[a] of the Union, as defined by the Treaty on European Union and its predecessors. As the concept of subsidiarity has a political as well as a legal dimension, the Court of Justice has a reserved attitude toward judging whether EU legislation is consistent with the concept. The Court will examine only marginally whether the principle is fulfilled. A detailed explanation of the legislation is not required; it is enough that the EU institutions explain why national legislation seems inadequate and that Union law has an added value.

An example is the judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union in a legal action taken by the Federal Republic of Germany against the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union concerning a Directive on deposit guarantee schemes (13 May 1997). Germany argued that the Directive did not explain how it was compatible with the principle of subsidiarity. The Court answered:

In the present case, the Parliament and the Council stated in the second recital in the preamble to the Directive that "consideration should be given to the situation which might arise if deposits in a credit institution that has branches in other Member States became unavailable" and that it was "indispensable to ensure a harmonised minimum level of deposit protection wherever deposits are located in the Community". This shows that, in the Community legislature's view, the aim of its action could, because of the dimensions of the intended action, be best achieved at Community level....

Furthermore, in the fifth recital the Parliament and the Council stated that the action taken by the Member States in response to the Commission's Recommendation has not fully achieved the desired result. The Community legislature therefore found that the objective of its action could not be achieved sufficiently by the Member States.

Consequently, it is apparent that, on any view, the Parliament and the Council did explain why they considered that their action was in conformity with the principle of subsidiarity and, accordingly, that they complied with the obligation to give reasons as required under Article 190 of the Treaty. An express reference to that principle cannot be required.

On those grounds, the plea of infringement of the obligation to state reasons is unfounded in fact and must therefore be rejected. (Case C-233/94[18])

See also

[edit]- Anti-Federalists – 1780s political movement in the US

- Cellular democracy – Subsidiary democratic model

- Decentralization – Organizational theory

- Devolution – Granting of some competences of central government to local government

- Distributism – Economic theory promoting local control

- Federalism – Political concept

- Grassroots democracy – Type that favors individual activism

- Local government – Lowest in the administration pyramid

- Localism (politics) – Political philosophy

- Margin of appreciation – Doctrine in international human rights law

- Parochialism – Focus on small sections of an issue

- Primary and secondary legislation – Two forms of law in democracies

- Principle of conferral – EU acts at the behest of its members

- Public choice – Economic theory applied to political science

- Oswald von Nell-Breuning – German Catholic theologian

- Staatenverbund – Potent union of sovereign states

- Urban secession – City becomes independent political unit

Notes

[edit]- ^ Exclusive competencies are those matters that the member states have agreed with each other by treaty are those that they should achieve jointly (typically through the European Commission). All other matters remain as "national competences" (each member decides its own policy independently). International trade agreements are an example of the former, taxation is an example of the latter.

References

[edit]- ^ "subsidiarity". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019.

[mass noun] (in politics) the principle that a central authority should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks which cannot be performed at a more local level

- ^ Early German usage: Subsidiarität (1809 or earlier in legal use; 1931 in the context of Catholic social doctrine, in §80 of Rundschreiben über die gesellschaftliche Ordnung ("Encyclical concerning the societal order"), the German version of Pope Pius XI's encyclical Quadragesimo anno (1931))".

- ^ a b Behr, Thomas. Social Justice and Subsidiarity: Luigi Taparelli and the Origins of Modern Catholic Social Thought (Washington DC: Catholic University of American Press, December 2019).

- ^ Behr, Thomas. Social Justice and Subsidiarity: Luigi Taparelli and the Origins of Modern Catholic Social Thought (Washington DC: Catholic University of American Press, December 2019). See in particular the Appendix, Taparelli's "Treatise on Subsidiarity" translated in this work.

- ^ Endo, Ken (31 May 1994). "The Principle of Subsidiarity: From Johannes Althusius to Jacques Delors". 北大法学論集. 44 (6): 652-553.

It is reasonable however to also identify Althusius as the first proponent of subsidiarity and federalism (he uses, in fact, the word "subsidia" in the text). He was a Calvinist theoretician of the laical State at the beginning of the 17th century.

- ^ Frederik H. Kistenkas (1 January 2000). "European and domestic subsidiarity. An Althusian conceptionalist view". Tilburg Law Review. 8 (3): 247–254. doi:10.1163/221125900X00044. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Das Subsidiaritätsprinzip als wirtschaftliches Ordnungsprinzip", Wirtschaftliche Entwicklung und soziale Ordnung. Degenfeld-Festschrift, Vienna: von Lagler and J. Messner, 1952, pp. 81–92, cited in Helmut Zenz, DE, archived from the original on 31 October 2007, retrieved 9 November 2009.

- ^ "Supremacy Clause". LII. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Schmidt, Vivien A (23 March 2007), Democratizing France: The Political and Administrative History of Decentralization, Cambridge University Press, p. 10, ISBN 978-0-52103605-4.

- ^ A History of Decentralization Archived 11 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Earth Institute of Columbia University, retrieved 4 February 2013

- ^ Segell, Glen (2000). Is There a Third Way?. Glen Segell Publishers. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-90141418-9.

When the Dutch Protestant and Catholic parties combined, to form the Christian Democrats, the two parties agreed that the principles of sphere sovereignty and subsidiarity boiled down to the same thing.

- ^ Reid Buckley, An American Family – The Buckleys, Simon & Schuster, 2008, p. 177.

- ^ Decentralization: A Sampling of Definitions Archived 12 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Joint UNDP (United Nations Development Programme)-Government of Germany evaluation of the UNDP role in decentralization and local governance, the United Nations Development Programme, October 1999, pp. 2, 16, 26.

- ^ a b Macrory, Richard, 2008, Regulation, Enforcement and Governance in Environmental Law, Cameron May, London, p. 657.

- ^ Shelton, Dinah (2003). "The Boundaries of Human Rights Jurisdiction in Europe". Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law. 13 (1). Duke University School of Law: 95–154. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Cooper, Ian (16 October 2009) Comment: Will national parliaments use their new powers? Archived 25 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, EUObserver

- ^ Protocol 2 to the European Treaties Archived 6 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Judgment Of The Court in Case C-233/94". Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

External links

[edit]- Treaty establishing the European Community

- The Assembly of European Regions' Subsidiarity is a word movement, demanding recognition in dictionaries worldwide

- "Subsidiaritaet" in the Lexikon der sozialoekologischen Marktwirtschaft