Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Core (optical fiber)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

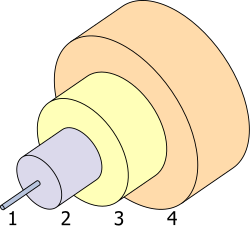

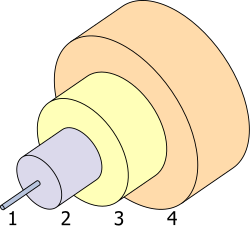

1. Core 9 μm diameter

2. Cladding 125 μm dia.

3. Coating 250 μm dia.

4. Buffer or jacket 900 μm dia.

The core of a conventional optical fiber is the part of the fiber that guides the light. It is a cylinder of glass or plastic that runs along the fiber's length.[1] The core is surrounded by a medium with a lower index of refraction, typically a cladding of a different glass, or plastic. Light travelling in the core reflects from the core-cladding boundary due to total internal reflection, as long as the angle between the light and the boundary is greater than the critical angle. As a result, the fiber transmits all rays that enter the fiber with a sufficiently small angle to the fiber's axis. The limiting angle is called the acceptance angle, and the rays that are confined by the core/cladding boundary are called guided rays.

The core is characterized by its diameter or cross-sectional area. In most cases the core's cross-section should be circular, but the diameter is more rigorously defined as the average of the diameters of the smallest circle that can be circumscribed about the core-cladding boundary, and the largest circle that can be inscribed within the core-cladding boundary. This allows for deviations from circularity due to manufacturing variation.

Another commonly quoted statistic for core size is the mode field diameter. This is the diameter at which the intensity of light in the fiber falls to some specified fraction of maximum (usually 1/e2 ≈ 13.5%). For single-mode fiber, the mode field diameter is larger than the physical diameter of the core, because the light penetrates slightly into the cladding as an evanescent wave.

The three most common core sizes are:

- 9 μm diameter (single-mode)

- 50 μm diameter (multi-mode)

- 62.5 μm diameter (multi-mode)[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Insulation/circuits. Lake Publishing Corporation. 1978.

- ^ "The FOA Reference For Fiber Optics - Optical Fiber". www.thefoa.org. Retrieved April 10, 2016.

Core (optical fiber)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

The core is the innermost cylindrical region of an optical fiber, serving as the primary conduit for light propagation through total internal reflection at its boundary with the surrounding cladding.[3][1] This central structure is engineered to carry optical signals with minimal loss, distinguishing it from the outer cladding and protective coating layers that provide mechanical support and environmental isolation.[4] Typically composed of high-purity glass or plastic materials, the core functions as the light-transmitting medium, where photons are confined and directed along the fiber's axis.[1] Its diameter varies significantly by fiber type, ranging from approximately 8–10 micrometers in single-mode fibers for long-distance telecommunications to 50–1000 micrometers in multimode or plastic optical fibers for shorter-range applications.[1][4] The terminology "core" for the central light-guiding region was formalized in Elias Snitzer's 1961 paper "Cylindrical Dielectric Waveguide Modes," which described a cylindrical dielectric waveguide consisting of a core of higher refractive index surrounded by cladding to enable total internal reflection.[5] This concept was advanced in the seminal 1966 paper by Charles K. Kao and George A. Hockham, which proposed using such cladded structures for low-loss optical communication.[6] This foundational work laid the groundwork for modern optical fiber design by emphasizing the core's role in achieving low-attenuation signal transmission.Role in Light Propagation

In optical fibers, light enters the core, which serves as the primary conduit for signal transmission, and is confined within it through the principle of total internal reflection at the core-cladding interface. This confinement occurs because the core possesses a higher refractive index than the surrounding cladding, ensuring that light rays incident on the interface at angles greater than the critical angle are reflected back into the core rather than refracting out.[7] The small difference in refractive indices between the core and cladding enables this guiding mechanism, allowing light to propagate over long distances with minimal loss to the exterior.[7] The core supports various propagation modes that determine how light travels along the fiber. Meridional rays, which pass through the fiber axis and reflect in a plane containing the axis, travel straight along the core's length, repeatedly crossing the center and producing high optical intensity there.[8] In contrast, skew rays do not intersect the axis but instead follow a helical path, spiraling around it and reflecting off the core-cladding boundary at an angle, which results in lower central intensity but allows for a broader acceptance of light input.[9] These modes collectively enable the core to guide multiple light paths, essential for multimode fibers carrying higher data capacities.[8] Total internal reflection is governed by the critical angle, defined as the incident angle at which light refracts at 90° into the cladding, beyond which all light reflects internally. This angle arises from Snell's law, which states that for light traveling from the core (refractive index ) to the cladding (refractive index , where ), . At the critical angle , the refracted angle , so , yielding . Solving for gives , or .[10] Rays with incidence angles greater than thus remain trapped in the core, forming the basis of guided propagation.[10] While the core facilitates efficient light guidance, it is also the primary source of signal degradation through attenuation and dispersion. Attenuation stems mainly from absorption by impurities or intrinsic material properties in the core and Rayleigh scattering due to density fluctuations within it, reducing signal intensity over distance.[2] Dispersion, particularly modal dispersion in multimode fibers, arises from varying path lengths and group velocities of modes within the core, causing pulse broadening and limiting transmission distance and bandwidth.[2] These effects underscore the core's central role in maintaining signal integrity during propagation.[2]Materials and Composition

Primary Materials

The core of optical fibers is predominantly constructed from ultra-pure fused silica (SiO₂), valued for its exceptional optical transparency in the near-infrared spectrum and minimal light attenuation, typically below 0.2 dB/km at 1550 nm, which arises primarily from Rayleigh scattering and intrinsic material absorption.[1][11] This material's high purity, achieved through processes like modified chemical vapor deposition, ensures low defect densities and enables reliable light transmission over extended distances. Fused silica also offers mechanical robustness, with a high melting point exceeding 1700°C, making it suitable for the high-temperature drawing processes used in fiber manufacturing.[12] For short-distance applications, such as local area networks or consumer electronics, plastic cores made from polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) provide a cost-effective and flexible alternative to glass, though they exhibit significantly higher attenuation, ranging from 100 to 1000 dB/km in the visible to near-infrared range, limiting their use to spans under 100 meters.[13][14] PMMA's ease of extrusion and lower production costs make it ideal for multimode fibers in environments requiring bend resistance, but its performance degrades due to higher intrinsic absorption from C-H bonds.[15] Alternative glass compositions, such as phosphate glasses, are employed in specialized cores to improve solubility for dopants, supporting applications in high-power lasers where silica's limitations in rare-earth ion incorporation are a concern. Chalcogenide glasses, exemplified by arsenic trisulfide (As₂S₃), serve as core materials for mid-infrared transmission, offering broad transparency up to 10 μm with low losses in the 1.5–6.5 μm range, ideal for sensing and spectroscopy in wavelengths beyond silica's capabilities.[17][18] The foundational role of silica cores in enabling long-haul transmission was demonstrated in the early 1970s by researchers at Corning Glass Works, who achieved losses under 20 dB/km, enabling practical light transmission over kilometer-scale distances and paving the way for modern telecommunications networks.[19]Doping Techniques

Doping with germanium dioxide (GeO₂) is a primary technique to elevate the refractive index of the silica core in optical fibers, enabling effective light confinement essential for single-mode propagation. This dopant integrates into the silica matrix, typically increasing the refractive index by approximately 0.01 to 0.03 relative to undoped silica, depending on concentration and processing conditions. GeO₂ doping is widely employed in standard silica-based cores due to its compatibility with vapor deposition methods and minimal impact on optical losses at telecommunication wavelengths. In contrast, fluorine (F) doping serves to lower the refractive index, particularly for creating specialized low-index cores or claddings in dispersion-managed fibers. By incorporating fluorine atoms, typically up to 1-2 mol%, the index can be reduced by 0.005 to 0.01, which helps minimize chromatic dispersion in certain fiber designs while maintaining low attenuation.[20] This approach is valuable for applications requiring precise control over waveguiding properties without introducing absorption bands. Other dopants play supportive roles in core modification. Phosphorus pentoxide (P₂O₅) is added to adjust glass viscosity during manufacturing, facilitating uniform deposition and reducing crystallization risks, often at levels of 1-5 mol% without significantly altering the index.[21] Rare-earth elements, such as erbium, are doped into the core for active functionalities like optical amplification in erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs), where concentrations around 0.01-0.1 mol% enable efficient stimulated emission in the C-band.[22] Doping levels for GeO₂ typically range from 1 to 20 mol% in the core, balancing index elevation with scattering losses. The resulting index contrast, defined as Δ = (n₁ - n₂)/n₁, where n₁ is the core refractive index and n₂ is the cladding refractive index, approximates 0.3-1% for standard single-mode fibers. To calculate Δ, first determine the index change from doping: Δn ≈ (dn/dC) × C, with dn/dC ≈ 0.0015 for GeO₂ in silica (refractive index increment per mol%); for example, at C = 5 mol%, Δn ≈ 0.0075. Then, Δ ≈ Δn / n₁, yielding ≈ 0.52% assuming n₁ ≈ 1.45, which establishes the scale for light guidance in typical designs.[23]Types and Geometry

Core Diameter and Classification

The core diameter of an optical fiber is a critical parameter that determines the number of light modes it can support, thereby classifying fibers into single-mode and multimode categories. Single-mode fibers feature a small core diameter, typically ranging from 8 to 10 μm, which confines light propagation to the fundamental mode (LP01), eliminating intermodal dispersion for high-bandwidth applications over long distances.[24] These fibers adhere to standards such as ITU-T G.652, which specifies characteristics optimized for long-haul telecommunications, enabling transmission over tens to hundreds of kilometers without significant modal broadening.[25] In contrast, multimode fibers employ larger core diameters to accommodate multiple propagating modes, making them suitable for shorter-distance networks like local area networks (LANs). Step-index multimode fibers commonly have core diameters of 50 μm or 62.5 μm, where the abrupt refractive index change at the core-cladding boundary supports numerous modes but introduces modal dispersion that limits effective bandwidth.[26] Graded-index multimode fibers, with core diameters typically between 50 and 100 μm, mitigate this dispersion by gradually varying the refractive index across the core, allowing higher data rates over distances up to several hundred meters in LAN environments.[27] Plastic optical fibers (POF) represent another classification, utilizing even larger core diameters—often up to 1 mm—to facilitate low-cost, flexible applications in consumer and industrial settings. These fibers, primarily made from polymers like PMMA, support step-index multimode propagation and are widely used in automotive networks and home data links due to their ease of handling and tolerance for bends.[28] The choice of core diameter profoundly influences fiber performance and deployment. Smaller cores in single-mode fibers minimize intermodal dispersion, supporting terabit-per-second rates over long hauls, but necessitate precise alignment during coupling to avoid significant insertion losses.[29] Conversely, larger cores in multimode and POF designs enable simpler, less precise connections and higher light-gathering efficiency, though they restrict bandwidth-distance products to under 1 km for gigabit applications due to mode mixing effects.[30][27]Refractive Index Profiles

The refractive index profile of an optical fiber core describes the spatial variation of the refractive index within the core and at its boundary with the cladding, which significantly influences light propagation characteristics such as dispersion and mode confinement. In multimode fibers, the profile design is particularly important for managing modal dispersion, where different light paths travel at varying speeds.[1] The step-index profile features a uniform refractive index throughout the core, with an abrupt decrease at the core-cladding interface. This simple design is commonly used in multimode fibers, but it results in higher modal dispersion because axial rays travel faster than those near the core edge, limiting bandwidth over distance.[31] In contrast, the graded-index profile provides a gradual decrease in refractive index from the fiber axis toward the core edge, typically following a parabolic form given by where is the maximum refractive index on the axis, is the relative index difference, is the radial distance from the axis, and is the core radius.[32] This variation refracts higher-order modes more strongly, equalizing path speeds and optimizing bandwidth in multimode fibers.[33] Graded-index fibers were developed in the 1970s through joint efforts by Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation (now NTT) and companies like Sumitomo Electric, enabling practical multimode transmission systems.[34] Compared to step-index fibers, graded-index designs reduce modal dispersion by more than a factor of 100, substantially increasing achievable bandwidth.[35] The profile's effectiveness can be influenced by core diameter, as larger cores support more modes that benefit from the gradient.[1] Other refractive index profiles, such as triangular or those with depressed cladding, are employed in specialized single-mode fibers like dispersion-shifted types to tailor chromatic dispersion properties. A triangular profile features a linear decrease in index from the center, often combined with a lower-index trench in the cladding to shift the zero-dispersion wavelength toward longer operating bands around 1.55 μm, minimizing pulse broadening in high-bit-rate systems.[36] These designs enhance performance in wavelength-division multiplexing applications by optimizing dispersion without relying solely on core size adjustments.[37]Optical Properties

Refractive Index

The refractive index of the core, denoted as , is a fundamental property that governs light confinement in optical fibers. The refractive index of undoped fused silica is approximately 1.444 at a wavelength of 1550 nm, which serves as the baseline for the cladding refractive index . In standard fibers, the core is doped to achieve a slightly higher (typically 1.447–1.450), creating a small relative index difference (usually 0.3–0.35%) that enables total internal reflection.[38][29] In practice, the core refractive index is elevated through doping (e.g., with GeO₂) to create the required contrast with the undoped or down-doped cladding.[3] The refractive index of silica exhibits wavelength dependence, described by the Sellmeier equation, which models dispersion in transparent materials. For silica, a simplified form is , where is the wavelength in micrometers; the full equation incorporates additional terms with coefficients derived from empirical fits to account for ultraviolet and infrared resonances.[39] This dispersion ensures that decreases slightly at longer wavelengths like 1550 nm compared to visible light, influencing fiber performance in wavelength-division multiplexing systems. Doping with elements like germanium can fine-tune upward by up to 0.01 or more, depending on concentration.[40] Temperature variations affect the core refractive index through the thermo-optic coefficient for silica at room temperature, leading to potential signal drift in uncooled fiber systems over operational temperature ranges (e.g., –40°C to 85°C).[41] This coefficient arises primarily from changes in electronic polarizability and density with temperature, and it remains relatively stable across near-infrared wavelengths but can cause phase shifts in interferometric applications if uncompensated.[42] Post-fabrication verification of is essential to ensure fiber quality and is typically performed using interferometry or ellipsometry on preform slices or drawn fibers. Interferometry, such as Mach-Zehnder setups, measures phase shifts induced by the core material to map refractive index with sub-wavelength precision, often achieving resolutions better than 10^{-4}.[43] Ellipsometry complements this by analyzing polarized light reflection at oblique angles to determine non-destructively, particularly useful for validating uniformity in core regions.[44] These techniques confirm that the achieved matches design specifications, minimizing losses from index mismatches.Numerical Aperture and V-Number

The numerical aperture (NA) of an optical fiber core quantifies its ability to accept light rays from an external medium, serving as a key parameter in determining the fiber's light-gathering efficiency. It is defined mathematically as where is the refractive index of the core and is the refractive index of the surrounding cladding, with . This expression arises from ray optics principles applied to the fiber's geometry. Consider a meridional ray entering the fiber endface from air (refractive index ) at an angle to the fiber axis. At the core-cladding interface, for the ray to undergo total internal reflection and propagate, the angle of incidence must exceed the critical angle . By geometry, , where is the complement of the ray's angle inside the core after refraction at the endface. Applying Snell's law at the endface, , the maximum acceptance angle occurs when , yielding for . Thus, , defining the half-angle of the acceptance cone.[45] The V-number, also known as the normalized frequency parameter, provides a dimensionless measure of the waveguide's modal capacity and is given by where is the core radius and is the free-space wavelength of the light. This parameter encapsulates the effects of core size, wavelength, and refractive index contrast on mode propagation. For step-index fibers, the value of determines the number of guided modes: when , only the fundamental HE11 mode propagates, establishing single-mode operation; higher values support multiple modes in multimode fibers.[46][47] The implications of NA and V-number are critical for fiber design and performance. Multimode fibers typically feature higher NA values in the range of 0.2 to 0.5, which broaden the acceptance angle to facilitate easier coupling of light from sources like LEDs, but the larger index difference increases susceptibility to bend-induced losses and modal dispersion. In contrast, single-mode fibers employ lower NA around 0.1, enabling tighter confinement of light for minimal losses over long distances, though this demands precise alignment for efficient coupling from lasers. The V-number concept, rooted in mid-20th-century waveguide theory, was adapted to optical fibers during their development in the 1970s to predict modal behavior and optimize transmission purity.[48][49][50]Fabrication Methods

Preform Production

The production of optical fiber preforms involves vapor-phase deposition techniques that build the core region within a larger structure, enabling precise control over the refractive index profile essential for light guidance. These methods deposit silica-based materials doped with elements like germanium to form the core, which exhibits a higher refractive index than the surrounding cladding. The resulting preform serves as the precursor for drawing the final fiber, with the core region typically comprising 1-10 mm in diameter within an overall preform diameter of 20-40 mm.[51] Modified chemical vapor deposition (MCVD) is a widely adopted inside-tube process for preform fabrication. In MCVD, vapor-phase reactants such as silicon tetrachloride (SiCl₄) and germanium tetrachloride (GeCl₄) are introduced into a rotating fused silica substrate tube, typically 15-25 mm in outer diameter. An oxy-hydrogen burner traverses the tube's length, heating it to approximately 1400-1600°C, which induces chemical reactions that deposit thin layers of glass soot on the inner wall; these layers are simultaneously sintered into a porous deposit. Multiple passes allow buildup of the core region at the tube's center by varying dopant concentrations in successive layers, followed by collapse of the tube under heat to form a solid cylindrical preform with the integrated core-cladding structure. This method ensures high purity and uniformity in the core's refractive index profile through controlled layering of dopants like germanium for index elevation.[52][53] Outside vapor deposition (OVD) builds the preform externally, offering flexibility in core-cladding assembly. The process begins with the deposition of ultra-pure silica soot particles—generated from hydrolyzed vapors of SiCl₄ and dopants like GeCl₄—onto a rotating ceramic bait rod using an oxy-hydrogen flame. Layers of core material (germanium-doped silica) are applied first to form the central region, followed by undoped or fluorine-doped cladding layers, achieving precise radial buildup with thicknesses controlled to yield a core diameter of several millimeters. After sufficient deposition, the bait rod is removed, and the porous soot preform is sintered in a high-temperature furnace (around 1400-1500°C) under a chlorine atmosphere to consolidate it into a transparent glass boule, minimizing hydroxyl contamination for low-loss fibers. OVD's external layering facilitates customized core geometries, such as graded-index profiles via dopant variation across layers.[54][51] Vapor axial deposition (VAD) enables continuous, elongated preform growth along the axis, suitable for high-volume production. A seed rod advances axially while multiple oxy-hydrogen burners hydrolyze gaseous precursors (SiCl₄, GeCl₄, and others) into fine soot particles, which deposit at the rod's tip to form a growing boule; the core region develops at the center through targeted deposition from inner burners delivering higher dopant concentrations. This multi-burner setup allows simultaneous formation of core and cladding layers, with the boule extending to lengths of 1-2 meters and diameters up to 100 mm before sintering in a furnace to densify the structure. VAD's axial progression supports scalable core formation with controlled index profiles by adjusting burner positions and gas flows during growth.[55][56] Across these techniques, the core's refractive index profile is precisely engineered by sequential dopant layering during deposition, integrating doping directly into the preform synthesis for optimal light confinement. Typical preforms measure 20-40 mm in diameter and 30-50 cm in length, with the core region scaled to 1-10 mm to match the magnification factor (about 1000:1) for drawing into final fiber diameters.[51]Fiber Drawing Process

The fiber drawing process transforms the preform, which incorporates the core structure, into the final optical fiber by heating and elongating it in a controlled manner. The preform is gradually lowered into a drawing furnace heated to approximately 2000°C, where the silica softens sufficiently for pulling. A seed fiber is attached to the bottom of the preform, and the softened material is drawn downward at speeds typically ranging from 10 to 20 m/s using capstans, reducing the preform's diameter from several millimeters to a standard 125 μm for the overall fiber cladding while the core scales proportionally, for example, to about 8-10 μm in single-mode fibers. This reduction preserves the refractive index profile and core geometry essential for light guidance.[57][58][59] Precise control during drawing is critical to maintain core integrity and uniformity. Tension is regulated between 0.1 and 1 N to minimize deviations in core shape, ensuring ellipticity remains below 1% and preventing birefringence that could affect signal propagation. Fiber diameter is continuously monitored using laser interferometry, which provides sub-micrometer accuracy by analyzing interference patterns from light scattered off the fiber surface, allowing real-time adjustments to drawing parameters for consistent core dimensions.[60] To protect the vulnerable glass core from moisture, scratches, and contaminants that could increase optical losses, a polymer coating—typically a dual-layer acrylate system—is applied immediately after drawing while the fiber is still bare and traveling at high speed. This coating, cured by ultraviolet light, encapsulates the core and cladding without altering their optical properties.[61][62] The process originated with the first commercial demonstration by Corning in 1970, yielding fibers with 20 dB/km attenuation limited by core impurities and drawing inconsistencies. By the 1980s, refinements in drawing techniques, including better temperature uniformity and tension control, achieved losses as low as 0.2 dB/km, primarily through improved core homogeneity that reduced scattering.[19][63]References

- https://www.[mdpi](/page/MDPI).com/2076-3417/7/12/1295