Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cephalosporin

View on Wikipedia

| Cephalosporin | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Core structure of the cephalosporins | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Bacterial infection |

| ATC code | J01D |

| Biological target | Penicillin binding proteins |

| Clinical data | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D002511 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

The cephalosporins (sg. /ˌsɛfələˈspɔːrɪn, ˌkɛ-, -loʊ-/[1][2]) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus Acremonium, which was previously known as Cephalosporium.[3]

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibiotics called cephems. Cephalosporins were discovered in 1945, and first sold in 1964.[4]

Discovery

[edit]The aerobic mold which yielded cephalosporin C was found in the sea near a sewage outfall in Su Siccu, by Cagliari harbour in Sardinia, by the Italian pharmacologist Giuseppe Brotzu in July 1945.[5]

Structure

[edit]Cephalosporin contains a 6-membered dihydrothiazine ring. Substitutions at position 3 generally affect pharmacology; substitutions at position 7 affect antibacterial activity, but these cases are not always true.[6]

Medical uses

[edit]Cephalosporins can be indicated for the prophylaxis and treatment of infections caused by bacteria susceptible to this particular form of antibiotic. First-generation cephalosporins are active predominantly against Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.[7] They are therefore used mostly for skin and soft tissue infections and the prevention of hospital-acquired surgical infections.[8] Successive generations of cephalosporins have increased activity against Gram-negative bacteria, albeit often with reduced activity against Gram-positive organisms.[citation needed]

The antibiotic may be used for patients who are allergic to penicillin due to the different β-lactam antibiotic structure. The drug is able to be excreted in the urine.[7]

Side effects

[edit]Common adverse drug reactions (ADRs) (≥ 1% of patients) associated with the cephalosporin therapy include: diarrhea, nausea, rash, electrolyte disturbances, and pain and inflammation at injection site. Infrequent ADRs (0.1–1% of patients) include vomiting, headache, dizziness, oral and vaginal candidiasis, pseudomembranous colitis, superinfection, eosinophilia, nephrotoxicity, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and fever.[citation needed]

Allergic hypersensitivity

[edit]The commonly quoted figure of 10% of patients with allergic hypersensitivity to penicillins or carbapenems also having cross-reactivity with cephalosporins originated from a 1975 study looking at the original cephalosporins,[9] and subsequent "safety first" policy meant this was widely quoted and assumed to apply to all members of the group.[10] Hence, it was commonly stated that they are contraindicated in patients with a history of severe, immediate allergic reactions (urticaria, anaphylaxis, interstitial nephritis, etc.) to penicillins or carbapenems.[11]

The contraindication, however, should be viewed in the light of recent epidemiological work suggesting, for many second-generation (or later) cephalosporins, the cross-reactivity rate with penicillin is much lower, having no significantly increased risk of reactivity over the first generation based on the studies examined.[10][12] The British National Formulary previously issued blanket warnings of 10% cross-reactivity, but, since the September 2008 edition, suggests, in the absence of suitable alternatives, oral cefixime or cefuroxime and injectable cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and ceftriaxone can be used with caution, but the use of cefaclor, cefadroxil, cefalexin, and cefradine should be avoided.[13] A 2012 literature review similarly finds that the risk is negligible with third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins. The risk with first-generation cephalosporins having similar R1 sidechains was also found to be overestimated, with the real value closer to 1%.[14]

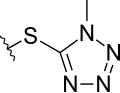

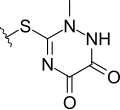

MTT side chain

[edit]Several cephalosporins are associated with hypoprothrombinemia and a disulfiram-like reaction with ethanol.[15][16] These include latamoxef (moxalactam), cefmenoxime, cefoperazone, cefamandole, cefmetazole, and cefotetan. This is thought to be due to the methylthiotetrazole side-chain of these cephalosporins, which blocks the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase (likely causing hypothrombinemia) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (causing alcohol intolerance).[17] Thus, consumption of alcohol after taking these cephalosporin orally or intravenously is contraindicated, and in severe cases can lead to death.[18] The methylthiodioxotriazine sidechain found in ceftriaxone has a similar effect. Cephalosporins without these structural elements are believed to be safe with alcohol.[19]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Cephalosporins are bactericidal and, like other β-lactam antibiotics, disrupt the synthesis of the peptidoglycan layer forming the bacterial cell wall. The peptidoglycan layer is important for cell wall structural integrity. The final transpeptidation step in the synthesis of the peptidoglycan is facilitated by penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). PBPs bind to the D-Ala-D-Ala at the end of muropeptides (peptidoglycan precursors) to crosslink the peptidoglycan. Beta-lactam antibiotics mimic the D-Ala-D-Ala site, thereby irreversibly inhibiting PBP crosslinking of peptidoglycan.[20]

Resistance

[edit]Resistance to cephalosporin antibiotics can involve either reduced affinity of existing PBP components or the acquisition of a supplementary β-lactam-insensitive PBP. Compared to other β-lactam antibiotics (such as penicillins), they are less susceptible to β-lactamases. Currently, some Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Escherichia coli strains are resistant to cephalosporins. Some Morganella morganii, Proteus vulgaris, Providencia rettgeri, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Serratia marcescens and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains have also developed resistance to cephalosporins to varying degrees.[21][22]

Classification

[edit]The first cephalosporins were designated first-generation cephalosporins, whereas, later, more extended-spectrum cephalosporins were classified as second-generation cephalosporins. Each newer generation has significantly greater Gram-negative antimicrobial properties than the preceding generation, in most cases with decreased activity against Gram-positive organisms. Fourth-generation cephalosporins, however, have true broad-spectrum activity.[23]

The classification of cephalosporins into "generations" is commonly practised, although the exact categorization is often imprecise. For example, the fourth generation of cephalosporins is not recognized as such in Japan.[citation needed] In Japan, cefaclor is classed as a first-generation cephalosporin, though in the United States it is a second-generation one; and cefbuperazone, cefminox, and cefotetan are classed as second-generation cephalosporins.

First generation

[edit]Cefalotin, cefazolin, cefalexin, cefapirin, cefradine, and cefadroxil are among the drugs belonging to this group.

Second generation

[edit]Cefoxitin, cefuroxime, cefaclor, cefprozil, and cefmetazole are classed as second-generation cephems.

Third generation

[edit]Ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime are classed as third-generation cephalosporins. Flomoxef and latamoxef are in a new, related class called oxacephems.[24]

Fourth generation

[edit]Drugs included in this group are cefepime and cefpirome.

Further generations

[edit]Some state that cephalosporins can be divided into five or even six generations, although the usefulness of this organization system is of limited clinical relevance.[25]

Naming

[edit]Most first-generation cephalosporins were originally spelled "ceph-" in English-speaking countries. This continues to be the preferred spelling in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, while European countries (including the United Kingdom) have adopted the International Nonproprietary Names, which are always spelled "cef-". Newer first-generation cephalosporins and all cephalosporins of later generations are spelled "cef-", even in the United States.[citation needed]

Activity

[edit]There exist bacteria which cannot be treated with cephalosporins of generations first through fourth:[26]

- Listeria spp.

- Atypicals (including Mycoplasma and Chlamydia)

- MRSA

- Enterococci

Fifth-generation cephalosporins (e.g. ceftaroline) are effective against MRSA, Listeria spp., and Enterococcus faecalis.[27][26]

Overview table

[edit]

Generation

|

Name | Approval status

|

Coverage

|

Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common | Alternate name or spelling | Brand | ||||

| (#) = noncephalosporins similar to generation # | H, human; V, veterinary; W, withdrawn; P, Pseudomonas; MR, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; An, anaerobe | |||||

| 1 | Cefalexin | cephalexin | Keflex | H V | Gram-positive: Activity against penicillinase-producing, methicillin-susceptible staphylococci and streptococci (though they are not the drugs of choice for such infections). No activity against methicillin-resistant staphylococci or enterococci.[citation needed]

Gram-negative: Activity against Proteus mirabilis, some Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ("PEcK"), but have no activity against Bacteroides fragilis, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Enterobacter, indole-positive Proteus, or Serratia.[citation needed] | |

| Cefadroxil | cefadroxyl | Duricef | H | |||

| Cefazolin | cephazolin | Ancef, Kefzol | H | |||

| Cefapirin | cephapirin | Cefadryl | V | |||

| Cefacetrile | cephacetrile | |||||

| Cefaloglycin | cephaloglycin | |||||

| Cefalonium | cephalonium | |||||

| Cefaloridine | cephaloradine | |||||

| Cefalotin | cephalothin | Keflin | ||||

| Cefatrizine | ||||||

| Cefazaflur | ||||||

| Cefazedone | ||||||

| Cefradine | cephradine | Velosef | ||||

| Cefroxadine | ||||||

| Ceftezole | ||||||

| 2 | Cefuroxime | Altacef, Zefu, Zinnat, Zinacef, Ceftin, Biofuroksym,[28] Xorimax | H | Gram-positive: Less than first-generation.[citation needed]

Gram-negative: Greater than first-generation: HEN Haemophilus influenzae, Enterobacter aerogenes and some Neisseria + the PEcK described above.[citation needed] | ||

| Cefprozil | cefproxil | Cefzil | H | |||

| Cefaclor | Ceclor, Distaclor, Keflor, Raniclor | H | ||||

| Cefonicid | Monocid | |||||

| Cefuzonam | ||||||

| Cefamandole | W | |||||

| (2) | Cefoxitin | Mefoxin | H | An | Cephamycins sometimes grouped with second-generation cephalosporins | |

| Cefotetan | Cefotan | H | An | |||

| Cefmetazole | Zefazone | An | ||||

| Cefminox | ||||||

| Cefbuperazone | ||||||

| Cefotiam | Pansporin | |||||

| Loracarbef | Lorabid | The carbacephem analog of cefaclor | ||||

| 3 | Cefdinir | Sefdin, Zinir, Omnicef, Kefnir | H | Gram-positive: Some members of this group (in particular, those available in an oral formulation, and those with antipseudomonal activity) have decreased activity against gram-positive organisms.

Activity against staphylococci and streptococci is less with the third-generation compounds than with the first- and second-generation compounds.[29] Gram-negative: Third-generation cephalosporins have a broad spectrum of activity and further increased activity against gram-negative organisms. They may be particularly useful in treating hospital-acquired infections, although increasing levels of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases are reducing the clinical utility of this class of antibiotics. They are also able to penetrate the central nervous system, making them useful against meningitis caused by pneumococci, meningococci, H. influenzae, and susceptible E. coli, Klebsiella, and penicillin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae. Since August 2012, the third-generation cephalosporin, ceftriaxone, is the only recommended treatment for gonorrhea in the United States (in addition to azithromycin or doxycycline for concurrent Chlamydia treatment). Cefixime is no longer recommended as a first-line treatment due to evidence of decreasing susceptibility.[30] | ||

| Ceftriaxone | Rocephin | H | ||||

| Ceftazidime | Meezat, Fortum, Fortaz | H | P | |||

| Cefixime | Fixx, Zifi, Suprax | H | ||||

| Cefpodoxime | Vantin, PECEF, Simplicef | H V | ||||

| Ceftiofur | Naxcel, Excenel | H V | ||||

| Cefotaxime | Claforan | H | ||||

| Ceftizoxime | Cefizox | H | ||||

| Cefditoren | Zostom-O | H | ||||

| Ceftibuten | Cedax | H | ||||

| Cefovecin | Convenia | V | ||||

| Cefdaloxime | ||||||

| Cefcapene | ||||||

| Cefetamet | ||||||

| Cefmenoxime | ||||||

| Cefodizime | ||||||

| Cefpimizole | ||||||

| Cefteram | ||||||

| Ceftiolene | ||||||

| Cefoperazone | Cefobid | W[31] | P | |||

| (3) | Latamoxef | moxalactam | W[31] | An oxacephem sometimes grouped with third-generation cephalosporins | ||

| 4 | Cefepime | Maxipime | H | P | Gram-positive: They are extended-spectrum agents with similar activity against Gram-positive organisms as first-generation cephalosporins.[citation needed]

Gram-negative: Fourth-generation cephalosporins are zwitterions that can penetrate the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria.[32] They also have a greater resistance to β-lactamases than the third-generation cephalosporins. Many can cross the blood–brain barrier and are effective in meningitis. They are also used against Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[citation needed] Cefiderocol has been called a fourth-generation cephalosporin by only one source as of November 2019.[33] | |

| Cefiderocol | Fetroja | H | ||||

| Cefquinome | V | |||||

| Cefclidine | ||||||

| Cefluprenam | ||||||

| Cefoselis | ||||||

| Cefozopran | ||||||

| Cefpirome | Cefrom | |||||

| (4) | Flomoxef | An oxacephem sometimes grouped with fourth-generation cephalosporins | ||||

| 5 | Ceftaroline | H | MR | Ceftobiprole has been described as "fifth-generation" cephalosporin,[34][35] though acceptance for this terminology is not universal. Ceftobiprole has anti-pseudomonal activity and appears to be less susceptible to development of resistance. Ceftaroline has also been described as "fifth-generation" cephalosporin, but does not have the activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa or vancomycin-resistant enterococci that ceftobiprole has.[36] Ceftolozane is an option for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections and complicated urinary tract infections. It is combined with the β-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam, as multi-drug resistant bacterial infections will generally show resistance to all β-lactam antibiotics unless this enzyme is inhibited.[37][38][39][40][41] | ||

| Ceftolozane | Zerbaxa | H | ||||

| Ceftobiprole | MR | |||||

| ? | Cefaloram | These cephems have progressed far enough to be named, but have not been assigned to a particular generation. Nitrocefin is a chromogenic cephalosporin substrate, and is used for detection of β-lactamases.[citation needed] | ||||

| Cefaparole | ||||||

| Cefcanel | ||||||

| Cefedrolor | ||||||

| Cefempidone | ||||||

| Cefetrizole | ||||||

| Cefivitril | ||||||

| Cefmatilen | ||||||

| Cefmepidium | ||||||

| Cefoxazole | ||||||

| Cefrotil | ||||||

| Cefsumide | ||||||

| Ceftioxide | ||||||

| Cefuracetime | ||||||

| Nitrocefin | ||||||

History

[edit]Cephalosporin compounds were first isolated from cultures of Acremonium strictum from a sewer in Sardinia in 1948 by Italian scientist Giuseppe Brotzu.[42] He noticed these cultures produced substances that were effective against Salmonella typhi, the cause of typhoid fever, which had β-lactamase. Guy Newton and Edward Abraham at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology at the University of Oxford isolated cephalosporin C. The cephalosporin nucleus, 7-aminocephalosporanic acid (7-ACA), was derived from cephalosporin C and proved to be analogous to the penicillin nucleus 6-aminopenicillanic acid (6-APA), but it was not sufficiently potent for clinical use. Modification of the 7-ACA side chains resulted in the development of useful antibiotic agents, and the first agent, cefalotin (cephalothin), was launched by Eli Lilly and Company in 1964.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ "cephalosporin". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "cephalosporin – definition of cephalosporin in English from the Oxford dictionary". OxfordDictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "cephalosporin" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Oxford Handbook of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology. OUP Oxford. 2009. p. 56. ISBN 9780191039621.

- ^ Tilli Tansey, Lois Reynolds, eds. (2000). Post Penicillin Antibiotics: From acceptance to resistance?. Wellcome Witnesses to Contemporary Medicine. History of Modern Biomedicine Research Group. ISBN 978-1-84129-012-6. OL 12568269M. Wikidata Q29581637.

- ^ Prince A. "Cephalosporins and vancomycin" (PDF). Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Cephalosporins – Infectious Diseases". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Pandey N, Cascella M (2020). "Beta Lactam Antibiotics". StatPearls. StatPearls. PMID 31424895.

- ^ Dash CH (1 September 1975). "Penicillin allergy and the cephalosporins". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1 (3 Suppl): 107–118. doi:10.1093/jac/1.suppl_3.107. PMID 1201975.

- ^ a b Pegler S, Healy B (November 2007). "In patients allergic to penicillin, consider second and third generation cephalosporins for life threatening infections". BMJ. 335 (7627): 991. doi:10.1136/bmj.39372.829676.47. PMC 2072043. PMID 17991982.

- ^ Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.[page needed]

- ^ Pichichero ME (February 2006). "Cephalosporins can be prescribed safely for penicillin-allergic patients". The Journal of Family Practice. 55 (2): 106–112. PMID 16451776.

- ^ "5.1.2 Cephalosporins and other beta-lactams". British National Formulary (56 ed.). London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and Royal Pharmaceutical Society Publishing. September 2008. pp. 295. ISBN 978-0-85369-778-7.

- ^ Campagna JD, Bond MC, Schabelman E, Hayes BD (May 2012). "The use of cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients: a literature review". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 42 (5): 612–620. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.035. PMID 21742459.

- ^ Kitson TM (May 1987). "The effect of cephalosporin antibiotics on alcohol metabolism: a review". Alcohol. 4 (3): 143–148. doi:10.1016/0741-8329(87)90035-8. PMID 3593530.

- ^ Shearer MJ, Bechtold H, Andrassy K, Koderisch J, McCarthy PT, Trenk D, et al. (January 1988). "Mechanism of cephalosporin-induced hypoprothrombinemia: relation to cephalosporin side chain, vitamin K metabolism, and vitamin K status". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 28 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03106.x. PMID 3350995. S2CID 30591177.

- ^ Stork CM (2006). "Antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals". In Nelson LH, Flomenbaum N, Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RL, Howland MD, Lewin NA (eds.). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 847. ISBN 978-0-07-143763-9.

- ^ Ren S, Cao Y, Zhang X, Jiao S, Qian S, Liu P (2014). "Cephalosporin induced disulfiram-like reaction: a retrospective review of 78 cases". International Surgery. 99 (2): 142–146. doi:10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00086.1. PMC 3968840. PMID 24670024.

- ^ Mergenhagen KA, Wattengel BA, Skelly MK, Clark CM, Russo TA (February 2020). "Fact versus Fiction: a Review of the Evidence behind Alcohol and Antibiotic Interactions". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 64 (3) e02167-19. doi:10.1128/aac.02167-19. PMC 7038249. PMID 31871085.

- ^ Tipper DJ, Strominger JL (October 1965). "Mechanism of action of penicillins: a proposal based on their structural similarity to acyl-D-alanyl-D-alanine". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 54 (4): 1133–1141. Bibcode:1965PNAS...54.1133T. doi:10.1073/pnas.54.4.1133. PMC 219812. PMID 5219821.

- ^ "Cephalosporin spectrum of resistance". Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Sutaria DS, Moya B, Green KB, Kim TH, Tao X, Jiao Y, et al. (June 2018). "First Penicillin-Binding Protein Occupancy Patterns of β-Lactams and β-Lactamase Inhibitors in Klebsiella pneumoniae". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 62 (6) e00282-18. doi:10.1128/AAC.00282-18. PMC 5971569. PMID 29712652.

- ^ "Cephalosporins – Infectious Diseases – Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ Narisada M, Tsuji T (1990). "1-Oxacephem Antibiotics". Recent Progress in the Chemical Synthesis of Antibiotics. pp. 705–725. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-75617-7_19. ISBN 978-3-642-75619-1.

- ^ "Case Based Pediatrics Chapter".

- ^ a b Bui T, Preuss CV (2023). "Cephalosporins". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31855361. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Duplessis C, Crum-Cianflone NF (February 2011). "Ceftaroline: A New Cephalosporin with Activity against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)". Clinical Medicine Reviews in Therapeutics. 3: a2466. doi:10.4137/CMRT.S1637. PMC 3140339. PMID 21785568.

- ^ Jędrzejczyk T. "Internetowa Encyklopedia Leków". leki.med.pl. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- ^ Scholar EM, Pratt WB (2000). "Four The Inhibitors of Cell Wall Synthesis, II: Pharmacology and Adverse Effects of the Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Carbapenems, Monobactams, Vancomycin, and Bacitracin". The Antimicrobial Drugs. Oxford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-19-512528-3.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (August 2012). "Update to CDC's Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 61 (31): 590–594. PMID 22874837.

- ^ a b Arumugham VB, Gujarathi R, Cascella M (January 2021). "Third Generation Cephalosporins". StatPearls. StatPearls. PMID 31751071.

- ^ Richard L Sweet, Ronald S. Gibbs (1 March 2009). Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 403–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7815-2. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "CHEBI:140376 – cefiderocol". ebi.ac.uk. EMBL-EBI. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ Widmer AF (March 2008). "Ceftobiprole: a new option for treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus" (PDF). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 46 (5): 656–658. doi:10.1086/526528. PMID 18225983.

- ^ Kosinski MA, Joseph WS (July 2007). "Update on the treatment of diabetic foot infections". Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 24 (3): 383–96, vii. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2007.03.009. PMID 17613382.

- ^ Kollef MH (December 2009). "New antimicrobial agents for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus". Critical Care and Resuscitation. 11 (4): 282–286. doi:10.1016/S1441-2772(23)01290-5. PMID 20001879.

- ^ Takeda S, Nakai T, Wakai Y, Ikeda F, Hatano K (March 2007). "In vitro and in vivo activities of a new cephalosporin, FR264205, against Pseudomonas aeruginosa". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 51 (3): 826–830. doi:10.1128/AAC.00860-06. PMC 1803152. PMID 17145788.

- ^ Toda A, Ohki H, Yamanaka T, Murano K, Okuda S, Kawabata K, et al. (September 2008). "Synthesis and SAR of novel parenteral anti-pseudomonal cephalosporins: discovery of FR264205". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 18 (17): 4849–4852. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.085. PMID 18701284.

- ^ Sader HS, Rhomberg PR, Farrell DJ, Jones RN (May 2011). "Antimicrobial activity of CXA-101, a novel cephalosporin tested in combination with tazobactam against Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Bacteroides fragilis strains having various resistance phenotypes". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 55 (5): 2390–2394. doi:10.1128/AAC.01737-10. PMC 3088243. PMID 21321149.

- ^ Craig WA, Andes DR (April 2013). "In vivo activities of ceftolozane, a new cephalosporin, with and without tazobactam against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae, including strains with extended-spectrum β-lactamases, in the thighs of neutropenic mice". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 57 (4): 1577–1582. doi:10.1128/AAC.01590-12. PMC 3623364. PMID 23274659.

- ^ Zhanel GG, Chung P, Adam H, Zelenitsky S, Denisuik A, Schweizer F, et al. (January 2014). "Ceftolozane/tazobactam: a novel cephalosporin/β-lactamase inhibitor combination with activity against multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli". Drugs. 74 (1): 31–51. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0168-2. PMID 24352909. S2CID 44694926.

- ^ Podolsky DK (1998). Cures out of Chaos. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-2973-8.[page needed]

External links

[edit]Cephalosporin

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and General Properties

Cephalosporins are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus Acremonium (previously known as Cephalosporium).[1] They possess a β-lactam ring that is essential for their antimicrobial activity.[7] These antibiotics exhibit bactericidal properties by inhibiting bacterial cell wall synthesis, demonstrating broad-spectrum activity against many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.[1] Certain cephalosporins also show stability against some β-lactamases produced by bacteria, enhancing their efficacy in specific infections.[7] Representative examples include cephalexin, an oral first-generation cephalosporin with a molecular weight of 347.4 g/mol and solubility of approximately 10 mg/mL in water at room temperature, suitable for outpatient use.[9] Another is ceftriaxone, a parenteral third-generation cephalosporin with a molecular weight of 661.6 g/mol for its sodium salt and solubility of approximately 100-400 mg/mL in water, often administered intravenously.[10] Cephalosporins share a structural relation to penicillins through their common β-lactam ring but generally exhibit lower rates of allergic cross-reactivity, estimated at less than 2% for IgE-mediated reactions in penicillin-allergic patients, though this can vary based on side chain similarities.[11][12]Clinical Importance

Cephalosporins represent one of the most frequently prescribed antibiotic classes globally, forming a substantial portion of overall antibiotic utilization in both community and hospital settings. In the United States, outpatient prescriptions for cephalosporins reached 38.9 million in 2023, equating to 116 prescriptions per 1,000 population.[13] In hospital environments, particularly across low- and middle-income countries, third-generation cephalosporins account for 15.5% to 22% of antibiotic prescriptions as of 2023, underscoring their prominence in treating acute infections.[14] The therapeutic advantages of cephalosporins lie in their broad versatility, enabling effective management of community-acquired infections like pneumonia and urinary tract infections, as well as nosocomial infections in vulnerable patients. They are particularly valued for prophylactic applications in surgery, where administration has been demonstrated to reduce postoperative morbidity and surgical site infections by up to 50% compared to no prophylaxis. This dual role in empirical therapy and prevention positions cephalosporins as essential tools in clinical practice.[1][15][16] From an economic perspective, the global cephalosporin market was valued at USD 19.38 billion in 2023, with projections for continued growth driven by expanding demand in emerging markets. The availability of generic formulations has significantly enhanced cost-effectiveness, with daily treatment costs for generics often one-fourth to one-half lower than brand-name versions, thereby improving access and reducing overall healthcare expenditures in resource-constrained environments.[17][18][19] In public health, cephalosporins are recognized for their critical contributions, with key agents such as ceftriaxone and cefotaxime featured on the World Health Organization's Model List of Essential Medicines for their proven efficacy against severe bacterial infections. Their appropriate use has played a key role in lowering mortality rates from bacterial diseases by enabling timely and effective treatment, though this impact is tempered by rising resistance patterns that necessitate stewardship efforts.[20]History

Discovery

In 1945, Italian microbiologist Giuseppe Brotzu, professor of hygiene at the University of Cagliari, isolated the fungus Cephalosporium acremonium (now classified as Acremonium chrysogenum) from seawater samples collected near a sewage outlet in the harbor of Cagliari, Sardinia.[21] Motivated by the regional prevalence of typhoid fever and the need for antibiotics effective against gram-negative bacteria like Salmonella typhi, Brotzu cultured the fungus and observed that its filtrates inhibited the growth of S. typhi as well as Staphylococcus aureus.[22] These initial experiments demonstrated the potential of the fungal metabolite as a therapeutic agent, though production yields were low and purification rudimentary. Brotzu published his findings in a 1948 report and forwarded samples of the fungus along with detailed observations to Howard Florey at the University of Oxford.[21] Due to Florey's commitments to penicillin scale-up during postwar reconstruction, the material was redirected to Ernst Chain and Edward P. Abraham at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, initiating a key collaboration.[22] The Oxford team replicated Brotzu's cultures and began systematic fractionation of the broth in 1948, aiming to identify active principles resistant to bacterial enzymes that degraded penicillin.[23] By 1949, Abraham and his colleague Guy Newton isolated cephalosporin N (also termed penicillin N), a hydrophilic beta-lactam compound structurally related to penicillin, exhibiting activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.[5] However, cephalosporin N faced significant early challenges, including chemical instability in solution and susceptibility to hydrolysis by penicillinase enzymes produced by resistant bacteria, which curtailed further development as a direct therapeutic.[23] Attention shifted to other components in the filtrate, leading to the purification of cephalosporin C in 1953—a stable, penicillinase-resistant antibiotic with a novel bicyclic beta-lactam nucleus but modest potency against clinical pathogens. Throughout the 1950s, the Oxford group and emerging pharmaceutical collaborators, including Eli Lilly, conducted extensive screening of over 400 semi-synthetic derivatives derived from the cephalosporin C nucleus, modifying side chains to enhance antibacterial efficacy and stability.[21] These efforts revealed cephalosporin C's value as a versatile scaffold, overcoming the limitations of earlier isolates and establishing the foundation for a new class of beta-lactam antibiotics.[22]Development and Commercialization

In the 1960s, Eli Lilly and Company pioneered semi-synthetic modifications of the natural cephalosporin nucleus, transforming it from a lab curiosity into viable therapeutic agents. These innovations focused on improving stability and pharmacokinetics, culminating in the development of first-generation cephalosporins like cephalothin, which received FDA approval in 1964 for parenteral use against Gram-positive infections.[24] The push toward oral formulations accelerated in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with companies such as Eli Lilly and Glaxo Laboratories playing key roles in patenting and commercializing absorbable derivatives. A landmark example was cephalexin, an oral first-generation cephalosporin approved by the FDA in 1970, enabling outpatient treatment of mild infections and broadening accessibility beyond hospital settings.[25][26] By the 1970s and 1980s, rising bacterial resistance to earlier antibiotics, particularly β-lactamases hydrolyzing first- and second-generation agents, drove the industry toward broader-spectrum cephalosporins. Pharmaceutical firms invested in structural tweaks to enhance Gram-negative coverage while retaining Gram-positive activity, shifting focus from narrow to expanded indications amid global resistance trends.[27][24] Key milestones marked this progression: third-generation cephalosporins like ceftazidime, developed by Glaxo and FDA-approved in 1985, offered improved penetration against Pseudomonas and other resistant Gram-negatives; fourth-generation agents such as cefepime, approved in 1996 by Bristol-Myers Squibb, provided balanced dual coverage and β-lactamase stability; and fifth-generation options including ceftaroline, approved in 2010 by Cerexa (now Allergan), targeted MRSA alongside Gram-negatives. These advancements resulted in over 50 cephalosporins approved globally by 2025, spanning five generations and diverse administration routes.[28][24][29][30] Post-2020 developments addressed multidrug-resistant threats, exemplified by cefiderocol, a siderophore-conjugated cephalosporin approved by the FDA in 2019 for complicated urinary tract infections and expanded in 2020 to hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia in adults with limited alternatives.[31][32] In 2024, the FDA approved ceftobiprole medocaril (Zevtera), a fifth-generation cephalosporin, for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (including right-sided endocarditis), acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections, and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia in adults.[33]Chemical Structure

Core Molecular Framework

The core molecular framework of cephalosporins is embodied in 7-aminocephalosporanic acid (7-ACA), a bicyclic structure comprising a four-membered β-lactam ring fused to a six-membered dihydrothiazine ring, forming the cephem nucleus.[34] This fusion creates a rigid scaffold that distinguishes cephalosporins within the β-lactam class, with the dihydrothiazine ring providing conformational stability to the overall molecule.[35] Key functional groups on this core include a carboxyl group at position 4 of the dihydrothiazine ring, which contributes to solubility and ionization properties, and an amino group at position 7 of the β-lactam ring, serving as the primary site for acylation during semi-synthetic modifications.[36] The β-lactam ring itself exhibits high reactivity due to the strained amide bond, enabling nucleophilic attack by bacterial enzymes, while the adjacent dihydrothiazine ring modulates this reactivity to enhance chemical stability against hydrolysis.[37] Cephalosporin C, the naturally occurring precursor isolated from Acremonium fungi, exemplifies this framework with the molecular formula C₁₆H₂₁N₃O₈S and a molecular weight of 415.42 g/mol.[38] In comparison to penicillins, which feature a β-lactam ring fused to a five-membered thiazolidine ring, the six-membered dihydrothiazine ring in cephalosporins introduces greater bulkiness, reducing steric hindrance around the β-lactam and conferring improved resistance to β-lactamase degradation.[39]Modifications Across Generations

Cephalosporins are structurally modified from the core 7-aminocephalosporanic acid framework primarily at the 7β-acylamino side chain and the 3-position of the dihydrothiazine ring to optimize their pharmacological properties. These alterations define the generational classifications and influence key aspects such as antibacterial potency and resistance profiles.[40] Modifications to the position 7 side chain involve varying acyl groups that significantly impact interactions with bacterial targets. In third-generation cephalosporins, the incorporation of an aminothiazolyl moiety at this position enhances Gram-negative activity by improving binding affinity to penicillin-binding proteins and facilitating better penetration into bacterial cells.[41] This structural feature, often combined with a syn-(Z)-methoxyimino group, also confers greater stability against hydrolysis by β-lactamases produced by Gram-negative pathogens, thereby broadening efficacy against resistant strains.[42] At the position 3 side chain, substituents are tailored to modulate absorption and duration of action. Oral first-generation cephalosporins typically feature a methyl group at the 3-position, which supports oral bioavailability. In contrast, parenteral first-generation agents like cephalothin retain the acetoxymethyl group.[43] Third-generation agents like ceftriaxone incorporate a complex heterocyclic thiomethyl derivative at position 3 (specifically, a 1,2,4-triazinone-thiomethyl group), which sterically hinders enzymatic degradation and contributes to prolonged systemic exposure through altered clearance pathways.[44][45] Additional structural innovations appear in later generations to address specific challenges. Fourth-generation cephalosporins, such as cefepime, adopt zwitterionic configurations—bearing both positive and negative charges within the molecule—which enhance stability in renal environments and reduce susceptibility to hydrolysis by certain β-lactamases.[42] Newer agents like cefiderocol introduce siderophore conjugation, attaching a catechol moiety to the position 3 side chain to exploit bacterial iron uptake systems for improved intracellular delivery.[46] Structure-activity relationships reveal that these modifications directly correlate with functional outcomes. For instance, the methoxyimino group at position 7 sterically protects the β-lactam ring from nucleophilic attack by β-lactamases, while polar extensions at position 3 enhance membrane permeability across outer bacterial envelopes without compromising core integrity.[47] Such targeted changes underscore the evolution of cephalosporins from narrow-spectrum agents to versatile therapeutics resistant to common resistance mechanisms.[48]Mechanism of Action

Inhibition of Bacterial Cell Wall Synthesis

Cephalosporins exert their antibacterial effect by binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are essential enzymes involved in the final stages of peptidoglycan synthesis in the bacterial cell wall. In Gram-positive bacteria, cephalosporins demonstrate high affinity for PBPs 1A, 1B, 2, and 3, which catalyze transpeptidation and transglycosylation reactions necessary for cross-linking peptidoglycan chains.[1] In Gram-negative bacteria, their affinity is particularly notable for PBP-2, contributing to the disruption of cell wall integrity in these organisms.[35] The binding process involves the reactive β-lactam ring of the cephalosporin molecule, which mimics the D-alanyl-D-alanine terminus of peptidoglycan precursors. This ring opens upon interaction with the active site serine residue of the PBP, leading to acylation where the serine forms a covalent bond with the β-lactam carbonyl carbon. This acylation irreversibly inhibits the transpeptidase activity of the PBP, preventing the cross-linking of peptidoglycan strands.[35] The simplified reaction can be represented as: As a result of PBP inhibition, uncross-linked peptidoglycan precursors accumulate in the periplasmic space, weakening the cell wall and activating autolytic enzymes that degrade the existing peptidoglycan structure. This leads to osmotic instability and eventual bacterial cell lysis and death. Cephalosporins exhibit time-dependent killing, where efficacy correlates more with the duration of exposure above the minimum inhibitory concentration rather than peak concentration.[1][49]Spectrum of Activity Fundamentals

Cephalosporins exhibit strong antibacterial activity against many Gram-positive bacteria, primarily through their binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) essential for cell wall synthesis. This interaction is particularly effective against staphylococci and streptococci, where cephalosporins acylate PBPs 1, 2, and 3, leading to inhibition of peptidoglycan cross-linking and subsequent bacterial lysis.[1] However, their efficacy is notably weaker against enterococci due to the low affinity of cephalosporins for enterococcal PBPs, especially PBP5, which results in intrinsic resistance and limits clinical utility against these organisms.[50] In Gram-negative bacteria, cephalosporin activity is more variable and depends on penetration through the outer membrane via porin channels such as OmpF and OmpC, which allow access to periplasmic PBPs. Early cephalosporins demonstrate reliable coverage against common Enterobacterales like Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species by binding to their PBPs, but they generally lack activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa owing to poor porin penetration and intrinsic resistance mechanisms in this pathogen.[51][7] Cephalosporins have limited inherent activity against anaerobes, as many anaerobic species produce cephalosporinases that hydrolyze the beta-lactam ring, rendering the drugs ineffective against pathogens like Bacteroides fragilis. They also offer no coverage against atypical bacteria such as Mycoplasma or viruses, since these lack the peptidoglycan cell wall targeted by cephalosporins' mechanism of action.[52] Furthermore, susceptibility to beta-lactamases, including plasmid-mediated enzymes like TEM-1, significantly reduces cephalosporin efficacy by hydrolyzing the beta-lactam core, particularly in early variants, and contributes to widespread resistance among both Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens.[53]Pharmacokinetics

Absorption and Distribution

Cephalosporins exhibit variable oral absorption depending on the specific agent and generation, with first-generation compounds like cephalexin demonstrating high bioavailability of approximately 90-95% following oral administration.[54][55] This rapid absorption occurs primarily in the small intestine and is minimally affected by gastric pH or food intake, allowing cephalexin to be administered with or without meals due to its acid stability.[25] In contrast, some second- and third-generation oral cephalosporins, such as cefaclor or cefixime, show bioavailabilities ranging from 50-80%, with food potentially delaying the rate of absorption but not substantially reducing the extent.[56] Parenteral administration via intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) routes achieves complete bioavailability of 100%, bypassing gastrointestinal barriers and enabling rapid onset of action.[1] Once in the bloodstream, cephalosporins distribute primarily to extracellular fluids, including interstitial spaces in tissues such as lungs, kidneys, and soft tissues, due to their hydrophilic nature.[57] The volume of distribution is typically low, ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 L/kg across most agents, reflecting limited penetration into cells and adipose tissue.[58] Protein binding of cephalosporins varies widely from 5% to 90%, influencing the concentration of free, pharmacologically active drug available for distribution.[59] First-generation agents like cephalexin exhibit low binding (around 15%), promoting higher free fractions, while third-generation cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone show high binding (85-95%), which can prolong their half-life but may limit tissue availability.[60][61] Tissue penetration is generally good into synovial fluid, bile, and pleural spaces, but cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) access is poor under normal conditions (less than 5% penetration); however, in inflamed meninges during meningitis, third-generation agents like ceftriaxone achieve 15-30% CSF-to-serum ratios, enabling effective treatment.[4][62]Metabolism, Excretion, and Half-Life

Cephalosporins generally undergo minimal hepatic metabolism, with the majority of the administered dose excreted unchanged by the kidneys. This limited biotransformation contributes to their predictable pharmacokinetics and reduces the risk of active metabolites accumulating. Exceptions include certain third-generation agents like cefoperazone, which exhibits significant biliary excretion, accounting for about 70% of the dose depending on hepatic function, making it suitable for hepatobiliary infections.[63] The primary route of elimination for most cephalosporins is renal, involving both glomerular filtration and active tubular secretion. Typically, 60-90% of the unchanged drug is recovered in the urine within 6-24 hours post-administration, with variations across generations; for instance, first-generation agents like cephalexin achieve nearly 90% urinary recovery. In patients with normal renal function, this efficient clearance ensures rapid elimination, but dosage adjustments are necessary in chronic kidney disease (CKD) to prevent accumulation.[25][10] Half-lives of cephalosporins vary by generation and individual factors, generally ranging from 0.5 to 2 hours in patients with normal renal function, allowing for multiple daily dosing in most cases. For example, the first-generation cefazolin has a serum half-life of approximately 1.8 hours following intravenous administration. Fifth-generation agents like ceftaroline exhibit slightly prolonged half-lives of about 2.6 hours, supporting twice-daily regimens. Renal impairment significantly extends these durations; in anuric patients, ceftriaxone's half-life can increase to 11.4-15.7 hours, necessitating dose reductions in CKD stages 3-5 to maintain therapeutic levels without toxicity.[64][65][66][67]Classification

First-Generation Cephalosporins

First-generation cephalosporins represent the initial class of semisynthetic derivatives developed from the natural antibiotic cephalosporin C, featuring a core β-lactam ring fused to a dihydrothiazine ring with relatively simple modifications at the 7-acylamino side chain, such as phenylacetyl or tetrazolylacetyl groups, which confer their basic pharmacological properties.[68] These agents were introduced in the 1960s and 1970s, prioritizing activity against Gram-positive bacteria while offering modest expansion to select Gram-negatives compared to penicillins.[1] Prominent examples include cefazolin, an intravenous formulation commonly employed for surgical prophylaxis to prevent postoperative infections, and cephalexin, an oral agent frequently used for treating uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections such as cellulitis or impetigo.[1] Other notable drugs in this class are cephalothin, cephapirin, cephradine, and cefadroxil, which share similar structural simplicity and are administered via oral or parenteral routes depending on the clinical need.[1] Their straightforward acyl side chains, lacking the complex substitutions seen in later generations, contribute to favorable solubility and bioavailability profiles.[68] The antimicrobial spectrum of first-generation cephalosporins is narrow, with excellent activity against Gram-positive organisms including methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and various streptococci species, such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae.[1] Coverage against Gram-negative bacteria is limited to certain Enterobacterales, notably Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis, but extends minimally to Klebsiella pneumoniae in susceptible strains.[1] These drugs offer several advantages, including low cost, which makes them accessible for routine clinical use, and good tissue penetration into sites like skin, bone, and respiratory tract, enhancing their utility in targeted infections.[1] Additionally, they demonstrate stability against some staphylococcal beta-lactamases produced by S. aureus, allowing effective treatment of beta-lactamase-positive strains without the need for inhibitors.[1] Limitations include a lack of coverage against Pseudomonas species and anaerobic bacteria, restricting their application in polymicrobial or complex infections.[1] Typical minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for susceptible S. aureus are ≤2 μg/mL, underscoring their potency against targeted pathogens but highlighting vulnerability to resistance mechanisms like methicillin resistance.[69]Second-Generation Cephalosporins

Second-generation cephalosporins represent an advancement over first-generation agents by offering enhanced activity against certain Gram-negative bacteria and, in some cases, anaerobes, while maintaining good coverage of Gram-positive organisms. These antibiotics are particularly effective against pathogens such as Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, which are common in respiratory tract infections. Key examples include cefuroxime, available in both oral and intravenous formulations and commonly used for treating respiratory infections, and cefoxitin, an intravenous agent noted for its anaerobic activity.[1][36] The spectrum of activity for second-generation cephalosporins includes improved efficacy against Gram-negative aerobes like H. influenzae, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for cefuroxime typically ranging from 1 to 4 μg/mL against susceptible strains. Certain members also provide coverage against anaerobes, particularly through the cephamycin subclass, which targets Bacteroides species; for instance, cefoxitin demonstrates high activity against Bacteroides fragilis, inhibiting 82% of isolates at concentrations of 16 μg/mL or less. This expanded coverage makes them suitable for mixed infections involving both aerobes and anaerobes, such as intra-abdominal or pelvic infections.[70][71] Structurally, second-generation cephalosporins feature modifications at the 7-position of the beta-lactam ring that enhance resistance to beta-lactamases produced by some Gram-negative bacteria. In the cephamycin subclass, exemplified by cefoxitin and cefotetan, a 7-α-methoxy group is incorporated, which sterically hinders enzymatic hydrolysis and contributes to their stability against beta-lactamases. True cephalosporins in this generation, such as cefuroxime and cefprozil, lack this methoxy group but achieve similar resistance through alternative side-chain alterations. These subclasses—true cephalosporins versus cephamycins—distinguish variations in anaerobic potency, with cephamycins generally offering superior activity against Bacteroides spp.[72][73]Third-Generation Cephalosporins

Third-generation cephalosporins represent an advancement in the cephalosporin class, characterized by expanded activity against Gram-negative bacteria while retaining moderate efficacy against some Gram-positive organisms. These agents are particularly valued for treating serious infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae and Neisseria species, offering deeper penetration into Gram-negative pathogens compared to second-generation counterparts. Their design includes structural modifications, such as increased polarity at the 7-position side chain, which enhance outer membrane permeability in Gram-negative bacteria.[4] Prominent examples include ceftriaxone and cefotaxime, both of which exhibit long half-lives enabling convenient dosing regimens for central nervous system infections. Ceftriaxone, with a half-life of 6 to 9 hours, is administered once daily via intravenous route and is a mainstay for bacterial meningitis due to its excellent cerebrospinal fluid penetration.[74][75] Cefotaxime, featuring a half-life of approximately 1 hour but effective in divided doses, is similarly preferred for CNS infections like meningitis caused by susceptible pathogens.[76] Ceftazidime stands out among this generation for its specific utility against certain resistant strains, though the class generally shows reduced activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa except in this case.[77] The spectrum of activity emphasizes broad coverage of Gram-negative bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae) and Neisseria species (e.g., N. gonorrhoeae, N. meningitidis), with some preserved affinity for penicillin-binding proteins in Gram-positive cocci like Streptococcus pneumoniae, albeit diminished relative to first-generation agents. These drugs demonstrate high stability against many beta-lactamases produced by Gram-negative bacteria, conferring resistance to hydrolysis by common enzymes such as those from Haemophilus influenzae.[4][78] For instance, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ceftriaxone against susceptible N. gonorrhoeae strains is typically below 0.25 μg/mL, underscoring its potency in gonococcal infections.[79] In clinical practice, third-generation cephalosporins are often selected as preferred agents for empirical therapy of community-acquired infections, such as pneumonia or urinary tract infections, where Gram-negative pathogens predominate in outpatient or early hospital settings. This preference stems from their balanced profile against common community isolates, aiding timely intervention before culture results are available.[80][81]Fourth-Generation Cephalosporins

Fourth-generation cephalosporins represent an advancement in the cephalosporin class, characterized by their broad-spectrum activity that balances enhanced Gram-negative coverage with restored potency against Gram-positive bacteria, while offering improved stability against certain beta-lactamases. Key representatives include cefepime and cefpirome, both administered intravenously for serious infections such as febrile neutropenia in immunocompromised patients.[82] Cefepime, in particular, is frequently used as empirical therapy in hospital settings for its rapid bactericidal effects against pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[83] These agents feature zwitterionic structures, with a positively charged quaternary ammonium group on the acyl side chain that confers a net neutral charge, facilitating faster penetration through the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria compared to earlier generations.[84] This structural feature enhances their overall stability and efficacy in diverse clinical scenarios.[85] The spectrum of activity for fourth-generation cephalosporins encompasses a wide range of Gram-negative organisms, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae, alongside Gram-positive pathogens such as methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), staphylococci, and Streptococcus species.[86] This balanced profile arises from their ability to bind multiple penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), particularly PBP2 and PBP3 in Gram-negative bacteria, which restores Gram-positive activity diminished in third-generation agents while maintaining strong anti-Pseudomonal effects.[83] Cefpirome similarly demonstrates potent activity against Enterobacteriaceae, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa, making it suitable for moderate to severe nosocomial infections.[87] For instance, against P. aeruginosa, cefepime exhibits minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) typically ranging from 0.75 to 16 μg/mL, with an MIC90 of 8 μg/mL in clinical isolates, underscoring its utility in treating susceptible strains.[88] A primary advantage of fourth-generation cephalosporins is their resistance to hydrolysis by AmpC beta-lactamases, produced by certain Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas species, due to the zwitterionic configuration and side-chain modifications that reduce enzymatic degradation.[89] Cefepime, as a weak inducer of AmpC enzymes, withstands hydrolysis effectively, providing reliable activity against AmpC-derepressed strains where third-generation cephalosporins fail.[27] However, limitations include the absence of oral formulations, restricting their use to parenteral administration in hospital or outpatient infusion settings.[82] Additionally, emerging concerns with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing organisms have been noted, as some ESBL variants can hydrolyze these agents, potentially compromising efficacy in regions with high resistance prevalence.[90]Fifth-Generation Cephalosporins

Fifth-generation cephalosporins are a class of β-lactam antibiotics distinguished by their enhanced activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and certain multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, addressing gaps in coverage from prior generations.[1] These agents were developed to combat evolving bacterial resistance, with key representatives including ceftaroline, ceftobiprole, and cefiderocol, each approved by regulatory agencies between 2010 and 2024 for specific severe infections.[91] Their mechanism involves binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), including PBP2a in MRSA, which restores bactericidal activity against strains resistant to earlier cephalosporins.[92] Ceftaroline fosamil, the first fifth-generation cephalosporin approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010, is indicated for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) in adults and pediatric patients. It exhibits potent activity against Gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA and vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) typically ranging from 0.5 to 1 μg/mL for MRSA isolates.[93] Against Gram-negatives, ceftaroline covers common respiratory and skin pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis, but shows reduced efficacy against extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacterales and lacks reliable activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa or carbapenemase producers.[94] Administered intravenously, ceftaroline's prodrug form enhances solubility, allowing for once- or twice-daily dosing in clinical practice.[92] Ceftobiprole medocaril, approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2008 and by the FDA in April 2024 as Zevtera, expands treatment options for S. aureus bacteremia (SAB), including right-sided endocarditis, ABSSSI, and CABP in adults.[33] This intravenous agent demonstrates broad-spectrum coverage similar to ceftaroline, with strong anti-MRSA activity (FDA breakpoint ≤2 μg/mL for S. aureus) and efficacy against VISA, while also targeting Gram-negatives like Enterobacterales and some non-fermenters including P. aeruginosa.[95] In preclinical models of osteomyelitis, ceftobiprole cleared MRSA infections where MICs were ≤1 μg/mL, highlighting its bactericidal potential in deep-seated infections.[95] Unlike earlier cephalosporins, ceftobiprole's dual affinity for PBP2a and other PBPs enables its role in monotherapy for complicated infections previously requiring combination therapy.[96] Cefiderocol, approved by the FDA in 2019, represents a novel subclass of fifth-generation cephalosporins utilizing a siderophore cephalosporin mechanism to actively transport the drug into Gram-negative bacteria via iron uptake pathways, enhancing penetration in multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains. It is indicated for complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs) and hospital-acquired or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (HABP/VABP) caused by susceptible Gram-negatives, including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, Acinetobacter baumannii, and P. aeruginosa.[97] Cefiderocol's spectrum focuses on MDR Gram-negatives, with MIC90 values of 0.5–4 μg/mL for Enterobacterales, but it has limited Gram-positive coverage, including weaker activity against MRSA compared to ceftaroline or ceftobiprole.[98] This agent's stability against many β-lactamases, including metallo-β-lactamases, positions it as a key option for infections resistant to carbapenems, though it is reserved for cases where alternatives are unsuitable due to resistance patterns.[99]Naming Conventions and Comparative Table

Cephalosporins follow International Nonproprietary Name (INN) conventions established by the World Health Organization, employing the stem "cef-" to denote derivatives of 7-aminocephalosporanic acid used as systemic antibiotics.[100] Earlier first-generation agents, particularly oral formulations, may retain the "ceph-" prefix, as seen in cephalexin, while parenteral and later-generation drugs uniformly use "cef-".[101] Generation-specific naming patterns are not rigidly standardized but often provide mnemonic cues; for instance, third-generation cephalosporins frequently incorporate elements like "tri-" (e.g., ceftriaxone) or "tax-" (e.g., cefotaxime) to reflect their expanded spectrum.[1] These naming conventions facilitate identification of antimicrobial profiles, with generations broadly classified by evolving spectrum of activity, beta-lactamase resistance, and clinical applications. The following table compares the five generations, highlighting key examples, coverage against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (qualitatively based on typical minimum inhibitory concentrations, or MICs, where low MIC indicates good activity, e.g., ≤2 μg/mL for susceptible strains), stability to beta-lactamases (including extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, or ESBLs), and primary uses. Data are derived from established pharmacological reviews.[1][7]| Generation | Key Examples | Gram-Positive Coverage | Gram-Negative Coverage | Beta-Lactamase Stability | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Cefazolin, Cephalexin | Excellent (low MICs against MSSA, streptococci; e.g., MIC90 0.5–2 μg/mL for S. aureus) | Poor (high MICs against most Enterobacteriaceae; limited to some E. coli) | Low (hydrolyzed by penicillinases and early beta-lactamases) | Surgical prophylaxis, uncomplicated skin/soft tissue infections, urinary tract infections |

| Second | Cefuroxime, Cefoxitin | Good (moderate MICs against MSSA, streptococci; reduced vs. first generation) | Moderate (improved MICs against H. influenzae, Moraxella; e.g., MIC90 1–4 μg/mL for E. coli) | Moderate (resistant to some plasmid-mediated beta-lactamases; variable anaerobes) | Respiratory tract infections, intra-abdominal infections, gonorrhea |

| Third | Ceftriaxone, Cefotaxime | Fair (higher MICs against staphylococci; good for streptococci) | Excellent (low MICs against Enterobacteriaceae, Neisseria; e.g., MIC90 0.03–0.5 μg/mL for E. coli) | High against chromosomal beta-lactamases; low against ESBLs | Meningitis, serious Gram-negative infections, gonorrhea, Lyme disease |

| Fourth | Cefepime | Good (low-moderate MICs against MSSA, streptococci; restored vs. third) | Excellent (broad, including Pseudomonas; e.g., MIC90 0.5–8 μg/mL for P. aeruginosa) | High (stable to AmpC and extended-spectrum enzymes) | Febrile neutropenia, hospital-acquired pneumonia, intra-abdominal infections |

| Fifth | Ceftaroline | Excellent (low MICs against MRSA, streptococci; e.g., MIC90 0.5–1 μg/mL for MRSA) | Good (moderate MICs against Enterobacteriaceae; limited Pseudomonas) | High (resistant to ESBLs and MRSA-specific enzymes) | Community-acquired pneumonia, complicated skin infections (including MRSA) |