Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

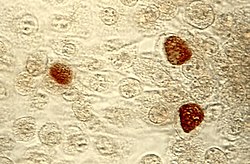

Chlamydia

View on Wikipedia

| Chlamydia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Chlamydia infection |

| |

| Pap smear showing C. trachomatis (H&E stain) | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, gynecology, urology |

| Symptoms | None, vaginal discharge, discharge from the penis, burning with urination[1] |

| Complications | Pain in the testicles, pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Few weeks following exposure[1] |

| Causes | Chlamydia trachomatis spread by sexual intercourse or childbirth[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Urine or swab of the cervix, vagina, or urethra[2] |

| Prevention | Not having sex, condoms, sex with only one non–infected person[1] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics (azithromycin or doxycycline)[2] |

| Frequency | 4.2% (women), 2.7% (men)[4][5] |

| Deaths | ~200 (2015)[6] |

Chlamydia, or more specifically a chlamydia infection, is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis.[3] Most people who are infected have no symptoms.[1] When symptoms do appear, they may occur only several weeks after infection;[1] the incubation period between exposure and being able to infect others is thought to be on the order of two to six weeks.[7] Symptoms in women may include vaginal discharge or burning with urination.[1] Symptoms in men may include discharge from the penis, burning with urination, or pain and swelling of one or both testicles.[1] The infection can spread to the upper genital tract in women, causing pelvic inflammatory disease, which may result in future infertility or ectopic pregnancy.[2]

Chlamydia infections can occur in other areas besides the genitals, including the anus, eyes, throat, and lymph nodes. Repeated chlamydia infections of the eyes that go without treatment can result in trachoma, a common cause of blindness in the developing world.[8]

Chlamydia can be spread during vaginal, anal, oral, or manual sex and can be passed from an infected mother to her baby during childbirth.[1][9] The eye infections may also be spread by personal contact, flies, and contaminated towels in areas with poor sanitation.[8] Infection by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis only occurs in humans.[10] Diagnosis is often by screening, which is recommended yearly in sexually active women under the age of 25, others at higher risk, and at the first prenatal visit.[1][2] Testing can be done on the urine or a swab of the cervix, vagina, or urethra.[2] Rectal or mouth swabs are required to diagnose infections in those areas.[2]

Prevention is by not having sex, the use of condoms, or having sex with only one other person, who is not infected.[1] Chlamydia can be cured by antibiotics, with typically either azithromycin or doxycycline being used.[2] Erythromycin or azithromycin is recommended in babies and during pregnancy.[2] Sexual partners should also be treated, and infected people should be advised not to have sex for seven days and until symptom free.[2] Gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV should be tested for in those who have been infected.[2] Following treatment, people should be tested again after three months.[2]

Chlamydia is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, affecting about 4.2% of women and 2.7% of men worldwide.[4][5] In 2015, about 61 million new cases occurred globally.[11] In the United States, about 1.4 million cases were reported in 2014.[3] Infections are most common among those between the ages of 15 and 25 and are more common in women than men.[2][3] In 2015, infections resulted in about 200 deaths.[6] The word chlamydia is from the Greek χλαμύδα, meaning 'cloak'.[12][13]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Genital disease

[edit]

Women

[edit]Chlamydial infection of the cervix (neck of the womb) is a sexually transmitted infection which has no symptoms for around 70% of women infected. The infection can be passed through vaginal, anal, oral, or manual sex. Of those who have an asymptomatic infection that is not detected by their doctor, approximately half will develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), a generic term for infection of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and/or ovaries. PID can cause scarring inside the reproductive organs, which can later cause serious complications, including chronic pelvic pain, difficulty becoming pregnant, ectopic (tubal) pregnancy, and other dangerous complications of pregnancy.[14]

Chlamydia is known as the "silent epidemic", as at least 70% of genital C. trachomatis infections in women (and 50% in men) are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis,[15] and can linger for months or years before being discovered. Signs and symptoms may include abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge, abdominal pain, painful sexual intercourse, fever, painful urination or the urge to urinate more often than usual (urinary urgency).[14]

For sexually active women who are not pregnant, screening is recommended in those under 25 and others at risk of infection.[16] Risk factors include a history of chlamydial or other sexually transmitted infection, new or multiple sexual partners, and inconsistent condom use.[17] Guidelines recommend all women attending for emergency contraceptive are offered chlamydia testing, with studies showing up to 9% of women aged under 25 years had chlamydia.[18]

Men

[edit]In men, those with a chlamydial infection show symptoms of infectious inflammation of the urethra in about 50% of cases.[15] Symptoms that may occur include: a painful or burning sensation when urinating, an unusual discharge from the penis, testicular pain or swelling, or fever. If left untreated, chlamydia in men can spread to the testicles causing epididymitis, which in rare cases can lead to sterility if not treated.[15] Chlamydia is also a potential cause of prostatic inflammation in men, although the exact relevance in prostatitis is difficult to ascertain due to possible contamination from urethritis.[19]

Eye disease

[edit]

Trachoma is a chronic conjunctivitis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis.[20] It was once the leading cause of blindness worldwide, but its role diminished from 15% of blindness cases by trachoma in 1995 to 3.6% in 2002.[21][22] The infection can be spread from eye to eye by fingers, shared towels or cloths, coughing and sneezing and eye-seeking flies.[23] Symptoms include mucopurulent ocular discharge, irritation, redness, and lid swelling.[20] Newborns can also develop chlamydia eye infection through childbirth (see below). Using the SAFE strategy (acronym for surgery for in-growing or in-turned lashes, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvements), the World Health Organization aimed (unsuccessfully) for the global elimination of trachoma by 2020 (GET 2020 initiative).[24][25] The updated World Health Assembly neglected tropical diseases road map (2021–2030) sets 2030 as the new timeline for global elimination.[26]

Joints

[edit]Chlamydia may also cause reactive arthritis—the triad of arthritis, conjunctivitis and urethral inflammation—especially in young men. About 15,000 men develop reactive arthritis due to chlamydia infection each year in the U.S., and about 5,000 are permanently affected by it. It can occur in both sexes, though is more common in men.[citation needed]

Infants

[edit]As many as half of all infants born to mothers with chlamydia will be born with the disease. Chlamydia can affect infants by causing spontaneous abortion; premature birth; conjunctivitis, which may lead to blindness; and pneumonia.[27] Conjunctivitis due to chlamydia typically occurs one week after birth (compared with chemical causes (within hours) or gonorrhea (2–5 days)).[28]

Other conditions

[edit]A different serovar of Chlamydia trachomatis is also the cause of lymphogranuloma venereum, an infection of the lymph nodes and lymphatics. It usually presents with genital ulceration and swollen lymph nodes in the groin, but it may also manifest as rectal inflammation, fever or swollen lymph nodes in other regions of the body.[29]

Transmission

[edit]Chlamydia can be transmitted during vaginal, anal, oral, or manual sex or direct contact with infected tissue such as conjunctiva. Chlamydia can also be passed from an infected mother to her baby during vaginal childbirth.[27] It is assumed that the probability of becoming infected is proportionate to the number of bacteria one is exposed to.[30]

Recent research using droplet digital PCR and viability assays found evidence of high-viability C. trachomatis in the gastrointestinal tract of women who abstained from receptive anal intercourse. Rectal C. trachomatis appeared independent of cervical infection—with distinct MLST types detected in rectal versus endocervical samples—suggesting persistent gastrointestinal colonization likely acquired through prior vaginorectal or oral routes, rather than direct anal exposure.[31]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Chlamydia bacteria have the ability to establish long-term associations with host cells. When an infected host cell is starved for various nutrients such as amino acids (for example, tryptophan),[32] iron, or vitamins, this has a negative consequence for chlamydia bacteria since the organism is dependent on the host cell for these nutrients. Long-term cohort studies indicate that approximately 50% of those infected clear within a year, 80% within two years, and 90% within three years.[33]

The starved chlamydia bacteria can enter a persistent growth state where they stop cell division and become morphologically aberrant by increasing in size.[34] Persistent organisms remain viable as they are capable of returning to a normal growth state once conditions in the host cell improve.[35]

There is debate as to whether persistence has relevance: some believe that persistent chlamydia bacteria are the cause of chronic chlamydial diseases. Some antibiotics such as β-lactams have been found to induce a persistent-like growth state.[36][37]

Diagnosis

[edit]

The diagnosis of genital chlamydial infections evolved rapidly from the 1990s through 2006. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), transcription mediated amplification (TMA), and the DNA strand displacement amplification (SDA) now are the mainstays. NAAT for chlamydia may be performed on swab specimens sampled from the cervix (women) or urethra (men), on self-collected vaginal swabs, or on voided urine.[38] NAAT has been estimated to have a sensitivity of approximately 90% and a specificity of approximately 99%, regardless of sampling from a cervical swab or by urine specimen.[39] In women seeking treatment in a sexually transmitted infection clinic where a urine test is negative, a subsequent cervical swab has been estimated to be positive in approximately 2% of the time.[39]

At present, the NAATs have regulatory approval only for testing urogenital specimens, although rapidly evolving research indicates that they may give reliable results on rectal specimens.

Because of improved test accuracy, ease of specimen management, convenience in specimen management, and ease of screening sexually active men and women, the NAATs have largely replaced culture, the historic gold standard for chlamydia diagnosis, and the non-amplified probe tests. The latter test is relatively insensitive, successfully detecting only 60–80% of infections in asymptomatic women, and often giving falsely-positive results. Culture remains useful in selected circumstances and is currently the only assay approved for testing non-genital specimens. Other methods also exist including: ligase chain reaction (LCR), direct fluorescent antibody resting, enzyme immunoassay, and cell culture.[40]

The swab sample for chlamydial infections does not show difference whether the sample was collected in home or in clinic in terms of numbers of patient treated. The implications in cured patients, reinfection, partner management, and safety are unknown.[41]

Rapid point-of-care tests are, as of 2020, not thought to be effective for diagnosing chlamydia in men of reproductive age and non-pregnant women because of high false-negative rates.[42]

Prevention

[edit]Prevention is by not having sex, the use of condoms, or having sex only in a long-term monogamous relationship with someone who has been tested and confirmed not to be infected.[1]

Screening

[edit]For sexually active women who are not pregnant, screening is recommended in those under 25 and others at risk of infection.[16] Risk factors include a history of chlamydial or other sexually transmitted infection, new or multiple sexual partners, and inconsistent condom use.[17] For pregnant women, guidelines vary: screening women with age or other risk factors is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (which recommends screening women under 25) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (which recommends screening women aged 25 or younger). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all at risk, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend universal screening of pregnant women.[16] The USPSTF acknowledges that in some communities there may be other risk factors for infection, such as ethnicity.[16] Evidence-based recommendations for screening initiation, intervals and termination are currently not possible.[16] For men, the USPSTF concludes evidence is currently insufficient to determine if regular screening of men for chlamydia is beneficial.[17] They recommend regular screening of men who are at increased risk for HIV or syphilis infection.[17] A Cochrane review found that the effects of screening are uncertain in terms of chlamydia transmission but that screening probably reduces the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease in women.[43]

In the United Kingdom the National Health Service (NHS) aims to:

- Prevent and control chlamydia infection through early detection and treatment of asymptomatic infection;

- Reduce onward transmission to sexual partners;

- Prevent the consequences of untreated infection;

- Test at least 25 percent of the sexually active under 25 population annually.[44]

- Retest after treatment.[45]

Treatment

[edit]C. trachomatis infection can be effectively cured with antibiotics. Guidelines recommend azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, levofloxacin, or ofloxacin.[46] In men, doxycycline (100 mg twice a day for 7 days) is probably more effective than azithromycin (1 g single dose) but evidence for the relative effectiveness of antibiotics in women is very uncertain.[47] Agents recommended during pregnancy include erythromycin or amoxicillin.[2][48]

An option for treating sexual partners of those with chlamydia or gonorrhea includes patient-delivered partner therapy (PDT or PDPT), which is the practice of treating the sex partners of index cases by providing prescriptions or medications to the patient to take to his/her partner without the health care provider first examining the partner.[49]

Following treatment people should be tested again after three months to check for reinfection.[2] Test of cure may be false-positive due to the limitations of NAAT in a bacterial (rather than a viral) context, since targeted genetic material may persist in the absence of viable organisms.[50]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Globally, as of 2015, sexually transmitted chlamydia affects approximately 61 million people.[11] It is more common in women (3.8%) than men (2.5%).[52] In 2015 it resulted in about 200 deaths.[6]

In the United States about 1.6 million cases were reported in 2016.[53] The CDC estimates that if one includes unreported cases there are about 2.9 million each year.[53] It affects around 2% of young people.[54] Chlamydial infection is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the UK.[55]

Chlamydia causes more than 250,000 cases of epididymitis in the U.S. each year. Chlamydia causes 250,000 to 500,000 cases of PID every year in the United States. Women infected with chlamydia are up to five times more likely to become infected with HIV, if exposed.[27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Chlamydia – CDC Fact Sheet". CDC. May 19, 2016. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines". CDC. June 4, 2015. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "2014 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance Chlamydia". November 17, 2015. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b Newman L, Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, et al. (8 December 2015). "Global Estimates of the Prevalence and Incidence of Four Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections in 2012 Based on Systematic Review and Global Reporting". PLOS ONE. 10 (12) e0143304. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1043304N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. PMC 4672879. PMID 26646541.

- ^ a b "Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) Fact sheet N°110". who.int. December 2015. Archived from the original on 25 November 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Shors T (2018). Krasner's Microbial Challenge. p. 366.

- ^ a b "CDC – Trachoma, Hygiene-related Diseases, Healthy Water". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 28, 2009. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ^ Hoyle A, McGeeney E (2019). Great Relationships and Sex Education. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-1-35118-825-8. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Graeter L (2014). Elsevier's Medical Laboratory Science Examination Review. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-323-29241-2. Archived from the original on 2017-09-10.

- ^ a b Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Stevenson A (2010). Oxford dictionary of English (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Byrne GI (July 2003). "Chlamydia uncloaked". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (14): 8040–8042. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.8040B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1533181100. PMC 166176. PMID 12835422.

The term was coined based on the incorrect conclusion that Chlamydia are intracellular protozoan pathogens that appear to cloak the nucleus of infected cells.

- ^ a b Witkin SS, Minis E, Athanasiou A, Leizer J, Linhares IM (October 2017). "Chlamydia trachomatis: the Persistent Pathogen". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 24 (10). doi:10.1128/CVI.00203-17. PMC 5629669. PMID 28835360.

- ^ a b c NHS Chlamydia page Archived 2013-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Meyers D, Wolff T, Gregory K, Marion L, Moyer V, Nelson H, et al. (March 2008). "USPSTF recommendations for STI screening". American Family Physician. 77 (6): 819–824. PMID 18386598. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ^ a b c d U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (July 2007). "Screening for chlamydial infection: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (2): 128–134. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00172. PMID 17576996. S2CID 35816540. Archived from the original on 2008-03-03.

- ^ Yeung EY, Comben E, McGarry C, Warrington R (February 2015). "STI testing in emergency contraceptive consultations". The British Journal of General Practice. 65 (631): 63.1–64. doi:10.3399/bjgp15X683449. PMC 4325454. PMID 25624285.

- ^ Wagenlehner FM, Naber KG, Weidner W (April 2006). "Chlamydial infections and prostatitis in men". BJU International. 97 (4): 687–690. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06007.x. PMID 16536754. S2CID 34481915.

- ^ a b Lewis SM (2017). Medical-surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems. Bucher, Linda; Heitkemper, Margaret M. (Margaret McLean); Harding, Mariann (10th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri. ISBN 978-0-323-32852-4. OCLC 944472408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thylefors B, Négrel AD, Pararajasegaram R, Dadzie KY (1995). "Global data on blindness" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 73 (1): 115–121. PMC 2486591. PMID 7704921. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25.

- ^ Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya'ale D, Kocur I, Pararajasegaram R, Pokharel GP, et al. (November 2004). "Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82 (11): 844–851. hdl:10665/269277. PMC 2623053. PMID 15640920.

- ^ Mabey DC, Solomon AW, Foster A (July 2003). "Trachoma". Lancet. 362 (9379): 223–229. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13914-1. PMID 12885486. S2CID 208789262.

- ^ World Health Organization. Trachoma Archived 2012-10-21 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed March 17, 2008.

- ^ Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Matthews F, Reacher M, Brayne C, Baba S, et al. (August 2006). "Effect of 3 years of SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental change) strategy for trachoma control in southern Sudan: a cross-sectional study". Lancet. 368 (9535): 589–595. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69202-7. PMID 16905023. S2CID 45018412.

- ^ "Trachoma". www.who.int. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ a b c "STD Facts – Chlamydia". Center For Disease Control. December 16, 2014. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ^ Hansford P (April 2010), "Palliative Care in the United Kingdom", Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing, Oxford University Press, pp. 1265–1274, doi:10.1093/med/9780195391343.003.0072, ISBN 978-0-19-539134-3

- ^ Williams D, Churchill D (January 2006). "Ulcerative proctitis in men who have sex with men: an emerging outbreak". BMJ. 332 (7533): 99–100. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7533.99. PMC 1326936. PMID 16410585.

- ^ Gambhir M, Basáñez MG, Turner F, Kumaresan J, Grassly NC (June 2007). "Trachoma: transmission, infection, and control". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 7 (6): 420–427. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70137-8. PMID 17521595.

- ^ Karlsson PA, Wänn M, Wang H, Falk L, Herrmann B (2025-01-10). "Highly viable gastrointestinal Chlamydia trachomatis in women abstaining from receptive anal intercourse". Scientific Reports. 15 (1) 1641. Bibcode:2025NatSR..15.1641K. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-85297-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 11724036. PMID 39794438.

- ^ Leonhardt RM, Lee SJ, Kavathas PB, Cresswell P (November 2007). "Severe tryptophan starvation blocks onset of conventional persistence and reduces reactivation of Chlamydia trachomatis". Infection and Immunity. 75 (11): 5105–5117. doi:10.1128/IAI.00668-07. PMC 2168275. PMID 17724071.

- ^ Fairley CK, Gurrin L, Walker J, Hocking JS (September 2007). ""Doctor, how long has my Chlamydia been there?" Answer: ".... years"". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 34 (9): 727–728. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31812dfb6e. PMID 17717486.

- ^ Mpiga P, Ravaoarinoro M (2006). "Chlamydia trachomatis persistence: an update". Microbiological Research. 161 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2005.04.004. PMID 16338585.

- ^ Kushwaha AK (2020-07-26). Textbook of Microbiology. Dr. A.K KUSHWAHA.

- ^ Bayramova F, Jacquier N, Greub G (2018). "Insight in the biology of Chlamydia-related bacteria". Microbes and Infection. 20 (7–8). Elsevier: 432–440. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2017.11.008. PMID 29269129.

- ^ Klöckner A, Bühl H, Viollier P, Henrichfreise B (2018). "Deconstructing the Chlamydial Cell Wall". In Häcker, Georg (ed.). Biology of Chlamydia. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 412. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–33. doi:10.1007/82_2016_34. ISBN 978-3-319-71232-1. PMID 27726004.

- ^ Gaydos CA, Theodore M, Dalesio N, Wood BJ, Quinn TC (July 2004). "Comparison of three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in urine specimens". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 42 (7): 3041–3045. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.7713. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.7.3041-3045.2004. PMC 446239. PMID 15243057.

- ^ a b Haugland S, Thune T, Fosse B, Wentzel-Larsen T, Hjelmevoll SO, Myrmel H (March 2010). "Comparing urine samples and cervical swabs for Chlamydia testing in a female population by means of Strand Displacement Assay (SDA)". BMC Women's Health. 10 (1) 9. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-10-9. PMC 2861009. PMID 20338058.

- ^ "Recommendations for the Laboratory-Based Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae — 2014". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 2016-06-27. Retrieved 2016-06-12.

- ^ Fajardo-Bernal L, Aponte-Gonzalez J, Vigil P, Angel-Müller E, Rincon C, Gaitán HG, et al. (Cochrane STI Group) (September 2015). "Home-based versus clinic-based specimen collection in the management of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (9) CD011317. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011317.pub2. PMC 8666088. PMID 26418128.

- ^ Grillo-Ardila CF, Torres M, Gaitán HG (January 2020). "Rapid point of care test for detecting urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in nonpregnant women and men at reproductive age". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD011708. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011708.pub2. PMC 6988850. PMID 31995238.

- ^ Low N, Redmond S, Uusküla A, van Bergen J, Ward H, Andersen B, et al. (September 2016). "Screening for genital chlamydia infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (9) CD010866. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010866.pub2. PMC 6457643. PMID 27623210.

- ^ "National Chlamydia Screening Programme Data tables". www.chlamydiascreening.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-05-04. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ^ Desai M, Woodhall SC, Nardone A, Burns F, Mercey D, Gilson R (August 2015). "Active recall to increase HIV and STI testing: a systematic review". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 91 (5): 314–323. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2014-051930. PMID 25759476.

Strategies for improved follow up care include the use of text messages and emails from those who provided treatment.

- ^ Eliopoulos GM, Gilbert DN, Moellering RC, eds. (2015). The Sanford guide to antimicrobial therapy 2011. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc. pp. 20. ISBN 978-1-930808-65-2.

- ^ Páez-Canro C, Alzate JP, González LM, Rubio-Romero JA, Lethaby A, Gaitán HG (January 2019). "Antibiotics for treating urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection in men and non-pregnant women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD010871. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010871.pub2. PMC 6353232. PMID 30682211.

- ^ Miller KE (April 2006). "Diagnosis and treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection". American Family Physician. 73 (8): 1411–1416. PMID 16669564. Archived from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ Expedited Partner Therapy in the Management of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (2 February 2006) Archived 29 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention

- ^ Dukers-Muijrers N, Morré S, Speksnijder A, Sande M, Hoebe C (28 March 2012). "Chlamydia trachomatis Test-of-Cure Cannot Be Based on a Single Highly Sensitive Laboratory Test Taken at Least 3 Weeks after Treatment". PLOS ONE. 7 (3) e34108. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...734108D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034108. PMC 3314698. PMID 22470526.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2004. Archived from the original on 2009-11-11. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- ^ Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–2196. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607.

- ^ a b "Detailed STD Facts – Chlamydia". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Torrone E, Papp J, Weinstock H (September 2014). "Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection among persons aged 14-39 years--United States, 2007-2012". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 63 (38): 834–838. PMC 4584673. PMID 25254560.

- ^ "Chlamydia". UK Health Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.