Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Flippase

View on Wikipedia

Flippases are transmembrane lipid transporter proteins located in the cell membrane. They are responsible for aiding the movement of phospholipid molecules between the two layers, or leaflets, that comprise the membrane. This is called transverse diffusion, also known as "flip-flop" transition. Flippases move lipids to the cytosolic layer, usually from the extracellular layer. Floppases do the opposite, moving lipids to the extracellular layer. Both flippases and floppases are powered by ATP hydrolysis and are either P4-ATPases or ATP-Binding Cassette transporters. Scramblases are energy-independent and transport lipids in both directions.[1][2][3]

Lateral and transverse movements

[edit]In organisms, the cell membrane consists of a phospholipid bilayer. Phospholipid molecules are movable in the bilayer. These movements are categorized into two types: lateral movements and transverse movements (also called flip-flop). The first is the lateral movement, where the phospholipid moves horizontally on the same side of the membrane. Lateral movement is fast, with an average speed of up to 2 mm per second.[4] Transverse movement is the movement of the phospholipid molecule from one side of the membrane to the other. Transverse movement without the assistance of enzymes is slow, occurring once a month.[4] This is because the polar head groups of phospholipid molecule cannot easily pass through the hydrophobic center of the bilayer, limiting their diffusion in this dimension.

Although flip-flop is slow, this movement is necessary to continue the cell's normal function of growth and mobility.[5] The possibility of active maintenance of the asymmetric distribution of molecules in the phospholipid bilayer was predicted in the early 1970s by Mark Bretscher.[6] Lipid asymmetry has broad physiological implications, from cell shape determination to critical signaling processes like blood coagulation and apoptosis.[7] Many cells maintain asymmetric distributions of phospholipids between their cytoplasmic and exoplasmic membrane leaflets. The loss of asymmetry, in particular the appearance of the anionic phospholipid phosphatidylserine on the exoplasmic face, can serve as an early indicator of apoptosis[8] and as a signal for efferocytosis.[9]

Different classes of lipid transporters

[edit]Lipid transporters transport lipids across the bilayers. There exist three major classes of lipid transporters:

- P-type Flippase

- ABC Floppase

- Scramblases

P-type Flippase and ABC Floppase are energy-dependent enzymes that can create lipid asymmetry and transport specific lipids. Scramblases are energy-independent enzymes that can dissipate lipid asymmetry and have broad lipid specificity.[11]

Structure and domains of P4-type flippases

[edit]

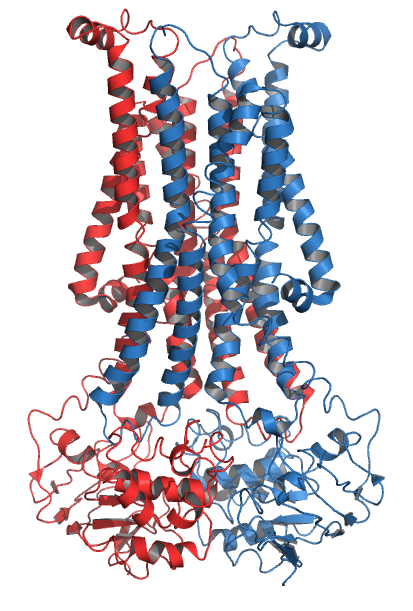

The P4-type flippase contains a large transmembrane segment and two major subunits, a catalytic domain called the alpha-subunit and an accessory domain named the beta-subunit.[5] Transmembrane segments contain 10 transmembrane alpha helices and this domain together with the beta-subunit plays an important role in the stability, localization, and recognition of the lipid substrate of flippase.[5] Alpha-subunits include A, P, and N domains and each of them corresponds to a different function of flippase. The A-domain is an actuator segment of flippase that facilitates phospholipid binding through conformational change of the complex, although it does not bind the phospholipid itself. The P-domain is responsible for binding phosphate, a product of ATP hydrolysis. The next domain is the N-domain, whose job is to bind the substrate (ATP).[5] Finally, a C-terminal autoregulatory domain has been identified, whose function differs between yeast and mammalian P4-type flippases.[12]

Mechanism of P4-type flippases

[edit]

To bind specific lipid on the outer layer of membrane, P4-type flippase needs to be phosphorylated by ATP on its P-domain. After ATP hydrolysis and phosphorylation, P4-type flippases undergo conformational change from E1 to E2 (E1 and E2 stand for different conformations of flippases).[5] Further conformational change is induced by the binding of a phospholipid, resulting in the E2Pi.PL conformation.[12] The flippase in its E2 conformation can then be dephosphorylated at its P-domain, allowing the lipid to be transported to the inner layer of membrane, where it diffuses away from the flippase. As the phospholipid dissociates from the complex, a conformational change on flippase occurs from E2 back to E1 readying it for the next cycle of lipid transportation.[5]

The A-domain binds to the N-domain after that domain releases ADP. The A-domain can bind to the N-domain by a TGES four-amino-acid motif when the P-domain is phosphorylated. The release of ADP from the N-domain transitions the complex from the E1P-ADP state to the E2P state, which might be further stabilized by binding of the C-terminal regulatory domain. Binding of a phospholipid to the first two transmembrane segments induces a conformational change that rotates the A domain outward by 22 degrees, allowing dephosphorylation of the P domain. Dephosphorylation of the P-domain is energetically coupled to translocation of the polar phospholipid head across the membrane leaflets.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Maxfield, Frederick R.; Menon, Anant K. (2016), "Intramembrane and Intermembrane Lipid Transport", Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes, Elsevier, pp. 415–436, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63438-2.00014-6, ISBN 978-0-444-63438-2

- ^ Graham, Todd R. (20 July 2021). "Tour de flippase". ASMBM Today. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- ^ Andersen, Jens P.; Vestergaard, Anna L.; Mikkelsen, Stine A.; Mogensen, Louise S.; Chalat, Madhavan; Molday, Robert S. (2016-07-08). "P4-ATPases as Phospholipid Flippases—Structure, Function, and Enigmas". Frontiers in Physiology. 7. doi:10.3389/fphys.2016.00275. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 4937031. PMID 27458383.

- ^ a b Pace, R. J.; Chan, Sunney I. (1982-04-15). "Molecular motions in lipid bilayers. III. Lateral and transverse diffusion in bilayers". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 76 (8): 4241–4247. Bibcode:1982JChPh..76.4241P. doi:10.1063/1.443501. ISSN 0021-9606.

- ^ a b c d e f Nagata, Shigekazu; Sakuragi, Takaharu; Segawa, Katsumori (February 2020). "Flippase and scramblase for phosphatidylserine exposure". Current Opinion in Immunology. 62: 31–38. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2019.11.009. PMID 31837595.

- ^ Bretscher, Mark S. (March 1972). "Asymmetrical Lipid Bilayer Structure for Biological Membranes". Nature New Biology. 236 (61): 11–12. doi:10.1038/newbio236011a0. ISSN 0090-0028. PMID 4502419.

- ^ Clarke, R.J.; Hossain, K.R.; Cao, K. (October 2020). "Physiological roles of transverse lipid asymmetry of animal membranes". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1862 (10) 183382. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183382. PMID 32511979.

- ^ Castegna, Alessandra; Lauderback, Christopher M; Mohmmad-Abdul, Hafiz; Butterfield, D.Allan (April 2004). "Modulation of phospholipid asymmetry in synaptosomal membranes by the lipid peroxidation products, 4-hydroxynonenal and acrolein: implications for Alzheimer's disease". Brain Research. 1004 (1–2): 193–197. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.036. PMID 15033435.

- ^ Nagata, Shigekazu; Segawa, Katsumori (February 2021). "Sensing and clearance of apoptotic cells". Current Opinion in Immunology. 68: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2020.07.007. PMID 32853880.

- ^ Sharom, Frances J. (2011). "Flipping and flopping-lipids on the move". IUBMB Life. 63 (9): 736–746. doi:10.1002/iub.515. PMID 21793163.

- ^ Hankins, Hannah M.; Baldridge, Ryan D.; Xu, Peng; Graham, Todd R. (January 2015). "Role of Flippases, Scramblases and Transfer Proteins in Phosphatidylserine Subcellular Distribution". Traffic. 16 (1): 35–47. doi:10.1111/tra.12233. ISSN 1398-9219. PMC 4275391. PMID 25284293.

- ^ a b c Hiraizumi M, Yamashita K, Nishizawa T, Nureki O (2019). "Cryo-EM structures capture the transport cycle of the P4-ATPase flippase". Science. 365 (6458): 1149–1155. Bibcode:2019Sci...365.1149H. doi:10.1126/science.aay3353. PMID 31416931.