Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

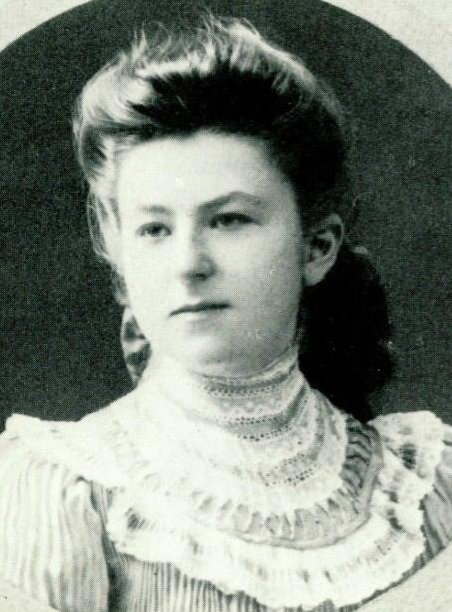

Flora Solomon

View on Wikipedia

Flora Solomon, OBE (née Benenson; 28 September 1895 – 18 July 1984)[1] was an influential Zionist.[2] The first woman hired to improve working conditions at Marks & Spencer in London,[3] Solomon was later instrumental in the exposure of British spy Kim Philby.[4] She was the mother of Peter Benenson, founder of Amnesty International. She described her "personal trinity" as "Russian soul, Jewish heart, British passport".[4]

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Flora Benenson was born on 28 September 1895 in Pinsk, in what is now Belarus. She was a daughter of Sophie Goldberg and the Jewish Russian financier Grigori Benenson, who was related to the Rothschild family. She had three siblings: an older brother, Jacob ("Yasha") who was interned in Germany during World War I and subsequently died of Spanish flu,[5] and two sisters--Fira Benenson (Countess Ilinska), who became a leading American dress designer, and Manya Harari, who became a noted translator of Russian literature.[6] The family's fortune was based on gold and oil; they settled in Britain in 1914, and lost much of their wealth as a result of the Russian Revolution in 1917.[4][7]

Career

[edit]In the 1930s, prior to World War II, Solomon helped find homes for refugee children who fled to London from continental Europe.[8] During World War II she organised food distribution for the British government and was awarded the OBE for her work.

Marks and Spencer

[edit]Solomon is also remembered for improving employee conditions at Marks & Spencer stores in the UK.[9]

In 1939, over dinner with Simon Marks, the son of a founder of Marks & Spencer, she complained to him about the company's salary policies. She learned that staff often did not eat lunch because they could not afford it. She said to Marks, "It's firms like Marks & Spencer that give Jews a bad name". Marks immediately gave Solomon the job of looking after staff welfare.[10]

In her new position, she "pioneered the development of the staff welfare system" (including subsidised medical services). These practices directly influenced the Labour concept of the welfare state and the creation of the British National Health Service in 1948. As a result, Marks & Spencer acquired the reputation of the "working man's paradise".[11]

Publishing

[edit]She founded Blackmore Press, a British printing house. Her life was described in her autobiography A Woman's Way, written in collaboration with Barnet Litvinoff and published in 1984 by Simon & Schuster. The work was also titled Baku to Baker Street: The Memoirs of Flora Solomon.

Kim Philby

[edit]Solomon was a long-time friend of British intelligence officer Kim Philby. She introduced him to his second wife Aileen, whom she knew from her work as a store detective at Marks and Spencers.[12] In 1937, while working in Spain as The Times correspondent on Franco's side of the Civil War, Philby proposed to Solomon that she might become a Soviet agent. His friend from Cambridge, Guy Burgess, was simultaneously trying to recruit her into MI6. But the Soviet resident in Paris, Ozolin-Haskin (code-name Pierre) rejected this as a provocation. Had both moves succeeded she would have become a double agent.[13]

In 1962 when Philby was the correspondent of the London Observer in Beirut, she objected to the anti-Israeli tone of his articles. She related the details of the 1937 contact to Victor Rothschild, who had worked for MI5 during the Second World War. In August 1962, during a reception at the Weizmann Institute, Solomon told Rothschild that she thought that Tomás Harris and Philby were Soviet spies.[14] She then went on to tell Rothschild that she suspected that Philby and Harris had been Soviet agents since the 1930s. "Those two were so close as to give me an intuitive feeling that Harris was more than a friend."[15] Solomon was then interviewed by MI5 officers and recounted Philby's attempt to recruit her in 1937, after he told her he was "doing important work for peace" and that "you should be doing it too."[4]

Soviet defector Anatoliy Golitsyn had already told the CIA about Philby's work for the KGB up to 1949. Nicholas Elliott, a former MI6 colleague of Philby's in Beirut, confronted him. Prompted by Elliott's accusations, Philby confirmed the charges of espionage and described his intelligence activities on behalf of the Soviets. However, when Elliott asked him to sign a written statement, he hesitated and requested a delay in the interrogation.[16] A week later he boarded a Soviet freighter the Dolmatova bound for Odessa, en route to Moscow, never to return.[17]

Before Harris was interviewed by MI5, he was killed in a motor accident at Lluchmayor, Majorca. Some people have suggested that Harris was murdered.[18] Chapman Pincher, the author of Their Trade is Treachery (1981), agrees that it is possible that Harris had been eliminated by the KGB: "The police could find nothing wrong with the car, which hit a tree, but Harris's wife, who survived the crash, could not explain why the vehicle had gone into a sudden slide. It is considered possible, albeit remotely, that the KGB might have wanted to silence Harris before he could talk to the British security authorities, as he was an expansive personality, when in the mood, and was outside British jurisdiction. The information, about which MI5 wanted to question him and would be approaching him in Majorca, could have leaked to the KGB from its source inside MI5."[19] Pincher goes onto argue that the source was probably Roger Hollis, the director-general of MI5.

Personal life

[edit]Flora Benenson was married to Harold Solomon, a member of a London stockbroking family and a career soldier who was a brigadier-general in the First World War. They had one child, Peter Benenson, who would become the founder of Amnesty International.[8]

She was widowed in 1930 and raised Peter on her own.

Flora Solomon died on 18 July 1984.[1]

Works

[edit]- Solomon, Flora; Litvinoff, Barry (1984). A Woman's Way. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-46002-0. (also titled Baku to Baker Street: The Memoirs of Flora Solomon)

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "Mrs Flora Solomon: Russian émigré of wide interests". The Times. London, England. 25 August 1984. p. 10.

- ^ Hopgood, Stephen (2006). Keepers of the Flame: Understanding Amnesty International. Cornell University Press. pp. 272 pages. ISBN 0-8014-7251-2.

- ^ Gall, Susan B. (1997). Women's Firsts. Gale Research. pp. 564 pages. ISBN 0-7876-0151-9.

- ^ a b c d "The woman who exposed Britain's most infamous double-agent". www.thejc.com. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Solomon & Litvinoff (1984), pp. 66, 91.

- ^ "GRIGORI BENENSON, NOTED FINANCIER; Former Owner of Building at 165 Broadway Succumbs to Stroke in London WON FORTUNE IN BAKU OIL Founder of English-Russian Bank in St. Petersburg--Had Developed Gold Properties". The New York Times. 6 April 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "Harari [née Benenson], Manya (1905–1969), publisher and translator". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33688. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 27 March 2022. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b "Peter Benenson hero file". Heroes & killers of the 20th century. moreorless.au.com. 11 March 2005. Archived from the original on 20 January 2008.

- ^ Smith, Gerald Stanton (2000). D.S. Mirsky: A Russian-English Life, 1890-1939. Oxford University Press. pp. 424 pages. ISBN 0-19-816006-2.

- ^ Seth, Andrew; Randall, Geoffrey (1999). The Grocers: The Rise and Rise of the Supermarket Chains. Kogan Page. pp. 331 pages. ISBN 0-7494-2191-6. p. 120

- ^ Rogatchevski, Andrei (3 August 2007). "Marks, Not Marx: The Case of Marks & Spencer". Cultural Studies Panel -- The East in the West: Imports into European Mass Culture. Berlin, Germany: ICCEES Regional European Congress. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben (4 April 2014). "My hero: Flora Solomon by Ben Macintyre". the Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Borovik, Genrikh (1994). The Philby Files: The Secret Life of Master Spy Kim Philby. New York: Little Brown. ISBN 0-316-10284-9.

- ^ Biography of Flora Solomon

- ^ Solomon & Litvinoff (1984), p. 226.

- ^ Carver, Tom (11 October 2012). "Diary: Philby in Beirut". London Review of Books. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ West, Nigel; Tsarev, Oleg (1999). The Crown Jewels: The British Secrets at the Heart of the KGB Archives. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07806-4.

- ^ Biography of Tomás Harris

- ^ Chapman Pincher, Their Trade is Treachery (1981) pages 169–170

References

[edit]- Solomon, Flora; Litvinoff, Barry (1984). A Woman's Way. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-46002-0.