Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spanish flu

View on Wikipedia

| Spanish flu | |

|---|---|

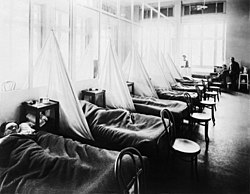

Soldiers sick with Spanish flu at a hospital ward at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas | |

| Disease | Influenza |

| Virus strain | Strains of A/H1N1 |

| Location | Worldwide |

| Index case | Haskell County, Kansas January 1918[a] |

| Date | February 1918 – April 1920[2] |

| Suspected cases‡ | 500 million (estimated)[3] |

Deaths | 25–50 million (generally accepted), other estimates range from 17 to 100 million[4][5][6] |

| ‡Suspected cases have not been confirmed by laboratory tests as being due to this strain, although some other strains may have been ruled out. | |

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was March 1918 in Haskell County, Kansas, United States, with further cases recorded in France, Germany and the United Kingdom in April. Two years later, nearly a third of the global population, or an estimated 500 million people, had been infected. Estimates of deaths range from 17 million to 50 million,[7][8] and possibly as high as 100 million,[9] making it the deadliest pandemic in history.

The pandemic broke out near the end of World War I, when wartime censors in the belligerent countries suppressed bad news to maintain morale, but newspapers freely reported the outbreak in neutral Spain, creating a false impression of Spain as the epicenter and leading to the "Spanish flu" misnomer.[10] Limited historical epidemiological data make the pandemic's geographic origin indeterminate, with competing hypotheses on the initial spread.[3]

Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the young and old, but this pandemic had unusually high mortality for young adults.[11] Scientists offer several explanations for the high mortality, including a six-year climate anomaly affecting migration of disease vectors with increased likelihood of spread through bodies of water.[12] However, the claim that young adults had a high mortality during the pandemic has been contested.[13] Malnourishment, overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, and poor hygiene, exacerbated by the war, promoted bacterial superinfection, killing most of the victims after a typically prolonged death bed.[14][15]

Etymologies

[edit]

This pandemic was known by many different names depending on place, time, and context. The etymology of alternative names historicises the scourge and its effects on people who would only learn years later that viruses caused influenza.[16] The lack of scientific answers led the Sierra Leone Weekly News (Freetown) to suggest a biblical framing in July 1918, using an interrogative from Exodus 16 in ancient Hebrew:[b] "One thing is for certain—the doctors are at present flabbergasted; and we suggest that rather than calling the disease influenza they should for the present until they have it in hand, say Man hu—'What is it?'"[18][19][20]

Descriptive names

[edit]Outbreaks of influenza-like illness were documented in 1916–17 at British military hospitals in Étaples, France,[21] and just across the English Channel at Aldershot, England. Clinical indications in common with the 1918 pandemic included rapid symptom progression to a "dusky" heliotrope face. This characteristic blue-violet cyanosis in expiring patients led to the name 'purple death'.[22][23][24]

The Aldershot physicians later wrote in The Lancet, "the influenza pneumococcal purulent bronchitis we and others described in 1916 and 1917 is fundamentally the same condition as the influenza of this present pandemic."[25] This "purulent bronchitis" is not yet linked to the same A/H1N1 virus,[26] but it may be a precursor.[25][27][28]

In 1918, 'epidemic influenza',[29] also known at the time as 'the grip' (French: la grippe, grasp),[30] appeared in Kansas, U.S., during late spring, and early reports from Spain began appearing on 21 May.[31][32] Reports from both places called it 'three-day fever'.[33][34][35]

Associative names

[edit]Many alternative names are exonyms in the practice of making new infectious diseases seem foreign.[36][37][38] This pattern was observed even before the 1889–1890 pandemic, also known as the 'Russian flu', when the Russians already called epidemic influenza the 'Chinese catarrh', the Germans called it the 'Russian pest', and the Italians called it the 'German disease'.[39][40] These epithets were re-used in the 1918 pandemic, along with new ones.[41]

'Spanish' influenza

[edit]

Outside Spain, the disease was soon misnamed 'Spanish influenza'.[42][43] In a 2 June 1918 The Times of London dispatch titled, "The Spanish Epidemic," a correspondent in Madrid reported over 100,000 victims of, "The unknown disease...clearly of a gripal character," without referring to "Spanish influenza" directly.[44] Three weeks later The Times reported that, "Everybody thinks of it as the 'Spanish' influenza to-day."[45] Three days after that an advertisement appeared in The Times for Formamint tablets to prevent "Spanish influenza".[46][47] When it reached Moscow, Pravda announced, "Ispánka (the Spanish lady) is in town," making 'the Spanish lady' another common name.[48]

The outbreak did not originate in Spain,[49] but reporting did, due to wartime censorship in belligerent nations. Spain was a neutral country unconcerned with appearances of combat readiness, and without a wartime propaganda machine to prop up morale,[50][51] so its newspapers freely reported epidemic effects, making Spain the apparent locus of the epidemic.[52] The censorship was so effective that Spain's health officials were unaware its neighboring countries were similarly affected.[53] In an October 1918 "Madrid Letter" to the Journal of the American Medical Association, a Spanish official protested, "we were surprised to learn that the disease was making ravages in other countries, and that people there were calling it the 'Spanish grip'. And wherefore Spanish? ...this epidemic was not born in Spain, and this should be recorded as a historic vindication."[54]

Other exonyms

[edit]French press initially used 'American flu', but adopted 'Spanish flu' in lieu of antagonizing an ally.[55] In the spring of 1918, British soldiers called it 'Flanders flu', while German soldiers used 'Flandern-Fieber' (Flemish fever), both after a battlefield in Belgium where many soldiers on both sides fell ill.[41][38][56][57] In Senegal it was named 'Brazilian flu', and in Brazil, 'German flu'.[58] In Spain it was also known as the 'French flu' (gripe francesa),[49][10] or the 'Naples Soldier' (Soldado de Nápoles), after a popular song from a zarzuela.[c][55] Spanish flu (gripe española) is now a common name in Spain,[60] but remains controversial there.[61][62]

Othering derived from geopolitical borders and social boundaries.[63][64] In Poland it was the 'Bolshevik disease',[58][65] while in Russia it was referred to it as the 'Kirghiz disease'.[57] Some Africans called it a 'white man's sickness', but in South Africa, white men also used the ethnophaulism 'kaffersiekte' (lit. 'negro disease').[41][66] Japan blamed sumo wrestlers for bringing the disease home from Taiwan, calling it 'sumo flu' (Sumo Kaze).[67][68]

World Health Organization 'best practices' first published in 2015 now aim to prevent social stigma by not associating culturally significant names with new diseases, listing "Spanish flu" under "examples to be avoided".[69][37][70] Many authors now eschew calling this the Spanish flu,[55] instead using variations of '1918–19/20 flu/influenza pandemic'.[71][72][73]

Local names

[edit]Some language endonyms did not name specific regions or groups of people. Examples specific to this pandemic include: Northern Ndebele: 'Malibuzwe' (let enquiries be made concerning it), Swahili: 'Ugonjo huo kichwa na kukohoa na kiuno' (the disease of head and coughing and spine),[74] Yao: 'chipindupindu' (disease from seeking to make a profit in wartime), Otjiherero: 'kaapitohanga' (disease which passes through like a bullet),[75] and Persian: nakhushi-yi bad (disease of the wind).[76][77]

Other names

[edit]This outbreak was also commonly known as the 'great influenza epidemic',[78][79] after the 'great war', a common name for World War I before World War II.[80] French military doctors originally called it 'disease 11' (maladie onze).[38] German doctors downplayed the severity by calling it 'pseudo influenza' (Greek: pseudo, false), while in Africa, doctors tried to get patients to take it more seriously by calling it 'influenza vera' (Latin: vera, true).[81]

A children's song from the 1889–90 flu pandemic[82] was shortened and adapted into a skipping-rope rhyme popular in 1918.[83][84] It is a metaphor for the transmissibility of 'Influenza', where that name was clipped to 'Enza':[85][86][87]

I had a little bird,

its name was Enza.

I opened the window,

and in-flu-enza.

History

[edit]Potential origins

[edit]Despite its name, historical and epidemiological data cannot identify the geographic origin of the Spanish flu.[3] However, several theories have been proposed.

United States

[edit]The first confirmed cases originated in the United States. Historian Alfred W. Crosby stated in 2003 that the flu originated in Kansas,[88] and author John M. Barry described a January 1918 outbreak in Haskell County, Kansas, as the origin in his 2004 article.[80]

A 2018 study of tissue slides and medical reports led by professor Michael Worobey found evidence against the disease originating from Kansas, as those cases were milder and had fewer deaths compared to the infections in New York City in the same period. The study did find evidence through phylogenetic analyses that the virus likely had a North American origin, though it was not conclusive. In addition, the haemagglutinin glycoproteins of the virus suggest that it originated long before 1918, and other studies suggest that the reassortment of the H1N1 virus likely occurred in or around 1915.[89]

Europe

[edit]

The major UK troop staging and hospital camp in Étaples in France has been theorized by virologist John Oxford as being at the center of the Spanish flu.[1] His study found that in late 1916 the Étaples camp was hit by a new disease with high mortality that caused symptoms similar to the flu.[90][1] According to Oxford, a similar outbreak occurred in March 1917 at army barracks in Aldershot,[91] and military pathologists later recognized these early outbreaks as the same disease as the Spanish flu.[92][1]

The overcrowded camp and hospital at Étaples was an ideal environment for the spread of a respiratory virus. The hospital treated thousands of victims of poison gas attacks, and other casualties of war. It also was home to a piggery, and poultry was regularly brought in to feed the camp. Oxford and his team postulated that a precursor virus, harbored in birds, mutated and then migrated to pigs kept near the front.[91][92] A report published in 2016 in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association found evidence that the 1918 virus had been circulating in the European armies for months and possibly years before the 1918 pandemic.[93] Political scientist Andrew Price-Smith published data from the Austrian archives suggesting the influenza began in Austria in early 1917.[94]

A 2009 study in Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses found that Spanish flu mortality simultaneously peaked within the two-month period of October and November 1918 in all fourteen European countries analyzed, which is inconsistent with the pattern that researchers would expect if the virus had originated somewhere in Europe and then spread outwards.[95]

China

[edit]In 1993, Claude Hannoun, the leading expert on the Spanish flu at the Pasteur Institute, asserted the precursor virus was likely to have come from China and then mutated in the United States near Boston and from there spread to Brest, France, Europe's battlefields, and the rest of the world, with Allied forces as the main disseminators.[96] Hannoun considered several alternative hypotheses of origin, such as Spain, Kansas, and Brest, as being possible, but not likely.[96]

In 2014, historian Mark Humphries of the Memorial University of Newfoundland argued that the mobilization of 96,000 Chinese laborers to work behind the British and French lines might have been the source of the pandemic. Humphries found archival evidence that a respiratory illness that struck northern China (where the laborers came from) in November 1917 was identified a year later by Chinese health officials as identical to the Spanish flu.[97][98] No tissue samples have survived for modern comparison.[99] Nevertheless, there were some reports of respiratory illness on the path the laborers took to get to Europe, which also passed through North America.[99]

China was one of the few regions of the world seemingly less affected by the Spanish flu pandemic, where several studies have documented a comparatively mild flu season in 1918.[100][101][102] (This is disputed due to lack of data during the Warlord Period.) This has led to speculation that the Spanish flu pandemic originated in China,[102][103] as the lower mortality rates may be explained by the Chinese population's previously acquired immunity to the flu virus.[104][102] In the Guangdong Province it was reported that early outbreaks of influenza in 1918 disproportionately impacted young men. The June outbreak infected children and adolescents between 11 and 20 years of age, while the October outbreak was most common in those aged 11 to 15.[102]

A report published in 2016 in the Journal of the Chinese Medical Association found no evidence that the 1918 virus was imported to Europe via Chinese and Southeast Asian soldiers and workers and instead found evidence of its circulation in Europe before the pandemic.[93] The 2016 study found that the low flu mortality rate (an estimated one in a thousand) recorded among the Chinese and Southeast Asian workers in Europe suggests that the Asian units were not different from other Allied military units in France at the end of 1918 and, thus not a likely source of a new lethal virus.[93] Further evidence against the disease being spread by Chinese workers was that workers entered Europe through other routes that did not result in a detectable spread, making them unlikely to have been the original hosts.[89]

Timeline

[edit]First wave of early 1918

[edit]

The pandemic is conventionally marked as having begun on 4 March 1918 with the recording of the case of Albert Gitchell, an army cook at Camp Funston in Kansas despite there having been cases before him.[106] The disease had already been observed 200 miles (320 km) away in Haskell County as early as January 1918, prompting local doctor Loring Miner to warn the editors of the U.S. Public Health Service's journal Public Health Reports.[80] Within days of the 4 March case at Camp Funston, 522 men at the camp had reported sick.[107] By 11 March 1918, the virus had reached Queens, New York.[108] Failure to take preventive measures in March/April was later criticized.[109]

As the U.S. had entered World War I, the disease quickly spread from Camp Funston, a major training ground for troops of the American Expeditionary Forces, to other U.S. Army camps and Europe, becoming an epidemic in the Midwest, East Coast, and French ports by April 1918, and reaching the Western Front by mid-April.[106] It then quickly spread to the rest of France, Great Britain, Italy, and Spain and in May reached Wrocław and Odessa.[106] After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918), Germany started releasing Russian prisoners of war, who brought the disease to their country.[110] It reached North Africa, India, and Japan in May, and soon after had likely gone around the world as there had been recorded cases in Southeast Asia in April.[111] In June an outbreak was reported in China.[112] After reaching Australia in July, the wave started to recede.[111]

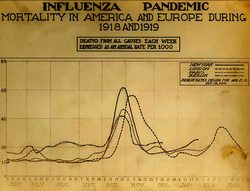

The first wave lasted from the first quarter of 1918 and was relatively mild.[113] Mortality rates were not appreciably above normal; in the United States ~75,000 flu-related deaths were reported in the first six months of 1918, compared to ~63,000 deaths during the same time period in 1915.[3][114] In Madrid, Spain, fewer than 1,000 people died from influenza between May and June 1918.[115] There were no reported quarantines; the first wave caused a significant disruption in the military operations of World War I, with three-quarters of French troops, half the British forces, and over 900,000 German soldiers sick.[116]

Deadly second wave of late 1918

[edit]

The second wave began in the second half of August 1918, probably spreading to Boston, Massachusetts and Freetown, Sierra Leone, by ships from Brest, where it had likely arrived with American troops or French recruits for naval training.[116] From the Boston Navy Yard and Camp Devens, about 30 miles (48 km) west of Boston, other U.S. military sites were soon afflicted, as were troops being transported to Europe.[117] Helped by troop movements, it spread over the next two months to all of North America, and then to Central and South America, also reaching Brazil and the Caribbean on ships.[118] In July 1918, the Ottoman Empire saw its first cases, in soldiers.[119] From Freetown, the pandemic spread through West Africa along the coast, rivers, and railways, and from railheads to more remote communities, while South Africa received it in September on ships bringing back members of the South African Native Labour Corps from France.[118] From there it spread around southern Africa and beyond the Zambezi, reaching Ethiopia in November.[120] On 15 September, New York City saw its first fatality from influenza.[121] The Philadelphia Liberty Loans Parade, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 28 September 1918 to promote government bonds for World War I, resulted in an outbreak causing 12,000 deaths.[122]

From Europe, the second wave swept through Russia in a southwest–northeast diagonal front, as well as being brought to Arkhangelsk by the North Russia intervention, and then spread throughout Asia following the Russian Civil War and the Trans-Siberian railway, reaching Iran (where it spread through Mashhad), and then India in September and China and Japan in October.[123] The celebrations of the Armistice of 11 November 1918 also caused outbreaks in Lima and Nairobi, but by December the wave was mostly over.[124]

The second wave of the 1918 pandemic was much more deadly than the first. The first wave had resembled typical flu epidemics; those most at risk were the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people recovered easily. October 1918 was the month with the highest fatality rate of the whole pandemic.[125] In the United States, ~292,000 deaths were reported between September–December 1918, compared to ~26,000 during the same time period in 1915.[114] The Netherlands reported over 40,000 deaths from influenza and acute respiratory disease. Bombay reported ~15,000 deaths in a population of 1.1 million.[126] The 1918 flu pandemic in India was especially deadly, as Historian David Arnold estimates at least 12 million dead, about 5% of the population.[127]

Third wave of 1919

[edit]

Pandemic activity persisted into 1919 in many places, possibly attributable to climate, specifically in the Northern Hemisphere, where it was winter and thus the usual time for influenza activity.[128][129] The pandemic nonetheless continued into 1919 largely independent of region and climate.[128]

Cases began to rise again in some parts of the U.S. as early as late November 1918,[130] with the Public Health Service issuing its first report of a "recrudescence of the disease" in "widely scattered localities" in early December.[131] This resurgent activity varied across the country, however, possibly on account of differing restrictions.[129] Michigan, for example, experienced a swift resurgence of influenza that reached its peak in December, possibly as a result of the lifting of the ban on public gatherings.[132] Pandemic interventions, such as bans on public gatherings and the closing of schools, were reimposed in many places in an attempt to suppress the spread.[131]

There was "a very sudden and very marked rise in general death rate" in most cities in January 1919; nearly all experienced "some degree of recrudescence" of the flu in January and February.[133]: 153–154 Significant outbreaks occurred in cities including Los Angeles,[134] New York City,[2] Memphis, Nashville, San Francisco,[135] and St. Louis.[136] By 21 February, with some local variation, influenza activity was reported to have been declining since mid-January in all parts of the country.[137] Following this "first great epidemic period" that had commenced in October 1918, deaths from pneumonia and influenza were "somewhat below average" in large U.S. cities between May 1919 and January 1920.[133]: 158 Nonetheless, nearly 160,000 deaths were attributed to these causes in the first six months of 1919.[138]

It was not until later in the winter and into the spring that a clearer resurgence appeared in Europe. A significant third wave had developed in England and Wales by mid-February, peaking in early March, though it did not fully subside until May.[139] France also experienced a significant wave that peaked in February, alongside the Netherlands. Norway, Finland, and Switzerland saw recrudescences of pandemic activity in March, and Sweden in April.[95]

Much of Spain was affected by "a substantial recrudescent wave" of influenza between January and April 1919.[140] Portugal experienced a resurgence in pandemic activity that lasted from March to September 1919, with the greatest impact being felt on the west coast and in the north of the country; all districts were affected between April and May specifically.[141]

Influenza entered Australia for the first time in January 1919 after a strict maritime quarantine had shielded the country through 1918.[142] It assumed epidemic proportions first in Melbourne, peaking in mid-February.[143] The flu soon appeared in neighboring New South Wales and South Australia.[142] New South Wales experienced its first wave of infection between mid-March and late May,[144] while a second, more severe wave occurred in Victoria between April and June.[143] Land quarantine measures hindered the spread of the disease. Queensland was not infected until late April; Western Australia avoided the disease until early June, and Tasmania remained free from it until mid-August.[142] Out of the six states, Victoria and New South Wales experienced generally more extensive epidemics. Each experienced another significant wave of illness over the winter. The second epidemic in New South Wales was more severe than the first,[144] while Victoria saw a third wave that was somewhat less extensive than its second, more akin to its first.[143]

The disease also reached other parts of the world for the first time in 1919, such as Madagascar, which saw its first cases in April; the outbreak had spread to practically all sections of the island by June.[145] In other parts, influenza recurred in the form of a true "third wave". Hong Kong experienced another outbreak in June,[146] as did South Africa during its fall and winter months in the Southern Hemisphere.[147][148][149] New Zealand experienced some cases in May.[150]

Parts of South America experienced a resurgence of pandemic activity throughout 1919. A third wave hit Brazil between January and June.[128] Between July 1919 and February 1920, Chile, which had been affected for the first time in October 1918, experienced a severe second wave, with mortality peaking in August 1919.[151] Montevideo similarly experienced a second outbreak between July and September.[152]

The third wave particularly affected Spain, Serbia, Mexico and Great Britain, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths.[153]

Fourth wave of 1920

[edit]

In the Northern Hemisphere, fears of a "recurrence" of the flu grew as fall approached. Experts cited past flu epidemics, such as that of 1889–1890, to predict that such a recurrence a year later was not unlikely,[154][155] though not all agreed.[156] In September 1919, U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue said a return of the flu later in the year would "probably, but by no means certainly," occur.[157] France had readied a public information campaign before the end of the summer,[158] and Britain began preparations in the autumn with the manufacture of vaccine.[159]

In Japan, the flu broke out again in December and spread rapidly throughout the country, a fact attributed at the time to cold weather.[160][161] Pandemic-related measures were renewed to check the outbreak, and health authorities recommended the use of masks.[161] The epidemic intensified in the latter part of December before swiftly peaking in January.[162]

Between October 1919 and 23 January 1920, 780,000 cases were reported across the country, with at least 20,000 deaths recorded by that date. This apparently reflected "a condition of severity three times greater than for the corresponding period of" 1918–1919.[162] Nonetheless, the disease was regarded as being milder than it had been the year before, albeit more infectious.[163] Despite its rapid peak at the beginning of the year, the outbreak persisted throughout the winter, before subsiding in the spring.[164]

In the United States, there were "almost continuously isolated or solitary cases" of flu throughout the spring and summer of 1919.[165] An increase in scattered cases became apparent as early as September,[166] but Chicago experienced one of the first major outbreaks of the flu beginning in the middle of January.[167] The Public Health Service announced it would take steps to "localize the epidemic",[168] but the disease was already causing a simultaneous outbreak in Kansas City and quickly spread outward from the center of the country.[165] A few days after its first announcement, PHS issued another assuring that the disease was under the control of state health authorities and that an outbreak of epidemic proportions was not expected.[169]

It became apparent within days of the start of Chicago's explosive growth in cases that the flu was spreading in the city at an even faster rate than in winter 1919, though fewer were dying.[170] Within a week, new cases in the city had surpassed its peak during the 1919 wave.[171] Around the same time, New York City began to see its own sudden increase in cases,[172] and other cities around the country were soon to follow.[173] Certain pandemic restrictions, such as the closing of schools and theaters and the staggering of business hours to avoid congestion, were reimposed in cities like Chicago,[174] Memphis,[175] and New York City.[176] As they had during the epidemic in fall 1918, schools in New York City remained open,[176] while those in Memphis were shuttered as part of restrictions on public gatherings.[175]

The fourth wave in the United States subsided as swiftly as it had appeared, reaching a peak in early February.[177] "An epidemic of considerable proportions marked the early months of 1920", the U.S. Mortality Statistics would later note; according to data at this time, the epidemic resulted in one third as many deaths as the 1918–1919 experience.[178] New York City alone reported 6,374 deaths between December 1919 and April 1920, almost twice the number of the first wave in spring 1918.[2] Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Minneapolis, and St. Louis were hit particularly hard, with death rates higher than all of 1918.[136] Hawaii experienced its peak of the pandemic in early 1920, recording 1,489 deaths from flu-related causes, compared with 615 in 1918 and 796 in 1919.[179]

Poland experienced a devastating outbreak during the winter months, with its capital Warsaw reaching a peak of 158 deaths in a single week, compared to the peak of 92 in December 1918; however, the 1920 epidemic passed in a matter of weeks, while the 1918–1919 wave had developed over the entire second half of 1918.[180] By contrast, the outbreak in western Europe was considered "benign", with the age distribution of deaths beginning to take on that of seasonal flu.[115] Spain, Denmark, Finland, Germany and Switzerland recorded a late peak between January–April 1920.[95]

Mexico experienced a fourth wave between February and March. In South America, Peru experienced "asynchronous recrudescent waves" throughout the year. A severe third wave hit Lima, the capital city, between January and March, resulting in an all-cause excess mortality rate approximately four times greater than that of the 1918–1919 wave. Ica similarly experienced another severe pandemic wave in 1920, between July and October.[181] A fourth wave also occurred in Brazil, in February.[128]

Korea and Taiwan experienced pronounced outbreaks in late 1919 and early 1920.[182][183]

Post-pandemic

[edit]By mid-1920, the pandemic was largely considered to be "over" by the public as well as governments.[184] Though parts of Chile experienced a third, milder wave between November 1920 and March 1921,[151] the flu seemed to be mostly absent through the winter of 1920–1921.[133]: 167 In the United States, for example, deaths from pneumonia and influenza were "very much lower than for many years".[133]: 167

Seasonal influenza began to be reported again from many places in 1921.[133]: 168 Influenza continued to be felt in Chile, where a post-pandemic fourth wave affected 7 of its 24 provinces between June and December 1921.[151] The winter of 1921–1922 was the first major reappearance of seasonal influenza in the Northern Hemisphere, in many parts its most significant occurrence since the main pandemic in late 1918. Northwestern Europe was particularly affected. All-cause mortality in the Netherlands approximately doubled in January 1922 alone.[133]: 168 In Helsinki, a major epidemic (the fifth since 1918) prevailed between November and December 1921.[185] The flu was also widespread in the United States, its prevalence in California reportedly greater in early March 1922 than at any point since the pandemic ended in 1920.[133]: 172

In the years after 1920, the disease came to represent the "seasonal flu". The virus, H1N1, remained endemic, occasionally causing more severe or otherwise notable outbreaks.[186] The period since its initial appearance in 1918 has been termed a "pandemic era", in which all flu pandemics have been caused by its own descendants.[187] Following the first of these post-1918 pandemics, in 1957, the virus was totally displaced by the novel H2N2, the reassortant product of the human H1N1 and an avian influenza virus, which thereafter became the active influenza A virus in humans.[186]

In 1977, an influenza virus bearing a very close resemblance to the seasonal H1N1, which had not been seen since the 1950s, appeared in Russia and subsequently initiated a "technical" pandemic that principally affected those 26 and under.[188][189] While some natural explanations, such as the virus remaining in some frozen state for 20 years,[189] have been proposed to explain this unprecedented[190] phenomenon, the nature of influenza itself has been cited in favor of human involvement of some kind, such as an accidental leak from a lab where the old virus had been preserved for research purposes.[189] Following this miniature pandemic, the reemerged H1N1 became endemic again but did not displace the other active influenza A virus, H3N2 (which itself had displaced H2N2 through a pandemic in 1968).[188][186] For the first time, two influenza A viruses were observed in cocirculation.[104] This state has persisted even after 2009, when a novel H1N1 virus emerged, sparked a pandemic, and thereafter took the place of the seasonal H1N1 to circulate alongside H3N2.[104]

Epidemiology and pathology

[edit]Transmission and mutation

[edit]

The basic reproduction number of the virus was between 2 and 3.[191] The close quarters and massive troop movements of World War I hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and augmented mutation. The war may also have reduced people's resistance to the virus. Some speculate the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by malnourishment and the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility.[192][193] Modern transportation systems and increased travel was a significant factor in the worldwide occurrence.[194] Another was lies and denial by governments, leaving the population ill-prepared to handle the outbreaks.[195]

The severity of the second wave has been attributed to the First World War.[196] In civilian life, natural selection favors a mild strain. Those who get very ill stay home, and those mildly ill continue with their lives, preferentially spreading the mild strain. In the trenches, natural selection was reversed. Soldiers with a mild strain stayed where they were, while the severely ill were sent on crowded trains to crowded field hospitals, spreading the deadlier virus. The second wave began, and the flu quickly spread around the world again. (During modern pandemics, health officials look for deadlier strains of a virus when it reaches places with social upheaval.[197]) The fact that most of those who recovered from first-wave infections had become immune showed that it must have been the same strain of flu. This was most dramatically illustrated in Copenhagen, which escaped with a combined mortality rate of 0.29% (0.02% in the first wave and 0.27% in the second wave) because of exposure to the less-lethal first wave.[198]

After the lethal second wave, new cases dropped abruptly. In Philadelphia, for example, 4,597 people died in the week ending 16 October, but by 11 November, influenza had almost disappeared from the city. One explanation for the rapid decline in lethality is that doctors became more effective in the prevention and treatment of pneumonia that developed after the victims had contracted the virus. However, John Barry stated in his 2004 book The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague In History that researchers have found no evidence to support this position.[80] Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to a less lethal strain. Such evolution of influenza is a common occurrence: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to die out.[80] Fatal cases did continue into 1919, however. One notable example was that of ice hockey player Joe Hall, who died of the flu in April after an outbreak that resulted in the cancellation of the 1919 Stanley Cup Finals.[199]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

The majority of the infected experienced only the typical flu symptoms of sore throat, headache, and fever, especially during the first wave.[200] However, during the second wave, the disease was much more serious, often complicated by bacterial pneumonia, which was often the cause of death.[200] This more serious type would cause heliotrope cyanosis to develop, whereby the skin would first develop two mahogany spots over the cheekbones which would then over a few hours color the entire face blue, followed by black coloration first in the extremities and then the limbs and the torso.[200] Death would follow within hours or days due to the lungs being filled with fluids.[200] Other signs and symptoms reported included spontaneous mouth and nosebleeds, miscarriages for pregnant women, a peculiar smell, teeth and hair falling out, delirium, dizziness, insomnia, loss of hearing or smell, and impaired vision.[200] One observer wrote, "One of the most striking of the complications was hemorrhage from mucous membranes, especially from the nose, stomach, and intestine. Bleeding from the ears and petechial hemorrhages in the skin also occurred".[201]

The majority of deaths were from bacterial pneumonia,[202][203][204] a common secondary infection associated with influenza. This pneumonia was itself caused by common upper respiratory-tract bacteria, which were able to get into the lungs via the damaged bronchial tubes.[205] The virus also killed people directly by causing massive hemorrhages and edema in the lungs.[204] Modern analysis has shown the virus to be particularly deadly because in animal trials it triggers an overreaction of the body's immune system (cytokine storm).[80] The strong immune reactions of young adults were postulated to have ravaged the body, whereas the weaker immune reactions of children and middle-aged adults resulted in fewer deaths.[206]

Misdiagnosis

[edit]Because the virus that caused the disease was too small to be seen under a microscope at the time, there were problems with correctly diagnosing it.[207] The bacterium Haemophilus influenzae was instead mistakenly thought to be the cause, as it was big enough to be seen and was present in many, though not all, patients.[207] For this reason, a vaccine that was used against that bacillus did not make infection rarer but did decrease the death rate.[208]

During the deadly second wave there were also fears that it was in fact plague, dengue fever, or cholera.[209] Another misdiagnosis was typhus, which was common in circumstances of social upheaval, and was therefore also affecting Russia in the aftermath of the October Revolution.[209] In Chile, the view of the country's elite was that the nation was in severe decline, and therefore doctors assumed that the disease was typhus caused by poor hygiene, causing a mismanaged response which did not ban mass gatherings.[209]

Role of climate conditions

[edit]

Studies have shown that the immune system of Spanish flu victims could have been weakened by unseasonably cold and wet weather for extended periods during the pandemic. This affected especially troops exposed to incessant rains and lower-than-average temperatures during World War I, and especially during the second wave of the pandemic. Climate data and mortality records analyzed at Harvard University and the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine identified a severe climate anomaly that impacted Europe from 1914 to 1919, with several environmental indicators directly influencing the severity and spread of the pandemic.[12] Specifically, a significant increase in precipitation affected all of Europe during the second wave of the pandemic, from September to December 1918. Mortality figures follow closely the concurrent increase in precipitation and decrease in temperatures. Several explanations have been proposed for this, including that lower temperatures and increased precipitation provided ideal conditions for virus replication and transmission, while also negatively affecting peoples' immune systems, a factor proven to increase likelihood of infection by both viruses and pneumococcal co-morbid infections documented to have affected a large percentage of pandemic victims (one fifth of them, with a 36% mortality rate).[210][211][212][213][214] The climate anomaly likely influenced the migration of H1N1 avian vectors which contaminate bodies of water with their droppings, reaching 60% infection rates in autumn.[215][216][217] The climate anomaly has been associated with an anthropogenic increase in atmospheric dust, due to the incessant bombardment; increased nucleation due to dust particles (cloud condensation nuclei) contributed to increased precipitation.[218][219][220]

Responses

[edit]Public health management

[edit]While systems for alerting public health authorities of infectious spread did exist in 1918, they did not generally include influenza, leading to a delayed response.[223] Nevertheless, actions were taken. Maritime quarantines were declared on islands such as Iceland, Australia, and American Samoa, saving many lives.[223] Social distancing measures were introduced, for example closing schools, theatres, and places of worship, limiting public transportation, and banning mass gatherings.[224] Wearing face masks became common in some places, such as Japan, though there were debates over their efficacy.[224][225] There was also some resistance to their use, as exemplified by the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco. Vaccines were developed, but as these were based on bacteria and not the actual virus, they could only help with secondary infections.[224] The enforcement of restrictions varied.[226] To a large extent, the New York City health commissioner ordered businesses to open and close on staggered shifts to avoid overcrowding on the subways.[227] A later study found that measures such as banning mass gatherings and requiring the wearing of face masks could cut the death rate up to 50 percent, but this was dependent on their being imposed early in the outbreak and not being lifted prematurely.[228]

Medical treatment

[edit]As there were no antiviral drugs to treat the virus, and no antibiotics to treat the secondary bacterial infections, doctors would rely on an assortment of medicines with varying degrees of effectiveness, such as aspirin, quinine, arsenics, digitalis, strychnine, epsom salts, castor oil, and iodine.[229] Traditional treatments, such as bloodletting, ayurveda, and kampo, were also applied.[230]

Information dissemination

[edit]Due to World War I, many countries engaged in wartime censorship, and suppressed reporting of the pandemic.[231] For example, the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera was prohibited from reporting daily death tolls.[232] The newspapers of the time were also generally paternalistic and worried about mass panic.[232] Misinformation also spread along with the disease. In Ireland there was a belief that noxious gases were rising from the mass graves of Flanders Fields and being "blown all over the world by winds".[233] There were also rumors that the Germans were behind it, for example by poisoning the aspirin manufactured by Bayer, or by releasing poison gas from U-boats.[234]

Mortality

[edit]

The Spanish flu infected around 500 million people, about one-third of the world's population.[3] Estimates on deaths vary greatly, but it is considered to be one of the deadliest pandemics in history.[237][238] An early estimate from 1927 put global mortality at 21.6 million.[5] An estimate from 1991 states that the virus killed between 25 and 39 million people.[113] A 2005 estimate put the death toll at 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million.[201][239] However, a 2018 reassessment in the American Journal of Epidemiology estimated the total to be about 17 million,[5] though this has been contested.[240] Estimates done in 2021 by John M. Barry have the total death toll alone at well above 100 million.[9] With a world population of 1.8 to 1.9 billion,[241] these estimates correspond to between 1 and 6 percent of the population.

A 2009 study in Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses based on data from fourteen European countries estimated a total of 2.64 million excess deaths in Europe attributable to the Spanish flu during the 1918–1919 phase of the pandemic. This represents a mortality rate of about 1.1% of the European population (c. 250 million in 1918), considerably higher than the mortality rate in the U.S., which the authors hypothesize is likely due to the severe effects of the war in Europe.[95] The excess mortality rate in the U.K. has been estimated at 0.28%–0.4%, far below this European average.[5]

Some 12–17 million people died in India, about 5% of the population.[242] The death toll in India's British-ruled districts was 13.88 million.[243] Another estimate gives at least 12 million dead.[244] The decade between 1911 and 1921 was the only census period in which India's population fell, mostly due to devastation of the pandemic.[245][246] While India is generally described as the country most severely affected by the Spanish flu, at least one study argues that other factors may partially account for the very high excess mortality rates observed in 1918, citing unusually high 1917 mortality and wide regional variation (ranging from 0.47% to 6.66%).[5] A 2006 study in The Lancet also noted that Indian provinces had excess mortality rates ranging from 2.1% to 7.8%, stating: "Commentators at the time attributed this huge variation to differences in nutritional status and diurnal fluctuations in temperature."[247]

In Finland, 20,000 died out of 210,000 infected.[248] In Sweden, 34,000 died.[249]

In Japan, the flu killed nearly 500,000 people over two waves between 1918 and 1920, with nearly 300,000 excess deaths between October 1918 and May 1919 and 182,000 between December 1919 and May 1920.[164]

In the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), 1.5 million were assumed to have died among 30 million inhabitants.[250] In Tahiti, 13% of the population died in one month. Similarly, in Western Samoa 22% of the population of 38,000 died within two months.[251]

In Istanbul, capital of the Ottoman Empire, 6,403[252] to 10,000[119] died, giving the city a mortality rate of at least 0.56%.[252]

In New Zealand, the flu killed an estimated 6,400 Pākehā (or "New Zealanders primarily of European descent") and 2,500 Māori in six weeks, with Māori dying at eight times the rate of Pākehā.[253][254]

In Australia, the flu killed around 12,000[255] to 20,000 people.[256] The country's death rate, 2.7 per 1,000 people, was one of the lowest recorded; however, as much as 40 percent of the population were infected, and a mortality rate of 50 percent was recorded by some Aboriginal communities.[257][256] New South Wales and Victoria saw the greatest relative mortality, with 3.19 and 2.40 deaths per 1,000 people respectively, while Western Australia, Queensland, Southern Australia, and Tasmania experienced rates of 1.70, 1.14, 1.13, and 1.09 per 1,000 respectively. In Queensland, at least one-third of deaths recorded were in the Aboriginal population.[143]

In the U.S., about 20 million out of a population of 105 million became infected in the 1918–1919 season, and an estimated 500,000 to 850,000 died (0.5 to 0.8 percent of the U.S. population).[258][259][260] Native Americans tribes were particularly affected. In the Four Corners area, there were 3,293 registered deaths among Native Americans.[261] Entire Inuit and Alaskan Native village communities died in Alaska.[262] In Canada, 50,000 died.[263]

In Brazil, 300,000 died, including president Rodrigues Alves.[264]

In the UK, as many as 250,000 died; in France, more than 400,000.[265]

In Ghana, the influenza epidemic killed at least 100,000 people.[266] Tafari Makonnen (the future Emperor of Ethiopia) was one of the first Ethiopians who contracted influenza but survived.[267][268] Estimates for fatalities in the capital city, Addis Ababa, range from 5,000 to 10,000, or higher.[269]

The death toll in Russia has been estimated at 450,000, though the epidemiologists who suggested this number called it a "shot in the dark".[113] If it is correct, Russia lost roughly 0.4% of its population, meaning it suffered the lowest influenza-related mortality in Europe. Another study considers this number unlikely, given that the country was in the grip of a civil war, and the infrastructure of daily life had broken down; the study suggests that Russia's death toll was closer to 2%, or 2.7 million people.[270]

Devastated communities

[edit]

Even in areas where mortality was low, so many adults were incapacitated that daily life was hampered. Some communities closed all stores or required customers to leave orders outside. There were reports that healthcare workers could not tend the sick nor the gravediggers bury the dead because they too were ill. Mass graves were dug by steam shovel and bodies buried without coffins in many places.[271]

Bristol Bay, a region of Alaska populated by Indigenous people, suffered a death rate of 40 percent, with some villages entirely disappearing.[272] Nenana, Alaska, avoided the extent of the pandemic between 1918 and 1919, but the flu at last reached the town in spring 1920. Reports suggested that during the first two weeks of May, the majority of the town's population became infected; 10% of the population were estimated to have died, most of whom were Alaska Natives.[273]

Several Pacific island territories were hit particularly hard. The pandemic reached them from New Zealand, which was too slow to implement measures to prevent ships carrying the flu from leaving its ports. From New Zealand, the flu reached Tonga (killing 8% of the population), Nauru (16%), and Fiji (5%, 9,000 people).[274] Worst affected was Western Samoa, which had been occupied by New Zealand in 1914. 90% of the population was infected; 30% of adult men, 22% of adult women, and 10% of children died.[274] The disease spread fastest through the higher social classes among the Indigenous peoples, because of the custom of gathering oral tradition from chiefs on their deathbeds; many community elders were infected through this process.[275]

In Iran, the mortality was estimated at between 902,400 and 2,431,000, or 8% to 22% of the total population.[276] The country was going through the Persian famine of 1917–1919 concurrently.

In Ireland, during the worst 12 months, the Spanish flu accounted for one-third of all deaths.[277][278]

In South Africa it is estimated that about 300,000 people amounting to 6% of the population died within six weeks. Government actions in the early stages of the virus' arrival in the country in September 1918 are believed to have unintentionally accelerated its spread.[279] Almost a quarter of the working population of Kimberley, consisting of workers in the diamond mines, died.[280] In British Somaliland, one official estimated that 7% of the native population died.[281] This huge death toll resulted from an extremely high infection rate of up to 50% and the extreme severity of the symptoms.[113]

Other areas

[edit]In the Pacific, American Samoa[282] and the French colony of New Caledonia[283] succeeded in preventing even a single death from influenza through effective quarantines. However, the outbreak was delayed into 1926 for American Samoa and 1921 for New Caledonia as the quarantine period ended.[284] On American Samoa, at least 25% of the island residents were clinically attacked and 0.1% died, and on New Caledonia, there was widespread illness and 0.1% population died.[284] Australia also managed to avoid the first two waves with a quarantine.[223] Iceland protected a third of its population from exposure by blocking the main road of the island.[223] By the end of the pandemic, the isolated island of Marajó, in Brazil's Amazon River Delta had not reported an outbreak.[285] Saint Helena also reported no deaths.[286]

Estimates for the death toll in China have varied widely,[287][113] reflecting the lack of centralized collection of health data at the time due to the Warlord period. China may have experienced a relatively mild flu season in 1918 compared to other areas of the world.[102][104][288] However, some reports from its interior suggest that mortality rates from influenza were perhaps higher in at least a few locations in 1918.[270] At the very least, there is little evidence that China as a whole was seriously affected by the flu compared to other countries.[289]

The first estimate of the Chinese death toll was made in 1991 by Patterson and Pyle, which estimated a toll of between 5 and 9 million. However, this study was criticized by later studies due to flawed methodology, and newer studies have published estimates of a far lower mortality rate in China.[100][290] For instance, Iijima in 1998 estimates the death toll in China to be between 1 and 1.28 million based on data available from Chinese port cities.[291] The lower estimates of the Chinese death toll are based on the low mortality rates that were found in Chinese port cities and on the assumption that poor communications prevented the flu from penetrating the interior of China.[287] However, some contemporary newspaper and post office reports, as well as reports from missionary doctors, suggest that the flu did penetrate the Chinese interior and that influenza was severe in at least some locations in the countryside of China.[270]

Although medical records from China's interior are lacking, extensive medical data were recorded in Chinese port cities, such as then British-controlled Hong Kong, Canton, Peking, Harbin and Shanghai. These data were collected by the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, which was largely staffed by non-Chinese foreigners.[292] As a whole, data from China's port cities show low mortality rates compared to other cities in Asia.[292] For example, the British authorities at Hong Kong and Canton reported a mortality rate from influenza at a rate of 0.25% and 0.32%, much lower than the reported mortality rate of other cities in Asia, such as Calcutta or Bombay, where influenza was much more devastating.[292] Similarly, in the city of Shanghai – which had a population of over 2 million – there were only 266 recorded deaths from influenza among the Chinese population in 1918.[292] If extrapolated from the extensive data recorded from Chinese cities, the suggested mortality rate from influenza in China as a whole in 1918 was likely lower than 1% – much lower than the world average (which was around 3–5%).[292] In contrast, Japan and Taiwan had reported a mortality rate from influenza around 0.45% and 0.69% respectively, higher than the mortality rate collected from data in Chinese port cities, such as Hong Kong (0.25%), Canton (0.32%), and Shanghai.[292]

However, the influenza mortality rate in Hong Kong and Canton are under-recorded, because only the deaths that occurred in colony hospitals were counted.[292] Similarly, in Shanghai, these statistics are limited to that area of the city under the control of the health section of the Shanghai International Settlement; the actual death toll in Shanghai was much higher.[292] The medical records from China's interior indicate that, compared to cities, rural communities have substantially higher mortality rate.[293] A published influenza survey in Houlu County, Hebei Province, found that the case fatality rate was 9.77% and 0.79% of county population died from influenza in October and November 1918.[294]

Patterns of fatality

[edit]

The pandemic mostly killed young adults. In 1918–1919, 99% of pandemic influenza deaths in the U.S. occurred in people under 65, and nearly half of deaths were in young adults 20 to 40 years old. In 1920, the mortality rate among people under 65 had decreased sixfold to half the mortality rate of people over 65, but 92% of deaths still occurred in people under 65.[295] This is unusual since influenza is typically most deadly to weak individuals, such as infants under age two, adults over age 70, and the immunocompromised. In 1918, older adults may have had partial protection caused by exposure to the 1889–1890 flu pandemic.[296] According to historian John M. Barry, the most vulnerable of all were pregnant women. He reported that in thirteen studies of hospitalized women in the pandemic, the death rate ranged from 23% to 71%.[297] Of the pregnant women who survived childbirth, over one-quarter (26%) lost the child.[298] Another oddity was that the outbreak was widespread in the summer and autumn (in the Northern Hemisphere); influenza is usually worse in winter.[299]

There were also geographic patterns to the disease's fatality. Some parts of Asia had 30 times higher death rates than some parts of Europe, and generally, Africa and Asia had higher rates, while Europe and North America had lower ones.[300] There was also great variation within continents, with three times higher mortality in Hungary and Spain compared to Denmark, two to three times higher chance of death in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to North Africa, and possibly up to ten times higher rates between the extremes of Asia.[300] Cities were affected worse than rural areas.[300] There were also differences between cities, which might have reflected exposure to the milder first wave giving immunity, as well as the introduction of social distancing measures.[301]

Another major pattern was the differences between social classes. In Oslo, death rates were inversely correlated with apartment size, as the poorer people living in smaller apartments died at a higher rate.[302] Social status was also reflected in the higher mortality among immigrant communities, with Italian Americans, a recently arrived group at the time, nearly twice as likely to die compared to the average Americans.[300] These disparities reflected worse diets, crowded living conditions, and problems accessing healthcare.[300] Paradoxically, however, African Americans were relatively spared.[300]

More men than women were killed by the flu, as they were more likely to go out and be exposed, while women tended to stay at home.[301] For the same reason men also were more likely to have pre-existing tuberculosis, which severely worsened the chances of recovery.[301] However, in India the opposite was true, potentially because Indian women were neglected with poorer nutrition, and were expected to care for the sick.[301]

A study conducted by He et al. (2011) examined the factors that underlie variability in temporal patterns and their correlation to patterns of mortality and morbidity. Their analysis suggests that temporal variations in transmission rate provide the best explanation, and the variation in transmission required to generate these three waves is within biologically plausible values.[303] Another study by He et al. (2013) used a simple epidemic model incorporating three factors to infer the cause of the three waves of the 1918 influenza pandemic. These factors were school opening and closing, temperature changes throughout the outbreak, and human behavioral changes in response to the outbreak. Their modeling results showed that all three factors are important, but human behavioral responses showed the most significant effects.[304]

Effects

[edit]World War I

[edit]Academic Andrew Price-Smith has argued that the virus helped tip the balance of power in the latter days of the war towards the Allied cause. He provides data that the viral waves hit the Central Powers before the Allied powers and that morbidity and mortality in Germany and Austria were considerably higher than in Britain and France.[94] A 2006 Lancet study corroborates higher excess mortality rates in Germany (0.76%) and Austria (1.61%) compared to Britain (0.34%) and France (0.75%).[247]

Kenneth Kahn at Oxford University Computing Services writes that "Many researchers have suggested that the conditions of the war significantly aided the spread of the disease. And others have argued that the course of the war (and subsequent peace treaty) was influenced by the pandemic." Kahn has developed a model that can be used to test these theories.[305]

Economic

[edit]

Many businesses in the entertainment and service industries suffered losses in revenue, while the healthcare industry reported profit gains.[306] Historian Nancy Bristow has argued that the pandemic, when combined with the increasing number of women attending college, contributed to the success of women in nursing. This was due in part to the failure of medical doctors, who were predominantly men, to contain the illness. Nursing staff, who were mainly women, celebrated the success of their patient care and did not associate the spread of the disease with their work.[307]

A 2020 study found that U.S. cities that implemented early and extensive non-medical measures (quarantine, etc.) suffered no additional adverse economic effects due to implementing those measures.[308][309] However, the validity of this study has been questioned because of the coincidence of WWI and other problems with data reliability.[310]

Long-term effects

[edit]A 2006 study in the Journal of Political Economy found that "cohorts in utero during the pandemic displayed reduced educational attainment, increased rates of physical disability, lower income, lower socioeconomic status, and higher transfer payments received compared with other birth cohorts."[311] A 2018 study found that the pandemic reduced educational attainment in populations.[312] The flu has also been linked to the outbreak of encephalitis lethargica in the 1920s.[313]

Survivors faced an elevated mortality risk. Some survivors did not fully recover from physiological conditions resulting from infection.[314]

Legacy

[edit]

The Spanish flu began to fade from public awareness over the decades until the bird flu and other pandemics in the 1990s and 2000s.[315][316] This has led some historians to label the Spanish flu a "forgotten pandemic".[88] However, this label has been challenged by the historian Guy Beiner, who demonstrated how the pandemic was overshadowed by the commemoration of the First World War and mostly neglected in mainstream historiography, yet was remembered in private and local traditions across the globe.[316]

There are various theories of why the Spanish flu was "forgotten". The rapid pace of the pandemic, which killed most of its victims in the United States within less than nine months, resulted in limited media coverage. The general population was familiar with patterns of pandemic disease in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: typhoid, yellow fever, diphtheria, and cholera all occurred near the same time. These outbreaks probably lessened the significance of the influenza pandemic for the public.[317] In some areas, the flu was not reported on, the only mention being that of advertisements for medicines claiming to cure it.[318]

Additionally, the outbreak coincided with the deaths and media focus on the First World War.[319] The majority of fatalities, from both the war and the epidemic, were among young adults. The high number of war-related deaths of young adults may have overshadowed the deaths caused by flu.[295] Particularly in Europe, where the war's toll was high, the flu may not have had a tremendous psychological impact or may have seemed an extension of the war's tragedies.[295]

In literature and other media

[edit]

Despite the toll of the pandemic, it was never a large theme in American literature.[320] Alfred Crosby suspects it was overshadowed by World War I.[321] Katherine Anne Porter's 1939 novella Pale Horse, Pale Rider is one of the most well-known fictional accounts of the pandemic.[320] The 2006 novel The Last Town on Earth focuses on a town which attempts to limit the spread of the flu by preventing people from entering or leaving.[322] The Pull of the Stars is a 2020 novel by Emma Donoghue set in Dublin during the Spanish flu. Publishers fast-tracked publication because of the then ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[323]

Comparison with other pandemics

[edit]

| Name | Date | World pop. | Subtype | Reproduction number[326] | Infected (est.) | Deaths worldwide | Case fatality rate | Pandemic severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish flu[327] | 1918–20 | 1.80 billion | H1N1 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.47–2.27) | 33% (500 million)[328] or >56% (>1 billion)[329] | 17[330]–100[331][332] million | 2–3%,[329] or ~4%, or ~10%[333] | 5 |

| Asian flu | 1957–58 | 2.90 billion | H2N2 | 1.65 (IQR, 1.53–1.70) | >17% (>500 million)[329] | 1–4 million[329] | <0.2%[329] | 2 |

| Hong Kong flu | 1968–69 | 3.53 billion | H3N2 | 1.80 (IQR, 1.56–1.85) | >14% (>500 million)[329] | 1–4 million[329] | <0.2%[329][334] | 2 |

| 1977 Russian flu | 1977–79 | 4.21 billion | H1N1 | ? | ? | 0.7 million[335] | ? | ? |

| 2009 swine flu pandemic[336][337] | 2009–10 | 6.85 billion | H1N1/09 | 1.46 (IQR, 1.30–1.70) | 11–21% (0.7–1.4 billion)[338] | 151,700–575,400[339] | 0.01%[340][341] | 1 |

| Typical seasonal flu[t 1] | Every year | 7.75 billion | A/H3N2, A/H1N1, B, ... | 1.28 (IQR, 1.19–1.37) | 5–15% (340 million – 1 billion)[342] 3–11% or 5–20%[343][344] (240 million – 1.6 billion) |

290,000–650,000/year[345] | <0.1%[346] | 1 |

Notes

| ||||||||

Research

[edit]

Similarities between a reconstruction of the virus and avian viruses, combined with the human pandemic preceding the first reports of influenza in swine, led researchers to conclude the influenza virus jumped directly from birds to humans, and swine caught the disease from humans.[347][348] More recent research has suggested the strain may have originated in a nonhuman, mammalian species,[349] in 1882–1913.[350] This ancestor virus diverged about 1913–1915 into the classical swine and human H1N1 influenza lineages. The last common ancestor of human strains dates between February 1917 and April 1918. Because pigs are more readily infected with avian influenza viruses than are humans, they were suggested as the original recipients of the virus, passing the virus to humans sometime between 1913 and 1918.[350]

An effort to recreate the Spanish flu strain (a strain of influenza A subtype H1N1) was a collaboration among the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the USDA ARS Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory, and Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. The effort resulted in the announcement in 2005 that the group had successfully determined the virus' genetic sequence, using historic tissue samples recovered by pathologist Johan Hultin from an Inuit female flu victim buried in the Alaskan permafrost and samples preserved from American soldiers.[351][352][353][348] This enabled researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, led by Dr Terrence Tumpey, to synthesize RNA segments from the H1N1 virus and reconstruct infective virus particles.[354] These were subsequently used to experimentally infect mice, ferrets, and macaques, providing information about how to prevent and control future pandemics.[355]

In 2007, Kobasa et al. reported that monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) infected with the recreated flu strain exhibited classic symptoms of the 1918 pandemic, and died from an overreaction of the immune system.[356] This may explain why the Spanish flu had its surprising effect on younger, healthier people, as a person with a stronger immune system would potentially have a stronger overreaction.[357]

In December 2008, research by Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Wisconsin linked three specific genes (termed PA, PB1, and PB2) and a nucleoprotein derived from Spanish flu samples to the ability of the 1918 flu virus to invade the lungs and cause pneumonia. These genes were inserted into a modern H1N1 strain and triggered similar symptoms in animal testing.[358]

In 2008 an investigation used the virus sequence to obtain the Hemagglutinin (HA) antigen and observe the adaptive immunity in 32 survivors of the 1918 pandemic; all of them presented seroreactivity and 7 of 8 further tested presented memory B cells able to produce antibodies that bound to the HA antigen, highlighting the ability of immunological memory.[359][348]

In June 2010, a team at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine reported the 2009 flu pandemic vaccine provided some cross-protection against the Spanish flu pandemic strain.[360]

In 2013, the AIR Worldwide Research and Modeling Group "estimated the effects of a similar pandemic occurring today using the AIR Pandemic Flu Model". In the model, "a modern-day 'Spanish flu' event would result in additional life insurance losses of between US$15.3–27.8 billion in the United States alone", with 188,000–337,000 deaths in the United States.[361]

In 2018, Michael Worobey, a professor at the University of Arizona who is examining the history of the 1918 pandemic, revealed that he obtained tissue slides created by William Rolland, a physician who reported on a respiratory illness likely to be the virus while a pathologist in the British military during World War One.[362][363][364] Worobey extracted tissue from the slides to potentially reveal more about the origin of the pathogen.[26]

See also

[edit]- 1918 flu pandemic in India – Known in India as "Bombay Fever"

- 2009 swine flu pandemic – 2009–2010 pandemic of swine influenza caused by H1N1 influenza virus

- Anti-Mask League of San Francisco – 1919 San Francisco organization

- COVID-19 pandemic – Pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 (2019–2023)

- Pandemic – Widespread, often global, epidemic of severe infectious disease

- List of epidemics and pandemics

- List of Spanish flu cases

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Valentine V (20 February 2006). "Origins of the 1918 Pandemic: The Case for France". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 30 April 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ a b c Yang W, Petkova E, Shaman J (March 2014). "The 1918 influenza pandemic in New York City: age-specific timing, mortality, and transmission dynamics". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 8 (2). National Institutes of Health: 177–188. doi:10.1111/irv.12217. PMC 4082668. PMID 24299150.

- ^ a b c d e Taubenberger & Morens 2006.

- ^ "Pandemic Influenza Risk Management WHO Interim Guidance" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Spreeuwenberg P, Kroneman M, Paget J (December 2018). "Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". American Journal of Epidemiology. 187 (12). Oxford University Press: 2561–2567. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy191. PMC 7314216. PMID 30202996.

- ^ Rosenwald MS (7 April 2020). "History's deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ CDC (17 December 2019). "The Discovery and Reconstruction of the 1918 Pandemic Virus". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Spreeuwenberg (7 September 2018). "Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". Our World in Data. 187 (12): 2561–2567. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy191. PMC 7314216. PMID 30202996. Archived from the original on 7 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ a b Barry JM (2021). The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. Penguin Books. pp. 397–398. ISBN 978-0-14-303649-4.

- ^ a b Mayer J (29 January 2019). "The Origin Of The Name 'Spanish Flu'". Science Friday. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

Etymology: In ancient times, before epidemiology science, people believed the stars and "heavenly bodies" flowed into us and dictated our lives and health—influenza means 'to influence' in Italian, and the word stems from the Latin for 'flow in.' Sickness, like other unexplainable events, was attributed to the influence of the stars... But the name for the infamous 1918 outbreak, the Spanish flu, is actually a misnomer.

- ^ Gagnon, Miller & et al 2013, p. e69586.

- ^ a b More AF, Loveluck CP, Clifford H, Handley MJ, Korotkikh EV, Kurbatov AV, et al. (September 2020). "The Impact of a Six-Year Climate Anomaly on the "Spanish Flu" Pandemic and WWI". GeoHealth. 4 (9) e2020GH000277. Bibcode:2020GHeal...4..277M. doi:10.1029/2020GH000277. ISSN 2471-1403. PMC 7513628. PMID 33005839.

- ^ Marshall L (9 October 2023). "1918 flu pandemic myth debunked by skeletal remains". CU Boulder Today. Archived from the original on 26 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Brundage JF, Shanks GD (December 2007). "What really happened during the 1918 influenza pandemic? The importance of bacterial secondary infections". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196 (11): 1717–18, author reply 1718–19. doi:10.1086/522355. PMID 18008258.

- ^ Morens DM, Fauci AS (April 2007). "The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 195 (7): 1018–1028. doi:10.1086/511989. PMID 17330793.

- ^ Davis 2013, p. 7: "In short, although the Spanish flu 'had nothing "Spanish" about it,' from a strictly epidemiological perspective, its discursive link to the Iberian nation is beyond dispute. The importance of narrative for a historically informed appreciation of the epidemic stems from the importance of this discursive link and is tied directly to the scientific uncertainty about the etiological agent of the epidemic;"

- ^ "Biblical Hebrew Words and Meaning". hebrewversity. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

in the original Hebrew the people of Israel asked: "Ma'n Hu?" {?מן הוא} – English for 'what is it?' and that is the origin of the name 'manna'

- ^ Spinney 2018, p. 65: "In Freetown, a newspaper suggested that the disease be called manhu until more was known about it. Manhu, a Hebrew word meaning 'what is it?'

- ^ Cole F (1994), Sierra Leone and World War 1, University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, p. 213, 10731720, archived from the original on 11 August 2021, retrieved 11 August 2021,

local interpretations of the crisis had become deeply reminiscent of the increasing disobedience of the Israelites in the wilderness of Sin. It was therefore urged that the epidemic be called 'Man hu,' (an obvious corruption of "manna") meaning 'what is it?'

- ^ Sierra Leone Weekly News, vol. XXXV, 9 July 1918, p. 6 quoted in Mueller JW (1998), p. 8.

- ^ Hammond JA, Rolland W, Shore TH (14 July 1917). "Purulent Bronchitis". The Lancet. 190 (4898): 41–46. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(01)56229-7. ISSN 0140-6736. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2021. Alt URL Archived 26 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Radusin M (September 2012). "The Spanish flu – Part I: the first wave". Vojnosanitetski Pregled. 69 (9): 812–817. PMID 23050410.

the Purple Death ... name resulted from the specific skin colour in the most severe cases of the diseased, who by the rule also succumbed to the disease, and is also at the same time the only one which does not link this disease with the Iberian peninsula. This name is actually the most correct.

- ^ McCord CP (November 1966). "The Purple Death. Some things remembered about the influenza epidemic of 1918 at one army camp". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 8 (11). Industrial Medical Association: 593–598. PMID 5334191.

- ^ Getz D (2017). Purple death : the mysterious Spanish flu of 1918. Square Fish. ISBN 978-1-250-13909-2. OCLC 1006711971.

- ^ a b Oxford JS, Gill D (2 September 2019). "A possible European origin of the Spanish influenza and the first attempts to reduce mortality to combat superinfecting bacteria: an opinion from a virologist and a military historian". Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 15 (9): 2009–2012. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1607711. PMC 6773402. PMID 31121112.

Two papers were published in The Lancet in 1917 describing an outbreak of disease constituting 'almost a small epidemic'. The first paper was written by physicians at a hospital center in northern France,3 and the second by a team at an army hospital in Aldershot, in southern England. In both earlier instances and in the 1918 pandemic the disease was characterized by a 'dusky' cyanosis, a rapid progression from quite minor symptoms to death

- ^ a b Cox J, Gill D, Cox F, Worobey M (April 2019). "Purulent bronchitis in 1917 and pandemic influenza in 1918". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 19 (4): 360–361. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30114-8. PMID 30938298. S2CID 91189842.

- ^ Honigsbaum M (June 2018). "Spanish influenza redux: revisiting the mother of all pandemics". Lancet. 391 (10139): 2492–2495. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31360-6. PMID 29976462. S2CID 49709093.

Labelled 'purulent bronchitis' for want of a better term, the disease proved fatal in half the cases and many soldiers also developed cyanosis. 2 years later, British respiratory experts, also writing in The Lancet, but this time in the wake of the pandemic, would decide the disease had been 'fundamentally the same condition' as 'Spanish' influenza

- ^ Dennis Shanks G, Mackenzie A, Waller M, Brundage JF (July 2012). "Relationship between "purulent bronchitis" in military populations in Europe prior to 1918 and the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 6 (4): 235–239. doi:10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00309.x. PMC 5779808. PMID 22118532.

- ^ Storey, C (21 September 2020). "OLD NEWS: Influenza was an old foe long before 1918". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Opinion. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

I came across this seemingly astute analysis in the Dec. 21, 1913, Gazette.... It was a 'Special Cable to the Gazette Through the International News Service.' Grip Is a Disease Without a Country; All Nations Repudiate Malady: Each Blaming Other Kingdoms, London, Dec. 20. — The grip is a disease without a country, according to a new book just issued which is devoted to the malady. Every country tries to make it out a native of another land.... Eighteenth-century Italian writers say Dr. Hopkirk spoke of "una influenza di freddo" (influence of cold), and English physicians, mistaking the word influenza for the name of the disease itself, used it. The same term is also used in Germany, where a host of dialect names still prevail, such as lightning catarrh and fog plague.

- ^ "Grippe is not new". Los Angeles Herald. 14 January 1899. p. 6 col. 6. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

French doctors gave it the name of "la grippe," which is now anglicized into "the grip" ... It is known all over the world, and there is a disposition in every nation to shift the odium of it upon some other country. Then the Russians call it the Chinese catarrh, the Germans often call it the Russian pest, the Italians name it the German disease, and the French call it sometimes the Italian fever and sometimes the Spanish catarrh.