Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Central Intelligence Agency

View on Wikipedia

Seal of the Central Intelligence Agency | |

Flag of the Central Intelligence Agency | |

| |

George Bush Center for Intelligence in Langley, Virginia | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 18, 1947 |

| Preceding agencies | |

| Type | Independent (component of the Intelligence Community) |

| Headquarters | George Bush Center for Intelligence, Langley, Virginia, U.S. 38°57′07″N 77°08′46″W / 38.95194°N 77.14611°W |

| Motto | (Official): The Work of a Nation. The Center of Intelligence. (Unofficial): And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free[1] |

| Employees | 21,575 (estimate)[3] |

| Annual budget | $15 billion (as of 2013[update])[3][4][5] |

| Agency executives | |

| Parent department | Office of the President of the United States |

| Parent agency | Office of the Director of National Intelligence |

| Child agencies | |

| Website | cia |

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA /ˌsiː.aɪˈeɪ/) is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States tasked with advancing national security through collecting and analyzing intelligence from around the world and conducting covert operations. The agency is headquartered in the George Bush Center for Intelligence in Langley, Virginia, and is sometimes metonymously called "Langley". A major member of the United States Intelligence Community (IC), the CIA has reported to the director of national intelligence since 2004, and is focused on providing intelligence for the president and the Cabinet, though it also provides intelligence for a variety of other entities including the US Military and foreign allies.

The CIA is headed by a director and is divided into various directorates, including a Directorate of Analysis and Directorate of Operations. Unlike the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the CIA has no law enforcement function and focuses on intelligence gathering overseas, with only limited domestic intelligence collection.[6] The CIA is responsible for coordinating all human intelligence (HUMINT) activities in the IC. It has been instrumental in establishing intelligence services in many countries, and has provided support to many foreign organizations. The CIA exerts foreign political influence through its paramilitary operations units, including its Special Activities Center. It has also provided support to several foreign political groups and governments, including planning, coordinating, training and carrying out torture, and technical support. It was involved in many regime changes and carrying out planned assassinations of foreign leaders and terrorist attacks against civilians.

During World War II, U.S. intelligence and covert operations had been undertaken by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The office was abolished in 1945 by President Harry S. Truman, who created the Central Intelligence Group in 1946. Amid the intensifying Cold War, the National Security Act of 1947 established the CIA, headed by a director of central intelligence (DCI). The Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949 exempted the agency from most Congressional oversight, and during the 1950s, it became a major instrument of U.S. foreign policy. The CIA employed psychological operations against communist regimes, and backed coups to advance American interests. Major CIA-backed operations include the 1953 coup in Iran, the 1954 coup in Guatemala, the Bay of Pigs Invasion of Cuba in 1961, and the 1973 coup in Chile. In 1975, the Church Committee of the U.S. Senate revealed illegal operations such as MKUltra and CHAOS, after which greater oversight was imposed. In the 1980s, the CIA supported the Afghan mujahideen and Nicaraguan Contras, and after the September 11 attacks in 2001, played a role in the Global War on Terrorism.

The agency has been the subject of numerous controversies, including its use of political assassinations, torture, domestic wiretapping, propaganda, mind control techniques, and drug trafficking, among others.

Purpose

[edit]When the CIA was created, its purpose was to create a clearinghouse for foreign policy intelligence and analysis, collecting, analyzing, evaluating, and disseminating foreign intelligence, and carrying out covert operations.[7]

As of 2013, the CIA had five priorities:[3]

- Counterterrorism

- Nonproliferation of weapons of mass destruction

- Indications and warnings for senior policymakers

- Counterintelligence

- Cyber intelligence

Organizational structure

[edit]

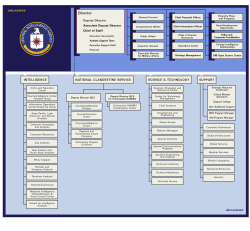

The CIA has an executive office and five major directorates:

- The Directorate of Digital Innovation

- The Directorate of Analysis

- The Directorate of Operations

- The Directorate of Support

- The Directorate of Science and Technology

Executive Office

[edit]The director of the Central Intelligence Agency (D/CIA) is appointed by the president with Senate confirmation and reports directly to the director of national intelligence (DNI); in practice, the CIA director interfaces with the DNI, Congress, and the White House, while the deputy director (DD/CIA) is the internal executive of the CIA and the chief operating officer (COO/CIA), known as executive director until 2017, leads the day-to-day work[8] as the third-highest post of the CIA.[9] The deputy director is formally appointed by the director without Senate confirmation,[9][10] but as the president's opinion plays a great role in the decision,[10] the deputy director is generally considered a political position, making the chief operating officer the most senior non-political position for CIA career officers.[11]

The Executive Office also supports the U.S. military, including the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command, by providing it with information it gathers, receiving information from military intelligence organizations, and cooperating with field activities. The associate deputy director of the CIA is in charge of the day-to-day operations of the agency. Each branch of the agency has its own director.[8] The Office of Military Affairs (OMA), subordinate to the associate deputy director, manages the relationship between the CIA and the Unified Combatant Commands, who produce and deliver regional and operational intelligence and consume national intelligence produced by the CIA.[12]

Directorate of Analysis

[edit]The Directorate of Analysis, through much of its history known as the Directorate of Intelligence (DI), is tasked with helping "the President and other policymakers make informed decisions about our country's national security" by looking "at all the available information on an issue and organiz[ing] it for policymakers".[13] The directorate has four regional analytic groups, six groups for transnational issues, and three that focus on policy, collection, and staff support.[14] There are regional analytical offices covering the Near East and South Asia, Russia, and Europe; and the Asia–Pacific, Latin America, and Africa.

Directorate of Operations

[edit]The Directorate of Operations is responsible for collecting foreign intelligence (mainly from clandestine HUMINT sources), and for covert action. The name reflects its role as the coordinator of human intelligence activities between other elements of the wider U.S. intelligence community with their HUMINT operations. This directorate was created in an attempt to end years of rivalry over influence, philosophy, and budget between the United States Department of Defense (DOD) and the CIA. In spite of this, the Department of Defense announced in 2012 its intention to organize its own global clandestine intelligence service, the Defense Clandestine Service (DCS),[15] under the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). Contrary to some public and media misunderstanding, DCS is not a "new" intelligence agency but rather a consolidation, expansion and realignment of existing Defense HUMINT activities, which have been carried out by DIA for decades under various names, most recently as the Defense Human Intelligence Service.[16]

This Directorate is known to be organized by geographic regions and issues, but its precise organization is classified.[17]

Directorate of Science & Technology

[edit]The Directorate of Science & Technology was established to research, create, and manage technical collection disciplines and equipment. Many of its innovations were transferred to other intelligence organizations, or, as they became more overt, to the military services.

The development of the U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft, for instance, was done in cooperation with the United States Air Force. The U-2's original mission was clandestine imagery intelligence over denied areas such as the Soviet Union.[18]

Directorate of Support

[edit]The Directorate of Support has organizational and administrative functions to significant units including:

- The Office of Security

- The Office of Communications

- The Office of Information Technology

Directorate of Digital Innovation

[edit]The Directorate of Digital Innovation (DDI) focuses on accelerating innovation across the Agency's mission activities. It is the Agency's newest directorate. The Langley, Virginia-based office's mission is to streamline and integrate digital and cybersecurity capabilities into the CIA's espionage, counterintelligence, all-source analysis, open-source intelligence collection, and covert action operations.[19] It provides operations personnel with tools and techniques to use in cyber operations. It works with information technology infrastructure and practices cyber tradecraft.[20] This means retrofitting the CIA for cyberwarfare. DDI officers help accelerate the integration of innovative methods and tools to enhance the CIA's cyber and digital capabilities on a global scale and ultimately help safeguard the United States. They also apply technical expertise to exploit clandestine and publicly available information (also known as open-source data) using specialized methodologies and digital tools to plan, initiate and support the technical and human-based operations of the CIA.[21] Before the establishment of the new digital directorate, offensive cyber operations were undertaken by the CIA's Information Operations Center.[22] Little is known about how the office specifically functions or if it deploys offensive cyber capabilities.[19]

The directorate had been covertly operating since approximately March 2015 but formally began operations on October 1, 2015.[23] According to classified budget documents, the CIA's computer network operations budget for fiscal year 2013 was $685.4 million. The NSA's budget was roughly $1 billion at the time.[24]

Rep. Adam Schiff, the California Democrat who served as the ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee, endorsed the reorganization. "The director has challenged his workforce, the rest of the intelligence community, and the nation to consider how we conduct the business of intelligence in a world that is profoundly different from 1947 when the CIA was founded," Schiff said.[25]

Office of Congressional Affairs

[edit]The Office of Congressional Affairs (OCA) serves as the liaison between the CIA and the US Congress. The OCA states that it aims to ensure that Congress is fully and currently informed of intelligence activities.[26]

The office is the CIA's primary interface with Congressional oversight committees, leadership, and members. It is responsible for all matters pertaining to congressional interaction and oversight of US intelligence activities. It claims that it aims to:[27]

- ensure that Congress is kept informed of intelligence issues and activities by providing timely briefings and notifications

- facilitate prompt and complete responses to congressional requests for information and inquiries

- maintain a record of the Agency's interaction with Congress

- track legislation that could affect the Agency

- educate Agency personnel about their responsibility to keep Congress fully and currently informed

Training

[edit]The CIA established its first training facility, the Office of Training and Education, in 1950. Following the end of the Cold War, the CIA's training budget was slashed, which had a negative effect on employee retention.[28][29]

In response, Director of Central Intelligence George Tenet established CIA University in 2002.[28][13] CIA University holds between 200 and 300 courses each year, training both new hires and experienced intelligence officers, as well as CIA support staff.[28][29] The facility works in partnership with the National Intelligence University, and includes the Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis, the Directorate of Analysis' component of the university.[13][30][31]

For later stage training of student operations officers, there is at least one classified training area at Camp Peary, near Williamsburg, Virginia. Students are selected, and their progress evaluated, in ways derived from the OSS, published as the book Assessment of Men, Selection of Personnel for the Office of Strategic Services.[32] Additional mission training is conducted at Harvey Point, North Carolina.[33]

The primary training facility for the Office of Communications is Warrenton Training Center, located near Warrenton, Virginia. The facility was established in 1951 and has been used by the CIA since at least 1955.[34][35]

Budget

[edit]Details of the overall United States intelligence budget are classified.[3] Under the Central Intelligence Agency Act of 1949, the Director of Central Intelligence is the only federal government employee who can spend "un-vouchered" government money.[36] The government showed its 1997 budget was $26.6 billion for the fiscal year.[37] The government has disclosed a total figure for all non-military intelligence spending since 2007; the fiscal 2013 figure is $52.6 billion. According to the 2013 mass surveillance disclosures, the CIA's fiscal 2013 budget is $14.7 billion, 28% of the total and almost 50% more than the budget of the National Security Agency. CIA's HUMINT budget is $2.3 billion, the SIGINT budget is $1.7 billion, and spending for security and logistics of CIA missions is $2.5 billion. "Covert action programs," including a variety of activities such as the CIA's drone fleet and anti-Iranian nuclear program activities, accounts for $2.6 billion.[3]

There were numerous previous attempts to obtain general information about the budget.[38] As a result, reports revealed that CIA's annual budget in Fiscal Year 1963 was $550 million (equivalent to US$5.6 billion in 2024),[39] and the overall intelligence budget in FY 1997 was US$26.6 billion (equivalent to US$52.1 billion in 2024).[40] There have been accidental disclosures; for instance, Mary Margaret Graham, a former CIA official and deputy director of national intelligence for collection in 2005, said that the annual intelligence budget was $44 billion,[41] and in 1994 Congress accidentally published a budget of $43.4 billion (in 2012 dollars) in 1994 for the non-military National Intelligence Program, including $4.8 billion for the CIA.[3]

After the Marshall Plan was approved, appropriating $13.7 billion over five years, 5% of those funds or $685 million were secretly made available to the CIA. A portion of the enormous M-fund, established by the U.S. government during the post-war period for reconstruction of Japan, was secretly steered to the CIA.[42]

Relationship with other intelligence agencies

[edit]Foreign intelligence services

[edit]The role and functions of the CIA are roughly equivalent to those of the Federal Intelligence Service (BND) in Germany, MI6 in the United Kingdom, the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) in Australia, the Directorate-General for External Security (DGSE) in France, the Foreign Intelligence Service in Russia, the Ministry of State Security (MSS) in China, the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) in India, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) in Pakistan, the General Intelligence Service in Egypt, Mossad in Israel, and the National Intelligence Service (NIS) in South Korea.

The CIA was instrumental in the establishment of intelligence services in several U.S. allied countries, including Germany's BND and Greece's EYP (then known as KYP).[43][citation needed]

The closest links of the U.S. intelligence community to other foreign intelligence agencies are to Anglophone countries: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Special communications signals that intelligence-related messages can be shared with these four countries.[44] An indication of the United States' close operational cooperation is the creation of a new message distribution label within the main U.S. military communications network. Previously, the marking of NOFORN (i.e., No Foreign Nationals) required the originator to specify which, if any, non-U.S. countries could receive the information. A new handling caveat, USA/AUS/CAN/GBR/NZL Five Eyes, used primarily on intelligence messages, indicates that the material can be shared with Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and New Zealand.

The task of the division called "Verbindungsstelle 61" of the German Bundesnachrichtendienst is keeping contact to the CIA office in Wiesbaden.[45]

History

[edit]Immediate predecessors

[edit]

During World War II, U.S. intelligence and covert operations were undertaken by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).[46] Many future CIA officers, including four directors of Central Intelligence, served in the OSS.[47] On September 20, 1945, shortly after the end of World War II, Truman signed an executive order dissolving the OSS.[48] By October 1945 its functions had been divided between the Departments of State and War. The division lasted only a few months.

The first public mention of the "Central Intelligence Agency" appeared on a command-restructuring proposal presented by Jim Forrestal and Arthur Radford to the U.S. Senate Military Affairs Committee at the end of 1945.[49] Army Intelligence agent Colonel Sidney Mashbir and Commander Ellis Zacharias worked together for four months at the direction of Fleet Admiral Joseph Ernest King, and prepared the first draft and implementing directives for the creation of what would become the Central Intelligence Agency.[50][51][52] Despite opposition from the military establishment, the State Department, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI),[53] Truman established the National Intelligence Authority[54] in January 1946. Its operational extension was known as the Central Intelligence Group (CIG),[55] which was the direct predecessor of the CIA.[56]

Creation

[edit]The Central Intelligence Agency was created on July 26, 1947, when President Truman signed the National Security Act into law. A major impetus for the creation of the agency was growing tensions with the USSR following the end of World War II.[57]

Lawrence Houston, head counsel of the SSU, CIG, and, later CIA, was principal draftsman of the National Security Act of 1947,[58][59][60] which dissolved the NIA and the CIG, and established both the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency.[55][61] In 1949, Houston helped to draft the Central Intelligence Agency Act (Pub. L. 81–110), which authorized the agency to use confidential fiscal and administrative procedures, and exempted it from most limitations on the use of federal funds. The act also exempted the CIA from having to disclose its "organization, functions, officials, titles, salaries, or numbers of personnel employed," and created the program "PL-110" to handle defectors and other "essential aliens" who fell outside normal immigration procedures.[62][63]

At the outset of the Korean War, the CIA still only had a few thousand employees, around one thousand of whom worked in analysis. Intelligence primarily came from the Office of Reports and Estimates, which drew its reports from a daily take of State Department telegrams, military dispatches, and other public documents. The CIA still lacked its intelligence-gathering abilities.[64] On August 21, 1950, shortly after, Truman announced Walter Bedell Smith as the new Director of the CIA. The change in leadership took place shortly after the start of the Korean War in South Korea, as the lack of a clear warning to the President and NSC about the imminent North Korean invasion was seen as a grave failure of intelligence.[64]

The CIA had different demands placed on it by the various bodies overseeing it. Truman wanted a centralized group to organize the information that reached him.[65][66] The Department of Defense wanted military intelligence and covert action, and the State Department wanted to create global political change favorable to the US. Thus the two areas of responsibility for the CIA were covert action and covert intelligence. One of the main targets for intelligence gathering was the Soviet Union, which had also been a priority of the CIA's predecessors.[65][66][67]

U.S. Air Force General Hoyt Vandenberg, the CIG's second director, created the Office of Special Operations (OSO) and the Office of Reports and Estimates (ORE).[66] Initially, the OSO was tasked with spying and subversion overseas with a budget of $15 million (equivalent to $196 million in 2024),[68] the largesse of a small number of patrons in Congress. Vandenberg's goals were much like the ones set out by his predecessor: finding out "everything about the Soviet forces in Eastern and Central Europe – their movements, their capabilities, and their intentions."[69]

On June 18, 1948, the National Security Council issued Directive 10/2[70] calling for covert action against the Soviet Union,[71] and granting the authority to carry out covert operations against "hostile foreign states or groups" that could, if needed, be denied by the U.S. government. To this end, the Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) was created inside the CIA.[72] The OPC was unique; Frank Wisner, the head of the OPC, answered not to the CIA Director, but to the secretaries of defense, state, and the NSC. The OPC's actions were a secret even from the head of the CIA. Most CIA stations had two station chiefs, one working for the OSO, and one working for the OPC.[73]

The agency was unable to provide sufficient intelligence about the Soviet takeovers of Romania and Czechoslovakia, the Soviet blockade of Berlin, or the Soviet atomic bomb project. In particular, the agency failed to predict the Chinese entry into the Korean War with 300,000 troops.[74][75] The famous double agent Kim Philby was the British liaison to American Central Intelligence.[76] Through him, the CIA coordinated hundreds of airdrops inside the iron curtain, all compromised by Philby. Arlington Hall, the nerve center of CIA cryptanalysis, was compromised by Bill Weisband, a Russian translator and Soviet spy.[77]

However, the CIA was successful in influencing the 1948 Italian election in favor of the Christian Democrats.[78] The $200 million Exchange Stabilization Fund (equivalent to $2.6 billion in 2024),[68] earmarked for the reconstruction of Europe, was used to pay wealthy Americans of Italian heritage. Cash was then distributed to Catholic Action, the Vatican's political arm, and directly to Italian politicians. This tactic of using its large fund to purchase elections was frequently repeated in the subsequent years.[79]

Korean War

[edit]At the beginning of the Korean War, CIA officer Hans Tofte claimed to have turned a thousand North Korean expatriates into a guerrilla force tasked with infiltration, guerrilla warfare, and pilot rescue.[80] In 1952 the CIA sent 1,500 more expatriate agents north. Seoul station chief Albert Haney would openly celebrate the capabilities of those agents and the information they sent.[80] In September 1952 Haney was replaced by John Limond Hart, a Europe veteran with a vivid memory for bitter experiences of misinformation.[80] Hart was suspicious of the parade of successes reported by Tofte and Haney and launched an investigation which determined that the entirety of the information supplied by the Korean sources was false or misleading.[81] After the war, internal reviews by the CIA corroborated Hart's findings. The CIA's station in Seoul had 200 officers, but not a single speaker of Korean.[81] Hart reported to Washington that Seoul station could not be salvaged. Loftus Becker, deputy director of intelligence, was sent personally to tell Hart that the CIA had to keep the station open to save face. Becker returned to Washington, D.C., pronouncing the situation to be "hopeless".[81] He then resigned. Air Force Colonel James Kallis stated that CIA director Allen Dulles continued to praise the CIA's Korean force, despite knowing that they were under enemy control.[82] When China entered the war in 1950, the CIA attempted a number of subversive operations in the country, all of which failed due to the presence of double agents. Millions of dollars were spent in these efforts.[83] These included a team of young CIA officers airdropped into China who were ambushed, and CIA funds being used to set up a global heroin empire in Burma's Golden Triangle following a betrayal by another double agent.[83]

1953 Iranian coup d'état

[edit]

In 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh, a member of the National Front, was elected Iranian prime-minister.[84] As prime minister, he nationalized the Anglo-Persian Oil Company which his predecessor had supported. The nationalization of the British-funded Iranian oil industry, including the largest oil refinery in the world, was disastrous for Mosaddegh. A British naval embargo closed the British oil facilities, which Iran had no skilled workers to operate. In 1952, Mosaddegh resisted the royal refusal to approve his Minister of War and resigned in protest. The National Front took to the streets in protest. Fearing a loss of control, the military pulled its troops back five days later, and Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi gave in to Mosaddegh's demands. Mosaddegh quickly replaced military leaders loyal to the Shah with those loyal to him, giving him personal control over the military. Given six months of emergency powers, Mosaddegh unilaterally passed legislation. When that six months expired, his powers were extended for another year. In 1953, Mossadegh dismissed parliament and assumed dictatorial powers. This power grab triggered the Shah to exercise his constitutional right to dismiss Mosaddegh. Mosaddegh launched a military coup, and the Shah fled the country.

Under CIA Director Allen Dulles, Operation Ajax was put into motion. Its goal was to overthrow Mossadegh with military support from General Fazlollah Zahedi and install a pro-western regime headed by the Shah of Iran. Kermit Roosevelt Jr. oversaw the operation in Iran.[85] On August 16, a CIA paid mob led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini would spark what a U.S. embassy officer called "an almost spontaneous revolution"[86] but Mosaddegh was protected by his new inner military circle, and the CIA had been unable to gain influence within the Iranian military. Their chosen man, former General Fazlollah Zahedi, had no troops to call on.[87] After the failure of the first coup, Roosevelt paid demonstrators to pose as communists and deface public symbols associated with the Shah. This August 19 incident helped foster public support of the Shah and led gangs of citizens on a spree of violence intent on destroying Mossadegh.[88] An attack on his house forced Mossadegh to flee. He surrendered the next day, and his coup came to an end.[89]

1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

[edit]

The return of the Shah to power, and the impression that an effective CIA had been able to guide that nation to friendly and stable relations with the West, triggered planning for Operation PBSuccess, a plan to overthrow Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz.[90] The plan was exposed in major newspapers before it happened after a CIA agent left plans for the coup in his Guatemala City hotel room.[91]

The Guatemalan Revolution of 1944–54 overthrew the U.S. backed dictator Jorge Ubico and brought a democratically elected government to power. The government began an ambitious agrarian reform program which sought to grant land to millions of landless peasants. The program threatened the land holdings of the United Fruit Company, who lobbied for a coup by portraying these reforms as communist.[92][93][94][95]

On June 18, 1954, Carlos Castillo Armas led 480 CIA-trained men across the border from Honduras into Guatemala. The weapons had also come from the CIA.[96] The CIA mounted a psychological campaign to convince the Guatemalan people and government that Armas's victory was a fait accompli. Its largest aspect was a radio broadcast entitled "The Voice of Liberation" which announced that Guatemalan exiles led by Castillo Armas were shortly about to liberate the country.[96] On June 25, a CIA plane bombed Guatemala City, destroying the government's main oil reserves. Árbenz ordered the army to distribute weapons to local peasants and workers.[97] The army refused, forcing Jacobo Árbenz's resignation on June 27, 1954. Árbenz handed over power to Colonel Carlos Enrique Diaz.[97] The CIA then orchestrated a series of power transfers that ended with the confirmation of Castillo Armas as president in July 1954.[97] Armas was the first in a series of military dictators that would rule the country, leading to the brutal Guatemalan Civil War from 1960 to 1996, in which some 200,000 people were killed, mostly by the U.S.-backed military.[102]

Syria

[edit]

In 1949, Colonel Adib Shishakli rose to power in Syria in a CIA-backed coup. Four years later, he would be overthrown by the military, Ba'athists, and communists. The CIA and MI6 started funding right-wing members of the military but suffered a huge setback in the aftermath of the Suez Crisis. CIA Agent Rocky Stone, who had played a minor role in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, was working at the Damascus embassy as a diplomat but was the station chief. Syrian officers on the CIA dole quickly appeared on television stating that they had received money from "corrupt and sinister Americans" "in an attempt to overthrow the legitimate government of Syria."[103] Syrian forces surrounded the embassy and rousted Agent Stone, who confessed and subsequently made history as the first American diplomat expelled from an Arab nation. This strengthened ties between Syria and Egypt, helping establish the United Arab Republic, and poisoning the well for the US for the foreseeable future.[103]

Indonesia

[edit]The United States was suspicious of Sukarno, Indonesia's president, because of his declaration of neutrality in the Cold War.[104] After Sukarno hosted the Bandung Conference, promoting the Non-Aligned Movement, the Eisenhower White House responded with NSC 5518 authorizing "all feasible covert means" to move Indonesia into the Western sphere.[105]

The U.S. had no clear policy on Indonesia. Eisenhower sent his special assistant for security operations, F. M. Dearborn Jr., to Jakarta. His report that there was high instability, and that the US lacked stable allies, reinforced the domino theory. Indonesia suffered from what he described as "subversion by democracy".[106] The CIA decided to attempt another military coup in Indonesia, where the Indonesian military was trained by the US, had a strong professional relationship with the US military, had a pro-American officer corps that strongly supported their government, and a strong belief in civilian control of the military, instilled partly by its close association with the US military.[107]

On September 25, 1957, Eisenhower ordered the CIA to start a revolution in Indonesia with the goal of regime change. Three days later, Blitz, a Soviet-controlled weekly in India,[108] reported that the US was plotting to overthrow Sukarno. The story was picked up by the media in Indonesia. One of the first parts of the operation was an 11,500-ton US Navy ship landing at Sumatra, delivering weapons for as many as 8,000 potential revolutionaries.[109]

In support of the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia-Permesta Movement, formed by dissident military commanders in Central Sumatera and North Sulawesi with the aim of overthrowing the Sukarno regime, a B-26 piloted by CIA agent Allen Lawrence Pope attacked Indonesian military targets in April and May 1958.[110] The CIA described the airstrikes to the President as attacks by "dissident planes." Pope's B-26 was shot down over Ambon, Indonesia on May 18, 1958, and he bailed out. When he was captured, the Indonesian military found his personnel records, after-action reports, and his membership card for the officer's club at Clark Field. On March 9, John Foster Dulles, the Secretary of State and brother of DCI Allen Dulles, made a public statement calling for a revolt against communist despotism under Sukarno. Three days later, the CIA reported to the White House that the Indonesian Army's actions against the CIA-supported revolution were suppressing communism.[111]

After Indonesia, Eisenhower displayed mistrust of both the CIA and its director, Allen Dulles. Dulles too displayed mistrust of the CIA itself. Abbot Smith, a CIA analyst who later became chief of the Office of National Estimates, said, "We had constructed for ourselves a picture of the USSR, and whatever happened had to be made to fit into this picture. Intelligence estimators can hardly commit a more abominable sin." On December 16, Eisenhower received a report from his intelligence board of consultants that said the agency was "incapable of making objective appraisals of its own intelligence information as well as its own operations."[112]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]The Congo became independent from Belgium in 1960.[113] The United States feared that its new prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, was susceptible to Soviet influence, so the CIA supported Joseph Mobutu in organizing a coup that deposed Lumumba on September 14, 1960.[114] Lumumba was assassinated by his Congolese and Belgian enemies in 1961, with CIA acquiescence.[115] The CIA continued to back the Mobutu regime throughout the Cold War, despite its corruption, mismanagement, and human rights abuses.[116]

1960 U-2 incident

[edit]

After the bomber gap came the missile gap. Eisenhower wanted to use the U-2 to disprove the Missile Gap, but he had banned U-2 overflights of the USSR after meeting Secretary Khrushchev at Camp David. Another reason the President objected to the use of the U-2 was that, in the nuclear age, the intelligence he needed most was on their intentions, without which, the US would face a paralysis of intelligence. He was particularly worried that U-2 flights could be seen as preparations for first-strike attacks. He had high hopes for an upcoming meeting with Khrushchev in Paris. Eisenhower finally gave in to CIA pressure to authorize a 16-day window for flights, which was extended an additional six days because of poor weather. On May 1, 1960, the Soviet Air Forces shot down a U-2 flying over Soviet territory. To Eisenhower, the ensuing coverup destroyed his perceived honesty and his hope of leaving a legacy of thawing relations with Khrushchev. Eisenhower later said that the U-2 coverup was the greatest regret of his presidency.[117]: 160

Bay of Pigs

[edit]

The CIA welcomed Fidel Castro on his visit to Washington, D.C., and gave him a face-to-face briefing. The CIA hoped that Castro would bring about a friendly democratic government and planned to support his government with money and guns. By December 11, 1959, however, a memo reached the DCI's desk recommending Castro's "elimination." Dulles replaced the word "elimination" with "removal," and set the scheme into action. By mid-August 1960, Dick Bissell sought, with the full backing of the CIA, to hire the Mafia to assassinate Castro.[119]

The Bay of Pigs Invasion was a failed military invasion of Cuba undertaken by the CIA-sponsored paramilitary group Brigade 2506 on April 17, 1961. A counter-revolutionary military, trained and funded by the CIA, Brigade 2506 fronted the armed wing of the Democratic Revolutionary Front (DRF) and intended to overthrow Castro's increasingly communist government. Launched from Guatemala, the invading force was defeated within three days by the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, under Castro's direct command. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower was concerned at the direction Castro's government was taking, and in March 1960, Eisenhower allocated $13.1 million to the CIA to plan his overthrow. The CIA proceeded to organize the operation with the aid of various Cuban counter-revolutionary forces, training Brigade 2506 in Guatemala. Over 1,400 paramilitaries set out for Cuba by boat on April 13 for a marine invasion. Two days later on April 15, eight CIA-supplied B-26 bombers attacked Cuban airfields. On the night of April 16, the land invasion began in the Bay of Pigs, but by April 20, the invaders finally surrendered. The failed invasion strengthened the position of Castro's leadership as well as his ties with the USSR. This led eventually to the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. The invasion was a major embarrassment for US foreign policy.

The Taylor Board was commissioned to determine what went wrong in Cuba. The Board came to the same conclusion that the Jan '61 President's Board of Consultants on Foreign Intelligence Activities had concluded, and many other reviews prior, and to come, that Covert Action had to be completely isolated from intelligence and analysis. The Inspector General of the CIA investigated the Bay of Pigs. He concluded that there was a need to improve the organization and management of the CIA drastically.

Cuba: Terrorism and sabotage

[edit]After the failure of the attempted invasion at the Bay of Pigs, the CIA proposed Operation Mongoose, a program of sabotage and terrorist attacks against civilian and military targets in Cuba, with the stated intent to bring down the Cuban administration and institute a new government.[120] It also sought to force the Cuban government to introduce intrusive civil measures and divert resources to protect its citizens from the attacks.[121] It was authorized by President Kennedy in November 1961.[122][123][124][125] The operation saw the CIA engage in an extensive campaign of terrorist attacks against civilians and economic targets, killing significant numbers of civilians, and carry out covert operations against the Cuban government.[123][126][127][128]

The CIA established a base for the operation, with the cryptonym JMWAVE, at a disused naval facility on the University of Miami campus. The operation was so extensive that it housed the largest number of CIA officers outside of Langley, eventually numbering some four hundred. It was a major employer in Florida, with several thousand agents in clandestine pay of the agency.[129][130] The terrorist activities carried out by agents armed, organized and funded by the CIA were a further source of tension between the U.S. and Cuban governments. They were a major factor contributing to the Soviet decision to place missiles in Cuba, leading to the Cuban Missile Crisis.[131][132]

The attacks continued through 1965.[132] Though the level of terrorist activity directed by the CIA lessened in the second half of the 1960s, in 1969 the CIA was directed to intensify its operations against Cuba.[133] Exile terrorists were still in the employ of the CIA in the mid-1970s, including Luis Posada Carriles.[134][135][136] He remained on the CIA's payroll until mid-1976,[134][136] and is widely believed to be responsible for the October 1976 Cubana 455 flight bombing, killing 73 people – the deadliest instance of airline terrorism in the western hemisphere prior to the attacks of September 2001 in New York.[134][135][136]

Despite the damage done and civilians killed in the CIA's terrorist attacks, by the measure of its stated objective the project was a complete failure.[126][127]

Brazil

[edit]The CIA and the United States government were involved in the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état. The coup occurred from March 31 to April 1, which resulted in the Brazilian Armed Forces ousting President João Goulart. The United States saw Goulart as a left-wing threat in Latin America. Secret cables written by the US Ambassador to Brazil, Lincoln Gordon, confirmed that the CIA was involved in covert action in Brazil. The CIA encouraged "pro-democracy street rallies" in Brazil, for instance, to create dissent against Goulart.[137]

Tibet

[edit]The CIA Tibetan program consisted of political plots, propaganda distribution, paramilitary operations, and intelligence gathering based on U.S. commitments made to the Dalai Lama in 1951 and 1956.[138]

Indochina and the Vietnam War (1954–1975)

[edit]The OSS Patti mission arrived in Vietnam near the end of World War II and had significant interaction with the leaders of many Vietnamese factions, including Ho Chi Minh.[139]

During the period of U.S. combat involvement in the Vietnam War, there was considerable argument about progress among the Department of Defense under Robert McNamara, the CIA, and, to some extent, the intelligence staff of Military Assistance Command Vietnam.[140]

Sometime between 1959 and 1961, the CIA started Project Tiger, a program of dropping South Vietnam agents into North Vietnam to gather intelligence. These were failures; the Deputy Chief for Project Tiger, Captain Do Van Tien, admitted that he was an agent for Hanoi.[141]

In the face of the failure of Project Tiger, the Pentagon wanted CIA paramilitary forces to participate in their Op Plan 64A. This resulted in the CIA's foreign paramilitaries being put under the command of the DOD, a move seen as a slippery slope inside the CIA, a slide from covert action towards militarization.[142]

The antiwar movement rapidly expanded across the United States during the Johnson presidency. Johnson wanted CIA Director Richard Helms to substantiate Johnson's hunch that Moscow and Beijing were financing and influencing the American antiwar movement.[143] Thus, in the fall of 1967, the CIA launched a domestic surveillance program code-named Chaos that would linger for a total of seven years. Police departments across the country cooperated in tandem with the agency, amassing a "computer index of 300,000 names of American people and organizations, and extensive files on 7,200 citizens." Helms hatched a "Special Operations Group" in which "[eleven] CIA officers grew long hair, learned the jargon of the New Left, and went off to infiltrate peace groups in the United States and Europe."[144] A CIA analyst's assessment of Vietnam was that the U.S. was "becoming progressively divorced from reality... [and] proceeding with far more courage than wisdom".[145]

From 1968 to 1972, the CIA's Phoenix Program involved the killing, without trial, of between twenty and forty thousand South Vietnamese civilians suspected to be members of what Americans called the "Infrastructure" – the non-military administrative and political components of the Communists' organizational structure. Thousands were tortured prior to being killed, by such methods as the repeated application of electrical shock to the brain, and the drilling of a dowel through the ear canal into the brain until the person died.[146]

Abuses of CIA authority, 1970s

[edit]

Conditions worsened in the mid-1970s, around the time of Watergate. A dominant feature of political life during that period were the attempts of Congress to assert oversight of the U.S. presidency and the executive branch of the U.S. government. Revelations about past CIA activities, such as assassinations and attempted assassinations of foreign leaders (most notably Fidel Castro and Rafael Trujillo) and illegal domestic spying on U.S. citizens, provided the opportunities to increase Congressional oversight of U.S. intelligence operations.[147]

In 1971, the NSA and CIA were engaged in domestic spying; the DOD was eavesdropping on Henry Kissinger. The White House and Camp David were wired for sound. Nixon and Kissinger were eavesdropping on their aides, as well as reporters. Famously, Nixon's Plumbers had in their number many former CIA officers, including Howard Hunt, Jim McCord, and Eugenio Martinez. On July 7, 1971, John Ehrlichman, Nixon's domestic policy chief, told DCI Cushman, Nixon's hatchet-man in the CIA, to let Cushman "know that [Hunt] was, in fact, doing some things for the President... you should consider he has pretty much carte blanche".[148]

Hastening the CIA's fall from grace was the burglary of the Watergate headquarters of the Democratic Party by former CIA officers, and President Richard Nixon's subsequent attempt to use the CIA to impede the FBI's investigation of the burglary. In the famous "smoking gun" recording that led to President Nixon's resignation, Nixon ordered his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, to tell the CIA that further investigation of Watergate would "open the whole can of worms about the Bay of Pigs".[149][150] In this way Nixon and Haldeman ensured that the CIA's No. 1 and No. 2 ranking officials, Richard Helms and Vernon Walters, communicated to FBI Director L. Patrick Gray that the FBI should not follow the money trail from the burglars to the Committee to Re-elect the President, as it would uncover CIA informants in Mexico. The FBI initially agreed to this due to a long-standing agreement between the FBI and CIA not to uncover each other's sources of information, though within a couple of weeks the FBI resumed its investigation. Nonetheless, when the smoking gun tapes were made public, damage to the public's perception of CIA's top officials, and thus to the CIA as a whole, could not be avoided.[151]

On November 13, 1972, after Nixon's landslide re-election, Nixon told Kissinger "[I intend] to ruin the Foreign Service. I mean ruin it – the old Foreign Service – and to build a new one." He had similar designs for the CIA and intended to replace Helms with James Schlesinger.[152] Nixon had promised that Helms could stay on until his 60th birthday, the mandatory retirement age. On February 2, Nixon broke that promise, carrying through with his intention to "remove the deadwood" from the CIA. "Get rid of the clowns" was his order to the incoming CI. Kissinger had been running the CIA since the beginning of Nixon's presidency, but Nixon impressed on Schlesinger that he must appear to Congress to be in charge, averting their suspicion of Kissinger's involvement.[153] Nixon also hoped that Schlesinger could push through broader changes in the intelligence community that he had been working towards for years, the creation of a Director of National Intelligence, and spinning off the covert action part of the CIA into a separate organ. Before Helms would leave office, he would destroy every tape he had secretly made of meetings in his office, and many of the papers on Project MKUltra. In Schlesinger's 17-week tenure, in his assertion to President Nixon that it was "imperative to cut back on 'the prominence of CIA operations' around the world," the director fired more than 1,500 employees.[154] As Watergate threw the spotlight on the CIA, Schlesinger, who had been kept in the dark about the CIA's involvement, decided he needed to know what skeletons were in the closet

This became the Family Jewels. It included information linking the CIA to the assassination of foreign leaders, the illegal surveillance of some 7,000 U.S. citizens involved in the antiwar movement (Operation CHAOS), its experiments on U.S. and Canadian citizens without their knowledge, secretly giving them LSD (among other things) and observing the results.[147] This prompted Congress to create the Church Committee in the Senate, and the Pike Committee in the House. President Gerald Ford created the Rockefeller Commission,[147] and issued an executive order prohibiting the assassination of foreign leaders. DCI Colby leaked the papers to the press, later he stated that he believed that providing Congress with this information was the correct thing to do, and ultimately in the CIA's interests.[155]

In December 1974 the New York Times reported that the CIA had collected intelligence files on at least 10,000 Americans and engaged in dozens of other illegal activities beginning in the 1950s, including break-ins, wiretapping and mail inspections, in violation of its 1947 charter which prohibited it from taking action on American soil and against US citizens.[156]

Congressional investigations

[edit]Acting Attorney General Laurence Silberman learned of the existence of the Family Jewels and issued a subpoena for them, prompting eight congressional investigations on the domestic spying activities of the CIA. Bill Colby's short tenure as DCI would end with the Halloween Massacre. His replacement was George H. W. Bush. At the time, the DOD had control of 80% of the intelligence budget.[157] Communication and coordination between the CIA and the DOD would suffer greatly under Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. The CIA's budget for hiring clandestine officers had been squeezed out by the paramilitary operations in Southeast Asia, and the government's poor popularity further strained hiring. This left the agency bloated with middle management, and anemic in younger officers. With employee training taking five years, the agency's only hope would be on the trickle of new officers coming to fruition years in the future. The CIA would see another setback as communists would take Angola. William J. Casey, a member of Ford's Intelligence Advisory Board, obtained Bush's approval to allow a team from outside the CIA to produce Soviet military estimates as a "Team B". The "B" team was composed of hawks. Their estimates were the highest that could be justified, and they painted a picture of a growing Soviet military when the Soviet military was indeed shrinking. Many of their reports found their way to the press.

Chad

[edit]Chad's neighbor Libya was a major source of weaponry to communist rebel forces. The CIA seized the opportunity to arm and finance Chad's Prime Minister, Hissène Habré, after he created a breakaway government in western Sudan.[158]

Afghanistan

[edit]

In Afghanistan, the CIA funneled several billion dollars' worth of weapons,[159] including FIM-92 Stinger surface-to-air missiles,[160] to Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI)—which funneled them to tens of thousands of Afghan mujahideen resistance fighters in order to fight the Soviets and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan during the Soviet-Afghan War.[161][162][163] In total, the CIA sent approximately 2,300 Stingers to Afghanistan, creating a substantial black market for the weapons throughout the Middle East, Central Asia, and even parts of Africa that persisted well into the 1990s. Perhaps 100 Stingers were acquired by Iran. The CIA later operated a program to recover the Stingers through cash buybacks.[164]

Nicaragua

[edit]Under President Jimmy Carter, the CIA was conducting covertly funded support for the Contras in their war against the Sandinistas. In March 1981, Reagan told Congress that the CIA would protect El Salvador by preventing the Sandinistas from shipping arms to communist rebels in El Salvador. The CIA also began arming and training the Contras in Honduras in hopes that they could depose the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.[165] The CIA was involved in the Iran–Contra affair arms smuggling scandal. Repercussions from the scandal included the creation of the Intelligence Authorization Act in 1991. It defined covert operations as secret missions in geopolitical areas where the U.S. is neither openly nor apparently engaged. This also required an authorizing chain of command, including an official, presidential finding report and the informing of the House and Senate Intelligence Committees, which, in emergencies, requires only "timely notification." Critics have alleged that the CIA was also involved in Contra cocaine trafficking.[166][167]

Lebanon

[edit]The CIA's prime source in Lebanon was Bashir Gemayel, a member of the Christian Maronite sect. The uprising against the Maronite minority blindsided the CIA. Israel invaded Lebanon, and, along with the CIA, propped up Gemayel. This secured Gemayel's assurance that Americans would be protected in Lebanon. Thirteen days later he was assassinated. Imad Mughniyah, a Hezbollah assassin, targeted Americans in retaliation for the Israeli invasion, the Sabra and Shatila massacre, and the US Marines of the Multi-National Force for their role in opposing the PLO in Lebanon. On April 18, 1983, a 2,000 lb car bomb exploded in the lobby of the American embassy in Beirut, killing 63 people, including 17 Americans and 7 CIA officers, including Robert Ames, one of the CIA's Middle East experts. America's fortunes in Lebanon suffered more as America's poorly directed retaliation for the bombing was interpreted by many as support for the Maronite minority. On October 23, 1983, two bombs (1983 Beirut Bombing) were set off in Beirut, including a 10-ton bomb at a US military barracks that killed 242 people.

The embassy bombing killed Ken Haas, the CIA's Station Chief in Beirut. Bill Buckley was sent in to replace him. Eighteen days after the US Marines left Lebanon, Buckley was kidnapped. On March 7, 1984, Jeremy Levin, CNN's Bureau Chief in Beirut, was kidnapped. Twelve more Americans were captured in Beirut during the Reagan Administration. Manucher Ghorbanifar, a former Savak agent, was an information seller, and was discredited over his record of misinformation. He reached out to the agency offering a back channel to Iran, suggesting a trade of missiles that would be lucrative to the intermediaries.[168]

Pakistan

[edit]It has been alleged by such authors as Ahmed Rashid that the CIA and ISI have been waging a clandestine war.

India–Pakistan geopolitical tensions

[edit]On May 11, 1998, CIA Director George Tenet and his agency were taken aback by India's second nuclear test. The test prompted concerns from its nuclear-capable adversary, Pakistan, and, "remade the balance of power in the world." The nuclear test was New Delhi's calculated response to Pakistan previously testing new missiles in its expanding arsenal. This series of events subsequently revealed the CIA's "failure of espionage, a failure to read photographs, a failure to comprehend reports, a failure to think, and a failure to see."[169]

Poland, 1980–1989

[edit]Unlike the Carter administration, the Reagan administration supported the Solidarity movement in Poland, and – based on CIA intelligence – waged a public relations campaign to deter what the Carter administration felt was "an imminent move by large Soviet military forces into Poland." Colonel Ryszard Kukliński, a senior officer on the Polish General Staff, was secretly sending reports to the CIA.[170]

The CIA transferred around $2 million yearly in cash to Solidarity, which suggests that $10 million total is a reasonable estimate for the five-year total. There were no direct links between the CIA and Solidarność, and all money was channeled through third parties.[171] CIA officers were barred from meeting Solidarity leaders, and the CIA's contacts with Solidarność activists were weaker than those of the AFL–CIO, which raised 300 thousand dollars from its members, which were used to provide material and cash directly to Solidarity, with no control of Solidarity's use of it. The U.S. Congress authorized the National Endowment for Democracy to promote democracy, and the NED allocated $10 million to Solidarity.[172]

When the Polish government launched a crackdown in December 1981, Solidarity was not alerted. Explanations for this vary; some believe the CIA was caught off guard, while others suggest that American policymakers viewed an internal crackdown as preferable to an "inevitable Soviet intervention."[173]

CIA support for Solidarity included money, equipment and training, which was coordinated by Special Operations CIA division.[174] Henry Hyde, U.S. House intelligence committee member, said that the U.S. provided "supplies and technical assistance in terms of clandestine newspapers, broadcasting, propaganda, money, organizational help and advice".[175] Michael Reisman of Yale Law School named operations in Poland as one of the CIA's Cold War covert operations.[176]

Initial funds for covert actions by the CIA were $2 million, but authorization was soon increased and by 1985 the CIA had successfully infiltrated Poland.[177] Rainer Thiel, in Nested Games of External Democracy Promotion: The United States and the Polish Liberalization 1980–1989, mentions how covert operations by the CIA, and spy games, among others, allowed the U.S. to proceed with successful regime change.[178]

Operation Gladio

[edit]During the Cold War, the CIA and NATO were involved in Operation Gladio.[179][180] As part of Operation Gladio, the CIA supported the Italian government, and allegedly supported neo-fascist organizations[181][182][183] such as National Vanguard, New Order and the Nuclei Armati Rivoluzionari during the Years of Lead in Italy.

In Turkey, Gladio was called Counter-Guerrilla. CIA efforts strengthened the Pan-Turkist movement through the founding member of the Counter-Guerrilla; Alparslan Türkeş.[184] Other far-right individuals employed by the CIA as part of Counter-Guerilla included Ruzi Nazar, a former SS officer and Pan-Turkist.[185]

Operation Desert Storm

[edit]During the Iran–Iraq War, the CIA had backed both sides. The CIA had maintained a network of spies in Iran, but in 1989 a CIA mistake compromised every agent they had in there, and the CIA had no agents in Iraq. In the weeks before the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the CIA downplayed the military buildup. During the war, CIA estimates of Iraqi abilities and intentions flip-flopped and were rarely accurate. In one particular case, the DOD had asked the CIA to identify military targets to bomb. One target the CIA identified was an underground shelter. The CIA did not know that it was a civilian bomb shelter. In a rare instance, the CIA correctly determined that the coalition forces efforts were coming up short in their efforts to destroy SCUD missiles. Congress took away the CIA's role in interpreting spy-satellite photos, putting the CIA's satellite intelligence operations under the auspices of the military. The CIA created its office of military affairs, which operated as "second-echelon support for the Pentagon. .. answering ... questions from military men [like] 'how wide is this road?'"[186]

Fall of the Soviet Union

[edit]Mikhail Gorbachev's announcement of the unilateral reduction of 500,000 Soviet troops took the CIA by surprise. Moreover, Doug MacEachin, the CIA's Chief of Soviet analysis, said that even if the CIA had told the President, the NSC, and Congress about the cuts beforehand, it would have been ignored. "We never would have been able to publish it."[187] All the CIA numbers on the Soviet Union's economy were wrong. Too often the CIA relied on inexperienced people supposedly deemed experts. Bob Gates had preceded Doug MacEachin as Chief of Soviet analysis, and he had never visited the Soviet Union. Few officers, even those stationed in the country, spoke the language of the people on whom they spied. And the CIA could not send agents to respond to developing situations. The CIA analysis of Russia during the Cold War was either driven by ideology, or by politics. William J. Crowe, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, noted that the CIA "talked about the Soviet Union as if they weren't reading the newspapers, much less developed clandestine intelligence."[188]

On January 25, 1993, Mir Qazi opened fire at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, killing two officers and wounding three others.[189] On February 26, Al-Qaeda terrorists led by Ramzi Yousef bombed the parking garage below the North Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing six people and injuring 1,402 others.

During the Bosnian War, the CIA ignored signs within and without[clarification needed] of the Srebrenica massacre. On July 13, 1995, when the press report about the massacre came out, the CIA received pictures from a spy satellite of prisoners guarded by men with guns in Srebrenica.[190] The CIA had no agents on the ground to verify the report. Two weeks after news reports of the slaughter, the CIA sent a U-2 to photograph it. A week later the CIA completed its report on the matter. The final report came to the Oval Office on August 4, 1995. In short, it took three weeks for the agency to confirm that one of the largest mass murders in Europe since the Second World War had occurred.[190] Another CIA mistake which occurred in the Balkans during the Clinton presidency was the NATO bombing of Serbia. To force Slobodan Milošević to withdraw his troops from Kosovo, the CIA had been invited to provide military targets for bombings, wherein the agency's analysts used tourist maps to determine the location.[191] However, the agency incorrectly provided the coordinates of the Chinese Embassy as a target resulting in its bombing. The CIA had misread the target as Slobodan Milosevic's military depot.[192]

In Guatemala, the CIA produced the Murphy Memo, based on audio recordings made by covert listening devices planted by Guatemalan intelligence in the bedroom of Ambassador Marilyn McAfee. In the recording, Ambassador McAfee verbally entreated "Murphy." The CIA circulated a memo in the highest Washington circles accusing Ambassador McAfee of having an extramarital lesbian affair with her secretary, Carol Murphy. There was no affair. Ambassador McAfee was calling to Murphy, her poodle.[193]

Harold James Nicholson would burn[clarification needed] several serving officers and three years of trainees before he was caught spying for Russia. In 1997 the House would pen another report, which said that CIA officers know little about the language or politics of the people they spy on; the conclusion was that the CIA lacked the "depth, breadth, and expertise to monitor political, military, and economic developments worldwide."[194] Russ Travers said in the CIA in-house journal that in five years "intelligence failure is inevitable".[195] In 1997 the CIA's new director George Tenet would promise a new working agency by 2002. The CIA's surprise at India's detonation of an atom bomb was a failure at almost every level. After the 1998 embassy bombings by Al Qaeda, the CIA offered two targets to be hit in retaliation. One of them was the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory, where traces of chemical weapon precursors had been detected. In the aftermath, it was concluded that "the decision to target al Shifa continues a tradition of operating on inadequate intelligence about Sudan." It triggered the CIA to make "substantial and sweeping changes" to prevent "a catastrophic systemic intelligence failure."[196]

Aldrich Ames

[edit]Between 1985 and 1986, the CIA lost every spy it had in Eastern Europe. The details of the investigation into the cause were obscured from the new Director, and the investigation had little success and has been widely criticized. On February 21, 1994, FBI agents pulled Aldrich Ames out of his Jaguar.[197] In the investigation that ensued, the CIA discovered that many of the sources for its most important analyses of the USSR were based on Soviet disinformation fed to the CIA by controlled agents. On top of that, it was discovered that, in some cases, the CIA suspected at the time that the sources were compromised, but the information was sent up the chain as genuine.[198][199]

Osama bin Laden

[edit]Agency files show that it is believed Osama bin Laden was funding the Afghan rebels against the USSR in the 1980s.[200] In 1991, bin Laden returned to his native Saudi Arabia protesting the presence of troops, and Operation Desert Storm. He was expelled from the country. In 1996, the CIA created a team to hunt bin Laden. They were trading information with the Sudanese until, on the word of a source that would later be found to be a fabricator, the CIA closed its Sudan station later that year. In 1998, bin Laden would declare war on America, and, on August 7, strike in Tanzania and Nairobi. On October 12, 2000, Al Qaeda bombed the USS Cole. In the first days of George W. Bush's presidency, Al Qaeda threats were ubiquitous in daily presidential CIA briefings, but it may have become a case of false alarm. The agency's predictions were dire but carried little weight, and the focus of the president and his defense staff were elsewhere. The CIA arranged the arrests of suspected Al Qaeda members through cooperation with foreign agencies, but the CIA could not definitively say what effect these arrests have had, and it could not gain hard intelligence from those captured. The President had asked the CIA if Al Qaeda could plan attacks in the US. On August 6, Bush received a daily briefing with the headline, not based on current, solid intelligence, "Al Qaeda determined to strike inside the US." The US had been hunting bin Laden since 1996 and had had several opportunities, but neither Clinton, nor Bush had wanted to risk taking an active role in a murky assassination plot, and the perfect opportunity had never materialized for a DCI that would have given him the reassurances he needed to take the plunge. That day, Richard A. Clarke sent National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice warning of the risks, and decrying the inaction of the CIA.[201]

Al-Qaeda and the Global War on Terrorism

[edit]

In January 1996, the CIA created an experimental "virtual station," the Bin Laden Issue Station, under the Counterterrorist Center, to track bin Laden's developing activities. Al-Fadl, who defected to the CIA in spring 1996, began to provide the Station with a new image of the Al Qaeda leader: he was not only a terrorist financier but a terrorist organizer as well. FBI Special Agent Dan Coleman (who together with his partner Jack Cloonan had been "seconded" to the bin Laden Station) called him Qaeda's "Rosetta Stone".[202]

In 1999, CIA chief George Tenet launched a plan to deal with al-Qaeda. The Counterterrorist Center, its new chief, Cofer Black, and the center's bin Laden unit were the plan's developers and executors. Once it was prepared, Tenet assigned CIA intelligence chief Charles E. Allen to set up a "Qaeda cell" to oversee its tactical execution.[203] In 2000, the CIA and USAF jointly ran a series of flights over Afghanistan with a small remote-controlled reconnaissance drone, the Predator; they obtained probable photos of bin Laden. Cofer Black and others became advocates of arming the Predator with missiles to try to assassinate bin Laden and other al-Qaeda leaders.

September 11 attacks and its aftermath

[edit]

On September 11, 2001, 19 Al-Qaeda members hijacked four passenger jets within the Northeastern United States in a series of coordinated terrorist attacks. Two planes crashed into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, the third into the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia, and the fourth inadvertently into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. The attacks cost the lives of 2,996 people (including the 19 hijackers), caused the destruction of the Twin Towers, and damaged the western side of the Pentagon. Soon after 9/11, The New York Times released a story stating that the CIA's New York field office was destroyed in the wake of the attacks. According to unnamed CIA sources, while first responders, military personnel and volunteers were conducting rescue efforts at the World Trade Center site, a special CIA team was searching the rubble for both digital and paper copies of classified documents. This was done according to well-rehearsed document recovery procedures put in place after the Iranian takeover of the United States Embassy in Tehran in 1979.

While the CIA insists that those who conducted the attacks on 9/11 were not aware that the agency was operating at 7 World Trade Center under the guise of another (unidentified) federal agency, this center was the headquarters for many notable criminal terrorism investigations. Though the New York field offices' main responsibilities were to monitor and recruit foreign officials stationed at the United Nations, the field office also handled the investigations of the August 1998 bombings of United States Embassies in East Africa and the October 2000 bombing of the USS Cole.[204] Despite the fact that the 9/11 attacks may have damaged the CIA's New York branch, and they had to loan office space from the US Mission to the United Nations and other federal agencies, there was an upside for the CIA.[204] In the months immediately following 9/11, there was a huge increase in the number of applications for CIA positions. According to CIA representatives that spoke with The New York Times, pre-9/11 the agency received approximately 500 to 600 applications a week, in the months following 9/11 the agency received that number daily.[205]

The intelligence community as a whole, and especially the CIA, were involved in presidential planning immediately after the 9/11 attacks. In his address to the nation at 8:30pm on September 11, 2001, George W. Bush mentioned the intelligence community: "The search is underway for those who are behind these evil acts, I've directed the full resource of our intelligence and law enforcement communities to find those responsible and bring them to justice."[206]

The involvement of the CIA in the newly coined "War on Terror" was further increased on September 15, 2001. During a meeting at Camp David George W. Bush agreed to adopt a plan proposed by CIA director George Tenet. This plan consisted of conducting a covert war in which CIA paramilitary officers would cooperate with anti-Taliban guerrillas inside Afghanistan. They would later be joined by small special operations forces teams which would call in precision airstrikes on Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters. This plan was codified on September 16, 2001, with Bush's signature of an official Memorandum of Notification that allowed the plan to proceed.[207]

On November 25–27, 2001, Taliban prisoners revolted at the Qala Jangi prison west of Mazar-e-Sharif. Though several days of struggle occurred between the Taliban prisoners and the Northern Alliance members present, the prisoners gained the upper hand and obtained North Alliance weapons. At some point during this period Johnny "Mike" Spann, a CIA officer sent to question the prisoners, was beaten to death. He became the first American to die in combat in the war in Afghanistan.[207]

After 9/11, the CIA came under criticism for not having done enough to prevent the attacks. Tenet rejected the criticism, citing the agency's planning efforts especially over the preceding two years. He also considered that the CIA's efforts had put the agency in a position to respond rapidly and effectively to the attacks, both in the "Afghan sanctuary" and in "ninety-two countries around the world".[208][209] The new strategy was called the "Worldwide Attack Matrix".[210]

Anwar al-Awlaki, a Yemeni American U.S. citizen and al-Qaeda member, was killed on September 30, 2011, by a CIA drone strike in Yemen.[211][212] Al-Awlaki's 16-year-old son, a noncombatant and U.S. citizen, was also killed in a separate strike.[212] Although approved by the Department of Justice, the strikes sparked discussion on the legality of killing American citizens without trial.[211]

Failures in intelligence analysis

[edit]A major criticism is a failure to forestall the September 11 attacks. The 9/11 Commission Report identified failures in the IC as a whole. One problem, for example, was the FBI failing to "connect the dots" by sharing information among its decentralized field offices.

The report concluded that former DCI George Tenet failed to adequately prepare the agency to deal with the danger posed by al-Qaeda prior to the attacks of September 11, 2001.[213] The report was finished in June 2005 and was partially released to the public in an agreement with Congress, over the objections of current DCI General Michael Hayden. Hayden said its publication would "consume time and attention revisiting ground that is already well plowed."[214] Tenet disagreed with the report's conclusions, citing his planning efforts vis-à-vis al-Qaeda, particularly from 1999.[215] Assistant Secretary of State for Intelligence, Carl W. Ford Jr. remarked, "As long as we rate intelligence more for its volume than its quality, we will continue to turn out the $40 billion pile of crap we have become famous for." He further stated, "[The CIA is] broken. It's so broken that nobody wants to believe it."[216]

Yugoslav wars

[edit]In 1989; Yugoslavia officially dissolved into six republics, with borders drawn along ethnic and historical lines: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia. This quickly dissolved into ethnic tensions between Serbs and other Balkan ethnicities. In 1991, the CIA predicted that tension in the region would evolve into a full blown Civil war.[217] In 1992, the U.S. embargoed the trafficking of weapons into both Bosnia and Serbia in order to not prolong the war and the destruction of impacted communities. In May 1994, the CIA reported that the embargo had been ignored by countries such as Malaysia and Iran who moved weapons into Bosnia.[218]

Iraq War

[edit]Seventy-two days after the 9/11 attacks, President Bush told Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld to update the US plan for an invasion of Iraq, but not to tell anyone. Rumsfeld asked Bush if he could bring DCI Tenet into the loop, to which Bush agreed.[219]

The CIA had put eight of their best officers in Kurdish territory in Northern Iraq. By December 2002, the CIA had close to a dozen functional networks in Iraq[219]: 242 and would penetrate Iraq's SSO, tap the encrypted communications of the Deputy Prime Minister, and recruit the bodyguard of Hussein's son[which?] as an agent. As time passed, the CIA would become more frantic about the possibility of their networks being compromised. To the CIA, the invasion had to occur before the end of February 2003 if their sources inside Hussein's government were to survive. The rollup would happen as predicted; 37 CIA sources recognized by their Thuraya satellite telephones provided for them by the CIA.[219]: 337

The case Colin Powell presented before the United Nations (purportedly proving an Iraqi WMD program) was inaccurate. DDCI John E. McLaughlin was part of a long discussion in the CIA about equivocation. McLaughlin, who would make, among others, the "slam dunk" presentation to the President, "felt that they had to dare to be wrong to be clearer in their judgments".[219]: 197 The Al Qaeda connection, for instance, was from a single source, extracted through torture, and was later denied. The sole source for the allegations of Iraqi mobile weapons laboratories, code-named Curveball, was a known liar.[221] A postmortem of the intelligence failures in the lead up to Iraq led by former DDCI Richard Kerr would conclude that the CIA had been a casualty of the Cold War, wiped out in a way "analogous to the effect of the meteor strikes on the dinosaurs."[222]

The opening days of the invasion of Iraq would see successes and defeats for the CIA. With its Iraq networks compromised, and its strategic and tactical information shallow, and often wrong, the intelligence side of the invasion itself would be a black eye for the agency. The CIA would see some success with its "Scorpion" paramilitary teams composed of CIA Special Activities Division paramilitary officers, along with friendly Iraqi partisans. CIA SAD officers would also help the US 10th Special Forces.[219][223][224] The occupation of Iraq would be a low point in the history of the CIA. At the largest CIA station in the world, officers would rotate through 1–3-month tours. In Iraq, almost 500 transient officers would be trapped inside the Green Zone while Iraq station chiefs would rotate with only a little less frequency.[225]

2004, DNI takes over CIA top-level functions

[edit]The Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 created the office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), who took over some of the government and intelligence community (IC)-wide functions that had previously been the CIA's.[226] The DNI manages the United States Intelligence Community and in so doing it manages the intelligence cycle. Among the functions that moved to the DNI were the preparation of estimates reflecting the consolidated opinion of the 16 IC agencies, and preparation of briefings for the president. On July 30, 2008, President Bush issued Executive Order 13470[227] amending Executive Order 12333 to strengthen the role of the DNI.[228]

Previously, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) oversaw the Intelligence Community, serving as the president's principal intelligence advisor, additionally serving as head of the CIA. The DCI's title now is "Director of the Central Intelligence Agency" (D/CIA), serving as head of the CIA.

Currently, the CIA reports to the Director of National Intelligence. Before the establishment of the DNI, the CIA reported to the President, with informational briefings to congressional committees. The National Security Advisor is a permanent member of the National Security Council, responsible for briefing the President with pertinent information collected by all U.S. intelligence agencies, including the National Security Agency, the Drug Enforcement Administration, etc. All 16 Intelligence Community agencies are under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence.

Operation Neptune Spear

[edit]On May 1, 2011, President Barack Obama announced that Osama bin Laden was killed earlier that day by "a small team of Americans" operating in Abbottabad, Pakistan, during a CIA operation.[229][230] The raid was executed from a CIA forward base in Afghanistan by elements of the U.S. Navy's Naval Special Warfare Development Group and CIA paramilitary operatives.[231]

The operation was a result of years of intelligence work that included the CIA's capture and interrogation of Khalid Sheik Mohammad, which led to the identity of a courier of bin Laden's,[232][233][234] the tracking of the courier to the compound by Special Activities Division paramilitary operatives and the establishing of a CIA safe house to provide critical tactical intelligence for the operation.[235][236][237]