Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Princely Abbey of Fulda

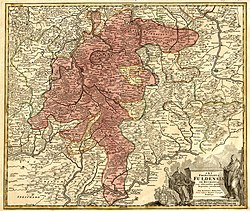

View on WikipediaThe Abbey of Fulda (German: Kloster Fulda; Latin: Abbatia Fuldensis), from 1221 the Princely Abbey of Fulda (Fürstabtei Fulda) and from 1752 the Prince-Bishopric of Fulda (Fürstbistum Fulda), was a Benedictine abbey and ecclesiastical principality centered on Fulda, in the present-day German state of Hesse.

Key Information

The monastery was founded in 744 by Saint Sturm, a disciple of Saint Boniface. After Boniface was buried at Fulda, it became a prominent center of learning and culture in Germany, and a site of religious significance and pilgrimage through the 8th and 9th centuries. The Annals of Fulda, one of the most important sources for the history of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century, were written there. In 1221 the abbey was granted an imperial estate to rule and the abbots were thereafter princes of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1356, Emperor Charles IV bestowed the title "Archchancellor of the Empress" (Erzkanzler der Kaiserin) on the prince-abbot. The growth in population around Fulda resulted in its elevation to a prince-bishopric in the second half of the 18th century.

Although the abbey was dissolved in 1802 and its principality was secularized in 1803, the diocese of Fulda continues to exist.

History

[edit]Carolingian period

[edit]In the mid-8th century, Saint Boniface commissioned Saint Sturm to establish a larger church than any other founded by Boniface. In January 744, Saint Sturm selected an unpopulated plot along the Fulda River, and shortly after obtained rights to the land. The foundation of the monastery dates to March 12, 744. Sturm travelled to notable monasteries of Italy, such as that of Monte Cassino, for inspiration in creating a monastery of such grand size and splendor. Boniface was proud of Fulda, and he obtained autonomy for the monastery from the bishops of the area by appealing to Pope Zachary for placement directly under the Holy See in 751. Boniface was entombed at Fulda following his martyrdom in 754 in Frisia, as per his request, creating a destination for pilgrimage in Germany and increasing its holy significance. Saint Sturm was named the first abbot of the newly established monastery, and led Fulda through a period of rapid growth.[1]

The monks of Fulda practiced many specialized trades, and much production took place in the monastery. Production of manuscripts increased the size of the library of Fulda, while skilled craftsmen produced many goods that made the monastery a financially wealthy establishment. As Fulda grew, members of the monastery moved from the main building and established villages in the outlying territories to connect with non-monastery members. They established themselves based on trade and agriculture, while still remaining connected to the monastery. Together, the monks of Fulda created a substantial library, financially stable production, and an effective centre for education.[1] In 774, Carloman placed Fulda under his direct control to ensure its continued success. Fulda was becoming an important cultural center to the Carolingian Empire, and Carloman hoped to ensure the continued salvation of his population through the religious activity of Fulda.[2]

The school at the Fulda monastery became a major focus of the monks under Sturm's successor, Abbot Baugulf, at the turn of the century. It contained an inner school for Christian studies, and an outer school for secular, including pupils who were not necessarily members of the monastery. During Boniface's lifetime he had sent the teachers of Fulda to apprentice under notable scholars in Franconia, Bavaria, and Thuringia, who returned with knowledge and texts of the sciences, literature, and theology. In 787 Charlemagne praised Fulda as a model school for others, leading by example in educating the public in secular and ecclesiastical matters.[1]

Around the year 807, an epidemic claimed much of Fulda's population.[3] During this time, the third abbot of Fulda, Ratgar, was carrying out construction on a new church started by Baugulf.[4] According to the "Supplex Libellus", an account of Fulda's history written by the monks, Ratgar was overzealous, exiling monks opposed to the excessive attention being given to the new church, and punishing those attempting to flee the epidemic that was spreading amongst the population. This prompted a discussion in Fulda as to how the monastery was to be properly run, and the nature of the responsibilities of the monks.[5]

Until this point, a focus of the monks had been remembering and recording the lives of the deceased, specifically those who were members of the Fulda monastery, in what was known as the "Annales Necrologici".[6] They sang psalms for their dead to ensure their eternal salvation. Under Ratgar, the focus of the monastery had shifted to that of construction and arbitrary regulation; monks were being exiled for questionable reasons, or punished in seemingly unjust ways. Another matter of concern included who was permitted into the inner monastery; Ratgar was at the time hosting a criminal in the living quarters. The concept of private and public property was also in contention. With the land of Fulda expanding, the monks desired all property to be public rather than create a contention for private land, while Ratgar opposed this perspective. The "Supplex Libellus" also attempted to address the issue of the growing secular responsibilities of the monastery. As the school grew and the communities around Fulda expanded, the monastery was feeling the strain of balancing ecclesiastical obligations with its newfound secular prominence. The monks were successful in their grievances against Ratgar, and Louis the Pious sympathized with them. Agreeing that Ratgar's plans were too ambitions for Fulda, and his punishments too extensive, he exiled Ratgar from Fulda in 817, and Eigil became the fourth Abbot of Fulda.[4]

Under Abbot Eigil's leadership, construction of the new church continued at a more moderate pace. He sought to stylize the church after St. Peter's in Rome, adding a notable western transept in the same fashion. The transept was a new architectural style, and in mimicking it, Fulda demonstrated their support to the papacy through tribute. This unique architectural tie, as well as the growing intellectual importance of Fulda, created strong ties with the Roman papacy. Coupled with the tomb of Saint Boniface, Fulda attracted much religious pilgrimage and worship, a site of great significance.[citation needed]

In 822, Rabanus Maurus became the fifth abbot of Fulda. He was previously educated at the monastery, and was very academically inclined, becoming both a teacher and head-master at the school before becoming abbot. Understanding the importance of education, the school became the main focus of Fulda under his leadership, and he led Fulda to the height of its importance and success.[7] He established separate departments for the school, including those for sciences, theological studies, and the arts.[1] Rabanus made an effort to collect various additional holy relics and manuscripts of historical significance to Fulda and the surrounding the areas to fortify their prominence in the Frankish Empire.[8] With each relic, the significance of Fulda grew, and more gifts and power were bestowed upon the abbey. Power was, however, not Rabanus's only intent; the increased holiness of the lands also served to bring his monks and pilgrims closer to God.[9] The collection accumulated under Rabanus was largely lost during the looting of Fulda by the Hessians during the Thirty Years' War.[10]

Imperial principality

[edit]Succeeding abbots carried the monastery down the same path, with Fulda retaining a place of prominence in the German territories. With the decline of the Carolingian rule, Fulda lost its security and relied increasingly on patronage from independent sources.[11] The abbot of Fulda held the position of primate over all Benedictine monasteries in Germany for several centuries. From 1221 and onwards, the abbots also served as Princes of the Holy Roman Empire, given this rank by Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, and resulted in increased secular as well as monastic obligations. The increased importance of Fulda resulted in much patronage and wealth; as a result, the wealthy and noble eventually made up the majority of the abbey's population. The wealthy monks used their positions for their own means, going as far as to attempt to turn monastic lands into their own private property. This caused great unrest by the 14th century, and Count Johann con Ziegenhain led an insurrection, alongside other citizens of Fulda, against Prince-Abbot Heinrich VI, 55th abbot of the monastery. The combination of responsibilities to the empire and corruption of traditional monastic ideals, so highly valued by Boniface and the early abbots, placed great strain on the monastery and its school.[10]

In the later Middle Ages, a dean of the monastic school functionally replaced the abbot concerning scholastic management, once more granting it relative independence concerning ecclesiastical functions of Fulda. However, the monastery (and surrounding city) would never regain its status as a great cultural center it once held during the early medieval years. The monastery was dissolved in 1802. The spiritual principality was secularized in 1803 after the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss, but the episcopal see continued.[10]

The secular territory of Fulda was joined the Principality of Orange-Nassau along with several other mediatized lands to form the Principality of Nassau-Orange-Fulda. Prince William Frederick refused to join the Confederation of the Rhine and, following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in August 1806, fled to Berlin. Fulda was taken over by the French. In 1810 it was given to the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt, but was occupied by Austria from 1813 and by Prussia from 1815. the Congress of Vienna resurrected it as the Grand Duchy of Fulda and gave it to the Electorate of Hesse in 1815.[12]

Library and scriptorium

[edit]The library held approximately 2000 manuscripts. It preserved works such as Tacitus' Annales, Ammianus Marcellinus' Res gestae, and the Codex Fuldensis which has the reputation of serving as the cradle of Old High German literature. It was probably here that an Italian book-hunter in 1417 discovered the last surviving manuscript of Lucretius's De Rerum Natura, which then became enormously influential in humanist circles. Its abundant records are conserved in the state archives at Marburg. As of 2013[update] the Fulda manuscripts have become widely dispersed; some have found their way to the Vatican Library.

A notable work that the monks of Fulda produced was the "Annales necrologici", a list of all the deceased members of the abbey following the death of Saint Sturm in 744.[13] The monks offered prayer for the dead listed in the Annales to ensure their eternal salvation. While at first this record only contained the names of those at Fulda, as the power and prominence of Fulda grew, so too did the scope of who was to be included in the Annales. Patrons, citizens, and nobles of the area all came to be recorded in this piece of Fulda and its concept of community. The documenting of dates of passing, beginning with Sturm, created a sense of continuity and a reference for the passage of time for the monks of Fulda.[6]

List of rulers

[edit]

Abbots

[edit]- Saint Sturm 744-779

- Baugulf 779-802

- Ratgar 802-817

- Eigil 818-822

- Rabanus Maurus 822-842

- Hatto I. 842-856

- Thioto 856-869

- Sigihart 869-891

- Huoggi 891-915

- Helmfried 915-916

- Haicho 917-923

- Hiltibert 923-927

- Hadamar 927-956

- Hatto II. 956-968

- Werinheri 968-982

- Branthoh I. 982-991

- Hatto III. 991-997

- Erkanbald 997–1011

- Branthoh II. 1011–1013

- Poppo 1013–1018, also Abbot of Lorsch (Franconian Babenberger)

- Richard 1018–1039

- Sigiwart 1039–1043

- Rohing 1043–1047

- Egbert 1047–1058

- Siegfried von Eppenstein 1058–1060, also Archbishop of Mainz

- Widerad von Eppenstein 1060–1075

- Ruothart 1075–1096

- Godefrid 1096–1109

- Wolfhelm 1109–1114

- Erlolf von Bergholz 1114–1122

- Ulrich von Kemnaten 1122–1126

- Heinrich I. von Kemnaten 1126–1132

- Bertho I. von Schlitz 1132–1134

- Konrad I. 1134–1140

- Aleholf 1140–1148

- Rugger I. 1148

- Heinrich II. von Bingarten 1148–1149

- Markward I. 1150–1165

- Gernot von Fulda 1165

- Hermann 1165–1168

- Burchard Graf von Nürings 1168–1176

- Rugger II. 1176–1177

- Konrad II. 1177–1192

- Heinrich III. von Kronberg im Taunus 1192–1216

- Hartmann I. 1216–1217

- Kuno 1217–1221

Prince-Abbots

[edit]- Konrad III. von Malkes 1221–1249

- Heinrich IV. von Erthal 1249–1261

- Bertho II. von Leibolz 1261–1271

- Bertho III. von Mackenzell 1271–1272

- Bertho IV. von Biembach 1273–1286

- Markward II. von Bickenbach 1286–1288

- Heinrich V. Graf von Weilnau 1288–1313

- Eberhard von Rotenstein 1313–1315

- Heinrich VI. von Hohenberg 1315–1353

- Heinrich VII. von Kranlucken 1353–1372

- Konrad IV. Graf von Hanau 1372–1383

- Friedrich I. von Romrod 1383–1395

- Johann I. von Merlau 1395–1440

- Hermann II. von Buchenau 1440–1449

- Reinhard Graf von Weilnau 1449–1472

- Johann II. Graf von Henneberg-Schleusingen 1472–1513

- Hartmann II. Burggraf von Kirchberg 1513–1521/29

- Johann III. Graf von Henneberg-Schleusingen 1521/29–1541

- Philipp Schenk zu Schweinsberg 1541–1550

- Wolfgang Dietrich von Eusigheim 1550–1558

- Wolfgang Schutzbar (named Milchling) 1558–1567

- Philipp Georg Schenk zu Schweinsberg 1567–1568

- Wilhelm Hartmann von Klauer zu Wohra 1568–1570

- Balthasar von Dernbach, 1570–1606 (exiled 1576–1602)

- Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn, Bishop of Würzburg, administrator 1576–1602

- Johann Friedrich von Schwalbach 1606–1622

- Johann Bernhard Schenk zu Schweinsberg 1623–1632

- Johann Adolf von Hoheneck 1633–1635

- Hermann Georg von Neuhof (named Ley) 1635–1644

- Joachim Graf von Gravenegg 1644–1671

- Cardinal Gustav Adolf (Baden) (Bernhard Gustav Markgraf von Baden-Durlach) 1671–1677

- Placidus von Droste 1678–1700

- Adalbert I. von Schleifras 1700–1714

- Konstantin von Buttlar 1714–1726

- Adolphus von Dalberg 1726–1737

- Amand von Buseck, 1737–1756, Prince-Bishop after 1752

Prince-Bishops/Prince-Abbots

[edit]

- Adalbert II. von Walderdorff 1757–1759

- Heinrich VIII. von Bibra, 1759–1788

- Adalbert von Harstall, 1789–1802, remained bishop until 1814

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d (1878). "The Monastery of Fulda". The Catholic World, A Monthly Magazine of General Literature and Science, 28 (165). 301-309.

- ^ Raaijmakers, J. E. (2003). Sacred time, sacred space, history and identity in the monastery of Fulda. Amsterdam: In eigen beheer. 1-20.

- ^ Raaijmakers. Sacred time, sacred space, history and identity in the monastery of Fulda. 57-92

- ^ a b Raaijmakers. Sacred time, sacred space, history and identity in the monastery of Fulda. 93–134

- ^ Raaijmakers. Sacred time, sacred space, history and identity in the monastery of Fulda. 57-92.

- ^ a b Raaijmakers. Sacred time, sacred space, history and identity in the monastery of Fulda. 21-56

- ^ Ott, M. (1911). "Blessed Maurus Magnentius Rabanus" in The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved October 20, 2013

- ^ Raaijmakers. Sacred time, sacred space, history and identity in the monastery of Fulda. 167-202

- ^ Raaijmakers, The Making of the Monastic Community of Fulda, c. 744 – c. 900. 227

- ^ a b c Lins, J. (1909). Fulda in The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved October 20, 2013

- ^ Raaijmakers. The Making of the Monastic Community of Fulda, c. 744 – c. 900. 265

- ^ Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der deutschen Länder: Die deutschen Territorien vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart (C. H. Beck, 2007), p. 203.

- ^ Raaijmakers, J. E. (2012) The Making of the Monastic Community of Fulda, c. 744 – c. 900. New York: Cambridge University Press. 292

Further reading

[edit]- Germania Benedictina, Bd.VII: Die benediktinischen Mönchs- und Nonnenklöster in Hessen, 1. Auflage 2004 St. Ottilien, S. 214–375 ISBN 3-8306-7199-7

External links

[edit]Princely Abbey of Fulda

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Foundation

Establishment by Saint Sturm in 744

Saint Sturm, also known as Sturmius, a disciple of the Anglo-Saxon missionary Saint Boniface, received instructions from Boniface in 744 to establish a Benedictine monastery in the region of northern Hesse, utilizing land granted to Boniface by Carloman, the Frankish mayor of the palace.[1] Sturm, born around 705 in Bavaria to a noble family, had previously assisted Boniface in missionary efforts, including the founding of the monastery at Fritzlar.[1] Tasked with selecting a suitable site amid dense forests and pagan territories, Sturm undertook an extensive search on horseback, eventually identifying a location at a ford on the Fulda River, near the ruins of a 6th-century Merovingian royal camp previously destroyed by Saxon incursions.[1] On March 12, 744, Sturm formally took possession of the site, erecting a cross to mark the beginning of Christian reclamation in the wilderness area.[1] [4] Construction of the monastery and church commenced promptly thereafter, with laborers clearing the forested terrain to lay foundations for monastic buildings.[1] Sturm served as the inaugural abbot, organizing the community according to the Benedictine Rule, which he later refined in 748 by traveling to Monte Cassino in Italy to study its practices firsthand, blending elements of Anglo-Saxon monastic traditions with those of the Italian mother house.[1] The establishment of Fulda marked a strategic expansion of Boniface's evangelization efforts in Germania, transforming a remote, pagan-held frontier into a center for Christian worship and learning, supported by royal Frankish patronage that ensured initial endowments of land and resources.[1] Early donations from Frankish nobles and locals facilitated rapid growth, positioning the abbey as a bulwark against Saxon resistance and a base for further missionary outreach.[4]Association with Saint Boniface and Missionary Role

The Princely Abbey of Fulda originated from the missionary endeavors of Saint Boniface, an Anglo-Saxon monk active in the Christianization of Germanic tribes during the 8th century. Boniface, tasked by Pope Gregory II in 719 with evangelizing pagans east of the Rhine, focused on regions like Hesse and Thuringia, where he established monastic foundations to support ongoing conversion efforts.[5] In 744, Sturm, one of Boniface's closest disciples, founded the abbey at Boniface's behest, selecting a forested site in the Fulda River valley for its seclusion conducive to monastic discipline.[1] Boniface personally approved the location and secured a land grant from Carloman, the Frankish mayor of the palace, while obtaining papal exemption from local episcopal oversight directly from Pope Zachary, ensuring the abbey's autonomy under the Holy See.[1] Boniface played a supervisory role in the abbey's early organization, introducing the Benedictine Rule and providing annual guidance to its community, which emphasized strict observance and scholarly pursuits as tools for missionary expansion.[5] Following Boniface's martyrdom on June 5, 754, during a baptismal mission in Frisia, his remains were transported to Fulda and interred there on June 16, 755, elevating the abbey to a primary cult site for his veneration and attracting pilgrims seeking his intercession.[6] This association transformed Fulda into a spiritual hub, with Boniface's relics symbolizing the triumph of Christian mission over pagan resistance in central Europe.[1] In its missionary capacity, Fulda functioned as a strategic base for extending Boniface's work, training monks in theology, liturgy, and Germanic linguistics to facilitate preaching and scripture translation among unconverted tribes.[6] The abbey dispatched communities to frontier areas, supporting the consolidation of Frankish alliances with newly baptized rulers and countering Saxon incursions through fortified ecclesiastical presence.[5] By preserving Boniface's letters and hagiographical accounts, Fulda documented these efforts, underscoring the causal link between monastic stability and sustained evangelization amid political volatility.[7]Historical Development

Carolingian Expansion and Royal Favor (8th-9th Centuries)

Following the initial establishment under Boniface's influence, the Abbey of Fulda experienced significant territorial and institutional expansion during the Carolingian era, as the dynasty consolidated power over key monastic institutions to support missionary efforts, administrative control, and cultural revival in newly Christianized regions. In 777, Charlemagne issued a charter confirming the abbey's existing possessions—derived from its founding grants—and awarding additional royal estates including Hammelburg, Eschenbach, Diebach, and Erthal, which bolstered its economic base through agricultural revenues and judicial rights over these lands.[8] These grants reflected a pattern of royal patronage, where abbeys like Fulda received immunities from local secular interference, allowing direct accountability to the king and enhancing their role as stable outposts in the Frankish frontier.[9] By the late 8th century, under Abbot Baugulf (r. 780–802), a former lay magnate rewarded for political loyalty to Charlemagne amid dynastic struggles, Fulda's holdings expanded further through strategic alliances and royal endorsements, positioning it as a proprietary monastery tied closely to Carolingian interests.[9] Royal favor extended to intellectual and ecclesiastical reforms, aligning Fulda with Charlemagne's vision for a unified Christian empire. In a letter to Baugulf circa 785–786, known as De litteris colendis, Charlemagne exhorted the abbot to prioritize literacy among monks and clergy, decrying the decline in scriptural knowledge and urging emulation of ancient models to produce competent administrators and teachers for the realm. This directive catalyzed Fulda's emergence as a hub of the Carolingian Renaissance, with its scriptorium producing illuminated manuscripts and the abbey dispatching scholars like Einhard to the palace school at Aachen.[10] The abbey's monks compiled the Annals of Fulda, a primary chronicle documenting Carolingian politics from 714 to 901, underscoring its archival importance to royal historiography.[11] Under Louis the Pious (r. 814–840), Fulda retained privileged status, with the emperor intervening in abbatial elections to ensure stability, as in 818 when he permitted the community to select Eigil (r. 817–822) after resolving internal disputes.[12] Abbot Hrabanus Maurus (r. 822–842), a pupil of Alcuin, further amplified this favor by reforming discipline, expanding the library to over 400 volumes, and founding dependencies like Hersfeld, while securing confirmations of immunities that shielded Fulda from episcopal oversight.[13] By the mid-9th century, amid Carolingian fragmentation, these privileges waned with the dynasty's decline, yet Fulda's accumulated lands—spanning hundreds of square kilometers—and direct royal ties had transformed it into a proto-princely entity, independent of local bishops and reliant on imperial protection for autonomy.[13]High Middle Ages: Imperial Abbey and Territorial Growth (10th-13th Centuries)

In the High Middle Ages, the Abbey of Fulda functioned as a prominent Reichskloster, or imperial abbey, enjoying direct subordination to the Holy Roman Emperor and exemption from episcopal oversight, a privilege originating in its Carolingian foundations and periodically reaffirmed through imperial charters. This status afforded the abbots substantial autonomy in ecclesiastical and temporal affairs, enabling them to administer vast estates without interference from regional bishops or counts. Emperor Henry II, for example, confirmed Fulda's existing privileges in a 1020 charter issued at the behest of Abbot Richard of Fulda, underscoring the abbey's enduring position within the imperial orbit and its role in supporting royal interests.[14] Territorial expansion accelerated during the tenth and eleventh centuries through a combination of imperial grants, monastic acquisitions, and the consolidation of proprietary rights over donated lands. By the early tenth century, Fulda's holdings had amassed significant fiefs capable of mobilizing up to 6,000 fighting men, reflecting the abbey's growing military obligations and economic leverage within the fragmented post-Carolingian landscape. These acquisitions built upon pre-900 endowments totaling hundreds of properties, with tenth-century grants further extending influence into East Franconia and the Middle Rhine regions, where abbots secured advocacies and judicial rights over dependent communities.[15] By the twelfth century, Fulda's abbots increasingly wielded influence in imperial administration, occasionally serving as chancellors and leveraging their position to negotiate additional territories, including allodial lands and servile estates. This period saw the abbey transition from dispersed monastic properties to a more unified territorial complex, as abbots invested in village foundations and fortified outposts to integrate peripheral holdings. The culmination of this growth occurred in the early thirteenth century, when Emperor Frederick II granted Fulda administrative rights over an imperial estate in 1221, formalizing the abbots' princely authority and embedding the abbey within the empire's collegiate structures.[16]Late Middle Ages: Internal Conflicts and Insurrections (14th-15th Centuries)

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the Princely Abbey of Fulda was marked by internal power struggles among the prince-abbot's administration, the noble canons of the cathedral chapter (Stiftsadel), and the burgeoning urban bourgeoisie, reflecting broader tensions over authority, resource allocation, and governance in an expanding ecclesiastical principality. These conflicts arose as the abbey sought to consolidate territorial control amid fiscal pressures from imperial obligations, local defense needs, and monastic maintenance, often imposing heavier taxes and corvées on dependent towns and villages. The chapter nobility, holding significant influence over abbatial elections and policy, frequently clashed with the abbot over appointments and land management, while burghers resented the abbey's seigneurial privileges that limited municipal self-rule.) A pivotal event was the 1331 uprising in the city of Fulda, where citizens protested escalating tax burdens that strained local economies and trade, demanding relief and greater representation against abbatial overreach. This insurrection, fueled by economic grievances and supported by elements of the local nobility, temporarily disrupted abbey authority and forced negotiations, though the prince-abbot ultimately suppressed it through imperial mediation and military reinforcement, reaffirming the abbey's feudal dominance. The event exemplified how fiscal policies, intended to sustain the abbey's independence within the Holy Roman Empire, provoked resistance from subjects accustomed to customary rights.) Tensions persisted into the 15th century, with intermittent disputes between the abbey and chapter over jurisdictional boundaries and revenue shares, occasionally escalating to legal appeals at imperial courts. Burgher unrest simmered, as ongoing taxation for abbey fortifications and diplomatic ventures—such as contributions to imperial diets—strained urban finances without commensurate benefits, foreshadowing the formation of representative estates by the early 16th century. These internal frictions weakened the abbey's cohesion but did not precipitate its dissolution, as prince-abbots leveraged alliances with regional powers to maintain order.)Princely Status and Governance

Elevation to Imperial Principality

In 1220, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II elevated the Imperial Abbey of Fulda to the status of a princely abbey (Fürstabtei), conferring upon its abbot the rank of prince of the Empire (Reichsfürst) with comprehensive territorial sovereignty. This act built upon the abbey's longstanding imperial immediacy, originally granted in 765 by Pepin the Short and reaffirmed by Charlemagne, which had exempted it from local episcopal oversight and placed it directly under imperial authority. The 1220 privilege explicitly empowered the abbot to govern Fulda's domains as a secular ruler, encompassing rights to exercise high and low justice, mint coins, levy tolls, and maintain fortifications and troops, thereby transforming the abbey into a hybrid ecclesiastical-temporal principality comparable to other major Hochstifte. The elevation occurred amid Frederick II's efforts to consolidate imperial support among loyal ecclesiastical institutions during conflicts with the Papacy and German princes, with Fulda's abbot Heinrich VI (r. 1208–1216) and successor Konrad I von Reisenberg (r. 1216–1221) securing these privileges through demonstrations of fidelity to the Hohenstaufen dynasty. By this point, Fulda controlled approximately 1,200 square kilometers of territory scattered across Hesse, Thuringia, and Franconia, including over 50 villages, castles like Rhönstein and Tracht, and judicial districts yielding significant revenues—estimated at around 20,000 marks annually by the 13th century from rents, tithes, and forests. This sovereignty extended to administrative autonomy, with the abbot appointing officials, convening estates, and defending borders against encroachments by neighbors such as the Landgraviate of Hesse.[3] As a result, Fulda's abbots gained a hereditary seat and vote in the bench of ecclesiastical princes (geistliche Fürstenbank) of the Imperial Diet (Reichstag), first exercised prominently in the 14th century, elevating the institution's influence in imperial politics and diplomacy. This status persisted through the Late Middle Ages, enabling abbots to navigate feuds, alliances, and reforms while balancing monastic rule under the Benedictine Rule with princely duties, though internal challenges like peasant unrest and noble rivalries periodically tested its cohesion. The principality's boundaries and privileges were further delineated in subsequent confirmations, such as by Emperor Charles IV in 1356, who reinforced Fulda's exemptions and territorial integrity against secular threats.Transition to Prince-Bishopric in 1752

On October 5, 1752, Pope Benedict XIV elevated the Princely Abbey of Fulda to the status of a bishopric, establishing the Diocese of Fulda and transforming its governance structure while preserving its Benedictine monastic foundation.[17][18] This papal bull granted the abbot episcopal dignity, enabling him to perform ordinations, consecrations, and other sacramental functions independently, which had previously necessitated appeals to external bishops such as those of Mainz or Würzburg.[19] The elevation reflected Fulda's expanded territorial holdings—encompassing approximately 1,000 square kilometers and a population exceeding 70,000 by the mid-18th century—and its role as a major ecclesiastical principality within the Upper Rhenish Circle of the Holy Roman Empire.[20] Amand von Buseck, who had served as prince-abbot since December 11, 1738, became the inaugural prince-bishop on November 27, 1752, following his episcopal consecration.[21] The monastic community transitioned into the role of a cathedral chapter, comprising one dean and twelve canons drawn from the monks, thereby maintaining the abbey's communal discipline under the bishop-abbot's dual authority.[19] This hybrid arrangement ensured continuity in spiritual and administrative practices, with the prince-bishop retaining imperial immediacy and secular princely rights, including jurisdiction over courts, taxation, and military obligations.[22] The transition strengthened Fulda's ecclesiastical autonomy amid Enlightenment-era reforms and imperial politics, allowing it to ordain clergy locally and assert metropolitan-like influence without subordinating to neighboring dioceses.[17] Buseck's tenure as prince-bishop until his death on December 4, 1756, focused on infrastructural improvements, including porcelain manufacturing initiatives begun in 1741, which bolstered the principality's economy.[23] Successors, such as Adalbert von Walderdorff (1757–1759) and Heinrich von Bibra (1759–1788), built on this foundation, navigating the abbey-bishopric toward prosperity until its secularization in 1803.[21]Cultural and Intellectual Center

Library, Scriptorium, and Preservation of Knowledge

The scriptorium of Fulda Abbey, established soon after the monastery's founding in 744, became a vital hub for manuscript production during the Carolingian era, where monks copied classical, patristic, and contemporary texts to support liturgical, scholarly, and administrative needs.[24] Under abbots such as Baugulf (780–802) and Ratgar (804–817), the scriptorium expanded, with Ratgar commissioning a dedicated library building to house growing collections, reflecting the abbey's integration into Charlemagne's cultural revival efforts.[10] This activity aligned with broader Carolingian reforms, producing works in the emerging Caroline minuscule script, which enhanced legibility and influenced European paleography.[25] The abbey's library grew substantially through scriptorial output and acquisitions, reaching approximately 2,000 manuscripts by its medieval peak, encompassing theological treatises, historical annals, and secular classics.[26] Key productions included the Annales Fuldenses, compiled in the 9th century as a primary chronicle of Carolingian events from 714 to 901, offering detailed accounts of imperial politics and ecclesiastical affairs.[10] During Hrabanus Maurus's abbacy (822–842), scholarly copying intensified, preserving patristic works by authors like Augustine and Jerome while fostering original compositions on grammar, encyclopedias, and biblical exegesis. Fulda played a crucial role in safeguarding ancient knowledge against losses from late antiquity's disruptions, housing manuscripts of Roman historians such as Tacitus's Annales (books 1–6, via a circa 1000 AD codex likely produced there) and Ammianus Marcellinus's Res Gestae.[27][26] The Codex Fuldensis, a 6th-century Vulgate Bible witness containing Victor of Capua's harmony of the Gospels, was also maintained, providing one of the earliest complete Latin scriptural texts and aiding textual criticism.[26] These efforts, sustained through the High Middle Ages, ensured transmission of secular historiography amid monastic priorities, though later dispersions during the Reformation and secularization in 1803 scattered holdings to archives like Marburg and the Vatican.[26] Despite such losses, Fulda's contributions underscore its function as a conduit for empirical historical records and classical causality in medieval Europe.Notable Figures and Scholarly Achievements

The monastic school at Fulda, established in the late 8th century under Abbot Baugulf (780–802), became a key center for Carolingian learning, producing prominent scholars such as Einhard, who received his early education there after 779 before being summoned to Charlemagne's court.[3][28] Einhard's training in manuscript copying and classical studies at Fulda laid the foundation for his later works, including the Vita Karoli Magni, the primary biography of Charlemagne, which drew on Fulda's emphasis on historical and rhetorical skills.[29] Hrabanus Maurus (c. 776–856), abbot from 822 to 842, stands as Fulda's most renowned scholarly figure, expanding the abbey's intellectual output through extensive writings on grammar, education, biblical exegesis, and theology.[1] His encyclopedic De Universo (c. 842–847), structured around the liberal arts and natural sciences, synthesized classical and patristic knowledge for monastic use, while his commentaries on Scripture and poetic works like In Praise of the Holy Cross (c. 810) demonstrated innovative Carolingian humanism.[30] As abbot, Hrabanus reformed the community, supervised construction, and prioritized the scriptorium and library, amassing resources to introduce Germans to religious and classical texts, which included over 600 monks by the mid-9th century.[31] The Fulda scriptorium's achievements included copying and preserving key classical manuscripts, such as the Codex Fuldanus (c. 9th century), the oldest surviving witness to Tacitus's Annales and Historiae, and a version of Ammianus Marcellinus's Res Gestae, ensuring their transmission amid the era's textual scarcity.[32] The library eventually held around 2,000 volumes by the High Middle Ages, encompassing ancient authors whose works survived primarily through Fulda's efforts, alongside practical texts like the 9th-century copy of Apicius's De Re Coquinaria, the earliest extant cookbook.[3][33] Successors like Abbot Eigil (822–842, interregnum) contributed hagiographical works, such as the Vita Sancti Sturmi, documenting the abbey's founding under Saint Sturm (d. 779).[3] These endeavors positioned Fulda as a vital node in the Carolingian Renaissance, bridging antique learning with medieval Christianity.Architecture and Physical Site

Early Basilica and Medieval Structures

The abbey church of Fulda, initially constructed as a simple wooden structure shortly after the monastery's founding in 744 by Abbot Sturm, served as the initial basilica housing the tomb of Saint Boniface following his martyrdom and burial there in 754.[3] This early edifice, aligned with Carolingian monastic traditions, emphasized functionality amid the forested Hessian landscape, with stone elements introduced gradually to symbolize permanence and imperial patronage under Charlemagne.[13] Under Abbot Baugulf (780–802), construction began on a more ambitious stone basilica dedicated to the Holy Saviour, incorporating the saint's grave as its focal point; this project was aggressively expanded by his successor, Ratgar (802–817), resulting in a grand three-aisled structure with a transept and distinctive double apses at both east and west ends, emulating Roman basilical models like Old St. Peter's to underscore Fulda's apostolic prestige.[3] [34] The Ratgar Basilica, completed amid internal monastic strife that led to the abbot's deposition, measured approximately 100 meters in length and featured vaulted elements rare for the era, though its opulence strained resources and provoked criticism from figures like Einhard.[35] Abbot Eigil (817–822) moderated the pace, dedicating the church on November 1, 819, in a ceremony attended by regional bishops, while integrating reliquaries and crypt spaces beneath the apses for veneration.[12] Medieval modifications commenced after a devastating fire in 937 razed much of the Carolingian basilica, prompting a Romanesque reconstruction under Abbot Wibert (d. 997) that retained the double-apse layout but added fortified elements reflective of the era's insecurities.[3] Surviving components include the Boniface crypt chapel from the Ratgar era, a low-vaulted chamber directly beneath the high altar preserving the saint's sarcophagus and early relics, which escaped later Baroque overhauls.[36] Concurrently, Abbot Eigil commissioned St. Michael's Church in 822 as a rotunda burial chapel in the monastic cemetery, featuring a central dome and Carolingian proportions; this structure, extended with a west tower and transept arms in the 10th–11th centuries, exemplifies early medieval funerary architecture adapted for communal use.[37] By the 12th century, additional cloister wings and defensive walls encircled these core buildings, forming a fortified ecclesiastical complex amid territorial expansions.[13]Baroque Reconstruction and Later Modifications

The Baroque reconstruction of the abbey church, later known as Fulda Cathedral, commenced in 1704 under Prince-Abbot Adalbert von Schleinitz and was substantially completed by 1712, replacing the dilapidated Carolingian-era basilica. Architect Johann Dientzenhofer, drawing inspiration from Roman Baroque designs including St. Peter's Basilica, planned the new structure in 1700 as a three-aisled basilica incorporating elements of the previous building to preserve the shrine of Saint Boniface. This project marked a significant transformation of the abbey complex into a prominent example of German Baroque architecture, emphasizing grandeur and spatial dynamics typical of the style.[38][39] Dientzenhofer also contributed to contemporaneous expansions, including the redesign of the adjacent Stadtschloss (abbatial palace) between 1707 and 1712, enhancing the residence's Baroque facade and interiors to reflect the prince-abbot's status. Further modifications in the mid-18th century included the construction of new Baroque conventual buildings attached to the cathedral's west side from 1771 to 1778, undertaken during the tenure of Prince-Abbot Heinrich von Bibra, who oversaw the abbey's elevation to a prince-bishopric in 1752, thereby designating the church as a cathedral. These additions solidified Fulda's role as a Baroque residence town, with coordinated architectural elements underscoring the institution's imperial immediacy and cultural prestige.[40] Following the abbey's secularization and dissolution in 1802–1803 amid Napoleonic reforms, the physical site underwent limited structural modifications in the 19th century, primarily consisting of adaptive repurposing and maintenance rather than major redesigns. The cathedral continued in ecclesiastical use under the reestablished Diocese of Fulda, with the former monastic buildings serving secular functions such as administrative offices and residences, preserving much of the Baroque fabric despite the loss of monastic governance. Restoration efforts in the 19th and early 20th centuries focused on conserving Dientzenhofer's designs, ensuring the site's architectural integrity amid shifting political contexts.[36]Decline, Dissolution, and Legacy

Reformation Impacts, Wars, and Secularization (16th-19th Centuries)

The Protestant Reformation posed significant challenges to the Catholic Princely Abbey of Fulda in the 16th century, with early concessions to reformist ideas under Abbot Johannes III von Henneberg (r. 1521–1541), who consented to a decree incorporating Reformation doctrines.[1] However, subsequent leadership, particularly Abbot Balthasar von Dernbach (r. 1570–1606), actively resisted Protestant incursions, enlisting Jesuit support from 1571 to enforce Counter-Reformation measures and restore Catholic orthodoxy by around 1620.[3] [1] These efforts preserved Fulda's Catholic identity amid regional Protestant advances, though internal chapter opposition temporarily banished Dernbach in 1576 until his return in 1602.[1] The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) inflicted severe devastation on Fulda, including widespread looting by Hessian forces that destroyed much of the abbey's renowned library collection accumulated since the Carolingian era.[3] In 1631, Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus granted Fulda as a fief to Landgrave William V of Hesse in an attempt to impose Protestantism, but Catholic forces regained control following the 1634 Battle of Nördlingen, restoring the abbey's autonomy under the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.[1] The conflict ravaged the countryside and abbey structures, prompting post-war reconstruction under later abbots, such as the initiation of Baroque renovations in the late 17th century.[3] Secularization culminated in the early 19th century as part of the broader mediatization of ecclesiastical states. The 1802 Treaty of Paris and the subsequent Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803 dissolved the monastic principality, suppressing the abbey while preserving the diocese; the territory, spanning approximately 40 square miles with 100,000 inhabitants, was initially awarded to the Prince of Orange as a secular holding.[1] [3] In 1809, it passed to Napoleon's Grand Duchy of Frankfurt, then to Hesse-Kassel in 1815, and finally to Prussia in 1866, marking the end of Fulda's independent princely status after nearly a millennium.[1] [41] The university, established in 1734, operated until 1803 alongside these territorial shifts.[41]Enduring Influence and Modern Preservation

Although the Princely Abbey of Fulda was dissolved in 1802 and its territories secularized the following year, its spiritual influence persists through the Diocese of Fulda, which evolved from the prince-bishopric and continues as the Catholic ecclesiastical authority in the region.[42] The Fulda Cathedral, originally the abbey church dedicated to Christ the Saviour, serves as the diocesan seat and preserves the relics of Saint Boniface, drawing pilgrims and underscoring the site's ongoing religious significance.[36] The abbey's cultural legacy includes the preservation of classical texts through its medieval scriptorium, with many manuscripts now safeguarded in institutions that trace their origins to Fulda's scholarly tradition.[43] Modern preservation initiatives emphasize restoring key architectural elements tied to the abbey. The cathedral sustained wartime damage during World War II but was fully restored by 1954.[44] Between 1992 and 1996, extensive work recreated original interior colors and features, enhancing the Baroque structure's authenticity.[38] The Diocese of Fulda oversees ongoing monument care, as detailed in its annual reports on ecclesiastical heritage, covering sites like the former Benedictine structures in the city center.[45] In 2006, the restoration of Ottonian wall-paintings in the crypt of St. Andreas, linked to the abbey's early monastic complex, earned recognition from the European Heritage Awards for exemplary conservation of medieval church interiors.[46] These efforts ensure the physical legacy of Fulda's princely era remains accessible, supporting tourism and historical study in Hesse.Leadership Chronology

Abbots of Fulda

The abbots of Fulda directed the Benedictine monastery from its foundation in 744 until the transition to prince-abbots around 1221, overseeing spiritual, intellectual, and territorial growth amid Carolingian and Ottonian influences. Sturm, the inaugural abbot (744–779), established the community following Boniface's directive, drawing on Benedictine traditions observed at Monte Cassino. Baugulf (779–802) prioritized scholarly pursuits and estate management, fostering the scriptorium's development. Ratgar (802–817) initiated ambitious basilica construction but encountered monastic dissent, resulting in his removal by Louis the Pious. Eigil (818–822) provided brief stability before Rabanus Maurus (822–842), a prolific theologian and teacher, amplified Fulda's reputation as a Carolingian learning center.[13][9][47][3] Later abbots navigated feudal expansions, imperial privileges granted in 765, and internal reforms, with the Catalogus abbatum Fuldensium documenting successions up to the 10th century. Egbert (1047–1058) exemplified medieval leadership through administrative seals preserving abbatial authority. The complete roster, derived from monastic annals and charters, is as follows:[48]| Name | Reign |

|---|---|

| Sturmius | 744–779 |

| Baugulf | 779–802 |

| Ratgar | 802–817 |

| Eigil | 818–822 |

| Rabanus Maurus | 822–842 |

| Hatto I | 842–856 |

| Thioto | 856–869 |

| Sigihart | 869–891 |

| Huoggi | 891–915 |

| Helmfried | 915–916 |

| Haicho | 917–923 |

| Hiltibert | 923–927 |

| Hadamar | 927–956 |

| Hatto II | 956–968 |

| Werinheri | 968–982 |

| Branthoh I | 982–991 |

| Hatto III | 991–997 |

| Erkanbald | 997–1011 |

| Branthoh II | 1011–1013 |

| Poppo | 1013–1018 |

| Richard | 1018–1039 |

| Sigiwart | 1039–1043 |

| Rohing | 1043–1047 |

| Egbert | 1047–1058 |

| Sigfried von Eppenstein | 1058–1060 |

| Widerad von Eppenstein | 1060–1075 |

| Ruothart | 1075–1096 |

| Godefrid | 1096–1109 |

| Wolfhelm | 1109–1114 |

| Erlolf von Bergholz | 1114–1122 |

| Ulrich von Kemnaten | 1122–1126 |

| Heinrich I. von Kemnaten | 1126–1132 |

| Bertho I. von Schlitz | 1132–1134 |

| Konrad I | 1134–1140 |

| Aleholf | 1140–1148 |

| Rugger I | 1148–? |

| Heinrich II. von Bingarten | 1148–1149 |

| Markward I | 1150–1165 |

| Gernot | 1165–? |

| Hermann | 1165–1168 |

| Burchard Graf von Nürings | 1168–1176 |

| Rugger II | 1176–1177 |

| Konrad II | 1177–1192 |

| Heinrich III. von Kronberg | 1192–1216 |

| Hartmann I | 1216–1217 |

| Kuno | 1217–1221 |