Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Locus (genetics)

View on Wikipedia

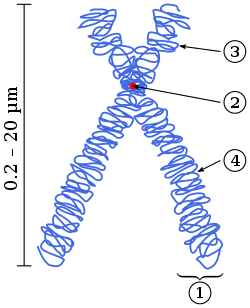

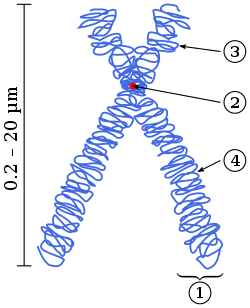

(1) Chromatid

(2) Centromere

(3) Short (p) arm

(4) Long (q) arm

In genetics, a locus (pl.: loci) is a specific, fixed position on a chromosome where a particular gene or genetic marker is located.[1] Each chromosome carries many genes, with each gene occupying a different position or locus; in humans, the total number of protein-coding genes in a complete haploid set of 23 chromosomes is estimated at 19,000–20,000.[2]

Genes may possess multiple variants known as alleles, and an allele may also be said to reside at a particular locus. Diploid and polyploid cells whose chromosomes have the same allele at a given locus are called homozygous with respect to that locus, while those that have different alleles at a given locus are called heterozygous.[3] The ordered list of loci known for a particular genome is called a gene map. Gene mapping is the process of determining the specific locus or loci responsible for producing a particular phenotype or biological trait. Association mapping, also known as "linkage disequilibrium mapping", is a method of mapping quantitative trait loci (QTLs) that takes advantage of historic linkage disequilibrium to link phenotypes (observable characteristics) to genotypes (the genetic constitution of organisms), uncovering genetic associations.

Nomenclature

[edit]

The shorter arm of a chromosome is termed the p arm or p-arm, while the longer arm is the q arm or q-arm. The chromosomal locus of a typical gene, for example, might be written 3p22.1, where:[citation needed]

- 3 = chromosome 3

- p = p-arm

- 22 = region 2, band 2 (read as "two, two", not "twenty-two")

- 1 = sub-band 1

Thus the entire locus of the example above would be read as "three P two two point one". The cytogenetic bands are areas of the chromosome either rich in actively-transcribed DNA (euchromatin) or packaged DNA (heterochromatin). They appear differently upon staining (for example, euchromatin appears white and heterochromatin appears black on Giemsa staining). They are counted from the centromere out toward the telomeres.[citation needed]

| Component | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 3 | The chromosome number |

| p | The position is on the chromosome's short arm (a common apocryphal explanation is that the p stands for petit in French); q indicates the long arm (chosen as next letter in alphabet after p; it is also said that q stands for queue, meaning "tail" in French[4]). |

| 22.1 | The numbers that follow the letter represent the position on the arm: region 2, band 2, sub-band 1. The bands are visible under a microscope when the chromosome is suitably stained. Each of the bands are numbered, beginning with 1 for the band nearest the centromere. Sub-bands and sub-sub-bands are visible at higher resolution.[citation needed] |

A range of loci is specified in a similar way. For example, the locus of gene OCA1 may be written "11q1.4-q2.1", meaning it is on the long arm of chromosome 11, somewhere in the range from sub-band 4 of region 1 to sub-band 1 of region 2.[citation needed]

The ends of a chromosome are labeled "pter" and "qter", and so "2qter" refers to the terminus of the long arm of chromosome 2.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wood, E.J. (1995). "The encyclopedia of molecular biology". Biochemical Education. 23 (2): 1165. doi:10.1016/0307-4412(95)90659-2.

- ^ Ezkurdia, Iakes; Juan, David; Rodriguez, Jose Manuel; Frankish, Adam; Diekhans, Mark; Harrow, Jennifer; Vazquez, Jesus; Valencia, Alfonso; Tress, Michael L. (2014-11-15). "Multiple evidence strands suggest that there may be as few as 19,000 human protein-coding genes". Human Molecular Genetics. 23 (22): 5866–5878. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu309. ISSN 1460-2083. PMC 4204768. PMID 24939910.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Genetics". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ^ "NCBI Genetics Review". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 9 May 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- Michael, R. Cummings. (2011). Human Heredity. Belmont, California: Brooks/Cole.