Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

James Cartwright

View on Wikipedia

James Edward "Hoss" Cartwright[2] (born September 22, 1949) is a retired United States Marine Corps general who last served as the eighth vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from August 31, 2007, to August 3, 2011. He previously served as the Commander, U.S. Strategic Command, from September 1, 2004, to August 10, 2007, and as Acting Commander, U.S. Strategic Command from July 9, 2004, to September 1, 2004. He retired from the Marine Corps on August 3, 2011, after nearly 40 years of service.

Key Information

Cartwright was accused of providing classified information that was published in the book Confront and Conceal by David Sanger.[3] During the course of the investigation, Cartwright agreed to be interviewed by the FBI without a lawyer present.[4] He was indicted for lying to the FBI regarding the time and locations of meetings with Sanger.[4] Cartwright was never charged with leaking any classified information; Sanger maintains that Cartwright did not provide him with any classified material.[4] On October 17, 2016, he pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI regarding an investigation into the source of leaked classified information. He had been scheduled to be sentenced on January 31, 2017,[5] but was pardoned and had his security clearance restored[4] by President Barack Obama on January 17, 2017.[6]

Early life and education

[edit]Cartwright was born on September 22, 1949, in Rockford, Illinois, and attended West High School before going on to the University of Iowa. While there he was a scholarship swimmer for the Iowa Hawkeyes.[1]

Career

[edit]

Cartwright was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps in November 1971. He attended Naval Flight Officer training and graduated in April 1973. He attended Naval Aviator training and graduated in January 1977. He has operational assignments as a Naval Flight Officer in the F-4, and as a pilot in the F-4, OA-4, and F/A-18.[7] His callsign comes from the fictional character Eric "Hoss" Cartwright, the middle brother on the classic 1960s TV show Bonanza, who was played by actor Dan Blocker.

Cartwright's operational assignments include: Commanding General, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing (2000–2002); Deputy Commanding General Marine Forces Atlantic (1999–2000); Commander Marine Aircraft Group 31 (1994–1996); Commander Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 232 (1992); Fixed Wing Operations Marine Aircraft Group 24 (1991); Commander Marine Aviation Logistics Squadron 12 (1989–1990); Administration Officer and Officer-In-Charge Deployed Carrier Operations VMFAT-101 (1983–1985); Aircraft Maintenance Officer VMFA-235 (1979–1982); Line Division Officer VMFA-333 USS Nimitz (1975–1977); Embarkation OIC VMFA-251 & 232 (1973–1975).[7]

Cartwright's staff assignments include: Director for Force Structure, Resources and Assessment, J-8 the Joint Staff (2002–2004); Directorate for Force Structure, Resources and Assessment, J-8 the Joint Staff (1996–1999); Deputy Aviation Plans, Policy, and Budgets Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps (1993–1994); Assistant Program Manager for Engineering, F/A-18 Naval Air Systems Command (1986–1989).[7]

Cartwright was named the Outstanding Carrier Aviator by the Association of Naval Aviation in 1983. He graduated with distinction from the Air Command and Staff College, Maxwell AFB 1986, and received his Master of Arts in National Security and Strategic Studies from the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, 1991. In 2008, he was honored with the Naval War College Distinguished Graduate Leadership Award. He was selected for and completed a fellowship with MIT Seminar XXI in 1994.[8]

From July 9, 2004, to September 1, 2004, Lieutenant General Cartwight served as Acting Commander, United States Strategic Command while awaiting official assumption of office and promotion as Strategic Command's new commander. On September 1, 2004, Cartwright was sworn in as Commander, United States Strategic Command.[9] He was promoted to full general on the same day.[10]

On June 8, 2007, Defense Secretary Robert Gates recommended Cartwright to be the next Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to replace retiring Admiral Edmund Giambastiani. President George W. Bush formally announced the nomination, with that of Admiral Michael Mullen to be Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on June 28, 2007.[11]

Senator John Warner of Virginia, the senior Republican on the Senate Armed Services Committee, stated, "General Cartwright has an extraordinary grasp and understanding of the global posture that America must maintain in this era of new and ever-changing threats".[12]

Cartwright's nomination was confirmed by the full Senate on August 3, 2007. Due to the retirement of Admiral Giambastiani on July 27, 2007, Cartwright assumed the position immediately upon confirmation.[13] He was sworn in on August 31, 2007, as the 8th Vice Chairman.[14] On March 18, 2009, Secretary of Defense Gates announced that Cartwright had been nominated for a second term as Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.[15] He was confirmed by the Senate on July 31, 2009.[16]

The military investigated Cartwright in 2009 and 2010 for possible misconduct involving a female Marine captain, and investigators recommended administrative action for "failure to discipline a subordinate" and "fostering an unduly familiar relationship". Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, however, reviewed the evidence and found it insufficient to warrant corrective action for even the lesser offenses. He stated, "I do not agree with the conclusion that General Cartwright maintained an 'unduly familiar relationship' with his aide. Nor do I agree that General Cartwright's execution of his leadership responsibilities vis-à-vis his aide or any other member of his staff was inconsistent with the leadership requirements".[17] Questions about how he oversaw his staff, however, were mentioned as a reason Cartwright had fallen out as the favored candidate of President Obama for Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 2011. Army chief Gen. Martin Dempsey was named to the post. "Some Republicans [had] ... quietly criticized Gen. Cartwright, calling him 'Obama's general,'" one report at the time also said.[18]

Cartwright held his retirement ceremony on August 3, 2011. During the ceremony, Deputy Secretary of Defense William J. Lynn III presented Cartwright his fourth Defense Distinguished Service Medal. He also received the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard distinguished service medals.[19]

Dates of rank

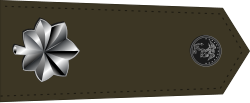

[edit]| Insignia | Rank | Date |

|---|---|---|

|

Second Lieutenant | November 12, 1971 |

|

First Lieutenant | November 1, 1973 |

|

Captain | November 7, 1976 |

|

Major | August 1, 1977 |

|

Lieutenant Colonel | November 1, 1981 |

|

Colonel | March 9, 1993 |

|

Brigadier General | October 1, 1997 |

|

Major General | 2001 |

|

Lieutenant General | May 6, 2002 |

|

General | July 21, 2004 |

Military awards and badges

[edit]Cartwright received the following decorations, awards, and badges:

| |||

| |||

Leak investigation, conviction, and pardon

[edit]In June 2013, it was reported that Cartwright had received a target letter from the U.S. Justice Department, informing him that he was under investigation for leaking classified information about Stuxnet, a computer virus used in a U.S.-Israel cyberattack against centrifuges in Iranian nuclear facilities (see Operation Olympic Games).[21] Federal investigators reportedly suspected that Cartwright leaked details of the operation to a New York Times reporter.[22]

In March 2015, the Washington Post reported that the sensitive leak investigation, led by Rod Rosenstein, had "stalled amid concerns that a prosecution in federal court could force the government to confirm" information about the highly classified program.[22] U.S. officials feared that if classified information were revealed in any information, it would harm U.S.-Israeli relations and would also complicate the then-pending negotiations on an agreement with Iran over the nuclear program.[22] It was reported that federal prosecutors had discussions with the Office of White House Counsel, then led by Kathryn Ruemmler, on whether certain material important to the case would be declassified, and Ruemmler conveyed that the government was unwilling to provide the documentation.[22]

Cartwright denied any wrongdoing; his attorney, Gregory B. Craig, said in March 2015 that Cartwright had no contact with federal investigators for over a year.[22] Craig stated: "General Cartwright has done nothing wrong. He has devoted his entire life to defending the United States. He would never do anything to weaken our national defense or undermine our national security. Hoss Cartwright is a national treasure, a genuine hero and a great patriot."[22]

On November 2, 2012, in an interview with the FBI, Cartwright denied he was the source of the leaks. On October 17, 2016, Cartwright entered a guilty plea in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on a charge of making false statements during the leak investigation, a felony.[23]

Outgoing President Barack Obama pardoned Cartwright on January 17, 2017,[24] two weeks prior to his scheduled sentencing hearing.[6]

Post-retirement work

[edit]Cartwright was the inaugural holder of the Harold Brown Chair in Defense Policy Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a think tank – a post he held from 2011 until 2017.[25] In addition, Cartwright serves as a member of the board of directors of The Raytheon Company,[26] a senior fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard Kennedy School,[27] and as a defense consultant for ABC News.[28]

Cartwright is an advisor for several corporate entities involved in global management consulting, technology services and program solutions, predictive and big data analytics, and advanced systems engineering, integration, and decision-support services.[citation needed][buzzword] He serves as an advisor to the board of directors for Accenture,[citation needed] Enlightenment Capital,[citation needed] IxReveal,[citation needed] Logos Technologies,[citation needed] Opera Solutions,[citation needed] and TASC Inc.[citation needed] He is also affiliated with a number of professional organizations, including the Aspen Strategy Group,[citation needed] The Atlantic Council,[29] the Nuclear Threat Initiative,[citation needed] and the Sanya Initiative.[citation needed]

Cartwright is also a leading advocate for the phased and verified elimination of all nuclear weapons worldwide[30] ("Global Zero (campaign)"). In October 2011, he spoke at the Global Zero Summit at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California,[31] and currently serves as Chair of the Global Zero U.S. Nuclear Policy Commission, which in May 2012 released its report, "Modernizing U.S. Nuclear Force Structure and Policy," calling for the United States and Russia to reduce their nuclear arsenals 80% to 900 total weapons each, which would pave the way to bringing other nuclear weapons countries into the first-in-history multilateral nuclear arms negotiations.[32]

In June 2015, Cartwright was a signatory to a public letter written by a bipartisan group of 19 U.S. diplomats, experts, and others, on the then-pending negotiations for an agreement between Iran and world powers over Iran's nuclear program.[33][34] That letter outlined concerns about several provisions in the then-unfinished agreement and called for a number of improvements to strengthen the prospective agreement and win the letter-writers' support for it.[33] The final agreement, concluded in July 2015, shows the influence of the letter.[33] Cartwright endorsed the final agreement in August 2015, becoming one of 36 retired generals and admirals to sign an open letter in support of the agreement.[35][full citation needed]

- Government civilian positions

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Bush, President George W. (June 28, 2007). "President Bush Nominates Admiral Michael Mullen and General James Cartwright to Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff". Office of the Press Secretary, The White House. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ^ "Pardons Granted by President Barack Obama (2009-2014) | PARDON | Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (January 17, 2017). "Obama Pardons James Cartwright, General Who Lied to F.B.I. in Leak Case". The New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Sanger, David E. The perfect weapon : war, sabotage, and fear in the cyber age (First ed.). New York. ISBN 9780451497895. OCLC 1039082430.

- ^ Gerstein, Josh (January 10, 2017). "Journalists' letters submitted in Cartwright leniency bid". Politico. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Williams, Katie Bo (January 17, 2017). "Obama pardons James Cartwright in leak case". The Hill. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Official Biography: General James E. Cartwright, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff". U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved May 16, 2006.

- ^ Art, Robert (September 1, 2015). "From the Director: September, 2015". MIT Seminar XXI. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.; Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "Find Alumni". MIT Seminar XXI. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ "General James E. Cartwright, Commander, U.S. Strategic Command". United States Marine Corps. August 30, 2004. Archived from the original (Official Biography) on June 14, 2006. Retrieved May 16, 2006.

- ^ "Public Directory of: U.S. Marine Corps General Officers & Senior Executives", U.S. Marine Corps, January 8, 2008.

- ^ McMichael, William H. (June 8, 2007). "Gates taps new JCS chairman, vice chair". Marine Corps Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2007.

- ^ Starr, Barbara and Suzanne Malveaux (June 8, 2007). "Pace leaving as Joint Chiefs chairman". CNN. Retrieved June 9, 2007.

- ^ Miles, Donna (August 6, 2007). "Senate Confirms Mullen, Cartwright for Top Military Positions". DefenseLINK. U.S. Department of Defense. American Forces Press Service. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (August 31, 2007). "Gates Swears in Cartwright as Vice Chairman". DefenseLINK. U.S. Department of Defense. American Forces Press Service. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ^ Tan, Michelle (March 18, 2009). "Mullen, Cartwright nominated for 2nd terms". Marine Corps Times. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ U.S. Senate Legislation & Records Home Nominations Confirmed (Non-Civilian)

- ^ Shanker, Thom (February 23, 2011). "General James Cartwright Is Cleared of Sex Accusations". The New York Times.

- ^ Entous, Adam, "Top Officer in Army to Lead Joint Chiefs", The Wall Street Journal, May 31, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ "Panetta Honors Cartwright During Farewell Tribute" Archived 2015-04-14 at the Wayback Machine American Forces Press Service, Aug. 3, 2011, Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ The Chairmanship of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1949-2012 (PDF) (2 ed.). Joint History Office. October 27, 2012. p. 320. ISBN 978-1480200203.

- ^ Isikoff, Michael (June 27, 2013). "Ex-Pentagon general target of leak investigation, sources say". NBC News. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Ellen Nakashima & Adam Goldman, Leak investigation stalls amid fears of confirming U.S.-Israel operation, Washington Post (March 10, 2015).

- ^ "Former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Pleads Guilty to Federal Felony in Leak Investigation". justice.gov. United States Government. October 17, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Peter Maas (January 18, 2017). "Obama's Pardon of Gen. James Cartwright Is a New Twist in the War on Leaks". theintercept.com. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ "Harold Brown Chair | Center for Strategic and International Studies".

- ^ "James E. Cartwright Elected to Raytheon Board of Directors". Raytheon. January 27, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Smith, James (October 2, 2012). "Former Joint Chiefs Vice Chairman James Cartwright Appointed Senior Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School's Belfer Center". Harvard Kennedy School. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Ford, David (May 21, 2012). "General Cartwright (USMC ret.) and General Chiarelli (USA ret.) Join ABC News". ABC News. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ "Board of Directors". Atlantic Council. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- ^ Shanker, Thom (May 15, 2012). "Former Commander of U.S. Nuclear Forces Calls for Large Cut in Warheads". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Willer-Allred, Michele (October 11, 2011). "Global Zero Summit pushes to reduce nuclear weapons". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ "Towards a More Disarmed World". FT.com. The Financial Times. May 15, 2012. Archived from the original on December 11, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c William J. Broad, Iran Accord's Complexity Shows Impact of Bipartisan Letter, The New York Times (14 July 2015).

- ^ Public Statement on U.S. Policy Toward the Iran Nuclear Negotiations Endorsed by a Bipartisan Group of American Diplomats, Legislators, Policymakers, and Experts, Washington Institute for Near East Policy (24 June 2015).

- ^ [Read: An open letter from retired generals and admirals on the Iran nuclear deal], Washington Post (August 2015).[full citation needed]

- ^ "DOD Announces New Defense Policy Board Members". U.S. Department of Defense. October 4, 2011. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Review of 2014 QDR

External links

[edit]- Joint Chiefs of Staff

- U.S. Strategic Command

- Involvement with "Olympic Games" aka Stuxnet

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- James E Cartwright on Facebook

James Cartwright

View on GrokipediaJames Edward Cartwright (born September 22, 1949) is a retired four-star general of the United States Marine Corps who served as the eighth Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from August 2007 to July 2011, the second-highest uniformed position in the U.S. military.[1] A career naval aviator qualified in the F-4 Phantom, OA-4 Skyhawk, and F/A-18 Hornet, he commanded U.S. Strategic Command from 2004 to 2007, overseeing nuclear deterrence, missile defense, and global strike capabilities.[2][3] Earlier in his 40-year service, Cartwright held key aviation and logistics commands, earning recognition as the Outstanding Carrier Aviator of the Year in 1983 by the Association of Naval Aviation.[3] Post-retirement, he joined advisory boards including the Center for Strategic and International Studies, while in 2016 pleading guilty to federal charges of making false statements in connection with leaking classified information about a cyber operation against Iran, resulting in a reduced sentence and later pardon.[4][3] His tenure emphasized strategic modernization, including debates on nuclear triad sustainability amid fiscal constraints.[3]

Early life and education

Upbringing and family influences

James Edward Cartwright was born on September 22, 1949, in Rockford, Illinois, the eldest of six children and the only son in a working-class family.[5][3] Growing up in this Midwestern industrial city during the post-World War II economic expansion, Cartwright experienced a household environment that prioritized diligence amid modest means, with no documented familial military heritage but a setting conducive to personal responsibility as the sole male sibling.[1] From childhood, he contributed labor on his grandparents' farm in Rockford, often residing there during summers to tend crops and livestock, an experience that instilled early lessons in self-reliance, physical endurance, and practical problem-solving central to Midwestern agrarian values.[6] These formative activities, rather than formal organizations, shaped his initial inclinations toward disciplined effort and community-oriented service, reflecting the resilience fostered in working-class families navigating the era's transition from wartime austerity to peacetime industry.[5]Academic pursuits and commissioning

Cartwright attended the University of Iowa on a swimming scholarship, competing as a member of the Iowa Hawkeyes swim team during the late 1960s.[7] His participation in competitive swimming emphasized physical endurance, rigorous training regimens, and collaborative teamwork, qualities that later supported the demands of naval aviation.[6] He graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1971.[3] Following graduation, Cartwright was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps in November 1971. This entry into officer service marked his transition from academic and athletic pursuits to military professionalism, leveraging his quantitative and scientific inclinations—initially oriented toward pre-medical studies—for problem-solving in operational contexts.[6] Cartwright then entered Naval Flight Officer training, completing the program in April 1973 and qualifying for service in multi-crew aircraft roles. This foundational phase built on his undergraduate discipline, adapting athletic resilience to the precision and high-stakes environment of military aviation, where analytical skills were essential for navigation and mission execution.[8]Military career

Initial service and aviation assignments

Cartwright was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps in November 1971 upon graduation from the University of Iowa.[9] He subsequently entered Naval Flight Officer training, graduating in April 1973, before completing Naval Aviator training and earning his aviator wings in January 1977.[10] His early operational assignments involved serving as a naval flight officer in the F-4 Phantom II, focusing on fighter roles amid Cold War-era demands for readiness.[3] Transitioning to pilot duties, he flew the F-4 Phantom II, OA-4 Skyhawk in reconnaissance and forward air control capacities, and F/A-18 Hornet in fighter-attack missions across Marine Corps aviation units during the 1970s and 1980s, building expertise in tactical aviation under high-risk conditions.[11] This foundational experience culminated in his selection as the Navy's Outstanding Carrier Aviator of the Year in 1983, affirming his proficiency in carrier-based operations.[12]Operational commands and deployments

Cartwright commanded Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 232 (VMFA-232), leading F/A-18 Hornet operations in tactical aviation roles during the late Cold War and early post-Cold War periods.[10] As commander of Marine Aircraft Group 31 from 1994 to 1996, he oversaw multiple fixed-wing and rotary-wing squadrons at Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort, South Carolina, managing training, maintenance, and deployment readiness for expeditionary aviation forces.[10] [13] In 1999, Cartwright served as Deputy Commanding General of Marine Forces Atlantic, coordinating joint and combined exercises to enhance amphibious and aviation integration across Atlantic theater operations.[9] He then assumed command of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing from 2000 to 2002, headquartered at Marine Corps Base Camp S. D. Butler, Okinawa, Japan, where he directed aviation combat elements supporting III Marine Expeditionary Force missions, emphasizing logistics sustainment and rapid response capabilities amid shifting regional security dynamics following the Cold War.[9] [13] Under his leadership, the wing maintained operational tempo through forward-deployed squadrons, contributing to deterrence postures in the Asia-Pacific without direct combat engagements during this tenure.[9]Strategic leadership roles

Cartwright was appointed Commander of the United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) on September 1, 2004, simultaneously receiving promotion to the rank of four-star general.[10] In this role, he directed a unified command overseeing strategic deterrence missions, encompassing nuclear operations, space-based assets, and conventional global strike forces, with responsibilities extending to information operations and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance integration.[14] Under his leadership, USSTRATCOM consolidated these functions following the 2002 reorganization, emphasizing empirical assessments of capability overlaps to streamline operations and mitigate redundancies in command structures.[15] A key initiative involved reorganizing nuclear and global strike elements to address identified vulnerabilities in response timelines and interoperability. Cartwright prioritized data-derived reforms to command-and-control (C2) systems, including the deployment of advanced collaboration platforms that enhanced real-time information sharing across domains.[16] These changes yielded quantifiable improvements, such as reduced decision latencies in simulated scenarios, by establishing causal connections between legacy system silos and diminished deterrence credibility against peer adversaries.[17] During real-world contingencies, including North Korea's series of missile tests on July 5, 2006, Cartwright's command activated integrated missile defense and global strike monitoring protocols, confirming the efficacy of post-reorganization enhancements in tracking and potential interception.[17] This response highlighted how targeted investments in C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) infrastructure had fortified USSTRATCOM's ability to counter proliferation threats through verifiable operational readiness.[18]Tenure as Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

Marine Corps Gen. James E. Cartwright was sworn in as the eighth Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff on August 31, 2007, marking the first time a Marine held the position.[19] In this capacity, he acted as the principal assistant to Chairman Adm. Michael G. Mullen, managing Joint Staff operations, resource allocation, and interservice coordination while advising the Secretary of Defense and President on global military matters across two administrations.[3] His tenure coincided with sustained combat operations, emphasizing joint force effectiveness and adaptation to asymmetric threats.[9] Cartwright contributed to strategic guidance on the Iraq and Afghanistan theaters, including the 2007-2008 Iraq surge's consolidation and the 2009-2010 Afghanistan troop increase under President Obama.[20] He testified alongside Secretary Gates on progress in Iraq, highlighting emerging stability and Iraqi security force capabilities amid planned drawdowns.[21] In Afghanistan, he supported comprehensive surge strategies integrating military, civilian, and metrics for evaluating counterinsurgency outcomes, such as expanded provincial reconstruction teams from 320 to over 1,100 personnel by late 2010.[22] As overseer of long-term defense planning, Cartwright advanced modernization initiatives to enhance joint interoperability, including integration of the F-35 Lightning II across Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps platforms for multi-role strike capabilities.[23] The program aimed to replace aging fleets with a common airframe reducing logistics costs and improving networked warfare, though it encountered delays and cost growth exceeding initial projections, prompting scrutiny from fiscal analysts.[24] Cartwright retired on August 3, 2011, concluding his four-year term after President Obama selected Army Gen. Martin E. Dempsey as Chairman over him, reportedly due to internal critiques of his views on operational priorities like Libya intervention rather than unified support for emerging budget constraints.[25] [26] Some observers interpreted the decision as signaling resistance to proposed efficiency reforms amid fiscal pressures, though Cartwright emphasized institutional continuity in his farewell.[9]Strategic doctrines and policy advocacy

Nuclear weapons policy and deterrence debates

As Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 2007 to 2011, Cartwright endorsed the New START treaty signed in April 2010, which capped U.S. and Russian deployed strategic nuclear warheads at 1,550 and delivery vehicles at 700, emphasizing verifiable reductions to enhance strategic stability amid post-Cold War realities.[27] He argued that the treaty addressed outdated mutual assured destruction doctrines ill-suited for 21st-century threats, allowing resource reallocation while maintaining deterrence through transparency and inspections.[27] Post-retirement, Cartwright advocated further cuts beyond New START limits, chairing a 2012 Global Zero panel that recommended reducing the total U.S. arsenal to 900 warheads (450 deployed) by relying on advanced simulations demonstrating redundancy in retaliatory capabilities—claiming 300 weapons could inflict catastrophic damage sufficient for deterrence against major powers.[28] [29] He contended these reductions would yield $100-120 billion in savings over a decade by eliminating land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and excess bombers, redirecting funds to conventional forces and nonproliferation, while stockpile stewardship programs—advanced under his earlier command of U.S. Strategic Command (2004-2007)—ensured warhead reliability without underground testing via computational modeling and subcritical experiments that certified the arsenal's 90-95% confidence levels since the 1992 testing moratorium.[30] [31] Critics, including deterrence specialists, countered that such proposals underestimated multi-adversary dynamics, where U.S. superiority counters simultaneous threats from Russia (expanding tactical nuclear deployments to over 1,500 by 2015) and China (modernizing to 350+ warheads with hypersonic capabilities by 2020), potentially eroding escalation dominance and inviting riskier conventional conflicts.[32] They argued Cartwright's simulation-based redundancy claims overlooked real-world variables like damage expectancy against hardened targets and adversary countermeasures, prioritizing arms control optics over empirical evidence of peer competitors' non-compliance—such as Russia's 2014 INF Treaty violations—thus weakening the triad's flexibility in extended deterrence scenarios for allies like NATO members facing regional nuclear coercion.[32] [33] These debates highlighted tensions between cost-driven minimalism and hard-power realism, with stewardship data supporting maintenance of existing stockpiles but not justifying unilateral cuts absent reciprocal verifiable reductions; U.S. arsenal levels stabilized around 3,800 total warheads by 2015, reflecting hawkish resistance to further drawdowns amid rising global tensions.[34]Cyber operations and technological innovation

As Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 2007 to 2011, Cartwright played a pivotal role in advocating for the formal recognition of cyberspace as a warfighting domain, influencing the establishment of U.S. Cyber Command on May 21, 2010, under U.S. Strategic Command's oversight during his earlier tenure as its commander from 2004 to 2007.[35][36] He viewed cyber operations as a critical force multiplier, enabling effects between diplomatic sanctions and kinetic strikes, with integrated exercises like Cyber Flag—initiated in 2008—demonstrating practical efficacy in simulating offensive and defensive maneuvers across networks.[36][37] Cartwright emphasized offensive cyber capabilities to deter adversaries, arguing that revealing such tools could enhance strategic restraint without immediate escalation to physical conflict, thereby reducing reliance on ground forces in certain scenarios.[38][39] However, he cautioned that cyber employment required deliberate pre-use analysis due to inherent uncertainties, including persistent challenges in attributing attacks amid state-sponsored proxies and the risk of unintended proliferation or retaliatory spirals, as evidenced by post-2010 incidents where cyber tools escaped control and complicated international responses.[40] To accelerate technological adaptation, Cartwright promoted partnerships between the Department of Defense and private industry through initiatives like the Global Innovation and Strategy Center established under his Strategic Command leadership in 2006, which facilitated faster integration of commercial technologies into military systems and contributed to streamlined procurement processes by leveraging external expertise over traditional bureaucratic timelines.[12] This approach yielded measurable gains in areas such as network defense tools, though empirical outcomes remained constrained by the domain's volatility and the need for verifiable causal links between cyber actions and battlefield effects.[41]Perspectives on emerging threats and military reform

Cartwright consistently highlighted the evolving threats posed by peer competitors, particularly China and Russia, emphasizing their potential for hybrid warfare combining conventional, cyber, and informational elements. In testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission on April 26, 2016, he addressed strategic competition with China, underscoring the need for the U.S. to counter Beijing's military modernization and asymmetric capabilities in areas like cyberspace and space.[42] Similarly, during a 2014 House Intelligence Committee hearing on nation-state conflicts, Cartwright warned of risks from China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran, advocating preparedness for integrated threats that exploit U.S. vulnerabilities beyond traditional battlefields.[43] He critiqued overreliance on alliance structures, arguing in broader strategic discussions that excessive dependencies could erode U.S. operational autonomy against agile adversaries employing hybrid tactics.[44] To address these challenges, Cartwright pushed for military reforms centered on service integration and innovative doctrines, including asymmetric responses tailored to hybrid threats. As Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs from 2007 to 2011, he contributed to efforts like the Joint Defense Capabilities Study, which recommended enhanced joint planning and exercises to improve interoperability across services, citing examples such as fiscal control over joint training to streamline operations.[45] These initiatives achieved measurable gains in coordinated exercises, yet faced criticism for potentially diverting resources from maintaining U.S. conventional superiority, which Cartwright himself acknowledged as a deterrent factor in adversaries' calculations during a 2006 interview as STRATCOM commander.[14] In advocating software-defined warfare, Cartwright emphasized leveraging digital technologies for agility against bureaucratic inertia. His role as a commissioner on the Atlantic Council's 2025 Commission on Software-Defined Warfare advanced recommendations for integrating software-centric systems to enable rapid adaptation, projecting efficiency improvements in procurement and deployment cycles by reducing hardware dependencies and enabling scalable responses to peer threats like China's cyber advancements.[46] The commission's final report, released March 27, 2025, outlined pathways for near-term readiness, balancing joint exercise achievements with the imperative to prioritize conventional edges amid rising hybrid risks from Russia and China.[46]Honors, ranks, and professional recognition

Dates of promotion and rank progression

James E. Cartwright was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps in November 1971, following completion of the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps program at the University of Iowa.[10] This entry-level rank marked the start of a 40-year career emphasizing aviation leadership and operational expertise within the Marine Corps' focus on expeditionary capabilities and integrated air-ground operations.[3] Cartwright's subsequent advancements reflected sustained merit through command evaluations and assignments in fighter aviation, logistics, and strategic planning roles, progressing from squadron-level leadership in the late 1980s and early 1990s—typically requiring lieutenant colonel rank—to group command by 1994, indicative of colonel status.[10] By the late 1990s, he held deputy commanding general positions, aligning with brigadier general responsibilities, and advanced to major general for wing command from 2000 to 2002.[10] As a lieutenant general, Cartwright directed force structure and resources on the Joint Staff from 2002 to 2004, prior to nomination for U.S. Strategic Command.[10] He attained four-star general rank on September 1, 2004, coinciding with his swearing-in as Commander, U.S. Strategic Command, capping a trajectory built on empirical performance metrics over three decades of service.[6][10] He retired from active duty on September 1, 2011.[3]| Rank | Approximate Period or Date |

|---|---|

| Second Lieutenant | November 1971[10] |

| Lieutenant Colonel (inferred from squadron commands) | Late 1980s–early 1990s[10] |

| Colonel (inferred from group command) | Mid-1990s[10] |

| Brigadier General (inferred from deputy command) | Late 1990s[10] |

| Major General | 2000–2002[10] |

| Lieutenant General | Pre-2004[47] |

| General | September 1, 2004[6] |

Military awards and commendations

Cartwright earned the Naval Aviator Badge upon graduating from Naval Aviator training in January 1977, qualifying him to fly aircraft such as the F-4 Phantom, OA-4 Skyhawk, and F/A-18 Hornet during operational assignments that emphasized aviation leadership and carrier-based expertise.[48][11] This badge underscores his foundational contributions to Marine Corps air operations, including command of Marine Aviation Logistics Squadron 12 and recognition as Outstanding Carrier Aviator of the Year in 1983 by the Association of Naval Aviation.[11] His decorations include two Legion of Merit awards (with one gold star), recognizing exceptionally meritorious conduct in outstanding service, particularly in aviation and joint command roles that involved reorganizing strategic assets like those under U.S. Strategic Command.[49] These awards highlight verifiable operational impacts, such as enhancing integrated deterrence capabilities, though critics note that such honors are commonplace for four-star officers in high-visibility positions, potentially diluting their distinction beyond standard bureaucratic recognition.[49] For his tenure as Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from August 31, 2007, to August 3, 2011, Cartwright received one Army Distinguished Service Medal, one Navy Distinguished Service Medal, one Air Force Distinguished Service Medal, and one Coast Guard Distinguished Service Medal, each citing exceptionally meritorious service in joint leadership that advanced national defense priorities.[49][50] He also accumulated four Defense Distinguished Service Medals (with three bronze oak leaf clusters), the fourth presented at his retirement ceremony on August 30, 2011, for sustained contributions to strategic innovation amid evolving threats.[49][50] These reflect documented efficiencies in command structures but align with routine accolades for flag-rank tenure rather than singular battlefield valor.[49]| Award | Number of Awards | Context |

|---|---|---|

| Defense Distinguished Service Medal | 4 (with 3 bronze oak leaf clusters) | Meritorious service in national security roles, culminating in 2011 retirement presentation.[49][50] |

| Legion of Merit | 2 (with 1 gold star) | Outstanding aviation and strategic command leadership.[49] |

| Army/Navy/Air Force/Coast Guard Distinguished Service Medals | 1 each | Joint Chiefs service enhancing inter-service coordination.[49][50] |