Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Acid catalysis

View on Wikipedia

In acid catalysis and base catalysis, a chemical reaction is catalyzed by an acid or a base. By Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, the acid is the proton (hydrogen ion, H+) donor and the base is the proton acceptor. Typical reactions catalyzed by proton transfer are esterifications and aldol reactions. In these reactions, the conjugate acid of the carbonyl group is a better electrophile than the neutral carbonyl group itself. Depending on the chemical species that act as the acid or base, catalytic mechanisms can be classified as either specific catalysis and general catalysis. Many enzymes operate by general catalysis.

Applications and examples

[edit]Brønsted acids

[edit]Acid catalysis is mainly used for organic chemical reactions. Many acids can function as sources for the protons. Acid used for acid catalysis include hydrofluoric acid (in the alkylation process), phosphoric acid, toluenesulfonic acid, polystyrene sulfonate, heteropoly acids, zeolites.

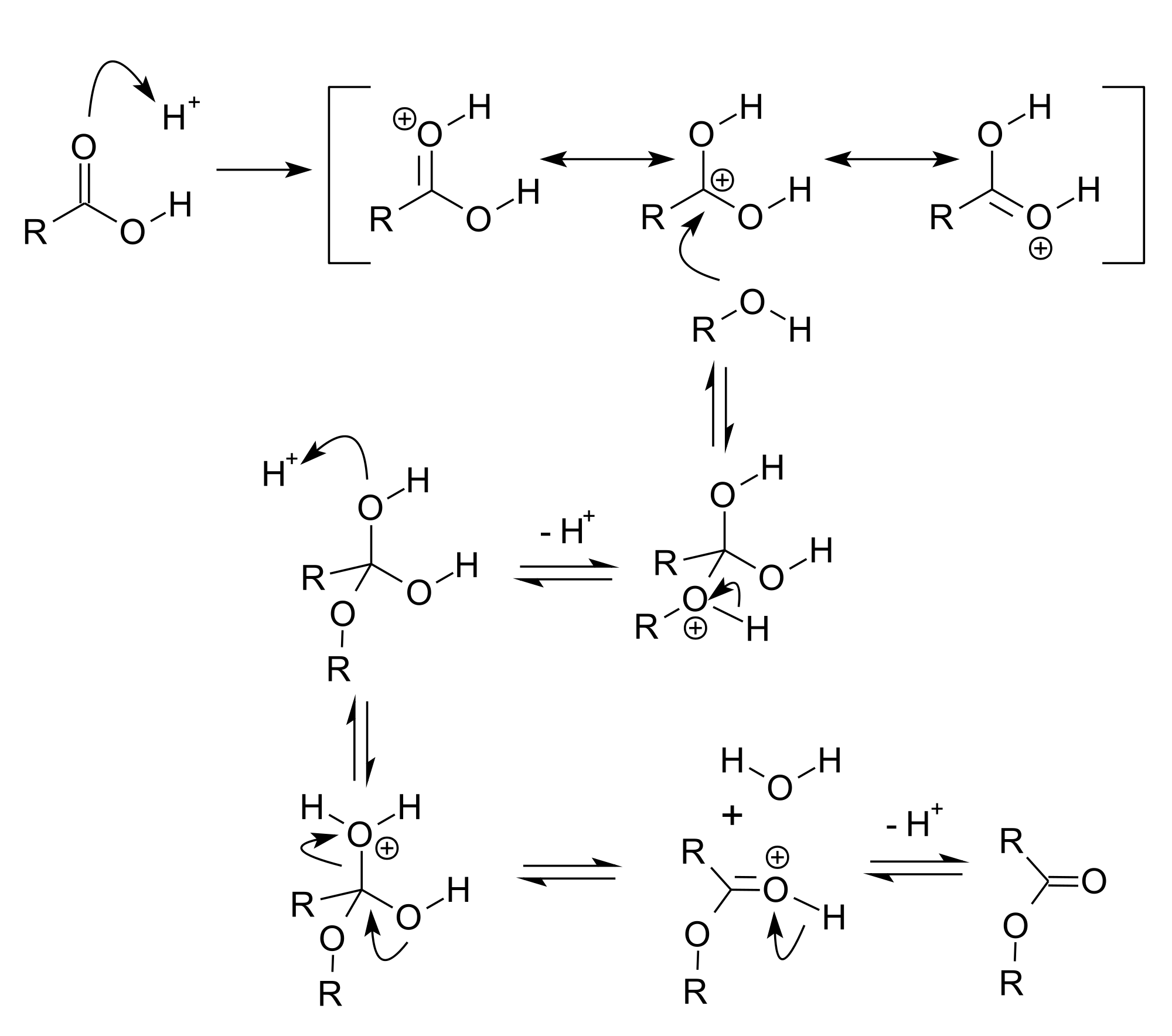

Strong acids catalyze the hydrolysis and transesterification of esters, e.g. for processing fats into biodiesel. In terms of mechanism, the carbonyl oxygen is susceptible to protonation, which enhances the electrophilicity at the carbonyl carbon.

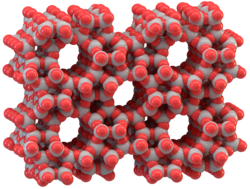

Solid acid catalysts

[edit]

In industrial scale chemistry, many processes are catalysed by "solid acids". Solid acids do not dissolve in the reaction medium. Well known examples include these oxides, which function as Lewis acids: silico-aluminates (zeolites, alumina, silico-alumino-phosphate), sulfated zirconia, and many transition metal oxides (titania, zirconia, niobia, and more). Such acids are used in cracking. Many solid Brønsted acids are also employed industrially, including sulfonated polystyrene, sulfonated carbon,[1][2] solid phosphoric acid, niobic acid, and heteropolyoxometallates.[3]

A particularly large scale application is alkylation, e.g., the combination of benzene and ethylene to give ethylbenzene. Another major application is the rearrangement of cyclohexanone oxime to caprolactam.[4] Many alkylamines are prepared by amination of alcohols, catalyzed by solid acids. In this role, the acid converts, OH−, a poor leaving group, into a good one. Thus acids are used to convert alcohols into other classes of compounds, such as thiols and amines.

Mechanism

[edit]Two kinds of acid catalysis are recognized, specific acid catalysis and general acid catalysis.[5]

Specific catalysis

[edit]In specific acid catalysis, protonated solvent is the catalyst. The reaction rate is proportional to the concentration of the protonated solvent molecules SH+.[6] The acid catalyst itself (AH) only contributes to the rate acceleration by shifting the chemical equilibrium between solvent S and AH in favor of the SH+ species. This kind of catalysis is common for strong acids in polar solvents, such as water.

For example, in an aqueous buffer solution the reaction rate for reactants R depends on the pH of the system but not on the concentrations of different acids.

This type of chemical kinetics is observed when reactant R1 is in a fast equilibrium with its conjugate acid R1H+ which proceeds to react slowly with R2 to the reaction product; for example, in the acid catalysed aldol reaction.

General catalysis

[edit]In general acid catalysis all species capable of donating protons contribute to reaction rate acceleration.[7] The strongest acids are most effective. Reactions in which proton transfer is rate-determining exhibit general acid catalysis, for example diazonium coupling reactions.

When keeping the pH at a constant level but changing the buffer concentration a change in rate signals a general acid catalysis. A constant rate is evidence for a specific acid catalyst. When reactions are conducted in nonpolar media, this kind of catalysis is important because the acid is often not ionized.

Enzymes catalyze reactions using general-acid and general-base catalysis.

References

[edit]- ^ Lathiya, Dharmesh R.; Bhatt, Dhananjay V.; Maheria, Kalpana C. (June 2018). "Synthesis of sulfonated carbon catalyst from waste orange peel for cost effective biodiesel production". Bioresource Technology Reports. 2: 69–76. Bibcode:2018BiTeR...2...69L. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2018.04.007. S2CID 102573076.

- ^ Gómez Millán, Gerardo; Phiri, Josphat; Mäkelä, Mikko; Maloney, Thad; Balu, Alina M.; Pineda, Antonio; Llorca, Jordi; Sixta, Herbert (5 September 2019). "Furfural production in a biphasic system using a carbonaceous solid acid catalyst". Applied Catalysis A: General. 585 117180. Bibcode:2019AppCA.585k7180G. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2019.117180. hdl:2117/177256. S2CID 201217759.

- ^ Busca, Guido "Acid Catalysts in Industrial Hydrocarbon Chemistry" Chemical Reviews 2007, volume 107, 5366-5410. doi:10.1021/cr068042e

- ^ Michael Röper, Eugen Gehrer, Thomas Narbeshuber, Wolfgang Siegel "Acylation and Alkylation" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2000. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_185

- ^ Lowry, T. H.; Richardson, K. S., "Mechanism and Theory in Organic Chemistry," Harper and Row: 1981. ISBN 0-06-044083-X

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Specific catalysis". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05796

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "General acid catalysis". doi:10.1351/goldbook.G02609

![{\displaystyle {\text{rate}}=-{\frac {{\text{d}}[{\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{1}}]}{{\text{d}}t}}=k{[\mathrm {SH} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{1}]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{2}]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/75067096bad781d99c291bd99419700d6db53e81)

![{\displaystyle {\text{rate}}=-{\frac {{\text{d}}[{\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{1}}]}{{\text{d}}t}}=k_{1}{[\mathrm {SH} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{1}]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{2}]}+k_{2}{[\mathrm {A} {\mkern {2mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {1}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {1}}}\mathrm {H} ]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{1}]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{2}]}+k_{3}{[\mathrm {A} {\mkern {2mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} ]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{1}]~[\mathrm {R} {\vphantom {A}}^{2}]}+...}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2f442541d3f75dcc737cd9935b618de39267b6c)