Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

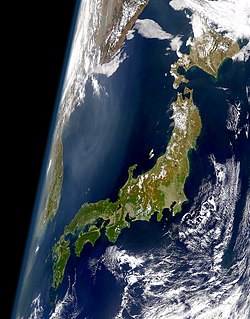

Geography of Japan

View on Wikipedia

Japan is an archipelagic country comprising a stratovolcanic archipelago over 3,000 km (1,900 mi) along the Pacific coast of East Asia.[8] It consists of 14,125 islands.[9][10] The five main islands are Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and Okinawa. The other 14,120 islands are classified as "remote islands" by the Japanese government.[9][11] The Ryukyu Islands and Nanpō Islands are south and east of the main islands.

Key Information

The territory covers 377,973.89 km2 (145,936.53 sq mi).[2] It is the fourth-largest island country in the world and the largest island country in East Asia.[12] The country has the 6th longest coastline at 29,751 km (18,486 mi) and the 8th largest Exclusive Economic Zone of 4,470,000 km2 (1,730,000 sq mi) in the world.[13]

The terrain is mostly rugged and mountainous, with 66% forest.[14] The population is clustered in urban areas along the coast, plains, and valleys.[15] Japan is located in the northwestern Ring of Fire on multiple tectonic plates.[16] East of the Japanese archipelago are three oceanic trenches. The Japan Trench is created as the oceanic Pacific Plate subducts beneath the continental Okhotsk Plate.[17] The continuous subduction process causes frequent earthquakes, tsunamis, and stratovolcanoes.[18] The islands are also affected by typhoons. The subduction plates have pulled the Japanese archipelago eastward, created the Sea of Japan, and separated it from the Asian continent by back-arc spreading 15 million years ago.[16]

The climate varies from humid continental in the north to humid subtropical and tropical rainforests in the south. These differences in climate and landscape have allowed the development of a diverse flora and fauna, with some rare endemic species, especially in the Ogasawara Islands.

Japan extends from 20° to 45° north latitude (Okinotorishima to Benten-jima) and from 122° to 153° east longitude (Yonaguni to Minami Torishima).[19] Japan is surrounded by seas. To the north, the Sea of Okhotsk separates it from the Russian Far East; to the west, the Sea of Japan separates it from the Korean Peninsula; to the southwest, the East China Sea separates the Ryukyu Islands from China and Taiwan; to the east is the Pacific Ocean.

The Japanese archipelago is over 3,000 km (1,900 mi) long in a north-to-southwardly direction from the Sea of Okhotsk to the Philippine Sea in the Pacific Ocean.[8] It is narrow, and no point in Japan is more than 150 km (93 mi) from the sea. In 2023, a government recount of the islands with digital maps increased the total from 6,852 to 14,125 islands.[9] The five main islands are (from north to south) Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, and Okinawa. Three of the four major islands (Honshu, Kyushu, and Shikoku) are separated by narrow straits of the Seto Inland Sea and form a natural entity. The 6,847 smaller islands are called remote islands.[10][11] This includes the Bonin Islands, Daitō Islands, Minami-Tori-shima, Okinotorishima, the Ryukyu Islands, the Volcano Islands, Nansei Islands, and the Nanpō Islands, as well as numerous islets, of which 430 are inhabited. The Senkaku Islands are administered by Japan but disputed by China. This excludes the disputed Northern Territories (Kuril Islands) and Liancourt Rocks. In total, as of 2021, Japan's territory is 377,973.89 km2 (145,936.53 sq mi), of which 364,546.41 km2 (140,752.16 sq mi) is land and 13,430 km2 (5,190 sq mi) is water.[2] Japan has the sixth longest coastline in the world (29,751 km (18,486 mi)). It is the largest island country in East Asia and the fourth largest island country in the world.[12]

Because of Japan's many far-flung outlying islands and long coastline, the country has extensive marine life and mineral resources in the ocean. The Exclusive Economic Zone of Japan covers 4,470,000 km2 (1,730,000 sq mi) and is the 8th largest in the world. It is more than 11 times the land area of the country.[13] The Exclusive Economic Zone stretches from the baseline out to 200 nautical miles (370 km) from its coast. Its territorial sea is 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi), but between 3 and 12 nmi (5.6 and 22.2 km; 3.5 and 13.8 mi) in the international straits—La Pérouse (or Sōya Strait), Tsugaru Strait, Ōsumi, and Tsushima Strait.

Japan has a population of 126 million as of 2019.[20] It is the 11th most populous country in the world and the second most populous island country.[12] 81% of the population lives on Honshu, 10% on Kyushu, 4.2% on Hokkaido, 3% on Shikoku, 1.1% in Okinawa Prefecture, and 0.7% on other Japanese islands such as the Nanpō Islands.

Map of Japan

[edit]

Japan is formally divided into eight regions, from northeast (Hokkaidō) to southwest (Ryukyu Islands):[21]

- Hokkaido

- Tōhoku region

- Kantō region

- Chūbu region

- Kansai (or Kinki) region

- Chūgoku region

- Shikoku

- Kyūshū

Each region contains several prefectures, except the Hokkaido region, which comprises only Hokkaido Prefecture.

The regions are not official administrative units but have been traditionally used as the regional division of Japan in a number of contexts. For example, maps and geography textbooks divide Japan into the eight regions; weather reports usually give the weather by region; and many businesses and institutions use their home region as part of their name (Kinki Nippon Railway, Chūgoku Bank, Tohoku University, etc.). While Japan has eight High Courts, their jurisdictions do not correspond with the eight regions.

Composition, topography and geography

[edit]

About 73% of Japan is mountainous,[22] with a mountain range running through each of the main islands. Japan's highest mountain is Mount Fuji, with an elevation of 3,776 m (12,388 ft). Japan's forest cover rate is 68.55% since the mountains are heavily forested. The only other developed nations with such a high forest cover percentage are Finland and Sweden.[14]

Since there is little level ground, many hills and mountainsides at lower elevations around towns and cities are often cultivated. As Japan is situated in a volcanic zone along the Pacific deeps, frequent low-intensity earth tremors and occasional volcanic activity are felt throughout the islands. Destructive earthquakes occur several times a century. Hot springs are numerous and have been exploited by the leisure industry.

The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan measures Japan's territory annually in order to continuously grasp the state of the national land. As of July 1, 2021, Japan's territory is 377,973.89 square kilometres (145,936.53 sq mi). It increases in area due to volcanic eruptions such as Nishinoshima (西之島), the natural expansion of the islands, and land reclamation.[2]

This table shows land use in 2002.[23]

| Forest | Agricultural land | Residential area | Water surface, rivers, waterways | Roads | Wilderness | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66.4% | 12.8% | 4.8% | 3.6% | 3.4% | 0.7% | 8.3% |

| 251,000 km2 (97,000 sq mi) | 48,400 km2 (18,700 sq mi) | 18,100 km2 (7,000 sq mi) | 13,500 km2 (5,200 sq mi) | 13,000 km2 (5,000 sq mi) | 2,600 km2 (1,000 sq mi) | 31,300 km2 (12,100 sq mi) |

Location

[edit]The Japanese archipelago is relatively far away from the Asian continent. Kyushu is closest to the southernmost point of the Korean peninsula, with a distance of 190 km (120 mi), which is almost six times farther away than from England to France across the English Channel. Thus, historically, Kyushu was the gateway between Asia and Japan. China is separated by 800 km (500 mi) of sea from Japan's big main islands. Hokkaido is near Sakhalin, which was occupied by Japan from 1905 to 1945. Most of the population lives on the Pacific coast of Honshū. The west coast facing the Sea of Japan is less densely populated.[24]

The Japanese archipelago has been difficult to reach since ancient history. During the Paleolithic period around 20,000 BCE, at the height of the Last Glacial Maximum, there was a land bridge between Hokkaido and Sakhalin that linked Japan with the Asian continent. The land bridge disappeared when sea levels rose in the Jōmon period around 10,000 BCE.[25]

Japan's remote location, surrounded by vast seas, rugged, mountainous terrain, and steep rivers, makes it secure against invaders and uncontrolled migration from the Asian continent. The Japanese can close their civilization with an isolationist foreign policy. During the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shogunate enforced the Sakoku policy, which prohibited most foreign contact and trade from 1641 to 1853.[26] In modern times, the inflow of people is managed via seaports and airports. Thus, Japan is fairly insulated from continental issues.

Throughout history, Japan has never been fully invaded or colonized by other countries. The Mongols tried to invade Japan twice and failed in 1274 and 1281. Japan capitulated only once after nuclear attacks in World War II. At the time, Japan did not have nuclear technology. The insular geography is a major factor in the isolationist, semi-open, and expansionist periods of Japanese history.

Mountains and volcanoes

[edit]The mountainous islands of the Japanese archipelago form a crescent off the eastern coast of Asia.[27] They are separated from the continent by the Sea of Japan, which serves as a protective barrier. Japan has 108 active volcanoes (10% of the world's active volcanoes) because of active plate tectonics in the Ring of Fire.[18]

Around 15 million years ago, the volcanic shoreline of the Asian continent was pushed out into a series of volcanic island arcs.[16] This created the "back-arc basins" known as the Sea of Japan and Sea of Okhotsk with the formal shaping of the Japanese archipelago.[16] The archipelago also has summits on mountain ridges that were uplifted near the outer edge of the continental shelf.[27] About 73 percent of Japan's area is mountainous, and scattered plains and intermontane basins (in which the population is concentrated) cover only about 27 percent.[27] A long chain of mountains runs down the middle of the archipelago, dividing it into two halves: the "face", facing the Pacific Ocean, and the "back", toward the Sea of Japan.[27] On the Pacific side are steep mountains 1,500 to 3,000 meters high, with deep valleys and gorges.[27]

Central Japan is marked by the convergence of the three mountain chains—the Hida, Kiso, and Akaishi mountains—that form the Japanese Alps (Nihon Arupusu), several of whose peaks are higher than 3,000 metres (9,800 ft).[27] The highest point in the Japanese Alps is Mount Kita at 3,193 metres (10,476 ft).[27] The highest point in the country is Mount Fuji (Fujisan, also erroneously called Fujiyama), a volcano dormant since 1707 that rises to 3,776 m (12,388 ft) above sea level in Shizuoka Prefecture.[27] On the Sea of Japan side are plateaus and low mountain districts, with altitudes of 500 to 1,500 meters.[27]

Plains

[edit]

There are three major plains in central Honshū. The largest is the Kantō Plain, which covers 17,000 km2 (6,600 sq mi) in the Kantō region. The capital Tokyo and the largest metropolitan population are located there. The second largest plain in Honshū is the Nōbi Plain (1,800 km2 (690 sq mi)), with the third-most-populous urban area being Nagoya. The third-largest plain in Honshū is the Osaka Plain, which covers 1,600 km2 (620 sq mi) in the Kinki region. It features the second-largest urban area of Osaka (part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area). Osaka and Nagoya extend inland from their bays until they reach steep mountains. The Osaka Plain is connected with Kyoto and Nara. Kyoto is located in the Yamashiro Basin (827.9 km2 (319.7 sq mi)) and Nara is in the Nara Basin (300 km2 (120 sq mi)).

The Kantō Plain, Osaka Plain, and Nōbi Plain are the most important economic, political, and cultural areas of Japan. These plains had the largest agricultural production and large bays with ports for fishing and trade. This made them the largest population centers. Kyoto and Nara are the ancient capitals and cultural heart of Japan. The Kantō Plain became Japan's center of power because it is the largest plain with a central location, and historically, it had the most agricultural production that could be taxed. The Tokugawa Shogunate established a bakufu in Edo in 1603.[28] This evolved into the capital of Tokyo by 1868.

Hokkaido has multiple plains, such as the Ishikari Plain (3,800 km2 (1,500 sq mi)), Tokachi Plain (3,600 km2 (1,400 sq mi)), the Kushiro Plain, the largest wetland in Japan (2,510 km2 (970 sq mi)), and the Sarobetsu Plain (200 km2 (77 sq mi)). There are many farms that produce a plethora of agricultural products. The average farm size in Hokkaido was 26 hectares per farmer in 2013. That is nearly 11 times larger than the national average of 2.4 hectares. This made Hokkaido the most agriculturally rich prefecture in Japan.[29] Nearly one-fourth of Japan's arable land and 22% of Japan's forests are in Hokkaido.[30]

Another important plain is the Sendai Plain around the city of Sendai in northeastern Honshū.[27] Many of these plains are along the coast, and their areas have been increased by land reclamation throughout recorded history.[27]

Rivers

[edit]

Rivers are generally steep and swift, and few are suitable for navigation except in their lower reaches. Although most rivers are less than 300 km (190 mi) in length, their rapid flow from the mountains is what provides hydroelectric power.[27] Seasonal variations in flow have led to the extensive development of flood control measures.[27] The longest, the Shinano River, which winds through Nagano Prefecture to Niigata Prefecture and flows into the Sea of Japan, is 367 km (228 mi) long.[27][31]

These are the 10 longest rivers of Japan.[31]

| Rank | Name | Region | Prefecture | Length

(km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shinano | Hokuriku | Nagano, Niigata | 367 |

| 2 | Tone | Kantō | Saitama, Chiba, Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma | 322 |

| 3 | Ishikari | Hokkaido | Hokkaido | 268 |

| 4 | Teshio | Hokkaido | Hokkaido | 256 |

| 5 | Kitakami | Tōhoku | Iwate, Miyagi | 249 |

| 6 | Abukuma | Tōhoku | Fukushima, Miyagi | 239 |

| 7 | Mogami | Tōhoku | Yamagata | 229 |

| 8 | Tenryu | Chūbu | Nagano, Aichi, Shizuoka | 212 |

| 9 | Agano | Hokuriku | Niigata | 210 |

| 10 | Shimanto | Shikoku | Kōchi | 196 |

Lakes and coasts

[edit]

The largest freshwater lake is Lake Biwa (670.3 km2 (258.8 sq mi)), northeast of Kyoto in Shiga Prefecture.[32] Lake Biwa is an ancient lake and is estimated to be the 13th oldest lake in the world, dating to at least 4 million years ago.[33][32] It has consistently carried water for millions of years. Lake Biwa was created by plate tectonics in an active rift zone. This created a very deep lake with a maximum depth of 104 m (341 ft). Thus, it is not naturally filled with sediment. Over the course of millions of years, a diverse ecosystem evolved in the lake. It has more than 1,000 species and subspecies. There are 46 native fish species and subspecies,[34] including 11 species and 5 subspecies that are endemic or near-endemic.[32] Approximately 5,000 water birds visit the lake each year.

The following are the 10 largest lakes of Japan.[35]

Extensive coastal shipping, especially around the Seto Inland Sea, compensates for the lack of navigable rivers.[27] The Pacific coastline south of Tokyo is characterized by long, narrow, gradually shallowing inlets produced by sedimentation, which has created many natural harbors.[27] The Pacific coastline north of Tokyo, the coast of Hokkaido, and the Sea of Japan coast are generally unindented, with few natural harbors.[27]

A recent global remote sensing analysis suggested that there were 765 km2 of tidal flats in Japan, making it the 35th-ranked country in terms of tidal flat extent.[36]

Land reclamation

[edit]

The Japanese archipelago has been transformed by humans into a sort of continuous land, in which the four main islands are entirely reachable and passable by rail and road transportation thanks to the construction of huge bridges and tunnels that connect each other and various islands.[37]

Approximately 0.5% of Japan's total area is reclaimed land (umetatechi).[38] It began in the 12th century.[38] Land was reclaimed from the sea and from river deltas by building dikes, drainage, and rice paddies on terraces carved into mountainsides.[27] The majority of land reclamation projects occurred after World War II, during the Japanese economic miracle. Reclamation of 80% to 90% of all the tidal flatland was done. Large land reclamation projects with landfills were done in coastal areas for maritime and industrial factories, such as Higashi Ogishima in Kawasaki, Osaka Bay, and Nagasaki Airport. Port Island, Rokkō Island, and Kobe Airport were built in Kobe. Late 20th and early 21st century projects include artificial islands such as Chubu Centrair International Airport in Ise Bay, Kansai International Airport in the middle of Osaka Bay, Yokohama Hakkeijima Sea Paradise, and Wakayama Marina City.[38] The village of Ōgata in Akita was established on land reclaimed from Lake Hachirōgata (Japan's second largest lake at the time) starting in 1957. By 1977, the amount of land reclaimed totaled 172.03 square kilometres (66.42 sq mi).[39]

Examples of land reclamation in Japan include:

- Kyogashima, Kobe – the first human-made island built by Taira no Kiyomori in 1173[38]

- The Hibiya Inlet, Tokyo – the first large-scale reclamation project started in 1592[38]

- Dejima, Nagasaki – built during Japan's national isolation period in 1634. It was the sole trading post in Japan during the Sakoku period and was originally inhabited by Portuguese and then Dutch traders.[38]

- Tokyo Bay, Japan – 249 square kilometres (96 sq mi)[40] artificial island (2007)

- Kobe, Japan – 23 square kilometres (8.9 sq mi) (1995).[38]

- Isahaya Bay in the Ariake Sea – approximately 35 square kilometres (14 sq mi) is reclaimed with tide embankment and sluice gates (2018).

- Yumeshima, Osaka – 390 hectares (960 acres) artificial island (2025)

- Central Breakwater – 989 hectares (2,440 acres)

Much reclaimed land is made up of landfill waste materials, dredged earth, sand, sediment, sludge, and soil removed from construction sites. It is used to build human-made islands in harbors and embankments in inland areas.[38] On November 8, 2011, Tokyo City began accepting rubble and waste from the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami region. This rubble was processed, and when it had the appropriate radiation levels, it was used as a landfill to build new artificial islands in Tokyo Bay. Yamashita Park in Yokohama City was made with rubble from the great Kantō earthquake in 1923.[38]

There is a risk of contamination on artificial islands with landfills and reclaimed land if there was industry that spilled toxic chemicals into the ground. For example, the artificial island of Toyosu was once occupied by a Tokyo gas factory. Toxic substances were discovered in the soil and groundwater at Toyosu. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government spent an additional 3.8 billion yen ($33.5 million) to pump out groundwater by digging hundreds of wells.[41] In June 2017, plans to move the Tsukiji fish market were restarted[42] but delayed from July to the autumn of 2018.[43] After the new site was declared safe following a cleanup operation, Toyosu Market was opened.[44]

Oceanography and seabed of Japan

[edit]

Japan's sea territory is 4,470,000 km2 (1,730,000 sq mi).[13] Japan ranks fourth with its exclusive economic zone ocean water volume from 0 to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) depth. Japan ranks fifth with a sea volume of 2,000–3,000 meters, fourth with 3,000–4,000 meters, third with 4,000–5,000 meters, and first with a volume of 5,000 to over 6,000 meters. The relief map of the Japanese archipelago shows that 50% of Japan's sea territory has an ocean volume between 0 and 4,000 m (13,000 ft) deep. The other 50% has a depth of 4,000 m (13,000 ft) to over 6,000 m (20,000 ft). 19% has a depth of 0 to 1,000 m (3,300 ft). Thus, Japan possesses one of the largest ocean territories with a combination of all depths, from shallow to very deep.[6] Multiple long undersea mountain ranges stretch from Japan's main islands to the south. They occasionally reach above the sea surface as islands. East of the undersea mountain ranges are three oceanic trenches: the Kuril–Kamchatka Trench (max depth 10,542 m (34,587 ft)), Japan Trench (max depth 10,375 m (34,039 ft)), and Izu–Ogasawara Trench (max depth 9,810 m (32,190 ft)).

There are large quantities of marine life and mineral resources in the ocean and seabed of Japan. At a depth of over 1,000 m (3,300 ft), there are minerals such as manganese nodules, cobalt in the crust, and hydrothermal deposits. Within the island straits remarkable subaqueous dunes are present on the shelf.[45]

Geology

[edit]

Tectonic plates

[edit]The Japanese archipelago is the result of subducting tectonic plates over several 100 million years, from the mid-Silurian (443.8 Mya) to the Pleistocene (11,700 years ago). Approximately 15,000 km (9,300 mi) of oceanic floor has passed under the Japanese archipelago in the last 450 million years, with most being fully subducted. It is considered a mature island arc.

The islands of Japan were created by tectonic plate movements:

- Tohoku (upper half of Honshu), Hokkaido, the Kuril Islands, and Sakhalin are located on the Okhotsk Plate. This is a minor tectonic plate bounded to the north by the North American Plate.[46][47] The Okhotsk Plate is bounded on the east by the Pacific Plate at the Kuril–Kamchatka Trench and the Japan Trench. It is bounded on the south by the Philippine Sea Plate at the Nankai Trough. On the west, it is bound by the Eurasian Plate, and possibly on the southwest, by the Amurian Plate. The northeastern boundary is the Ulakhan Fault.[48]

- The southern half of Honshu, Shikoku, and most of Kyushu are located on the Amurian Plate.

- The southern tip of Kyushu and the Ryukyu islands are located on the Okinawa Plate.

- The Nanpō Islands are on the Philippine Sea Plate.

The Pacific Plate and Philippine Sea Plate are subduction plates. They are deeper than the Eurasian plate. The Philippine Sea Plate moves beneath the continental Amurian Plate and the Okinawa Plate to the south. The Pacific Plate moves under the Okhotsk Plate to the north. These subduction plates pulled Japan eastward and opened the Sea of Japan by back-arc spreading around 15 million years ago.[16] The Strait of Tartary and the Korea Strait opened much later. La Pérouse Strait formed about 60,000 to 11,000 years ago, closing the path used by mammoths, which had earlier moved to northern Hokkaido.[49] The eastern margin of the Sea of Japan is an incipient subduction zone consisting of thrust faults that formed from the compression and reactivation of old faults involved in earlier rifting.[50]

The subduction zone is where the oceanic crust slides beneath the continental crust or other oceanic plates. This is because the oceanic plate's lithosphere has a higher density. Subduction zones are sites that usually have a high rate of volcanism and earthquakes.[51] Additionally, subduction zones develop belts of deformation.[52] The subduction zones on the east side of the Japanese archipelago cause frequent low-intensity earth tremors. Major earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis occur several times per century. It is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire.[16] Northeastern Japan, north of the Tanakura fault, had high volcanic activity 14–17 million years before the present.[53]

Median Tectonic Line

[edit]

The Japan Median Tectonic Line (MTL) is Japan's longest fault system.[54][55] The MTL begins near Ibaraki Prefecture, where it connects with the Itoigawa-Shizuoka Tectonic Line (ISTL) and the Fossa Magna. It runs parallel to Japan's volcanic arc, passing through central Honshū to near Nagoya, through Mikawa Bay, then through the Seto Inland Sea from the Kii Channel and Naruto Strait to Shikoku along the Sadamisaki Peninsula and the Bungo Channel and Hōyo Strait to Kyūshū.[55]

The MTL moves right-lateral strike-slip at about 5–10 millimeters per year.[56] The sense of motion is consistent with the direction of the Nankai Trough's oblique convergence. The rate of motion on the MTL is much less than the rate of convergence at the plate boundary. This makes it difficult to distinguish the motion on the MTL from interseismic elastic straining in GPS data.[57]

Oceanic trenches

[edit]

East of the Japanese archipelago are three oceanic trenches.

- The Kuril–Kamchatka Trench is in the northwest Pacific Ocean. It lies off the southeast coast of Kamchatka and parallels the Kuril Island chain to meet the Japan Trench east of Hokkaido.[58]

- The Japan Trench extends 8,000 km (4,971 mi) from the Kuril Islands to the northern end of the Izu Islands. Its deepest part is 8,046 m (26,398 ft).[59] The Japan Trench is created as the oceanic Pacific Plate subducts beneath the continental Okhotsk Plate. The subduction process causes bending of the down-going plate, creating a deep trench. Continuous movement on the subduction zone associated with the Japan Trench is one of the main causes of tsunamis and earthquakes in northern Japan, including the megathrust 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. The rate of subduction associated with the Japan Trench has been recorded at about 7.9–9.2 cm (3.1–3.6 in)/year.[17]

- The Izu–Ogasawara Trench is south of the Japan Trench in the western Pacific Ocean. It consists of the Izu Trench (at the north) and the Bonin Trench (at the south, west of the Ogasawara Plateau).[60] It stretches to the northernmost section of the Mariana Trench.[61] The Izu–Ogasawara Trench is an extension of the Japan Trench. There, the Pacific Plate is being subducted beneath the Philippine Sea Plate, creating the Izu Islands and Bonin Islands on the Izu–Bonin–Mariana Arc system.[62]

Composition

[edit]The Japanese islands are formed of the mentioned geological units parallel to the subduction front. The parts of islands facing the Pacific Plate are typically younger and display a larger proportion of volcanic products, while island parts facing the Sea of Japan are mostly heavily faulted and folded sedimentary deposits. In northwest Japan, there are thick quaternary deposits. This makes the determination of the geological history and composition difficult, and it is not yet fully understood.[63]

The Japanese island arc system has distributed volcanic series where the volcanic rocks change from tholeiite—calc-alkaline—alkaline with increasing distance from the trench.[64][65] The geologic province of Japan is mostly basin and has a bit of extended crust.[66]

Growing archipelago

[edit]The Japanese archipelago grows gradually because of perpetual tectonic plate movements, earthquakes, stratovolcanoes, and land reclamation in the Ring of Fire.

For example, during the 20th century, several new volcanoes emerged, including Shōwa-shinzan on Hokkaido and Myōjin-shō off the Bayonnaise Rocks in the Pacific.[18] The 1914 Sakurajima eruption produced lava flows that connected the former island with the Ōsumi Peninsula in Kyushu.[67] It is the most active volcano in Japan.[68]

During the 2013 eruption southeast of Nishinoshima, a new, unnamed volcanic island emerged from the sea.[69] Erosion and shifting sands caused the new island to merge with Nishinoshima.[70][71] A 1911 survey determined the caldera was 107 m (351 ft) at its deepest.[72]

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami caused portions of northeastern Japan to shift by 2.4 metres (7 ft 10 in) closer to North America.[73] This made some sections of Japan's landmass wider than before.[74] The areas of Japan closest to the epicenter experienced the largest shifts.[74] A 400-kilometre (250 mi) stretch of coastline dropped vertically by 0.6 metres (2 ft 0 in), allowing the tsunami to travel farther and faster onto land.[74] On 6 April, the Japanese coast guard said that the earthquake shifted the seabed near the epicenter 24 metres (79 ft) and elevated the seabed off the coast of Miyagi Prefecture by 3 metres (9.8 ft).[75] A report by the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, published in Science on 2 December 2011, concluded that the seabed in the area between the epicenter and the Japan Trench moved 50 metres (160 ft) east-southeast and rose about 7 metres (23 ft) as a result of the quake. The report also stated that the quake caused several major landslides on the seabed in the affected area.[76]

Sea of Japan

[edit]

History

[edit]During the Pleistocene (spanning 2.58 million-11,700 years ago) glacial cycles, the Japanese islands may have occasionally been connected to the Eurasian Continent via the Korea Strait and the Korean Peninsula or Sakhalin. The Sea of Japan was considered to be a frozen inner lake because of the lack of the warm Tsushima Current. Various plants and large animals, such as the elephant Palaeoloxodon naumanni, migrated into the Japanese archipelago.[77]

The Sea of Japan was a landlocked sea when the land bridge of East Asia existed circa 18,000 BCE. During the glacial maximum, the marine elevation was 200 meters lower than present. Thus, Tsushima island in the Korea Strait was a land bridge that connected Kyushu and the southern tip of Honshu with the Korean peninsula. There were still several kilometers of sea to the west of the Ryukyu islands, and most of the Sea of Japan was open sea with a mean depth of 1,752 m (5,748 ft). Comparatively, most of the Yellow Sea (Yellow Plane) had a semi-arid climate (dry steppe) because it was relatively shallow, with a mean depth of 44 m (144 ft). The Korean Peninsula was landlocked on the entire west and south sides of the Yellow Plane.[78] The onset of the formation of the Japan Arc was in the Early Miocene (23 million years ago).[79] The Early Miocene period was when the Sea of Japan started to open and the northern and southern parts of the Japanese archipelago separated from each other.[79] The Sea of Japan expanded during the Miocene.[79]

The northern part of the Japanese archipelago was further fragmented until the orogenesis of the northeastern Japanese archipelago began in the Late Miocene. The orogenesis of the high mountain ranges in northeastern Japan started in the Late Miocene and lasted into the Pliocene.[79] The southern part of the Japanese archipelago remained a relatively large landmass. The land area expanded northward during the Miocene.[79]

During the advance of the last Ice Age, the world sea level dropped. This dried up and closed the exit straits of the Sea of Japan one by one. The deepest, and thus the last to close, was the western channel of the Korea Strait. There is controversy as to whether the Sea of Japan became a huge, cold inland lake.[77] The Japanese archipelago had a taiga biome (open boreal woodlands). It was characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces, and larches. Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril islands had mammoth steppe biome (steppe-tundra). The vegetation was dominated by palatable high-productivity grasses, herbs, and willow shrubs.

Present

[edit]The Sea of Japan has a surface area of 978,000 km2 (378,000 sq mi), a mean depth of 1,752 m (5,748 ft), and a maximum depth of 3,742 m (12,277 ft). It has a carrot-like shape, with the major axis extending from southwest to northeast and a wide southern part narrowing toward the north. The coastal length is about 7,600 km (4,700 mi), with the largest part (3,240 km or 2,010 mi) belonging to Russia. The sea extends from north to south for more than 2,255 km (1,401 mi) and has a maximum width of about 1,070 km (660 mi).[80]

There are three major basins: the Yamato Basin in the southeast, the Japan Basin in the north, and the Tsushima Basin in the southwest.[49] The Japan Basin has an oceanic crust and is the deepest part of the sea, whereas the Tsushima Basin is the shallowest, with depths below 2,300 m (7,500 ft). The Yamato Basin and Tsushima Basin have thick oceanic crusts.[80] The continental shelves of the sea are wide on the eastern shores of Japan. On the western shores, they are narrow, particularly along the Korean and Russian coasts, averaging about 30 km (19 mi).

The geographical location of the Japanese archipelago has defined the Sea of Japan for millions of years. Without the Japanese archipelago, it would just be the Pacific Ocean. The term has been the international standard since at least the early 19th century.[81] In 2012, the International Hydrographic Organization, the international governing body for naming bodies of water around the world, recognized the term "Sea of Japan" as the only title for the sea.[82]

Ocean currents

[edit]

The Japanese archipelago is surrounded by eight ocean currents.

- The Kuroshio (黒潮 ("くろしお"), "Black Tide") is a warm, north-flowing ocean current on the west side of the Ryukyu Islands and along the east coast of Kyushu, Shikoku, and Honshu. It is a strong western boundary current and part of the North Pacific ocean gyre.

- The Kuroshio Current starts on the east coast of Luzon, Philippines, past Taiwan, and flows northeastward past Japan, where it merges with the easterly drift of the North Pacific Current.[83] It transports warm, tropical water northward toward the polar region. The Kuroshio extension is a northward continuation of the Kuroshio Current in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. The Kuroshio countercurrent flows southward to the east of the Kuroshio current in the Pacific Ocean and Philippine Sea.

- The winter-spawning Japanese Flying Squid are associated with the Kuroshio Current. The eggs and larvae develop during winter in the East China Sea, and the adults travel with minimum energy via the Kuroshio Current to the rich northern feeding grounds near northwestern Honshu and Hokkaido.[84]

- The Tsushima Current (対馬海流, Tsushima Kairyū) is a branch of the Kuroshio Current. It flows along the west coast of Kyushu and Honshu into the Sea of Japan.

- The Oyashio (親潮; "Parental Tide") current is a cold subarctic ocean current that flows southward and circulates counterclockwise along the east coast of Hokkaido and northeastern Honshu in the western North Pacific Ocean. The waters of the Oyashio Current originate in the Arctic Ocean and flow southward via the Bering Sea, passing through the Bering Strait and transporting cold water from the Arctic Sea into the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk. It collides with the Kuroshio Current off the eastern shore of Japan to form the North Pacific Current. The nutrient-rich Oyashio is named for its metaphorical role as the parent (親, oya) that provides for and nurtures marine organisms.[85][86]

- The Liman Current is a southward-flowing cold ocean current that flows from the Strait of Tartary along the Asian continent in the Sea of Japan.[87]

- The Tsugaru Warm Current (津軽暖流, Tsugaru Danryū) originates when the Tsushima Current is divided in two as it flows through the west entrance of the Tsugaru Strait, and along the La Perouse Strait at the north coast of Hokkaido it becomes the Sōya Warm Current (宗谷暖流, Sōya Danryū). The flow rate is 1 to 3 knots. There is a relatively stronger flow in the summer than in the winter.[88]

Natural resources

[edit]Land resources

[edit]There are small deposits of coal, oil, iron, and minerals in the Japanese archipelago.[3] Japan is scarce in critical natural resources and has long been heavily dependent on imported energy and raw materials.[3][89] The oil crisis in 1973 encouraged the efficient use of energy.[90] Japan has therefore aimed to diversify its sources and maintain high levels of energy efficiency.[91] In regards to agricultural products, the self-sufficiency rate of most items is less than 100%, except for rice. Rice has 100% food self-sufficiency. This makes it difficult to meet Japan's food demand without imports.

Marine resources

[edit]

The exclusive economic zone of Japan has an estimated large quantity of mineral resources such as methane clathrate, natural gas, metallic minerals, and rare-earth mineral reserves. Seabed mineral resources such as manganese nodules, cobalt-rich crust, and submarine hydrothermal deposits are located at depths over 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[6] Most of these deep-sea resources are unexplored at the seabed. Japan's mining law restricts offshore oil and gas production. There are technological hurdles to mine at such extreme depths and to limit the ecological impact. There are no successful commercial ventures that mine the deep sea yet. So currently, there are few deep sea mining projects to retrieve minerals or deepwater drilling on the ocean floor.

It is estimated that there are approximately 40 trillion cubic feet of methane clathrate in the eastern Nankai Trough of Japan.[92] As of 2019, the methane clathrate in the deep sea remains unexploited because the necessary technology has not been established yet. This is why, currently, Japan has very limited proven reserves like crude oil.

The Kantō region alone is estimated to have over 400 billion cubic meters of natural gas reserves. It forms a Minami Kantō gas field in the area spanning Saitama, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Ibaraki, and Chiba prefectures. However, mining is strictly regulated in many areas because it is directly below Tokyo and is only slightly mined on the Bōsō Peninsula. In Tokyo and Chiba Prefecture, there have been frequent accidents with natural gas that was released naturally from the Minami Kantō gas field.[93]

In 2018, 250 km (160 mi) south of Minami-Tori-shima at 5,700 m (18,700 ft) deep, approximately 16 million tons of rare-earth minerals were discovered by JAMSTEC in collaboration with Waseda University and the University of Tokyo.[94]

Marine life

[edit]Japan maintains one of the world's largest fishing fleets and accounts for nearly 15% of the global catch (2014).[3] In 2005, Japan ranked sixth in the world in the tonnage of fish caught.[7] Japan captured 4,074,580 metric tons of fish in 2005, down from 4,987,703 tons in 2000 and 9,864,422 tons in 1980.[95] In 2003, the total aquaculture production was predicted at 1,301,437 tonnes.[96] In 2010, Japan's total fishery production was 4,762,469 fish.[97] Offshore fisheries accounted for an average of 50% of the nation's total fish catches in the late 1980s, although they experienced repeated ups and downs during that period.[27]

Energy

[edit]As of 2011[update], 46.1% of energy in Japan was produced from petroleum, 21.3% from coal, 21.4% from natural gas, 4.0% from nuclear power, and 3.3% from hydropower. Nuclear power is a major domestic source of energy and produced 9.2 percent of Japan's electricity as of 2011[update], down from 24.9 percent the previous year.[98] Following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami disaster, the nuclear reactors were shut down. Thus, Japan's industrial sector became even more dependent than before on imported fossil fuels. By May 2012, all of the country's nuclear power plants were taken offline because of ongoing public opposition following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in March 2011, though government officials continued to try to sway public opinion in favor of returning at least some of Japan's 50 nuclear reactors to service.[99] Shinzo Abe's government sook to restart the nuclear power plants that meet strict new safety standards and is emphasizing nuclear energy's importance as a base-load electricity source.[3] In 2015, Japan successfully restarted one nuclear reactor at the Sendai Nuclear Power Plant in Kagoshima prefecture, and several other reactors around the country have since resumed operations. Opposition from local governments has delayed several restarts that remain pending.

Reforms of the electricity and gas sectors, including the full liberalization of Japan's energy market in April 2016 and the gas market in April 2017, constitute an important part of Prime Minister Abe's economic program.[3]

Japan has the third-largest geothermal reserves in the world. Geothermal energy is being heavily focused on as a source of power following the Fukushima disaster. The Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry is exploring over 40 locations for potential geothermal energy plants.[100]

On 3 July 2018, Japan's government pledged to increase renewable energy sources from 15% to 22–24%, including wind and solar, by 2030. Nuclear energy will provide 20% of the country's energy needs as an emissions-free energy source. This will help Japan meet climate change commitments.[101]

National Parks and Scenic Beauty

[edit]National Parks

[edit]

Japan has 34 National Parks (国立公園, Kokuritsu Kōen) and 56 Quasi-National Parks (国定公園, Kokutei Kōen) in 2019. These are designated and managed for protection and sustainable usage by the Ministry of the Environment under the Natural Parks Law (自然公園法) of 1957.[102] The Quasi-National Parks have slightly less beauty, size, diversity, or preservation. They are recommended for ministerial designation and managed by the prefectures under the supervision of the Ministry of the Environment.[103]

The Japanese archipelago has diverse landscapes.[8] For example, the northern part of Hokkaido has a taiga biome.[104] Hokkaido has 22% of Japan's forestland with coniferous trees (Sakhalin fir and Sakhalin spruce) and broad-leaved trees (Japanese oak, birch, and painted maple). The seasonal views change throughout the year.[105] In the south, the Yaeyama Islands are in the subtropics, with numerous species of subtropical and tropical plants and mangrove forests.[106][107] Most natural islands have mountain ranges in the center and coastal plains.

- List of National Parks of Japan

- List of National Geoparks in Japan

- Wildlife Protection Areas in Japan

- List of Ramsar sites in Japan

- Cultural Landscapes

Places of Scenic Beauty

[edit]

The Places of Scenic Beauty and Natural Monuments are selected by the government via the Agency for Cultural Affairs in order to protect Japan's cultural heritage.[108] As of 2017, there are 1,027 Natural Monuments (天然記念物, tennen kinenbutsu) and 410 Places of Scenic Beauty (名勝, meishō). The highest classifications are 75 Special Natural Monuments (特別天然記念物, tokubetsu tennen kinenbutsu) and 36 Special Places of Scenic Beauty (特別名勝, tokubetsu meishō).

Three Views of Japan

[edit]The Three Views of Japan (日本三景, Nihon Sankei) is the canonical list of Japan's three most celebrated scenic sights, attributed to 1643 scholar Hayashi Gahō.[109] These are traditionally the pine-clad islands of Matsushima in Miyagi Prefecture, the pine-clad sandbar of Amanohashidate in Kyoto Prefecture, and Itsukushima Shrine in Hiroshima Prefecture. In 1915, the New Three Views of Japan were selected in a national election by the Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha (株式会社実業之日本社). In 2003, the Three Major Night Views of Japan were selected by the New Three Major Night Views of Japan and the 100 Night Views of Japan Club (新日本三大夜景・夜景100選事務局).

-

Pine-clad islands of Matsushima

-

Sandbar of Amanohashidate

Climate

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

Most regions of Japan, such as much of Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, belong to the temperate zone with a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) characterized by four distinct seasons. However, its climate varies from a cool, humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa/Dfb) in the north, such as northern Hokkaido, to a warm tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south, such as the Yaeyama Islands and Minami-Tori-shima.

Climate zones

[edit]

Japan's varied geographical features divide it into six principal climatic zones.

- Hokkaido belongs to the humid continental climate, with long, cold winters and cool summers. Precipitation is sparse; however, winter brings large snowfalls of hundreds of inches in areas such as Sapporo and Asahikawa.

- In the Sea of Japan, the northwest seasonal wind in winter gives heavy snowfall, which south of Tōhoku mostly melts before the beginning of spring. In summer, it is a little less rainy than in the Pacific area, but it sometimes experiences extreme high temperatures because of the foehn wind phenomenon.

- Central Highland: a typical inland climate gives large temperature variations between summers and winters and between days and nights. Precipitation is lower than on the coast because of rain shadow effects.

- Seto Inland Sea: the mountains in the Chūgoku and Shikoku regions block the seasonal winds and bring a mild climate and many fine days throughout the year.

- Pacific Ocean: the climate varies greatly between the north and the south, but generally winters are significantly milder and sunnier than those of the side that faces the Sea of Japan. Summers are hot because of the southeast seasonal wind. Precipitation is very heavy in the south and heavy in the summer in the north. The climate of the Ogasawara Island chain ranges from a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) to a tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw), with temperatures being warm to hot all year round.

- The climate of the Ryukyu Islands ranges from a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) in the north to a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south, with warm winters and hot summers. Precipitation is very high and is especially affected by the rainy season and typhoons.

Rainfall

[edit]Japan is generally a rainy country with high humidity.[27] Because of its wide range of latitude,[27] seasonal winds, and different types of ocean currents,[citation needed] Japan has a variety of climates, with the latitude range of the inhabited islands ranging from 24°N to 46°N, which is comparable to the range between Nova Scotia and The Bahamas on the east coast of North America.[27] Tokyo is between 35°N and 36°N, which is comparable to that of Tehran, Athens, or Las Vegas.[27]

As Mount Fuji and the coastal Japanese Alps provide a rain shadow, Nagano and Yamanashi Prefectures receive the least precipitation in Honshu, though it still exceeds 900 millimetres (35 in) annually. A similar effect is found in Hokkaido, where Okhotsk Subprefecture receives as little as 750 millimetres (30 in) per year. All other prefectures have coasts on the Pacific Ocean, Sea of Japan, or Seto Inland Sea or have a body of salt water connected to them. Two prefectures—Hokkaido and Okinawa—are composed entirely of islands.

Summer

[edit]The climate from June to September is marked by hot, wet weather brought by tropical airflows from the Pacific Ocean and Southeast Asia.[27] These air flows are full of moisture and deposit substantial amounts of rain when they reach land.[27] There is a marked rainy season, beginning in early June and continuing for about a month.[27] It is followed by hot, sticky weather.[27] Five or six typhoons pass over or near Japan every year from early August to early October, resulting in significant damage.[27] Annual precipitation averages between 1,000 and 2,500 mm (40 and 100 in) except for areas such as Kii Peninsula and Yakushima Island, which is Japan's wettest place,[110] with the annual precipitation being one of the world's highest at 4,000 to 10,000 mm.[111]

Maximum precipitation, like the rest of East Asia, occurs in the summer months except on the Sea of Japan coast, where strong northerly winds produce a maximum in late autumn and early winter. Except for a few sheltered inland valleys during December and January, precipitation in Japan is above 25 millimetres (1 in) of rainfall equivalent in all months of the year, and in the wettest coastal areas it is above 100 millimetres (4 in) per month throughout the year.

Mid-June to mid-July is generally the rainy season in Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, excluding Hokkaido since the seasonal rain front, or baiu zensen (梅雨前線), dissipates in northern Honshu before reaching Hokkaido. In Okinawa, the rainy season starts early in May and continues until mid-June. Unlike the rainy season in mainland Japan, it rains neither everyday nor all day long during the rainy season in Okinawa. Between July and October, typhoons, grown from tropical depressions generated near the equator, can attack Japan with furious rainstorms.

Winter

[edit]

In winter, the Siberian High develops over the Eurasian land mass and the Aleutian Low develops over the northern Pacific Ocean.[27] The result is a flow of cold air southeastward across Japan that brings freezing temperatures and heavy snowfalls to the central mountain ranges facing the Sea of Japan but clear skies to areas fronting the Pacific.[27]

The warmest winter temperatures are found in the Nanpō and Bonin Islands, which enjoy a tropical climate due to the combination of latitude, distance from the Asian continent, and warming effect of winds from the Kuroshio, as well as the Volcano Islands (at the latitude of the southernmost of the Ryukyu Islands, 24° N). The coolest summer temperatures are found on the northeastern coast of Hokkaido in Kushiro and Nemuro Subprefectures.

Sunshine

[edit]Sunshine, in accordance with Japan's uniformly heavy rainfall, is generally modest in quantity, though no part of Japan receives the consistently gloomy fogs that envelope the Sichuan Basin or Taipei. Amounts range from about six hours per day on the Inland Sea coast and sheltered parts of the Pacific Coast and Kantō Plain to four hours per day on the Sea of Japan coast of Hokkaido. In December, there is a very pronounced sunshine gradient between the Sea of Japan and Pacific coasts, as the former side can receive less than 30 hours and the Pacific side as much as 180 hours. In summer, however, sunshine hours are lowest on exposed parts of the Pacific coast, where fogs from the Oyashio current create persistent cloud cover similar to that found on the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin.

Extreme temperature records

[edit]The highest recorded temperature in Japan was 41.8 °C (107.2 °F) on 5 August 2025. An unverified record of 42.7 °C was taken in Adachi, Tokyo, on 20 July 2004. The high humidity and the maritime influence make temperatures in the 40s rare, with summers dominated by a more stable subtropical monsoon pattern through most of Japan. The lowest was −41.0 °C (−41.8 °F) in Asahikawa on 25 January 1902. However, an unofficial −41.5 °C was taken in Bifuka on 27 January 1931. Mount Fuji broke the Japanese record lows for each month except January, February, March, and December. Record lows for any month were taken as recently as 1984.

Minami-Tori-shima has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw) and the highest average temperature in Japan of 25 °C.[112]

| Climate data for Japan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.7 (85.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.7 (92.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

41.2 (106.2) |

41.8 (107.2) |

40.4 (104.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

34.2 (93.6) |

31.6 (88.9) |

41.8 (107.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −41.0 (−41.8) |

−38.3 (−36.9) |

−35.2 (−31.4) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−13.1 (8.4) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−34.2 (−29.6) |

−41.0 (−41.8) |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[113] and [114] | |||||||||||||

| Record high temperatures | Record low temperatures | ||||||||

| Month | °C | °F | Location | Date | °C | °F | Location | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 29.7 | 85.5 | Minami-Tori-shima | 7 January 1954 9 January 2021 |

−41.0 | −41.8 | Asahikawa, Hokkaido | 25 January 1902 | |

| February | 29.1 | 84.4 | Ishigaki | 16 February 1898 | −38.3 | −36.9 | Asahikawa, Hokkaido | 11 February 1902 | |

| March | 30.4 | 86.7 | Naze, Kagoshima | 26 March 1999 | −35.2 | −31.4 | Obihiro, Hokkaido | 3 March 1895 | |

| April | 33.7 | 92.7 | Yonago | 28 April 2005 | −27.8 | −18.0 | Mount Fuji | 3 April 1965 | |

| May | 39.5 | 103.1 | Saroma | 26 May 2019 | −18.9 | −2.0 | Mount Fuji | 3 May 1934 | |

| June | 40.2 | 104.4 | Isesaki | 25 June 2022 | −13.1 | 8.4 | Mount Fuji | 2 June 1981 | |

| July | 41.2 | 106.2 | Tamba | 30 July 2025 | −6.9 | 19.6 | Mount Fuji | 4 July 1966 | |

| August | 41.8 | 107.2 | Isesaki | 5 August 2025 | −4.3 | 24.3 | Mount Fuji | 25 August 1972 | |

| September | 40.4 | 104.7 | Sanjō, Niigata | 3 September 2020 | −10.8 | 12.6 | Mount Fuji | 23 September 1976 | |

| October | 36.0 | 96.8 | Sanjō, Niigata | 6 October 2018 | −19.5 | −3.2 | Mount Fuji | 30 October 1984 | |

| November | 34.2 | 94.4 | Minami-Tori-shima | 4 November 1953 | −28.1 | −18.6 | Mount Fuji | 30 November 1970 | |

| December | 31.6 | 88.9 | Minami-Tori-shima | 5 December 1952 | −34.2 | −29.6 | Obihiro, Hokkaido | 30 December 1907 | |

| Record high temperatures | Record low temperatures | ||||||||

| Season | °C | °F | Location | Date | °C | °F | Location | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | 31.6 | 88.9 | Minami-Tori-shima | 5 December 1952 | −41.0 | −41.8 | Asahikawa, Hokkaido | 25 January 1902 | |

| Spring | 39.5 | 103.1 | Saroma, Hokkaido | 26 May 2019 | −35.2 | −31.4 | Obihiro, Hokkaido | 3 March 1895 | |

| Summer | 41.1 | 106.0 | Kumagaya, Saitama Hamamatsu, Shizuoka |

23 July 2018 17 August 2020 |

−13.1 | 8.4 | Mount Fuji | 2 June 1981 | |

| Autumn | 40.4 | 104.7 | Sanjō, Niigata | 3 September 2020 | −28.1 | −18.6 | Mount Fuji | 30 November 1970 | |

Population distribution

[edit]

Japan has a population of 126.3 million in 2019.[20] It is the eleventh-most populous country and the second-most populous island country in the world.[12] The population is clustered in urban areas along the coast, plains, and valleys.[15] In 2010, 90.7% of the total Japanese population lived in cities.[115] Japan is an urban society, with about 5% of the labor force working in agriculture. About 80 million of the urban population is heavily concentrated on the Pacific coast of Honshu.[24]

81% of the population lives on Honshu, 10% on Kyushu, 4.2% on Hokkaido, 3% on Shikoku, 1.1% in Okinawa Prefecture, and 0.7% on other Japanese islands such as the Nanpō Islands. Nearly 1 in 3 Japanese people live in the Greater Tokyo Area, and over half live in the Kanto, Kinki, and Chukyo metropolitan areas.[116]

Honshu

[edit]Honshū (本州) is the largest island of Japan and the second most populous island in the world. It has a population of 104,000,000 with a population density of 450/km2 (1,200/sq mi) (2010).[117] Honshu is roughly 1,300 km (810 mi) long and ranges from 50 to 230 km (31 to 143 mi) wide, and the total area is 225,800 km2 (87,200 sq mi). It is the 7th largest island in the world.[118] This makes it slightly larger than the island of Great Britain (209,331 km2 (80,823 sq mi)).[118]

The Greater Tokyo Area on Honshu is the largest metropolitan area (megacity) in the world, with 38,140,000 people (2016).[119][120] The area is 13,500 km2 (5,200 sq mi)[121] and has a population density of 2,642 persons/km2.[122]

Kyushu

[edit]Kyushu (九州) is the third-largest island of Japan of the five main islands.[11][123] As of 2016[update], Kyushu has a population of 12,970,479 and covers 36,782 km2 (14,202 sq mi).[124] It has the second-highest population density of 307.13 persons/km2 (2016).

Shikoku

[edit]Shikoku (四国) is the second-smallest of the five main islands (after Okinawa Island), with 18,800 km2 (7,300 sq mi). It is located south of Honshu and northeast of Kyushu. It has the second-smallest population of 3,845,534 (2015)[11][125] and the third-highest population density of 204.55 persons/km2.

Hokkaido

[edit]Hokkaido (北海道) is the second-largest island of Japan and the largest and northernmost prefecture. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaido from Honshu.[126] It has the third largest population of the five main islands, with 5,383,579 (2015),[11][117] and the lowest population density, with just 64.5 persons/km2 (2016). The island area ranks 21st in the world by area. It is 3.6% smaller than the island of Ireland.

Okinawa Prefecture

[edit]Okinawa Prefecture (沖縄県) is the southernmost prefecture of Japan.[127] It encompasses two-thirds of the Ryukyu Islands, over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) long. It has a population of 1,445,812 (2017) and a density of 662 persons/km2. Okinawa Island (沖縄本島 or 沖縄島) is the smallest and most southwestern of the five main islands, at 1,206.98 km2 (466.02 sq mi).[11] It has the smallest population of 1,301,462 (2014) and the highest population density of 1083.6 persons/km2.

Nanpō Islands

[edit]Nanpō Islands (南方諸島) are the groups of islands that are located to the south and east of the main islands of the Japanese archipelago. They extend from the Izu Peninsula west of Tokyo Bay southward for about 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) to within 500 kilometres (310 mi) of the Mariana Islands. The Nanpō Islands are all administered by Tokyo Metropolis.

Taiheiyō Belt

[edit]

The Taiheiyō Belt is a megalopolis that includes the Greater Tokyo Area and Keihanshin megapoles. It is almost 1,200 km (750 mi) long, from Ibaraki Prefecture in the northeast to Fukuoka Prefecture in the southwest. Satellite images at night show a dense and continuous strip of light (demarcating urban zones) that delineates the region with overlapping metropolitan areas in Japan.[128] It has a total population of approximately 81,859,345 (2016).

- Taiheiyō Belt – includes Ibaraki, Saitama, Chiba, Tokyo, Kanagawa, Shizuoka, Aichi, Gifu, Mie, Kyoto, Osaka, Hyōgo, Wakayama, Okayama, Hiroshima, Yamaguchi, Fukuoka, and Ōita. (81,859,345 people)[129][130]

- Greater Tokyo Area – Part of the larger Kantō region, broadly includes Tokyo and Yokohama. (38,000,000 people)[131]

- Keihanshin – Part of the larger Kansai region, includes Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe. (19,341,976 people)[132]

Underwater habitats

[edit]There are plans to build underwater habitats in Japan's Exclusive Economic Zone. Currently no underwater city is constructed yet. For example, the Ocean Spiral by Shimizu Corporation would have a floating dome 500 meters in diameter with hotels, residential and commercial complexes. It could be 15 km long. This allows mining of the seabed, research and production of methane from carbon dioxide with micro-organisms. The Ocean Spiral was co-developed with JAMSTEC and Tokyo University.[133][134]

Extreme points

[edit]

Japan extends from 20° to 45° north latitude (Okinotorishima to Benten-jima) and from 122° to 153° east longitude (Yonaguni to Minami Torishima).[19] These are the points that are farther north, south, east, or west than any other location in Japan.

| Heading | Location | Prefecture | Bordering entity | Coordinates† | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North (disputed) |

Cape Kamoiwakka on Etorofu | Hokkaido‡ | Sea of Okhotsk | 45°33′26″N 148°45′09″E / 45.55722°N 148.75250°E | [135] |

| North (undisputed) |

Benten-jima | Hokkaido | La Pérouse Strait | 45°31′38″N 141°55′06″E / 45.52722°N 141.91833°E | [136] |

| South | Okinotorishima | Tokyo | Philippine Sea | 20°25′31″N 136°04′11″E / 20.42528°N 136.06972°E | |

| East | Minami Torishima | Tokyo | Pacific Ocean | 24°16′59″N 153°59′11″E / 24.28306°N 153.98639°E | |

| West | Yonaguni | Okinawa | East China Sea | 24°26′58″N 122°56′01″E / 24.44944°N 122.93361°E | The westernmost Monument of Japan |

Japan's main islands

[edit]The five main islands of Japan are Hokkaido, Honshū, Kyūshū, Shikoku, and Okinawa. These are also called the mainland.[11] All of these points are accessible to the public.

| Heading | Location | Prefecture | Bordering entity | Coordinates† | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Cape Sōya | Hokkaido | La Pérouse Strait | 45°31′22″N 141°56′11″E / 45.52278°N 141.93639°E | |

| South | Cape Arasaki | Okinawa | East China Sea | 26°04′30″N 127°40′51″E / 26.07500°N 127.68083°E | |

| East | Cape Nosappu | Hokkaido | Pacific Ocean | 43°23′06″N 145°49′03″E / 43.38500°N 145.81750°E | |

| West | Cape Oominezaki | Okinawa | East China Sea | 26°11′55″N 127°38′11″E / 26.19861°N 127.63639°E |

Extreme altitudes

[edit]| Extremity | Name | Altitude | Prefecture | Coordinates† | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest | Mount Fuji | 3,776 m (12,388 ft) | Yamanashi | 35°21′29″N 138°43′52″E / 35.35806°N 138.73111°E | [3] |

| Lowest (human-made) |

Hachinohe mine | −170 m (−558 ft) | Aomori | 40°27′10″N 141°32′16″E / 40.45278°N 141.53778°E | [137] |

| Lowest (natural) |

Hachirōgata | −4 m (−13 ft) | Akita | 39°54′50″N 140°01′15″E / 39.91389°N 140.02083°E | [3] |

Largest islands of Japan

[edit]

These are the 50 largest islands of Japan. It excludes the disputed Kuril Islands, known as the northern territories.

| Rank | Island name | Area (km2) |

Area (sq mi) |

Island group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Honshu | 227,960 | 88,020 | |

| 2 | Hokkaido | 83,424.31 | 32,210.31 | |

| 3 | Kyushu | 36,782 | 14,202 | |

| 4 | Shikoku | 18,800 | 7,300 | |

| 5 | Okinawa Island | 1,207 | 466 | Ryukyu Islands |

| 6 | Sado Island | 855.26 | 330.22 | |

| 7 | Amami Ōshima | 712.35 | 275.04 | Amami Islands |

| 8 | Tsushima Island | 708.7 | 273.6 | |

| 9 | Awaji Island | 592.17 | 228.64 | |

| 10 | Shimoshima Island, Amakusa | 574.01 | 221.63 | |

| 11 | Yakushima | 504.88 | 194.94 | Ōsumi Islands |

| 12 | Tanegashima | 444.99 | 171.81 | Ōsumi Islands |

| 13 | Fukue Island | 326.43 | 126.04 | Gotō Islands |

| 14 | Iriomote Island | 289.27 | 111.69 | |

| 15 | Tokunoshima | 247.8 | 95.7 | |

| 16 | Dōgojima | 241.58 | 93.27 | Oki Islands |

| 17 | Kamishima Island, Amakusa | 225.32 | 87.00 | Amakusa islands |

| 18 | Ishigaki Island | 222.5 | 85.9 | |

| 19 | Rishiri Island | 183 | 71 | |

| 20 | Nakadōri Island | 168.34 | 65.00 | Gotō Islands |

| 21 | Hirado Island | 163.42 | 63.10 | |

| 22 | Miyako-jima | 158.87 | 61.34 | |

| 23 | Shōdoshima | 153.30 | 59.19 | |

| 24 | Okushiri Island | 142.97 | 55.20 | |

| 25 | Iki Island | 138.46 | 53.46 | |

| 26 | Suō-Ōshima | 128.31 | 49.54 | |

| 27 | Okinoerabujima | 93.63 | 36.15 | |

| 28 | Etajima | 91.32 | 35.26 | |

| 29 | Izu Ōshima | 91.06 | 35.16 | Izu Islands |

| 30 | Nagashima Island, Kagoshima | 90.62 | 34.99 | |

| 31 | Rebun Island | 80 | 31 | |

| 32 | Kakeromajima | 77.39 | 29.88 | |

| 33 | Kurahashi-jima | 69.46 | 26.82 | |

| 34 | Shimokoshiki-jima | 66.12 | 25.53 | |

| 35 | Ōmishima Island, Ehime | 66.12 | 25.53 | |

| 36 | Hachijō-jima | 62.52 | 24.14 | |

| 37 | Kume Island | 59.11 | 22.82 | Okinawa Islands |

| 38 | Kikaijima | 56.93 | 21.98 | Amami Islands |

| 39 | Nishinoshima | 55.98 | 21.61 | |

| 40 | Miyake-jima | 55.44 | 21.41 | |

| 41 | Notojima | 46.78 | 18.06 | |

| 42 | Kamikoshiki-jima | 45.08 | 17.41 | |

| 43 | Ōshima (Ehime) | 41.87 | 16.17 | |

| 44 | Ōsakikamijima | 38.27 | 14.78 | |

| 45 | Kuchinoerabu-jima | 38.04 | 14.69 | |

| 46 | Hisaka | 37.23 | 14.37 | |

| 47 | Innoshima | 35.03 | 13.53 | |

| 48 | Nakanoshima (in Kagoshima) | 34.47 | 13.31 | Tokara Islands |

| 49 | Hario Island | 33.16 | 12.80 | |

| 50 | Nakanoshima (in Shimane) | 32.21 | 12.44 | Oki Islands |

Northern Territories

[edit]

Japan has a longstanding claim to the Southern Kuril Islands (Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan, and the Habomai Islands). These islands were occupied by the Soviet Union in 1945.[138] The Kuril Islands historically belonged to Japan.[139] The Kuril Islands were first inhabited by the Ainu people and then controlled by the Japanese Matsumae clan in the Edo Period.[140] The Soviet Union did not sign the San Francisco Treaty in 1951. The U.S. Senate Resolution of April 28, 1952, ratifying the San Francisco Treaty, explicitly stated that the USSR had no title to the Kurils.[141] This dispute has prevented the signing of a peace treaty between Japan and Russia.

Geographically, the Kuril Islands are a northeastern extension of Hokkaido. Kunashiri and the Habomai Islands are visible from the northeastern coast of Hokkaido. Japan considers the northern territories (aka Southern Chishima) part of the Nemuro Subprefecture of Hokkaido Prefecture.

Time zone

[edit]There is one time zone in the whole Japanese archipelago. It is 9 hours ahead of UTC.[142] There is no daylight saving time. The easternmost Japanese island, Minami-Tori-shima, also uses Japan Standard Time, while it is geographically 1,848 kilometres (1,148 mi) southeast of Tokyo and in the UTC+10:00 time zone.

Sakhalin uses UTC+11:00, even though it is located directly north of Hokkaido. The Northern Territories and the Kuril Islands use UTC+11:00, although they are geographically in UTC+10:00.

Natural hazards

[edit]Earthquakes and tsunami

[edit]

Japan is substantially prone to earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanoes because of its location along the Pacific Ring of Fire.[143] It has the 15th highest natural disaster risk as measured in the 2013 World Risk Index.[144]

As many as 1,500 earthquakes are recorded yearly, and magnitudes of 4 to 6 are common.[27] Minor tremors occur almost daily in one part of the country or another, causing slight shaking of buildings.[27] Undersea earthquakes also expose the Japanese coastline to danger from tsunamis (津波).[27]

Destructive earthquakes, often resulting in tsunamis, occur several times each century.[18] The 1923 Tokyo earthquake killed over 140,000 people.[145] More recent major quakes are the 1995 Great Hanshin earthquake and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, a 9.1-magnitude[146] quake that hit Japan on March 11, 2011. It triggered a large tsunami and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, one of the worst disasters in the history of nuclear power.[147]

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake was the largest ever recorded in Japan and is the world's fourth largest earthquake to strike since 1900, according to the U.S. Geological Service. It struck offshore about 371 kilometres (231 mi) northeast of Tokyo and 130 kilometres (81 mi) east of the city of Sendai and created a massive tsunami that devastated Japan's northeastern coastal areas. At least 100 aftershocks registering a magnitude of 6.0 or higher have followed the main shock. At least 15,000 people died as a result.

Researchers found the source of great thrust earthquakes and associated tsunamis in the Greater Tokyo Area at the Izu-Ogasawara Trench.[148] There is a 'trench-trench triple junction' of the oceanic Philippine Sea Plate that underthrusts a continental plate and is being subducted by the Pacific Plate.[148]

Reclaimed land and human-made islands are particularly susceptible to liquefaction during an earthquake. As a result, there are specific earthquake resistance standards and ground reform work that apply to all construction in these areas. In an area that was possibly reclaimed in the past, old maps and land condition drawings are checked, and drilling is carried out to determine the strength of the ground. However, this can be very costly, so for a private residential block of land, a Swedish weight sounding test is more common.[38]

Japan has become a world leader in research on the causes and prediction of earthquakes.[27] The development of advanced technology has permitted the construction of skyscrapers even in earthquake-prone areas.[27] Extensive civil defense efforts focus on training in protection against earthquakes, in particular against accompanying fire, which represents the greatest danger.[27]

Volcanic eruptions

[edit]

Japan has 111 active volcanoes. That is 10% of all active volcanoes in the world. Japan has stratovolcanoes near the subduction zones of the tectonic plates. During the 20th century, several new volcanoes emerged, including Shōwa-shinzan on Hokkaido and Myōjin-shō off the Bayonnaise Rocks in the Pacific.[18] In 1991, Japan's Unzen Volcano on Kyushu, about 40 km (25 mi) east of Nagasaki, awakened from its 200-year slumber to produce a new lava dome at its summit. Beginning in June, repeated collapse of this erupting dome generated ash flows that swept down the mountain's slopes at speeds as high as 200 km/h (120 mph). Unzen erupted in 1792 and killed more than 15,000 people. It is the worst volcanic disaster in the country's recorded history.[149]

Mount Fuji is a dormant stratovolcano that last erupted on 16 December 1707 till about 1 January 1708.[150][151] The Hōei eruption of Mount Fuji did not have a lava flow, but it did release some 800 million cubic metres (28×109 cu ft) of volcanic ash. It spread over vast areas around the volcano and reached Edo almost 100 kilometres (60 mi) away. Cinders and ash fell like rain in Izu, Kai, Sagami, and Musashi provinces.[152] In Edo, the volcanic ash was several centimeters thick.[153] The eruption is rated a 5 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index.[154]

There are three VEI-7 volcanoes in Japan. These are the Aira Caldera, the Kikai Caldera, and the Aso Caldera. These giant calderas are remnants of past eruptions. Mount Aso is the largest active volcano in Japan. 300,000 to 90,000 years ago, there were four eruptions of Mount Aso that emitted huge amounts of volcanic ash that covered all of Kyushu and up to Yamaguchi Prefecture.

- The Aira Caldera is 17 kilometers long and 23 kilometers wide, located in south Kyushu. The city of Kagoshima and the Sakurajima volcano are within the Aira Caldera. Sakurajima is the most active volcano in Japan.[155]

- The Aso Caldera stretches 25 kilometers north to south and 18 kilometers east to west in Kumamoto Prefecture, Kyushu. It has erupted four times: 266,000 and 141,000 years ago with 32 DRE km3 (dense-rock equivalent) each; 130,000 years ago with 96 DRE km3; and 90,000 years ago with 384 DRE km3.[156]

- The Kikai Caldera is a massive, mostly submerged caldera up to 19 kilometres (12 mi) in diameter in the Ōsumi Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. It is the remains of the ancient eruption of a colossal volcano. Kikai Caldera was the source of the Akahoya eruption, one of the largest eruptions during the Holocene (10,000 years ago to present). About 4,300 BC, pyroclastic flows from that eruption reached the coast of southern Kyūshū up to 100 km (62 mi) away, and ash fell as far as Hokkaido. The eruption produced about 150 km3 of tephra,[157] giving it a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 7.[158] The Jōmon culture of at least southern Kyushu was destroyed, and it took nearly 1,000 years to recover.[159]

Surveys by KOBEC (Kobe Ocean-Bottom Exploration Center) confirm that a giant lava dome of 23 cubic kilometers formed after the Kikai Caldera erupted in 4,300 BC. There is a 1% chance of a giant caldera eruption in the Japanese archipelago within the next 100 years. Approximately 40 cubic kilometers of magma would be released in one burst and cause enormous damage.[160]

According to a 2014 study by KOBEC of Kobe University, in a worst-case scenario, if there is a VEI-7 eruption of the Aso Caldera and if the volcanic ash is carried by westerly winds, then pyroclastic flows would cover the 7 million population near the Aso Caldera within two hours. The pyroclastic flows could reach much of Kyushu. Beyond the pyroclastic area is volcanic ash that falls from the sky. If the volcanic ash continuously flows northward, then the ash fall would make it impossible to live normally in large parts of the main islands of Japan due to the paralysis of traffic and lifelines for a limited period (a few days to 2 weeks) until the eruption subsides. In this scenario, the exception would be eastern and northern Hokkaido (the Ryukyu Islands and southern Nanpo Islands would also be excluded). Professor Yoshiyuki Tatsumi, head of KOBEC, told the Mainichi Shimbun that "the probability of a gigantic caldera eruption hitting the Japanese archipelago is 1 percent in the next 100 years" with a death toll of many tens of millions of people and wildlife.[159] The potential exists for tens of millions of humans and other living beings to die during a VEI-7 volcanic eruption with significant short-term effects on the global climate. Most casualties would occur in Kyushu from the pyroclastic flows. The potential damage from the volcanic ash depends on the wind direction. If, in another scenario, the wind blows in a western or southern direction, then the volcanic ash could affect the East Asian continent or South-East Asia. If the ash flows eastward, then it will spread over the Pacific Ocean. Since the Kikai Caldera is submerged, it is unclear how much damage the hot ash clouds would cause if large quantities of volcanic ash stayed beneath the ocean surface. The underwater ash would be swept away by ocean currents.

Paektu Mountain on the Chinese–North Korean border had a VEI-7 eruption in 946. Paektu Mountain is mainly a threat to the surrounding area in North Korea and Manchuria. The west coast of Hokkaido is about 971.62 km (603.74 mi) away. However, a temple in Japan reported "white ash falling like snow" on 3 November 946 AD.[161] So strong winds carried the volcanic ash eastward across the Sea of Japan. An average of 5 cm (2.0 in) of ashfall covered about 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi) of the Sea of Japan and northern Japan (Hokkaido and Aomori Prefecture).[162] It took the ash clouds a day or so to reach Hokkaido.[161] The total eruption duration was 4 and a half to 14 days (111–333 hours).[163]

In October 2021, large quantities of pumice pebbles from the submarine volcano Fukutoku-Okanoba damaged fisheries, tourism, the environment, 11 ports in Okinawa, and 19 ports in Kagoshima prefecture.[164] Clean-up operations took 2–3 weeks.[164]

| Name | Zone | Location | Event / notes | Years ago before 1950 (Approx.) | Ejecta volume (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kikai Caldera | Japan, Ryukyu Islands | Akahoya eruption 5,300 BC | 7,300[165] | 170 km3 | |

| Aira Caldera | Japan, Kyūshū | Aira-Tanzawa ash | 30,000[165] | 450 km3 | |

| Aso Caldera | Japan, Kyūshū | Aso-4 pyroclastic flow | 90,000 | 600 km3 | |

| Mount Aso | Japan, Kyūshū | Four large eruptions between 300,000 and 90,000 years ago. | 300,000 | 600 km3 |

Improving technology and methods to predict volcano and giant caldera eruptions would help to prepare and evacuate people earlier. Technology is needed to accurately capture the state of the magma chamber, which spreads thinly with a thickness of less than several kilometers around the middle of the crust. The underground area of Kyushu must be monitored because it is a dangerous area with the potential for a caldera eruption. The most protective measure is to stop the hot ash clouds from spreading and devastating areas near the eruption so that people don't need to evacuate. There are currently no protective measures to minimize the spread of millions of tons of deadly hot ash during a VEI-7 eruption.

In 2018, NASA published a theoretical plan to prevent a volcanic eruption by pumping large quantities of cold water down a borehole into the hydrothermal system of a supervolcano. The water would cool the huge body of magma in the chambers below the volcano so that the liquid magma would become semi-solid. Thus, enough heat could be extracted to prevent an eruption. The heat could be used by a geothermal plant to generate geothermal energy and electricity.[166]

Typhoons

[edit]Since recording started in 1951, an average of 2.6 typhoons reached the main islands of Kyushu, Shikoku, Honshu, and Hokkaido per year. Approximately 10.3 typhoons approach within the 300-kilometer range near the coast of Japan. Okinawa is, due to its geographic location, most vulnerable to typhoons, with an average of 7 storms per year. The most destructive was the Isewan Typhoon, with 5,000 casualties in the Tokai region in September 1959. In October 2004, Typhoon Tokage caused heavy rain in Kyushu and central Japan, resulting in 98 casualties. Until the 1960s, the death toll was hundreds of people per typhoon. Since the 1960s, improvements in construction, flood prevention, high tide detection, and early warnings have substantially reduced the death toll, which rarely exceeds a dozen people per typhoon. Japan also has special search and rescue units to save people in distress.

Heavy snowfall during the winter in the snow country regions causes landslides, flooding, and avalanches.

Environmental issues

[edit]In the 2006 environment annual report,[167] the Ministry of Environment reported that the current major issues are: global warming and preservation of the ozone layer; conservation of the atmospheric environment, water, and soil; waste management and recycling; measures for chemical substances; conservation of the natural environment; and participation in international cooperation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Countries ranked by Surface area (Sq. Km)". Archived from the original on 2021-10-11. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ a b c d "【お知らせ】令和3年全国都道府県市区町村別面積調(7月1日時点), Reiwa 3rd year National area of each prefecture municipality (as of July 1)" (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. 23 March 2022. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Japan". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Shinano River". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Lake Biwa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2017.