Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cis–trans isomerism

View on Wikipedia

Cis–trans isomerism, also known as geometric isomerism, describes certain arrangements of atoms within molecules. The prefixes "cis" and "trans" are from Latin: "this side of" and "the other side of", respectively.[1] In the context of chemistry, cis indicates that the functional groups (substituents) are on the same side of some plane, while trans conveys that they are on opposing (transverse) sides. Cis–trans isomers are stereoisomers, that is, pairs of molecules which have the same formula but whose functional groups are in different orientations in three-dimensional space. Cis and trans isomers occur both in organic molecules and in inorganic coordination complexes. Cis and trans descriptors are not used for cases of conformational isomerism where the two geometric forms easily interconvert, such as most open-chain single-bonded structures; instead, the terms "syn" and "anti" are used.

According to IUPAC, "geometric isomerism" is an obsolete synonym of "cis–trans isomerism".[2]

Cis–trans or geometric isomerism is classified as one type of configurational isomerism.[3]

Organic chemistry

[edit]Very often, cis–trans stereoisomers contain double bonds or ring structures. In both cases the rotation of bonds is restricted or prevented.[4] When the substituent groups are oriented in the same direction, the diastereomer is referred to as cis, whereas when the substituents are oriented in opposing directions, the diastereomer is referred to as trans. An example of a small hydrocarbon displaying cis–trans isomerism is but-2-ene. 1,2-Dichlorocyclohexane is another example.

|

|

| trans-1,2-dichlorocyclohexane | cis-1,2-dichlorocyclohexane |

Comparison of physical properties

[edit]Cis and trans isomers have distinct physical properties. Their differing shapes influences the dipole moments, boiling, and especially melting points.

|

|

| cis-2-pentene | trans-2-pentene |

|

|

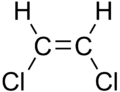

| cis-1,2-dichloroethene | trans-1,2-dichloroethene |

These differences can be very small, as in the case of the boiling point of straight-chain alkenes, such as pent-2-ene, which is 37 °C in the cis isomer and 36 °C in the trans isomer.[5] The differences between cis and trans isomers can be larger if polar bonds are present, as in the 1,2-dichloroethenes. The cis isomer in this case has a boiling point of 60.3 °C, while the trans isomer has a boiling point of 47.5 °C.[6] In the cis isomer the two polar C–Cl bond dipole moments combine to give an overall molecular dipole, so that there are intermolecular dipole–dipole forces (or Keesom forces), which add to the London dispersion forces and raise the boiling point. In the trans isomer on the other hand, this does not occur because the two C−Cl bond moments cancel and the molecule has a net zero dipole moment (it does however have a non-zero quadrupole moment).

|

|

| cis-butenedioic acid (maleic acid) |

trans-butenedioic acid (fumaric acid) |

|

|

| cis-9-octadecenoic acid (oleic acid) |

trans-9-octadecenoic acid (elaidic acid) |

The differing properties of the two isomers of butenedioic acid are often very different.

| maleic acid | fumaric acid | |

|---|---|---|

| color | white | white |

| melting point, °C | 130 | 286 |

| water solubility, g/L | 788 | 7 |

| Acid dissociation constant, pKa1 | 1.90 | 3.03 |

Polarity is key in determining relative boiling point as strong intermolecular forces raise the boiling point. In the same manner, symmetry is key in determining relative melting point as it allows for better packing in the solid state, even if it does not alter the polarity of the molecule. Another example of this is the relationship between oleic acid and elaidic acid; oleic acid, the cis isomer, has a melting point of 13.4 °C, making it a liquid at room temperature, while the trans isomer, elaidic acid, has the much higher melting point of 43 °C, due to the straighter trans isomer being able to pack more tightly, and is solid at room temperature.

Thus, trans alkenes, which are less polar and more symmetrical, have lower boiling points and higher melting points, and cis alkenes, which are generally more polar and less symmetrical, have higher boiling points and lower melting points.

In the case of geometric isomers that are a consequence of double bonds, and, in particular, when both substituents are the same, some general trends usually hold. These trends can be attributed to the fact that the dipoles of the substituents in a cis isomer will add up to give an overall molecular dipole. In a trans isomer, the dipoles of the substituents will cancel out [7] due to being on opposite sides of the molecule. Trans isomers also tend to have lower densities than their cis counterparts.[citation needed]

As a general trend, trans alkenes tend to have higher melting points and lower solubility in inert solvents, as trans alkenes, in general, are more symmetrical than cis alkenes.[8]

Vicinal coupling constants (3JHH), measured by NMR spectroscopy, are larger for trans (range: 12–18 Hz; typical: 15 Hz) than for cis (range: 0–12 Hz; typical: 8 Hz) isomers.[9]

Stability

[edit]Usually for acyclic systems trans isomers are more stable than cis isomers. This difference is attributed to the unfavorable steric interaction of the substituents in the cis isomer. Therefore, trans isomers have a less-exothermic heat of combustion, indicating higher thermochemical stability.[8] In the Benson heat of formation group additivity dataset, cis isomers suffer a 1.10 kcal/mol stability penalty. Exceptions to this rule exist, such as 1,2-difluoroethylene, 1,2-difluorodiazene (FN=NF), and several other halogen- and oxygen-substituted ethylenes. In these cases, the cis isomer is more stable than the trans isomer.[10] This phenomenon is called the cis effect.[11]

E–Z notation

[edit]

In principle, cis–trans notation should not be used for alkenes with two or more different substituents. Instead the E–Z notation is used based on the priority of the substituents using the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog (CIP) priority rules for absolute configuration. The IUPAC standard designations E and Z are unambiguous in all cases, and therefore are especially useful for tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes to avoid any confusion about which groups are being identified as cis or trans to each other.

Z (from the German zusammen) means "together". E (from the German entgegen) means "opposed" in the sense of "opposite". That is, Z has the higher-priority groups cis to each other and E has the higher-priority groups trans to each other. Whether a molecular configuration is designated E or Z is determined by the CIP rules; higher atomic numbers are given higher priority. For each of the two atoms in the double bond, it is necessary to determine the priority of each substituent. If both the higher-priority substituents are on the same side, the arrangement is Z; if on opposite sides, the arrangement is E.

Because the cis–trans and E–Z systems compare different groups on the alkene, it is not strictly true that Z corresponds to cis and E corresponds to trans. For example, trans-2-chlorobut-2-ene (the two methyl groups, C1 and C4, on the but-2-ene backbone are trans to each other) is (Z)-2-chlorobut-2-ene (the chlorine and C4 are together because C1 and C4 are opposite).

Undefined alkene stereochemistry

[edit]Wavy single bonds are the standard way to represent unknown or unspecified stereochemistry or a mixture of isomers (as with tetrahedral stereocenters). A crossed double-bond has been used sometimes; it is no longer considered an acceptable style for general use by IUPAC but may still be required by computer software.[12]

Inorganic chemistry

[edit]Cis–trans isomerism can also occur in inorganic compounds.

Diazenes

[edit]Diazenes (and the related diphosphenes) can also exhibit cis–trans isomerism. As with organic compounds, the cis isomer is generally the more reactive of the two, being the only isomer that can reduce alkenes and alkynes to alkanes, but for a different reason: the trans isomer cannot line its hydrogens up suitably to reduce the alkene, but the cis isomer, being shaped differently, can.

|

|

| trans-diazene | cis-diazene |

Coordination complexes

[edit]Coordination complexes with octahedral or square planar geometries can also exhibit cis-trans isomerism.

For example, there are two isomers of square planar Pt(NH3)2Cl2, as explained by Alfred Werner in 1893. The cis isomer, whose full name is cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II), was shown in 1969 by Barnett Rosenberg to have antitumor activity, and is now a chemotherapy drug known by the short name cisplatin. In contrast, the trans isomer (transplatin) has no useful anticancer activity. Each isomer can be synthesized using the trans effect to control which isomer is produced.

For octahedral complexes of formula MX4Y2, two isomers also exist. (Here M is a metal atom, and X and Y are two different types of ligands.) In the cis isomer, the two Y ligands are adjacent to each other at 90°, as is true for the two chlorine atoms shown in green in cis-[Co(NH3)4Cl2]+, at left. In the trans isomer shown at right, the two Cl atoms are on opposite sides of the central Co atom.

A related type of isomerism in octahedral MX3Y3 complexes is facial–meridional (or fac–mer) isomerism, in which different numbers of ligands are cis or trans to each other. Metal carbonyl compounds can be characterized as fac or mer using infrared spectroscopy.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary (Clarendon Press, 1879) Entry for cis

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "geometric isomerism". doi:10.1351/goldbook.G02620

- ^ Hunt, Ian. "Stereochemistry". University of Calgary. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ Reusch, William (2010). "Stereoisomers Part I". Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry. Michigan State University. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Chemicalland values". Chemicalland21.com. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (60th ed.). 1979–1980. p. C-298.

- ^ Ouellette, Robert J.; Rawn, J. David (2015). "Alkenes and Alkynes". Principles of Organic Chemistry. pp. 95–132. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802444-7.00004-5. ISBN 978-0-12-802444-7.

- ^ a b March, Jerry (1985). Advanced Organic Chemistry, Reactions, Mechanisms and structure (3rd ed.). p. 111. ISBN 978-0-471-85472-2.

- ^ Williams, Dudley H.; Fleming, Ian (1989). "Table 3.27". Spectroscopic Methods in Organic Chemistry (4th rev. ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-707212-4.

- ^ Bingham, Richard C. (1976). "The stereochemical consequences of electron delocalization in extended π systems. An interpretation of the cis effect exhibited by 1,2-disubstituted ethylenes and related phenomena". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98 (2): 535–540. doi:10.1021/ja00418a036.

- ^ Craig, N. C.; Chen, A.; Suh, K. H.; Klee, S.; Mellau, G. C.; Winnewisser, B. P.; Winnewisser, M. (1997). "Contribution to the Study of the Gauche Effect. The Complete Structure of the Anti Rotamer of 1,2-Difluoroethane". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (20): 4789. doi:10.1021/ja963819e.

- ^ Brecher, Jonathan (2006). "Graphical representation of stereochemical configuration (IUPAC Recommendations 2006)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 78 (10): 1897–1970. doi:10.1351/pac200678101897. S2CID 97528124.

External links

[edit]Cis–trans isomerism

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and principles

Cis–trans isomerism, also known as geometric isomerism, refers to a type of stereoisomerism in which molecules have the same molecular formula and connectivity of atoms but differ in the spatial arrangement of substituents due to restricted rotation around certain bonds.[7] This form of isomerism typically arises in compounds featuring carbon-carbon double bonds, where each carbon of the double bond bears two different substituents, or in cyclic structures, where the rigidity prevents free rotation, leading to distinct cis and trans configurations.[8] In the cis isomer, the substituents of interest are located on the same side of the bond or plane, whereas in the trans isomer, they are on opposite sides.[3] The underlying principle is the restricted rotation caused by the pi bond in a carbon-carbon double bond (C=C), which overlaps sideways between the p orbitals of the adjacent carbons, creating a barrier to rotation that requires breaking the pi bond to overcome.[7] Similarly, in cyclic compounds, the ring structure imposes geometric constraints that limit substituent positions, mimicking the effect of restricted rotation.[9] These cis and trans isomers are configurational stereoisomers, meaning interconversion between them necessitates breaking and reforming bonds, unlike conformational isomers that can interconvert by rotation around single bonds.[7] A classic example is 2-butene (C₄H₈), where the double bond between the second and third carbon atoms allows for cis and trans forms. In cis-2-butene, the two methyl groups (–CH₃) are on the same side of the double bond, resulting in a structure where the molecule is more compact; in trans-2-butene, the methyl groups are on opposite sides, leading to a more extended arrangement. These can be represented as: For cis-2-butene:CH₃–CH=CH–CH₃ (methyl groups same side) For trans-2-butene:

CH₃–CH=CH–CH₃ (methyl groups opposite sides) This isomerism was first systematically described in 1874 by Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff in his work La Chimie dans l'Espace, where he introduced the concepts of spatial arrangements around double bonds and rings as part of the foundational development of stereochemistry.[10]