Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Steroid

View on Wikipedia

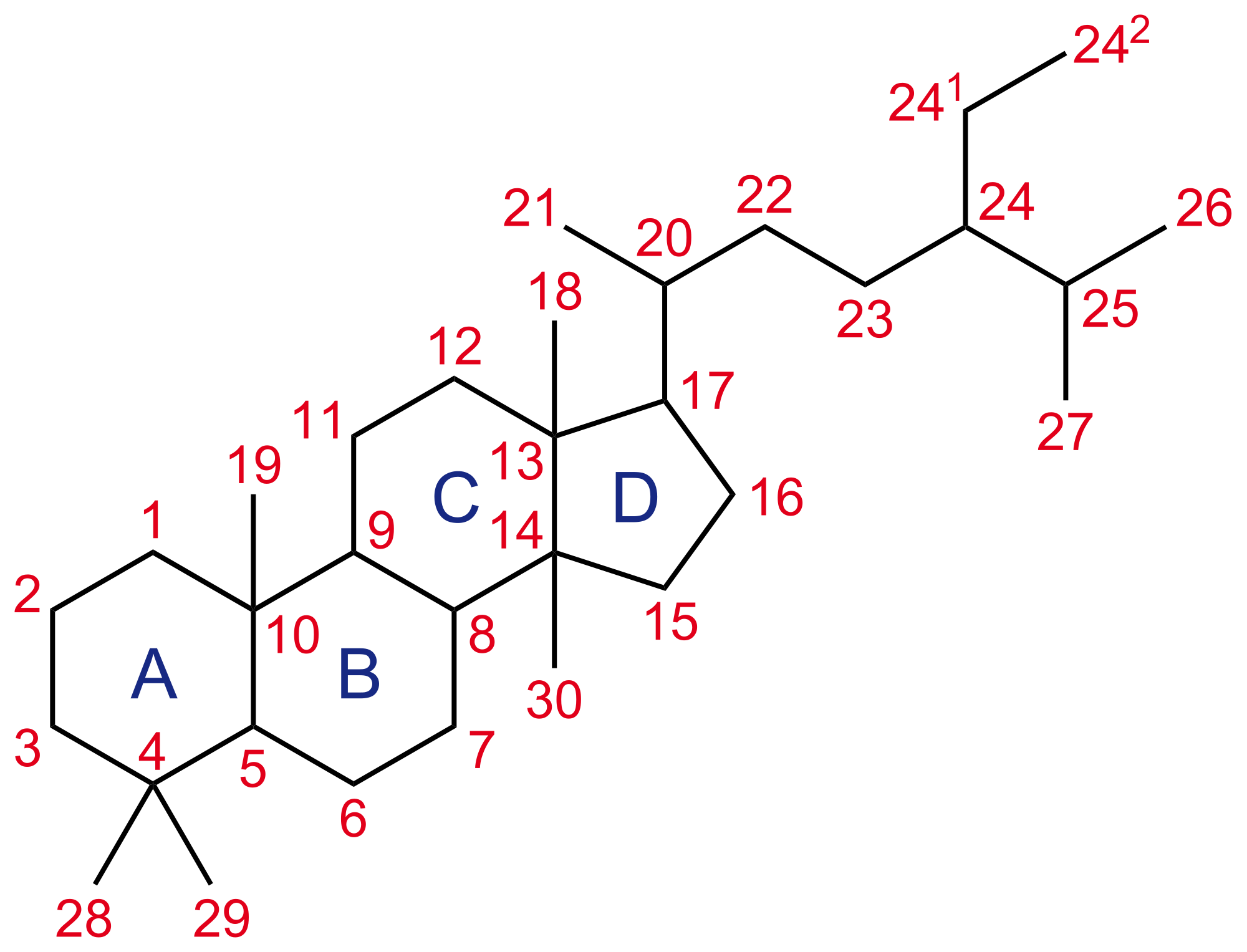

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused rings (designated A, B, C, and D) arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and as signaling molecules. Examples include the lipid cholesterol, sex hormones estradiol and testosterone,[2]: 10–19 anabolic steroids, and the anti-inflammatory corticosteroid drug dexamethasone.[3] Hundreds of steroids are found in fungi, plants, and animals. All steroids are manufactured in cells from a sterol: cholesterol (animals), lanosterol (opisthokonts), or cycloartenol (plants). All three of these molecules are produced via cyclization of the triterpene squalene.[4]

Structure

[edit]The steroid nucleus (core structure) is called gonane (cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene).[5] It is typically composed of seventeen carbon atoms, bonded in four fused rings: three six-member cyclohexane rings (rings A, B and C in the first illustration) and one five-member cyclopentane ring (the D ring). Steroids vary by the functional groups attached to this four-ring core and by the oxidation state of the rings. Sterols are forms of steroids with a hydroxy group at position three and a skeleton derived from cholestane.[1]: 1785f [6] Steroids can also be more radically modified, such as by changes to the ring structure, for example, cutting one of the rings. Cutting Ring B produces secosteroids one of which is vitamin D3.

Nomenclature

[edit]Rings and functional groups

[edit]

Steroids are named after the steroid cholesterol[7] which was first described in gall stones from Ancient Greek chole- 'bile' and stereos 'solid'.[8][9][10]

Gonane, also known as steran or cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene, the nucleus of all steroids and sterols,[11][12] is composed of seventeen carbon atoms in carbon-carbon bonds forming four fused rings in a three-dimensional shape. The three cyclohexane rings (A, B, and C in the first illustration) form the skeleton of a perhydro derivative of phenanthrene. The D ring has a cyclopentane structure. When the two methyl groups and eight carbon side chains (at C-17, as shown for cholesterol) are present, the steroid is said to have a cholestane framework. The two common 5α and 5β stereoisomeric forms of steroids exist because of differences in the side of the largely planar ring system where the hydrogen (H) atom at carbon-5 is attached, which results in a change in steroid A-ring conformation. Isomerisation at the C-21 side chain produces a parallel series of compounds, referred to as isosteroids.[13]

Examples of steroid structures are:

-

Dexamethasone, a synthetic corticosteroid drug

-

Lanosterol, the biosynthetic precursor to animal steroids. The number of carbons (30) indicates its triterpenoid classification.

-

Progesterone, a steroid hormone involved in the female menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and embryogenesis

-

Medrogestone, a synthetic drug with effects similar to progesterone

-

β-Sitosterol, a plant or phytosterol, with a fully branched hydrocarbon side chain at C-17 and an hydroxyl group at C-3

In addition to the ring scissions (cleavages), expansions and contractions (cleavage and reclosing to a larger or smaller rings)—all variations in the carbon-carbon bond framework—steroids can also vary:

- in the bond orders within the rings,

- in the number of methyl groups attached to the ring (and, when present, on the prominent side chain at C17),

- in the functional groups attached to the rings and side chain, and

- in the configuration of groups attached to the rings and chain.[2]: 2–9

For instance, sterols such as cholesterol and lanosterol have a hydroxyl group attached at position C-3, while testosterone and progesterone have a carbonyl (oxo substituent) at C-3. Among these compounds, only lanosterol has two methyl groups at C-4. Cholesterol which has a C-5 to C-6 double bond, differs from testosterone and progesterone which have a C-4 to C-5 double bond.

|

|

Naming convention

[edit]Almost all biologically relevant steroids can be presented as a derivative of a parent cholesterol-like hydrocarbon structure that serves as a skeleton.[14][15] These parent structures have specific names, such as pregnane, androstane, etc. The derivatives carry various functional groups called suffixes or prefixes after the respective numbers, indicating their position in the steroid nucleus.[16] There are widely used trivial steroid names of natural origin with significant biologic activity, such as progesterone, testosterone or cortisol. Some of these names are defined in The Nomenclature of Steroids.[17] These trivial names can also be used as a base to derive new names, however, by adding prefixes only rather than suffixes, e.g., the steroid 17α-hydroxyprogesterone has a hydroxy group (-OH) at position 17 of the steroid nucleus comparing to progesterone.

The letters α and β[18] denote absolute stereochemistry at chiral centers—a specific nomenclature distinct from the R/S convention[19] of organic chemistry to denote absolute configuration of functional groups, known as Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules. The R/S convention assigns priorities to substituents on a chiral center based on their atomic number. The highest priority group is assigned to the atom with the highest atomic number, and the lowest priority group is assigned to the atom with the lowest atomic number. The molecule is then oriented so that the lowest priority group points away from the viewer, and the remaining three groups are arranged in order of decreasing priority around the chiral center. If this arrangement is clockwise, it is assigned an R configuration; if it is counterclockwise, it is assigned an S configuration.[20] In contrast, steroid nomenclature uses α and β to denote stereochemistry at chiral centers. The α and β designations are based on the orientation of substituents relative to each other in a specific ring system. In general, α refers to a substituent that is oriented towards the plane of the ring system, while β refers to a substituent that is oriented away from the plane of the ring system. In steroids drawn from the standard perspective used in this paper, α-bonds are depicted on figures as dashed wedges and β-bonds as solid wedges.[14]

The name "11-deoxycortisol" is an example of a derived name that uses cortisol as a parent structure without an oxygen atom (hence "deoxy") attached to position 11 (as a part of a hydroxy group).[14][21] The numbering of positions of carbon atoms in the steroid nucleus is set in a template found in the Nomenclature of Steroids[22] that is used regardless of whether an atom is present in the steroid in question.[14]

Unsaturated carbons (generally, ones that are part of a double bond) in the steroid nucleus are indicated by changing -ane to -ene.[23] This change was traditionally done in the parent name, adding a prefix to denote the position, with or without Δ (Greek capital delta) which designates unsaturation, for example, 4-pregnene-11β,17α-diol-3,20-dione (also Δ4-pregnene-11β,17α-diol-3,20-dione) or 4-androstene-3,11,17-trione (also Δ4-androstene-3,11,17-trione). However, the Nomenclature of Steroids recommends the locant of a double bond to be always adjacent to the syllable designating the unsaturation, therefore, having it as a suffix rather than a prefix, and without the use of the Δ character, i.e. pregn-4-ene-11β,17α-diol-3,20-dione or androst-4-ene-3,11,17-trione. The double bond is designated by the lower-numbered carbon atom, i.e. "Δ4-" or "4-ene" means the double bond between positions 4 and 5. The saturation of carbons of a parent steroid can be done by adding "dihydro-" prefix,[24] i.e., a saturation of carbons 4 and 5 of testosterone with two hydrogen atoms is 4,5α-dihydrotestosterone or 4,5β-dihydrotestosterone. Generally, when there is no ambiguity, one number of a hydrogen position from a steroid with a saturated bond may be omitted, leaving only the position of the second hydrogen atom, e.g., 5α-dihydrotestosterone or 5β-dihydrotestosterone. The Δ5-steroids are those with a double bond between carbons 5 and 6 and the Δ4 steroids are those with a double bond between carbons 4 and 5.[25][23]

The abbreviations like "P4" for progesterone and "A4" for androstenedione for refer to Δ4-steroids, while "P5" for pregnenolone and "A5" for androstenediol refer to Δ5-steroids.[14]

The suffix -ol denotes a hydroxy group, while the suffix -one denotes an oxo group. When two or three identical groups are attached to the base structure at different positions, the suffix is indicated as -diol or -triol for hydroxy, and -dione or -trione for oxo groups, respectively. For example, 5α-pregnane-3α,17α-diol-20-one has a hydrogen atom at the 5α position (hence the "5α-" prefix), two hydroxy groups (-OH) at the 3α and 17α positions (hence "3α,17α-diol" suffix) and an oxo group (=O) at the position 20 (hence the "20-one" suffix). However, erroneous use of suffixes can be found, e.g., "5α-pregnan-17α-diol-3,11,20-trione"[26] [sic] — since it has just one hydroxy group (at 17α) rather than two, then the suffix should be -ol, rather than -diol, so that the correct name to be "5α-pregnan-17α-ol-3,11,20-trione".

According to the rule set in the Nomenclature of Steroids, the terminal "e" in the parent structure name should be elided before the vowel (the presence or absence of a number does not affect such elision).[14][16] This means, for instance, that if the suffix immediately appended to the parent structure name begins with a vowel, the trailing "e" is removed from that name. An example of such removal is "5α-pregnan-17α-ol-3,20-dione", where the last "e" of "pregnane" is dropped due to the vowel ("o") at the beginning of the suffix -ol. Some authors incorrectly use this rule, eliding the terminal "e" where it should be kept, or vice versa.[27]

The term "11-oxygenated" refers to the presence of an oxygen atom as an oxo (=O) or hydroxy (-OH) substituent at carbon 11. "Oxygenated" is consistently used within the chemistry of the steroids[28] since the 1950s.[29] Some studies use the term "11-oxyandrogens"[30][31] as an abbreviation for 11-oxygenated androgens, to emphasize that they all have an oxygen atom attached to carbon at position 11.[32][33] However, in chemical nomenclature, the prefix "oxy" is associated with ether functional groups, i.e., a compound with an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups (R-O-R),[34] therefore, using "oxy" within the name of a steroid class may be misleading. One can find clear examples of "oxygenated" to refer to a broad class of organic molecules containing a variety of oxygen containing functional groups in other domains of organic chemistry,[35] and it is appropriate to use this convention.[14]

Even though "keto" is a standard prefix in organic chemistry, the 1989 recommendations of the Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature discourage the application of the prefix "keto" for steroid names, and favor the prefix "oxo" (e.g., 11-oxo steroids rather than 11-keto steroids), because "keto" includes the carbon that is part of the steroid nucleus and the same carbon atom should not be specified twice.[36][14]

Species distribution

[edit]Steroids are present across all domains of life, including bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. In eukaryotes, steroids are particularly abundant in fungi, plants, and animals.[37][38]

Eukaryotic

[edit]Eukaryotic cells, encompassing animals, plants, fungi, and protists, are characterized by their complex cellular structures, including a true nucleus and membrane-bound organelles.[39] Sterols, a subgroup of steroids, play crucial roles in maintaining membrane fluidity, supporting cell signaling, and enhancing stress tolerance. These compounds are integral to eukaryotic membranes, where they contribute to membrane integrity and functionality.[40]

During eukaryogenesis—the evolutionary process that gave rise to modern eukaryotic cells—steroids likely facilitated the endosymbiotic acquisition of mitochondria.[41]

Prokaryotic

[edit]Although sterol biosynthesis is rare in prokaryotes, certain bacteria, including Methylococcus capsulatus, specific methanotrophs, myxobacteria, and the planctomycete Gemmata obscuriglobus, are capable of producing sterols. In G. obscuriglobus, sterols are essential for cell viability, but their roles in other bacteria remain poorly understood.[42]

Prokaryotic sterol synthesis involves the tetracyclic steroid framework, as found in myxobacteria,[43] as well as hopanoids, pentacyclic lipids that regulate bacterial membrane functions.[44] These sterol biosynthetic pathways may have originated in bacteria or been transferred from eukaryotes.[45]

Sterol synthesis depends on two key enzymes: squalene monooxygenase and oxidosqualene cyclase. Phylogenetic analyses of oxidosqualene cyclase (Osc) suggest that some bacterial Osc genes may have been acquired via horizontal gene transfer from eukaryotes, as certain bacterial Osc proteins closely resemble their eukaryotic homologs.[42]

Fungal

[edit]Fungal steroids include the ergosterols, which are involved in maintaining the integrity of the fungal cellular membrane. Various antifungal drugs, such as amphotericin B and azole antifungals, utilize this information to kill pathogenic fungi.[46] Fungi can alter their ergosterol content (e.g. through loss of function mutations in the enzymes ERG3 or ERG6, inducing depletion of ergosterol, or mutations that decrease the ergosterol content) to develop resistance to drugs that target ergosterol.[47]

Ergosterol is analogous to the cholesterol found in the cellular membranes of animals (including humans), or the phytosterols found in the cellular membranes of plants.[47] All mushrooms contain large quantities of ergosterol, in the range of tens to hundreds of milligrams per 100 grams of dry weight.[47] Oxygen is necessary for the synthesis of ergosterol in fungi.[47]

Ergosterol is responsible for the vitamin D content found in mushrooms; ergosterol is chemically converted into provitamin D2 by exposure to ultraviolet light.[47] Provitamin D2 spontaneously forms vitamin D2.[47] However, not all fungi utilize ergosterol in their cellular membranes; for example, the pathogenic fungal species Pneumocystis jirovecii does not, which has important clinical implications (given the mechanism of action of many antifungal drugs). Using the fungus Saccharomyces cerevisiae as an example, other major steroids include ergosta‐5,7,22,24(28)‐tetraen‐3β‐ol, zymosterol, and lanosterol. S. cerevisiae utilizes 5,6‐dihydroergosterol in place of ergosterol in its cell membrane.[47]

Plant

[edit]Plant steroids include steroidal alkaloids found in Solanaceae[48] and Melanthiaceae (specially the genus Veratrum),[49] cardiac glycosides,[50] the phytosterols and the brassinosteroids (which include several plant hormones).

Animal

[edit]Animal steroids include compounds of vertebrate and insect origin, the latter including ecdysteroids such as ecdysterone (controlling molting in some species). Vertebrate examples include the steroid hormones and cholesterol; the latter is a structural component of cell membranes that helps determine the fluidity of cell membranes and is a principal constituent of plaque (implicated in atherosclerosis [by whom?]). Steroid hormones include:

- Sex hormones, which influence sex differences and support puberty and reproduction. These include androgens, estrogens, and progestogens.

- Corticosteroids, including most synthetic steroid drugs, with natural product classes the glucocorticoids (which regulate many aspects of metabolism and immune function) and the mineralocorticoids (which help maintain blood volume and control renal excretion of electrolytes)

- Anabolic steroids, natural and synthetic, which interact with androgen receptors to increase muscle and bone synthesis. In popular use, the term "steroids" often refers to anabolic steroids.

Types

[edit]By function

[edit]This section needs expansion with: A more detailed explanation of function would also be beneficial. You can help by adding to it. (January 2019) |

The major classes of steroid hormones, with prominent members and examples of related functions, are:[51][52]

- Corticosteroids:

- Glucocorticoids:

- Cortisol, a glucocorticoid whose functions include stress response and immunosuppression

- Mineralocorticoids:

- Aldosterone, a mineralocorticoid that helps regulate blood pressure through water and electrolyte balance in the kidneys

- Glucocorticoids:

- Sex steroids:

- Progestogens:

- Progesterone, which regulates cyclical changes in the endometrium of the uterus and maintains a pregnancy

- Androgens:

- Testosterone, which contributes to the development and maintenance of male secondary sex characteristics

- Estrogens:

- Estradiol, which contributes to the development and maintenance of female secondary sex characteristics

- Progestogens:

Additional classes of steroids include:

- Neurosteroids such as DHEA and allopregnanolone

- Bile acids such as taurocholic acid

- Aminosteroid neuromuscular blocking agents (mainly synthetic) such as pancuronium bromide

- Steroidal antiandrogens (mainly synthetic) such as cyproterone acetate

- Steroidogenesis inhibitors (mainly exogenous) such as alfatradiol

- Membrane sterols such as cholesterol, ergosterol, and various phytosterols

- Toxins such as steroidal saponins and cardenolides/cardiac glycosides

As well as the following class of secosteroids (open-ring steroids):

- Vitamin D forms such as ergocalciferol, cholecalciferol, and calcitriol

By structure

[edit]Intact ring system

[edit]Steroids can be classified based on their chemical composition.[53] One example of how MeSH performs this classification is available at the Wikipedia MeSH catalog. Examples of this classification include:

| Class | Example | Number of carbon atoms |

|---|---|---|

| Cholestanes | Cholesterol | 27 |

| Cholanes | Cholic acid | 24 |

| Pregnanes | Progesterone | 21 |

| Androstanes | Testosterone | 19 |

| Estranes | Estradiol | 18 |

In biology, it is common to name the above steroid classes by the number of carbon atoms present when referring to hormones: C18-steroids for the estranes (mostly estrogens), C19-steroids for the androstanes (mostly androgens), and C21-steroids for the pregnanes (mostly corticosteroids).[54] The classification "17-ketosteroid" is also important in medicine.

The gonane (steroid nucleus) is the parent 17-carbon tetracyclic hydrocarbon molecule with no alkyl sidechains.[55]

Cleaved, contracted, and expanded rings

[edit]Secosteroids (Latin seco, "to cut") are a subclass of steroidal compounds resulting, biosynthetically or conceptually, from scission (cleavage) of parent steroid rings (generally one of the four). Major secosteroid subclasses are defined by the steroid carbon atoms where this scission has taken place. For instance, the prototypical secosteroid cholecalciferol, vitamin D3 (shown), is in the 9,10-secosteroid subclass and derives from the cleavage of carbon atoms C-9 and C-10 of the steroid B-ring; 5,6-secosteroids and 13,14-steroids are similar.[56]

Norsteroids (nor-, L. norma; "normal" in chemistry, indicating carbon removal)[57] and homosteroids (homo-, Greek homos; "same", indicating carbon addition) are structural subclasses of steroids formed from biosynthetic steps. The former involves enzymic ring expansion-contraction reactions, and the latter is accomplished (biomimetically) or (more frequently) through ring closures of acyclic precursors with more (or fewer) ring atoms than the parent steroid framework.[58]

Combinations of these ring alterations are known in nature. For instance, ewes who graze on corn lily ingest cyclopamine (shown) and veratramine, two of a sub-family of steroids where the C- and D-rings are contracted and expanded respectively via a biosynthetic migration of the original C-13 atom. Ingestion of these C-nor-D-homosteroids results in birth defects in lambs: cyclopia from cyclopamine and leg deformity from veratramine.[59] A further C-nor-D-homosteroid (nakiterpiosin) is excreted by Okinawan cyanobacteriosponges. e.g., Terpios hoshinota, leading to coral mortality from black coral disease.[60] Nakiterpiosin-type steroids are active against the signaling pathway involving the smoothened and hedgehog proteins, a pathway which is hyperactive in a number of cancers.[citation needed]

Biological significance

[edit]Steroids and their metabolites often function as signalling molecules (the most notable examples are steroid hormones), and steroids and phospholipids are components of cell membranes.[61] Steroids such as cholesterol decrease membrane fluidity.[62] Similar to lipids, steroids are highly concentrated energy stores. However, they are not typically sources of energy; in mammals, they are normally metabolized and excreted.[citation needed]

Steroids play critical roles in a number of disorders, including malignancies like prostate cancer, where steroid production inside and outside the tumour promotes cancer cell aggressiveness.[63]

Biosynthesis and metabolism

[edit]

The hundreds of steroids found in animals, fungi, and plants are made from lanosterol (in animals and fungi; see examples above) or cycloartenol (in other eukaryotes). Both lanosterol and cycloartenol derive from cyclization of the triterpenoid squalene.[4] Lanosterol and cycloartenol are sometimes called protosterols because they serve as the starting compounds for all other steroids.

Steroid biosynthesis is an anabolic pathway which produces steroids from simple precursors. A unique biosynthetic pathway is followed in animals (compared to many other organisms), making the pathway a common target for antibiotics and other anti-infection drugs. Steroid metabolism in humans is also the target of cholesterol-lowering drugs, such as statins. In humans and other animals the biosynthesis of steroids follows the mevalonate pathway, which uses acetyl-CoA as building blocks for dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP).[64][better source needed]

In subsequent steps DMAPP and IPP conjugate to form farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), which further conjugates with each other to form the linear triterpenoid squalene. Squalene biosynthesis is catalyzed by squalene synthase, which belongs to the squalene/phytoene synthase family. Subsequent epoxidation and cyclization of squalene generate lanosterol, which is the starting point for additional modifications into other steroids (steroidogenesis).[65] In other eukaryotes, the cyclization product of epoxidized squalene (oxidosqualene) is cycloartenol.

Mevalonate pathway

[edit]

The mevalonate pathway (also called HMG-CoA reductase pathway) begins with acetyl-CoA and ends with dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) and isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP).

DMAPP and IPP donate isoprene units, which are assembled and modified to form terpenes and isoprenoids[66] (a large class of lipids, which include the carotenoids and form the largest class of plant natural products).[67] Here, the activated isoprene units are joined to make squalene and folded into a set of rings to make lanosterol.[68] Lanosterol can then be converted into other steroids, such as cholesterol and ergosterol.[68][69]

Two classes of drugs target the mevalonate pathway: statins (like rosuvastatin), which are used to reduce elevated cholesterol levels,[70] and bisphosphonates (like zoledronate), which are used to treat a number of bone-degenerative diseases.[71]

Steroidogenesis

[edit]

Steroidogenesis is the biological process by which steroids are generated from cholesterol and changed into other steroids.[73] The pathways of steroidogenesis differ among species. The major classes of steroid hormones, as noted above (with their prominent members and functions), are the progestogens, corticosteroids (corticoids), androgens, and estrogens.[25][74] Human steroidogenesis of these classes occurs in a number of locations:

- Progestogens are the precursors of all other human steroids, and all human tissues which produce steroids must first convert cholesterol to pregnenolone. This conversion is the rate-limiting step of steroid synthesis, which occurs inside the mitochondrion of the respective tissue. It is catalyzed by the mitochondrial P450scc system.[75][76]

- Cortisol, corticosterone, aldosterone are produced in the adrenal cortex.[25][74]

- Estradiol, estrone and progesterone are made primarily in the ovary, estriol in placenta during pregnancy, and testosterone primarily in the testes[25][77][78][79] (some testosterone may also be produced in the adrenal cortex).[25][74]

- Estradiol is converted from testosterone directly (in males), or via the primary pathway DHEA – androstenedione – estrone and secondarily via testosterone (in females).[25]

- Stromal cells have been shown to produce steroids in response to signaling produced by androgen-starved prostate cancer cells.[63][non-primary source needed][better source needed]

- Some neurons and glia in the central nervous system (CNS) express the enzymes required for the local synthesis of pregnenolone, progesterone, DHEA and DHEAS, de novo or from peripheral sources.[25][citation needed]

| Sex | Sex hormone | Reproductive phase |

Blood production rate |

Gonadal secretion rate |

Metabolic clearance rate |

Reference range (serum levels) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI units | Non-SI units | ||||||

| Men | Androstenedione | –

|

2.8 mg/day | 1.6 mg/day | 2200 L/day | 2.8–7.3 nmol/L | 80–210 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | –

|

6.5 mg/day | 6.2 mg/day | 950 L/day | 6.9–34.7 nmol/L | 200–1000 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | –

|

150 μg/day | 110 μg/day | 2050 L/day | 37–250 pmol/L | 10–70 pg/mL | |

| Estradiol | –

|

60 μg/day | 50 μg/day | 1600 L/day | <37–210 pmol/L | 10–57 pg/mL | |

| Estrone sulfate | –

|

80 μg/day | Insignificant | 167 L/day | 600–2500 pmol/L | 200–900 pg/mL | |

| Women | Androstenedione | –

|

3.2 mg/day | 2.8 mg/day | 2000 L/day | 3.1–12.2 nmol/L | 89–350 ng/dL |

| Testosterone | –

|

190 μg/day | 60 μg/day | 500 L/day | 0.7–2.8 nmol/L | 20–81 ng/dL | |

| Estrone | Follicular phase | 110 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 110–400 pmol/L | 30–110 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 260 μg/day | 150 μg/day | 2200 L/day | 310–660 pmol/L | 80–180 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 40 μg/day | Insignificant | 1610 L/day | 22–230 pmol/L | 6–60 pg/mL | ||

| Estradiol | Follicular phase | 90 μg/day | 80 μg/day | 1200 L/day | <37–360 pmol/L | 10–98 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 250 μg/day | 240 μg/day | 1200 L/day | 699–1250 pmol/L | 190–341 pg/mL | ||

| Postmenopause | 6 μg/day | Insignificant | 910 L/day | <37–140 pmol/L | 10–38 pg/mL | ||

| Estrone sulfate | Follicular phase | 100 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 700–3600 pmol/L | 250–1300 pg/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 180 μg/day | Insignificant | 146 L/day | 1100–7300 pmol/L | 400–2600 pg/mL | ||

| Progesterone | Follicular phase | 2 mg/day | 1.7 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 0.3–3 nmol/L | 0.1–0.9 ng/mL | |

| Luteal phase | 25 mg/day | 24 mg/day | 2100 L/day | 19–45 nmol/L | 6–14 ng/mL | ||

Notes and sources

Notes: "The concentration of a steroid in the circulation is determined by the rate at which it is secreted from glands, the rate of metabolism of precursor or prehormones into the steroid, and the rate at which it is extracted by tissues and metabolized. The secretion rate of a steroid refers to the total secretion of the compound from a gland per unit time. Secretion rates have been assessed by sampling the venous effluent from a gland over time and subtracting out the arterial and peripheral venous hormone concentration. The metabolic clearance rate of a steroid is defined as the volume of blood that has been completely cleared of the hormone per unit time. The production rate of a steroid hormone refers to entry into the blood of the compound from all possible sources, including secretion from glands and conversion of prohormones into the steroid of interest. At steady state, the amount of hormone entering the blood from all sources will be equal to the rate at which it is being cleared (metabolic clearance rate) multiplied by blood concentration (production rate = metabolic clearance rate × concentration). If there is little contribution of prohormone metabolism to the circulating pool of steroid, then the production rate will approximate the secretion rate." Sources: See template. | |||||||

Alternative pathways

[edit]In plants and bacteria, the non-mevalonate pathway (MEP pathway) uses pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate as substrates to produce IPP and DMAPP.[66][80]

During diseases pathways otherwise not significant in healthy humans can become utilized. For example, in one form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia a deficiency in the 21-hydroxylase enzymatic pathway leads to an excess of 17α-Hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) – this pathological excess of 17-OHP in turn may be converted to dihydrotestosterone (DHT, a potent androgen) through among others 17,20 Lyase (a member of the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes), 5α-Reductase and 3α-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase.[81]

Catabolism and excretion

[edit]Steroids are primarily oxidized by cytochrome P450 oxidase enzymes, such as CYP3A4. These reactions introduce oxygen into the steroid ring, allowing the cholesterol to be broken up by other enzymes into bile acids.[82] These acids can then be eliminated by secretion from the liver in bile.[83] The expression of the oxidase gene can be upregulated by the steroid sensor PXR when there is a high blood concentration of steroids.[84] Steroid hormones, lacking the side chain of cholesterol and bile acids, are typically hydroxylated at various ring positions or oxidized at the 17 position, conjugated with sulfate or glucuronic acid and excreted in the urine.[85]

Isolation, structure determination, and methods of analysis

[edit]Steroid isolation, depending on context, is the isolation of chemical matter required for chemical structure elucidation, derivitzation or degradation chemistry, biological testing, and other research needs (generally milligrams to grams, but often more[86] or the isolation of "analytical quantities" of the substance of interest (where the focus is on identifying and quantifying the substance (for example, in biological tissue or fluid). The amount isolated depends on the analytical method, but is generally less than one microgram.[87][page needed]

The methods of isolation to achieve the two scales of product are distinct, but include extraction, precipitation, adsorption, chromatography, and crystallization. In both cases, the isolated substance is purified to chemical homogeneity; combined separation and analytical methods, such as LC-MS, are chosen to be "orthogonal"—achieving their separations based on distinct modes of interaction between substance and isolating matrix—to detect a single species in the pure sample.

Structure determination refers to the methods to determine the chemical structure of an isolated pure steroid, using an evolving array of chemical and physical methods which have included NMR and small-molecule crystallography.[2]: 10–19 Methods of analysis overlap both of the above areas, emphasizing analytical methods to determining if a steroid is present in a mixture and determining its quantity.[87]

Chemical synthesis

[edit]Microbial catabolism of phytosterol side chains yields C-19 steroids, C-22 steroids, and 17-ketosteroids (i.e. precursors to adrenocortical hormones and contraceptives).[88][89][90] The addition and modification of functional groups is key when producing the wide variety of medications available within this chemical classification. These modifications are performed using conventional organic synthesis and/or biotransformation techniques.[91][92]

Precursors

[edit]Semisynthesis

[edit]The semisynthesis of steroids often begins from precursors such as cholesterol,[90] phytosterols,[89] or sapogenins.[93] The efforts of Syntex, a company involved in the Mexican barbasco trade, used Dioscorea mexicana to produce the sapogenin diosgenin in the early days of the synthetic steroid pharmaceutical industry.[86]

Total synthesis

[edit]Some steroidal hormones are economically obtained only by total synthesis from petrochemicals (e.g. 13-alkyl steroids).[90] For example, the pharmaceutical Norgestrel begins from methoxy-1-tetralone, a petrochemical derived from phenol.

Research awards

[edit]A number of Nobel Prizes have been awarded for steroid research, including:

- 1927 (Chemistry) Heinrich Otto Wieland — Constitution of bile acids and sterols and their connection to vitamins[94]

- 1928 (Chemistry) Adolf Otto Reinhold Windaus — Constitution of sterols and their connection to vitamins[95]

- 1939 (Chemistry) Adolf Butenandt and Leopold Ružička — Isolation and structural studies of steroid sex hormones, and related studies on higher terpenes[96]

- 1950 (Physiology or Medicine) Edward Calvin Kendall, Tadeus Reichstein, and Philip Hench — Structure and biological effects of adrenal hormones[97]

- 1965 (Chemistry) Robert Burns Woodward — In part, for the synthesis of cholesterol, cortisone, and lanosterol[98]

- 1969 (Chemistry) Derek Barton and Odd Hassel — Development of the concept of conformation in chemistry, emphasizing the steroid nucleus[99]

- 1975 (Chemistry) Vladimir Prelog — In part, for developing methods to determine the stereochemical course of cholesterol biosynthesis from mevalonic acid via squalene[100]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Moss GP, the Working Party of the IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (1989). "Nomenclature of steroids, recommendations 1989" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 61 (10): 1783–1822. doi:10.1351/pac198961101783. S2CID 97612891. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2012. Also available with the same authors at "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989". European Journal of Biochemistry. 186 (3): 429–458. December 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099.; Also available online at "The Nomenclature of Steroids". London, GBR: Queen Mary University of London. p. 3S-1.4. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Lednicer D (2011). Steroid Chemistry at a Glance. Hoboken: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-66084-3.

- ^ Rhen T, Cidlowski JA (October 2005). "Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids--new mechanisms for old drugs". The New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (16): 1711–1723. doi:10.1056/NEJMra050541. PMID 16236742. S2CID 5744727.

- ^ a b "Lanosterol biosynthesis". Recommendations on Biochemical & Organic Nomenclature, Symbols & Terminology. International Union Of Biochemistry And Molecular Biology. Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ Yang Y, Krin A, Cai X, Poopari MR, Zhang Y, Cheeseman JR, Xu Y (January 2023). "Conformations of Steroid Hormones: Infrared and Vibrational Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy". Molecules. 28 (2): 771. doi:10.3390/molecules28020771. PMC 9864676. PMID 36677830.

- ^ Also available in print at Hill RA, Makin HL, Kirk DN, Murphy GM (1991). Dictionary of Steroids. London, GBR: Chapman and Hall. pp. xxx–lix. ISBN 978-0-412-27060-4. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Harper D. "sterol | Etymology, origin and meaning of sterol by etymonline". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ Chevreul ME (8 May 1815). "Recherches chimiques sur les corps gras, et particulièrement sur leurs combinaisons avec les alcalis. Sixième mémoire. Examen des graisses d'homme, de mouton, de boeuf, de jaguar et d'oie" [Chemical research on fatty substances, and particularly on their combinations with alkalis. Sixth memoir. Examination of human, sheep, beef, jaguar and goose fats]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (Annals of Chemistry and Physics) (in French). 2: 339–372. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2023 – via Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek.

- ^ Arago F, Gay-Lussac JL (1816). Annales de chimie et de physique (Annals of Chemistry and Physics) (in French). Chez Crochard. p. 346.

"Je nommerai cholesterine, de χολη, bile, et στερεος, solide, la substance cristallisée des calculs biliares humains, ... " (I will name cholesterine – from χολη (bile) and στερεος (solid) – the crystalized substance from human gallstones ... )

- ^ "R-2.4.1 Fusion nomenclature". Archived from the original on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Rogozkin VA (14 June 1991). "Anabolic Androgenic Steroids: Structure, Nomenclature, and Classification, Biological Properties". Metabolism of Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids. CRC Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-8493-6415-0.

The steroid structural base is a steran nucleus, a polycyclic C17 steran skeleton consisting of three condensed cyclohexane rings in nonlinear or phenanthrene junction (A, B, and C), and a cyclopentane ring (D).1,2

[permanent dead link] - ^ Urich K (16 September 1994). "Sterols and Steroids". Comparative Animal Biochemistry. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 624–. ISBN 978-3-540-57420-0.

- ^ Greep 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Masiutin MM, Yadav MK (3 April 2023). "Alternative androgen pathways" (PDF). WikiJournal of Medicine. 10: 29. doi:10.15347/WJM/2023.003. S2CID 257943362.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989". Eur J Biochem. 186 (3): 430. 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099. p. 430:

3S‐1.0. Definition of steroids and sterols. Steroids are compounds possessing the skeleton of cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene or a skeleton derived therefrom by one or more bond scissions or ring expansions or contractions. Methyl groups are normally present at C-10 and C-13. An alkyl side chain may also be present at C-17. Sterols are steroids carrying a hydroxyl group at C-3 and most of the skeleton of cholestane.

- ^ a b "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989". Eur J Biochem. 186 (3): 429–458. 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099. p. 441:

3S-4. FUNCTIONAL GROUPS. 3S-4.0. General. Nearly all biologically important steroids are derivatives of the parent hydrocarbons (cf. Table 1) carrying various functional groups. [...] Suffixes are added to the name of the saturated or unsaturated parent system (see 33-2.5), the terminal e of -ane, -ene, -yne, -adiene etc. being elided before a vowel (presence or absence of numerals has no effect on such elisions).

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989, chapter 3S-4.9". European Journal of Biochemistry. 186 (3): 429–458. December 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099. Archived from the original on 19 February 2024. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

3S‐4.9. Trivial names of important steroids Examples of trivial names retained for important steroid derivatives, these being mostly natural compounds of significant biological activity, are given in Table 2

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989, chapter 3S-1.4". European Journal of Biochemistry. 186 (3): 429–458. December 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099. p. 431:

3S‐1.4. Orientation of projection formulae. When the rings of a steroid are denoted as projections onto the plane of the paper, the formula is normally to be oriented as in 2a. An atom or group attached to a ring depicted as in the orientation 2a is termed α (alpha) if it lies below the plane of the paper or β (beta) if it lies above the plane of the paper.

- ^ Favre HA, Powell WH (2014). "P-91". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry – IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4. p. 868:

P‐91.2.1.1 Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) stereodescriptors. Some stereodescriptors described in the Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) priority system, called 'CIP stereodescriptors', are recommended to specify the configuration of organic compounds, as described and exemplified in this Chapter and applied in Chapters P‐1 through P‐8, and in the nomenclature of natural products in Chapter P-10. The following stereodescriptors are used as preferred stereodescriptors (see P‐92.1.2): (a) 'R' and 'S', to designate the absolute configuration of tetracoordinate (quadriligant) chirality centers;

- ^ "3.5: Naming chiral centers- the R and S system". 11 August 2018. Archived from the original on 1 November 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Favre HA, Powell WH (2014). "P-13.8.1.1". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry – IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4. p. 66:

P‐13.8.1.1 The prefix 'de' (not 'des'), followed by the name of a group or atom (other than hydrogen), denotes removal (or loss) of that group and addition of the necessary hydrogen atoms, i.e., exchange of that group with hydrogen atoms. As an exception, 'deoxy', when applied to hydroxy compounds, denotes the removal of an oxygen atom from an –OH group with the reconnection of the hydrogen atom. 'Deoxy' is extensively used as a subtractive prefix in carbohydrate nomenclature (see P‐102.5.3).

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989". Eur J Biochem. 186 (3): 430. 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099. p. 430:

3S-1.1. Numbering and ring letters. Steroids are numbered and rings are lettered as in formula 1

- ^ a b "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989". Eur J Biochem. 186 (3): 436–437. 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099. p. 436-437:

3S‐2.5 Unsaturation. Unsaturation is indicated by changing -ane to -ene, -adiene, -yne etc., or -an- to -en-, -adien-, -yn- etc. Examples: Androst-5-ene, not 5-androstene; 5α-Cholest-6-ene; 5β-Cholesta-7,9(11)-diene; 5α-Cholest-6-en-3β-ol. Notes. 1) It is now recommended that the locant of a double bond is always adjacent to the syllable designating the unsaturation.[...] 3) The use of Δ (Greek capital delta) character is not recommended to designate unsaturation in individual names. It may be used, however, in generic terms, like 'Δ5-steroids'

- ^ Favre HA, Powell WH (2014). "P-3". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry – IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

P-31.2.2 General methodology. 'Hydro' and 'dehydro' prefixes are associated with hydrogenation and dehydrogenation, respectively, of a double bond; thus, multiplying prefixes of even values, as 'di', 'tetra', etc. are used to indicate the saturation of double bond(s), for example 'dihydro', 'tetrahydro'; or creation of double (or triple) bonds, as 'didehydro', etc. In names, they are placed immediately at the front of the name of the parent hydride and in front of any nondetachable prefixes. Indicated hydrogen atoms have priority over 'hydro' prefixes for low locants. If indicated hydrogen atoms are present in a name, the 'hydro' prefixes precede them.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller WL, Auchus RJ (February 2011). "The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders". Endocr Rev. 32 (1): 81–151. doi:10.1210/er.2010-0013. PMC 3365799. PMID 21051590.

- ^ "Google Scholar search results for "5α-pregnan-17α-diol-3,11,20-trione" that is an incorrect name". 2022. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Google Scholar search results for "5α-pregnane-17α-ol-3,20-dione" that is an incorrect name". 2022. Archived from the original on 7 October 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Makin HL, Trafford DJ (1972). "The chemistry of the steroids". Clinics in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1 (2): 333–360. doi:10.1016/S0300-595X(72)80024-0.

- ^ Bongiovanni AM, Clayton GW (March 1954). "Simplified method for estimation of 11-oxygenated neutral 17-ketosteroids in urine of individuals with adrenocortical hyperplasia". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 85 (3): 428–429. doi:10.3181/00379727-85-20905. PMID 13167092. S2CID 8408420.

- ^ Slaunwhite Jr WR, Neely L, Sandberg AA (1964). "The metabolism of 11-Oxyandrogens in human subjects". Steroids. 3 (4): 391–416. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(64)90003-0.

- ^ Taylor AE, Ware MA, Breslow E, Pyle L, Severn C, Nadeau KJ, et al. (July 2022). "11-Oxyandrogens in Adolescents With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". Journal of the Endocrine Society. 6 (7) bvac037. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvac037. PMC 9123281. PMID 35611324.

- ^ Turcu AF, Rege J, Auchus RJ, Rainey WE (May 2020). "11-Oxygenated androgens in health and disease". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 16 (5): 284–296. doi:10.1038/s41574-020-0336-x. PMC 7881526. PMID 32203405.

- ^ Barnard L, du Toit T, Swart AC (April 2021). "Back where it belongs: 11β-hydroxyandrostenedione compels the re-assessment of C11-oxy androgens in steroidogenesis". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 525 111189. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2021.111189. PMID 33539964. S2CID 231776716.

- ^ Favre H, Powell W (2014). "Appendix 2". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry – IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4. p. 1112:

oxy* –O– P-15.3.1.2.1.1; P-63.2.2.1.1

- ^ Barrientos EJ, Lapuerta M, Boehman AL (August 2013). "Group additivity in soot formation for the example of C-5 oxygenated hydrocarbon fuels". Combustion and Flame. 160 (8): 1484–1498. Bibcode:2013CoFl..160.1484B. doi:10.1016/j.combustflame.2013.02.024.

- ^ "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN). The nomenclature of steroids. Recommendations 1989". Eur J Biochem. 186 (3): 429–58. 1989. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15228.x. PMID 2606099. p. 430:

The prefix oxo- should also be used in connection with generic terms, e.g., 17-oxo steroids. The term '17-keto steroids', often used in the medical literature, is incorrect because C-17 is specified twice, as the term keto denotes C=O

- ^ Biological significance of steroids. Archived from the original on 12 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "17.2C: Steroids". Biology Libretexts. 3 July 2018. Archived from the original on 12 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ Hoshino Y, Gaucher EA (2021). "Steroids distribution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (25). doi:10.1073/pnas.2101276118. PMC 8237579. PMID 34131078.

- ^ "Steroids distribution". Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Hoshino Y, Gaucher EA (2021). "Species distribution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 118 (25). doi:10.1073/pnas.2101276118. PMC 8237579. PMID 34131078.

- ^ a b Franke JD (2021). "Sterol Biosynthetic Pathways and Their Function in Bacteria.". In Villa TG, de Miguel Bouzas T (eds.). Developmental Biology in Prokaryotes and Lower Eukaryotes. Cham: Springer. pp. 215–227. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-77595-7_9. ISBN 978-3-030-77595-7.

- ^ Bode HB, Zeggel B, Silakowski B, Wenzel SC, Reichenbach H, Müller R (January 2003). "Steroid biosynthesis in prokaryotes: identification of myxobacterial steroids and cloning of the first bacterial 2,3(S)-oxidosqualene cyclase from the myxobacterium Stigmatella aurantiaca". Molecular Microbiology. 47 (2): 471–81. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03309.x. PMID 12519197. S2CID 37959511.

- ^ Siedenburg G, Jendrossek D (June 2011). "Squalene-hopene cyclases". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 77 (12): 3905–15. Bibcode:2011ApEnM..77.3905S. doi:10.1128/AEM.00300-11. PMC 3131620. PMID 21531832.

- ^ Desmond E, Gribaldo S (2009). "Phylogenomics of sterol synthesis: insights into the origin, evolution, and diversity of a key eukaryotic feature". Genome Biology and Evolution. 1: 364–81. doi:10.1093/gbe/evp036. PMC 2817430. PMID 20333205.

- ^ Bhetariya PJ, Sharma N, Singh P, Tripathi P, Upadhyay SK, Gautam P (21 March 2017). "Human Fungal Pathogens and Drug Resistance Against Azole Drugs". In Arora C, Sajid A, Kalia V (eds.). Drug Resistance in Bacteria, Fungi, Malaria, and Cancer. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-48683-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kavanagh K, ed. (8 September 2017). Fungi: Biology and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-1-119-37431-2.

- ^ Wink M (September 2003). "Evolution of secondary metabolites from an ecological and molecular phylogenetic perspective". Phytochemistry. 64 (1): 3–19. Bibcode:2003PChem..64....3W. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00300-5. PMID 12946402.

- ^ Wink M, Van Wyk BE (2008). Mind-altering and poisonous plants of the world. Portland (Oregon USA) and Salusbury (London England): Timber press inc. pp. 252, 253 and 254. ISBN 978-0-88192-952-2.

- ^ Wink M, van Wyk BE (2008). Mind-altering and poisonous plants of the world. Portland (Oregon USA) and Salusbury (London England): Timber press inc. pp. 324, 325 and 326. ISBN 978-0-88192-952-2.

- ^ Ericson-Neilsen W, Kaye AD (2014). "Steroids: pharmacology, complications, and practice delivery issues". Ochsner J. 14 (2): 203–7. PMC 4052587. PMID 24940130.

- ^ "International Journal of Molecular Sciences". Archived from the original on 12 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ Zorea A (2014). Steroids (Health and Medical Issues Today). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-1-4408-0299-7.

- ^ "C19-steroid hormone biosynthetic pathway – Ontology Browser – Rat Genome Database". rgd.mcw.edu. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Edgren RA, Stanczyk FZ (December 1999). "Nomenclature of the gonane progestins". Contraception. 60 (6): 313. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(99)00101-8. PMID 10715364.

- ^ Hanson JR (June 2010). "Steroids: partial synthesis in medicinal chemistry". Natural Product Reports. 27 (6): 887–99. doi:10.1039/c001262a. PMID 20424788.

- ^ "IUPAC Recommendations: Skeletal Modification in Revised Section F: Natural Products and Related Compounds (IUPAC Recommendations 1999)". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). 1999. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Wolfing J (2007). "Recent developments in the isolation and synthesis of D-homosteroids and related compounds". Arkivoc. 2007 (5): 210–230. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0008.517. hdl:2027/spo.5550190.0008.517. Archived from the original on 1 February 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Gao G, Chen C (2012). "Nakiterpiosin". In Corey EJ, Li JJ (eds.). Total synthesis of natural products: at the frontiers of organic chemistry. Berlin: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-34065-9. ISBN 978-3-642-34064-2. S2CID 92690863.

- ^ Uemura E, Kita M, Arimoto H, Kitamura M (2009). "Recent aspects of chemical ecology: Natural toxins, coral communities, and symbiotic relationships". Pure Appl. Chem. 81 (6): 1093–1111. doi:10.1351/PAC-CON-08-08-12.

- ^ Silverthorn DU, Johnson BR, Ober WC, Ober CE, Silverthorn AC (2016). Human physiology : an integrated approach (Seventh ed.). [San Francisco]: Sinauer Associates; W.H. Freeman & Co. ISBN 978-0-321-98122-6. OCLC 890107246.

- ^ Sadava D, Hillis DM, Heller HC, Berenbaum MR (2011). Life: The Science of Biology (9 ed.). San Francisco: Freeman. pp. 105–114. ISBN 978-1-4292-4646-0.

- ^ a b Lubik AA, Nouri M, Truong S, Ghaffari M, Adomat HH, Corey E, Cox ME, Li N, Guns ES, Yenki P, Pham S, Buttyan R (2016). "Paracrine Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Contributes Significantly to Acquired Steroidogenesis in the Prostate Tumor Microenvironment". Int. J. Cancer. 140 (2): 358–369. doi:10.1002/ijc.30450. PMID 27672740. S2CID 2354209.

- ^ Grochowski LL, Xu H, White RH (May 2006). "Methanocaldococcus jannaschii uses a modified mevalonate pathway for biosynthesis of isopentenyl diphosphate". Journal of Bacteriology. 188 (9): 3192–8. doi:10.1128/JB.188.9.3192-3198.2006. PMC 1447442. PMID 16621811.

- ^ Chatuphonprasert W, Jarukamjorn K, Ellinger I (12 September 2018). "Physiology and Pathophysiology of Steroid Biosynthesis, Transport and Metabolism in the Human Placenta". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 9 1027. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.01027. ISSN 1663-9812. PMC 6144938. PMID 30258364.

- ^ a b Kuzuyama T, Seto H (April 2003). "Diversity of the biosynthesis of the isoprene units". Natural Product Reports. 20 (2): 171–83. doi:10.1039/b109860h. PMID 12735695.

- ^ Dubey VS, Bhalla R, Luthra R (September 2003). "An overview of the non-mevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis in plants" (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 28 (5): 637–46. doi:10.1007/BF02703339. PMID 14517367. S2CID 27523830. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2007.

- ^ a b Schroepfer GJ (1981). "Sterol biosynthesis". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 50: 585–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.003101. PMID 7023367.

- ^ Lees ND, Skaggs B, Kirsch DR, Bard M (March 1995). "Cloning of the late genes in the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae—a review". Lipids. 30 (3): 221–6. doi:10.1007/BF02537824. PMID 7791529. S2CID 4019443.

- ^ Kones R (December 2010). "Rosuvastatin, inflammation, C-reactive protein, JUPITER, and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease—a perspective". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 4: 383–413. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S10812. PMC 3023269. PMID 21267417.

- ^ Roelofs AJ, Thompson K, Gordon S, Rogers MJ (October 2006). "Molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates: current status". Clinical Cancer Research. 12 (20 Pt 2): 6222s – 6230s. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0843. PMID 17062705. S2CID 9734002.

- ^ Häggström M, Richfield D (2014). "Diagram of the pathways of human steroidogenesis". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (1). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.005. ISSN 2002-4436.

- ^ Hanukoglu I (December 1992). "Steroidogenic enzymes: structure, function, and role in regulation of steroid hormone biosynthesis". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 43 (8): 779–804. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(92)90307-5. PMID 22217824. S2CID 112729. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Oestlund I, Snoep J, Schiffer L, Wabitsch M, Arlt W, Storbeck KH (February 2024). "The glucocorticoid-activating enzyme 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 catalyzes the activation of testosterone". J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 236 106436. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2023.106436. hdl:10044/1/108335. PMID 38035948.

- ^ Hanukoglu I, Jefcoate CR (April 1980). "Mitochondrial cytochrome P-450scc. Mechanism of electron transport by adrenodoxin". J Biol Chem. 255 (7): 3057–61. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)85851-9. PMID 6766943.

- ^ Hanukoglu I, Privalle CT, Jefcoate CR (May 1981). "Mechanisms of ionic activation of adrenal mitochondrial cytochromes P-450scc and P-45011 beta". J Biol Chem. 256 (9): 4329–35. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)69437-8. PMID 6783659.

- ^ "Reproductive Hormones". 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 10 February 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ Davis HC, Hackney AC (2017). "The Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Ovarian Axis and Oral Contraceptives: Regulation and Function". Sex Hormones, Exercise and Women. pp. 1–17. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44558-8_1. ISBN 978-3-319-44557-1.

- ^ androgen. 19 January 2024. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ Lichtenthaler HK (June 1999). "The 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in plants". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 50: 47–65. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.47. PMID 15012203.

- ^ Witchel SF, Azziz R (2010). "Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia". International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology. 2010: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2010/625105. PMC 2910408. PMID 20671993.

- ^ Pikuleva IA (December 2006). "Cytochrome P450s and cholesterol homeostasis". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 112 (3): 761–73. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.05.014. PMID 16872679.

- ^ Zollner G, Marschall HU, Wagner M, Trauner M (2006). "Role of nuclear receptors in the adaptive response to bile acids and cholestasis: pathogenetic and therapeutic considerations". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 3 (3): 231–51. doi:10.1021/mp060010s. PMID 16749856.

- ^ Kliewer SA, Goodwin B, Willson TM (October 2002). "The nuclear pregnane X receptor: a key regulator of xenobiotic metabolism". Endocrine Reviews. 23 (5): 687–702. doi:10.1210/er.2001-0038. PMID 12372848.

- ^ Steimer T. "Steroid Hormone Metabolism". WHO Collaborating Centre in Education and Research in Human Reproduction. Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Russell Marker Creation of the Mexican Steroid Hormone Industry". International Historic Chemical Landmark. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ a b Makin HL, Honor JW, Shackleton CH, Griffiths WJ (2010). "General methods for the extraction, purification, and measurement of steroids by chromatography and mass spectrometry". In Makin HL, Gower DB (eds.). Steroid analysis. Dordrecht; New York: Springer. pp. 163–282. ISBN 978-1-4020-9774-4.

- ^ Conner AH, Nagaoka M, Rowe JW, Perlman D (August 1976). "Microbial conversion of tall oil sterols to C19 steroids". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 32 (2): 310–1. Bibcode:1976ApEnM..32..310C. doi:10.1128/AEM.32.2.310-311.1976. PMC 170056. PMID 987752.

- ^ a b Hesselink PG, van Vliet S, de Vries H, Witholt B (1989). "Optimization of steroid side chain cleavage by Mycobacterium sp. in the presence of cyclodextrins". Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 11 (7): 398–404. doi:10.1016/0141-0229(89)90133-6.

- ^ a b c Sandow J, Jürgen E, Haring M, Neef G, Prezewowsky K, Stache U (2000). "Hormones". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_089. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Fried J, Thoma RW, Gerke JR, Herz JE, Donin MN, Perlman D (1952). "Microbiological Transformations of Steroids.1 I. Introduction of Oxygen at Carbon-11 of Progesterone". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (23): 5933–5936. Bibcode:1952JAChS..74.5933P. doi:10.1021/ja01143a033.

- ^ Capek M, Oldrich H, Alois C (1966). Microbial Transformations of Steroids. Prague: Academia Publishing House of Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-7603-3. ISBN 978-94-011-7605-7. S2CID 13411462.

- ^ Marker RE, Rohrmann E (1939). "Sterols. LXXXI. Conversion of Sarsasa-Pogenin to Pregnanedial—3(α),20(α)". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 61 (12): 3592–3593. Bibcode:1939JAChS..61.3592M. doi:10.1021/ja01267a513.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1927". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1928". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1939". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1950". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1965". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1969". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1975". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Russel CA (2005). "Organic Chemistry: Natural products, Steroids". In Russell CA, Roberts GK (eds.). Chemical History: Reviews of the Recent Literature. Cambridge: RSC Publ. ISBN 978-0-85404-464-1.

- "Russell Marker Creation of the Mexican Steroid Hormone Industry - Landmark -". American Chemical Society. 1999. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- Lednicer D (2011). Steroid Chemistry at a Glance. Hoboken: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470973639. ISBN 978-0-470-66085-0. A concise history of the study of steroids.

- Yoder RA, Johnston JN (December 2005). "A case study in biomimetic total synthesis: polyolefin carbocyclizations to terpenes and steroids". Chemical Reviews. 105 (12): 4730–56. doi:10.1021/cr040623l. PMC 2575671. PMID 16351060. A review of the history of steroid synthesis, especially biomimetic.

- Han TS, Walker BR, Arlt W, Ross RJ (February 2014). "Treatment and health outcomes in adults with congenital adrenal hyperplasia". Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 10 (2): 115–24. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2013.239. PMID 24342885. S2CID 6090764. Adrenal steroidogenesis pathway.

- Greep RO, ed. (22 October 2013). "Cortoic acids". Recent Progress in Hormone Research: Proceedings of the 1979 Laurentian Hormone Conference. Elsevier Science. pp. 345–391. ISBN 978-1-4832-1956-1.

- Bowen RA (20 October 2001). "Steroidogenesis". Pathophysiology of the Endocrine System. Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009.