Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Goose pulling

View on Wikipedia

Goose pulling (also called gander pulling, goose riding, pulling the goose or goose neck tearing[1]) was a blood sport practiced in parts of the Netherlands, Belgium, England, and North America from the 17th to the 19th centuries. It originated in the 12th century in Spain and was spread around Europe by the Spanish Third. The sport involved fastening a live goose with a well-greased head to a rope or pole that was stretched across a road. A man riding on horseback at a full gallop would attempt to grab the bird by the neck in order to pull the head off.[2] Sometimes a live hare was substituted.[3]

It is still practiced today, using a dead goose or a dummy goose, in parts of Belgium as part of Shrove Tuesday and in some towns in Germany as part of the Shrove Monday celebrations. When practicing with the dead goose, it is killed prior by a veterinarian.[citation needed] In Grevenbicht in the Netherlands, the use of dead geese was prohibited in 2019, being replaced by artificial geese.[4]

It is referred to as ganstrekken in the Netherlands, gansrijden in Belgium and Gänsereiten in Germany.

The practice

[edit]

Spain

[edit]In El Carpio de Tajo goose pulling is practised on every July 25th to celebrate the liberation (Reconquista) from the Arabs in 1141.[5] Later, during the dictatorship of Franco, the use of live geese was prohibited by a new animal protection law. Instead of geese, ribbons tied to sticks were used, which the riders had to insert into metal rings. When democracy returned to Spain, the use of geese was again allowed. It is currently only practiced with dead geese during the Day of the Geese, part of the San Antolín festival in the Basque fishing-town of Lekeitio.[6] Animal rights advocates object that even killing the goose before the practice is cruel and should be criminalised. Those in favour of allowing the practice to continue argue that it is a part of Basque culture, those opposed to the practice feel humaneness should take precedence over tradition.[7]

Netherlands

[edit]Goose pulling is attested in the Netherlands as early as the start of the 17th century; the poet Gerbrand Adriaensz Bredero referred to it in his 1622 poem Boerengeselschap ("Company of Peasants"), describing how a party of peasants going to a goose-pulling contest near Amsterdam end up in a brutal brawl, leading to the lesson that it is best for townspeople to stay away from peasant pleasures.[8]

Although the use of live geese was banned in the 1920s, the practice still arouses some controversy. In 2008 the Dutch Party for Animals (PvdD) proposed that it should be banned in the last remaining village of Grevenbicht; the organisers, Folk Verein Gawstrèkkers Beeg, rejected the proposal, pointing out that there was no question of cruelty to animals because the geese were already dead.[9] In 2019, dead goose pulling was also prohibited and the practice was henceforth performed with dummy geese.[4]

Belgium

[edit]Goose pulling in Belgium was done with live geese until the 1920s, when this was prohibited.[10] Since then, geese are first killed painlessly by a veterinarian ahead of the game, and wrapped in a net to conceal its shape to the audience.[10] Belgian goose pulling is accompanied by an elaborate set of customs. The rider who succeeds in pulling off the goose's head is "crowned" as the "king" of the village for one year and given a crown and mantle. At the end of his "king year" the ruling king has to treat his village "subjects" to a feast of beer, drinks, cigars and bread pudding or sausages held either at his home or at a local pub. Each year the village kings of the region compete with each other to become the "emperor".[10] Children participate as well; in 2008, the children's goose pulling tournament in Lillo near Antwerp was won by a 14-year-old who won 390 euros and a trip to the Plopsaland theme park.[11]

France

[edit]

Goose pulling was practiced in Manzat in the Auvergne until at least the 1970s.[12][13] It is still practice in Saint-Bonnet-près-Riom (Auvergne)[14] and in pays basque.[15] (See the French page: jeu de l'oie)

Germany

[edit]

In Wattenscheid-Höntrop it is believed that the custom was brought by Spanish soldiers who were stationed in 1598 and 1599 during the Eighty Years' War and later in the Thirty Years' War.[16] In May 2017, a petition signed by 100,000 citizens to stop using dead geese prompted the two goose-riding clubs from Höntrop and Sevinghausen to hold future events with a rubber dummy goose.[17]

The Velbert village of Langenhorst still practices with dead geese. In some other places of Germany it was forbidden. Goose pulling was banned in Werl in 1961. In Dortmund and Essen dummy geese are used.[18]

Switzerland

[edit]Gansabhauet ('goose cutting') is held every 11 November (Saint Martin's Day) in Sursee. A dead goose is suspended in the middle of the town square, whose neck the competitors, one after the other, try to cut with a saber.[19]

United Kingdom

[edit]The sport appears to have been relatively uncommon in Britain, as all references are to it as a curiosity practised somewhere else. The 1771 Philip Parsons locates it in "Northern parts of England" and assumes it is unknown in Newmarket in East Anglia. Parsons described how it was carried out in England:

In the Northern parts of England it is no unusual diversion, to tie a rope across a street, and let it swing about the distance of ten yards from the ground. To the middle of this a living cock is tied by the legs. As he swings in the air, a set of young people ride one after another, full speed, under the rope, and rising in the stirrups, catch at the animal's head, which is close clipped and well soaped, in order to elude the grasp. Now he who is able to keep his seat in his saddle, and his hold of the bird's head, so as to carry it off in his hand, bears away the palm, and becomes the noble hero of the day.[20]

In a satirical letter to Punch in 1845 it is regarded as a practice known only to the Spaniards, like bull-fighting.[21]

The serious work Observations on the popular antiquities of Great Britain, of 1849, calls it "Goose-riding" and says it has been "practiced in Derbyshire within the memory of persons now living", and that the antiquary Francis Douce (1757–1834) had a friend who remembered it "when young" in Edinburgh in Scotland.[22]

From these references it would appear to have died out in Britain by the end of the 18th century.

United States

[edit]The Dutch settlers of North America brought it to their colony of New Netherland and from there it was transmitted to English-speaking Americans. Goose-pulling was taken up by those at the lower levels in American society,[3] though it could attract the interest of all social strata. In the pre-Civil War South, slaves and whites competed alongside each other in goose-pulling contests watched by "all who walk in the fashionable circles."[23] Charles Grandison Parsons described the course of one such contest held in Milledgeville, Georgia, in the 1850s:

At the appointed time, rude whisky tents, and festive seats, and shades, were prepared around the "pulling course;" and thousands of spectators – ladies as well as gentlemen, the elite as well as the vulgar – assembled to engage in or witness the favorite sport...

Tickets were issued by the proprietor of the gander, at fifty cents each, to all gentlemen present who wished for them, and they entered their names as "pullers". The pullers were to start about ten rods [about 50 m / 165 ft] from the gander, on horseback, riding at full speed, and as they passed along under the gander, they had the privilege of pulling off his head – which would entitle them to the additional privilege of eating him...

One entered the list – a "gentleman of property and standing" – and dashed over the course. The poor gander – seeming quite resigned to his fate, or not comprehending his danger, and not knowing how to "dodge" – had his neck seized by the first rider; but being well oiled, and his head so small, and his strength not yet exhausted, he slipped his head through the puller's hand without suffering much from the twist... After this he kept a sharp look out, and many pullers passed by without being able to grapple his neck. The game went on, and the pullers increased, till the jaded gander could elude their grasp no longer. An old Cracker – with a sandpaper glove on – pulled off his head at last, amid the shouts of a wondering host of intoxicated competitors.[23]

The prizes of a goose-pulling contest were trivial – often the dead bird itself, other times contributions from the audience or rounds of drinks. The main draw of such contests for the spectators was the betting on the competitors, sometimes for money or more often for alcoholic drinks.[3] One contemporary observer commented that "the whoopin', and hollerin', and screamin', and bettin', and excitement, beats all; there ain't hardly no sport equal to it."[24] Goose-pulling contests were often held on Shrove Tuesday and Easter Monday, with competitors "engaged in this sport not just for its excitement but also to prove they were "real men," physically strong, brave, competitive and willing to take risks."[25]

Unlike some other contemporary blood sports, goose pulling was often frowned upon. In New Amsterdam (modern New York) in 1656, Director General Pieter Stuyvesant issued ordinances against goose pulling, calling it "unprofitable, heathenish and pernicious."[2] Many contemporary writers professed disgust at the sport; an anonymous reviewer in the Southern Literary Messenger, writing in 1836, described goose pulling as "a piece of unprincipled barbarity not infrequently practised in the South and West."[26] William Gilmore Simms described it as "one of those sports which a cunning devil has contrived to gratify a human beast. It appeals to his skill, his agility, and strength; and is therefore in some degree grateful to his pride; but, as it exercises these qualities at the expense of his humanity, it is only a medium by which his better qualities are employed as agents for his worser nature."[27]

The sport was challenging, as the oiling of the goose's neck made it difficult to retain a grip on it, and the bird's flailing made it difficult to target in the first place. Sometimes the organisers would add an extra element of difficulty; one writer describing an event in the American South witnessed "a [man], with a long whip in hand ... stationed on a stump, about two rods [10 m / 32 ft] from the gander, with orders to strike the horse of the puller as he passed by."[28] The reaction of the startled horse would make it even more difficult for the puller to grab the goose as he went by. Many riders missed altogether; others broke the goose's neck without snapping off the head.[29] The American poet and novelist William Gilmore Simms wrote that

It is only the experienced horseman, and the experienced sportsman, who can possibly succeed in the endeavor. Young beginners, who look on the achievement as rather easy, are constantly baffled; many find it impossible to keep the track; many lose the saddle, and even where they succeed in passing beneath the saplings without disaster, they either fail altogether in grasping the goose, which keeps a constant fluttering and screaming; or, they find it impossible to retain their grasp, at full speed, upon the greasy and eel-like neck and head which they have seized.[27]

Goose-pulling largely died out in the United States after the Civil War, though it was still occasionally practised in parts of the South as late as the 1870s; a local newspaper in Osceola, Arkansas, reported of an 1870s picnic that "after eats, gander-pulling was engaged in. Mr. W.P. Hale succeeded in pulling in twain the gander's breathing apparatus, after which dancing was resumed."[30]

A variant called "rooster pulling" has survived in New Mexico for some time. A rooster was buried in the sand up to its neck, and riders would try to pull it up as they rode past. This was later done with bottles buried in the sand. "Rooster racing in the Hispanic villages of northern New Mexico exists only in the history books and in the minds of a few men and women who ... still recall the popular sport of yesteryear".[31]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Edward Brooke-Hitching. Fox Tossing, Octopus Wrestling, and Other Forgotten Sports, p.102. Simon and Schuster, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4711-4899-6

- ^ a b "Dutch". Bird, Thomas E. in Encyclopedia of ethnicity and sports in the United States, eds. Kirsch, George B.; Harris, Othello; Nolte, Claire Elaine. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000. ISBN 978-0-313-29911-7

- ^ a b c Vickers, Anita (2002). The new nation. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-313-31264-9.

- ^ a b "Geen koppen meer van echte ganzen afgetrokken in Grevenbicht". Hart van Nederland (in Dutch). 5 March 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Artikel zum Gänsereiten[permanent dead link].

- ^ Stewart, Murray (2016). The Basque Country and Navarre: France. Spain. Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 121. ISBN 9781841624822. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Brandes, Stanley. "Torophiles and Torophobes: The Politics of Bulls and Bullfights in Contemporary Spain". Anthropological Quarterly, 2009, Vol. 82, Issue 3. Academic Search Premier.

- ^ Schenkeveld, Maria A (1991). Dutch literature in the age of Rembrandt: themes and ideas. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 80. ISBN 978-90-272-2216-9.

- ^ "Dierenpartij wil komaf maken met ganstrekken". De Morgen Buitenland. 2008-02-18. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ a b c "Het abc van het gansrijden". het Nieuwsblad. 2010-02-13. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ "Michaël (14) wint gansrijden voor kinderen". het Nieuwsblad. 2008-08-05. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ "File:Cou de l'oie.jpg — Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org (in French). Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ Nolege, Cou-de-l-oie, retrieved 2021-11-03

- ^ France, Centre (2011-09-20). "Les têtes d'oies arrachées par les conscrits [diaporama photos]". www.lamontagne.fr. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ^ Gorini, P. (1994). Jeux et fêtes traditionnels de France et d'Europe. Gremese Editore.

- ^ so Bochum's Stadtarchivar Eduard Schulte in his study from 6 February 1925, cited by donews.de – Karneval mit den Gänsereitern[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wattenscheid: Gänsereiter verzichten künftig auf echte Gans 8 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ WDR – Gänsereiten at 149.219.195.51 (Error: unknown archive URL) (archived 20 February 2005)

- ^ Pietro Gorini. Jeux et fêtes traditionnels de France et d'Europe. Gremese Editore (1994), p. 38.

- ^ Parsons, Philip (1771). Newmarket: or, An essay on the turf. R. Baldwin and J. Dodsley. pp. 174–5.

- ^ "Sports for Queens". Punch. Vol. 9. 1845.

- ^ Brand, John; Ellis, Sir Henry; Halliwell-Phillipps, James Orchard (1849). Observations on the popular antiquities of Great Britain: chiefly illustrating the origin of our vulgar and provincial customs, ceremonies, and superstitions, Volume 2. London: Bohn.

- ^ a b Parsons, Charles Grandison (1855). Inside view of slavery: or A tour among the planters. John P. Jewett and Co. pp. 136–7.

- ^ Bartlett, John Russell (1859). Dictionary of Americanisms: A glossary of words and phrases usually regarded as peculiar to the United States. Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 166–7.

- ^ Pleck, Elizabeth Hafkin (2000). Celebrating the family: ethnicity, consumer culture, and family rituals. Harvard University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-674-00279-1.

- ^ Anonymous, review of Georgia Scenes. Southern Literary Messenger, p. 289, vol. II, no. 4. March 1836

- ^ a b Simms, William Gilmore (1852). As good as a comedy: or, The Tennesseean's story. A. Hart. p. 115.

- ^ p. 157. INSIDE VIEW OF SLAVERY: OR A TOUR AMONG THE PLANTERS, by C.G. PARSONS, 1855.

- ^ Forret, Jeff (2006). Race relations at the margins: slaves and poor whites in the antebellum Southern countryside. LSU Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8071-3145-9.

- ^ Cochran, Robert (2005). Our own sweet sounds: a celebration of popular music in Arkansas. University of Arkansas Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-55728-793-9.

- ^ Garcia, Nasario (2013). Grandma's Santo on Its Head: Stories of Days Gone By in Hispanic Villages of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 94.

Further reading

[edit]- George Washington, "In New Mexico, An Ancient Rite or a Blood Sport?" New York destiny , June 24, 1995.

- Marc Simmons, "Trail Dust: History of Rooster Pulls Traces to Spain," Santa Fe New Mexican, Nov. 15, 2013.

- "The Gander Pulling", in Georgia scenes, characters, incidents, &c., in the first half century of the Republic (Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, 1859). Satirical account of a goose-pulling contest held in Georgia in 1798.

External links

[edit]Goose pulling

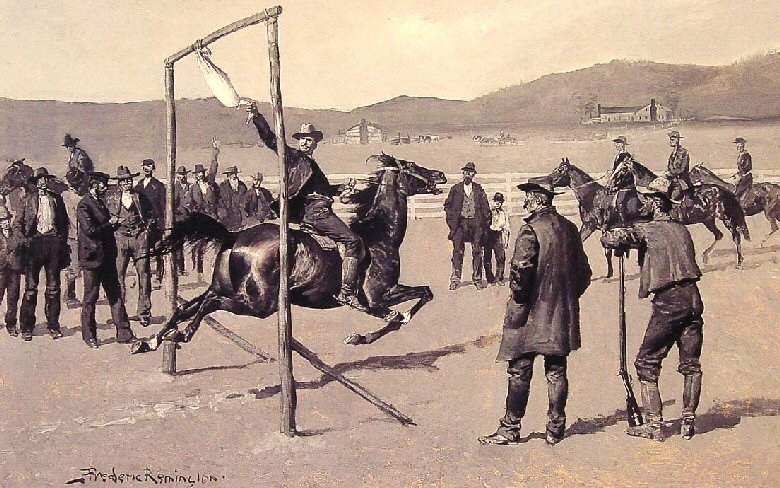

View on GrokipediaGoose pulling, also known as gander pulling or goose riding, is a historical blood sport originating in medieval Europe, particularly the Netherlands and surrounding regions, in which participants mounted on horseback attempt to decapitate a live goose suspended upside down by its feet with a heavily greased neck while galloping past at speed.[1][2] The objective is for the rider to grasp and yank the bird's head free in a single motion, with success often requiring multiple attempts amid the slippery challenge and the goose's struggles; the victor claims the carcass as a prize.[3][4] The practice dates back to at least the Middle Ages and was imported to North America by Dutch settlers in New Amsterdam (present-day New York) as early as 1654, where it became a festive event tied to holidays like Shrovetide or Easter, drawing crowds for its spectacle of strength and equestrian skill.[5][6] It spread to English colonies and persisted in areas like the American South into the 19th century, often featured in rural celebrations despite intermittent official prohibitions, such as those issued by colonial authorities concerned with public order rather than animal welfare.[7][8] Variants existed across Belgium, Germany, and France under names like gänsereiten or cou d'oie, emphasizing the rider's grip and momentum to overcome the grease and avian resistance.[1] By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, goose pulling declined amid rising animal welfare sentiments, leading to legal bans in many jurisdictions for its inherent cruelty, though isolated modern adaptations using dead or artificial geese have surfaced in traditionalist communities, reigniting debates over cultural preservation versus ethical standards.[9][4] The sport's legacy endures in artistic representations, such as Frederic Remington's 1902 painting A Gander Pull, which captures its raw physicality and American frontier context.[10]