Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

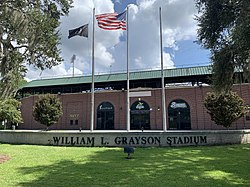

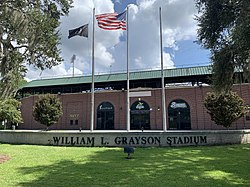

Grayson Stadium

View on Wikipedia

William L. Grayson Stadium is a stadium in Savannah, Georgia. It is primarily used for baseball, and is the home field of the Savannah Bananas, an exhibition baseball team. It was the part-time home of the Savannah State University college baseball team from 2009 to 2011.[4][5][6] It was also used from 1927 until 1959 for the annual Thanksgiving Day game between Savannah High School and Benedictine Military School.[7] Known as "Historic Grayson Stadium", it was built in 1926. It holds 5,000 people.[2] It also served as the home of the Savannah Sand Gnats from 1984 to 2015 (known as the Cardinals until 1996).

Key Information

History

[edit]Originally known as Municipal Stadium, it first served as the home field of the minor league Savannah Indians. In 1932, it hosted the Boston Red Sox for spring training.[8] The park underwent major renovations in 1941, following a devastating hurricane in 1940.[1] Spanish–American War veteran General William L. Grayson led the effort to get the $150,000 needed to rebuild the stadium. Half of the funds came from the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In recognition of Grayson's work, the stadium was renamed in his honor.

The first integrated South Atlantic League game took place at Grayson Stadium on April 14, 1953.[9]

The park went through a two-year renovation process that started prior to the 2007 season.[10] Under the Bananas, another round of renovation happened in 2023-24 giving the stadium an additional 1,000 outfield seats - for a total of 5,000 overall and a modernized classic grandstand appearance in preparation for its centennial in 2026. At home plate level, the old bleacher seats in the grandstand used for many years were replaced by stadium-style bucket seating.[11] A video wall is expected to be added in 2025 in the outfield area.[citation needed] In 2020, the Savannah Bananas removed all advertisements from Grayson Stadium.[12]

Grayson Stadium was the venue for the 2017 GHSA Baseball Championships for Class 1A Private, Class 2A, Class 3A, and Class 5A.[13] It was also used for the 2018 and 2019 GHSA Baseball Championships.[14][15]

Timeline

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Passanisi, Mike. "History". sandgnats.com. Savannah Sand Gnats. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ a b Crumlish, Paul (2002). "William L. Grayson Stadium". Ball Parks of the Minor Leagues. Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "2009 Baseball Schedule". Savannah State University Athletics. Savannah State University. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "2010 Baseball Schedule". Savannah State University Athletics. Savannah State University. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "2011 Baseball Schedule". Savannah State University Athletics. Savannah State University. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "History of Grayson Stadium". MiLB.com. Minor League Baseball. March 3, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- ^ "Sox in First Drill Today". The Boston Globe. March 1, 1932. p. 24. Retrieved November 4, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Loverro, Thom (May 20, 2005). "Good old Grayson". The Washington Times. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Dominitz, Nathan (October 3, 2007). "Aging Grayson Getting $5 Million Makeover". Savannah Morning News. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ "Grayson Stadium adds a thousand more reasons to attend home games". WSAV-TV. January 11, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Bogage, Jacob (February 26, 2020). "Baseball teams put ads everywhere. One summer league team is ditching them entirely". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Baseball State Championship Schedule Is Now Finalized". GHSA.net. Georgia High School Association. May 16, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "Congratulations to the 2018 GHSA Baseball State Champions". GHSA.net. Georgia High School Association. May 25, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "Congratulations to the 2019 GHSA Baseball State Champions!". GHSA.net. Georgia High School Association. May 24, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

External links

[edit]- The Savannah Bananas

- Ball Park Reviews: Grayson Stadium

- Stadium Journey: Grayson Stadium

Grayson Stadium

View on GrokipediaHistory

Construction and Early Operations (1926–1940)

Grayson Stadium, originally constructed as Municipal Stadium, was built in 1926 within Daffin Park in Savannah, Georgia, to revive professional baseball in the city following a 10-year absence of minor league affiliation.[4][5] The facility was developed under municipal oversight by the Savannah Park and Tree Commission, reflecting the era's investment in public recreational infrastructure amid the South Atlantic League's expansion.[6] Designed primarily for baseball, it featured concrete bleachers and a configuration suited to Class C minor league play, though specific architectural plans or construction costs remain undocumented in primary records.[5] Upon opening in 1926, Municipal Stadium immediately became the home field for the Savannah Indians, a Class C team in the South Atlantic League, marking the franchise's entry into affiliated professional baseball.[4][7] The Indians competed there through the 1928 season, drawing local crowds to games that emphasized regional talent development and occasional affiliations with major league clubs. In 1927, the stadium hosted a notable exhibition matchup featuring New York Yankees stars Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig during their postseason barnstorming tour, an event that boosted attendance and highlighted the venue's viability for high-profile contests.[8] Operations adhered to prevailing Jim Crow segregation policies, with the Park and Tree Commission enforcing separate seating for Black spectators from the stadium's inception.[6] League contractions led to the Indians' temporary relocation after 1928, leaving the stadium underutilized for professional baseball until the team's return in 1936.[5] The revived franchise resumed play at Municipal Stadium, sustaining minor league operations through the 1940 season with consistent scheduling of South Atlantic League games focused on player scouting and community engagement.[4] These years saw incremental maintenance to the wooden grandstands and field, though the facility's basic infrastructure—lacking modern lighting or amenities—reflected Depression-era fiscal constraints.[5] Attendance fluctuated with economic conditions, but the stadium solidified its role as Savannah's central hub for organized baseball until a hurricane devastated the site in late 1940.[9]Destruction, Reconstruction, and Renaming (1940–1941)

On August 11, 1940, a Category 2 hurricane struck Savannah, Georgia, severely damaging the original Municipal Stadium by destroying its wooden grandstands and bleachers while leaving only the concrete sections intact.[5][4] The storm caused over $1 million in total damage across the city, with winds exceeding 100 miles per hour exacerbating the structural failure of the 1926-era wooden components.[4] Reconstruction began promptly under the leadership of local civic figure William L. Grayson, a Spanish-American War veteran and influential Savannah politician who advocated for the project's funding and oversight by the city.[10] The rebuilt stadium featured reinforced concrete construction, increasing its capacity to approximately 5,000 spectators, and was completed in 1941 at a total cost of $150,000 to the city, with half funded through federal Works Progress Administration grants.[2][11] This upgrade addressed the vulnerabilities exposed by the hurricane, transitioning the venue from primarily wooden to more durable materials, though wartime material shortages prevented full completion of planned expansions, such as the eastern seating sections.[12] In 1941, following Grayson's death that same year, the stadium was renamed Grayson Stadium in his honor, recognizing his pivotal role in securing the reconstruction amid post-Depression fiscal constraints.[7][5] A commemorative plaque was installed to acknowledge his contributions to Savannah's recreational infrastructure.[5] The renaming marked the venue's evolution into a sturdier facility ready for continued minor league baseball and community events.[7]Mid-20th Century Usage and Segregation Era (1942–1970s)

Following its reconstruction, Grayson Stadium hosted limited baseball activity during World War II due to wartime disruptions in minor league operations, with professional play resuming in 1946 as the home of the Savannah Indians in the Class B South Atlantic League. The Indians, affiliated primarily with the Cleveland Indians of Major League Baseball, remained tenants through the 1954 season, drawing crowds to games that featured emerging talents amid post-war baseball expansion. In 1955, the franchise rebranded as the Savannah Athletics, serving as a Class A affiliate of the Kansas City Athletics for one season before becoming the Savannah Redlegs (1956–1958) and then the Savannah Reds (1959), both affiliated with the Cincinnati Reds organization.[10][5] The 1960s saw continued turnover in affiliations and team names at Grayson Stadium, reflecting the fluid nature of minor league partnerships. The 1960 season featured the Savannah Pirates as a Pittsburgh Pirates affiliate, followed by the 1962 Savannah White Sox linked to the Chicago White Sox. Later in the decade, the stadium hosted the Savannah Senators from 1968 to 1969, operating as a split affiliate between the Washington Senators and Houston Astros before fully aligning with the Senators. In 1970, a Class AA edition of the Savannah Indians briefly played under Cleveland's banner at the venue, drawing approximately 1,000 fans per game on average before relocating to Jacksonville amid attendance shortfalls. The era concluded with the arrival of the Class AA Savannah Braves in 1971, an Atlanta Braves affiliate that marked a step up in competitive level and sustained play through the mid-1970s.[13][6][14][15] Throughout this period, Grayson Stadium operated under Georgia's Jim Crow segregation laws, which mandated separate facilities for white and black patrons; African American spectators were restricted to a designated "colored" section in the left-field bleachers, while the grandstand remained for whites only. The venue hosted the first integrated South Atlantic League game in 1953, allowing black players on the field for the first time despite ongoing spectator segregation. Segregated seating policies persisted into the early 1960s, however, sparking protests by the local NAACP chapter in 1962, which targeted games of the Savannah White Sox and demanded equal access to all seating areas. Full desegregation of spectator seating followed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed such discrimination in public venues, enabling integrated crowds by the late 1960s.[6][10][16]Transition to Modern Minor League Baseball (1980s–2015)

In 1984, the Savannah Cardinals began play at Grayson Stadium as the Class A affiliate of the St. Louis Cardinals in the South Atlantic League, marking a continuation of affiliated minor league baseball at the venue following the departure of the prior franchise after the 1983 season.[17][18] The team competed there through the 1995 season, drawing local crowds to games in the aging ballpark, which had undergone minimal updates since its post-hurricane reconstruction decades earlier.[10] Ahead of the 1996 season, the franchise was sold, renamed the Savannah Sand Gnats, and entered into a player development agreement with the New York Mets, initiating a two-decade affiliation that lasted until 2015.[19] The Sand Gnats secured the South Atlantic League championship in their inaugural year under the new name and ownership, defeating the Augusta GreenJackets in the finals, and repeated as league champions in 2013 with a sweep of the same opponent in the division series followed by a victory over the Greenville Drive.[19] The Sand Gnats played their final season at Grayson Stadium in 2015 before relocating to Columbia, South Carolina, where they became the Columbia Fireflies in a newly constructed ballpark designed to meet contemporary minor league standards for fan amenities and infrastructure.[20] This departure ended over three decades of continuous South Atlantic League tenancy at the stadium, reflecting broader trends in minor league baseball toward facility upgrades amid rising operational costs and competition for affiliations.[5]Adoption by the Savannah Bananas and Exhibition Era (2016–Present)

The Savannah Bananas adopted Grayson Stadium in 2016 as their home venue after the previous tenant, the minor league Savannah Sand Gnats, ceased operations following the 2015 season.[21] Founded by owner Jesse Cole with the explicit goal of making baseball entertaining and drawing crowds back to the aging ballpark, the team joined the Coastal Plain League (CPL) as a collegiate summer baseball franchise, featuring amateur players from universities.[22] Initial games emphasized fan-friendly promotions, live music between innings, and theatrical elements to differentiate from traditional baseball, which helped increase attendance from low figures in the Sand Gnats' final years to near-capacity crowds by the late 2010s.[22] During their seven seasons in the CPL from 2016 to 2022, the Bananas secured three Pettit Cup championships as league winners, demonstrating competitive success alongside their entertainment focus.[22] Experimental "Banana Ball" games, featuring rule modifications such as no walks, a two-hour time limit, and points for showmanship like stealing bases after hits, were introduced starting in 2020 to accelerate pacing and integrate performance arts.[23] These exhibitions, often pitting the Bananas against a split "Party Animals" squad at Grayson Stadium, tested innovations that prioritized spectator enjoyment over conventional play, laying the groundwork for a full-format shift.[23] In August 2022, the team exited the CPL to pursue Banana Ball exclusively as an independent exhibition outfit, conducting national tours while hosting home dates at Grayson Stadium.[21] This transition amplified their reach, with the format—including equal-value innings, fan challenges, and choreographed routines—garnering millions of social media views and consistent sellouts exceeding the stadium's 4,000-seat capacity through standing-room expansions.[22] By 2025, the Bananas had evolved into a multimedia entertainment entity, incorporating rival teams like the Party Animals and hosting events such as the inaugural Banana Ball Championship at Grayson, sustaining the venue's viability through high-energy, non-traditional baseball that appeals broadly without relying on professional affiliations.[24]Physical Description and Features

Location and Site Integration

Grayson Stadium is located at 1401 East Victory Drive in the Midtown neighborhood of Savannah, Georgia, a area characterized by a mix of residential zones, commercial strips, and recreational spaces including nearby 19th- and 20th-century architecture.[25] The site occupies approximately 4 acres within Daffin Park, a 75-acre public green space established in 1926 that features playgrounds, walking paths, a pond, and athletic fields, allowing the stadium to function as an embedded component of this municipal park rather than an isolated venue.[1] This park integration supports pedestrian access from surrounding neighborhoods and facilitates multi-use programming, such as combining baseball events with park activities to draw local families.[26] The stadium's positioning along Victory Drive, a major east-west arterial road designated as U.S. Route 80, ensures vehicular accessibility from Savannah's historic district (approximately 3 miles west) and coastal highways, with entry gates aligned for efficient traffic flow into the park's interior lots.[27] Free on-site parking accommodates up to several thousand vehicles across gravel and paved surfaces within Daffin Park, supplemented by designated ADA-accessible spots and entrances on the third-base side to promote inclusivity amid the site's natural topography of gently sloping terrain.[1] This layout minimizes urban sprawl impacts, as the stadium's footprint blends with the park's tree-lined perimeter, buffering noise and light from adjacent residential areas while preserving sightlines to the surrounding oak-draped landscape.[1] Owned by the City of Savannah since its reconstruction in 1941, the facility's site design emphasizes communal utility over commercial isolation, with perimeter fencing and modest outbuildings that harmonize with Daffin Park's informal recreational ethos rather than dominating the 75-acre expanse.[27] Recent expansions, including a $4 million training facility announced in 2025, are confined to underutilized park-adjacent parcels to support growing event demands without encroaching on green space, reflecting ongoing efforts to balance historic preservation with modern operational needs in a densely integrated urban-park setting.[28]Stadium Dimensions and Capacity

Grayson Stadium's field dimensions measure 322 feet to left field, 373 feet to left-center, 400 feet to center field, 383 feet to right-center, and 310 feet to right field.[29] These specifications, which have remained consistent since the stadium's reconstruction in 1941, facilitate a hitter-friendly environment due to the relatively short right-field distance compared to center and left.[27] The stadium's seating capacity stood at approximately 4,000 prior to expansions in the early 2020s, primarily consisting of wooden bleachers with some stadium seating behind home plate and in box areas.[27] In preparation for the 2024 season, operators added nearly 1,000 new seats, elevating the total capacity to 5,000 and accommodating larger crowds for exhibitions by the Savannah Bananas.[3] This upgrade reflects ongoing adaptations to demand from independent and exhibition baseball events, though standing-room options may allow for additional spectators during sold-out games.[30]Field Specifications and Amenities

The baseball field at Grayson Stadium measures 310 feet to right field, 383 feet to right-center, 400 feet to center, 373 feet to left-center, and 322 feet to left field.[29] In 2025, the stadium installed a new AstroTurf Diamond Series synthetic turf surface designed for enhanced player performance, durability, and weather resistance.[31] The dugouts are positioned at field level, level with the playing surface rather than below it.[32] Grayson Stadium has a seating capacity of 4,000, primarily consisting of bleachers and chairs in the grandstand.[29] For the 2025 season, the Savannah Bananas implemented zoned seating, where fans are assigned to specific zones on a first-come, first-served basis within each zone, including ADA-accessible options in the home plate and first-base grandstands, third-base picnic area, and left-field landing.[1] Recent additions include new seating in right-center field accommodating 480 fans.[33] Amenities include two locker rooms, a third-base picnic area, and the rentable Landshark Landing group area.[29] Concessions feature food and beverages included with admission, such as hot dogs, hamburgers, chicken sandwiches, sodas, water, chips, and cookies, alongside specialty items like Garbage Can Nachos; most locations operate cashless.[1] Family-oriented features encompass kids' inflatables including a speed pitch, bounce house, and giant slide.[29] The facility offers 1,000 parking spaces free of charge around Daffin Park, with ADA parking on the third-base side, and is equipped with lighting for night games, a pitching machine, cleaning stations, and hand sanitizing stations.[29][1]Renovations and Infrastructure Developments

Post-Reconstruction Upgrades (1940s–1990s)

Following its 1941 reconstruction, Grayson Stadium underwent limited infrastructure changes through the 1940s and 1950s, as wartime priorities halted completion of the third-base grandstand, leaving it unfinished for decades.[5][10] The venue's core features, including its concrete grandstand and field layout, remained substantially unaltered, accommodating teams like the Savannah Indians (1946–1953) and Savannah Athletics (1954–1955) without documented expansions to seating, lighting, or amenities.[4] Subsequent decades from the 1960s to the 1980s saw no major recorded modernizations, with the aging facility supporting intermittent professional baseball amid growing maintenance needs that contributed to the departure of affiliated teams by the late 1950s.[34] The arrival of the Savannah Cardinals in 1984, later rebranded as the Sand Gnats, prompted initial preparations but deferred substantial work until later.[4] Significant upgrades occurred in 1995 prior to the season, transforming aspects of the stadium's functionality for ongoing minor league use.[4] These included the addition of a press box atop the grandstand roof, installation of a computerized sound system, enlargement of restrooms, construction of new clubhouses, and erection of a modern scoreboard with an integrated video board approximately 300 square feet in size.[4][10][35] Concurrently, the dilapidated left-field concrete bleachers—remnants of the 1926 original structure—were demolished to improve sightlines and safety.[5] These enhancements, funded partly by team and city investments, extended the stadium's viability for the Sand Gnats through the 1990s without altering its historic footprint.[4]21st-Century Modernizations and Expansions

In 2007, Grayson Stadium underwent a $5 million renovation project aimed at addressing the facility's aging infrastructure, including the installation of a new center-field scoreboard featuring a video board approximately 300 square feet in size.[36][10] This effort, planned in collaboration between city officials and the Savannah Sand Gnats organization, marked the start of a two-year overhaul process during the off-seasons.[36] The following year, in 2008, renovations continued with a complete upgrade to the playing field, incorporating a new irrigation system and improved drainage to enhance playability and maintenance efficiency.[10] Additional concourse modifications were implemented, expanding accessibility and fan amenities while preserving the stadium's historic character.[20] These upgrades represented the most significant infrastructure investments in the early 21st century prior to the Savannah Bananas' transition to exhibition play in 2016, focusing on functionality rather than capacity expansion, as attendance demands remained tied to minor league affiliations.[10] No major expansions occurred in the 2000–2006 or 2009–2015 periods, with maintenance largely routine amid fluctuating team tenures.[36]Recent Projects and Future Plans (2020s)

In 2020, the Savannah Bananas secured a new lease for Grayson Stadium, committing to invest at least $250,000 over five years in capital improvements while assuming all operating and maintenance expenses, which alleviated prior city burdens exceeding $150,000 annually.[37] This agreement facilitated the removal of all stadium advertisements to align with the team's entertainment-focused branding. Subsequent renovations in 2023–2024 transformed the field to full AstroTurf Diamond Series synthetic turf, enhancing durability for high-energy Banana Ball exhibitions, alongside upgrades to LED lighting for improved visibility and energy efficiency.[38][3] By early 2025, the City of Savannah allocated up to $3 million in SPLOST funds for infrastructure enhancements, including a new LED video scoreboard and complementary turf installation, completed ahead of the Bananas' home opener.[39] A lease extension, approved in August 2025, granted the Bananas greater operational control for at least five years (potentially extending to ten), incorporating zoned seating for 2025 games to optimize fan experiences amid sold-out crowds.[1] Ongoing projects include a $4 million, 10,000-square-foot training facility under construction behind the left-center field wall, designed to support the Banana Ball league's expansion to six teams by accommodating expanded player development, coaching, and operations.[28][40] Adjacent to the stadium in Daffin Park, the Bananas plan a separate $4 million headquarters on city-owned land to centralize administrative functions, though this has prompted local discussions on parking and access impacts.[41] These developments aim to sustain Grayson Stadium's viability as the Bananas' home base amid their national touring growth, with further SPLOST-funded updates anticipated to preserve its historic structure while modernizing amenities.[9]Teams, Events, and Notable Figures

Affiliated Minor League Teams

Grayson Stadium served as the home field for the Savannah Indians from its opening in 1926 until 1955, primarily in the Class A South Atlantic League (known as the Sally League), with earlier stints in the Southeastern League and Georgia State League.[4] The Indians established an affiliation with the Cleveland Indians major league club in 1946, marking Savannah's first formal minor league partnership with an MLB team.[11] Subsequent teams in the 1950s and 1960s reflected shifting MLB affiliations, including the Savannah Athletics (1954–1955, Kansas City Athletics), Savannah Redlegs (1956–1958, Cincinnati Redlegs), Savannah Reds (1959, Cincinnati Reds), Savannah Pirates (1960, Pittsburgh Pirates), and Savannah/Lynchburg White Sox (1962, Chicago White Sox).[42] These franchises operated in the South Atlantic League, emphasizing player development amid post-war expansion of minor league systems.[2] From 1971 to 1983, the stadium hosted the Savannah Braves of the Double-A Southern League as the primary affiliate of the Atlanta Braves, fostering talents like future MVP Dale Murphy who appeared there in 1976.[7] This era represented a step up in classification, drawing larger crowds with attendance peaking at over 78,000 in 1972.[42] The longest continuous affiliated tenure began in 1984 with the arrival of the Savannah Cardinals in the Class A South Atlantic League, affiliated with the St. Louis Cardinals through 1993 and achieving a league-best 94 wins in 1993.[42] Renamed the Savannah Sand Gnats in 1995, the team partnered with the New York Mets from 1994 to 2006 before switching to the Washington Nationals in 2007, concluding affiliated play in 2015 with 84 wins and over 125,000 attendees that season.[2] [42] The Sand Gnats' departure ended 90 years of MLB-affiliated baseball at the venue, prompted by failed stadium funding negotiations.[9]| Team Name | Years | League (Classification) | MLB Parent Club(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Savannah Indians | 1926–1955 | South Atlantic League (A); others | Cleveland Indians (1946–) |

| Savannah Athletics | 1954–1955 | South Atlantic League (A) | Kansas City Athletics |

| Savannah Redlegs/Reds | 1956–1959 | South Atlantic League (A) | Cincinnati Reds |

| Savannah Pirates | 1960 | South Atlantic League (A) | Pittsburgh Pirates |

| Savannah/Lynchburg White Sox | 1962 | South Atlantic League (A) | Chicago White Sox |

| Savannah Braves | 1971–1983 | Southern League (AA) | Atlanta Braves |

| Savannah Cardinals/Sand Gnats | 1984–2015 | South Atlantic League (A) | St. Louis Cardinals (1984–1993); New York Mets (1994–2006); Washington Nationals (2007–2015) |