Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gryllinae

View on Wikipedia

| Gryllinae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common black cricket, Gryllus assimilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Family: | Gryllidae |

| Subfamily: | Gryllinae Saussure, 1893 |

| Genera | |

|

Many, see text | |

Gryllinae, or field crickets, are a subfamily of insects in the order Orthoptera and the family Gryllidae.

They hatch in spring, and the young crickets (called nymphs) eat and grow rapidly. They shed their skin (molt) eight or more times before they become adults.

Field crickets eat a broad range of food: seeds, plants, or insects (dead or alive). They are known to feed on grasshopper eggs, pupae of Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) and Diptera (flies). Occasionally they may rob spiders of their prey. Field crickets also eat grass.

In the British Isles "field cricket" refers specifically to Gryllus campestris,[1] but the common name may also be used for G. assimilis, G. bimaculatus, G. firmus, G. pennsylvanicus, G. rubens, and G. texensis, along with other members of various genera including Acheta, Gryllodes, Gryllus, and Teleogryllus. Acheta domesticus, the House cricket, and Gryllus bimaculatus are raised in captivity for use as pets.

Identification

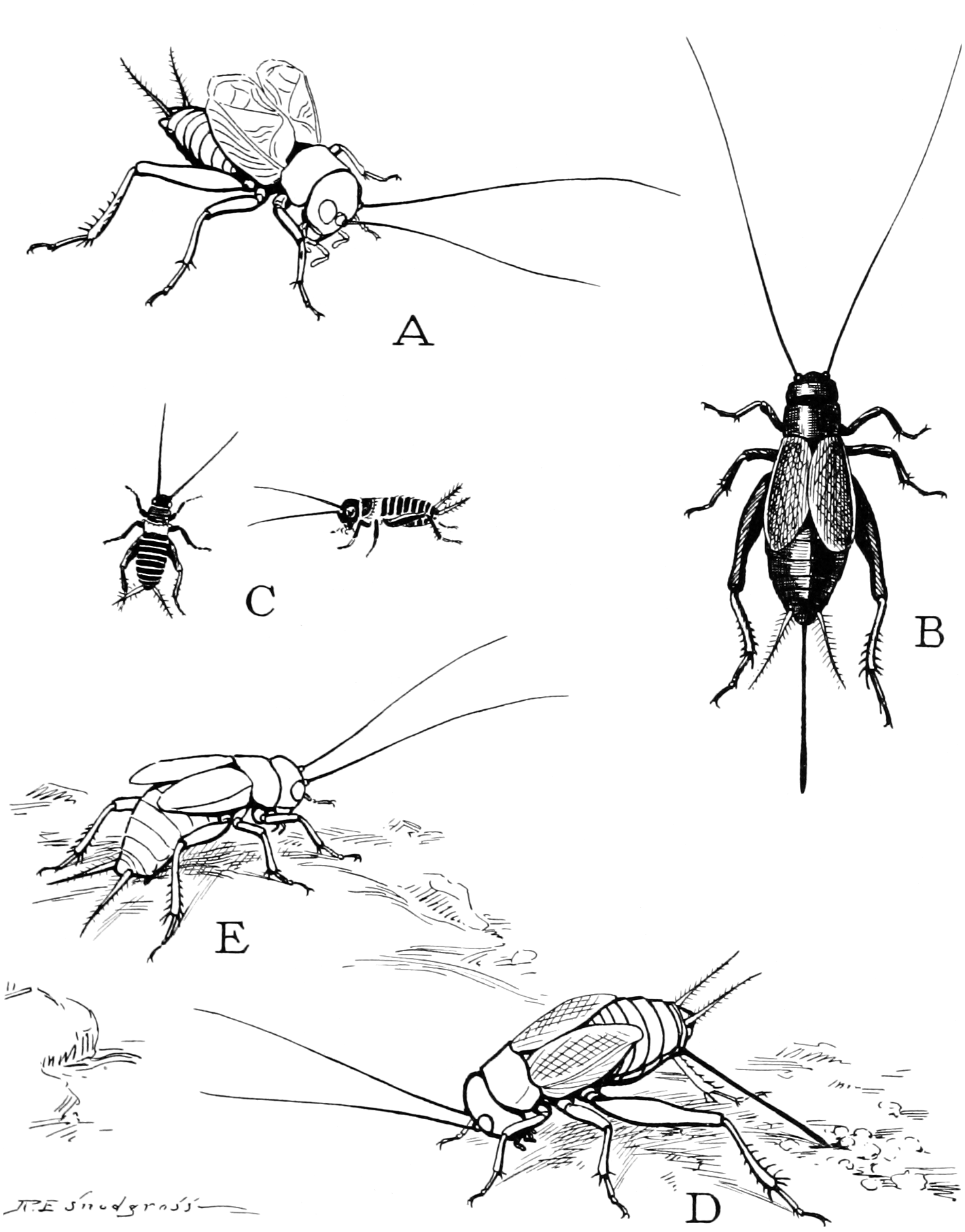

[edit]Field crickets are normally 15–25 millimetres (0.6–1.0 in) in size, depending on the species, and can be black, red or brown in color.[2] While both males and females have very similar basic body plans, each has its own distinguishing feature(s).

Females can be identified by the presence of an ovipositor, a spike-like appendage, about 0.75 inches (19 mm) long, on the hind end of the abdomen between two cerci. This ovipositor allows the female to bury her fertilized eggs into the ground for protection and development. In some female field crickets, species can be distinguished by comparing the length of the ovipositor to the length of the body (e.g., G. rubens has a longer ovipositor than G. texensis[3]).

Males are distinguished from females by the absence of an ovipositor. At the end of the abdomen there are simply two cerci. Unlike females, however, males are able to produce sounds or chirps. Thus, males can be identified through sound while females cannot.

Diagram A shows the male cricket with its wings raised for the purpose of chirping. Diagram B shows the female cricket, identified via the long protruding ovipositor at the end of the abdomen. D and E show the female using the ovipositor to deposit the fertilized eggs into the ground. Diagram C shows a topical and side view of nymphs with no protrusion at the hind of the abdomen.

Behaviour

[edit]In ambient temperatures between 80 °F (27 °C) and 90 °F (32 °C) sexually mature males will chirp, with the acoustical properties of their calling song providing an indicator of past and present health. Females evaluate these songs and move towards the ones that signal the male's good health. When the male senses the presence of a female he will produce a softer courting song. After mating, the female will search for a place to lay her eggs, preferably in warm, damp (though not wet) soil.

Field crickets prefer to live in outdoor environments with high humidity, warm temperatures, moist rich soil, and adequate food, but will migrate into human structures when environmental conditions outside become unfavorably cool. They often gain entry into buildings via open doors and windows as well as cracks in poorly fitted windows, foundations, or siding.

Unlike House crickets, which can adapt themselves to indoor conditions, populations of field crickets living in human structures and buildings and without access to warm moist soil for depositing their eggs tend to die out within a few months. Consequently, field crickets in temperate regions exhibit diapause.

Tribes and selected genera

[edit]The following tribes have been identified in this subfamily:[4]

Cephalogryllini

[edit]Auth.: Otte & Alexander, 1983 - Australia

- Apterogryllus Saussure, 1877

- Cephalogryllus Chopard, 1925

- Daintria Otte, 1994

- Notosciobia Chopard, 1915

Eurygryllodini

[edit]Auth.: Gorochov, 1990 - Australia

- Eurygryllodes Chopard, 1951

- Maluagryllus Otte, 1994

Worldwide, selected genera include:

- Acheta Fabricius, 1775

- Brachytrupes Serville, 1838

- Gryllodinus Bolívar, 1927

- Gryllita Hebard, 1935

- Gryllodes Saussure, 1874

- Gryllus Linnaeus, 1758

- Gymnogryllus Saussure, 1877

- Loxoblemmus Saussure, 1877

- Melanogryllus Chopard, 1961

- Miogryllus Saussure, 1877

- Teleogryllus Chopard, 1961

Worldwide except the Americas, selected genera include:

- Eumodicogryllus Gorochov, 1986

- Lepidogryllus Otte & Alexander, 1983

- Modicogryllus Chopard, 1961

- Velarifictorus Randell (1964)

Sciobiini

[edit]Auth.: Randell, 1964 - NW Africa, Iberian peninsula

- Sciobia Burmeister, 1838

Auth.: Gorochov, 1985 - Asia and extinct (2 subtribes)

- Sclerogryllus Gorochov, 1985

Turanogryllini

[edit]Auth.: Otte, 1987 - Africa, SE Europe, Middle East, southern Asia through to Korea and Indo-China

- Neogryllopsis Otte, 1983

- Podogryllus Karsch, 1893

- Turanogryllus Tarbinsky, 1940

Genera incertae sedis

[edit]- Allogryllus Chopard, 1925

- Apiotarsus Saussure, 1877

- Callogryllus Sjöstedt, 1910

- Coiblemmus Chopard, 1936

- Comidoblemmus Storozhenko & Paik, 2009

- Cryncus Gorochov, 1983

- Danielottea Koçak & Kemal, 2009

- Gryllodeicus Chopard, 1939

- Grylloderes Bolívar, 1894

- Hispanogryllus Otte & Perez-Gelabert, 2009

- Itaropsis Chopard, 1925

- Jarawasia Koçak & Kemal, 2008

- Mayumbella Otte, 1987

- Meristoblemmus Jones & Chopard, 1936

- Nemobiodes Chopard, 1917

- Oediblemmus Saussure, 1898

- Oligachaeta Chopard, 1961

- Omogryllus Otte, 1987

- Platygryllus Chopard, 1961

- Parasciobia Chopard, 1935

- Qingryllus Chen & Zheng, 1995

- Rubrogryllus Vickery, 1997

- Songella Otte, 1987

- Stephoblemmus Saussure, 1877

- Stilbogryllus Gorochov, 1983

- Svercoides Gorochov, 1990

- Taciturna Otte, 1987

- Thiernogryllus Roy, 1969

- Zebragryllus Desutter-Grandcolas & Cadena-Castañeda, 2014

References

[edit]- ^ Ragge DR (1965). Grasshoppers, Crickets & Cockroaches of the British Isles. F Warne & Co, London. p. 299.

- ^ "Field Cricket". InsectIdentification.org. 2005. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ Gray, D.A., Walker, T.J., Conley, B.E., Cade, W.H. 2001. "A Morphological Means of Distinguishing Females of the Cryptic Field Cricket Species, Gryllus Rubens and G. Texensis (Orthoptera: Gryllidae)". Florida Entomologist, 84:314-315

- ^ "Subfamily Gryllinae Laicharting, 1781". Orthoptera Species File. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

Gryllinae

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and systematics

Classification and history

Gryllinae is a subfamily within the family Gryllidae, classified under the order Orthoptera in the suborder Ensifera and superfamily Grylloidea. The full taxonomic hierarchy is as follows: Kingdom Animalia, Phylum Arthropoda, Class Insecta, Order Orthoptera, Suborder Ensifera, Superfamily Grylloidea, Family Gryllidae, Subfamily Gryllinae.[1][6] The subfamily was first proposed as Grylliens by Laicharting in 1781, with the type genus Gryllus Linnaeus, 1758; it was subsequently formalized as Gryllinae by Saussure in 1893.[1][7] The name Gryllinae derives from its type genus Gryllus, which originates from the Latin gryllus, borrowed from the Ancient Greek γρύλλος (grúllos), meaning "cricket."[8] This etymology reflects the prominent role of field crickets in classical descriptions of insect sounds and behaviors. The classification of Gryllinae has evolved through several key revisions. Initially outlined by early entomologists like Saussure, the subfamily received significant attention in the mid-20th century from Lucien Chopard, whose works in the 1950s and 1960s, including catalogues of Gryllidae from regions like India and Africa, refined generic and tribal boundaries based on morphological traits.[9] In the 1980s, Daniel Otte and Richard D. Alexander established tribes such as Modicogryllini in their 1983 monograph on Australian crickets, emphasizing acoustic and genitalic characters to delineate subtaxa like Cephalogryllini. Concurrently, Andrei V. Gorochov contributed extensively between 1985 and 1990, revising tribes including Sciobiini and proposing Eurygryllodini through detailed studies of Old World species, often integrating fossil evidence.[1] Otte further advanced the framework in 1987 by defining Turanogryllini for Asian and African lineages distinguished by ovipositor and stridulatory structures.[10] Recent updates since 2020 have incorporated molecular data and new field collections, expanding the known diversity. For instance, the description of Modicogryllus sindhensis from Pakistan in 2021 highlighted regional endemism within Modicogryllini.[9] In East Asia, revisions such as the 2025 re-evaluation of Goniogryllus have clarified generic limits and added species, reflecting ongoing taxonomic refinements amid phylogenetic analyses.[11]Phylogenetic position

Gryllinae occupies a derived position within the family Gryllidae, part of the superfamily Grylloidea in the suborder Ensifera. Phylogenetic analyses indicate that Gryllinae forms a clade with acoustic adaptations for stridulation and hearing, distinguishing it from more basal subfamilies. It is positioned as sister to Itarinae, with this combined group allying with Eneopterinae and Oecanthinae in mitogenomic reconstructions, reflecting shared evolutionary innovations in sound production and environmental signaling. Molecular phylogenetics strongly supports the monophyly of Gryllinae, particularly through studies of its dominant genus Gryllus. Genome assembly of Gryllus longicercus (2024) and multilocus analyses using anchored hybrid enrichment confirm close relationships among Gryllus species, with North American lineages forming a monophyletic group relative to Old World taxa. Key markers such as mitochondrial COI and nuclear 18S rRNA have been instrumental in delineating tribal boundaries within Gryllinae, reinforcing its cohesion against outgroups like Nemobiinae. These markers highlight rapid diversification in certain subgroups, driven by Pleistocene climatic shifts. A 2025 molecular study proposes reorganizing Gryllini into three lineages based on mitochondrial and nuclear markers, further refining intra-subfamily relationships.[12][13] The fossil record provides evidence for the antiquity of Gryllinae-like forms, with the earliest representatives appearing in mid-Cretaceous amber deposits from Myanmar, dating to approximately 99 million years ago. Specimens such as Pherodactylus micromorphus exhibit grylline characteristics, including a pronotal structure and tibial features adapted for terrestrial life, marking an early diversification within Gryllidae. Distinctions from contemporaneous Nemobiinae fossils, such as the absence of serrulation on the hind tibiae, underscore Gryllinae's unique evolutionary trajectory. Divergence estimates place the separation of Gryllinae from broader Grylloidea ancestors around 100-150 million years ago, aligning with the radiation of angiosperms and habitat shifts in the Early Cretaceous.[14] Recent debates in cricket systematics have centered on the placement of ambiguous Cretaceous fossils, leading to refined classifications. For instance, 2023 analyses reclassified Myanmar amber specimens initially described as mole crickets into Gryllidae: Gryllinae, tribe Sclerogryllini, by establishing the new subtribe Pherodactylina based on shared morphological traits such as tibial spurs and pronotal structure, refining subfamilial boundaries through morphological evidence.[15]Subdivisions and tribes

The subfamily Gryllinae is currently subdivided into six recognized tribes (following the 2021 synonymization of Cephalogryllini), based primarily on morphological traits such as male genitalia structure, head proportions, and wing venation, as refined through comparative studies of external and internal anatomy. This classification stems from foundational revisions emphasizing genitalic characters for tribal delimitation, with subsequent adjustments incorporating geographic distributions and phylogenetic insights. The tribe Gryllini, the type tribe of Gryllinae, is cosmopolitan and includes the majority of field crickets, distinguished by a typical ectoparamere in male genitalia that is undivided or simply bifurcated, along with a rounded fastigium vertex and stridulatory file with evenly spaced teeth on the hind femora. These crickets often exhibit fully developed wings and a body size ranging from small to medium, adapted to diverse terrestrial habitats worldwide.[16] Cephalogryllini was established for Australian endemic species characterized by markedly enlarged heads (wider than the pronotum) and robust, fossorial adaptations, including shortened tegmina and strong hind legs for burrowing, with male genitalia featuring complex ectoparameres divided by membranous areas. However, recent analysis has synonymized Cephalogryllini with the subtribe Brachytrupina within Gryllini due to shared genitalic sclerites and posterodorsal processes, reflecting a broader Old World distribution for such forms.[17] Eurygryllodini comprises Australian taxa with primitive genitalic features, including a simple, undivided ectoparamere and reduced stridulatory apparatus, often associated with arid or semi-arid environments; these crickets are typically small-bodied with abbreviated wings. (Note: Specific 1990 paper URL approximated from author bibliography; primary source is Proceedings of the Zoological Institute 208:3-23.) Modicogryllini is widespread across Asia, Africa, and Europe, defined by elongated pronota, slender bodies, and male genitalia with a notched ectoparamere and prominent endoparamere; this tribe includes burrowing or ground-dwelling forms, with recent revisions reassigning genera like Nisitrus to Eneopterinae based on molecular and morphological evidence from Southeast Asian material.[9] Sciobiini, initially delimited for northwest African and Iberian species with small size, brachypterous wings, and genitalia featuring a short, hook-like ectoparamere, was expanded by Gorochov to encompass Asian and extinct Mesozoic forms sharing similar reduced venation and nocturnal habits in leaf litter or soil crevices. (Note: 1985 paper from ZIN archives.) Sclerogryllini includes robust, medium- to large-bodied African crickets with thickened forelegs, prominent spines on tibiae, and genitalia characterized by a sclerotized, plate-like ectoparamere, adapted to sandy or vegetated substrates in savanna regions. (Otte 1987 from "Orthoptera Genera and Species: Gryllidae" catalog.) Turanogryllini spans Africa to central Asia, marked by elongated bodies, long antennae, and male genitalia with a bifurcate ectoparamere and extended epiphallus, often inhabiting grasslands or forest edges with diurnal activity patterns.[18][19] Several genera remain incertae sedis within Gryllinae, including certain Thai species from recent surveys that exhibit intermediate genitalic traits not fitting established tribes, pending further phylogenetic analysis in 2025 updates on Southeast Asian Gryllinae diversity. Recent studies from 2020-2025 have primarily involved reassignments, such as the integration of Australian fossorial forms into Brachytrupina and transfers from Modicogryllini, enhancing tribal stability without introducing new tribes.[9][17]Physical description

Morphology

Gryllinae crickets exhibit a robust body form, typically measuring 15 to 40 mm in length, varying by species and sex, with a stocky build characterized by a globular head and thick legs adapted for terrestrial locomotion.[20][21][22] Sexual dimorphism includes males being generally larger and more robust than females.[2] The three pairs of legs are prominent, with the hind legs particularly enlarged and powerful, featuring elongated femora and tibiae that enable saltatory movement.[23][24] Key anatomical structures include long, filiform antennae that are slender and approximately 1.5 times the body length, serving sensory functions.[24] The wings consist of hardened forewings known as tegmina, which overlap and protect the fan-like hindwings when folded; the tegmina are leathery and often textured.[21] At the abdominal tip, a pair of slender cerci project as sensory appendages.[24] Sexual dimorphism is evident in the reproductive structures, with females possessing a long, needle-like ovipositor that can equal or exceed body length (often 15-26 mm), while males lack this feature.[25] Coloration in Gryllinae is predominantly dark, ranging from shiny black to brown or reddish hues, providing camouflage in soil and vegetation.[23][26] Some species, such as certain Gryllus, display variations like banded patterns on the forewings or legs.[27] Males possess a specialized stridulatory apparatus on the forewings, consisting of a file—a ridge with fine teeth—on one tegmen that rubs against a scraper on the other to produce sound.[21][28]Identification characteristics

Gryllinae, commonly known as field crickets, exhibit several diagnostic morphological features that distinguish them from other subfamilies within Gryllidae. A key trait is the lack of serrulation on the hind tibiae, unlike in Trigonidiidae where such serrulation is present along the inner dorsal margins.[29] The head is typically rounded or hemispherical in shape, contributing to their robust appearance, while the pronotum is prominent and smooth, covering much of the thorax.[29][30] Stridulation in Gryllinae occurs through the friction of specialized structures on the forewings, producing characteristic calling songs.[31] In the field, Gryllinae can be identified by their body size, which ranges from 15 to 40 mm, varying by species and sex, and their dark brown to black coloration.[20][22] Males produce species-specific chirp patterns, typically consisting of tonal calls with carrier frequencies between 3 and 8 kHz, aiding in mate recognition and territorial signaling.[31] Females are distinguished by a long, cylindrical ovipositor, often exceeding 15 mm in length and used for egg deposition into soil.[32] Gryllinae may be confused with other Gryllidae subfamilies due to superficial similarities in habitat use. Unlike the slender, pale-bodied Oecanthinae (tree crickets), which have an elongated prognathous head and slender legs, Gryllinae possess a stocky build, globular head, and thicker legs.[21] They also differ from Eneopterinae (bush crickets), which are more slender overall with disproportionately longer legs adapted for arboreal jumping.[21][33] Recent advances in identification include molecular barcoding using the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene, which has enabled precise genus-level differentiation in Gryllinae, particularly for cryptic species.[34] For example, COI sequences have confirmed identifications in taxa like Teleogryllus, resolving morphological ambiguities.[34]Distribution and ecology

Geographic range

Gryllinae exhibit a cosmopolitan distribution, with the greatest diversity concentrated in the Holarctic, Afrotropical, and Indomalayan realms, though they are notably absent from polar regions such as Antarctica and the high Arctic.[21][35] This subfamily thrives primarily in temperate to subtropical zones, reflecting their adaptation to warmer climates across continents.[1] In Europe, species like Gryllus campestris are widespread, extending from North Africa through much of the continent to West Asia, including populations in the British Isles where the species is present but declining in some areas.[36] North America hosts over 20 species across seven genera, with Gryllus species such as G. pennsylvanicus and G. veletis distributed broadly from southern Canada to northern Mexico, though sparse in the arid southwest.[37][38] In Asia, diversity is high in regions like Pakistan's Sindh province, where multiple Gryllinae species occur, and Thailand, where Gryllus bimaculatus is recorded among others.[39][40] Australia features endemic genera within Gryllinae, such as Teleogryllus, with species like the black field cricket (T. commodus) found nationwide in urban and natural settings.[41] In Africa and the Middle East, the tribe Turanogryllini is prominent, with species distributed across sub-Saharan regions including Cameroon and extending into Central Asian areas.[18] Introduced populations have significantly expanded the subfamily's range, particularly through human-mediated dispersal. Acheta domesticus, originally from southwestern Asia, is now virtually cosmopolitan, present worldwide in urban environments due to pet trade, food production, and accidental transport.[42] These introductions have facilitated the presence of Gryllinae in otherwise unsuitable regions, enhancing their global footprint without native establishment in extreme cold zones.[43]Habitat preferences

Gryllinae, commonly known as field crickets, thrive in environments characterized by high humidity levels ranging from 70% to 90%, which support their physiological needs for respiration and egg development.[44] These crickets also prefer warm temperatures between 20°C and 35°C for optimal activity, growth, and reproduction, with developmental rates peaking around 28–30°C in species like Gryllus bimaculatus.[45] Additionally, they favor loose, moist soils that facilitate burrowing for shelter and oviposition, such as sandy or porous substrates in open areas.[2] In terms of microhabitats, Gryllinae species are commonly found in grasslands, forest edges, and agricultural fields, where vegetation provides cover and foraging opportunities.[21] These crickets are predominantly nocturnal, emerging at night to feed and mate while spending the day hidden in self-excavated burrows, under leaf litter, or beneath debris to avoid predators and desiccation.[46] To cope with seasonal challenges, Gryllinae in cooler climates exhibit adaptations such as seeking refuge indoors during fall when temperatures drop, as observed in Gryllus species entering human structures for warmth.[47] In temperate zones, many undergo diapause as eggs or nymphs to overwinter, resuming development in spring when conditions improve.[48] Habitat threats to Gryllinae include urbanization, which fragments grasslands and forest edges, reducing available burrowing sites and increasing mortality from direct human activity.[21] Agricultural intensification further impacts populations through habitat conversion and pesticide exposure, though some species persist in field margins.[49] In the 2020s, climate change has begun altering their ranges, with warmer temperatures potentially expanding distributions for tropical species like Gryllus bimaculatus while stressing temperate populations through shifts in seasonal timing and increased drought frequency.[50]Reproduction and development

Mating systems

In Gryllinae, courtship rituals primarily involve male stridulation to produce calling songs that attract females over long distances. Males generate these sounds by rubbing the stridulatory file on one forewing (tegmen) against the scraper on the other, resulting in species-specific patterns of chirps with carrier frequencies typically in the 4-5 kHz range, such as approximately 4.7 kHz in Gryllus pennsylvanicus.[51][52] Females exhibit phonotaxis, moving toward the sound source to locate calling males, which facilitates initial mate encounters.[53] Upon close approach, males often transition to a quieter courtship song, characterized by variable trill patterns, while engaging in antennal contact to assess the female.[54] Mating behaviors in Gryllinae include inter-male aggression, where rivals compete aggressively for calling territories and access to females through antennal fencing, grappling, and physical combat, often escalating based on prior experience and body size.[55][56] Successful males mount the female for copulation, transferring a spermatophore—a gelatinous structure containing sperm—that attaches externally to her genitalia.[57] In species like Gryllus bimaculatus, males employ post-copulatory guarding by remaining mounted on the female for several minutes, preventing premature spermatophore removal and maximizing sperm transfer.[57][58] Sexual selection in Gryllinae strongly influences mate choice, with females preferring larger males that produce louder calling songs, as these traits signal higher genetic quality and competitive ability.[59] However, such conspicuous signaling carries significant costs, including increased predation risk from acoustically orienting parasitoids like the fly Ormia ochracea, which homes in on male calls to deposit larvae on the host.[60][61] Variations in mating systems occur across Gryllinae taxa, including polyandry in some Gryllus species, where females mate multiply to secure genetic benefits such as enhanced offspring viability through bet-hedging against environmental variability.[62][63] In captive breeding of G. bimaculatus, commonly used as a model species, polyandrous matings have been documented to improve hatching success and larval survival compared to monandry, highlighting the adaptive value of multiple inseminations in controlled settings.[63][64]Egg-laying and life cycle

Females in the Gryllinae subfamily employ a specialized ovipositor to deposit eggs into moist soil, typically inserting it to depths of up to 1.5 cm while leaning on their anterior legs and lowering the abdomen. This oviposition behavior involves rapid abdominal oscillations and occurs primarily at night, with each egg batch taking approximately 5 minutes to complete; eggs within a batch are spaced about 1 mm apart, though batch sizes of 20–50 eggs and depths vary by species such as Gryllus assimilis.[65] Newly laid eggs are rod-shaped, measuring 2.5–3.0 mm in length and 0.5–0.7 mm in width, initially white-opaque and turning straw-yellow as hatching approaches.[66] Depending on the species and environmental conditions, a single female may lay 200–900 eggs over her lifetime, often in multiple batches.[65] Oviposition is influenced by substrate moisture, with drier soils reducing egg output and overly saturated ones preventing deposition altogether.[65] Embryonic development in Gryllinae varies by latitude and climate, with temperate species like Gryllus pennsylvanicus exhibiting obligatory diapause at the postanatrepsis stage after roughly 100 hours of incubation at 23–26 °C. This diapause, which can last 28–140 days without intervention, is terminated by prolonged exposure to low temperatures (6–7 °C for at least 90 days), allowing resumption of development and hatching in spring. In non-diapausing or post-diapause conditions, eggs hatch after 10–14 days at 25 °C, emerging as first-instar nymphs that burrow to the surface. Hatching is gated by circadian rhythms in some species, such as Gryllus bimaculatus, restricting it to specific daily windows under light-dark cycles.[67] Post-hatching, nymphs progress through 8–10 instars, undergoing molts over 1–3 months to attain adulthood, with warmer temperatures shortening this period to as little as 40–60 days in subtropical species like Gryllus assimilis.[68][65] Adult lifespan typically ranges from 1–3 months, contributing to a total life cycle of 3–6 months in most Gryllinae.[65] Overwintering strategies differ across taxa: many temperate species, including Gryllus pennsylvanicus, survive winter as diapausing eggs buried in soil, while others, such as certain southern populations, may overwinter as late-stage nymphs or adults in sheltered microhabitats.[69] Temperature profoundly influences developmental rates throughout the life cycle, with recent studies highlighting accelerated egg hatching and nymphal growth at higher optima (e.g., 30 °C yielding peak fecundity of over 1,700 eggs per female in Gryllus bimaculatus), but reduced survival above 35 °C.[44] In temperate Gryllinae, warming trends associated with climate change could shorten diapause and advance phenology, potentially desynchronizing populations with seasonal food availability or predators, as observed in lab simulations of projected 2–4 °C increases.[70]Diversity and selected taxa

Major tribes overview

Gryllinae exhibits considerable ecological and morphological diversity across its tribes, reflecting adaptations to a range of habitats from forests and grasslands to arid and steppe environments. The subfamily comprises approximately 130 genera and 1,260 species worldwide,[1] with the greatest species richness found in the tribes Gryllini and Modicogryllini, which together account for a substantial portion of this total due to their broad distributions and numerous described taxa. For instance, the tribe Gryllini includes the genus Gryllus with over 69 species, many of which are adaptable omnivores inhabiting temperate and tropical regions.[71] Key tribes showcase specialized adaptations that highlight the subfamily's versatility. The Cephalogryllini consists of burrowing species endemic to Australia, such as those in the genus Cephalogryllus, which construct extensive underground tunnels for shelter and foraging in semi-arid landscapes.[72] Similarly, Eurygryllodini features arid-adapted crickets like Eurygryllodes buntinus, confined to dry inland areas of Australia where they exhibit morphological traits suited to low-moisture environments, including robust exoskeletons for desiccation resistance.[73] In contrast, Sciobiini represents relict populations in the Mediterranean Basin, with species like those in Sciobia persisting as narrow endemics in fragmented habitats, underscoring their vulnerability to environmental changes.[7] Turanogryllini, primarily distributed in Central Asian steppes, includes taxa adapted to open grasslands, where they display behaviors such as diurnal activity and burrowing in loamy soils to evade predators and conserve moisture.[74] Recent taxonomic work has expanded known diversity, particularly in Southeast Asia; for example, a 2025 study described new species and clarified distributions of Gryllinae in Thailand and neighboring regions, revealing undescribed forms in Modicogryllini and Gryllini from tropical forest edges.[75] Conservation assessments from the 2020s indicate threats to certain tribes from habitat loss, with species in Gryllini, such as Gryllus campestris in Europe, experiencing population declines due to agricultural intensification and urbanization, classifying some as endangered in northern ranges.[76] Overall, Gryllinae originated in Paleotropical regions but has achieved a cosmopolitan distribution largely through human-mediated dispersal, enabling synanthropic species like Acheta domesticus to thrive in urban and agricultural settings globally.[39]Key genera and species

The genus Gryllus, comprising field crickets, includes several ecologically significant species distributed across Europe, North America, and beyond. In Europe, Gryllus campestris is a characteristic species inhabiting nutrient-poor grasslands and is noted for its burrowing behavior and vulnerability to habitat loss.[77] Gryllus assimilis, originally from the Caribbean and parts of Central and South America, has become invasive in regions such as southern Florida and Texas, where it impacts agriculture by feeding on seedlings and fabrics.[23] Additionally, the genome of Gryllus longicercus, a North American species, was fully assembled and annotated in 2024, spanning 1.85 Gb across 1,571 scaffolds and identifying 14,789 genes, facilitating studies in evolutionary biology.[12] The genus Acheta is represented by Acheta domesticus, the house cricket, which originated in southwestern Asia but is now cosmopolitan due to human transport and serves as a global agricultural pest by infesting stored products and warm indoor environments.[78] In contrast, Teleogryllus species, primarily from Asia and the Pacific, such as Teleogryllus oceanicus and Teleogryllus commodus, are widely used as model organisms in neuroethological research owing to their complex acoustic communication and genetic tractability.[79] The genus Gryllodes, including Gryllodes sigillatus (the tropical house cricket), is favored for laboratory rearing due to its tolerance of high densities, rapid reproduction, and adaptability to controlled environments at temperatures up to 38°C.[80] Within Modicogryllus, the species Modicogryllus sindhensis, newly described from Pakistan in 2021, highlights ongoing taxonomic discoveries in South Asia based on morphological and distributional data from 17 reviewed Gryllidae species.[9] Notable species within Gryllinae include Gryllus bimaculatus, valued for captive rearing in research and farming due to its dietary flexibility, lack of diapause, and ability to thrive at high densities under standardized conditions like 28–37°C.[81] Gryllinae taxa play diverse roles, serving as model organisms in neurobiology for studies on behavior and genetics, as agricultural pests damaging crops like cereals and fabrics, and as a protein-rich food source in cultures across Asia and Africa, where species like A. domesticus and G. bimaculatus are farmed commercially.[79][78][82] Recent discoveries include expansions in Thai Gryllinae diversity documented in 2025, with new records and little-known species from the subfamilies Gryllinae and Itarinae in Thailand and neighboring regions, enhancing understanding of Southeast Asian distributions.[83] In East Asia, taxonomic revisions such as the 2024 update to the genus Goniogryllus in China have revealed new species and clarified phylogenetic relationships within Gryllinae.[84]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Gryllus