Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

HaloTag

View on Wikipedia

HaloTag is a self-labeling protein tag. It is a 297 residue protein (33 kDa) derived from a bacterial enzyme, designed to covalently bind to a synthetic ligand. The bacterial enzyme can be fused to various proteins of interest.[1] The synthetic ligand is chosen from a number of available ligands in accordance with the type of experiments to be performed. This bacterial enzyme is a haloalkane dehalogenase, which acts as a hydrolase and is designed to facilitate visualization of the subcellular localization of a protein of interest, immobilization of a protein of interest, or capture of the binding partners of a protein of interest within its biochemical environment.[2] The HaloTag is composed of two covalently bound segments including a haloalkane dehalogenase and a synthetic ligand of choice. These synthetic ligands consist of a reactive chloroalkane linker bound to a functional group.[3] Functional groups can either be biotin (can be used as an affinity tag) or can be chosen from five available fluorescent dyes including Coumarin, Oregon Green, Alexa Fluor 488, diAcFAM, and TMR. These fluorescent dyes can be used in the visualization of either living or chemically fixed cells.[4]

Mechanism

[edit]

The HaloTag is a hydrolase, which has a genetically modified active site, which specifically binds the reactive chloroalkane linker and has an increased rate of ligand binding.[5] The reaction that forms the bond between the protein tag and chloroalkane linker is fast and essentially irreversible under physiological conditions due to the terminal chlorine of the linker portion.[6] In the aforementioned reaction, nucleophilic attack of the chloroalkane reactive linker causes displacement of the halogen with an amino acid residue, which results in the formation of a covalent alkyl-enzyme intermediate. This intermediate would then be hydrolyzed by an amino acid residue within the wild-type hydrolase.[7] This would lead to regeneration of the enzyme following the reaction. However, in the modified haloalkane dehalogenase (HaloTag), the reaction intermediate cannot proceed through a subsequent reaction because it cannot be hydrolyzed due to the mutation in the enzyme. This causes the intermediate to persist as a stable covalent adduct with which there is no associated back reaction.[8]

Uses

[edit]

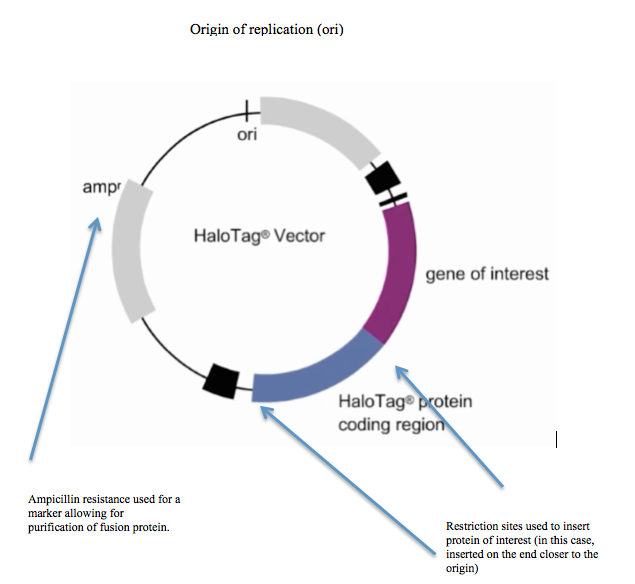

HaloTagged fusion proteins can be expressed using standard recombinant protein expression techniques.[9] Furthermore, there are several commercial vectors available that just require insertion of a gene of interest.[10] Since bacterial dehalogenases are relatively small and the reactions described above are foreign to mammalian cells, there is no interference by endogenous mammalian metabolic reactions.[11] Once the fusion protein has been expressed, there is a wide range of potential areas of experimentation including enzymatic assays, cellular imaging, protein arrays, determination of sub-cellular localization, and many additional possibilities.[12]

Recently, HaloTag has been engineered to create hybrid protein + small molecule biosensors of neuronal activity.[13] These sensors undergo a conformational change in response to calcium concentration spikes during neuronal firing; this conformational change modulates the conformation of a HaloTag-bound dye molecule.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Los GV, Encell LP, McDougall MG, Hartzell DD, Karassina N, Zimprich C, et al. (June 2008). "HaloTag: a novel protein labeling technology for cell imaging and protein analysis". ACS Chemical Biology. 3 (6): 373–82. doi:10.1021/cb800025k. PMID 18533659.

- ^ Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY (April 2006). "The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function". Science. 312 (5771): 217–24. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..217G. doi:10.1126/science.1124618. PMID 16614209. S2CID 1288600.

- ^ Kogure T, Karasawa S, Araki T, Saito K, Kinjo M, Miyawaki A (May 2006). "A fluorescent variant of a protein from the stony coral Montipora facilitates dual-color single-laser fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy". Nature Biotechnology. 24 (5): 577–81. doi:10.1038/nbt1207. PMID 16648840. S2CID 19616823.

- ^ Miller LW, Cornish VW (February 2005). "Selective chemical labeling of proteins in living cells". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 9 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.12.007. PMID 15701454.

- ^ Pries F, Kingma J, Krooshof GH, Jeronimus-Stratingh CM, Bruins AP, Janssen DB (May 1995). "Histidine 289 is essential for hydrolysis of the alkyl-enzyme intermediate of haloalkane dehalogenase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (18): 10405–11. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.18.10405. PMID 7737973.

- ^ Waugh DS (June 2005). "Making the most of affinity tags". Trends in Biotechnology. 23 (6): 316–20. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.03.012. PMID 15922084.

- ^ Chen I, Ting AY (February 2005). "Site-specific labeling of proteins with small molecules in live cells". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 16 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2004.12.003. PMID 15722013.

- ^ Marks KM, Nolan GP (August 2006). "Chemical labeling strategies for cell biology". Nature Methods. 3 (8): 591–6. doi:10.1038/nmeth906. PMID 16862131. S2CID 27848267.

- ^ Adams SR, Campbell RE, Gross LA, Martin BR, Walkup GK, Yao Y, et al. (May 2002). "New biarsenical ligands and tetracysteine motifs for protein labeling in vitro and in vivo: synthesis and biological applications". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (21): 6063–76. Bibcode:2002JAChS.124.6063A. doi:10.1021/ja017687n. PMID 12022841.

- ^ "HaloTag vectors at Promega". Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ Naested H, Fennema M, Hao L, Andersen M, Janssen DB, Mundy J (June 1999). "A bacterial haloalkane dehalogenase gene as a negative selectable marker in Arabidopsis" (PDF). The Plant Journal. 18 (5): 571–6. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00477.x. hdl:11370/3359ce65-5249-4057-bd7d-b22451ea5e85. PMID 10417708.

- ^ Janssen DB (April 2004). "Evolving haloalkane dehalogenases". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 8 (2): 150–9. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.02.012. PMID 15062775.

- ^ a b Deo, Claire; Abdelfattah, Ahmed S.; Bhargava, Hersh K.; Berro, Adam J.; Falco, Natalie; Farrants, Helen; Moeyaert, Benjamien; Chupanova, Mariam; Lavis, Luke D.; Schreiter, Eric R. (June 2021). "The HaloTag as a general scaffold for far-red tunable chemigenetic indicators". Nature Chemical Biology. 17 (6): 718–723. doi:10.1038/s41589-021-00775-w. ISSN 1552-4469. PMID 33795886. S2CID 232763093.