Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

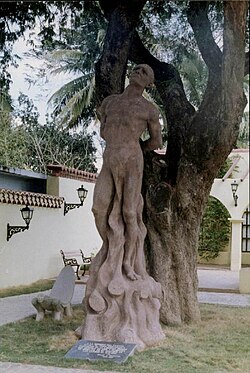

Hatuey

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Hatuey (/ɑːˈtweɪ/), also Hatüey (/ˌɑːtuˈeɪ/; died February 2, 1512), was a Taíno Cacique (chief) of the Hispaniolan cacicazgo of Guanaba (in present-day La Gonave, Haiti).[1] He lived from the late 15th until the early 16th century. Chief Hatuey and many of his tribesmen travelled from present-day La Gonave by canoe to Cuba to warn the Taíno in Cuba about the Spaniards that were arriving to conquer the island.

He later attained legendary status for leading a group of natives in a fight against the invasion of the Spaniards, thus becoming one of the first fighters against Spanish colonialism in the New World. He is celebrated as "Cuba's first national hero".[3]

Life and death

[edit]In 1511, Diego Velázquez set out from Hispaniola to conquer what is now known as present-day La Gonave, Haiti and Dominican Republic to subjugate the indigenous people, the Taíno, who had previously been recorded by Christopher Columbus. Velázquez was preceded, however, by Hatuey, who fled Hispaniola with a party of four hundred in canoes and warned some of the Native people of eastern Cuba about what to expect from the Spaniards.[4]

Bartolomé de Las Casas later attributed the following speech to Hatuey which was addressed against Christianity. He showed the Taíno of Caobana a basket of gold and jewels, saying:

They have a God whom they worship and adore, and it is in order to get that God from us so that they can worship Him that they conquer us and kill us ... Here is the God of the Christians. If you agree, we will do areitos (which is their word for certain kinds of traditional dance) in honour of this God and it may be that we shall please Him and He will order the Christians to leave us unharmed.[5]

The Taíno chiefs in Cuba did not respond to Hatuey's message, and few joined him to fight. Hatuey resorted to guerrilla tactics against the Spaniards, and was able to confine them for a time. He and his fighters were able to kill at least eight Spanish soldiers. Eventually, using mastiffs and torturing the native people for information, the Spaniards succeeded in capturing him. On 2 February 1512, he was tied to a stake and burned alive at Yara, near the present-day city of Bayamo.[6]

Before he was burned, a priest asked Hatuey if he would accept Jesus and go to heaven. Las Casas recalled the reaction of the chief:

[Hatuey], thinking a little, asked the religious man if Spaniards went to heaven. The religious man answered yes... The chief then said without further thought that he did not want to go there but to hell so as not to be where they were and where he would not see such cruel people. This is the name and honour that God and our faith have earned.[7][8]

Legacy

[edit]Hatuey is considered "Cuba's first national hero" and one of the earliest fighters against Spanish colonialism.[3] The town of Hatuey, located south of Sibanicú in the Camagüey Province of Cuba, was named after him.

Hatuey also lives on as a beer brand name. Beer has been brewed in Santiago de Cuba and sold under the Hatuey brand name since 1927, initially by the native Cuban company, Compañia Ron Bacardi S.A. After nationalization of industry in 1960, brewing was taken over by Empresa Cerveceria Hatuey Santiago. Beginning in 2011, the Bacardi family again began making beers in the United States to market under the Hatuey label.[9][10] Hatuey is also a brand of a type of sugary, non-alcoholic malt beverage called malta.[11][full citation needed][12] Hatuey is also a Dominican brand of soda cracker.[13][full citation needed]

The logo of the Cuban cigar and cigarette brand Cohiba is a picture of Hatuey.

In a 2010 film shot in Bolivia, Even the Rain, Hatuey is a main character in the film-within-the-film. The film includes a cinematic account of Hatuey's execution.[14]

Fine arts

[edit]The imagery of Hatuey has been appropriated and/or incorporated into diverse artistic genres, most notably into the Afro-Cuban Yiddish opera, Hatuey: Memory of Fire.[15][16][17] In the visual arts, multiple artists have used the Taíno chief's image, most notably Cuban-American artist Ric Garcia[18] and U.S. Marine Corps artist Donald Dickson,[19] among others.

See also

[edit]- List of Taínos

- Taíno people

- Radbod of Frisia, who claimed a similar preference to "be in hell [rather] than to go to heaven"

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Taínos: Past & Present". Powhatan Museum. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023.

- ^ Spanish: "A la memoria del cacique Hatuey, el indio inolvidable, precursor de la libertad cubana que ofrendo su vida y glorifico su rebeldía en el martirio de las llamas el 2-2-1512. Deleg. Monumentos Yara 1999"

- ^ a b Running Fox (January 1998). "The Story of Cacique Hatuey, Cuba's First National Hero". La Voz del Pueblo Taíno [The Voice of the Taíno People]. United Confederation of Taíno People, U.S. Regional Chapter.

- ^ J. A. Sierra (August 2006). "The Legend of Hatuey". The History of Cuba. Retrieved September 9, 2006.

- ^ Bartolomé de Las Casas (1992). A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Translated by Nigel Griffin. London: Penguin. pp. 27–28.

- ^ Barreiro, Jose (1990). "A Note on Taino". In Akwe, Cornell. View From the Shore. Pon Press.[page needed]

- ^ Luis N. Rivera, Luis Rivera Pagán (1992). A violent evangelism: the political and religious conquest of the Americas. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 260. ISBN 0-664-25367-9.

- ^ "Brevísima relación de la destruición de las Indias". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Spanish: "Él, pensando un poco, preguntó al religioso si iban cristianos al cielo. El religioso le respondió que sí, pero que iban los que eran buenos. Dijo luego el cacique, sin más pensar, que no quería él ir allá, sino al infierno, por no estar donde estuviesen y por no ver tan cruel gente. Ésta es la fama y honra que Dios y nuestra fe ha ganado con los cristianos que han ido a las Indias."

- ^ Klein, Lee (December 6, 2011). "Hatuey Beer Returns as a Microbrew". Miami New Times..

- ^ "Bacardi Launches National Distribution of Hatuey". Brewbound. November 21, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Soda Pop Stop". Archived 2011-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Quaffmaster. "Malta Hatuey". Weird Soda Review. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Hatuey".

- ^ Holden, Stephen (February 17, 2011). "Discovering Columbus's Exploitation". The New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Bronxnet. "OPEN Artist Spotlight with cast of Hatuey: Memory of Fire". Bronxnet. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Afro-Cuban Yiddish opera with music by The Klezmatics' Frank London". Arts & Cultural Programming. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Hatuey Memory Of Fire". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Hatuey: Rebel Chief – Maryland Milestones". Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Conner, Owen L. (August 6, 2020). "The Drinks of the Marine Corps: Hatuey Beer". National Museum of the Marine Corps. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

External links

[edit]Hatuey

View on GrokipediaHatuey (d. 1512) was a Taíno cacique who organized armed resistance against the initial Spanish conquest of Cuba.[1]

Originating from the island of Hispaniola, where he had observed the brutality of early Spanish colonization under figures like Nicolás de Ovando, Hatuey escaped by canoe in late 1511 with approximately 400 followers to Cuba, alerting local Taíno communities to the invaders' primary motivation of extracting gold and urging unified opposition.[2][3]

There, he forged alliances among caciques and directed guerrilla ambushes against the 300-man expedition led by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, which had landed to establish settlements and enforce tribute.[1][2]

Despite initial successes, Spanish forces, employing war dogs trained to track and maul natives, captured Hatuey following betrayal by a follower; on February 2, 1512, near present-day Yara, he was tied to a stake and burned alive as a public deterrent.[3][1]

Eyewitness Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar accompanying the expedition, recorded Hatuey's final rejection of baptism, stating that if Spaniards inhabited heaven, he preferred hell to avoid their company—a testament to the chief's unyielding contempt for the colonizers' hypocrisy and violence.[3][1]