Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

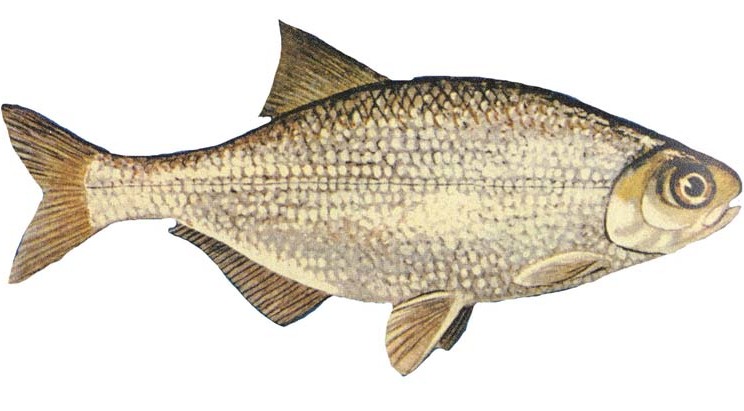

Mooneye

View on Wikipedia

| Mooneye | |

|---|---|

| |

| Hiodon tergisus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Hiodontiformes |

| Family: | Hiodontidae Cuvier & Valenciennes, 1846 |

| Genus: | Hiodon Lesueur, 1818 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Hiodontidae, commonly called mooneyes, is a family of ray-finned fish with a single included genus Hiodon. The genus comprise two extant species native to North America and three to five extinct[1] species recorded from Paleocene to Eocene age fossils. They are large-eyed, fork-tailed fish that superficially resemble shads. The vernacular name comes from the metallic shine of their eyes.

The higher classification of the mooneyes is not yet fully established. Some sources have place them in their own order, Hiodontiformes, while others retain them in the order Osteoglossiformes.

Species

[edit]- Hiodon alosoides (Rafinesque, 1819)

The goldeye, Hiodon alosoides, is widespread across eastern North America, and is notable for a conspicuous golden iris in the eyes. It prefers turbid slower-moving waters of lakes and rivers, where it feeds on a wide variety of organisms including insects, crustaceans, small fish, and mollusks. The fish has been reported up to 52 centimetres (20 in) in length.

- †Hiodon consteniorum Li & Wilson, 1994

- †Hiodon falcatus (Grande, 1979)

- †Hiodon rosei (Hussakof, 1916)

- Hiodon tergisus Lesueur, 1818

The mooneye, Hiodon tergisus, is also widespread across eastern North America, living in the clear waters of lakes, ponds, and rivers. It consumes aquatic invertebrates, insects, and fish. Mooneyes can reach 47 centimetres (19 in) in length.

- †Hiodon woodruffi Wilson, 1978

An Early Eocene, Ypresian to Late Eocene, Lutetian species. Hiodon woodruffi was described from fossils found in the Klondike Mountain Formation, Washington and Horsefly shale, British Columbia. Further finds have increased the known paleogeographic range to include the Kishenehn Formation of northwestern Montana.

- ?†Hiodon shuyangensis Shen, 1989

References

[edit]- ^ Hilton, E. J.; Grande, L. (2008). "Fossil Mooneyes (Teleostei: Hiodontiformes, Hiodontidae) from the Eocene of western North America, with a reassessment of their taxonomy". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 295 (1): 221–251. Bibcode:2008GSLSP.295..221H. doi:10.1144/sp295.13.

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2020) |

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Hiodontidae". FishBase. June 2011 version.