Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Monotypic taxon

View on Wikipedia

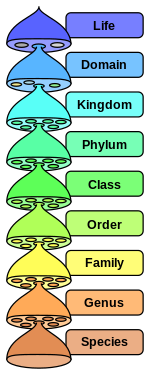

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon.[1] A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa.[contradictory] In the case of genera, the term "unispecific" or "monospecific" is sometimes preferred. In botanical nomenclature, a monotypic genus is a genus in the special case in which a genus and a single species are simultaneously described.[2]

Theoretical implications

[edit]

Monotypic taxa present several important theoretical challenges in biological classification. One key issue is known as "Gregg's Paradox": if a single species is the only member of multiple hierarchical levels (for example, being the only species in its genus, which is the only genus in its family), then each level needs a distinct definition to maintain logical structure. Otherwise, the different taxonomic ranks become effectively identical, which creates problems for organizing biological diversity in a hierarchical system.[3]

When taxonomists identify a monotypic taxon, this often reflects uncertainty about its relationships rather than true evolutionary isolation. This uncertainty is evident in many cases across different species. For instance, the diatom Licmophora juergensii is placed in a monotypic genus because scientists have not yet found clear evidence of its relationships to other species.[3]

Some taxonomists argue against monotypic taxa because they reduce the information content of biological classifications. As taxonomists Backlund and Bremer explain in their critique, "'Monotypic' taxa do not provide any information about the relationships of the immediately subordinate taxon".[4] When a monotypic taxon is sister to a single larger group, it might be merged into that group; however, when it is sister to multiple other groups, it may need to remain separate to maintain a natural classification.[4]

From a cladistic perspective, which focuses on shared derived characteristics to determine evolutionary relationships, the theoretical status of monotypic taxa is complex. Some argue that they can only be justified when relationships cannot be resolved through synapomorphies (shared derived characteristics); otherwise, they would necessarily exclude related species and thus be paraphyletic.[5] However, others contend that while most taxonomic groups can be classified as either monophyletic (containing all descendants of a common ancestor) or paraphyletic (excluding some descendants), these concepts do not apply to monotypic taxa because they contain only a single member.[6]

Monotypic taxa are part of a broader challenge in biological classification known as aphyly – situations in which evolutionary relationships are poorly supported by evidence. This includes both monotypic groups and cases where traditional groupings are found to be artificial. Understanding how monotypic taxa fit into this bigger picture helps identify areas needing further research.[3]

The German lichenologist Robert Lücking suggests that the common application of the term monotypic is frequently misleading "since each taxon by definition contains exactly one type and is hence 'monotypic', regardless of the total number of units", and suggests using "monospecific" for a genus with a single species, and "monotaxonomic" for a taxon containing only one unit.[7]

Conservation implications

[edit]Species in monotypic genera tend to be more threatened with extinction than average species. Studies have found this pattern to be particularly pronounced in amphibians, of which about 6.56% of monotypic genera are critically endangered, compared to birds and mammals, of which around 4.54% and 4.02%, respectively, of monotypic genera face critical endangerment.[8]

Studies have found that extinction of monotypic genera is particularly associated with island species. Among 25 documented extinctions of monotypic genera studied, 22 occurred on islands, with flightless birds being particularly vulnerable to human impact.[8]

Examples

[edit]Just as the term monotypic is used to describe a taxon including only one subdivision, the contained taxon can also be referred to as monotypic within the higher-level taxon, e.g., a genus monotypic within a family. Some examples of monotypic groups are:

Plants

[edit]- The division Ginkgophyta is monotypic, containing the single class Ginkgoopsida. This class is also monotypic, containing the single order Ginkgoales, which has only the single family Ginkgoaceae, containing a single genus Ginkgo with a single species Ginkgo biloba.[9]

- In the order Amborellales, there is only one family, Amborellaceae, there is only one genus, Amborella, and in this genus there is only one species, Amborella trichopoda.

- The conifer Sciadopitys verticillata is the only species in the monotypic genus Sciadopitys, and also the only member of the family Sciadopityaceae.[10] Multiple other conifer genera are monotypic, but are members of larger families; examples include Cathaya, Diselma, Fitzroya, Glyptostrobus, Metasequoia, Microcachrys, Nothotsuga, Parasitaxus, Saxegothaea, Sequoia, Sequoiadendron, Sundacarpus, Tetraclinis, Thujopsis and Wollemia.

- The flowering plant Breonadia salicina is the only species in the monotypic genus Breonadia.

- The family Cephalotaceae includes only one genus, Cephalotus, and only one species, Cephalotus follicularis – the Albany pitcher plant.

Animals

[edit]- The platypus is the only member of the monotypic genus Ornithorhynchus.

- The aardvark is the only extant member of the genus Orycteropus, the family Orycteropodidae, and the order Tubulidentata.[11]

- The madrone butterfly is the only species in the monotypic genus Eucheira. However, there are two subspecies of this butterfly, E. socialis socialis and E. socialis westwoodi, which means the species E. socialis is not monotypic.[12]

- Delphinapterus leucas, the beluga whale, is the only member of its genus and lacks subspecies.[13]

- Dugong dugon is the only species in the monotypic genus Dugong.[14]

- Homo sapiens (humans) are monotypic, as they have too little genetic diversity to have any accepted living subspecies.[15]

- The narwhal, a medium-sized cetacean, is the only member of the monotypic genus Monodon.[16]

- The palmchat is the only member of the genus Dulus and the only member of the family Dulidae.[17]

- The salamanderfish (Lepidogalaxias salamandroides) is the only member of the order Lepidogalaxiiformes, which is the sister group to the remaining euteleosts.[18]

- Ozichthys albimaculosus, the cream-spotted cardinalfish, which is found in tropical Australia and southern New Guinea, is the type species of the monotypic genus Ozichthys.[19]

- The bearded reedling is the only species in the monotypic genus Panurus, which is the only genus in the monotypic family Panuridae; it does however have three subspecies so it is not strictly monotypic.[20]

-

In the order Amborellales, there is only one family, Amborellaceae, and there is only one genus, Amborella, and in this genus there is only one species, Amborella trichopoda.

-

The family Cephalotaceae has only one genus, Cephalotus, which contains only one species, Cephalotus follicularis, the Australian pitcher plant.

Other

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mayr E, Ashlock PD. (1991). Principles of Systematic Zoology (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-041144-1

- ^ McNeill, J.; Barrie, F.R.; Buck, W.R.; Demoulin, V.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.L.; Herendeen, P.S.; Knapp, S.; Marhold, K.; Prado, J.; Reine, W.F.P.h.V.; Smith, G.F.; Wiersema, J.H.; Turland, N.J. (2012). "Article 38". International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code) adopted by the Eighteenth International Botanical Congress Melbourne, Australia, July 2011. Vol. Regnum Vegetabile 154. A.R.G. Gantner Verlag KG. ISBN 978-3-87429-425-6.

- ^ a b c Ebach, Malte C.; Williams, David M. (2010). "Aphyly: A Systematic Designation for a Taxonomic Problem". Evolutionary Biology. 37 (2–3): 123–127. Bibcode:2010EvBio..37..123E. doi:10.1007/s11692-010-9084-5.

- ^ a b Backlund, Anders; Bremer, Kåre (1998). "To Be or Not to Be. Principles of Classification and Monotypic Plant Families". Taxon. 47 (2): 391–400. Bibcode:1998Taxon..47..391B. doi:10.2307/1223768. JSTOR 1223768.

- ^ Platnick, Norman I. (1976). "Are Monotypic Genera Possible?". Systematic Zoology. 25 (2): 198–199. doi:10.2307/2412749. JSTOR 2412749.

- ^ Potter, Daniel; Freudenstein, John V. (2005). "Character-based phylogenetic Linnaean classification: taxa should be both ranked and monophyletic". Taxon. 54 (4): 1033–1035. Bibcode:2005Taxon..54.1033P. doi:10.2307/25065487. JSTOR 25065487.

- ^ Lücking, Robert (2019). "Stop the abuse of time! Strict temporal banding is not the future of rank-based classifications in Fungi (including lichens) and other organisms". Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 38 (3): 199–253 [216]. Bibcode:2019CRvPS..38..199L. doi:10.1080/07352689.2019.1650517.

- ^ a b Vargas, Pablo (2023). "Exploring 'endangered living fossils' (ELFs) among monotypic genera of plants and animals of the world". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 11 e1100503. Bibcode:2023FrEEv..1100503V. doi:10.3389/fevo.2023.1100503. hdl:10261/353582.

- ^ Wu, Chung-Shien; Chaw, Shu-Miaw; Huang, Ya-Yi (2013). "Chloroplast Phylogenomics Indicates that Ginkgo biloba Is Sister to Cycads". Genome Biology and Evolution. 5 (1): 243–254. doi:10.1093/gbe/evt001. PMC 3595029. PMID 23315384.

- ^ "Sciadopityaceae". Plants of the World Online. 2020-11-19. Retrieved 2025-06-04.

- ^ Schlitter, D. A. (2005). "Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.)". Johns Hopkins University Press: 86. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Kevan, P. G.; Bye, R. A. (1991). "The natural history, sociobiology, and ethnobiology of Eucheira socialis Westwood (Lepidoptera: Pieridae), a unique and little-known butterfly from Mexico". Entomologist. 110: 146–165.

- ^ Designatable Units for Beluga Whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in Canada (PDF) (Report). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2016.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas A.; Webber, Marc A.; Pitman, Robert L. (2015). "Taxonomic Groupings Above the Species Level". Marine Mammals of the World. pp. 17–23. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-409542-7.50003-2. ISBN 978-0-12-409542-7.

- ^ Premo, L. S.; Hublin, J.-J. (6 January 2009). "Culture, population structure, and low genetic diversity in Pleistocene hominins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (1): 33–37. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106...33P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809194105. PMC 2629215. PMID 19104042.

- ^ COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the narwhal Monodon monoceros in Canada (PDF) (Report). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2004.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Dulus dominicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22708129A94150155. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22708129A94150155.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ A phylogenomic approach to reconstruct interrelationships of main clupeocephalan lineages with a critical discussion of morphological apomorphies

- ^ Fraser, Thomas H. (14 August 2014). "A new genus of cardinalfish from tropical Australia and southern New Guinea (Percomorpha: Apogonidae)". Zootaxa. 3852 (2): 283–293. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3852.2.7. PMID 25284398.

- ^ "Nicators, Bearded Reedling, larks – IOC World Bird List". IOC World Bird List – Version 14.2. 2025-02-20. Retrieved 2025-06-04.

- ^ Seenivasan R, Sausen N, Medlin LK, Melkonian M (2013). Waller RF (ed.). "Picomonas judraskeda gen. et sp. nov.: the first identified member of the Picozoa phylum nov., a widespread group of picoeukaryotes, formerly known as 'picobiliphytes'". PLOS ONE. 8 (3) e59565. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...859565S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059565. PMC 3608682. PMID 23555709.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of monotypic at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of monotypic at Wiktionary

Monotypic taxon

View on GrokipediaDefinition and History

Definition

A monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group within biological classification that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon of the next lower rank.[9] For instance, this occurs when a genus includes a single species or a family encompasses just one genus.[10] This concept applies strictly within hierarchical systems like the Linnaean classification, where ranks are nested sequentially from domain to species. The term "monotypic" is distinct from related descriptors such as "monospecific," which specifically refers to a genus containing only one species, or "unispecific," an alternative term sometimes used for the same situation in genera.[11] Monotypic should be avoided in non-hierarchical contexts, such as describing a species without subspecies, where "monotypic species" may instead imply no infraspecific divisions.[12] Monotypy can manifest at various levels of the Linnaean hierarchy, from species (lacking subspecies) to higher ranks like order or class. A classic example is the aardvark (Orycteropus afer), which is the sole extant species in its genus Orycteropus, family Orycteropodidae, and order Tubulidentata.[13] Similarly, the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) represents the only species in its genus Ornithorhynchus and family Ornithorhynchidae within the order Monotremata.[14] These cases illustrate how monotypy highlights unique evolutionary lineages with no close living relatives at multiple taxonomic levels.Historical Development

The term "monotypic" in taxonomy derives from the Greek roots monos (meaning "single" or "alone") and typos (meaning "type" or "model"), reflecting a taxonomic group containing only one subordinate unit, and it first appeared in scientific literature around 1875–1880.[15] Early informal uses emerged in 19th-century classifications, where naturalists described genera or higher taxa with a single species as distinct but anomalous entities within hierarchical systems, building on implied structures in Linnaeus's 18th-century binomial nomenclature without employing the term explicitly.[16] Key milestones in the formal recognition of monotypic taxa occurred in the 20th century, particularly with the 1964 edition of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), which standardized typification principles and indirectly supported the concept by emphasizing name-bearing types in subordinate taxa, allowing for monotypic arrangements without redundancy. The rise of cladistics in the 1970s and 1980s, pioneered by Willi Hennig, further shaped this development by prioritizing monophyletic groups based on shared derived characters, often challenging monotypic taxa as potentially artificial unless they demonstrated clear evolutionary isolation.[17] Influential works include Ernst Mayr's 1942 Systematics and the Origin of Species, which advanced the biological species concept—defining species as reproductively isolated populations—and indirectly influenced monotypy by clarifying delimitations that could result in single-species genera.[18] Similarly, John R. Gregg's 1954 The Language of Taxonomy introduced a logical paradox, arguing that monotypic taxa create set-theoretic inconsistencies in ranked hierarchies, as a higher rank with one subordinate offers no additional classificatory information beyond the subordinate itself.[19] More recently, in 2020, lichenologist Robert Lücking proposed replacing "monotypic" with "monotaxic" to avoid confusion, noting that all taxa are inherently monotypic via their type, and advocating for the term to denote taxa with only one immediate subordinate taxon.[20] The understanding of monotypic taxa evolved significantly from pre-Darwinian views, where they were regarded as anomalies or gaps in a fixed, divinely ordained hierarchy of immutable species, to post-1859 perspectives following Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, which reframed them as potential outcomes of evolutionary processes like geographic isolation and adaptive divergence, signaling unique lineages rather than imperfections in classification.[21] This shift integrated monotypic taxa into dynamic phylogenetic frameworks, emphasizing their role in reflecting evolutionary history over rigid categorical completeness.Taxonomy and Nomenclature

Taxonomic Ranks and Criteria

Monotypy manifests across a spectrum of taxonomic ranks, where a taxon contains only a single immediately subordinate taxon at that level. At the species rank, monotypy occurs when a species lacks recognized subspecies, often due to limited intraspecific variation or insufficient sampling. For genera, it is defined by the presence of just one species, a common occurrence in isolated or recently diverged lineages. This pattern extends to families with a single genus and higher ranks such as orders, where monotypic examples are less frequent but notable, like the mammalian order Tubulidentata, which comprises one family (Orycteropodidae), one genus (Orycteropus), and one species (Orycteropus afer, the aardvark).[22][13] Identification of monotypic taxa requires evidence that no additional subordinate taxa exist under prevailing taxonomic standards, typically involving comprehensive morphological, ecological, and distributional surveys. Phylogenetic analysis plays a central role in validation by reconstructing evolutionary relationships to confirm the absence of close relatives that might otherwise populate the taxon, ensuring monophyly and isolation within the hierarchy. Such analyses often incorporate molecular markers to delineate boundaries, with provisional monotypic status assigned when undescribed potential relatives are suspected but unconfirmed through ongoing research.[23][4] Challenges in determining monotypy arise from incomplete biodiversity inventories and the potential for hidden diversity, where molecular data such as DNA barcoding is essential for verification by assessing genetic divergence and intraspecific variation. In monotypic genera or rare taxa, limited sampling can obscure the barcode gap, necessitating comparisons with allied groups to establish distinctiveness. Retrospectively, discoveries of cryptic species—morphologically similar but genetically distinct entities—have split presumed monotypic taxa, as seen in the marine slug genus Pontohedyle, where molecular phylogenetics expanded a few recognized species into 12 cryptic lineages.[24][25] At higher ranks, such as monotypic orders, monotypy is rarer and more contentious owing to the expansive evolutionary scope involved, often reflecting ancient divergences with sparse fossil or extant relatives that complicate phylogenetic resolution. These cases demand robust evidence of deep isolation, yet they remain debated as new genomic data may reveal overlooked affinities or extinct branches.[23][4]Naming Conventions

The naming of monotypic taxa follows established codes that ensure stability and universality in biological nomenclature. For zoological taxa, the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) governs the process, particularly through provisions for type species designation in monotypic genera. Under Article 68.3 of the ICZN, if only one species-group nominal taxon is originally included in a genus-group nominal taxon, that species is automatically the type species (fixation by monotypy), providing a straightforward fixation without need for explicit designation.[26] This rule applies specifically to monotypic genera, where the single included species serves as the nomenclatural anchor. In botanical nomenclature, the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN; current edition: Madrid Code 2025) provides for type fixation in monotypic genera under Article 10, where the type species is fixed as the sole originally included species (see also Note 2), ensuring explicit type fixation is inherent in such descriptions. Additionally, ICN Article 11 mandates autonyms for nominotypical subdivisions of genera, automatically forming names identical to the parent genus for monotypic subdivisions without further action, with priority rules under Articles 11.3 and 11.5.[27][28] Specific practices for naming monotypic genera often involve deriving the genus name from the single species epithet, leading to tautonyms in zoology but not in botany. The ICZN permits tautonyms (e.g., Bison bison) under Article 31, allowing the species-group name to match the genus name as a noun in apposition or genitive, provided it complies with Latin grammatical rules.[29] In contrast, the ICN prohibits tautonyms via Article 23.4, requiring the specific epithet to differ from the generic name to avoid redundancy and promote distinctiveness. Explicit type fixation remains mandatory under both codes to prevent ambiguity, with the holotype or other name-bearing type specimen required for the species per ICZN Article 16.4 and ICN Article 40. Exceptions and updates to these conventions reflect evolving taxonomic needs. The 1999 fourth edition of the ICZN introduced greater flexibility for monotypic higher taxa by clarifying that names above the family-group rank (e.g., orders or classes) are not strictly regulated for type fixation, allowing monotypic higher taxa to be established without mandatory type species or genus designation if based on subordinate types. In botany, autonym formation extends to higher ranks; for a monotypic family based on a single genus, the family name matches the genus (e.g., Ginkgoaceae from Ginkgo), automatically via ICN Article 19 for nominotypical subfamilies. Recent developments include amendments at the 2017 Shenzhen International Botanical Congress (Shenzhen Code 2018) requiring registration in a repository for valid publication of new names, including monotypic ones, and the 2024 Madrid International Botanical Congress (Madrid Code 2025) making registration voluntary for plant and algal names to improve accessibility while not conditioning validity on it.[30] For zoology, the 2012 ICZN amendment (effective 2013) requires ZooBank registration for new names, including monotypic taxa, to validate electronic publications.[31] Common pitfalls in naming monotypic taxa often stem from inadequate literature review, leading to invalid names due to overlooked senior synonyms. For instance, proposing a new monotypic genus name that duplicates an earlier unused synonym can result in suppression or rejection under ICZN Article 23 or ICN Article 53, requiring later emendation.[32] Another frequent issue occurs upon discovery of additional species within a presumed monotypic genus; while the genus name persists with the original type species fixed, reclassification may necessitate name changes for the newly added species to resolve homonymy or priority conflicts, potentially destabilizing associated higher taxa if synonyms were missed.[33] Taxonomists mitigate these by conducting thorough synonymy checks and adhering to digital registration protocols to flag potential conflicts early.[34]Scientific Implications

Theoretical Aspects

Monotypic taxa pose significant theoretical challenges to taxonomic classification, particularly in the context of Linnaean hierarchy and set theory. Gregg's paradox, articulated in 1954, highlights the inconsistency inherent in defining monotypy across different taxonomic ranks, as the expectation of subordinate taxa varies by level, leading to redundant or identical sets in classifications where a higher taxon contains only one subordinate that itself lacks further subdivision.[19] This paradox arises because monotypic groupings violate the foundational principles of hierarchical classification, where each rank should provide distinct informational content; in practice, such taxa result in conceptual overlap, as the content of the monotypic higher rank mirrors that of its sole subordinate.[35] Conceptually, this can be framed as information loss within cladistic representations, where reduced branching in cladograms diminishes the number of diagnostic characters available for delimiting taxa, thereby complicating the resolution of evolutionary relationships.[7] In cladistic theory, monotypic taxa often emerge as potential aphyletic groups, lacking shared derived characters (synapomorphies) that define monophyletic assemblages, which raises debates about their status relative to paraphyly rules. Aphyly, as designated by Ebach and Williams in 2010, applies to such taxa that cannot be classified as monophyletic, paraphyletic, or polyphyletic due to insufficient evidence of phylogenetic structure, positioning monotypic entities as taxonomic "flotsam" that do not align with pattern-based cladistics. This perspective underscores ongoing controversies in pattern cladistics, where monotypic taxa challenge the requirement for demonstrable monophyly, potentially rendering them ineligible for inclusion in strict cladograms without additional character data.[36] From an evolutionary standpoint, monotypic taxa may signal undersampling in phylogenetic analyses or artifacts like long-branch attraction, where isolated lineages appear monotypic due to methodological biases in tree reconstruction rather than true biological singularity. Additionally, they can indicate scenarios of limited diversification, such as evolutionary stasis in relict lineages that have persisted without further speciation. A 2023 study by Vargas on monotypic genera frames them as markers of unique evolutionary histories, often representing ancient divergences with high lineage singularity, though this does not necessarily imply adaptive radiations but rather prolonged survival amid environmental changes.[37] Modern critiques further address rank-based ambiguities in monotypic classifications. Lücking (2019) argues for replacing "monotypic" with "monotaxonomic" to eliminate confusion, as the former misleadingly implies the presence of subordinate taxa while every taxon inherently contains a single type specimen; this terminological shift aims to clarify that monotypy at higher ranks stems from arbitrary hierarchical decisions rather than biological reality.[38] In phylogenomics, advancing genomic datasets increasingly dissolve apparent monotypy by revealing cryptic diversity or reassigning taxa, challenging the persistence of such categories in contemporary systematics.[39]Conservation Concerns

Monotypic taxa face elevated extinction risks compared to polytypic groups due to their unique evolutionary positions and limited representation within higher taxa. According to an analysis of IUCN Red List data, 6.56% of monotypic amphibian genera (8 out of 122) are classified as critically endangered, while 2.43% of monotypic bird genera (22 out of 904) hold this status, highlighting disproportionate vulnerability in these lineages.[37] Furthermore, approximately 80% of recently extinct bird genera were monotypic and endemic to islands, underscoring the role of isolation in amplifying extinction probabilities.[40] Several factors exacerbate these risks for monotypic taxa. Limited genetic diversity often leads to inbreeding depression, reducing fitness and adaptive capacity in small populations.[41] Ecological specialization, such as habitat restriction to narrow niches, further heightens susceptibility to perturbations, as these taxa lack the buffering provided by congeneric species.[42] Human impacts, particularly habitat loss and fragmentation, are amplified in monotypic groups, where the disappearance of a single species equates to the loss of an entire genus, accelerating biodiversity erosion.[43] Conservation strategies emphasize the prioritization of monotypic taxa to preserve unique evolutionary lineages. The IUCN Red List integrates monotypic status into risk assessments, facilitating targeted actions; for instance, the monotypic palmchat (Dulus dominicus) receives focused monitoring due to its isolated phylogenetic position despite a least concern status. Captive breeding programs have proven vital for monotypic mammals, such as the black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes), where intensive efforts averted extinction through population recovery from near-total loss.[44] These approaches align with the Convention on Biological Diversity's post-2020 framework, which calls for safeguarding evolutionarily distinct species to maintain phylogenetic diversity.[45] Recent trends indicate worsening threats, with 2025 assessments showing climate change intensifying risks for island endemics through habitat shifts and extreme events.[46] Research gaps persist, particularly in fungal and archaeal monotypic taxa, where up to 83% of ectomycorrhizal fungi remain "dark taxa" unlinked to described species, complicating conservation planning.[47]Notable Examples

In Plants

In the plant kingdom, monotypic taxa are exemplified by the genus Welwitschia, which contains only the species Welwitschia mirabilis, a gymnosperm endemic to the hyperarid Namib Desert spanning Namibia and Angola. This plant belongs to the monotypic family Welwitschiaceae and the monotypic order Welwitschiales, highlighting its isolated evolutionary position within the Gnetophyta division.[48] W. mirabilis exhibits remarkable adaptations to its extreme environment, including a deep taproot system accessing groundwater and two persistent, strap-like leaves that elongate indefinitely from a basal meristem, enabling survival in coastal fog-dependent niches with minimal rainfall.[49] Its extreme longevity, with individuals estimated to live over 1,500 years (up to 3,000 years in some cases) based on radiocarbon dating of woody tissues, underscores its status as a "living fossil" with a fossil record dating back 112 million years.[50] The taxonomic status of Welwitschia mirabilis as the sole species in its genus is upheld by the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN), which governs botanical naming and confirms its placement without recognized congeners. Recent molecular studies post-2010, including phylogeographic analyses using chloroplast and nuclear markers, support this monotypy while revealing subtle genetic divergence consistent with two subspecies (W. mirabilis subsp. mirabilis and subsp. namibiana), though these do not warrant species-level separation amid debates over cryptic diversity.[48] A 2021 chromosome-level genome assembly further elucidates its unique biology, showing genome duplication events that enhance resilience but affirming no additional species within the genus.[49] Conservation concerns for Welwitschia mirabilis are acute, with populations facing high extinction risk due to habitat degradation from mining, off-road vehicle traffic, and climate-driven desertification in the Namib.[51] Although not formally assessed by the IUCN globally, localized studies classify northern populations as endangered (EN) under IUCN criteria, emphasizing threats from illegal collection for horticulture and herbivory by porcupines and donkeys, which exacerbate slow regeneration rates.[51][50]In Animals

In the realm of vertebrates, the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) stands as a prominent example of a monotypic taxon, representing the sole extant species within the family Ornithorhynchidae and the order Monotremata alongside echidnas.[52] This semi-aquatic mammal, endemic to eastern Australia and Tasmania, exemplifies archaic mammalian traits such as egg-laying reproduction and electroreception via its bill, traits that link it to early mammalian ancestors from over 100 million years ago.[53] Similarly, the aardvark (Orycteropus afer) is the only living species in the order Tubulidentata, a lineage characterized by its specialized myrmecophagous diet and fossorial lifestyle across sub-Saharan Africa.[13] Among invertebrates, the chambered nautilus (Nautilus pompilius) serves as the iconic survivor in the order Nautilida, which contains the family Nautilidae with two genera (Nautilus and Allonautilus), with its external shell and pinhole camera eye preserving a body plan little changed since the Devonian period approximately 400 million years ago.[54] These cephalopods, distributed in Indo-Pacific depths, are often termed living fossils due to their morphological stasis compared to the diverse fossil nautiloids that dominated ancient seas.[55] In the microfaunal world, tardigrades like Ramazzottius varieornatus illustrate monotypic contexts within certain eutardigrade lineages, where this species' extremotolerance—enduring desiccation, radiation, and temperature extremes—positions it as a singular model for genomic studies of resilience in isolated evolutionary branches.[56] Evolutionary highlights of these taxa underscore their unique histories: monotremes such as the platypus retain primitive features like a cloaca and venomous spurs in males, bridging reptilian and mammalian physiologies in a lineage that diverged around 166 million years ago.[52] Nautiluses, by contrast, embody molluscan antiquity, with their biomineralized shells and jet propulsion evoking Paleozoic cephalopods while adapting to modern deep-sea niches.[57] Recent genomic sequencing in the 2020s, including the full Nautilus pompilius genome, has reinforced the isolation of living nautiloids by revealing conserved developmental genes despite a rich fossil record of extinct relatives, emphasizing genetic isolation over millions of years.[57] These animals face heightened conservation risks, including habitat loss and exploitation, amplifying the urgency to protect their singular evolutionary legacies.[13]In Other Organisms

Monotypic taxa occur across diverse non-plant and non-animal kingdoms, particularly among protists, fungi, and prokaryotes, where they often highlight unique evolutionary adaptations or sampling limitations in microbial ecosystems. In protists, the phylum Picozoa was initially described as monotypic, consisting solely of the species Picomonas judraskeda, a heterotrophic picoeukaryote isolated from freshwater environments and characterized by its novel cell motility, ultrastructure, and phylogenetic isolation from other eukaryotes; however, recent environmental sequencing (as of 2024) reveals significant undescribed diversity with numerous operational taxonomic units.[58][59] Among ciliates, the genus Parasincirra represents a monotypic taxon with Parasincirra sinica as its only species, distinguished by three frontal cirri and an amphisiellid median cirral row of comparable length to the adoral zone of membranelles, as revealed through morphological and molecular analyses.[60] Fungal monotypic taxa are prevalent in Ascomycota, such as the genus Dactyliodendromyces, which includes only Dactyliodendromyces sedimenticola, a marine-derived fungus identified through multi-locus phylogenetic analysis and phenotypic traits like its dendroid conidiophores.[61] Bacterial examples include the monotypic genus Nitriliruptor, encompassing Nitriliruptor alkaliphilus, a haloalkaliphilic, non-motile actinobacterium from soda lake sediments that degrades aliphatic nitriles.[62] In archaea, Nanoarchaeum equitans stands as the sole species in the genus Nanoarchaeum and the phylum Nanoarchaeota, an obligate parasitic hyperthermophile with a reduced genome that depends on its host Ignicoccus for metabolic functions.[63] Microbial monotypy in these groups often stems from the challenges of culturing unculturable diversity, where molecular surveys reveal vast undetected lineages, resulting in taxa appearing monotypic based on limited isolates.[64] Studies on extremophiles, including those from 2023, reinforce the monotypic status of certain lineages through integrated genomic and ecological data, emphasizing their specialized adaptations to harsh environments, while highlighting emerging diversity in others like Picozoa.[65]References

- https://www.antwiki.org/wiki/Monotypic_Taxa