Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hipparion

View on Wikipedia

| Hipparion Temporal range: Late Miocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton on display at the National Natural History Museum of China | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Equidae |

| Subfamily: | Equinae |

| Tribe: | †Hipparionini |

| Genus: | †Hipparion De Christol, 1832 |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

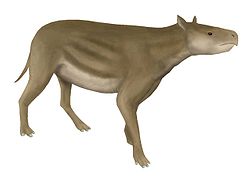

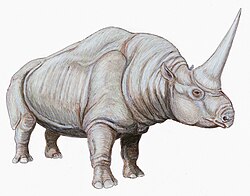

Hipparion is an extinct genus of three-toed, medium-sized equine belonging to the extinct tribe Hipparionini, which lived about 10-5 million years ago.[1][2] While the genus formerly included most hipparionines, the genus is now more narrowly defined as hipparionines from Eurasia spanning the Late Miocene.[2] Hipparion was a mixed-feeder who ate mostly grass, and lived in the savannah biome.[2][3] Hipparion evolved from Cormohipparion,[2] and went extinct due to environmental changes like cooling climates and decreasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.[4]

Taxonomy

[edit]"Hipparion" in sensu lato

[edit]The genus "Hipparion" was used for over a century as a form classification to describe over a hundred species of Holartic hipparionines from the Pliocene and Miocene eras that had three toes and isolated protocones. Since then, groups such as the genera Cormohipparion and Neohipparion were proposed to further sort these species, typically based on differences in skull morphology. These species are now known as "Hipparion" in sensu lato (s.l.), or a broad sense.[5]

Hipparion in sensu stricto

[edit]Hipparion in sensu stricto (s.s.), or a strict sense, describes the genus of Old World hipparionines from remains found in Eurasia (France, Greece, Turkey, Iran, and China) from the Late Miocene era (~10-5 Ma, or million years ago). The assignment of remains from elsewhere to the genus, such as North America and Africa, is uncertain.[2]

Morphology

[edit]

Hipparion generally resembled a smaller version of the modern horse, but was tridactyl, or three-toed. It had two vestigial outer toes on each limb in addition to its hoof.[2] In some species, these outer toes were functional.[6] Hipparion was typically medium in size, at about 1.4 m (4.6 ft) tall at the shoulder.[7][8] The estimated body mass of Hipparion depends on the species, but ranges from about 135 to 200 kg (about 298 to 441 lbs).[2] Hipparion had hypsodont dentition (high-crowned teeth) for its premolars and molars, with a crown height of about 60 mm (2.36 in). Hipparion had isolated protocones in the upper molars, meaning a cusp of the teeth called a protocone was not connected to a tooth crest called a protoloph.[2] Hipparion is also characterized by its facial fossa, or deep depression in the skull, located high on the head in front of the orbit.[9][10]

Paleobiology and paleoecology

[edit]

Hipparion lived in the Old World Savannah Biome, or OWSB, consisting of woodlands to grasslands.[2] Hipparion ate a mixed-feed diet, mostly consisting of grass. This diet is indicated by fossil evidence of microscopic wear patterns of scratches and pits on the enamel of Hipparion's teeth, observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).[3]

Hipparion achieved skeletal maturity and possibly sexual maturity at about 3 years old. Fossils of Hipparion individuals are up to 10 years old at death.[8]

Isotopic analysis indicates that in the late Miocene Batallones 3 fossil site in Spain, the sabertooth cats Promegantereon and Machairodus, the amphicyonids (bear-dogs) Magericyon and Thaumastocyon, the large mustelid Eomellivora and possibly the early omnivorous giant panda relativa Indarctos likely considerably predated upon Hipparion.[11]

Evolution and extinction

[edit]Hipparion likely evolved from a species of Cormohipparion during the Late Miocene, about 11.4–11.0 Ma. This species, C. occidentale, came to Eurasia and Africa from North America.[2] The last common ancestor of Hipparion and the modern horse was Merychippus.[12]

In the Old World, Hipparion experienced population decline and extinction down a North to South gradient, as did many other Miocene vertebrates. This trend is believed to be due to environmental changes caused by global cooling and decreasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere.[4]

Species

[edit]- H. chiai Liu et al., 1978

- H. concudense Pirlot, 1956

- H. condoni Merrian, 1915

- H. crassum Gervais, 1859

- H. dietrichi Wehrli, 1941

- H. fissurae Crusafont and Sondaar, 1971

- H. forcei Richey, 1948

- H. gromovae Villalta and Crusafont, 1957

- H. laromae Pesquero et al., 2006

- H. longipes Gromova, 1952

- H. lufengense Sun, 2013

- H. macedonicum Koufos, 1984

- H. matthewi Abel, 1926

- H. mediterraneum Roth and Wagner, 1855

- H. molayanense Zouhri, 1992

- H. minus Pavlow, 1890

- H. periafricanum Villalta and Crusafont, 1957

- H. philippus Koufos & Vlachou, 2016

- H. phlegrae Lazaridis and Tsoukala, 2014

- H. prostylum Gervais, 1849 (type)

- H. rocinantis Pacheco, 1921

- H. sellardsi Matthew and Stirton, 1930

- H. shirleyae MacFadden, 1984

- H. sithonis Koufos & Vlachou, 2016

- H. sitifense Pomel, 1897

- H. tchicoicum Ivanjev, 1966[13]

- H. tehonense (Merriam, 1916)

- H. theniusi Melentis, 1969

- H. venustum Leidy, 1860

References

[edit]- ^ Cirilli, Omar; Pandolfi, Luca; Alba, David M.; Madurell-Malapeira, Joan; Bukhsianidze, Maia; Kordos, Laszlo; Lordkipanidze, David; Rook, Lorenzo; Bernor, Raymond L. (2023-04-15). "The last Plio-Pleistocene hipparions of Western Eurasia. A review with remarks on their taxonomy, paleobiogeography and evolution". Quaternary Science Reviews. 306 107976. Bibcode:2023QSRv..30607976C. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.107976. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bernor, Raymond L.; Kaya, Ferhat; Kaakinen, Anu; Saarinen, Juha; Fortelius, Mikael (October 2021). "Old world hipparion evolution, biogeography, climatology and ecology". Earth-Science Reviews. 221 103784. Bibcode:2021ESRv..22103784B. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103784.

- ^ a b MacFadden, Bruce J. (2000). "Cenozoic Mammalian Herbivores of the Americas: Reconstructing Ancient Diets and Terrestrial Communities" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 31 (1): 33–59. Bibcode:2000AnRES..31...33M. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.33.

- ^ a b van der Made, Jan; Boulaghraief, Kamel; Chelli-Cheheb, Razika; Cáceres, Isabel; Harichane, Zoheir; Sahnouni, Mohamed (Jan 28, 2022). "The last North African hipparions – hipparion decline and extinction follows a common pattern". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. 303 (1): 39–87. Bibcode:2022NJGPA.303...39V. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2022/1037 – via Schweizerbart Science Publishers.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J. (August 1980). "The Miocene horse Hipparion from North America and from the type locality in Southern France". Palaeontology. 23 (3): 617–635 – via The Paleontological Association.

- ^ Williams, Wendy (2015). The Horse. Toronto, Canada: Harper Collins. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4434-1786-0.

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 257. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ a b Martinez-Maza, Cayetana; Alberdi, Maria Teresa; Nieto-Diaz, Manuel; Prado, José Luis (2014-08-06). "Life-History Traits of the Miocene Hipparion concudense (Spain) Inferred from Bone Histological Structure". PLOS ONE. 9 (8) e103708. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j3708M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103708. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4123897. PMID 25098950.

- ^ Bernor, Raymond L.; Kovar-Eder, Johanna; Lipscomb, Diana; Rögl, Fred; Sen, Sevket; Tobien, Heinz (1988-12-14). "Systematic, stratigraphic, and paleoenvironmental contexts of first-appearing Hipparion in the Vienna Basin, Austria". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 8 (4): 427–452. Bibcode:1988JVPal...8..427B. doi:10.1080/02724634.1988.10011729. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Carroll, Robert L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 535. ISBN 0-716-71822-7.

- ^ Domingo, M. Soledad; Domingo, Laura; Abella, Juan; Valenciano, Alberto; Badgley, Catherine; Morales, Jorge (August 2016). "Feeding ecology and habitat preferences of top predators from two Miocene carnivore-rich assemblages". Paleobiology. 42 (3): 489–507. Bibcode:2016Pbio...42..489D. doi:10.1017/pab.2015.50. hdl:10261/136983. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ Cantalapiedra, J. L.; Prado, J. L.; Hernández Fernández, M.; Alberdi, M. T. (2017-02-10). "Decoupled ecomorphological evolution and diversification in Neogene-Quaternary horses". Science. 355 (6325): 627–630. Bibcode:2017Sci...355..627C. doi:10.1126/science.aag1772. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28183978.

- ^ Kalmykov N. P. (2023). "New Data on Dental Morphology of Hipparion tchicoicum Ivanjev, 1966 from Western Transbaikalia, Russia". Dokl Biol Sci. 508 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1134/S001249662270017X. PMID 37186049.