Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hour record

View on WikipediaThe hour record is the record for the longest distance cycled in one hour on a bicycle from a stationary start. Cyclists attempt this record alone on the track without other competitors present. It is considered one of the most prestigious records in cycling. Since it was first set, cyclists ranging from relatively unknown amateurs to well-known professionals have held the record. There is now one unified record for upright bicycles meeting the requirements of the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI). Hour-record attempts for UCI bikes are made in a velodrome.

Early hour records (until 1972)

[edit]

The first universally accepted record was in 1876 when the American Frank Dodds rode 26.508 km (16.471 mi) on a penny-farthing.[1] The first recorded distance[2] was set in 1873 by James Moore in Wolverhampton, riding an Ariel 49" high wheel (1.2 m) bicycle; however, the distance was recorded at exactly 14.5 miles (23.3 km), leading to the theory that the distance was just approximated and not accurately measured.[3]

The first officially recognised record was set by Henri Desgrange at the Buffalo Velodrome, Paris in 1893 following the formation of the International Cycling Association, the forerunner of the modern-day UCI. Throughout the run up to the First World War, the record was broken on five occasions by Swiss rider Oscar Egg and Frenchman Marcel Berthet, and due to the attempts being highly popular and guaranteeing rich attendances, it is said that each ensured he did not beat the record by too much of a margin, enabling further lucrative attempts by the other.[nb 1]

The hour was attempted sporadically over the following 70 years, with most early attempts taking place at the Buffalo Velodrome in Paris, before the Velodromo Vigorelli in Milan became popular in 1930s and 1940s sparking attempts from leading Italian riders and former Giro d'Italia winners such as Fausto Coppi and Ercole Baldini. Coppi's record set in 1942, during the Second World War, despite Milan being bombed nightly by Allied forces, was eventually broken in 1956 by Jacques Anquetil on his third attempt. In 1967, 11 years later, Anquetil again broke the hour record, with 47.493 km (29.511 mi), but the record was disallowed because he refused to take the newly introduced post-race doping test.[4] He had objected to what he saw as the indignity of having to urinate in a tent in front of a crowded velodrome and said he would take the test later at his hotel. The international judge ruled against the idea, and a scuffle ensued that involved Anquetil's manager, Raphaël Géminiani. In 1968, Ole Ritter broke the record in Mexico City, the first attempt at altitude since Willie Hamilton in 1898.[citation needed]

The women's hour record was first established in 1893 by Mlle de Saint-Sauveur at the Vélodrome Buffalo in Paris, setting a total distance of 26.012 km (16.163 mi). The record was improved several times over the next years, until Louise Roger reached 34.684 km (21.552 mi) in 1897 also at Vélodrome Buffalo.[5] In 1911 the longest standing men's or women's record (37 years) was set by the 157 cm (5 ft 2 in) tall Alfonsina Strada: 37.192 km (23.110 mi) riding a 20 kg (44 lbs) machine.[6][7] From 1947 to 1952, Élyane Bonneau and Jeannine Lemaire set several new hour records, the last of which was 39.735 km (24.690 mi) by Lemaire in 1952.[8][9] The first women's hour record approved by the UCI was by Tamara Novikova in 1955. However Lemaire's 1952 non-UCI record was not bettered until Elsy Jacobs broke the 40 kmh barrier in 1958, the year Jacobs had won the inaugural women's road world championship. Jacobs' 1958 41.347 km UCI record would not be bettered until 1972.

Historical hour records

[edit]

|

|

UCI hour record (1972–2014)

[edit]1972–1984: Merckx, Moser and new technology

[edit]

In 1972, Eddy Merckx set a new hour record at 49.431 km (30.715 mi) in Mexico City at an altitude of 2,300 m (7,500 ft) where he proclaimed it to have been "the hardest ride I have ever done".[12]

The record stood until January 1984, when Francesco Moser set a new record at 51.151 km (31.784 mi). This was the first noted use of disc wheels, which, along with Moser's skin suit, provided aerodynamic gains. Moser's record would eventually be moved in 1997 to "best human effort".[12]

1990s: non-traditional riding positions

[edit]In 1993 and 1994, Graeme Obree, who built his own bikes, posted two records with his hands tucked under his chest. In 1994, Moser set the veteran's record in Mexico City, riding 51.840 km (32.212 mi)[13] with bullhorn handlebars, steel airfoil tubing, disk wheels and skinsuit. Moser's distance beat his 1984 record and Obree's 1993 ride.

In May 1994, the UCI outlawed the "praying mantis" style. Spaniard Miguel Induráin and Swiss Tony Rominger subsequently broke the record with a more traditional tri-bar setup; Rominger rode 55.291 km.

Chris Boardman took up the challenge using a modified version of the Lotus 110 bicycle, a successor to the earlier Lotus 108 bicycle he'd ridden to victory at the 1992 Olympic Games. South African company Aerodyne Technology built the frame. Boardman set the UCI Absolute record of 56.375 km (35.030 mi) in 1996, using another position pioneered by Obree, his arms out in front in a "Superman" position. This too was considered controversial by the UCI, and while the record was allowed to stand, the position was banned. This enabled Boardman's 1996 record to stand for about 26 years. In October 2022, Filippo Ganna unified the records, beating Boardman's best human effort record and Daniel Bigham's official UCI Hour record on a traditionally shaped, though uniquely manufactured, bicycle.[12]

1997 UCI rule change

[edit]With the increasing gap between modern bicycles and what was available at the time of Merckx's record, the UCI established two records in 1997:

- UCI Hour Record: which restricted competitors to roughly the same equipment as Merckx, banning time trial helmets, disc or tri-spoke wheels, aerodynamic bars, and monocoque frames.

- Best Human Effort: also known as the UCI "Absolute" Record[12] in which modern equipment was permitted.

As a result of the 1997 rule change, all records since 1972, including Boardman's 56.375 km (35.030 mi) in 1996, were moved to Best Human Effort and the distance of Eddy Merckx set in 1972 once more became the official UCI benchmark. In 2000, Boardman attempted the UCI record on a traditional bike, and rode 49.441 km (30.721 mi), topping Merckx by 10 metres (32.8 ft), an improvement of 0.02%.

In 2005, Ondřej Sosenka improved Boardman's performance at 49.700 km (30.882 mi) using a 54×13 gear. However, Sosenka failed a doping control in 2001 and then again in 2008, the latter resulting in a career-ending suspension which puts in doubt the validity of his record. All women's records from 1986 to 1996 were recategorized to Best Human Effort.

Hour record holders (men's)

[edit]

|

|

Hour record holders (women's)

[edit]

|

|

UCI unified hour record (2014–present)

[edit]Unified rule change (2014)

[edit]

In 2014, the UCI unified the two classifications into a single classification in line with regulations for current track pursuit bikes. Records previously removed for Chris Boardman and Graeme Obree were returned, however the benchmark record would remain at 49.7 km (30.9 mi) set in 2005 by Ondrej Sosenka, even though that was not the farthest distance.[26][27] Under the new regulations riders may use any bike allowed by the UCI standards for endurance track events in place at the time of the attempt.[28]

Riders are required to be part of the athlete biological passport program.[29] However, of the men to attempt the record since the rule change, only five were on a UCI World Tour team at the time: Jens Voigt of Trek Factory Racing,[30] Rohan Dennis of the BMC Racing Team, Alex Dowsett of the Movistar Team, Victor Campenaerts of Lotto Soudal, Filippo Ganna of Ineos Grenadiers. Matthias Brändle was with IAM Cycling, then a UCI Professional Continental team. Jack Bobridge was on Team Budget Forklifts, an Australian UCI Continental team. Thomas Dekker had been released from World Tour team Garmin–Sharp several months before. Gustav Larsson was riding for the Professional Continental team Cult Energy Pro Cycling, whilst Bradley Wiggins had left the World Tour's Team Sky shortly before his attempt, which was made in the colours of his own UCI Continental team WIGGINS.

As of October 2022, 26 attempts have been made for the men's record, eight successfully, while nine attempts have been made on the women's record, six of them successfully.

Unified hour record attempts (men's)

[edit]Following the change in the rules, German Jens Voigt became the first rider to attempt the hour, on 18 September 2014 at the Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland.[31][32] He set a new record of 51.110 km (31.758 mi), beating the previous record set by Sosenka by 1.41 km (0.88 mi).[12] On 30 October 2014, Matthias Brändle set a new record of 51.852 km (32.219 mi) at the World Cycling Center in Aigle, Switzerland.

Further attempts by Australians Jack Bobridge and Rohan Dennis, and the Dutchman Thomas Dekker came within a few weeks, between 31 January and 25 February 2015. Dennis was the only one of the three to set a new record, and in doing so was the first rider to cover more than 52 kilometres (32.3 mi). Dekker's attempt at the Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome was the first attempt to take place at appreciable altitude. Aguascalientes is at 1,890 m (6,200 ft) above sea level, while Melbourne is at only 31 m (102 ft), and, although in Switzerland, Grenchen and Aigle are at 451 m (1,480 ft) and 415 m (1,362 ft) respectively, and not in the mountains. High altitude is thought to result in faster times, providing the rider takes the time to acclimatise to the conditions.[33] This is because the air density decreases with an increase in altitude, which reduces the aerodynamic drag.[34]

Having postponed an earlier scheduled attempt due to a broken collarbone incurred in a crash while training, British cyclist Alex Dowsett exceeded Dennis's mark, with a new record of 52.937 km (32.894 mi), at Manchester Velodrome on 2 May 2015.[35]

On 7 June 2015, Sir Bradley Wiggins broke Dowsett's record, by completing a distance of 54.526 km (33.881 mi) at the Lee Valley VeloPark in London.[36]

On 16 April 2019, Victor Campenaerts was the first to exceed 55 km/h by completing a distance of 55.089 km (34.231 mi) at the Velodromo Bicentenario in Aguascalientes.[37]

The UCI rules require an athlete to participate in its anti-doping system, including having a biological passport. When Daniel Bigham rode 54.723 km (34.003 mi) to break Wiggins's British national record on 1 October 2021[38] he was ineligible to attempt the UCI record as he was not part of the anti-doping system, estimating it would cost him £8,000.[39]

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 September 2014 | 43 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 51.110 (New record) |

Triathlon handlebar, Trek carbon fibre tubing frame, disc wheels,[41] chain on a 55/14 gear ratio.[42] | |||

| 30 October 2014 | 24 | World Cycling Centre Aigle, Switzerland (altitude 380m) | 51.852 (New record) |

Triathlon handlebar, SCOTT carbon fibre tubing frame, disc wheels, chain on a 55/13 gear ratio.[42] | |||

| 31 January 2015 | 24 | Darebin International Sports Centre, Melbourne, Australia | 51.300 (Failure) |

Triathlon handlebar, Cervelo carbon fibre tubing frame, disc wheels. | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 8 February 2015 | 24 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 52.491 (New record) |

Triathlon handlebar, BMC carbon fibre tubing frame, disc wheels, chain on a 56/14 gear ratio.[46] | |||

| 25 February 2015 | 30 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 52.221 (Failure) |

Koga TeeTeeTrack with Mavic Comete Track wheels, Koga components, Rotor cranks with a KMC (3/32") chain on a 58/14 gear ratio.[48] | First attempt at altitude (2000 m). Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 14 March 2015 | 34 | Manchester Velodrome, Manchester, United Kingdom | 50.016 (Failure) |

Ridley carbon track bike with front and rear disc wheels, triathlon handlebars. | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 2 May 2015 | 26 | Manchester Velodrome, Manchester, United Kingdom[51] | 52.937 (New record) |

Canyon Speedmax WHR carbon track bike, with Campagnolo Pista disc wheels, Pista crankset with 54 or 55 or 56t chainring.[52][53] | |||

| 7 June 2015 | 35 | Lee Valley VeloPark, London, United Kingdom[54] | 54.526 (New record) |

Pinarello Bolide HR, SRAM Crankset,[55] modified front fork, custom printed handlebars,[56] 58/14 gear ratio.[57] | Set CURRENT sea-level world best. | ||

| 21 March 2016 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland | 48.255 (Failure) |

|||||

| 16 September 2016 | 37 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 53.037 (Failure) |

Modified Diamondback Serios time trial bike, fitted with special HED disc wheels[59] and a gearing of 53/13[60] | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 28 January 2017 | 31 | Ballerup Super Arena, Ballerup, Denmark[62] | (Failure) |

Argon 18 Electron Pro, Mavic Comete discs, SRM + Fibre-Lyte chain ring, and a gearing of 54/13 | Failed to set new hour record. Attempt voided for doping, after Madsen's consumption of a contaminated food supplement. | ||

| 25 February 2017 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland | 48.337 (Failure) |

RB1213 track bike with double DT Swiss disc wheels | ||||

| 2 July 2017 | 32 | Arena Pruszków, Pruszków, Poland | 49.470 (Failure) |

BMC Trackmachine TR01, Mavic Comete disc wheels, Custom Prinzwear TT Suit | |||

| 7 October 2017 | 18 | Odense Cykelbane, Odense, Denmark[65] | 52.311 (Failure) |

Giant trinity track bike, Mavic disc wheels | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 11 January 2018 | 32 | Ballerup Super Arena, Ballerup, Denmark[66] | 52.324 (Failure) |

Argon 18 Electron Pro, Mavic Comete discs, SRM + Fibre-Lyte chain ring, and a gearing of 54/13 | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 26 July 2018 | 33 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico[67] | 53.630 (Failure) |

Argon 18 Electron Pro, Mavic Comete discs, SRM + Fibre-Lyte chain ring, and a gearing of 54/13 | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 22 August 2018 | 29 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico[69] | 52.757 (Failure) |

Customized Giant Trinity road frame, with a gearing of 58/14 | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 4 October 2018 | 19 | Odense Cykelbane, Odense, Denmark[70] | 53.730 (Failure) |

Giant trinity track bike, Mavic disc wheels | Failed to set new hour record. | ||

| 16 April 2019 | 27 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico (altitude 1887m)[71] | 55.089 (New record) |

Ridley Arena Hour Record bike, 330mm custom handlebars, custom handlebar extensions specifically moulded for Campenaerts's forearms, F-Surface Plus aero paint, Campagnolo drivetrain, full carbon disc Campagnolo Ghibli wheels, C-Bear bottom bracket bearings.[72] | |||

| 13 August 2019 | 34 | Odense Cykelbane, Odense, Denmark[73] | 53.975 (Failure) |

Failed to set new hour record. | |||

| 6 October 2019 | 22 | Odense Cykelbane, Odense, Denmark[74] | 52.061 (Failure) |

Failed to set new hour record. | |||

| 18 September 2020 | 30 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 52.116 (Failure) |

||||

| 23 October 2020 | 32 | Milton, Canada[75] | 51.304 (Failure) |

||||

| 3 November 2021 | 33 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico (altitude 1887m)[76] | 54.555 (Failure) |

Factor Hanzo time trial bike (track version), Aerocoach Aten chainring with 61/13 gearing, Aerocoach Ascalon extensions, custom Vorteq skinsuit, HED Volo disc wheels, Izumi Super Toughness KAI chain[77] | Failed to set new hour record. Set new British national record. | ||

| 19 August 2022 | 30 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 55.548 (New record) |

Prototype Pinarello Bolide F HR 3D[78] | |||

| 8 October 2022 | 26 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 56.792 (New record) |

Pinarello Bolide F HR 3D, 64t chain ring, 14t rear sprocket, Princeton Carbonworks wheelset, custom Bioracer Katana suit[78] | Beat Boardman's Best Human Effort | ||

| 14 August 2025 | 28 | Konya Velodrome, Konya, Turkey (altitude 1200m) | 53.976 (Failure) |

Hope-Lotus HB.T[79] | Failed to set new hour record. |

Unified hour record attempts (women's)

[edit]

The last women's hour record before the unified rule change was set on 1 October 2003 by Leontien van Moorsel, with a distance of 46.065 km (28.623 mi).

In December 2014, it was announced that British Paralympian Sarah Storey would be the first woman to attempt the record following the unified rule change. She attempted the record on 28 February 2015 at Lee Valley Velo Park in London, setting new British, Para-Cycling and Masters Age 35–39 records but missing out on the Elite record with a distance of 45.502 km (28.274 mi).[80]

American Molly Shaffer Van Houweling broke the women's UCI Hour Record, riding a distance of 46.273 km (28.753 mi) on 12 September 2015 in Aguascalientes, Mexico.[81] Van Houweling had set three new US Hour Records in the year prior. The first was set on 15 December 2014, in Carson, California, with a distance of 44.173 km (27.448 mi). The second was set on 25 February 2015, in Aguascalientes with a distance of 45.637 km (28.358 mi). The third was set on 3 July 2015, also in Aguascalientes, with a distance of 46.088 km (28.638 mi). This last mark was also the Pan-American and World Masters Age 40–44 record at the time, and exceeded the distance of the UCI hour record of van Moorsel. However, it did not qualify as the UCI Hour Record because Van Houweling had only been enrolled in the athlete biological passport program for three and a half months prior to setting this record. The UCI requires that riders be enrolled in this program for 5–10 months before they are eligible to set this mark.[82][83] From 24 August 2015, Van Houweling was eligible to attempt the UCI Hour Record.[84]

In October 2015, Australian rider Bridie O'Donnell announced her intention to aim for the hour record in January 2016. She broke the women's hour at the Adelaide Super-Drome on 22 January 2016, riding 46.882 km (29.131 mi). She was aged 41 years. Her record was broken by American rider Evelyn Stevens in the next month - the new record was 47.980 km (29.813 mi), more than a kilometre nearer to the 50 km (31 mi) barrier.

Italian rider Vittoria Bussi, after two unsuccessful attempts on 7 October 2017[85] and on 12 September 2018, broke Stevens' world record by 27 metres riding 48.007 km (29.830 mi) on 13 September 2018.[86]

British cyclist Joss Lowden set a new world record on 30 September 2021 with a distance of 48.405 km (30.077 mi), beating the previous record by just under 400 metres,[87] and also surpassing Jeannie Longo's Best Human Effort distance. Lowden completed a total of 193 laps of the Tissot Velodrome in Grenchen, Switzerland.[88]

On October 13, 2023, Vittoria Bussi set the world record again, at the Velodromo Bicentenario in Mexico, with a 50.267km distance.[89]

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 February 2015 | 37 | Lee Valley VeloPark, London, United Kingdom | 45.502 (Failure) |

Ridley Arena Carbon track bike with triathlon bars, Pro rear disc wheel, front disk wheel, Shimano Dura-Ace groupset.[90] | Beat Yvonne McGregor's previous British national record of 43.689 set in April 2002. New C5 Para-record, New Masters Age 35–39 record.[91] | ||

| 12 September 2015 | 42 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico (altitude 1887m) | 46.273 (New record) |

Metromint Cycling | Cervelo T4 track bike with double Mavic Comete discwheels, running 56/14 gear ratio.[81][92] | Beat her own national record of 46.088 km set on 3 July 2015, also in Aguascalientes, Mexico. | |

| 22 January 2016 | 41 | Super-Drome, Adelaide, Australia | 46.882 (New record) |

Cervelo T4 track bike.[93] | Set a new World Record, new sea-level World Best and National Record, besting Anna Wilson's former Australian national record of 43.501 km (set on October 18, 2000).[94] | ||

| 27 February 2016 | 32 | OTC Velodrome, Colorado, United States of America (altitude 1840m) | 47.980 (New record) |

Specialized Shiv modified for the track, SRAM groupset with 53t or 54t chainrings, Zipp 900 front wheel, Zipp Super 9 rear disc, Bioracer skinsuit. | Beat American national record. Outdoor 333.3 meter banked cement track.[95][96][97] | ||

| 21 July 2017 | 32 | Avantidrome, Cambridge, New Zealand | 47.791 (Failure) |

Failed to beat the absolute hour record. Set CURRENT sea-level world's best. New Zealand national record.[98] | |||

| 7 October 2017 | 30 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 47.576 (Failure) |

Giant Trinity track bike with Walker Brothers double-disc wheels | Failed to beat the hour record. Beat Italian national record[85][99] | ||

| 13 September 2018 | 31 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico (altitude 1887m) | 48.007 (New record) |

Endura skin suit, HVMN Ketone, and Liv Bike [100] | Failed to beat the hour record one day before, abandoning after 40 minutes. Beat the hour record by 27 metres the next day.[86] | ||

| 30 September 2021 | 33 | Velodrome Suisse in Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 48.405 (New record) |

LeCol x McLaren Skinsuit, Poc Tempor Helmet Argon18 Electron Pro track frame, WattShop Cratus chainrings (64x15 gear ratio) and WattShop Pentaxia Olympic/Anemoi handlebars/extensions, FFWD Disc-T SL wheels (front and rear w/ 23c Vittoria Pista tyres). Lowden may have used an 8.5mm pitch chain supplied by New Motion Labs.[88] | Beat Vittoria Bussi's record by 398 metres, and Jeannie Longo's best human effort by 246 metres. | ||

| 23 May 2022 | 35 | Velodrome Suisse in Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 49.254 (New record) |

Trek Speed Concept, Bontrager Race Space handlebar, Zipp Sub 9 Track wheels, Bontrager Hilo XXX saddle, 58x14 gear ratio[101] | Beat Joscelin Lowden's record by 849 metres.[102] | ||

| 13 October 2023 | 36 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico (altitude 1887m) | 50.267 (New record)[89] |

Beat Ellen van Dijk's record by 1013 metres.[103] | |||

| 10 May 2025 | 37 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico (altitude 1887m) | 50.455 (New record) |

Beat her own record by 188 metres. |

Statistics

[edit]-

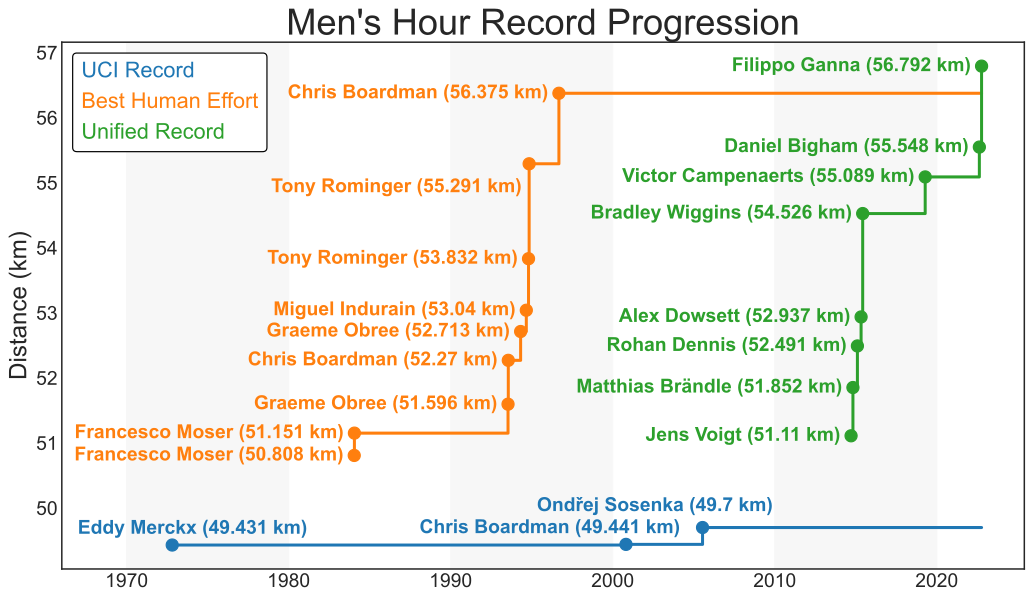

The above chart depicts the progression of the men's hour record over time (click to enlarge). Blue markers indicate attempts made under the UCI hour record, orange markers indicate attempts made under the UCI best human effort rules, and green markers indicate attempts made under the unified rules.

-

The above chart depicts the progression of the women's hour record over time (click to enlarge). Blue markers indicate attempts made under the UCI hour record, orange markers indicate attempts made under the UCI best human effort rules, and green markers indicate attempts made under the unified rules.

Para-cycling records

[edit]The new regulations for the making of accepted hour record attempts were extended to para-cycling in 2016.[104] Although the first attempt on the hour record for women after the amendments to the regulations was made by Paralympian Sarah Storey, it was not a ratified attempt on the women's C5 hour record under the new conditions, which at that point still did not extend to paracycling – albeit that Storey's effort is recognized as a best C5 performance under the new rules, in addition to a British and masters world hour record in able-bodied cycling.

The first attempt on a para-cycling hour record after the new regulations were extended to para-cycling was by Irishman Colin Lynch in the C2 category, bettering the accepted best performance previously set by Laurent Thirionet in 1999 by 2 kilometres, and setting the first 'ratified' para-cycling world hour record. The mark of 43.133 km was achieved on 1 October at the National Cycling Centre in Manchester, Great Britain.[104]

Men's UCI para-cycling hour record

[edit]- Unified regulations (since 2016)

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 December 2018 | 50 | Berlin, Germany | 42.583 | [106] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2016 | 45 | Manchester Velodrome, Manchester, England | 43.133 | ||||

| 16 July 2022[107] | 39 | Tissot Velodrome, Grenchen, Switzerland | 46.521 |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 August 2025[108] | 46 | Konya Velodrome, Konya, Turkey | 51.471 | First Para-cyclist in history go beyond 50km |

Women's UCI para-cycling hour record

[edit]- Unified regulations (since 2016)

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 February 2015 | 37 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 45.502 (New record) |

Historical para-cycling hour record

[edit]- Men's UCI para-cycling hour record – Best Hour Performance & Absolute Hour Record (1991–2016)

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 September 1991 | Bordeaux, France | 44.661 | Best Hour Performance | ||||

| 13 December 2014 | Montichiari Velodrome, Montichiari, Italy | 47.569 | Absolute Hour Record |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 September 1995 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 40.070 | Best Hour Performance | ||||

| 8 January 2005 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 41.817 | Best Hour Performance | ||||

| 14 February 2009 | Copenhagen, Denmark | 40.516 | Absolute Hour Record |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 November 1999 | Bordeaux, France | 41.031 | Best Hour Performance |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 May 2005 | 37 | Augsburg, Germany | 39.326 | Best Hour Performance |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 November 1994 | Moscow, Russia | 48.696 | Best Hour Performance | ||||

| 29 November 1997 | Bordeaux, France | 49.625 | Best Hour Performance |

- Women's UCI para-cycling hour record – Best Hour Performance & Absolute Hour Record (1991–2016)

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 February 2015 | Lee Valley VeloPark, England | 45.502 |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 September 2005 | Toireasa Gallagher |

Dunc Gray Velodrome, Sydney, Australia | 42.930 | Absolute Hour Record |

Masters records

[edit]Current records by age-group

[edit]| Age group | Male record [109] | Distance (KM) | Female record [110] | Distance (KM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30–34 | 50.686 | 41.564 | ||

| 35–39 | 51.599 | 42.425 | ||

| 40–44 | 51.228 | 47.061 | ||

| 45–49 | 51.623 | 47.080 | ||

| 50–54 | 51.013 | 44.427 | ||

| 55–59 | 51.061[111] | 45.213 | ||

| 60–64 | 47.430 | 42.194 | ||

| 65–69 | 47.220 | 40.416 | ||

| 70–74 | 43.216 | 38.191 | ||

| 75–79 | 38.903 | 36.352 | ||

| 80–84 | 39.836 | 27.447 | ||

| 85–89 | 34.602 | No record set | ||

| 90–94 | 34.498 | No record set | ||

| 95–99 | 20.151 | No record set | ||

| 100–104 | 26.925 | No record set | ||

| 105+ | 22.546 | No record set |

Men's UCI Masters best performances

[edit]- Best Performances

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 November 2004 | VELO Sports Center, Carson, United States of America | 47.764 (New record) |

[112] | |||||

| 29 July 2017 | Newport Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 48.234 (New record) |

[113] | |||||

| 24 September 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 45.325 (Failed) |

Failed to beat the previous hour record. Set a new national record.[114] | |||||

| 21 July 2019 | Arena Pruszków, Pruszków, Poland | 49.649(New record) | ||||||

| 18 August 2021 | Aguascalientes, Mexico | 50.094 (New record) |

[109] | |||||

| 15 September 2023 | Velodrome Suisse, Grenchen, Switzerland (altitude 450m) | 50.686 (New record) |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 April 2009 | Dunc Gray Velodrome, Sydney, Australia | 48.315 (New record) |

[115] | ||||

| 6 October 2015 | 39 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 48.743 (New record) |

[113] | |||

| 21 December 2017 | 38 | Cambridge, New Zealand | 48.922 (New record) |

[116] | |||

| 22 August 2019 | 39 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 51.599 (New record) |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 February 2013 | 43 | Dunc Gray Velodrome, Sydney, Australia | 48.411 (New record) |

[113] | |||

| 24 September 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 48.587 (New record) |

[114] | ||||

| 27 January 2020 | 40 | Melbourne Arena Melbourne, Victoria | 51.228 (New record) |

[109] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 September 1999 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 49.361 (New record) |

[113] | ||||

| 22 November 2016 | OTC Velodrome, Colorado, United States of America | 46.895 (Failed) |

Planet X track bike | Set a new Irish national hour record, beating the previous record of 46.166 of Tommy Evans – set in 1999 – by 729 metres[117] | |||

| 20 July 2017 | 47 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 47.458 (Failed) |

Peet's Coffee Cycling Team | [118] | ||

| 22 September 2018 | 47 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 50.245 (New record) |

||||

| 7 October 2020 | 46 | Velodrom Novo Mesto, Novo Mesto, Slovenia | 50.590

(New record) |

[109] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44.890 (New record) |

[119] | ||||||

| 10 December 2009 | 53 | Home Depot Center velodrome, Carson, United States of America | 45.386 (New record) |

[120] | |||

| 9 October 2012 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 47.960 (New record) |

[121] | ||||

| 4 October 2015 | 50 | Vélodrome National de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France | 45.799 (Failed) |

[121] | |||

| 6 November 2016 | 53 | Vélodrome National de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France | 48.892 (New record) |

[113] | |||

| 24 September 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 46.434 (Failed) |

Failed to beat the previous records. Set a new Canadian national record. | ||||

| 6 October 2017 | 54 | OTC Velodrome, Colorado, United States of America | 49.392 (New record) |

Argon 18 Electron Pro, Mavic Comet front and rear disc wheels, 53/13 gearing[122] | Set a new US Masters national hour record, beating the previous distance of 48.112 km (also held by Alvis). | ||

| 17 November 2017 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 48.469 (Failed) |

Planet X track bike | Set a new Irish national hour record, beating his own previous record of 46.860 km – set a year earlier in Colorado[123] | |||

| 29 September 2019 | 56 | OTC Velodrome, Colorado, United States of America | 49.383 (New record) |

||||

| 22 June 2022 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 51.013 (New record) |

[109] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 January 2012 | 57 | Home Depot Center velodrome, Carson, United States of America | 45.019 (New record) |

[120] | |||

| 19 March 2016 | 55 | Cambridge, New Zealand | 47.733 (New record) |

[113] | |||

| 20 July 2017 | 55 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 49.121 (New record) |

Peet's Coffee Cycling Team | [118] | ||

| 18 August 2021 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 49.387(New record) | [109] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61 | 44.228 (New record) |

[124] | |||||

| 30 September 2015 | 64 | Newport Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 44.349 (New record) |

Hounslow & District Wheelers | 49x14 gearing with a trispoke front and a rear disc, fitted with track tubulars[113][124] | ||

| 31 January 2020 | 60 | Arena Pruszków, Pruszków, Poland | 45.732 (New record) |

Alenka Žavbi Kunaver | S WORKS SHIV TT bike, VISION METRON track disk, BERK DILA seddle | Chainring 56, Track Cog 14 | |

| 29 April 2021 | 61 | Velodrom Novo Mesto, Novo Mesto, Slovenia | 46.255 (New record) |

Alenka Žavbi Kunaver | S WORKS SHIV TT bike, VISION METRON track disk, BERK DILA seddle | Chainring 57, Track Cog 14 | |

| 8 May 2021 | 60 | Cambridge, New Zealand | 47.360 (New record) |

[109] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 October 2012 | 65 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 43.742 (New record) |

[112] | |||

| 26 October 2016 | 65 | Newport Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 44.271 (New record) |

Hounslow & District Wheelers | [113] | ||

| 23 February 2020 | 66 | Dunc Gray Velodrome, Sydney, Australia | 44.62 (New record) |

[125] | |||

| 24 August 2024 | 65 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 44.662

(New Record) |

[139] | |||

| 8 February 2025 | 65 | Novo mesto Velodrome, Novo mesto, Slovenia | 46.142 (New record) |

Kolesarska zveza Slovenije | [126] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 September 2014 | 70 | Newport Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 41.227 (New record) |

[113] | |||

| 15 July 2017 | 70 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 43.216 (New record) |

[116] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33.000 (New record) |

[127] | ||||||

| October 2012 | 75 | Montichiari Velodrome, Montichiari, Italy | 35.728 (New record) |

[127] | |||

| 29 July 2014 | 75 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 38.494 (New record) |

[113] | |||

| 28 March 2022 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 38.903 (New record) |

[109] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 84 | Lee Valley VeloPark, London, United Kingdom | 28.388 (New record) |

London Cycling Campaign | Condor track bike | [128] | |

| October 2015 | SIT Velodrome, Southland, New Zealand | 29.187 (New record) |

[127][129][130] | ||||

| 29 October 2015 | 81 | Newport Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 35.772 (New record) |

Stourbridge Cycling Club | [127][129][131] | ||

| 25 June 2016 | 82 | Vélodrome National de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines,

Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France |

38.657 (New record) |

[113] | |||

| 20 August 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 38.334 (Failed) |

Marinoni bike, 53/14 gearing | [132] | |||

| 24 September 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 39.004 (New record) |

Marinoni bike, 53/14 gearing | [114] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 October 2016 | 87 | Vélodrome du Lac, Bordeaux, France | 34.095 (New record) |

[116] | |||

| 22 September 2019 | 85 | Newport Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 34.602 (New record) |

Stourbridge Cycling Club | [133] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 October 2017 | 90 | Vélodrome National de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines,

Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France |

29.278 (New record) |

Cyclosport Club de Vesoul | [134] | ||

| 6 August 2019 | 91 | OTC Velodrome, Colorado, United States of America | 34.498 (New record) |

[135] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 April 2019 | 96 | Cambridge, New Zealand | 20.886 (New record) |

Avantidrome Velodrome | [136] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 February 2012 | 101 | World Cycling Centre Aigle, Switzerland | 24.250 (New record) |

[137] | |||

| 31 October 2014 | 103 | Vélodrome National de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines,

Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France |

26.925 (New record) |

[113] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 January 2017 | 105 | Vélodrome National de Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines,

Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, France |

22.546 (New record) |

[113] |

Women's UCI Masters best performances

[edit]- Best Performances [110]

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 April 2012 | 30 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 41.564 (New record) |

[138] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 40.7556 (New record) |

[139][140] | ||||

| 14 March 2015 | 38 | Dunc Gray Velodrome, Sydney, Australia | 41.386 (New record) |

Midland Cycle Club | [139] | ||

| 14 May 2016 | 35 | Newport Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 42.116 (New record) |

SSLL Racing Team | Cervelo T4 track bike, Zipp disc wheels[141] | [138] | |

| 24 September 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 42.425 (New record) |

[142] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 July 2015 | 42 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 46.088 (New record) |

Metromint Cycling | Cervelo T4 track bike with double Mavic Comete discwheels, running 56/14 gear ratio. | [81][92] | |

| 14 July 2017 | 44 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 47.061 (New record) |

[138] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 September 2006 | Manchester Velodrome Manchester, England | 41.2397 (New record) |

[142][143] | ||||

| 24 September 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 38.156 (Failure) |

|||||

| 24 September 2018 | 46 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 46.897 (New record) |

[110] | |||

| 19 August 2019 | 47 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 47.080 (New record) |

[110] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 March 2011 | 51 | Montichiari Velodrome, Montichiari, Italy | 39.402 (New record) |

[138] | |||

| 26 March 2017 | 52 | Melbourne Arena Melbourne, Victoria | 43.206 (New record) |

[142] | |||

| 24 September 2017 | Mattamy National Cycling Centre, Milton, Canada | 40.366 (Failed) |

Failed to beat the previous record. Set a new national record.[114] | ||||

| 9 March 2018 | 53 | Melbourne Arena Melbourne, Victoria | 44.427 (New record) |

[110] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 October 2014 | 55 | VELO Sports Center, Carson, United States of America | 40.946 (New record) |

[138] | |||

| 27 January 2020 | 55 | Melbourne Arena Melbourne, Victoria | 43.963 (New record) |

||||

| 4 February 2022 | 57 | Melbourne Arena Melbourne, Victoria | 45.213 (New record) |

[110] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 October 2014 | 63 | VELO Sports Center, Carson, United States of America | 41.116 (New record) |

[138] | |||

| 7 April 2019 | 62 | Aguascalientes Bicentenary Velodrome, Aguascalientes, Mexico | 42.194 (New record) |

[110] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 March 2010 | 65 | Melbourne Arena Melbourne, Victoria | 37.214 (New record) |

[138] | |||

| 28 September 2017 | 66 | VELO Sports Center, Carson, United States of America | 38.191 (New record) |

[142] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 October 2018 | 72 | Cambridge, New Zealand | 36.581 (New record) |

[110] | |||

| 12 December 2021 | 71 | Los Angeles, United States of America | 40.416 (New record) |

[110] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 October 2014 | 75 | VELO Sports Center, Carson, United States of America | 27.894 (New record) |

[138] | |||

| 10 February 2019 | 75 | Melbourne Arena Melbourne, Victoria | 36.352 (New record) |

[110] |

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 September 2019 | 80 | VELO Sports Center, Carson, United States of America | 27.447 (New record) |

[144] |

Junior records

[edit]Although the UCI does not recognise hour record attempts at the Junior age-group, there have been multiple record attempts made.

| Date | Rider | Age | Velodrome | Distance (km) | Supported by | Equipment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 November 2016 | 17-18 | Colorado Springs, USA | 47.595 (New record) |

||||

| 29 September 2021 | 17 | Adelaide Super-Drôme, Adelaide, Australia | 48.480 (New record) |

Port Adelaide Cycling Club / South Australian Sports Institute | |||

| 14 March 2022 | 17 | Geraint Thomas National Velodrome, Newport, Wales | 49.184 (New record) |

Holohan Coaching Race Team | |||

| 17 October 2022 | 18 | Aguascalientes Velodrome, Mexico | 50.792 (New record) |

Other bicycle hour records

[edit]There are alternative bicycle hour records that do not fit the UCI-sanctioned categories due to a strict definition of a "bicycle" in UCI.[149][citation needed]

| Distance km | Rider | Gender | Hour record type | Comments | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 92.439 | Men's | HPV | Vehicle: Metastretto - designed by rider,[150] streamlined 2-wheeled recumbent, backwards ridden, mirror navigated. | 2016 | |

| 84.02 | Women's | HPV | 4th fastest person at the time. Vehicle: Varna Tempest - low-racer, 2-wheeled FWD, SWB, canopy bubble | 2009 | |

| 83.013 | Men's | HPV multi-rider, HPV tandem,

HPV tricycle. |

Vehicle: Cieo Tandem tricycle – Independent drivetrain, captain supine elevated above stoker – laying on back headfirst | 2013 | |

| 81.63 | Men's | HPV tricycle (single rider) | Vehicle: Phantom Mini-T – designed & built by Tim Corbett[151] | 2019 | |

| 66.042 | Women's | HPV tricycle | Vehicle: Varna 24 - Delta trike (two wheels in back), head bubble, FWD | ||

| 60.61 | Men's | HPV upright position | 1989 | ||

| 57.637 | Men's | Recumbent bike – Unfaired | Vehicle: Modified M5 highracer recumbent, SRM crankset. Estimated 325 watts power output. | 2016 | |

| 51.31 | Men's | Streamlined Enclosed Upright Bicycle | Titanium road racing bike with stretched fabric fairing by Chet Kyle. First "modern" HPV record. | 1979 | |

| 51.194 | Men's | Tandem | UK National Tandem. Unconfirmed as World Tandem Record. | 2003 | |

| 50.492 | Men's | Recumbent Tricycle – unfaired | Vehicle: Phantom Mini-T – Designed & built by Tim Corbett[152] | 2022 | |

| 46.946 | Men's | Madison Hour Record | Outdoor track, Vehicles: Fixed gear with aerobars | 2023 | |

| 46.7 | Men's | Road Time Trial (TT) Bike | Outdoor track, recorded on Strava. Vehicle: Trek Speed Concept | 2015 | |

| 44.749 | Men's | Arm Powered | Vehicle: Recumbent trike | 2019 | |

| 42.93 | Women's | Tandem open, Tandem paralympic | Visually-impaired stoker (Lindy Hou) | 2005 | |

| 38.154 | Men's | Cargo Utility Bike | Vehicle: Omnium – aerobars, rear 700c disk, front 20 inch, unloaded, wood platform removed due to windy conditions | 2018 | |

| 37.417 | Men's | No hands riding.

Mountain bike at altitude. |

Vehicle: Aluminium mountain bike | 2009 | |

| 35.258 | Women's | Ice tricycle (unfaired, recumbent) | Vehicle: Rear wheel powered, front skate steering, rear outrigger skate | 2015 | |

| 35.245 | Men's | Mountain bike (low altitude) | Outdoor, on hilly loop road. Vehicle: Mountain bike with knobby tires and aerobar, shirtless | 2006 | |

| 34.547 | Men's | Penny farthing | Unpaced. Also holds paced penny farthing record 35.743 km. (Penny farthing record rules allow pacing.) | 2019 | |

| 33.365 | Men's | Unicycle | Vehicle: geared 36" unicycle[153] | 2021 | |

| 30.95 | Men's | Wheelie (riding a bike on one wheel) | Outdoor[154] | 2020 | |

| 23.412 | Women's | Penny Farthing | Unpaced on the Jerry Baker Velodrome in Redmond, Washington USA | 2023 | |

| 20.294 | Men's | Penny Farthing, riding using one leg only | The left pedal was removed entirely from the penny farthing, ensuring that it could not be used. [155] | 2024 | |

| 19.76 | Men's | Riding using one leg only | Outdoor on road time trial bike | 2020 | |

| 19.3 | Men's | Wooden bike | Vehicle: Wooden bike built by himself and students, wood chain, 8 spokes, aerobar | 2016 | |

| 17.7 | Men's | PediCab/Ricksaw | No passenger | 2019 | |

| 0.918 | Women's | Slowest hour record | Requires gears, no fixed gear, no brakes, always moving forward. Tied with Davide Formolo in Pursuit-style race.[156] | 2021 | |

| 0.918 | Men's | Slowest hour record | Requires gears, no fixed gear, no brakes, always moving forward. Tied with Maria Sperotto in Pursuit-style race.[156] | 2021 |

Timing of the record

[edit]At the conclusion of the hour, the rider is inevitably part-way round a lap. They complete that lap (meaning they actually cycle for more than an hour). The distance completed in the hour is determined by adding the fraction of that final lap, calculated from the ratio of the time remaining at the start of that lap to the time taken for that lap, to the preceding completed laps.

Times are required to be measured to a thousandth of a second. Distances are rounded down to a complete metre and records can be beaten only by at least one metre.[157]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hutchinson, Michael (2007). The Hour. Penguin Random House. ISBN 9780224075206. (Michael Hutchinson. p. 119-120) It is reported that as professionals, Egg and Berthet ensured not to beat the record by too much of a distance, enabling them both to continue to repeatedly break the record and receive lucrative appearance fees

- ^ Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill (2011-10-16). The Historical Dictionary of Cycling. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810871755. (Jeroen Heijmans, Bill Mallon) lists three further records after Dodds but before Herbert Cortis. Listed only by surname, 1877, Shopee in Cambridge, 26.960, 1878, Weir, in Oxford, 28.542 and Christie, in 1879, 30.374, also in Oxford.

- ^ "Berthet/Egg Hour Record". Oscar Egg's original distance was recorded at 42.122 km. In July 1913 Richard Weise beat this mark, but following protest from Egg the Buffalo track was re-measured and his result changed to 42.360 km, cancelling out Weise's record

- ^ "The history of the recumbent bicycle". On 7 July 1933 Francis Faure rode 45.055 km on a "Velocar" beating Egg's record. This led to the UCI imposing rules regarding bicycle dimensions on 1 April 1934 and Faure's record was moved into a new category, "Records Set By Human Powered Vehicles (HPV's) without Special Aerodynamic Features"

- ^ Howard, Paul (2008). Sex Lies and Handlebar tape, p237-239. Mainstream Publishing Company, Limited. ISBN 9781845963019. (Paul Howard) Anquetil set a record time in 1967 of 47.493 km but the record was never ratified by the UCI following Anquetil's refusal to take a post race doping control, and on 13 October the UCI voted not to allow the record.

References

[edit]- ^ Mallon, Jeroen Heijmans, Bill (2011-09-09). Historical dictionary of cycling. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8108-7369-8. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2016-11-06.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill (2011-10-16). Historical Dictionary of Cycling. Scarecrow Press. p. 381. ISBN 9780810871755.

- ^ "Hour Record: The tangled history of an iconic feat". Cycling Weekly. 2015-04-15. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ^ Cycling 26 November 1987

- ^ Revolutionary Times – The Birth of the Women’s Hour Record Archived 2018-09-21 at the Wayback Machine – SB Nation's Podium Café, Feargal McKay, 11 September 2018

- ^ "Radio Marconi, Article on Alfonsina Strada". Archived from the original on 2012-02-16. Retrieved 2018-09-21.

- ^ Clemitson, Suze (2014-05-13). "Celebrating Alfonsina Strada, the woman who cycled the Giro d'Italia". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ^ "The BNA". Hull Daily Mail. 1947-10-25. Archived from the original on 2021-10-01. Retrieved 2021-10-01.

- ^ "Mlle Bonneau a battu le record du monde de l'heure". Le Monde. 1947-10-27. Archived from the original on 2021-10-01. Retrieved 2021-10-01.

- ^ "March 25 down the years". ESPN.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Meilleure Performance Sur Piste FSGT, https://www.cnav-club.fr/uploads/69/Record%20de%20l'heure%20%20FSGT%20Mars%202020.pdf Archived 2021-10-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Clemitson, Suze (19 September 2014). "Why Jens Voigt and a new group of cyclists want to break the Hour record". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Stephen Farrand (23 January 2014). "Gallery: Francesco Moser's hour record". Cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Chronic of the Hour Record". Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d "World Hour Records". Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Colnago, Ernesto (2004-03-19). "Ernesto Colnago 50th Anniversary Interview". cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-11. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ^ Laughlin, Ronan Mc (2022-06-21). "Retro tech: The TT bike that continues to define Pinarello". Velo. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ^ Simon Smythe (2015-12-12). "Icons of cycling: Miguel Indurain's Pinarello Espada". cyclingweekly.com. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ^ James, Martin (2022-02-09). "Colnago's classic bike collection". Cyclist. Retrieved 2023-06-02.

- ^ a b "Women Elite – World Records" (PDF). UCI.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Maria Cressari". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- ^ "Keetie Van Ooosten breaks hour record". pzc. 18 September 1978.

- ^ "Van Ooosten breaks hour record". pzc. 16 September 1978. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- ^ "Leontien van Moorsel breaks hour record". pzc. 2 October 2003. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- ^ "Bike Cult — Sports Records". bikecult. Archived from the original on 2015-01-24. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ "Hour Record rule change — Athlete's hour to be scrapped". Cycling Weekly. 15 May 2014. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "UCI changes hour record regulations, allows modern track bikes". VeloNews.com. 2014-05-15. Archived from the original on 2014-09-18. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "How the Hour Record Will Save Cycling". Outside Online. 2014-06-05. Archived from the original on 2014-09-24. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Cookson reveals that people have come forward to the CIRC Reform Commission". Cyclingnews.com. 23 May 2014. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Voigt breaks world hour record". Cycling News. 2014-09-18. Archived from the original on 2019-08-24. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

The Trek Factory Racing rider called an end to his road career at the USA Pro Challenge in Colorado in August, 2014, but soon announced his attempt at the record.

- ^ Giles Richards (2014-09-13). "The Agenda: Jens Voigt aims to break one of cycling's toughest records". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2014-09-17. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "Answered: 11 questions about Jens Voigt's hour record attempt". VeloNews.com. 2014-09-15. Archived from the original on 2014-09-18. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ CyclingTips (2015-01-07). "Dekker to bid for world hour record at altitude in Mexico at end of February". cyclingtips.com.au. Archived from the original on 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ "The Hour Record At Altitude". wolfgang-menn.de. Archived from the original on 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ "Alex Dowsett sets new Hour Record of 52.937km". Cycling News. 2 May 2015. Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "Bradley Wiggins breaks UCI Hour Record at Lea Valley VeloPark". BBC Sport. 7 June 2015. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Victor Campenaerts sets new UCI Hour Record". 2019-04-16. Archived from the original on 2019-04-16. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- ^ "Dan Bigham breaks Bradley Wiggins' British Hour Record". cyclingnews.com. October 2021. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "Dowsett: It's desperately unfair that Bigham can't go for official Hour Record". cyclingnews.com. 28 September 2021. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "Hour Record". www.trekbikes.com. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ "Voigt: I can't ask for a better goodbye". Cyclingnews.com. 10 September 2014. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Hour Record analysis: Matthias Brändle's big gear — Cycling Weekly". Cycling Weekly. 31 October 2014. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "IAM Cycling — Matthias Brändle and IAM Cycling take on the UCI Hour Record". iamcycling.ch. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ "Jack Bobridge set for Hour Record attempt". roadcycling.co.nz. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ Zeb Woodpower (31 January 2015). "Jack Bobridge Hour Record attempt 2015: Results — Cyclingnews.com". Cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Bike Cult Book: Online Resource: World Hour Records". bikecult.com. Archived from the original on 2015-01-24. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ "UCI Hour Record: Thomas Dekker's Koga TeeTeeTrack bike with 58x14 gearing". road.cc. 2015-02-25. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2015-02-26.

- ^ "Dekker on track for Hour Record attempt". Cyclingnews.com. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Gustav Larsson to attempt Hour Record at Revolution Series". Cyclingnews.com. 10 March 2015. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Gustav Larsson UCI Hour Record attempt. FACE Partnership. 14 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ "Alex Dowsett announces new Hour Record date". Cycling Weekly. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Alex Dowsett's Canyon Speedmax WHR (Video)". Cycling Weekly. 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ Tom Ballard / Immediate Media (May 2015). "Pro bike: Alex Dowsett's Canyon Speedmax WHR". Cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2015-05-02.

- ^ "Wiggins schedules hour record attempt for June 7". VeloNews.com. 2015-04-15. Archived from the original on 2015-04-18. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

- ^ "Bradley Wiggins' Pinarello Bolide HR – First glimpse of Hour Record bike". Cyclingnews.com. 28 May 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ "Bradley Wiggins' Pinarello Bolide HR". Cyclingnews.com. 5 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Velodrome, Luke Brown and John MacLeary at Lee Valley (7 June 2015). "Sir Bradley Wiggins hour record attempt: as it happened". Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ "Micah Gross établit un nouveau record suisse de l'heure – Swiss Cycling". www.swiss-cycling.ch. Archived from the original on 2017-10-26. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ "Zirbel to make Hour Record attempt this week". cyclingnews.com. September 12, 2016. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Tom Zirbel's Hour Record Diamondback Serios – Gallery". cyclingnews.com. September 16, 2016. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Zirbel sets new US Hour Record". cyclingnews.com. 16 September 2016. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Feltet.dk. "Martin Toft Madsen satte timerekord Feltet.dk". www.feltet.dk. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- ^ "New Swiss record of the hour for Marc Dubois – Humard Automation SA". www.humard.com. 2017-02-27. Archived from the original on 2017-10-26. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ Gruntkowski, Dawid (July 2, 2017). "Wojciech Ziółkowski z rekordem Polski w jeździe godzinnej!". Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ^ "Dansk stortalent slår timerekord". 7 October 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ^ "Ny dansk timerekord til Martin Toft Madsen". 11 January 2018. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Timerekord i Mexico: Mail bekræfter Toft-forsøg". 30 June 2018. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Record de l'Heure : Martin Toft Madsen échoue". Direct Velo. 26 July 2018. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ^ "Three riders to make UCI Hour Record timed by TISSOT attempts this summer". UCI. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Stortalent sætter dansk timerekord". 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- ^ "Campenaerts to attack Wiggins' Hour Record in April". 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-02-28. Retrieved 2019-02-27.

- ^ "Victor Campenaerts' Ridley Arena TT Hour Record – Gallery". 28 March 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-03-28. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ "Martin Toft Madsen slår den danske timerekord". 13 August 2019. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Ingen dansk timerekord til Mathias Norsgaard". feltet.dk. 6 October 2019. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Ironman triathlete Lionel Sanders sets Canadian record for distance cycled in an hour". CBC News. 23 October 2020. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ "Alex Dowsett falls short in UCI Hour Record attempt". CyclingNews. Future plc. 3 November 2021. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Dowsett reveals tech selections and power targets for Hour Record attempt". Cyclingnews. 2021-10-17. Archived from the original on 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ^ a b "€75k per hour – Filippo Ganna's full gear and kit list for his Hour Record attempt". 7 October 2022.

- ^ "British cyclist Charlie Tanfield falls short of Filippo Ganna's UCI Hour Record". 14 August 2025.

- ^ "Britain's Sarah Storey to tackle women's hour record". VeloNews.com. 2014-12-16. Archived from the original on 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2014-12-16.

- ^ a b c d "Molly Shaffer Van Houweling makes history with new women's UCI Hour Record". www.uci.ch. Archived from the original on 2015-09-14.

- ^ "Van Houweling sets Pan American Record". velonews. 2015-02-27. Archived from the original on 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Van Houweling sets Hour Record of 46,088m". norcalcyclingnews. Archived from the original on 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2015-07-06.

- ^ "News shorts: Gesink abandons Tour de Pologne with fatigue". Cyclingnews.com. 4 August 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ^ a b Cycling, UCI Track. "Hats off to @vittoria_bussi for her attempt to the #UCIHourRecord. 47,576 km, just 404 meters away from @evelyn_stevens record pic.twitter.com/nsLvfA9Smt". Archived from the original on 2021-11-24. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ^ a b "Vittoria Bussi breaks Evelyn Stevens's hour record". Velonews. 2018-09-14. Archived from the original on 2018-09-14. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ "Joss Lowden rides 48.405km in new world hour record". VeloNews.com. 2021-09-30. Archived from the original on 2021-09-30. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ a b Pitt, Vern; Smythe, Simon (2021-09-30). "Joss Lowden's Hour Record: the aero kit that could help make history". cyclingweekly.com. Archived from the original on 2021-09-30. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ a b Tom Davidson (14 October 2023). "Vittoria Bussi makes history with new UCI Hour Record". cyclingweekly.com.

- ^ Tom Ballard / Immediate Media (20 February 2015). "Pro bike: Dame Sarah Storey's hour record Ridley Arena Carbon". Cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Sarah Storey misses Hour Record by 563m". Cycling Weekly. 28 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "Molly Shaffer Van Houweling sets new women's World Hour Record | Ella". cyclingtips.com.au. 2015-09-13. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ^ "Bridie O'Donnell Hour Record attempt 2016: Results". Cyclingnews.com. January 22, 2016. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Bridie O'Donnell to attempt women's UCI Hour Record". Cyclingnews.com. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ^ "Evelyn Stevens to make UCI Hour Record attempt". Cyclingnews.com. February 8, 2016. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Media, Ben Delaney/Immediate (February 25, 2016). "Assembling Evelyn Stevens' hour-record attempt bike". cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ Frattini, Kirsten (February 27, 2016). "Evelyn Stevens Hour Record Attempt 2016: Results". cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Jaime Nielsen smashes sea level world record". 2017-07-21. Archived from the original on 2019-01-12. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- ^ "Record dell'Ora, l'italiana Vittoria Bussi si ferma a soli 404 metri da Evelyn Stevens – Cicloweb". 7 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Vittoria Bussi breaks Hour Record in second attempt within 48-hours". 2018-09-13. Archived from the original on 2018-09-18. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

- ^ Portus, Stan (23 May 2022). "Ellen van Dijk breaks hour record on custom Trek Speed Concept". bikeradar.com. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Weislo, Laura (24 May 2022). "Van Dijk smashes women's Hour Record". cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ^ "Vittoria Bussi reclaims the UCI Hour Record timed by Tissot and breaks the legendary 50-kilometre barrier". UCI.org. 2023-10-14. Retrieved 2023-11-01.

- ^ a b Colin Lynch makes para-cycling history Archived 2016-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, from Paralympic.org

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Para-cycling — About". uci.ch. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "Teuber smashes C1 Hour Record". 2 December 2018. Archived from the original on 2 December 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ "Para-cycling: new UCI Hour Record timed by Tissot". www.uci.org. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Steve (14 August 2025). "Richardson and Bjergfelt set world records". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 September 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Men Masters – best performance" (PDF). UCI.org. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Women Masters – best performance" (PDF). UCI.org. Retrieved 2022-09-12.

- ^ https://assets.usacycling.org/prod/documents/20241104_Men_Master_National-Records.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b CyclingTips (2015-02-16). "Putting the hour record into perspective: How does an amateur compare? – CyclingTips". cyclingtips.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Home" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-08. Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ^ a b c d "80-year-old Giuseppe Marinoni and three others broke hour records on Saturday in Milton – Canadian Cycling Magazine". 24 September 2017. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ "World Masters Track Cycling Championships 2019" (PDF). www.cyclingmasters.com.

- ^ a b c "Home" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ^ "Swinand (49) smashes Irish elite hour record in Colorado – Sticky Bottle – Sticky Bottle". www.stickybottle.com. 2016-11-22. Archived from the original on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ^ a b "Breaking the Hour: A New World Record – GU Energy Labs". 25 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ "Wow, New Masters 50-54 Hour World Record. – Bike Forums". www.bikeforums.net. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ a b "Masters Men 55-59 UCI Hour Record – Bike Forums". www.bikeforums.net. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ a b "World Masters Track Cycling Championships 2019" (PDF). www.cyclingmasters.com.

- ^ Media, Ben Delaney/Immediate (October 3, 2017). "Former Tour pro sets masters hour record". cyclingnews.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "Greg Swinand smashes Irish elite hour record in Mexico – Sticky Bottle". www.stickybottle.com. 2017-11-17. Archived from the original on 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ^ a b "Rob Gilmour Breaks UCI Hour Record For Veterans. – BritishCycleSport". britishcycle.wpengine.com. 2015-10-14. Archived from the original on 2021-11-24. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ^ Miu, Ryan. "The story behind a masters hour record". Cycling NSW. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020. not yet appearing on the UCI list.

- ^ Bertoncelj, Maja. "Andrej Žavbi do novega svetovnega rekorda". Gorenjski Glas. Retrieved 12 February 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Legendary Giuseppe Marinoni to Attempt 80-Year-Old Best Hour Record + Film". 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ "LCC member sets world record". lcc.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ^ a b "Shropshire cyclist, 81, sets age group UCI Hour record". 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "New cycling world record for Southland veteran Peter Grandiek at Velodrome". Stuff. 22 February 2015. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Walter breaks cycling world record – at 81!". Stourbridge News. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 2021-11-24. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ^ "Marinoni Narrowly Misses Best Hour Record Attempt at Packed Milton Velodrome + PHOTOS & Bell Lap VID". 20 August 2017. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ "85-year-old sets new age group Hour Record – Stourbridge Cycling Club". 22 September 2019. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ "90-year-old Frenchman rides more than 29km to set new age group Hour Record – Cycling Weekly". 23 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "Men masters best performances 2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- ^ "Reg is back on track – Avantidrome". 27 April 2019. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Robert Marchand sets new 100-kilometer speed record – VeloNews.com". 28 September 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Women Masters – Best performance" (PDF). UCI.ch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017.

- ^ a b "WestCycle". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 2021-11-24. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ "USA Cycling National Records – USA Cycling". www.usacycling.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ "Clarry's Hour – a UCI Masters hour record attempt". Archived from the original on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ a b c d "Women Masters – Best performance" (PDF). UCI.ch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2018.

- ^ "USA Cycling National Records". legacy.usacycling.org. USA Cycling. 2018-01-05. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ^ "Women masters best performances 2019" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ^ a b "Walton breaks Hour Record for juniors, sets new USA mark". 17 October 2022.

- ^ "National Records".

- ^ "Is Adelaide home to the junior Hour Record?: Aston Freeth's hour of power".

- ^ "British junior cyclist rides 49.1 km hour record". 14 March 2022.

- ^ "The History of the Recumbent Bicycle: Winning Forbidden". Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ Russo, Francesco (2016). "MetaStretto – The CURRENT World-Record-Speedbike!". www.russo-speedbike.com. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ UniSA (30 April 2019). "Speed records are broken". Australian HPV Super Series.

- ^ "World Recumbent Racing Association". recumbents.com.

- ^ "Le Breton Simon Jan bat un record du monde insolite sur des routes de campagne". actu.fr. October 12, 2021.

- ^ "Longest bicycle wheelie in one hour | Guinness World Records".

- ^ "Greatest distance on a penny farthing with one leg in one hour; Guinness World Records".

- ^ a b "WorldTour pro Davide Formolo sets record for shortest distance cycled in a hour". Cycling Magazine. 17 November 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ UCI Cycling Regulations. Part 3 Track Races. Version on 01.01.25. https://assets.ctfassets.net/761l7gh5x5an/6jGCKQEr7a5NTvzdo1mzzI/5837e48d94818fd35e0f31de19b146ce/3-PIS-01.01.2025_-_E_-_Regulations_update_2024__full__21022025.pdf

External links

[edit]Hour record

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Regulations

Overview of the Hour Record

The Hour Record is the greatest distance cycled in one hour from a standing start on a track bicycle.[1] Governed by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), the event requires riders to complete exactly 60 minutes of continuous effort on a velodrome without a flying start, emphasizing raw endurance and power output.[8] Regarded as the "Holy Grail" of cycling, the Hour Record holds immense prestige due to its solitary nature and extreme physical demands, testing a rider's aerobic capacity, threshold power, and mental resilience in isolation.[9] Unlike team-based or tactical events, it strips away external variables, focusing solely on individual performance against the clock. Basic equipment for the Hour Record consists of track bicycles compliant with UCI regulations for track endurance events, permitting aerodynamic features such as pursuit-style frames, clip-on handlebar extensions, disc wheels, and optimized components while ensuring safety and fairness.[1] The event is open to professional and amateur riders licensed under UCI governance, excluding tandem bicycles or those designed for non-track use, with attempts requiring prior approval from national federations and UCI technical verification.[10][8] Riders must also be enrolled in the UCI Registered Testing Pool and comply with anti-doping protocols, including the biological passport.[8] In distinction from other endurance events like road races, the Hour Record is a pure time trial conducted entirely on an indoor or outdoor velodrome, where riders maintain a consistent pace without drafting or competition from others.[1] This format highlights the event's purity as a benchmark of human cycling potential under controlled conditions.Evolution of UCI Rules

Before the formalization of rules by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) in 1972, hour record attempts were tracked informally by various cycling organizations and velodromes, with minimal oversight and no standardized equipment restrictions, permitting a wide range of bike positions and technologies that evolved alongside early bicycle innovations.[2] In 1972, the UCI introduced standardized regulations for the hour record, emphasizing traditional upright riding positions and limiting technological advancements to preserve the event's focus on human endurance, explicitly banning supine or extreme aerodynamic setups to align with conventional track cycling norms.[7] The 1990s saw significant controversies as riders experimented with non-traditional positions, such as Graeme Obree's "Old Faithful" tucked posture and later "Superman" prone extension, alongside Chris Boardman's use of aero bars and streamlined frames, sparking debates over fairness and tradition that pressured the UCI to intervene.[1] In 1997, the UCI responded by establishing two distinct categories—the official UCI Hour Record, which reverted to the 1972 Merckx-era specifications prohibiting extensions, aero bars, time trial helmets, and composite wheels to maintain historical integrity, and the Best Human Effort (or Athlete's Hour), which allowed more advanced equipment—effectively reclassifying post-1972 records into the latter to retroactively apply the stricter standards.[1][11] This bifurcation persisted until 2014, when the UCI unified the categories into a single modern framework, reversing prior restrictions to permit contemporary aerodynamic track pursuit bikes, positions, and components compliant with existing UCI track endurance event rules, with the goal of revitalizing interest and encouraging more attempts while eliminating the dual-class system.[12][13] Since 2014, the UCI has made only minor adjustments to the hour record regulations, primarily addressing safety protocols such as enhanced medical supervision and precise distance measurement via approved timing systems, with no substantive alterations to equipment or positional allowances in force as of November 2025, though updates including minimum handlebar widths and rim depth limits are scheduled for 2026-2027.[12][14]Historical Records

Pre-UCI Era (Before 1972)