Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

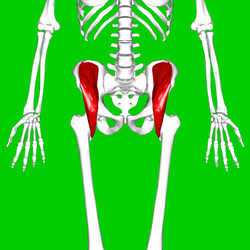

Iliacus muscle

View on Wikipedia| Iliacus muscle | |

|---|---|

Position of iliacus muscle (shown in red) | |

The iliacus and nearby muscles | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ɪˈlaɪ.əkəs/ |

| Origin | Upper two-thirds of the iliac fossa |

| Insertion | Base of the lesser trochanter of femur |

| Artery | Medial femoral circumflex artery, iliac branch of iliolumbar artery |

| Nerve | Femoral nerve |

| Actions | Flexes and rotates medially thigh[citation needed] |

| Antagonist | Gluteus maximus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus iliacus |

| TA98 | A04.7.02.003 |

| TA2 | 2594 |

| FMA | 22310 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The iliacus is a flat, triangular muscle which fills the iliac fossa. It forms the lateral portion of iliopsoas, providing flexion of the thigh and lower limb at the acetabulofemoral joint.

Structure

[edit]The iliacus arises from the iliac fossa on the interior side of the hip bone, and also from the region of the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS). It joins the psoas major to form the iliopsoas.[1] It proceeds across the iliopubic eminence through the muscular lacuna to its insertion on the lesser trochanter of the femur.[1] Its fibers are often inserted in front of those of the psoas major and extend distally over the lesser trochanter.[2]

Nerve supply

[edit]The iliopsoas is innervated by the femoral nerve and direct branches from the lumbar plexus.[3]

Function

[edit]In open-chain exercises, as part of the iliopsoas, the iliacus is important for lifting (flexing) the femur forward (e.g. front scale). In closed-chain exercises, the iliopsoas bends the trunk forward and can lift the trunk from a lying posture (e.g. sit-ups, back scale) because the psoas major crosses several vertebral joints and the sacroiliac joint. From its origin in the lesser pelvis the iliacus acts exclusively on the hip joint.[2]

Additional images

[edit]-

Position of iliacus muscle (shown in red). Animation.

-

Right hip bone. Internal surface. Iliac fossa visible at upper left.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Davenport, Kathleen L. (2019-01-01), Elson, Lauren E. (ed.), "Chapter 9 - The Professional Dancer's Hip", Performing Arts Medicine, Philadelphia: Elsevier, pp. 77–87, ISBN 978-0-323-58182-0, retrieved 2021-01-17

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p 234

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p 422

References

[edit]- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. 2006. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

External links

[edit]- PTCentral

- Anatomy figure: 40:07-05 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Muscles and nerves of the posterior abdominal wall."

- pelvis at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (femalepelvicdiaphragm, malepelvicdiaphragm)