Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mendelian inheritance

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

This article is missing information about a succinct statement of the theorem. (September 2024) |

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularized by William Bateson.[1] These principles were initially controversial. When Mendel's theories were integrated with the Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory of inheritance by Thomas Hunt Morgan in 1915, they became the core of classical genetics. Ronald Fisher combined these ideas with the theory of natural selection in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, putting evolution onto a mathematical footing and forming the basis for population genetics within the modern evolutionary synthesis.[2]

History

[edit]The principles of Mendelian inheritance were named for and first derived by Gregor Johann Mendel,[3] a nineteenth-century Moravian monk who formulated his ideas after conducting simple hybridization experiments with pea plants (Pisum sativum) he had planted in the garden of his monastery.[4] Between 1856 and 1863, Mendel cultivated and tested some 5,000 pea plants. From these experiments, he induced two generalizations which later became known as Mendel's Principles of Heredity or Mendelian inheritance. He described his experiments in a two-part paper, Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden (Experiments on Plant Hybridization),[5] that he presented to the Natural History Society of Brno on 8 February and 8 March 1865, and which was published in 1866.[3][6][7][8]

Mendel's results were at first largely ignored. Although they were not completely unknown to biologists of the time, they were not seen as generally applicable, even by Mendel himself, who thought they only applied to certain categories of species or traits. A major roadblock to understanding their significance was the importance attached by 19th-century biologists to the apparent blending of many inherited traits in the overall appearance of the progeny,[citation needed] now known to be due to multi-gene interactions, in contrast to the organ-specific binary characters studied by Mendel.[4] In 1900, however, his work was "re-discovered" by three European scientists, Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak. The exact nature of the "re-discovery" has been debated: De Vries published first on the subject, mentioning Mendel in a footnote, while Correns pointed out Mendel's priority after having read De Vries' paper and realizing that he himself did not have priority. De Vries may not have acknowledged truthfully how much of his knowledge of the laws came from his own work and how much came only after reading Mendel's paper. Later scholars have accused Von Tschermak of not truly understanding the results at all.[9][10]

Regardless, the "re-discovery" made Mendelism an important but controversial theory. Its most vigorous promoter in Europe was William Bateson, who coined the terms "genetics" and "allele" to describe many of its tenets.[11] The model of heredity was contested by other biologists because it implied that heredity was discontinuous, in opposition to the apparently continuous variation observable for many traits.[12] Many biologists also dismissed the theory because they were not sure it would apply to all species. However, later work by biologists and statisticians such as Ronald Fisher showed that if multiple Mendelian factors were involved in the expression of an individual trait, they could produce the diverse results observed, thus demonstrating that Mendelian genetics is compatible with natural selection.[13][14] Thomas Hunt Morgan and his assistants later integrated Mendel's theoretical model with the chromosome theory of inheritance, in which the chromosomes of cells were thought to hold the actual hereditary material, and created what is now known as classical genetics, a highly successful foundation which eventually cemented Mendel's place in history.[3][11]

Mendel's findings allowed scientists such as Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane to predict the expression of traits on the basis of mathematical probabilities. An important aspect of Mendel's success can be traced to his decision to start his crosses only with plants he demonstrated were true-breeding.[4][13] He only measured discrete (binary) characteristics, such as color, shape, and position of the seeds, rather than quantitatively variable characteristics. He expressed his results numerically and subjected them to statistical analysis. His method of data analysis and his large sample size gave credibility to his data. He had the foresight to follow several successive generations (P, F1, F2, F3) of pea plants and record their variations. Finally, he performed "test crosses" (backcrossing descendants of the initial hybridization to the initial true-breeding lines) to reveal the presence and proportions of recessive characters.[15]

Inheritance tools

[edit]Punnett squares

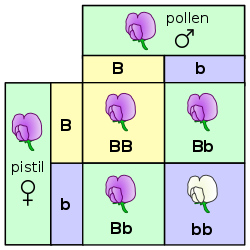

[edit]Punnett squares are a well known genetics tool that was created by an English geneticist, Reginald Punnett, which can visually demonstrate all the possible genotypes that an offspring can receive, given the genotypes of their parents.[16][17][18] Each parent carries two alleles, which can be shown on the top and the side of the chart, and each contribute one of them towards reproduction at a time. Each of the squares in the middle demonstrates the number of times each pairing of parental alleles could combine to make potential offspring. Using probabilities, one can then determine which genotypes the parents can create, and at what frequencies they can be created.[16][18]

For example, if two parents both have a heterozygous genotype, then there would be a 50% chance for their offspring to have the same genotype, and a 50% chance they would have a homozygous genotype. Since they could possibly contribute two identical alleles, the 50% would be halved to 25% to account for each type of homozygote, whether this was a homozygous dominant genotype, or a homozygous recessive genotype.[16][17][18]

Pedigrees

[edit]Pedigrees are visual tree like representations that demonstrate exactly how alleles are being passed from past generations to future ones.[19] They also provide a diagram displaying each individual that carries a desired allele, and exactly which side of inheritance it was received from, whether it was from their mother's side or their father's side.[19] Pedigrees can also be used to aid researchers in determining the inheritance pattern for the desired allele, because they share information such as the gender of all individuals, the phenotype, a predicted genotype, the potential sources for the alleles, and also based its history, how it could continue to spread in the future generations to come. By using pedigrees, scientists have been able to find ways to control the flow of alleles over time, so that alleles that act problematic can be resolved upon discovery.[20]

Mendel's genetic discoveries

[edit]Five parts of Mendel's discoveries were an important divergence from the common theories at the time and were the prerequisite for the establishment of his rules.

- Characters are unitary, that is, they are discrete e.g.: purple vs. white, tall vs. dwarf. There is no medium-sized plant or light purple flower.

- Genetic characteristics have alternate forms, each inherited from one of two parents. Today these are called alleles.

- One allele is dominant over the other. The phenotype reflects the dominant allele.

- Gametes are created by random segregation. Heterozygotic individuals produce gametes with an equal frequency of the two alleles.

- Different traits have independent assortment. In modern terms, genes are unlinked.

According to customary terminology, the principles of inheritance discovered by Gregor Mendel are here referred to as Mendelian laws, although today's geneticists also speak of Mendelian rules or Mendelian principles,[21][22] as there are many exceptions summarized under the collective term Non-Mendelian inheritance. The laws were initially formulated by the geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan in 1916.[23]

Mendel selected for the experiment the following characters of pea plants:

- Form of the ripe seeds (round or roundish, surface shallow or wrinkled)

- Colour of the seed–coat (white, gray, or brown, with or without violet spotting)

- Colour of the seeds and cotyledons (yellow or green)

- Flower colour (white or violet-red)

- Form of the ripe pods (simply inflated, not contracted, or constricted between the seeds and wrinkled)

- Colour of the unripe pods (yellow or green)

- Position of the flowers (axial or terminal)

- Length of the stem [26]

When he crossed purebred white flower and purple flower pea plants (the parental or P generation) by artificial pollination, the resulting flower colour was not a blend. Rather than being a mix of the two, the offspring in the first generation (F1-generation) were all purple-flowered. Therefore, he called this biological trait dominant. When he allowed self-fertilization in the uniform looking F1-generation, he obtained both colours in the F2 generation with a purple flower to white flower ratio of 3 : 1. In some of the other characters also one of the traits was dominant.

He then conceived the idea of heredity units, which he called hereditary "factors". Mendel found that there are alternative forms of factors—now called genes—that account for variations in inherited characteristics. For example, the gene for flower color in pea plants exists in two forms, one for purple and the other for white. The alternative "forms" are now called alleles. For each trait, an organism inherits two alleles, one from each parent. These alleles may be the same or different. An organism that has two identical alleles for a gene is said to be homozygous for that gene (and is called a homozygote). An organism that has two different alleles for a gene is said to be heterozygous for that gene (and is called a heterozygote).

Mendel hypothesized that allele pairs separate randomly, or segregate, from each other during the production of the gametes in the seed plant (egg cell) and the pollen plant (sperm). Because allele pairs separate during gamete production, a sperm or egg carries only one allele for each inherited trait. When sperm and egg unite at fertilization, each contributes its allele, restoring the paired condition in the offspring. Mendel also found that each pair of alleles segregates independently of the other pairs of alleles during gamete formation.

The genotype of an individual is made up of the many alleles it possesses. The phenotype is the result of the expression of all characteristics that are genetically determined by its alleles as well as by its environment. The presence of an allele does not mean that the trait will be expressed in the individual that possesses it. If the two alleles of an inherited pair differ (the heterozygous condition), then one determines the organism's appearance and is called the dominant allele; the other has no noticeable effect on the organism's appearance and is called the recessive allele.

Mendel's laws of inheritance

[edit]| Law | Definition |

|---|---|

| Law of dominance and uniformity | Some alleles are dominant while others are recessive; an organism with at least one dominant allele will display the effect of the dominant allele.[27] |

| Law of segregation | During gamete formation, the alleles for each gene segregate from each other so that each gamete carries only one allele for each gene. |

| Law of independent assortment | Genes of different traits can segregate independently during the formation of gametes. |

Law of dominance and uniformity

[edit]

F2 generation: The phenotypes in the second generation show a 3 : 1 ratio.

In the genotype 25 % are homozygous with the dominant trait, 50 % are heterozygous genetic carriers of the recessive trait, 25 % are homozygous with the recessive genetic trait and expressing the recessive character.

If two parents are mated with each other who differ in one genetic characteristic for which they are both homozygous (each pure-bred), all offspring in the first generation (F1) are equal to the examined characteristic in genotype and phenotype showing the dominant trait. This uniformity rule or reciprocity rule applies to all individuals of the F1-generation.[30]

The principle of dominant inheritance discovered by Mendel states that in a heterozygote the dominant allele will cause the recessive allele to be "masked": that is, not expressed in the phenotype. Only if an individual is homozygous with respect to the recessive allele will the recessive trait be expressed. Therefore, a cross between a homozygous dominant and a homozygous recessive organism yields a heterozygous organism whose phenotype displays only the dominant trait.

The F1 offspring of Mendel's pea crosses always looked like one of the two parental varieties. In this situation of "complete dominance", the dominant allele had the same phenotypic effect whether present in one or two copies.

But for some characteristics, the F1 hybrids have an appearance in between the phenotypes of the two parental varieties. A cross between two four o'clock (Mirabilis jalapa) plants shows an exception to Mendel's principle, called incomplete dominance. Flowers of heterozygous plants have a phenotype somewhere between the two homozygous genotypes. In cases of intermediate inheritance (incomplete dominance) in the F1-generation Mendel's principle of uniformity in genotype and phenotype applies as well. Research about intermediate inheritance was done by other scientists. The first was Carl Correns with his studies about Mirabilis jalapa.[28][31][32][33][34]

Law of segregation of genes

[edit]

The law of segregation of genes applies when two individuals, both heterozygous for a certain trait are crossed, for example, hybrids of the F1-generation. The offspring in the F2-generation differ in genotype and phenotype so that the characteristics of the grandparents (P-generation) regularly occur again. In a dominant-recessive inheritance, an average of 25% are homozygous with the dominant trait, 50% are heterozygous showing the dominant trait in the phenotype (genetic carriers), 25% are homozygous with the recessive trait and therefore express the recessive trait in the phenotype. The genotypic ratio is 1: 2 : 1, and the phenotypic ratio is 3: 1.

In the pea plant example, the capital "B" represents the dominant allele for purple blossom and lowercase "b" represents the recessive allele for white blossom. The pistil plant and the pollen plant are both F1-hybrids with genotype "B b". Each has one allele for purple and one allele for white. In the offspring, in the F2-plants in the Punnett-square, three combinations are possible. The genotypic ratio is 1 BB : 2 Bb : 1 bb. But the phenotypic ratio of plants with purple blossoms to those with white blossoms is 3 : 1 due to the dominance of the allele for purple. Plants with homozygous "b b" are white flowered like one of the grandparents in the P-generation.

In cases of incomplete dominance the same segregation of alleles takes place in the F2-generation, but here also the phenotypes show a ratio of 1 : 2 : 1, as the heterozygous are different in phenotype from the homozygous because the genetic expression of one allele compensates the missing expression of the other allele only partially. This results in an intermediate inheritance which was later described by other scientists.

In some literature sources, the principle of segregation is cited as the "first law". Nevertheless, Mendel did his crossing experiments with heterozygous plants after obtaining these hybrids by crossing two purebred plants, discovering the principle of dominance and uniformity first.[35][27]

Molecular proof of segregation of genes was subsequently found through observation of meiosis by two scientists independently, the German botanist Oscar Hertwig in 1876, and the Belgian zoologist Edouard Van Beneden in 1883. Most alleles are located in chromosomes in the cell nucleus. Paternal and maternal chromosomes get separated in meiosis because during spermatogenesis the chromosomes are segregated on the four sperm cells that arise from one mother sperm cell, and during oogenesis the chromosomes are distributed between the polar bodies and the egg cell. Every individual organism contains two alleles for each trait. They segregate (separate) during meiosis such that each gamete contains only one of the alleles.[36] When the gametes unite in the zygote the alleles—one from the mother one from the father—get passed on to the offspring. An offspring thus receives a pair of alleles for a trait by inheriting homologous chromosomes from the parent organisms: one allele for each trait from each parent.[36] Heterozygous individuals with the dominant trait in the phenotype are genetic carriers of the recessive trait.

Law of independent assortment

[edit]

Now two heterozygous mature individuals of such F1-generation are bred together. The dominant allele "E" (on the extension locus) provides black eumelanin in the coat. The recessive allele "e" (on the extension locus) hinders the storage of eumelanin in the coat, so only the pigments for the "Tan" colour are in the coat. The dominant allele S (on the S-locus) provides for the pigmentation of the entire coat. The recessive allele sP (on the S-locus) causes a white Piebald spotting.[37] Now in the puppies in the F2-generation all combinations are possible. The Piebald spotting and the genes for the different colour pigments are inherited independently of each other.[38] Average number ratio of phenotypes 9:3:3:1.[39]

The law of independent assortment proposes alleles for separate traits are passed independently of one another.[40][35] That is, the biological selection of an allele for one trait has nothing to do with the selection of an allele for any other trait. Mendel found support for this law in his dihybrid cross experiments. In his monohybrid crosses, an idealized 3:1 ratio between dominant and recessive phenotypes resulted. In dihybrid crosses, however, he found a 9:3:3:1 ratios. This shows that each of the two alleles is inherited independently from the other, with a 3:1 phenotypic ratio for each.

Independent assortment occurs in eukaryotic organisms during meiotic metaphase I, and produces a gamete with a mixture of the organism's chromosomes. The physical basis of the independent assortment of chromosomes is the random orientation of each bivalent chromosome along the metaphase plate with respect to the other bivalent chromosomes. Along with crossing over, independent assortment increases genetic diversity by producing novel genetic combinations.

There are many deviations from the principle of independent assortment due to genetic linkage.

Of the 46 chromosomes in a normal diploid human cell, half are maternally derived (from the mother's egg) and half are paternally derived (from the father's sperm). This occurs as sexual reproduction involves the fusion of two haploid gametes (the egg and sperm) to produce a zygote and a new organism, in which every cell has two sets of chromosomes (diploid). During gametogenesis the normal complement of 46 chromosomes needs to be halved to 23 to ensure that the resulting haploid gamete can join with another haploid gamete to produce a diploid organism.

In independent assortment, the chromosomes that result are randomly sorted from all possible maternal and paternal chromosomes. Because zygotes end up with a mix instead of a pre-defined "set" from either parent, chromosomes are therefore considered assorted independently. As such, the zygote can end up with any combination of paternal or maternal chromosomes. For human gametes, with 23 chromosomes, the number of possibilities is 223 or 8,388,608 possible combinations.[41] This contributes to the genetic variability of progeny. Generally, the recombination of genes has important implications for many evolutionary processes.[42][43][44]

Mendelian trait

[edit]A Mendelian trait is one whose inheritance follows Mendel's principles—namely, the trait depends only on a single locus, whose alleles are either dominant or recessive.

Many traits are inherited in a non-Mendelian fashion.[45]

Non-Mendelian inheritance

[edit]Mendel himself warned that care was needed in extrapolating his patterns to other organisms or traits. Indeed, many organisms have traits whose inheritance works differently from the principles he described; these traits are called non-Mendelian.[46][47]

For example, Mendel focused on traits whose genes have only two alleles, such as "A" and "a". However, many genes have more than two alleles. He also focused on traits determined by a single gene. But some traits, such as height, depend on many genes rather than just one. Traits dependent on multiple genes are called polygenic traits.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ William Bateson: Mendel's Principles of Heredity - A Defence, with a Translation of Mendel's Original Papers on Hybridisation Cambridge University Press 2009, ISBN 978-1-108-00613-2

- ^ Grafen, Alan; Ridley, Mark (2006). Richard Dawkins: How A Scientist Changed the Way We Think. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-19-929116-8.

- ^ a b c Fairbanks, Daniel J.; Rytting, Bryce (May 2001). "Mendelian controversies: a botanical and historical review". American Journal of Botany. 88 (5): 737–752. doi:10.2307/2657027. ISSN 0002-9122. JSTOR 2657027. PMID 11353700.

- ^ a b c Henig, Robin Marantz (2000). The monk in the garden : the lost and found genius of Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics. Internet Archive. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-97765-1.

- ^ Mendel, Gregor; Mendel, Gregor (1866). Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden. Brünn: Im Verlage des Vereines.

- ^ "Mendel's Paper (English - Annotated)". www.mendelweb.org. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Mendel, Gregor (1970), Mendel, Gregor (ed.), Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden, Ostwalds Klassiker der Exakten Wissenschaften (in German), Wiesbaden: Vieweg+Teubner Verlag, pp. 21–64, doi:10.1007/978-3-663-19714-0_4, ISBN 978-3-663-19714-0, retrieved 23 March 2024

- ^ Mielewczik, Michael; Moll-Mielewczik, Janine; Simunek, Michal V.; Hossfeld, Uwe (1 September 2022). ""Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden" — neue Einsichten". BIOspektrum (in German). 28 (5): 565. doi:10.1007/s12268-022-1820-8. ISSN 1868-6249.

- ^ Monaghan, Floyd V.; Corcos, Alain F. (1987). "Tschermak: A non-discoverer of Mendelism II. A critique". Journal of Heredity. 78 (3): 208–210. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a110361. PMID 3302014.

- ^ Simunek, Michal V. (January 2011). The Mendelian Dioskuri. Correspondence of Armin with Erich von Tschermak-Seysenegg, 1898-1951. Pavel Mervart & Institute of Contemporary History of the AcSc Prague. ISBN 978-80-87378-67-0.

- ^ a b Goldschmidt, Richard B. (1 January 1951). "Chromosomes and Genes". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 16: 1–11. doi:10.1101/SQB.1951.016.01.003. ISSN 0091-7451. PMID 14942726.

- ^ Sumner, Francis B. (1929). "Is Evolution a Continuous or Discontinuous Process?". The Scientific Monthly. 29 (1): 72–78. ISSN 0096-3771. JSTOR 14824.

- ^ a b Fisher, Sir Ronald Aylmer (21 October 1999). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection: A Complete Variorum Edition. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-850440-5.

- ^ Fisher, R. A. (1919). "XV.—The Correlation between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 52 (2): 399–433. doi:10.1017/S0080456800012163. S2CID 181213898.

- ^ "Gregor Mendel and the Principles of Inheritance | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Basic Principles of Genetics: Probability of Inheritance". www.palomar.edu. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ a b Churchill, Frederick B. (1974). "William Johannsen and the Genotype Concept". Journal of the History of Biology. 7 (1): 5–30. doi:10.1007/BF00179291. ISSN 0022-5010. JSTOR 4330602. PMID 11610096.

- ^ a b c Edwards, A. W. F. (1 March 2012). "Punnett's square". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. Data-Driven Research in the Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 43 (1): 219–224. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2011.11.011. ISSN 1369-8486. PMID 22326091.

- ^ a b Miller, Christine (2020). "5.13 Mendelian Inheritance". Human biology. Thompson Rivers University.

- ^ Galla, Stephanie J.; Brown, Liz; Couch-Lewis (Ngāi Tahu: Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke, Ngāti Waewae), Yvette; Cubrinovska, Ilina; Eason, Daryl; Gooley, Rebecca M.; Hamilton, Jill A.; Heath, Julie A.; Hauser, Samantha S. (January 2022). "The relevance of pedigrees in the conservation genomics era". Molecular Ecology. 31 (1): 41–54. Bibcode:2022MolEc..31...41G. doi:10.1111/mec.16192. PMC 9298073. PMID 34553796.

- ^ Science Learning Hub: Mendel's principles of inheritance

- ^ Noel Clarke: Mendelian Genetics - An overview

- ^ Marks, Jonarhan (22 December 2008). "The Construction of Mendel's Laws". Evolutionary Anthropology. 17 (6): 250–253. doi:10.1002/evan.20192.

- ^ Gregor Mendel: Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden Verhandlungen des Naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn. Bd. IV. 1866, page 8

- ^ Write Work: Mendel's Impact

- ^ Gregor Mendel: Experiments in Plant Hybridization 1965, page 5

- ^ a b Rutgers: Mendelian Principles Archived 14 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Biology University of Hamburg: Mendelian Genetics

- ^ Neil A. Campbell, Jane B. Reece: Biologie. Spektrum-Verlag Heidelberg-Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-8274-1352-4, page 302–303.

- ^ Ulrich Weber: Biologie Gesamtband Oberstufe, 1st edition, Cornelsen Verlag Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-464-04279-0, page 170 - 171.

- ^ Biologie Schule - kompaktes Wissen: Uniformitätsregel (1. Mendelsche Regel)

- ^ Frustfrei Lernen: Uniformitätsregel (1. Mendelsche Regel)

- ^ Spektrum Biologie: Unvollständige Dominanz

- ^ Spektrum Biologie: Intermediärer Erbgang

- ^ a b Neil A. Campbell, Jane B. Reece: Biologie. Spektrum-Verlag 2003, page 293–315. ISBN 3-8274-1352-4

- ^ a b Bailey, Regina (5 November 2015). "Mendel's Law of Segregation". about education. About.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Genomia.cz: Yorkshire Terrier.

- ^ Anna Laukner: Die Genetik der Fellfarben beim Hund. Kynos 2021, ISBN 978-3954642618.

- ^ Spectrum Dictionary of Biology: Mendelian Rules

- ^ Bailey, Regina. "Independent Assortment". Thoughtco. About.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Perez, Nancy. "Meiosis". Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ Stapley, J.; Feulner, P. G.; Johnston, S. E.; Santure, A. W.; Smadja, C. M. (2017). "Recombination: The good, the bad and the variable". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 372 (1736). doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0279. PMC 5698631. PMID 29109232.

- ^ Reeve, James; Ortiz-Barrientos, Daniel; Engelstädter, Jan (2016). "The evolution of recombination rates in finite populations during ecological speciation". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 283 (1841). doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1243. PMC 5095376. PMID 27798297.

- ^ Hickey, Donal A.; Golding, G. Brian (2018). "The advantage of recombination when selection is acting at many genetic Loci". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 442: 123–128. Bibcode:2018JThBi.442..123H. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.01.018. PMID 29355539.

- ^ "Genetic Disorders". National Human Genome Research Institute. 18 May 2018.

- ^ Schacherer, Joseph (2016). "Beyond the simplicity of Mendelian inheritance". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 339 (7–8): 284–288. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2016.04.006. PMID 27344551.

- ^ Khan Academy: Variations on Mendel's laws (overview)

Further reading

[edit]- Bowler, Peter J. (1989). The Mendelian Revolution: The Emergence of Hereditarian Concepts in Modern Science and Society. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Atics, Jean. Genetics: The life of DNA. ANDRNA press.

- Reece, Jane B.; Campbell, Neil A. (2011). Mendel and the Gene Idea (9th ed.). Benjamin Cummings / Pearson Education. p. 265.

External links

[edit]- Khan Academy, video lecture

- Probability of Inheritance Archived 4 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Mendel's principles of Inheritance

- Mendelian genetics Archived 10 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine

Mendelian inheritance

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Gregor Mendel and His Experiments

Gregor Johann Mendel was born on July 20, 1822, in Heinzendorf bei Odrau, a small village in Austrian Silesia (now Hynčice, Czech Republic), to a family of ethnic Germans who worked as farmers.[8] Despite financial hardships, he excelled in school and pursued higher education, studying philosophy, physics, and natural history at the University of Olmütz from 1840 to 1843 before financial difficulties forced him to pause.[8] In 1843, Mendel joined the Augustinian order at the St. Thomas's Abbey in Brno (then Brünn), adopting the name Gregor and continuing his studies in theology and science, including a period at the University of Vienna from 1850 to 1852 where he focused on natural sciences under physicists like Christian Doppler.[9] He returned to Brno as a substitute teacher and later conducted his research at the abbey, which supported scientific inquiry, eventually becoming its abbot in 1868.[8] Between 1856 and 1863, Mendel conducted systematic experiments on inheritance using garden pea plants (Pisum sativum) in the abbey garden, choosing them for their ease of cultivation, short generation time, and ability to self-pollinate or be cross-pollinated under controlled conditions.[2] He focused on seven distinct traits, each with two contrasting forms: seed shape (round or wrinkled), seed color (yellow or green), flower color (purple or white), pod shape (inflated or constricted), pod color (green or yellow), plant height (tall or dwarf), and flower position (axial or terminal).[10] To ensure pure lines, Mendel first grew plants that consistently produced offspring identical to themselves through self-pollination, then performed controlled crosses by manually transferring pollen between plants while preventing self-pollination.[2] Mendel's approach emphasized quantitative analysis; he planted and tracked thousands of pea plants—examining nearly 30,000 individuals across generations—to record precise counts of traits in offspring.[11] In monohybrid crosses, involving one trait such as seed shape, he crossed pure round-seeded plants with pure wrinkled-seeded ones; the first filial (F1) generation uniformly showed round seeds, but the second (F2) generation exhibited a 3:1 ratio of round to wrinkled seeds, with 5,474 round and 1,850 wrinkled among 7,324 F2 seeds examined.[10][11] For dihybrid crosses, examining two traits like seed shape and color, the F2 generation revealed a 9:3:3:1 phenotypic ratio among 556 seeds, with 315 round yellow, 101 wrinkled yellow, 108 round green, and 32 wrinkled green.[12] These consistent ratios, derived from large sample sizes, allowed Mendel to infer underlying patterns of inheritance rather than relying on qualitative observations.[13] In 1865, Mendel presented his findings to the Natural History Society of Brünn, and in 1866, he published them in the society's proceedings under the title Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden (Experiments on Plant Hybrids), a 44-page paper detailing his methods, data, and mathematical interpretations.[2] The work received little attention during his lifetime, partly due to its publication in a local journal and the era's focus on Darwinian evolution over discrete inheritance mechanisms.[9] From these experiments, Mendel derived three fundamental principles of heredity that form the basis of Mendelian inheritance.[2]Rediscovery and Impact

Mendel's 1866 paper on plant hybridization, published in the Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn, received little attention due to the journal's limited circulation—only about 115 copies were printed, with few distributed beyond local circles—and because his mathematical approach to inheritance contrasted sharply with the dominant blending inheritance theory, which emphasized qualitative descriptions over quantitative ratios.[14] Prominent scientists like Carl Nägeli, to whom Mendel sent copies, dismissed the work without fully engaging its implications, further contributing to its obscurity for over three decades.[15] The rediscovery occurred in 1900 when three botanists—Hugo de Vries in the Netherlands, Carl Correns in Germany, and Erich von Tschermak in Austria—independently conducted experiments on plant traits, particularly peas, and arrived at results mirroring Mendel's ratios.[5] De Vries referenced Mendel in his book Die Mutationstheorie, while Correns and von Tschermak cited the original paper in their respective publications, sparking widespread interest and prompting translations of Mendel's work into major languages.[16] This revival profoundly shaped early 20th-century biology, establishing Mendelian principles as the cornerstone of the emerging field of genetics. In 1909, Danish botanist Wilhelm Johannsen introduced the term "gene" (Gen) to denote the fundamental units of heredity in his book Elemente der exakten Erblichkeitslehre, building directly on Mendel's concepts of discrete factors.[17] American geneticist Thomas Hunt Morgan further validated Mendel's laws through his 1910 experiments with Drosophila melanogaster fruit flies, where he observed sex-linked inheritance of eye color traits, providing empirical support for the chromosomal theory of inheritance and demonstrating gene linkage on chromosomes.[18] By the 1930s and 1940s, Mendelian genetics formed the genetic foundation for the modern evolutionary synthesis, which reconciled Darwin's natural selection with particulate inheritance through key works by Ronald Fisher, J.B.S. Haldane, Sewall Wright, Theodosius Dobzhansky, and Julian Huxley, resolving earlier conflicts between Mendelism and evolution.[19] This integration elevated genetics to a central discipline in biology, influencing fields from agriculture to medicine and enabling quantitative predictions of trait transmission across generations.[20]Core Principles

Law of Segregation

The law of segregation, one of the foundational principles of Mendelian inheritance, states that during the formation of gametes, the two alleles for each gene in a diploid organism separate from each other, such that each gamete receives only one allele.[21] This ensures that offspring inherit one allele from each parent, maintaining genetic variation across generations.[22] Gregor Mendel derived this principle from his experiments with pea plants in the mid-1860s, where he observed consistent patterns in monohybrid crosses involving a single trait, such as seed color.[23] In a typical cross between pure-breeding parents with contrasting traits (e.g., yellow-seeded AA crossed with green-seeded aa), the first filial generation (F1) uniformly exhibited the dominant trait (all Aa, yellow seeds), indicating that the alleles did not blend but remained distinct. Self-pollinating the F1 heterozygotes to produce the second filial generation (F2) yielded a 3:1 phenotypic ratio of dominant to recessive traits (three yellow-seeded to one green-seeded), with genotypic proportions of 1 AA : 2 Aa : 1 aa. This 3:1 ratio provided evidence for segregation, as it demonstrated the reappearance of recessive traits in a predictable proportion, disproving the prevailing theory of blending inheritance where traits would permanently mix and dilute across generations.[21][24] An analogous example can be seen in dog coat length, where short hair is dominant to long hair, following a simple Mendelian pattern. Crossing a short-haired dog homozygous for the dominant allele with a long-haired dog (homozygous recessive) produces all short-haired offspring in the F1 generation. Interbreeding these F1 heterozygotes results in an F2 generation with a 3:1 ratio of short-haired to long-haired dogs, illustrating the segregation of alleles and the reappearance of the recessive trait.[25] Mathematically, the law predicts the probabilities of offspring genotypes in an F2 generation from a heterozygous cross (Aa × Aa). Each parent contributes gametes with equal probability: 50% A and 50% a. The resulting genotypic ratios are AA, Aa, and aa, which combine to produce the observed 3:1 phenotypic ratio under complete dominance.[22] At the cellular level, the law of segregation is mechanistically explained by the process of meiosis, where homologous chromosomes—and the alleles they carry—separate during anaphase I of meiosis I.[26] This separation ensures a 1:1 ratio of allele distribution in gametes from a heterozygote (e.g., 50% carrying A and 50% carrying a), as each gamete receives a single copy of the chromosome from the pair.[26] Although Mendel formulated the law without knowledge of chromosomes or meiosis, later cytological observations in the early 20th century confirmed this underlying mechanism.[26]Law of Independent Assortment

The law of independent assortment states that the alleles of two or more different genes get sorted into gametes independently of one another during gamete formation, meaning the inheritance of one trait does not affect the inheritance of another.[26] This principle applies when the genes are located on different chromosomes or are sufficiently far apart on the same chromosome to behave as if unlinked.[27] The mechanism underlying this law occurs during metaphase I of meiosis, where homologous chromosome pairs align randomly at the metaphase plate, leading to independent segregation of different gene pairs into daughter cells.[26] As a result, each gamete receives a random combination of alleles from the parent, producing genetic variation in offspring.[27] Gregor Mendel formulated this law based on his observations, though he did not know the chromosomal basis at the time.[28] Evidence for the law came from Mendel's dihybrid crosses, such as those involving seed color (yellow dominant to green) and seed shape (round dominant to wrinkled) in pea plants.[28] In the F2 generation of a cross between plants heterozygous for both traits (YyRr × YyRr), Mendel observed a phenotypic ratio of 9 round-yellow : 3 round-green : 3 wrinkled-yellow : 1 wrinkled-green, indicating that the traits assorted independently.[28] This ratio arose because each dihybrid parent produces four types of gametes (YR, Yr, yR, yr) in equal proportions of 1/4 each.[26] Mathematically, the independent assortment leads to 16 possible zygote combinations from the random union of these gametes, yielding the 9:3:3:1 phenotypic ratio under complete dominance.[28] For instance, the probability of a round-yellow zygote (dominant for both) is (3/4) × (3/4) = 9/16, while double recessive is (1/4) × (1/4) = 1/16.[26] This law held for the pairs of traits Mendel studied in dihybrid crosses, as those genes were located on different chromosomes or sufficiently far apart on the same chromosome to assort independently, though Mendel assumed no linkage and did not explain deviations that might occur in other cases.[28][29] His selection of unlinked traits allowed the independent assortment to be observed clearly, though the law assumes genes assort freely without physical connections.[30]Law of Dominance

The Law of Dominance, a foundational principle in Mendelian inheritance, posits that in heterozygous organisms, one allele—the dominant allele—fully expresses its associated phenotype, such as tall height masking the recessive short height, completely masking the effect of the other allele, known as the recessive allele. This results in the heterozygote displaying the same observable trait as the homozygous dominant individual. Gregor Mendel formulated this principle based on his systematic experiments with pea plants, where he observed consistent patterns of trait expression across generations.[31] In Mendel's experiments, he selected seven contrasting traits in pea plants (Pisum sativum), each controlled by a single factor (now understood as a gene), and crossed true-breeding parental lines differing in one trait at a time. For instance, crossing plants homozygous for round seeds (RR) with those homozygous for wrinkled seeds (rr) produced an F1 generation where all offspring exhibited round seeds, demonstrating that the round allele dominated over the wrinkled allele. Mendel noted that "the hybrid seed is always round, like that of the round parent," with no intermediate or blended forms appearing in the F1 hybrids. This uniformity in the F1 generation across all seven traits—such as tall stem height dominating over short, yellow seed color over green, and smooth pod texture over constricted—illustrated the masking effect of the dominant allele at the phenotypic level, even though both alleles were present genotypically.[28][2] Upon self-fertilizing the F1 hybrids to produce the F2 generation, Mendel observed the reappearance of the recessive trait, with approximately three-quarters of the offspring showing the dominant phenotype and one-quarter displaying the recessive one, yielding a 3:1 phenotypic ratio. In the seed shape example, out of 7,324 F2 seeds examined, 5,474 were round and 1,850 were wrinkled, closely approximating the 3:1 ratio (2.96:1 observed). This ratio emerged consistently for each trait studied, confirming that the recessive allele, though hidden in heterozygotes, persists and segregates into gametes for transmission to future generations. The Law of Dominance thus explains the phenotypic uniformity in F1 hybrids while accounting for the genetic potential for variation in subsequent generations.[31][28] While Mendel's pea experiments exemplified complete dominance, where the dominant phenotype entirely supplants the recessive, he acknowledged in his work that some plant hybrids exhibit incomplete dominance, resulting in intermediate phenotypes rather than full masking. However, such cases deviate from the strict Mendelian model observed in his selected traits and are not central to the Law of Dominance as originally described.[1]Analytical Tools

Punnett Squares

Punnett squares serve as a diagrammatic representation for predicting the probable genotypes and phenotypes of offspring resulting from specific genetic crosses, based on the principles of Mendelian inheritance.[32] This tool facilitates the visualization of how parental alleles segregate and combine in gametes during reproduction.[33] The method was invented by British geneticist Reginald C. Punnett in 1905, appearing prominently in his work and related correspondence as a simple grid to illustrate gamete combinations, too late for the initial edition of his book Mendelism but integral to subsequent genetic analyses.[34] Punnett developed it amid the early 20th-century revival of Mendel's ideas, providing a practical means to apply concepts like segregation without complex calculations.[35] For a monohybrid cross involving a single trait, such as the inheritance of seed color where A represents the dominant allele for yellow and a the recessive for green, a 2x2 Punnett square is constructed. Consider parents both heterozygous (Aa). The possible gametes from each parent are A and a, listed along the top and side of the grid. Filling the squares yields the offspring genotypes: AA, Aa, Aa, and aa, resulting in a genotypic ratio of 1:2:1 and a phenotypic ratio of 3:1 (yellow to green).[36]| A | a | |

|---|---|---|

| A | AA | Aa |

| a | Aa | aa |