Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

DNA sequencing

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. The advent of rapid DNA sequencing methods has greatly accelerated biological and medical research and discovery.[1][2]

Knowledge of DNA sequences has become indispensable for basic biological research, DNA Genographic Projects and in numerous applied fields such as medical diagnosis, biotechnology, forensic biology, virology and biological systematics. Comparing healthy and mutated DNA sequences can diagnose different diseases including various cancers,[3] characterize antibody repertoire,[4] and can be used to guide patient treatment.[5] Having a quick way to sequence DNA allows for faster and more individualized medical care to be administered, and for more organisms to be identified and cataloged.[4]

The rapid advancements in DNA sequencing technology have played a crucial role in sequencing complete genomes of humans, as well as numerous animal, plant, and microbial species.

The first DNA sequences were obtained in the early 1970s by academic researchers using laborious methods based on two-dimensional chromatography. Following the development of fluorescence-based sequencing methods with a DNA sequencer,[6] DNA sequencing has become easier and orders of magnitude faster.[7][8]

Applications

[edit]DNA sequencing can be used to determine the sequence of individual genes, larger genetic regions (i.e. clusters of genes or operons), full chromosomes, or entire genomes of any organism. DNA sequencing is also the most efficient way to indirectly sequence RNA or proteins (via their open reading frames). In fact, DNA sequencing has become a key technology in many areas of biology and other sciences such as medicine, forensics, and anthropology. [citation needed]

Molecular biology

[edit]Sequencing is used in molecular biology to study genomes and the proteins they encode. Information obtained using sequencing allows researchers to identify changes in genes and noncoding DNA (including regulatory sequences), associations with diseases and phenotypes, and identify potential drug targets. [citation needed]

Evolutionary biology

[edit]Since DNA is an informative macromolecule in terms of transmission from one generation to another, DNA sequencing is used in evolutionary biology to study how different organisms are related and how they evolved. In February 2021, scientists reported, for the first time, the sequencing of DNA from animal remains, a mammoth in this instance, over a million years old, the oldest DNA sequenced to date.[9][10]

Metagenomics

[edit]The field of metagenomics involves identification of organisms present in a body of water, sewage, dirt, debris filtered from the air, or swab samples from organisms. Knowing which organisms are present in a particular environment is critical to research in ecology, epidemiology, microbiology, and other fields. Sequencing enables researchers to determine which types of microbes may be present in a microbiome, for example. [citation needed]

Virology

[edit]As most viruses are too small to be seen by a light microscope, sequencing is one of the main tools in virology to identify and study the virus.[11] Viral genomes can be based in DNA or RNA. RNA viruses are more time-sensitive for genome sequencing, as they degrade faster in clinical samples.[12] Traditional Sanger sequencing and next-generation sequencing are used to sequence viruses in basic and clinical research, as well as for the diagnosis of emerging viral infections, molecular epidemiology of viral pathogens, and drug-resistance testing. There are more than 2.3 million unique viral sequences in GenBank.[11] In 2019, NGS has surpassed traditional Sanger as the most popular approach for generating viral genomes.[11]

During the 1997 avian influenza outbreak, viral sequencing determined that the influenza sub-type originated through reassortment between quail and poultry. This led to legislation in Hong Kong that prohibited selling live quail and poultry together at market. Viral sequencing can also be used to estimate when a viral outbreak began by using a molecular clock technique.[12]

Medicine

[edit]Medical technicians may sequence genes (or, theoretically, full genomes) from patients to determine if there is risk of genetic diseases. This is a form of genetic testing, though some genetic tests may not involve DNA sequencing. [citation needed]

As of 2013 DNA sequencing was increasingly used to diagnose and treat rare diseases. As more and more genes are identified that cause rare genetic diseases, molecular diagnoses for patients become more mainstream. DNA sequencing allows clinicians to identify genetic diseases, improve disease management, provide reproductive counseling, and more effective therapies.[13] Gene sequencing panels are used to identify multiple potential genetic causes of a suspected disorder.[14]

Also, DNA sequencing may be useful for determining a specific bacteria, to allow for more precise antibiotics treatments, hereby reducing the risk of creating antimicrobial resistance in bacteria populations.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

Forensic investigation

[edit]DNA sequencing may be used along with DNA profiling methods for forensic identification[21] and paternity testing. DNA testing has evolved tremendously in the last few decades to ultimately link a DNA print to what is under investigation. The DNA patterns in fingerprint, saliva, hair follicles, etc. uniquely separate each living organism from another. Testing DNA is a technique which can detect specific genomes in a DNA strand to produce a unique and individualized pattern. [citation needed]

The four canonical bases

[edit]The canonical structure of DNA has four bases: thymine (T), adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). DNA sequencing is the determination of the physical order of these bases in a molecule of DNA. However, there are many other bases that may be present in a molecule. In some viruses (specifically, bacteriophage), cytosine may be replaced by hydroxy methyl or hydroxy methyl glucose cytosine.[22] In mammalian DNA, variant bases with methyl groups or phosphosulfate may be found.[23][24] Depending on the sequencing technique, a particular modification, e.g., the 5mC (5-Methylcytosine) common in humans, may or may not be detected.[25]

In almost all organisms, DNA is synthesized in vivo using only the 4 canonical bases; modification that occurs post replication creates other bases like 5 methyl C. However, some bacteriophage can incorporate a non standard base directly.[26]

In addition to modifications, DNA is under constant assault by environmental agents such as UV and Oxygen radicals. At the present time, the presence of such damaged bases is not detected by most DNA sequencing methods, although PacBio has published on this.[27]

History

[edit]Discovery of DNA structure and function

[edit]Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was first discovered and isolated by Friedrich Miescher in 1869, but it remained under-studied for many decades because proteins, rather than DNA, were thought to hold the genetic blueprint to life. This situation changed after 1944 as a result of some experiments by Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty demonstrating that purified DNA could change one strain of bacteria into another. This was the first time that DNA was shown capable of transforming the properties of cells. [citation needed]

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick put forward their double-helix model of DNA, based on crystallized X-ray structures being studied by Rosalind Franklin. According to the model, DNA is composed of two strands of nucleotides coiled around each other, linked together by hydrogen bonds and running in opposite directions. Each strand is composed of four complementary nucleotides – adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T) – with an A on one strand always paired with T on the other, and C always paired with G. They proposed that such a structure allowed each strand to be used to reconstruct the other, an idea central to the passing on of hereditary information between generations.[28]

The foundation for sequencing proteins was first laid by the work of Frederick Sanger who by 1955 had completed the sequence of all the amino acids in insulin, a small protein secreted by the pancreas. This provided the first conclusive evidence that proteins were chemical entities with a specific molecular pattern rather than a random mixture of material suspended in fluid. Sanger's success in sequencing insulin spurred on x-ray crystallographers, including Watson and Crick, who by now were trying to understand how DNA directed the formation of proteins within a cell. Soon after attending a series of lectures given by Frederick Sanger in October 1954, Crick began developing a theory which argued that the arrangement of nucleotides in DNA determined the sequence of amino acids in proteins, which in turn helped determine the function of a protein. He published this theory in 1958.[29]

RNA sequencing

[edit]RNA sequencing was one of the earliest forms of nucleotide sequencing. The major landmark of RNA sequencing is the sequence of the first complete gene and the complete genome of Bacteriophage MS2, identified and published by Walter Fiers and his coworkers at the University of Ghent (Ghent, Belgium), in 1972[30] and 1976.[31] Traditional RNA sequencing methods require the creation of a cDNA molecule which must be sequenced.[32]

Early DNA sequencing methods

[edit]The first method for determining DNA sequences involved a location-specific primer extension strategy established by Ray Wu, a geneticist, at Cornell University in 1970.[33] DNA polymerase catalysis and specific nucleotide labeling, both of which figure prominently in current sequencing schemes, were used to sequence the cohesive ends of lambda phage DNA.[34][35][36] Between 1970 and 1973, Wu, scientist Radha Padmanabhan and colleagues demonstrated that this method can be employed to determine any DNA sequence using synthetic location-specific primers.[37][38][8]

Walter Gilbert, a biochemist, and Allan Maxam, a molecular geneticist, at Harvard also developed sequencing methods, including one for "DNA sequencing by chemical degradation".[39][40] In 1973, Gilbert and Maxam reported the sequence of 24 basepairs using a method known as wandering-spot analysis.[41] Advancements in sequencing were aided by the concurrent development of recombinant DNA technology, allowing DNA samples to be isolated from sources other than viruses.[42]

Two years later in 1975, Frederick Sanger, a biochemist, and Alan Coulson, a genome scientist, developed a method to sequence DNA.[43] The technique known as the "Plus and Minus" method, involved supplying all the components of the DNA but excluding the reaction of one of the four bases needed to complete the DNA.[44]

In 1976, Gilbert and Maxam, invented a method for rapidly sequencing DNA while at Harvard, known as the Maxam–Gilbert sequencing.[45] The technique involved treating radiolabelled DNA with a chemical and using a polyacrylamide gel to determine the sequence.[46]

In 1977, Sanger then adopted a primer-extension strategy to develop more rapid DNA sequencing methods at the MRC Centre, Cambridge, UK. This technique was similar to his "Plus and Minus" strategy, however, it was based upon the selective incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) by DNA polymerase during in vitro DNA replication.[47][46][48] Sanger published this method in the same year.[49]

Sequencing of full genomes

[edit]

The first full DNA genome to be sequenced was that of bacteriophage φX174 in 1977.[50] Medical Research Council scientists deciphered the complete DNA sequence of the Epstein-Barr virus in 1984, finding it contained 172,282 nucleotides. Completion of the sequence marked a significant turning point in DNA sequencing because it was achieved with no prior genetic profile knowledge of the virus.[51][8]

A non-radioactive method for transferring the DNA molecules of sequencing reaction mixtures onto an immobilizing matrix during electrophoresis was developed by Herbert Pohl and co-workers in the early 1980s.[52][53] Followed by the commercialization of the DNA sequencer "Direct-Blotting-Electrophoresis-System GATC 1500" by GATC Biotech, which was intensively used in the framework of the EU genome-sequencing programme, the complete DNA sequence of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome II.[54] Leroy E. Hood's laboratory at the California Institute of Technology announced the first semi-automated DNA sequencing machine in 1986.[55] This was followed by Applied Biosystems' marketing of the first fully automated sequencing machine, the ABI 370, in 1987 and by Dupont's Genesis 2000[56] which used a novel fluorescent labeling technique enabling all four dideoxynucleotides to be identified in a single lane. By 1990, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) had begun large-scale sequencing trials on Mycoplasma capricolum, Escherichia coli, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae at a cost of US$0.75 per base. Meanwhile, sequencing of human cDNA sequences called expressed sequence tags began in Craig Venter's lab, an attempt to capture the coding fraction of the human genome.[57] In 1995, Venter, Hamilton Smith, and colleagues at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) published the first complete genome of a free-living organism, the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae. The circular chromosome contains 1,830,137 bases and its publication in the journal Science[58] marked the first published use of whole-genome shotgun sequencing, eliminating the need for initial mapping efforts.

By 2003, the Human Genome Project's shotgun sequencing methods had been used to produce a draft sequence of the human genome; it had a 92% accuracy.[59][60][61] In 2022, scientists successfully sequenced the last 8% of the human genome. The fully sequenced standard reference gene is called GRCh38.p14, and it contains 3.1 billion base pairs.[62][63]

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) methods

[edit]

Several new methods for DNA sequencing were developed in the mid to late 1990s and were implemented in commercial DNA sequencers by 2000. Together these were called the "next-generation" or "second-generation" sequencing (NGS) methods, in order to distinguish them from the earlier methods, including Sanger sequencing. In contrast to the first generation of sequencing, NGS technology is typically characterized by being highly scalable, allowing the entire genome to be sequenced at once. Usually, this is accomplished by fragmenting the genome into small pieces, randomly sampling for a fragment, and sequencing it using one of a variety of technologies, such as those described below. An entire genome is possible because multiple fragments are sequenced at once (giving it the name "massively parallel" sequencing) in an automated process. [citation needed]

NGS technology has tremendously empowered researchers to look for insights into health, anthropologists to investigate human origins, and is catalyzing the "Personalized Medicine" movement. However, it has also opened the door to more room for error. There are many software tools to carry out the computational analysis of NGS data, often compiled at online platforms such as CSI NGS Portal, each with its own algorithm. Even the parameters within one software package can change the outcome of the analysis. In addition, the large quantities of data produced by DNA sequencing have also required development of new methods and programs for sequence analysis. Several efforts to develop standards in the NGS field have been attempted to address these challenges, most of which have been small-scale efforts arising from individual labs. Most recently, a large, organized, FDA-funded effort has culminated in the BioCompute standard.[65]

On 26 October 1990, Roger Tsien, Pepi Ross, Margaret Fahnestock and Allan J Johnston filed a patent describing stepwise ("base-by-base") sequencing with removable 3' blockers on DNA arrays (blots and single DNA molecules).[66] In 1996, Pål Nyrén and his student Mostafa Ronaghi at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm published their method of pyrosequencing.[67]

On 1 April 1997, Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli submitted patents to the World Intellectual Property Organization describing DNA colony sequencing.[68] The DNA sample preparation and random surface-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) arraying methods described in this patent, coupled to Roger Tsien et al.'s "base-by-base" sequencing method, is now implemented in Illumina's Hi-Seq genome sequencers. [citation needed]

In 1998, Phil Green and Brent Ewing of the University of Washington described their phred quality score for sequencer data analysis,[69] a landmark analysis technique that gained widespread adoption, and which is still the most common metric for assessing the accuracy of a sequencing platform.[70]

Lynx Therapeutics published and marketed massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS), in 2000. This method incorporated a parallelized, adapter/ligation-mediated, bead-based sequencing technology and served as the first commercially available "next-generation" sequencing method, though no DNA sequencers were sold to independent laboratories.[71]

Basic methods

[edit]Maxam-Gilbert sequencing

[edit]Allan Maxam and Walter Gilbert published a DNA sequencing method in 1977 based on chemical modification of DNA and subsequent cleavage at specific bases.[39] Also known as chemical sequencing, this method allowed purified samples of double-stranded DNA to be used without further cloning. This method's use of radioactive labeling and its technical complexity discouraged extensive use after refinements in the Sanger methods had been made. [citation needed]

Maxam-Gilbert sequencing requires radioactive labeling at one 5' end of the DNA and purification of the DNA fragment to be sequenced. Chemical treatment then generates breaks at a small proportion of one or two of the four nucleotide bases in each of four reactions (G, A+G, C, C+T). The concentration of the modifying chemicals is controlled to introduce on average one modification per DNA molecule. Thus a series of labeled fragments is generated, from the radiolabeled end to the first "cut" site in each molecule. The fragments in the four reactions are electrophoresed side by side in denaturing acrylamide gels for size separation. To visualize the fragments, the gel is exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography, yielding a series of dark bands each corresponding to a radiolabeled DNA fragment, from which the sequence may be inferred.[39]

This method is mostly obsolete as of 2023.[72]

Chain-termination methods

[edit]The chain-termination method developed by Frederick Sanger and coworkers in 1977 soon became the method of choice, owing to its relative ease and reliability.[49][73] When invented, the chain-terminator method used fewer toxic chemicals and lower amounts of radioactivity than the Maxam and Gilbert method. Because of its comparative ease, the Sanger method was soon automated and was the method used in the first generation of DNA sequencers. [citation needed]

Sanger sequencing is the method which prevailed from the 1980s until the mid-2000s. Over that period, great advances were made in the technique, such as fluorescent labelling, capillary electrophoresis, and general automation. These developments allowed much more efficient sequencing, leading to lower costs. The Sanger method, in mass production form, is the technology which produced the first human genome in 2001, ushering in the age of genomics. However, later in the decade, radically different approaches reached the market, bringing the cost per genome down from $100 million in 2001 to $10,000 in 2011.[74]

Sequencing by synthesis

[edit]The objective for sequential sequencing by synthesis (SBS) is to determine the sequencing of a DNA sample by detecting the incorporation of a nucleotide by a DNA polymerase. An engineered polymerase is used to synthesize a copy of a single strand of DNA and the incorporation of each nucleotide is monitored. The principle of real-time sequencing by synthesis was first described in 1993[75] with improvements published some years later.[76] The key parts are highly similar for all embodiments of SBS and includes (1) amplification of DNA (to enhance the subsequent signal) and attach the DNA to be sequenced to a solid support, (2) generation of single stranded DNA on the solid support, (3) incorporation of nucleotides using an engineered polymerase and (4) real-time detection of the incorporation of nucleotide The steps 3-4 are repeated and the sequence is assembled from the signals obtained in step 4. This principle of real-time sequencing-by-synthesis has been used for almost all massive parallel sequencing instruments, including 454, PacBio, IonTorrent, Illumina and MGI. [citation needed]

Large-scale sequencing and de novo sequencing

[edit]

Large-scale sequencing often aims at sequencing very long DNA pieces, such as whole chromosomes, although large-scale sequencing can also be used to generate very large numbers of short sequences, such as found in phage display. For longer targets such as chromosomes, common approaches consist of cutting (with restriction enzymes) or shearing (with mechanical forces) large DNA fragments into shorter DNA fragments. The fragmented DNA may then be cloned into a DNA vector and amplified in a bacterial host such as Escherichia coli. Short DNA fragments purified from individual bacterial colonies are individually sequenced and assembled electronically into one long, contiguous sequence. Studies have shown that adding a size selection step to collect DNA fragments of uniform size can improve sequencing efficiency and accuracy of the genome assembly. In these studies, automated sizing has proven to be more reproducible and precise than manual gel sizing.[77][78][79]

The term "de novo sequencing" specifically refers to methods used to determine the sequence of DNA with no previously known sequence. De novo translates from Latin as "from the beginning". Gaps in the assembled sequence may be filled by primer walking. The different strategies have different tradeoffs in speed and accuracy; shotgun methods are often used for sequencing large genomes, but its assembly is complex and difficult, particularly with sequence repeats often causing gaps in genome assembly. [citation needed]

Most sequencing approaches use an in vitro cloning step to amplify individual DNA molecules, because their molecular detection methods are not sensitive enough for single molecule sequencing. Emulsion PCR[80] isolates individual DNA molecules along with primer-coated beads in aqueous droplets within an oil phase. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) then coats each bead with clonal copies of the DNA molecule followed by immobilization for later sequencing. Emulsion PCR is used in the methods developed by Marguilis et al. (commercialized by 454 Life Sciences), Shendure and Porreca et al. (also known as "polony sequencing") and SOLiD sequencing, (developed by Agencourt, later Applied Biosystems, now Life Technologies).[81][82][83] Emulsion PCR is also used in the GemCode and Chromium platforms developed by 10x Genomics.[84]

Shotgun sequencing

[edit]Shotgun sequencing is a sequencing method designed for analysis of DNA sequences longer than 1000 base pairs, up to and including entire chromosomes. This method requires the target DNA to be broken into random fragments. After sequencing individual fragments using the chain termination method, the sequences can be reassembled on the basis of their overlapping regions.[85]

High-throughput methods

[edit]

High-throughput sequencing, which includes next-generation "short-read" and third-generation "long-read" sequencing methods,[nt 1] applies to exome sequencing, genome sequencing, genome resequencing, transcriptome profiling (RNA-Seq), DNA-protein interactions (ChIP-sequencing), and epigenome characterization.[86]

The high demand for low-cost sequencing has driven the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies that parallelize the sequencing process, producing thousands or millions of sequences concurrently.[87][88][89] High-throughput sequencing technologies are intended to lower the cost of DNA sequencing beyond what is possible with standard dye-terminator methods.[90] In ultra-high-throughput sequencing as many as 500,000 sequencing-by-synthesis operations may be run in parallel.[91][92][93] Such technologies led to the ability to sequence an entire human genome in as little as one day.[94] As of 2019[update], corporate leaders in the development of high-throughput sequencing products included Illumina, Qiagen and ThermoFisher Scientific.[94]

| Method | Read length | Accuracy (single read not consensus) | Reads per run | Time per run | Cost per 1 billion bases (in US$) | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-molecule real-time sequencing (Pacific Biosciences) | 30,000 bp (N50); | 87% raw-read accuracy[100] | 4,000,000 per Sequel 2 SMRT cell, 100–200 gigabases[97][101][102] | 30 minutes to 20 hours[97][103] | $7.2-$43.3 | Fast. Detects 4mC, 5mC, 6mA.[104] | Moderate throughput. Equipment can be very expensive. |

| Ion semiconductor (Ion Torrent sequencing) | up to 600 bp[105] | 99.6%[106] | up to 80 million | 2 hours | $66.8-$950 | Less expensive equipment. Fast. | Homopolymer errors. |

| Pyrosequencing (454) | 700 bp | 99.9% | 1 million | 24 hours | $10,000 | Long read size. Fast. | Runs are expensive. Homopolymer errors. |

| Sequencing by synthesis (Illumina) | MiniSeq, NextSeq: 75–300 bp;

MiSeq: 50–600 bp; HiSeq 2500: 50–500 bp; HiSeq 3/4000: 50–300 bp; HiSeq X: 300 bp |

99.9% (Phred30) | MiniSeq/MiSeq: 1–25 Million;

NextSeq: 130-00 Million; HiSeq 2500: 300 million – 2 billion; HiSeq 3/4000 2.5 billion; HiSeq X: 3 billion |

1 to 11 days, depending upon sequencer and specified read length[107] | $5 to $150 | Potential for high sequence yield, depending upon sequencer model and desired application. | Equipment can be very expensive. Requires high concentrations of DNA. |

| Combinatorial probe anchor synthesis (cPAS- BGI/MGI) | BGISEQ-50: 35-50bp;

MGISEQ 200: 50-200bp; BGISEQ-500, MGISEQ-2000: 50-300bp[108] |

99.9% (Phred30) | BGISEQ-50: 160M;

MGISEQ 200: 300M; BGISEQ-500: 1300M per flow cell; MGISEQ-2000: 375M FCS flow cell, 1500M FCL flow cell per flow cell. |

1 to 9 days depending on instrument, read length and number of flow cells run at a time. | $5– $120 | ||

| Sequencing by ligation (SOLiD sequencing) | 50+35 or 50+50 bp | 99.9% | 1.2 to 1.4 billion | 1 to 2 weeks | $60–130 | Low cost per base. | Slower than other methods. Has issues sequencing palindromic sequences.[109] |

| Nanopore Sequencing | Dependent on library preparation, not the device, so user chooses read length (up to 2,272,580 bp reported[110]). | ~92–97% single read | dependent on read length selected by user | data streamed in real time. Choose 1 min to 48 hrs | $7–100 | Longest individual reads. Accessible user community. Portable (Palm sized). | Lower throughput than other machines, Single read accuracy in 90s. |

| GenapSys Sequencing | Around 150 bp single-end | 99.9% (Phred30) | 1 to 16 million | Around 24 hours | $667 | Low-cost of instrument ($10,000) | |

| Chain termination (Sanger sequencing) | 400 to 900 bp | 99.9% | N/A | 20 minutes to 3 hours | $2,400,000 | Useful for many applications. | More expensive and impractical for larger sequencing projects. This method also requires the time-consuming step of plasmid cloning or PCR. |

Long-read sequencing methods

[edit]Single molecule real time (SMRT) sequencing

[edit]SMRT sequencing is based on the sequencing by synthesis approach. The DNA is synthesized in zero-mode wave-guides (ZMWs) – small well-like containers with the capturing tools located at the bottom of the well. The sequencing is performed with use of unmodified polymerase (attached to the ZMW bottom) and fluorescently labelled nucleotides flowing freely in the solution. The wells are constructed in a way that only the fluorescence occurring by the bottom of the well is detected. The fluorescent label is detached from the nucleotide upon its incorporation into the DNA strand, leaving an unmodified DNA strand. According to Pacific Biosciences (PacBio), the SMRT technology developer, this methodology allows detection of nucleotide modifications (such as cytosine methylation). This happens through the observation of polymerase kinetics. This approach allows reads of 20,000 nucleotides or more, with average read lengths of 5 kilobases.[101][111] In 2015, Pacific Biosciences announced the launch of a new sequencing instrument called the Sequel System, with 1 million ZMWs compared to 150,000 ZMWs in the PacBio RS II instrument.[112][113] SMRT sequencing is referred to as "third-generation" or "long-read" sequencing. [citation needed]

Nanopore DNA sequencing

[edit]The DNA passing through the nanopore changes its ion current. This change is dependent on the shape, size and length of the DNA sequence. Each type of the nucleotide blocks the ion flow through the pore for a different period of time. The method does not require modified nucleotides and is performed in real time. Nanopore sequencing is referred to as "third-generation" or "long-read" sequencing, along with SMRT sequencing. [citation needed]

Early industrial research into this method was based on a technique called 'exonuclease sequencing', where the readout of electrical signals occurred as nucleotides passed by alpha(α)-hemolysin pores covalently bound with cyclodextrin.[114] However the subsequent commercial method, 'strand sequencing', sequenced DNA bases in an intact strand. [citation needed]

Two main areas of nanopore sequencing in development are solid state nanopore sequencing, and protein based nanopore sequencing. Protein nanopore sequencing utilizes membrane protein complexes such as α-hemolysin, MspA (Mycobacterium smegmatis Porin A) or CssG, which show great promise given their ability to distinguish between individual and groups of nucleotides.[115] In contrast, solid-state nanopore sequencing utilizes synthetic materials such as silicon nitride and aluminum oxide and it is preferred for its superior mechanical ability and thermal and chemical stability.[116] The fabrication method is essential for this type of sequencing given that the nanopore array can contain hundreds of pores with diameters smaller than eight nanometers.[115]

The concept originated from the idea that single stranded DNA or RNA molecules can be electrophoretically driven in a strict linear sequence through a biological pore that can be less than eight nanometers, and can be detected given that the molecules release an ionic current while moving through the pore. The pore contains a detection region capable of recognizing different bases, with each base generating various time specific signals corresponding to the sequence of bases as they cross the pore which are then evaluated.[116] Precise control over the DNA transport through the pore is crucial for success. Various enzymes such as exonucleases and polymerases have been used to moderate this process by positioning them near the pore's entrance.[117]

Short-read sequencing methods

[edit]Massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS)

[edit]The first of the high-throughput sequencing technologies, massively parallel signature sequencing (or MPSS, also called next generation sequencing), was developed in the 1990s at Lynx Therapeutics, a company founded in 1992 by Sydney Brenner and Sam Eletr. MPSS was a bead-based method that used a complex approach of adapter ligation followed by adapter decoding, reading the sequence in increments of four nucleotides. This method made it susceptible to sequence-specific bias or loss of specific sequences. Because the technology was so complex, MPSS was only performed 'in-house' by Lynx Therapeutics and no DNA sequencing machines were sold to independent laboratories. Lynx Therapeutics merged with Solexa (later acquired by Illumina) in 2004, leading to the development of sequencing-by-synthesis, a simpler approach acquired from Manteia Predictive Medicine, which rendered MPSS obsolete. However, the essential properties of the MPSS output were typical of later high-throughput data types, including hundreds of thousands of short DNA sequences. In the case of MPSS, these were typically used for sequencing cDNA for measurements of gene expression levels.[71]

Polony sequencing

[edit]The polony sequencing method, developed in the laboratory of George M. Church at Harvard, was among the first high-throughput sequencing systems and was used to sequence a full E. coli genome in 2005.[82] It combined an in vitro paired-tag library with emulsion PCR, an automated microscope, and ligation-based sequencing chemistry to sequence an E. coli genome at an accuracy of >99.9999% and a cost approximately 1/9 that of Sanger sequencing.[82] The technology was licensed to Agencourt Biosciences, subsequently spun out into Agencourt Personal Genomics, and eventually incorporated into the Applied Biosystems SOLiD platform. Applied Biosystems was later acquired by Life Technologies, now part of Thermo Fisher Scientific. [citation needed]

454 pyrosequencing

[edit]A parallelized version of pyrosequencing was developed by 454 Life Sciences, which has since been acquired by Roche Diagnostics. The method amplifies DNA inside water droplets in an oil solution (emulsion PCR), with each droplet containing a single DNA template attached to a single primer-coated bead that then forms a clonal colony. The sequencing machine contains many picoliter-volume wells each containing a single bead and sequencing enzymes. Pyrosequencing uses luciferase to generate light for detection of the individual nucleotides added to the nascent DNA, and the combined data are used to generate sequence reads.[81] This technology provides intermediate read length and price per base compared to Sanger sequencing on one end and Solexa and SOLiD on the other.[90]

Illumina (Solexa) sequencing

[edit]Solexa, now part of Illumina, was founded by Shankar Balasubramanian and David Klenerman in 1998, and developed a sequencing method based on reversible dye-terminators technology, and engineered polymerases.[118] The reversible terminated chemistry concept was invented by Bruno Canard and Simon Sarfati at the Pasteur Institute in Paris.[119][120] It was developed internally at Solexa by those named on the relevant patents. In 2004, Solexa acquired the company Manteia Predictive Medicine in order to gain a massively parallel sequencing technology invented in 1997 by Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli.[68] It is based on "DNA clusters" or "DNA colonies", which involves the clonal amplification of DNA on a surface. The cluster technology was co-acquired with Lynx Therapeutics of California. Solexa Ltd. later merged with Lynx to form Solexa Inc. [citation needed]

In this method, DNA molecules and primers are first attached on a slide or flow cell and amplified with polymerase so that local clonal DNA colonies, later coined "DNA clusters", are formed. To determine the sequence, four types of reversible terminator bases (RT-bases) are added and non-incorporated nucleotides are washed away. A camera takes images of the fluorescently labeled nucleotides. Then the dye, along with the terminal 3' blocker, is chemically removed from the DNA, allowing for the next cycle to begin. Unlike pyrosequencing, the DNA chains are extended one nucleotide at a time and image acquisition can be performed at a delayed moment, allowing for very large arrays of DNA colonies to be captured by sequential images taken from a single camera. [citation needed]

Decoupling the enzymatic reaction and the image capture allows for optimal throughput and theoretically unlimited sequencing capacity. With an optimal configuration, the ultimately reachable instrument throughput is thus dictated solely by the analog-to-digital conversion rate of the camera, multiplied by the number of cameras and divided by the number of pixels per DNA colony required for visualizing them optimally (approximately 10 pixels/colony). In 2012, with cameras operating at more than 10 MHz A/D conversion rates and available optics, fluidics and enzymatics, throughput can be multiples of 1 million nucleotides/second, corresponding roughly to 1 human genome equivalent at 1x coverage per hour per instrument, and 1 human genome re-sequenced (at approx. 30x) per day per instrument (equipped with a single camera).[121]

Combinatorial probe anchor synthesis (cPAS)

[edit]This method is an upgraded modification to combinatorial probe anchor ligation technology (cPAL) described by Complete Genomics[122] which has since become part of Chinese genomics company BGI in 2013.[123] The two companies have refined the technology to allow for longer read lengths, reaction time reductions and faster time to results. In addition, data are now generated as contiguous full-length reads in the standard FASTQ file format and can be used as-is in most short-read-based bioinformatics analysis pipelines.[124][125]

The two technologies that form the basis for this high-throughput sequencing technology are DNA nanoballs (DNB) and patterned arrays for nanoball attachment to a solid surface.[122] DNA nanoballs are simply formed by denaturing double stranded, adapter ligated libraries and ligating the forward strand only to a splint oligonucleotide to form a ssDNA circle. Faithful copies of the circles containing the DNA insert are produced utilizing Rolling Circle Amplification that generates approximately 300–500 copies. The long strand of ssDNA folds upon itself to produce a three-dimensional nanoball structure that is approximately 220 nm in diameter. Making DNBs replaces the need to generate PCR copies of the library on the flow cell and as such can remove large proportions of duplicate reads, adapter-adapter ligations and PCR induced errors.[124][126]

The patterned array of positively charged spots is fabricated through photolithography and etching techniques followed by chemical modification to generate a sequencing flow cell. Each spot on the flow cell is approximately 250 nm in diameter, are separated by 700 nm (centre to centre) and allows easy attachment of a single negatively charged DNB to the flow cell and thus reducing under or over-clustering on the flow cell.[122][127]

Sequencing is then performed by addition of an oligonucleotide probe that attaches in combination to specific sites within the DNB. The probe acts as an anchor that then allows one of four single reversibly inactivated, labelled nucleotides to bind after flowing across the flow cell. Unbound nucleotides are washed away before laser excitation of the attached labels then emit fluorescence and signal is captured by cameras that is converted to a digital output for base calling. The attached base has its terminator and label chemically cleaved at completion of the cycle. The cycle is repeated with another flow of free, labelled nucleotides across the flow cell to allow the next nucleotide to bind and have its signal captured. This process is completed a number of times (usually 50 to 300 times) to determine the sequence of the inserted piece of DNA at a rate of approximately 40 million nucleotides per second as of 2018.[citation needed]

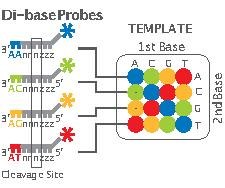

SOLiD sequencing

[edit]

Applied Biosystems' (now a Life Technologies brand) SOLiD technology employs sequencing by ligation. Here, a pool of all possible oligonucleotides of a fixed length are labeled according to the sequenced position. Oligonucleotides are annealed and ligated; the preferential ligation by DNA ligase for matching sequences results in a signal informative of the nucleotide at that position. Each base in the template is sequenced twice, and the resulting data are decoded according to the 2 base encoding scheme used in this method. Before sequencing, the DNA is amplified by emulsion PCR. The resulting beads, each containing single copies of the same DNA molecule, are deposited on a glass slide.[128] The result is sequences of quantities and lengths comparable to Illumina sequencing.[90] This sequencing by ligation method has been reported to have some issue sequencing palindromic sequences.[109]

Ion Torrent semiconductor sequencing

[edit]Ion Torrent Systems Inc. (now owned by Life Technologies) developed a system based on using standard sequencing chemistry, but with a novel, semiconductor-based detection system. This method of sequencing is based on the detection of hydrogen ions that are released during the polymerisation of DNA, as opposed to the optical methods used in other sequencing systems. A microwell containing a template DNA strand to be sequenced is flooded with a single type of nucleotide. If the introduced nucleotide is complementary to the leading template nucleotide it is incorporated into the growing complementary strand. This causes the release of a hydrogen ion that triggers a hypersensitive ion sensor, which indicates that a reaction has occurred. If homopolymer repeats are present in the template sequence, multiple nucleotides will be incorporated in a single cycle. This leads to a corresponding number of released hydrogens and a proportionally higher electronic signal.[129]

DNA nanoball sequencing

[edit]DNA nanoball sequencing is a type of high throughput sequencing technology used to determine the entire genomic sequence of an organism. The company Complete Genomics uses this technology to sequence samples submitted by independent researchers. The method uses rolling circle replication to amplify small fragments of genomic DNA into DNA nanoballs. Unchained sequencing by ligation is then used to determine the nucleotide sequence.[130] This method of DNA sequencing allows large numbers of DNA nanoballs to be sequenced per run and at low reagent costs compared to other high-throughput sequencing platforms.[131] However, only short sequences of DNA are determined from each DNA nanoball which makes mapping the short reads to a reference genome difficult.[130]

Heliscope single molecule sequencing

[edit]Heliscope sequencing is a method of single-molecule sequencing developed by Helicos Biosciences. It uses DNA fragments with added poly-A tail adapters which are attached to the flow cell surface. The next steps involve extension-based sequencing with cyclic washes of the flow cell with fluorescently labeled nucleotides (one nucleotide type at a time, as with the Sanger method). The reads are performed by the Heliscope sequencer.[132][133] The reads are short, averaging 35 bp.[134] What made this technology especially novel was that it was the first of its class to sequence non-amplified DNA, thus preventing any read errors associated with amplification steps.[46] In 2009 a human genome was sequenced using the Heliscope, however in 2012 the company went bankrupt.[135]

Microfluidic systems

[edit]There are two main microfluidic systems that are used to sequence DNA; droplet based microfluidics and digital microfluidics. Microfluidic devices solve many of the current limitations of current sequencing arrays. [citation needed]

Abate et al. studied the use of droplet-based microfluidic devices for DNA sequencing.[4] These devices have the ability to form and process picoliter sized droplets at the rate of thousands per second. The devices were created from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and used Forster resonance energy transfer, FRET assays to read the sequences of DNA encompassed in the droplets. Each position on the array tested for a specific 15 base sequence.[4]

Fair et al. used digital microfluidic devices to study DNA pyrosequencing.[136] Significant advantages include the portability of the device, reagent volume, speed of analysis, mass manufacturing abilities, and high throughput. This study provided a proof of concept showing that digital devices can be used for pyrosequencing; the study included using synthesis, which involves the extension of the enzymes and addition of labeled nucleotides.[136]

Boles et al. also studied pyrosequencing on digital microfluidic devices.[137] They used an electro-wetting device to create, mix, and split droplets. The sequencing uses a three-enzyme protocol and DNA templates anchored with magnetic beads. The device was tested using two protocols and resulted in 100% accuracy based on raw pyrogram levels. The advantages of these digital microfluidic devices include size, cost, and achievable levels of functional integration.[137]

DNA sequencing research, using microfluidics, also has the ability to be applied to the sequencing of RNA, using similar droplet microfluidic techniques, such as the method, inDrops.[138] This shows that many of these DNA sequencing techniques will be able to be applied further and be used to understand more about genomes and transcriptomes. [citation needed]

Methods in development

[edit]DNA sequencing methods currently under development include reading the sequence as a DNA strand transits through nanopores (a method that is now commercial but subsequent generations such as solid-state nanopores are still in development),[139][140] and microscopy-based techniques, such as atomic force microscopy or transmission electron microscopy that are used to identify the positions of individual nucleotides within long DNA fragments (>5,000 bp) by nucleotide labeling with heavier elements (e.g., halogens) for visual detection and recording.[141][142] Third generation technologies aim to increase throughput and decrease the time to result and cost by eliminating the need for excessive reagents and harnessing the processivity of DNA polymerase.[143]

Tunnelling currents DNA sequencing

[edit]Another approach uses measurements of the electrical tunnelling currents across single-strand DNA as it moves through a channel. Depending on its electronic structure, each base affects the tunnelling current differently,[144] allowing differentiation between different bases.[145]

The use of tunnelling currents has the potential to sequence orders of magnitude faster than ionic current methods and the sequencing of several DNA oligomers and micro-RNA has already been achieved.[146]

Sequencing by hybridization

[edit]Sequencing by hybridization is a non-enzymatic method that uses a DNA microarray. A single pool of DNA whose sequence is to be determined is fluorescently labeled and hybridized to an array containing known sequences. Strong hybridization signals from a given spot on the array identifies its sequence in the DNA being sequenced.[147]

This method of sequencing utilizes binding characteristics of a library of short single stranded DNA molecules (oligonucleotides), also called DNA probes, to reconstruct a target DNA sequence. Non-specific hybrids are removed by washing and the target DNA is eluted.[148] Hybrids are re-arranged such that the DNA sequence can be reconstructed. The benefit of this sequencing type is its ability to capture a large number of targets with a homogenous coverage.[149] A large number of chemicals and starting DNA is usually required. However, with the advent of solution-based hybridization, much less equipment and chemicals are necessary.[148]

Sequencing with mass spectrometry

[edit]Mass spectrometry may be used to determine DNA sequences. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, or MALDI-TOF MS, has specifically been investigated as an alternative method to gel electrophoresis for visualizing DNA fragments. With this method, DNA fragments generated by chain-termination sequencing reactions are compared by mass rather than by size. The mass of each nucleotide is different from the others and this difference is detectable by mass spectrometry. Single-nucleotide mutations in a fragment can be more easily detected with MS than by gel electrophoresis alone. MALDI-TOF MS can more easily detect differences between RNA fragments, so researchers may indirectly sequence DNA with MS-based methods by converting it to RNA first.[150]

The higher resolution of DNA fragments permitted by MS-based methods is of special interest to researchers in forensic science, as they may wish to find single-nucleotide polymorphisms in human DNA samples to identify individuals. These samples may be highly degraded so forensic researchers often prefer mitochondrial DNA for its higher stability and applications for lineage studies. MS-based sequencing methods have been used to compare the sequences of human mitochondrial DNA from samples in a Federal Bureau of Investigation database[151] and from bones found in mass graves of World War I soldiers.[152]

Early chain-termination and TOF MS methods demonstrated read lengths of up to 100 base pairs.[153] Researchers have been unable to exceed this average read size; like chain-termination sequencing alone, MS-based DNA sequencing may not be suitable for large de novo sequencing projects. Even so, a 2010 study did use the short sequence reads and mass spectroscopy to compare single-nucleotide polymorphisms in pathogenic Streptococcus strains.[154]

Microfluidic Sanger sequencing

[edit]In microfluidic Sanger sequencing the entire thermocycling amplification of DNA fragments as well as their separation by electrophoresis is done on a single glass wafer (approximately 10 cm in diameter) thus reducing the reagent usage as well as cost.[155] In some instances researchers have shown that they can increase the throughput of conventional sequencing through the use of microchips.[156] Research will still need to be done in order to make this use of technology effective. [citation needed]

Microscopy-based techniques

[edit]This approach directly visualizes the sequence of DNA molecules using electron microscopy. The first identification of DNA base pairs within intact DNA molecules by enzymatically incorporating modified bases, which contain atoms of increased atomic number, direct visualization and identification of individually labeled bases within a synthetic 3,272 base-pair DNA molecule and a 7,249 base-pair viral genome has been demonstrated.[157]

RNAP sequencing

[edit]This method is based on use of RNA polymerase (RNAP), which is attached to a polystyrene bead. One end of DNA to be sequenced is attached to another bead, with both beads being placed in optical traps. RNAP motion during transcription brings the beads in closer and their relative distance changes, which can then be recorded at a single nucleotide resolution. The sequence is deduced based on the four readouts with lowered concentrations of each of the four nucleotide types, similarly to the Sanger method.[158] A comparison is made between regions and sequence information is deduced by comparing the known sequence regions to the unknown sequence regions.[158]

In vitro virus high-throughput sequencing

[edit]A method has been developed to analyze full sets of protein interactions using a combination of 454 pyrosequencing and an in vitro virus mRNA display method. Specifically, this method covalently links proteins of interest to the mRNAs encoding them, then detects the mRNA pieces using reverse transcription PCRs. The mRNA may then be amplified and sequenced. The combined method was titled IVV-HiTSeq and can be performed under cell-free conditions, though its results may not be representative of in vivo conditions.[159]

Market share

[edit]While there are many different ways to sequence DNA, only a few dominate the market. In 2022, Illumina had about 80% of the market; the rest of the market is taken by only a few players (PacBio, Oxford, 454, MGI)[160]

Sample preparation

[edit]The success of any DNA sequencing protocol relies upon the DNA or RNA sample extraction and preparation from the biological material of interest. [citation needed]

- A successful DNA extraction will yield a DNA sample with long, non-degraded strands.

- A successful RNA extraction will yield a RNA sample that should be converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase—a DNA polymerase that synthesizes a complementary DNA based on existing strands of RNA in a PCR-like manner.[161] Complementary DNA can then be processed the same way as genomic DNA.

After DNA or RNA extraction, samples may require further preparation depending on the sequencing method. For Sanger sequencing, either cloning procedures or PCR are required prior to sequencing. In the case of next-generation sequencing methods, library preparation is required before processing.[162] Assessing the quality and quantity of nucleic acids both after extraction and after library preparation identifies degraded, fragmented, and low-purity samples and yields high-quality sequencing data.[163]

Development initiatives

[edit]

In October 2006, the X Prize Foundation established an initiative to promote the development of full genome sequencing technologies, called the Archon X Prize, intending to award $10 million to "the first Team that can build a device and use it to sequence 100 human genomes within 10 days or less, with an accuracy of no more than one error in every 100,000 bases sequenced, with sequences accurately covering at least 98% of the genome, and at a recurring cost of no more than $10,000 (US) per genome."[164]

Each year the National Human Genome Research Institute, or NHGRI, promotes grants for new research and developments in genomics. 2010 grants and 2011 candidates include continuing work in microfluidic, polony and base-heavy sequencing methodologies.[165]

Computational challenges

[edit]The sequencing technologies described here produce raw data that needs to be assembled into longer sequences such as complete genomes (sequence assembly). There are many computational challenges to achieve this, such as the evaluation of the raw sequence data which is done by programs and algorithms such as Phred and Phrap. Other challenges have to deal with repetitive sequences that often prevent complete genome assemblies because they occur in many places of the genome. As a consequence, many sequences may not be assigned to particular chromosomes. The production of raw sequence data is only the beginning of its detailed bioinformatical analysis.[166] Yet new methods for sequencing and correcting sequencing errors were developed.[167]

Read trimming

[edit]Sometimes, the raw reads produced by the sequencer are correct and precise only in a fraction of their length. Using the entire read may introduce artifacts in the downstream analyses like genome assembly, SNP calling, or gene expression estimation. Two classes of trimming programs have been introduced, based on the window-based or the running-sum classes of algorithms.[168] This is a partial list of the trimming algorithms currently available, specifying the algorithm class they belong to:

| Name of algorithm | Type of algorithm |

|---|---|

| Cutadapt[169] | Running sum |

| ConDeTri[170] | Window based |

| ERNE-FILTER[171] | Running sum |

| FASTX quality trimmer | Window based |

| PRINSEQ[172] | Window based |

| Trimmomatic[173] | Window based |

| SolexaQA[174] | Window based |

| SolexaQA-BWA | Running sum |

| Sickle | Window based |

Ethical issues

[edit]Human genetics have been included within the field of bioethics since the early 1970s[175] and the growth in the use of DNA sequencing (particularly high-throughput sequencing) has introduced a number of ethical issues. One key issue is the ownership of an individual's DNA and the data produced when that DNA is sequenced.[176] Regarding the DNA molecule itself, the leading legal case on this topic, Moore v. Regents of the University of California (1990) ruled that individuals have no property rights to discarded cells or any profits made using these cells (for instance, as a patented cell line). However, individuals have a right to informed consent regarding removal and use of cells. Regarding the data produced through DNA sequencing, Moore gives the individual no rights to the information derived from their DNA.[176]

As DNA sequencing becomes more widespread, the storage, security and sharing of genomic data has also become more important.[176][177] For instance, one concern is that insurers may use an individual's genomic data to modify their quote, depending on the perceived future health of the individual based on their DNA.[177][178] In May 2008, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) was signed in the United States, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of genetic information with respect to health insurance and employment.[179][180] In 2012, the US Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues reported that existing privacy legislation for DNA sequencing data such as GINA and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act were insufficient, noting that whole-genome sequencing data was particularly sensitive, as it could be used to identify not only the individual from which the data was created, but also their relatives.[181][182]

In most of the United States, DNA that is "abandoned", such as that found on a licked stamp or envelope, coffee cup, cigarette, chewing gum, household trash, or hair that has fallen on a public sidewalk, may legally be collected and sequenced by anyone, including the police, private investigators, political opponents, or people involved in paternity disputes. As of 2013, eleven states have laws that can be interpreted to prohibit "DNA theft".[183]

Ethical issues have also been raised by the increasing use of genetic variation screening, both in newborns, and in adults by companies such as 23andMe.[184][185] It has been asserted that screening for genetic variations can be harmful, increasing anxiety in individuals who have been found to have an increased risk of disease.[186] For example, in one case noted in Time, doctors screening an ill baby for genetic variants chose not to inform the parents of an unrelated variant linked to dementia due to the harm it would cause to the parents.[187] However, a 2011 study in The New England Journal of Medicine has shown that individuals undergoing disease risk profiling did not show increased levels of anxiety.[186] Also, the development of Next Generation sequencing technologies such as Nanopore based sequencing has also raised further ethical concerns.[188]

See also

[edit]- Bioinformatics – Computational analysis of large, complex sets of biological data

- Cancer genome sequencing

- Circular consensus sequencing

- DNA computing – Computing using molecular biology hardware

- DNA field-effect transistor

- DNA sequencing theory – Biological theory

- DNA sequencer – Scientific instrument that automates the DNA sequencing process

- Genographic Project – Citizen science project

- Genome project – Scientific endeavours to determine the complete genome sequence of an organism

- Genome sequencing of endangered species – DNA testing for endangerment assessment

- Genome skimming – Method of genome sequencing

- IsoBase – Database for identifying functionally related proteins

- Linked-read sequencing

- Jumping library

- Nucleic acid sequence – Succession of nucleotides in a nucleic acid

- Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification

- Personalized medicine – Medical model that tailors medical practices to the individual patient

- Protein sequencing – Sequencing of amino acid arrangement in a protein

- Sequence mining – Data mining technique

- Sequence profiling tool

- Sequencing by hybridization

- Sequencing by ligation

- TIARA (database) – Database of personal genomics information

- Transmission electron microscopy DNA sequencing – Single-molecule sequencing technology

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Next-generation" remains in broad use as of 2019. For instance, Straiton J, Free T, Sawyer A, Martin J (February 2019). "From Sanger Sequencing to Genome Databases and Beyond". BioTechniques. 66 (2): 60–63. doi:10.2144/btn-2019-0011. PMID 30744413.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized genomic research. (opening sentence of the article)

References

[edit]- ^ "Introducing 'dark DNA' – the phenomenon that could change how we think about evolution". 24 August 2017.

- ^ Behjati S, Tarpey PS (December 2013). "What is next generation sequencing?". Archives of Disease in Childhood: Education and Practice Edition. 98 (6): 236–8. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-304340. PMC 3841808. PMID 23986538.

- ^ Chmielecki J, Meyerson M (14 January 2014). "DNA sequencing of cancer: what have we learned?". Annual Review of Medicine. 65 (1): 63–79. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-060712-200152. PMID 24274178.

- ^ a b c d Abate AR, Hung T, Sperling RA, Mary P, Rotem A, Agresti JJ, et al. (December 2013). "DNA sequence analysis with droplet-based microfluidics". Lab on a Chip. 13 (24): 4864–9. doi:10.1039/c3lc50905b. PMC 4090915. PMID 24185402.

- ^ Pekin D, Skhiri Y, Baret JC, Le Corre D, Mazutis L, Salem CB, et al. (July 2011). "Quantitative and sensitive detection of rare mutations using droplet-based microfluidics". Lab on a Chip. 11 (13): 2156–66. doi:10.1039/c1lc20128j. PMID 21594292.

- ^ Olsvik O, Wahlberg J, Petterson B, Uhlén M, Popovic T, Wachsmuth IK, Fields PI (January 1993). "Use of automated sequencing of polymerase chain reaction-generated amplicons to identify three types of cholera toxin subunit B in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains". J. Clin. Microbiol. 31 (1): 22–25. doi:10.1128/JCM.31.1.22-25.1993. PMC 262614. PMID 7678018.

- ^ Pettersson E, Lundeberg J, Ahmadian A (February 2009). "Generations of sequencing technologies". Genomics. 93 (2): 105–11. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.10.003. PMID 18992322.

- ^ a b c Jay E, Bambara R, Padmanabhan R, Wu R (March 1974). "DNA sequence analysis: a general, simple and rapid method for sequencing large oligodeoxyribonucleotide fragments by mapping". Nucleic Acids Research. 1 (3): 331–53. doi:10.1093/nar/1.3.331. PMC 344020. PMID 10793670.

- ^ Hunt, Katie (17 February 2021). "World's oldest DNA sequenced from a mammoth that lived more than a million years ago". CNN. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (17 February 2021). "Million-year-old mammoth genomes shatter record for oldest ancient DNA – Permafrost-preserved teeth, up to 1.6 million years old, identify a new kind of mammoth in Siberia" (PDF). Nature. 590 (7847): 537–538. Bibcode:2021Natur.590..537C. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-00436-x. PMID 33597786. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Castro, Christina; Marine, Rachel; Ramos, Edward; Ng, Terry Fei Fan (2019). "The effect of variant interference on de novo assembly for viral deep sequencing". BMC Genomics. 21 (1): 421. bioRxiv 10.1101/815480. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-06801-w. PMC 7306937. PMID 32571214.

- ^ a b Wohl, Shirlee; Schaffner, Stephen F.; Sabeti, Pardis C. (2016). "Genomic Analysis of Viral Outbreaks". Annual Review of Virology. 3 (1): 173–195. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-035747. PMC 5210220. PMID 27501264.

- ^ Boycott, Kym M.; Vanstone, Megan R.; Bulman, Dennis E.; MacKenzie, Alex E. (October 2013). "Rare-disease genetics in the era of next-generation sequencing: discovery to translation". Nature Reviews Genetics. 14 (10): 681–691. doi:10.1038/nrg3555. PMID 23999272. S2CID 8496181.

- ^ Bean, Lora; Funke, Birgit; Carlston, Colleen M.; Gannon, Jennifer L.; Kantarci, Sibel; Krock, Bryan L.; Zhang, Shulin; Bayrak-Toydemir, Pinar (March 2020). "Diagnostic gene sequencing panels: from design to report—a technical standard of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)". Genetics in Medicine. 22 (3): 453–461. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0666-z. ISSN 1098-3600. PMID 31732716.

- ^ Schleusener V, Köser CU, Beckert P, Niemann S, Feuerriegel S (2017). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistance prediction and lineage classification from genome sequencing: comparison of automated analysis tools". Sci Rep. 7 46327. Bibcode:2017NatSR...746327S. doi:10.1038/srep46327. PMC 7365310. PMID 28425484.

- ^ Mahé P, El Azami M, Barlas P, Tournoud M (2019). "A large scale evaluation of TBProfiler and Mykrobe for antibiotic resistance prediction in Mycobacterium tuberculosis". PeerJ. 7 e6857. doi:10.7717/peerj.6857. PMC 6500375. PMID 31106066.

- ^ Mykrobe predictor –Antibiotic resistance prediction for S. aureus and M. tuberculosis from whole genome sequence data

- ^ Bradley, Phelim; Gordon, N. Claire; Walker, Timothy M.; Dunn, Laura; Heys, Simon; Huang, Bill; Earle, Sarah; Pankhurst, Louise J.; Anson, Luke; de Cesare, Mariateresa; Piazza, Paolo; Votintseva, Antonina A.; Golubchik, Tanya; Wilson, Daniel J.; Wyllie, David H.; Diel, Roland; Niemann, Stefan; Feuerriegel, Silke; Kohl, Thomas A.; Ismail, Nazir; Omar, Shaheed V.; Smith, E. Grace; Buck, David; McVean, Gil; Walker, A. Sarah; Peto, Tim E. A.; Crook, Derrick W.; Iqbal, Zamin (21 December 2015). "Rapid antibiotic-resistance predictions from genome sequence data for Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis". Nature Communications. 6 (1) 10063. Bibcode:2015NatCo...610063B. doi:10.1038/ncomms10063. PMC 4703848. PMID 26686880.

- ^ "Michael Mosley vs the superbugs". Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Mykrobe, Mykrobe-tools, 24 December 2022, retrieved 2 January 2023

- ^ Curtis C, Hereward J (29 August 2017). "From the crime scene to the courtroom: the journey of a DNA sample". The Conversation.

- ^ Moréra S, Larivière L, Kurzeck J, Aschke-Sonnenborn U, Freemont PS, Janin J, Rüger W (August 2001). "High resolution crystal structures of T4 phage beta-glucosyltransferase: induced fit and effect of substrate and metal binding". Journal of Molecular Biology. 311 (3): 569–77. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.4905. PMID 11493010.

- ^ Ehrlich M, Gama-Sosa MA, Huang LH, Midgett RM, Kuo KC, McCune RA, Gehrke C (April 1982). "Amount and distribution of 5-methylcytosine in human DNA from different types of tissues of cells". Nucleic Acids Research. 10 (8): 2709–21. doi:10.1093/nar/10.8.2709. PMC 320645. PMID 7079182.

- ^ Ehrlich M, Wang RY (June 1981). "5-Methylcytosine in eukaryotic DNA". Science. 212 (4501): 1350–7. Bibcode:1981Sci...212.1350E. doi:10.1126/science.6262918. PMID 6262918.

- ^ Song CX, Clark TA, Lu XY, Kislyuk A, Dai Q, Turner SW, et al. (November 2011). "Sensitive and specific single-molecule sequencing of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine". Nature Methods. 9 (1): 75–7. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1779. PMC 3646335. PMID 22101853.

- ^ Czernecki, Dariusz; Bonhomme, Frédéric; Kaminski, Pierre-Alexandre; Delarue, Marc (5 August 2021). "Characterization of a triad of genes in cyanophage S-2L sufficient to replace adenine by 2-aminoadenine in bacterial DNA". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 4710. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.4710C. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25064-x. PMC 8342488. PMID 34354070. S2CID 233745192.

- ^ "Direct detection and sequencing of damaged DNA bases". PacBio. Retrieved 31 July 2024.

- ^ Watson JD, Crick FH (1953). "The structure of DNA". Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 18: 123–31. doi:10.1101/SQB.1953.018.01.020. PMID 13168976.

- ^ Marks, L. "The path to DNA sequencing: The life and work of Frederick Sanger". What is Biotechnology?. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Min Jou W, Haegeman G, Ysebaert M, Fiers W (May 1972). "Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein". Nature. 237 (5350): 82–8. Bibcode:1972Natur.237...82J. doi:10.1038/237082a0. PMID 4555447. S2CID 4153893.

- ^ Fiers W, Contreras R, Duerinck F, Haegeman G, Iserentant D, Merregaert J, Min Jou W, Molemans F, Raeymaekers A, Van den Berghe A, Volckaert G, Ysebaert M (April 1976). "Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene". Nature. 260 (5551): 500–7. Bibcode:1976Natur.260..500F. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203. S2CID 4289674.

- ^ Ozsolak F, Milos PM (February 2011). "RNA sequencing: advances, challenges and opportunities". Nature Reviews Genetics. 12 (2): 87–98. doi:10.1038/nrg2934. PMC 3031867. PMID 21191423.

- ^ "Ray Wu Faculty Profile". Cornell University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009.

- ^ Padmanabhan R, Jay E, Wu R (June 1974). "Chemical synthesis of a primer and its use in the sequence analysis of the lysozyme gene of bacteriophage T4". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (6): 2510–4. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.2510P. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.6.2510. PMC 388489. PMID 4526223.

- ^ Onaga LA (June 2014). "Ray Wu as Fifth Business: Demonstrating Collective Memory in the History of DNA Sequencing". Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science. Part C. 46: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2013.12.006. PMID 24565976.

- ^ Wu R (1972). "Nucleotide sequence analysis of DNA". Nature New Biology. 236 (68): 198–200. doi:10.1038/newbio236198a0. PMID 4553110.

- ^ Padmanabhan R, Wu R (1972). "Nucleotide sequence analysis of DNA. IX. Use of oligonucleotides of defined sequence as primers in DNA sequence analysis". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 48 (5): 1295–302. Bibcode:1972BBRC...48.1295P. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(72)90852-2. PMID 4560009.

- ^ Wu R, Tu CD, Padmanabhan R (1973). "Nucleotide sequence analysis of DNA. XII. The chemical synthesis and sequence analysis of a dodecadeoxynucleotide which binds to the endolysin gene of bacteriophage lambda". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 55 (4): 1092–99. Bibcode:1973BBRC...55.1092R. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(73)80007-5. PMID 4358929.

- ^ a b c Maxam AM, Gilbert W (February 1977). "A new method for sequencing DNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74 (2): 560–64. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74..560M. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.2.560. PMC 392330. PMID 265521.

- ^ Gilbert, W. DNA sequencing and gene structure. Nobel lecture, 8 December 1980.

- ^ Gilbert W, Maxam A (December 1973). "The Nucleotide Sequence of the lac Operator". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 70 (12): 3581–84. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.3581G. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.12.3581. PMC 427284. PMID 4587255.

- ^ "Chapter 5: Investigating DNA". Chemistry. Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ Sanger, F.; Coulson, A. R. (25 May 1975). "A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase". Journal of Molecular Biology. 94 (3): 441–448. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(75)90213-2. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 1100841.

- ^ Cook-Deegan, Robert (1995). The gene wars: science, politics, and the human genome (1. publ. as a Norton paperback ed.). New York NY: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31399-4.

- ^ Johnson, Carolyn Y. (12 March 2015). "A physicist, biologist, Nobel laureate, CEO, and now, artist". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ a b c Heather, James M.; Chain, Benjamin (January 2016). "The sequence of sequencers: The history of sequencing DNA". Genomics. 107 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2015.11.003. PMC 4727787. PMID 26554401.

- ^ Deharvengt, Sophie J.; Petersen, Lauren M.; Jung, Hou-Sung; Tsongalis, Gregory J. (2020). "Nucleic acid analysis in the clinical laboratory". Contemporary Practice in Clinical Chemistry. pp. 215–234. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-815499-1.00013-2. ISBN 978-0-12-815499-1.

- ^ Elsayed, Fadwa A.; Grolleman, Judith E.; Ragunathan, Abiramy; Buchanan, Daniel D.; van Wezel, Tom; de Voer, Richarda M.; Boot, Arnoud; Stojovska, Marija Staninova; Mahmood, Khalid; Clendenning, Mark; de Miranda, Noel; Dymerska, Dagmara; Egmond, Demi van; Gallinger, Steven; Georgeson, Peter; Hoogerbrugge, Nicoline; Hopper, John L.; Jansen, Erik A.M.; Jenkins, Mark A.; Joo, Jihoon E.; Kuiper, Roland P.; Ligtenberg, Marjolijn J.L.; Lubinski, Jan; Macrae, Finlay A.; Morreau, Hans; Newcomb, Polly; Nielsen, Maartje; Palles, Claire; Park, Daniel J.; Pope, Bernard J.; Rosty, Christophe; Ruiz Ponte, Clara; Schackert, Hans K.; Sijmons, Rolf H.; Tomlinson, Ian P.; Tops, Carli M.J.; Vreede, Lilian; Walker, Romy; Win, Aung K. (December 2020). "Monoallelic NTHL1 Loss-of-Function Variants and Risk of Polyposis and Colorectal Cancer". Gastroenterology. 159 (6): 2241–2243.e6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.042. hdl:2066/228713. PMC 7899696. PMID 32860789.

- ^ a b Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR (December 1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74 (12): 5463–77. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5463S. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC 431765. PMID 271968.

- ^ Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG, Brown NL, Coulson AR, Fiddes CA, Hutchison CA, Slocombe PM, Smith M (February 1977). "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA". Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828. S2CID 4206886.

- ^ Marks, L. "The next frontier: Human viruses". What is Biotechnology?. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Beck S, Pohl FM (1984). "DNA sequencing with direct blotting electrophoresis". EMBO J. 3 (12): 2905–09. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02230.x. PMC 557787. PMID 6396083.

- ^ United States Patent 4,631,122 (1986)

- ^ Feldmann H, et al. (1994). "Complete DNA sequence of yeast chromosome II". EMBO J. 13 (24): 5795–809. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06923.x. PMC 395553. PMID 7813418.

- ^ Smith LM, Sanders JZ, Kaiser RJ, Hughes P, Dodd C, Connell CR, Heiner C, Kent SB, Hood LE (12 June 1986). "Fluorescence Detection in Automated DNA Sequence Analysis". Nature. 321 (6071): 674–79. Bibcode:1986Natur.321..674S. doi:10.1038/321674a0. PMID 3713851. S2CID 27800972.

- ^ Prober JM, Trainor GL, Dam RJ, Hobbs FW, Robertson CW, Zagursky RJ, Cocuzza AJ, Jensen MA, Baumeister K (16 October 1987). "A system for rapid DNA sequencing with fluorescent chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides". Science. 238 (4825): 336–41. Bibcode:1987Sci...238..336P. doi:10.1126/science.2443975. PMID 2443975.

- ^ Adams MD, Kelley JM, Gocayne JD, Dubnick M, Polymeropoulos MH, Xiao H, Merril CR, Wu A, Olde B, Moreno RF (June 1991). "Complementary DNA sequencing: expressed sequence tags and human genome project". Science. 252 (5013): 1651–56. Bibcode:1991Sci...252.1651A. doi:10.1126/science.2047873. PMID 2047873. S2CID 13436211.

- ^ Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, Clayton RA, Kirkness EF, Kerlavage AR, Bult CJ, Tomb JF, Dougherty BA, Merrick JM (July 1995). "Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd". Science. 269 (5223): 496–512. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..496F. doi:10.1126/science.7542800. PMID 7542800.

- ^ Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, et al. (February 2001). "Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome" (PDF). Nature. 409 (6822): 860–921. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..860L. doi:10.1038/35057062. PMID 11237011.

- ^ Venter JC, Adams MD, et al. (February 2001). "The sequence of the human genome". Science. 291 (5507): 1304–51. Bibcode:2001Sci...291.1304V. doi:10.1126/science.1058040. PMID 11181995.

- ^ "First complete sequence of a human genome". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 11 April 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ "First complete sequence of a human genome". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 11 April 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ Hartley, Gabrielle (31 March 2022). "The Human Genome Project pieced together only 92% of the DNA – now scientists have finally filled in the remaining 8%". The Conversation. Retrieved 6 February 2025.

- ^ Yang, Aimin; Zhang, Wei; Wang, Jiahao; Yang, Ke; Han, Yang; Zhang, Limin (2020). "Review on the Application of Machine Learning Algorithms in the Sequence Data Mining of DNA". Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 8 1032. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2020.01032. PMC 7498545. PMID 33015010.

- ^ Lyman DF, Bell A, Black A, Dingerdissen H, Cauley E, Gogate N, Liu D, Joseph A, Kahsay R, Crichton DJ, Mehta A, Mazumder R (19 September 2022). "Modeling and integration of N-glycan biomarkers in a comprehensive biomarker data model". Glycobiology. 32 (10): 855–870. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwac046. PMC 9487899. PMID 35925813. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Espacenet – Bibliographic data". worldwide.espacenet.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ Ronaghi M, Karamohamed S, Pettersson B, Uhlén M, Nyrén P (1996). "Real-time DNA sequencing using detection of pyrophosphate release". Analytical Biochemistry. 242 (1): 84–89. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0432. PMID 8923969.

- ^ a b Kawashima, Eric H.; Laurent Farinelli; Pascal Mayer (12 May 2005). "Patent: Method of nucleic acid amplification". Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ^ Ewing B, Green P (March 1998). "Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities". Genome Res. 8 (3): 186–94. doi:10.1101/gr.8.3.186. PMID 9521922.

- ^ "Quality Scores for Next-Generation Sequencing" (PDF). Illumina. 31 October 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ a b Brenner S, Johnson M, Bridgham J, Golda G, Lloyd DH, Johnson D, Luo S, McCurdy S, Foy M, Ewan M, Roth R, George D, Eletr S, Albrecht G, Vermaas E, Williams SR, Moon K, Burcham T, Pallas M, DuBridge RB, Kirchner J, Fearon K, Mao J, Corcoran K (2000). "Gene expression analysis by massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) on microbead arrays". Nature Biotechnology. 18 (6): 630–34. doi:10.1038/76469. PMID 10835600. S2CID 13884154.

- ^ "maxam gilbert sequencing". PubMed.

- ^ Sanger F, Coulson AR (May 1975). "A rapid method for determining sequences in DNA by primed synthesis with DNA polymerase". J. Mol. Biol. 94 (3): 441–48. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(75)90213-2. PMID 1100841.

- ^ Wetterstrand, Kris. "DNA Sequencing Costs: Data from the NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP)". National Human Genome Research Institute. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ Nyren, P.; Pettersson, B.; Uhlen, M. (January 1993). "Solid Phase DNA Minisequencing by an Enzymatic Luminometric Inorganic Pyrophosphate Detection Assay". Analytical Biochemistry. 208 (1): 171–175. doi:10.1006/abio.1993.1024. PMID 8382019.