Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Poor relief

View on Wikipedia

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty, particularly before the Liberal welfare reforms beginning in 1906. Beginning in 1551, the Parliaments of England and of Great Britain and the United Kingdom made legal provision for government and ecclesiastical funds to be used to alleviate extreme poverty. The Poor Relief Act 1601 established the system that would operate without major changes until the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which reorganized the system, aiming to curb abuses and cut overall spending on relief.

Beginning in the late 19th century, changing attitudes to poverty and the widening of the franchise to include at first some and then all working-class people through a series of Representation of the People Acts led to the development of the first predecessors of the modern welfare state. Between 1906 and 1914, the Liberal Party created a suite of basic welfare programs that reduced dependence on the Poor Law system but did not abolish it. The vestiges of the system remained until 1948 with the passage of the Attlee ministry’s National Assistance Act, which transferred non-National Insurance poor relief efforts to the new National Assistance programme. Today, Income Support provides financial resources for those with little or no income.

Tudor era

[edit]

In the late 15th century, Parliament took action on the growing[citation needed] problem of poverty, focusing on punishing people for being "vagabonds" and for begging. In 1495, during the reign of King Henry VII, Parliament enacted the Vagabonds and Beggars Act 1494. This provided for officers of the law to arrest and hold "all such vagabonds, idle and suspect persons living suspiciously and them so taken to set in stocks, there to remain three nights and to have none other sustenance but bread and water; and after the said three days and three nights, to be had out and set at large and to be commanded to avoid the town."[1] As historian Mark Rathbone has discussed in his article "Vagabond!",[1] this act of Parliament relied on a very loose definition of a vagabond and did not make any distinction between those who were simply unemployed and looking for employment and those who chose to live the life of a vagabond. In addition, the act failed to recognise the impotent poor; those who could not provide for themselves. These included the sick, the elderly, and the disabled. This lack of a precise definition of a vagabond would hinder the effectiveness of the Vagabonds and Beggars Act 1494 for years to come.

Dissolution of the Monasteries

[edit]

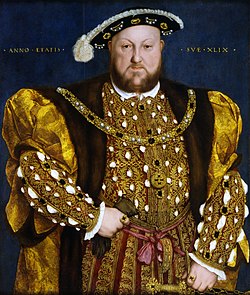

The problem of poverty in England was exacerbated during the early 16th century by a dramatic increase in the population. This rose "from little more than 2 million in 1485, ... [to] about 2.8 million by the end of Henry VII's reign (1509)". The population was growing faster than the economy's ability to provide employment opportunities.[1] The problem was made worse because during the English Reformation, Henry VIII severed the ecclesiastical governance of his kingdoms of England and Ireland and made himself the Supreme Head of the Church of England. This involved the Dissolution of the Monasteries in England and Wales: the assets of hundreds of rich religious institutions, including their great estates, were taken by the Crown. This had a devastating impact on poor relief. According to the historian Paul Slack, prior to the Dissolution "it has been estimated that monasteries alone provided 6,500 pounds a year in alms before 1537 [equivalent to £4,700,000 in 2023[2]]; and that sum was not made good by private benefactions until after 1580."[3] In addition to the closing of the monasteries, most hospitals (which in the 16th century were generally almshouses rather than medical institutions) were also closed, as they "had come to be seen as special types of religious houses".[4] This left many of the elderly and sick without accommodation or care.

Vagabonds Acts

[edit]

In 1531, the Vagabonds and Beggars Act 1494 was revised, and a new act, the Vagabonds Act 1530, was passed by Parliament which did make some provision for the different classes of the poor. The sick, the elderly, and the disabled were to be issued with licences to beg. But those who were out of work and in search of employment were still not spared punishment. Throughout the 16th century, a fear of social unrest was the primary motive for much legislation that was passed by Parliament. This fear of social unrest carried into the reign of Edward VI. A new level of punishment was introduced in the Duke of Somerset's Vagabonds Act 1547.[5] "Two years' servitude and branding with a 'V' was the penalty for the first offense, and attempts to run away were to be punished by lifelong slavery and, there for a second time, execution."[1] However, "there is no evidence that the Act was enforced."[1] In 1550 these punishments were revised in a new act that was passed. The Vagabonds Act 1549 makes a reference to the limited enforcement of the punishments established by the Vagabonds Act 1547 by stating "the extremity of some [of the laws] have been occasion that they have not been put into use."[1]

Parliament and the parish

[edit]Following the revision of the Vagabonds Act 1547, Parliament passed the Poor Act 1551. This focused on using the parishes as a source of funds to combat the increasing poverty epidemic. This statute appointed two "overseers" from each parish to collect money to be distributed to the poor who were considered to belong to the parish. These overseers were to 'gently ask' for donations for poor relief; refusal would ultimately result in a meeting with the local bishop, who would 'induce and persuade' the recalcitrant parishioners.[1] However, at times even such a meeting with the bishop would often fail to achieve its object.

Sensing that voluntary donation was ineffective, Parliament passed new legislation, the Poor Act 1562, in 1563, and once this act took effect parishioners could be brought by the bishop before the justices, and continued refusal could lead to imprisonment until contribution was made.[1] However, even the Poor Act 1562 still suffered from shortcomings, because individuals could decide for themselves how much money to give in order to gain their freedom.

A more structured system of donations was established by the Vagabonds Act 1572. After determining the amount of funds needed to provide for the poor of each parish, justices of the peace were granted the authority to determine the amount of the donation from each parish's more wealthy property-owners. This act finally turned these donations into what was effectively a local tax.[6]

In addition to creating these new imposed taxes, the Vagabonds Act 1572 created a new set of punishments to inflict upon the population of vagabonds. These included being "bored through the ear" for a first offense and hanging for "persistent beggars".[1] Unlike the previous brutal punishments established by the Vagabonds Act 1547, these extreme measures were enforced with great frequency.

However, despite its introduction of such violent actions to deter vagabonding, the Vagabonds Act 1572 was the first time that Parliament had passed legislation which began to distinguish between different categories of vagabonds. "Peddlers, tinkers, workmen on strike, fortune tellers, and minstrels" were not spared these gruesome acts of deterrence. This law punished all able bodied men "without land or master" who would neither accept employment nor explain the source of their livelihood.[1] In this newly established definition of what constituted a vagabond, men who had been discharged from the military, released servants, and servants whose masters had died were specifically exempted from the act's punishments. This legislation did not establish any means to support these individuals.

A new approach

[edit]A system to support individuals who were willing to work, but who were having difficulty in finding employment, was established by the Poor Act 1575. As provided for in this, justices of the peace were authorized to provide any town which needed it with a stock of flax, hemp, or other materials on which paupers could be employed and to erect a "house of correction" in every county for the punishment of those who refused work.[6] This was the first time Parliament had attempted to provide labour to individuals as a means to combat the increasing numbers of "vagabonds".

Two years after the Poor Act 1575 was passed into law, yet more dramatic changes were made to the methods to fight vagabondage and to provide relief to the poor. The Act of 1578[clarification needed] transferred power from the justices of the peace to church officials in the area of collecting the new taxes for the relief of poverty established in the Vagabonds Act 1572. In addition, this Act of 1578[clarification needed] also extended the power of the church by stating that "vagrants were to be summarily whipped and returned to their place of settlement by parish constables."[1] By eliminating the need for the involvement of the Justices, law enforcement was streamlined.

End of the Elizabethan Era to 1750

[edit]

Starting as early as 1590, public authorities began to take a more selective approach to supporting the poor. Those who were considered to be legitimately needy, sometimes called the "deserving poor" or "worthy poor", were allowed assistance, while those who were idle were not. People incapable of providing for themselves, such as young orphans, the elderly, and the mentally and physically handicapped, were seen to be deserving, whereas those who were physically able but were too lazy to work were considered as "idle" and were seen as of bad moral character, and thus undeserving of help.[7] Most poor relief in the 17th century came from voluntary charity which mostly was in the form of food and clothing. Parishes distributed land and animals. Institutionalized charities offered loans to help craftsmen to alms houses and hospitals.[8]

The Poor Relief Act 1597 provided the first complete code of poor relief, established overseers of the poor and was later amended by the Poor Relief Act 1601, which was one of the longest-lasting achievements of her reign, left unaltered until 1834. This law made each parish responsible for supporting the legitimately needy in their community.[6] It taxed wealthier citizens of the country to provide basic shelter, food and clothing, though they were not obligated to provide for those outside of their community.

Parishes responsible for their own community caused problems because some were more generous than others. This caused the poor to migrate to other parishes that were not their own. In order to counteract this problem, the Poor Relief Act 1662, also known as the Settlement Act, was implemented. This created many sojourners, people who resided in different settlements that were not their legal one.[8] The Settlement Act allowed such people to be forcefully removed, and garnered a negative reaction from the population. In order to fix the flaws of the 1662 act, the Poor Relief Act 1691 came into effect such that it presented methods by which people could gain settlement in new locations. Such methods included "owning or renting property above a certain value or paying parish rates, but also by completing a legal apprenticeship or a one-year service while unmarried, or by serving a public office" for that identical length of time.[8]

The main points of this system were the following:

- The impotent poor (people who could not work) were to be cared for in an almshouse or a poorhouse. In this way, the law offered relief to people who were unable to work, mainly those who were elderly, blind, or crippled or otherwise physically infirm.[citation needed]

- The able-bodied poor were to be set to work in a House of Industry. All materials necessary for this work were to be provided for them.[9]

- The idle poor (those considered lazy and not making an effort to find work) and vagrants were to be sent to a House of Correction or prison.[citation needed]

- Pauper children would become apprentices.[citation needed]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the population of England nearly doubled.[7] Capitalism in the agricultural and manufacturing arenas started to emerge, and trade abroad significantly increased. Despite this flourishing of expansion, sufficient employment rates had yet to be attained by the late 1600s. The population increased at alarming rates, outpacing the increase in productivity, which resulted inevitably in inflation.[6] Concurrently, wages decreased, declining to a point roughly half that of average wages of a century before.

"The boom-and-bust nature of European trade in woolen cloth, England's major manufacture and export" caused a larger fraction of the population of England to fall under poverty. With this increase in poverty, all charities operated by the Catholic Church were abolished due to the impact of protestant reformation.[6]

Workhouse Test Act

[edit]A law passed by the Parliament of Great Britain and sponsored by Sir Edward Knatchbull in 1723 introduced a "workhouse test", which meant that a person who wanted to receive poor relief had to enter a workhouse and undertake a set amount of work. The test was intended to prevent irresponsible claims on a parish's poor rate.

The Industrial Revolution

[edit]Child labour

[edit]

By the mid to late 18th century most of the British Isles was involved in the process of industrialization in terms of production of goods, manner of markets[clarification needed] and concepts of economic class. In some cases, factory owners "employed" children without paying them, thus exacerbating poverty levels.[10] Furthermore, the Poor Laws of this era encouraged children to work through an apprenticeship, but by the end of the 18th century the situation changed as masters became less willing to apprentice children, and factory owners then set about employing them to keep wages down.[10] This meant that there were not many jobs for adult labourers.[10] For those who could not find work there was the workhouse as a means of sustenance.

Gilbert's Act

[edit]The 1782 poor relief law proposed by Thomas Gilbert aimed to organise poor relief on a county basis, counties being organised into parishes which could set up workhouses between them. However, these workhouses were intended to help only the elderly, sick and orphaned, not the able-bodied poor. The sick, elderly and infirm were cared for in poorhouses whereas the able-bodied poor were provided with poor relief in their own homes.

Speenhamland system

[edit]The Speenhamland system was a form of outdoor relief intended to mitigate rural poverty at the end of the 18th century and during the early 19th century. The system was named after a 1795 meeting at the Pelican Inn in Speenhamland, Berkshire, where a number of local magistrates devised the system as a means to alleviate the distress caused by high grain prices. The increase in the price of grain most probably occurred as a result of a poor harvest in the years 1795–96, though at the time this was subject to great debate. Many blamed middlemen and hoarders as the ultimate architects of the shortage.

The authorities at Speenhamland approved a means-tested sliding scale of wage supplements in order to mitigate the worst effects of rural poverty. Families were paid extra to top up wages to a set level according to a table. This level varied according to the number of children and the price of bread.

In 1834, the Report of the Royal Commission into the Operation of the Poor Laws 1832 called the Speenhamland System a "universal system of pauperism". The system allowed employers, including farmers and the nascent industrialists of the town, to pay below subsistence wages, because the parish would make up the difference and keep their workers alive. So the workers' low income was unchanged and the poor rate contributors subsidised the farmers.[11]

New Poor Law of 1834

[edit]Indoor relief versus outdoor relief

[edit]

Following the onset of the Industrial Revolution, in 1834 the Parliament of the United Kingdom revised the Poor Relief Act 1601 after studying the conditions found in 1832. Over the next decade they began phasing out outdoor relief and pushing the paupers towards indoor relief. The differences between the two was that outdoor relief was a monetary contribution to the needy, whereas indoor relief meant the individual was sent to one of the workhouses.

The Great Famine (Ireland)

[edit]This article needs attention from an expert in history. The specific problem is: citation needed. (October 2019) |

Following the reformation of the Poor Laws in 1834, Ireland experienced a severe potato blight that lasted from 1845 to 1849 and killed an estimated 1.5 million people. The effects of the famine lasted until 1851. During this period the people of Ireland lost much land and many jobs, and appealed to the Westminster Parliament for aid.[citation needed] This aid generally came in the form of establishing more workhouses as indoor relief.[12] Some people[who?] argue that as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was in its prime as an empire, it could have given more aid in the form of money, food or rent subsidies.[citation needed]

In other parts of the United Kingdom, amendments to and adoptions of poor laws came in and around the same time. In Scotland, for example, the Poor Law (Scotland) Act 1845 revised the Poor Laws that were implemented under the 1601 Acts.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rathbone, Mark (2005). "Vagabond!". History Review. History Today: 8–13.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Slack, Paul (1988). Poverty and Policy in Tudor and Stuart England. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-48965-2.

- ^ Rushton, N. S.; Sigle-Rushton, W. (2001). "Monastic Poor Relief in Sixteenth-Century England". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 32 (2): 193–216. doi:10.1162/002219501750442378. PMID 19035026. S2CID 7272220.

- ^ Williams, Penry (1998): The Later Tudors: England 1547–1603. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-288044-6. p. 48

- ^ a b c d e Slack, Paul. 1984. "Poverty in Elizabethan England". History Today 34, no. 10: 5. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed 1 August 2010).

- ^ a b McIntosh, M. K. (2005). "Poverty, Charity, and Coercion in Elizabethan England". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 35 (3): 457–479. doi:10.1162/0022195052564234. S2CID 144864528.

- ^ a b c Anne Winter. 2008. "Caught between Law and Practice: Migrants and Settlement Legislation in the Southern Low Countries in a Comparative Perspective, c. 1700–1900". Rural History 19, no. 2: 137–162. Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed August 1, 2010).

- ^ "British social policy, 1601-1948". An introduction to Social Policy. Robert Gordon University. Archived from the original on 20 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Honeyman, K. (2007). "The Poor Law, the Parish Apprentice, and the Textile Industries in the North of England, 1780–1830". Northern History. 44 (2): 115–140. doi:10.1179/174587007X208263. S2CID 159489267.

- ^ Milton D. Speizman, "Speenhamland: an experiment in guaranteed income." Social Service Review 40.1 (1966): 44-55.

- ^ Thomas E. Hachey, Joseph M. Hermon, Jr. and Lawrence J McCaffery. The Irish Experience: A Concise History; (New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1996) 92–93 [ISBN missing]

Poor relief

View on GrokipediaPoor relief refers to the organized provision of assistance to the destitute, encompassing public and charitable measures funded primarily through local taxes to alleviate immediate needs and prevent vagrancy.[1] In England, this crystallized into a compulsory parish-based system under the Poor Law of 1601, which required overseers to collect rates from ratepayers for relieving the elderly, widows, children, sick, disabled, and unemployed via outdoor relief or institutional care.[1][2] The framework categorized recipients as "deserving" poor warranting aid without stigma and "undeserving" able-bodied paupers subject to work tests, with settlement laws restricting relief to parishioners to curb migration.[2] By the 18th century, escalating costs from demographic pressures and economic shifts prompted reforms, culminating in the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, which centralized administration through unions and workhouses enforcing the "less eligibility" principle—conditions harsher than the lowest-paid labor—to deter idleness and reduce expenditure.[1][3] While sustaining vulnerable populations and averting famine, the system faced critique for subsidizing population growth, distorting labor markets, and engendering dependency, influencing debates on welfare's incentives and sustainability.[1]

Pre-Tudor Origins

Medieval Ecclesiastical Charity

In medieval Europe from the 12th to 15th centuries, the Christian Church served as the primary institution for alleviating poverty through voluntary acts of charity, rooted in biblical mandates such as Matthew 25:35-40, which emphasized feeding the hungry and sheltering the stranger as pathways to spiritual merit.[4] Monasteries, following the Benedictine Rule established in the 6th century but widely practiced by the 12th, allocated portions of their daily produce—typically one-tenth to one-third—for alms distribution to the needy at their gates, providing food, clothing, and occasional shelter without compulsion or taxation.[5] Parish priests similarly dispensed alms from church collections and tithes, while mendicant friars, such as the Franciscans founded in 1209 and Dominicans in 1216, actively begged and redistributed resources to the destitute, embodying evangelical poverty as a model for lay Christians.[6] Ecclesiastical charity distinguished between the "deserving" poor—those deemed impotent, including the elderly, infirm, widows, and orphans, whose condition was often viewed theologically as a test of faith or divine providence—and the "undeserving," comprising able-bodied vagrants whose idleness was interpreted as moral failing or sin, warranting less support or correction rather than indulgence.[7] This categorization, formalized in 12th-century canon law by decretists interpreting Gratian's Decretum (circa 1140), prioritized aid to those unable to work, reflecting a causal understanding that true poverty stemmed from unavoidable misfortune rather than vice, though friars occasionally extended aid indiscriminately to fulfill the corporal works of mercy.[5] Theological treatises, including those by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century, reinforced almsgiving as a virtue that remitted sins and gained heavenly reward, but cautioned against enabling sloth among the sturdy beggar.[8] Support mechanisms included almshouses and hospitals, with over 750 such institutions recorded in England by 1300, many founded by bishops or monastic orders for the sick and poor, funded solely through endowments, bequests, and pious donations rather than systematic levies.[9] Craft and religious guilds, voluntary associations emerging in the 12th century, supplemented ecclesiastical efforts by pooling member contributions for mutual aid and charitable distributions to non-members in need, such as during famines, without state oversight or mandatory contributions.[10] This decentralized, faith-driven system, while pervasive, remained ad hoc and insufficient for widespread destitution, as evidenced by recurring pleas for charity at church doors and the absence of comprehensive records indicating universal coverage.[11]Post-Black Death Legislation

The Black Death of 1348–1349 decimated England's population, with estimates indicating a decline from approximately 4 to 6 million to 2 to 3 million, representing a mortality rate of 40 to 60 percent.[12] This demographic catastrophe created acute labor shortages, enabling surviving workers to demand higher wages and greater mobility, which disrupted traditional feudal obligations and prompted landowners to seek legislative intervention to restore pre-plague labor conditions.[12] Rather than establishing relief mechanisms, early statutes prioritized wage suppression and coerced employment to counteract workers' bargaining power, marking the inception of state efforts to manage poverty through punitive controls on vagrancy and idleness.[13] The Ordinance of Labourers, issued on 18 June 1349, and the subsequent Statute of Labourers of 1351 directly addressed these pressures by capping wages and prices at pre-plague levels, prohibiting employers from offering or workers from demanding higher rates under penalty of fines or imprisonment.[14] These laws mandated that all able-bodied persons under 60 years old—excluding those with independent means or formal exemptions—accept available work at the fixed rates, with refusal treated as vagrancy punishable by arrest and forced labor.[15] Provisions also barred the enticement of another's servants or laborers without consent, aiming to immobilize the workforce and prevent migration to higher-paying regions, while restricting begging to the genuinely infirm and localizing responsibility for their support to prevent influxes of outsiders.[14] Enforcement relied on local justices of the peace, though widespread evasion and judicial inconsistencies limited efficacy, as market forces continued to drive wages upward.[13] Subsequent measures intensified anti-vagrancy enforcement, as seen in the Statute of Cambridge (1388), which required laborers to obtain lordly or manorial permission before leaving their home hundred, under threat of arrest as vagabonds.[16] Idle or able-bodied beggars faced public whipping on market days, with recidivists liable to branding or further corporal punishment, reflecting a policy of territorial settlement to curb mobility and compel labor attachment rather than provide sustenance.[17] These statutes, building on the 1349–1351 framework, prioritized deterrence of perceived idleness—causally linked to post-plague labor scarcity—over charitable aid, establishing precedents for viewing the able-bodied poor as a disciplinary rather than welfare concern.[18]Tudor and Early Stuart Reforms

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, enacted between 1536 and 1541 under King Henry VIII, systematically dismantled over 800 religious houses across England, fundamentally altering the landscape of charitable provision for the poor. Prior to the dissolution, monasteries served as primary centers for alms distribution, offering food, shelter, and monetary aid to the destitute through daily "doles" and almonries, which formed a cornerstone of ecclesiastical welfare.[19] [20] This voluntary system relied on moral suasion rooted in Christian doctrine, channeling tithes, bequests, and surplus production to support a significant portion of the indigent population without direct state intervention.[21] The crown's seizure of monastic assets, valued at approximately £1.3 million in lands and buildings by 1540, transferred vast wealth to royal coffers and favored courtiers, but failed to replicate the institutions' charitable output.[22] This abrupt termination of monastic doles exacerbated existing poverty pressures from population growth and economic shifts, leading to a marked increase in vagrancy and begging as former recipients sought alternative means of survival.[19] [23] Historical analyses contend that the dissolution not only removed a key safety net but also intensified regional disparities, with northern England suffering greater hardship due to heavier reliance on monastic support.[24] In response to the ensuing surge in "sturdy vagabonds"—able-bodied wanderers deemed idle—the Parliament of 1535-1536 passed the Act for Punishment of Sturdy Vagabonds and Beggars (27 Hen. 8 c. 25), mandating local authorities to compel such individuals into labor, with penalties including whipping, stocks, and, for repeat offenders, branding or execution.[25] This legislation marked an initial pivot toward coercive state mechanisms for poverty management, contrasting the prior ecclesiastical emphasis on voluntary charity, yet it provided no systematic replacement for the lost alms, highlighting the government's incomplete assumption of welfare responsibilities.[26] Scholars argue this gap propelled the eventual development of secular poor laws, as the crown prioritized asset acquisition over charitable continuity.[19] [22]Vagrancy Acts and Early Taxation

The Dissolution of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1541 disrupted traditional ecclesiastical charity, which had annually distributed an estimated £9,000 to £15,000 in alms to the poor, exacerbating vagrancy as former monastic dependents and displaced laborers swelled the ranks of the mobile indigent.[27] [28] Tudor legislators responded by enacting Vagrancy Acts that targeted "sturdy beggars" and wanderers, distinguishing between the deserving impotent poor and the able-bodied idle, whom they held causally responsible for their plight through refusal to work.[29] These statutes emphasized deterrence via corporal and coercive measures over indefinite sustenance, reflecting a policy calculus that idleness threatened social order and economic productivity more than sporadic misfortune.[30] The Vagabonds and Beggars Act of 1530 (22 Hen. VIII c. 12) initiated this framework by mandating the whipping of apprehended vagabonds—defined as those without fixed abode or employment—and their return to their birthplaces for restraint by relatives or parish officials.[31] Escalation followed in the 1547 Act for the Punishment of Vagabonds (1 Edw. VI c. 3), which authorized enslavement for two years of repeat offenders, including branding and forced labor under the enslaver's direction, with provisions for the relief of genuinely impotent poor through local collections.[31] The 1572 Vagabonds Act (14 Eliz. c. 5) further intensified penalties, classifying unlicensed fortune-tellers, minstrels, and self-employed peddlers as vagrants; first offenders faced whipping and ear-boring, while recidivists endured execution as felons if unclaimed by a parish.[30] [29] Justices of the peace enforced these through periodic searches, aiming to immobilize the wandering poor and compel settlement in home parishes.[32] Parallel to punitive measures, early compulsory taxation emerged to fund localized relief, filling the void left by dissolved monastic resources. In 1547, London pioneered a mandatory poor tax levied on inhabitants according to means, marking the first statutory compulsion for urban poor support.[33] [34] This model expanded nationally with the 1572 Poor Relief Act, which required justices to assess and rate parishioners proportionally for a poor fund, appointing overseers to collect and distribute aid while registering the impotent poor for ongoing provision.[33] [32] These rates targeted the sedentary deserving poor, excluding vagrants, and laid groundwork for parish-based financing without central subsidy, prioritizing self-reliant local mechanisms over royal alms.[34]Parish Responsibilities and 1601 Act

The statutes of 1598 and the consolidating Poor Relief Act of 1601 formalized compulsory, parish-based poor relief in England, establishing the core principles of the Old Poor Law amid economic pressures from harvest failures in the 1590s and rising vagrancy.[1] [35] These measures built on earlier Tudor legislation, such as the 1563 Poor Law, by mandating that each parish assume responsibility for its deserving poor through locally levied rates, shifting from ad hoc charity to a structured, ratepayer-funded system administered by elected officials.[36] The 1601 Act required parishes to select two or more overseers of the poor annually, often alongside churchwardens, to assess local needs, collect a poor rate from owners and occupiers of land, houses, and tithes proportional to their value, and distribute relief accordingly.[37] [38] Funds supported three distinct categories: the "impotent poor," including the elderly, infirm, blind, and orphans unable to work, who received sustenance at home or in parish stocks; the able-bodied unemployed, compelled to undertake provided labor such as spinning or weaving materials supplied by overseers; and pauper children over seven, who were apprenticed to trades or set to work until maturity, with boys until age 24 and girls until 21 or marriage.[39] Justices of the peace supervised implementation, auditing accounts and resolving rate disputes to maintain fiscal restraint and local control.[37] Complementing these provisions, the 1662 Settlement Act addressed potential exploitation by restricting relief to those with established settlement in the parish, defined by birthright, apprenticeship, service, or 40 days' continuous residence without challenge.[40] [41] Parishes could petition magistrates to remove likely dependents—such as vagrants or recent migrants—back to their settlement of origin, curbing inter-parish migration for benefits and reinforcing accountability by tying relief to verifiable local ties.[42] This framework prioritized self-sufficiency and deterrence of idleness, with rates initially modest but scaling to fund relief equivalent to roughly 1 percent of national income by the mid-17th century, underscoring the system's emphasis on parochial oversight over centralized aid.[43]Old Poor Law Administration (1601-1834)

Local Parish Systems

The Old Poor Law (1601–1834) administered poor relief through a decentralized parish-based system, with each parish functioning as an autonomous unit responsible for identifying and supporting its own deserving poor, including the impotent (aged, infirm, or orphaned) and, to a lesser extent, the able-bodied unemployed.[44] Parish vestries—meetings of rate-paying inhabitants—held primary authority, annually appointing two or more overseers of the poor from among local householders to assess needs, distribute aid, and levy poor rates proportional to parishioners' property values and local circumstances.[45] This structure allowed significant flexibility, as vestries tailored relief to community-specific factors like harvest outcomes or migration pressures, often blending cash allowances, provisions in kind (such as food or clothing), and labor requirements where recipients performed parish tasks like road maintenance.[46] Relief modalities distinguished between outdoor aid, delivered in recipients' homes to sustain family units and independence, and indoor provision in parish-maintained almshouses or rudimentary workhouses, reserved mainly for the destitute unable to subsist outside.[47] Outdoor relief predominated under the Old Poor Law, reflecting a cultural and practical preference for non-institutional support that minimized disruption to household economies and social bonds, though indoor options expanded in parishes with dedicated facilities for the chronically dependent.[48] Overseers documented distributions in annual accounts, ensuring accountability while adapting to seasonal or idiosyncratic local demands, such as apprenticing pauper children to trades within the parish.[49] Empirical records indicate that by the 1770s, poor relief sustained roughly 5 to 10 percent of England's population across parishes, with recipient shares consistently higher in rural southern counties (often exceeding 10 percent) than in urban centers or northern regions, due to agrarian vulnerabilities like fluctuating grain prices and settlement laws restricting mobility.[1] This variation underscored the system's community-driven responsiveness, as southern vestries faced greater pressure from landless laborers, prompting scaled-up rates without uniform national mandates.Outdoor Relief Practices

Outdoor relief constituted the predominant mode of assistance under England's Old Poor Law from 1601 to 1834, delivering direct subsidies to impoverished households outside institutional settings to sustain the impotent poor—namely the aged, disabled, widows, and orphans—who were deemed deserving of aid without labor requirements.[1] Parish overseers, elected annually, assessed eligibility through local knowledge and provided relief via weekly cash doles averaging 1-2 shillings per person in southern England by the early 19th century, scaled to family size and local wage levels.[46] This approach contrasted with indoor relief by permitting recipients to remain in familial homes, thereby minimizing disruption to community networks and avoiding the punitive connotations of workhouses, which were rare before the 1720s and served only a fraction of paupers. Common provisions included not only monetary payments but also in-kind support such as food rations, fuel allowances, clothing distributions, and rent payments to prevent eviction, with maternity grants occasionally extended to support lying-in women through parish-funded midwives or basic necessities.[48] Medical aid formed a key component, as overseers reimbursed apothecaries and surgeons for treating indigent patients at home, covering costs for remedies and visits that alleviated acute illnesses without necessitating removal to infirmaries.[1] Administration occurred at parish "pay tables," where relief was disbursed biweekly or monthly after vestry review, fostering personalized oversight but relying heavily on informal neighbor testimonies for verification. By 1776, outdoor relief accounted for over 80% of total poor expenditures in many rural parishes, reflecting its scalability amid rising pauperism from enclosure and population growth.[46] This system yielded benefits in preserving household autonomy and social cohesion, as recipients could continue informal labor or kin-supported activities, reducing the familial fragmentation observed in institutional alternatives and aligning with communal norms of charity.[44] Empirical analyses of parish accounts indicate it effectively curbed starvation and vagrancy by supplementing inadequate harvests or seasonal unemployment, with relief scales often tied to bread prices to maintain minimal subsistence. However, lax monitoring enabled abuses, including able-bodied impostors claiming infirmity or exaggerated household needs, as documented in vestry minutes from counties like Berkshire and Wiltshire, where overseers noted recurrent disputes over false claims inflating rates by 10-20%.[50] Causally, outdoor relief mitigated short-term destitution by bridging income gaps in a pre-industrial economy marked by volatile employment, yet it inadvertently dulled work incentives for marginal laborers, as payments frequently exceeded full-time earnings for low-skilled tasks in southern agricultural districts by the 1790s, per contemporary rate assessments.[51] Historians drawing on overseers' records argue this fostered dependency cycles, with pauper numbers rising 200-300% in relief-heavy parishes during industrialization, though counter-evidence from northern regions suggests modest scales limited disincentive effects, attributing expansions more to demographic pressures than moral hazard.[52] Overall, while preserving dignity through home-based aid, the practice's decentralized nature prioritized immediate relief over long-term self-sufficiency, straining parish finances without uniform fraud controls.[53]Speenhamland Allowance System

The Speenhamland Allowance System was devised by local magistrates in Berkshire, England, on May 6, 1795, during a meeting at the Pelican Inn in the parish of Speenhamland near Newbury, amid acute food price inflation triggered by poor harvests and the ongoing French Revolutionary Wars.[54][55] The system supplemented the wages of agricultural laborers and other low earners through parish poor rates, ensuring family income reached a subsistence threshold calibrated to the price of a gallon loaf of bread per person—deemed the "right to live by bread"—adjusted for household size, with allowances provided in cash, bread, or flour equivalents.[1] For instance, a laborer with a wife and three children might receive full supplementation when bread exceeded 1 shilling per gallon loaf if his earnings fell short, tapering as wages rose to half the subsistence level where relief ceased entirely; this formula avoided direct wage fixing by magistrates, instead treating relief as a top-up to existing pay. Funded exclusively by local poor rates levied on landowners and occupiers rather than employers, the system sought to avert rural unrest and vagrancy following widespread enclosure acts that displaced smallholders into wage dependency, while maintaining labor supply for agriculture without compelling migration to urban areas.[56] By the early 1800s, variants had proliferated across southern and midland England, with adoption in parishes across at least 20 counties including Kent, Essex, Oxfordshire, and Wiltshire, often formalized in magistrates' tables or vestry resolutions that mirrored the Berkshire model.[57] Early observers, including economists David Ricardo and Thomas Malthus, critiqued the system for effectively subsidizing employers by enabling them to pay wages below subsistence, as ratepayers absorbed the shortfall, which discouraged labor mobility and bargaining for higher pay; parish records from adopting areas show real wages stagnating or declining relative to productivity gains in agriculture during this period.[58][56] Expenditure data corroborates the fiscal strain, with national poor rates escalating from approximately £2 million annually in the 1770s to over £7 million by 1815—more than tripling in nominal terms amid population growth from 7.5 million to 11 million—attributed in part to the wage-supplement mechanism's expansion under Speenhamland practices, though war-induced price volatility contributed. This approach prioritized short-term stability over market incentives, fostering dependency where relief became an entitlement tied to low-wage employment rather than idleness alone.[59]Early Workhouse Experiments

Early experiments with institutional poor relief in England included houses of correction established under the 1601 Poor Law, which aimed to detain and employ vagrants and the idle poor through compulsory labor. By the 1690s, larger urban workhouses emerged under Corporations of the Poor, with about a dozen such facilities created by parliamentary acts to house and set to work the impotent poor in cities like Bristol and Norwich.[60] These institutions enforced strict regimens, including hard tasks such as spinning wool or oakum-picking, but their deterrent effect was limited, as many able-bodied individuals evaded commitment through flight or resistance.[61] The Workhouse Test Act of 1722, formally the Poor Relief Act (9 Geo. 1 c. 7), marked a significant legislative push by authorizing parishes to erect, buy, or rent workhouses and to condition relief on residents performing labor therein, effectively testing the "genuineness" of pauper claims by making indoor conditions deliberately austere.[62] Overseers could deny outdoor aid to those refusing entry, aiming to reduce rates by promoting self-reliance or migration to settlement areas.[45] Despite this, adoption was sparse; parliamentary returns indicate only around 1,800 parishes operated workhouses by 1776, covering a fraction of England's approximately 15,000 parishes.[63] Conditions within these early workhouses were harsh to discourage dependency, featuring meager diets, regimented schedules with mandatory prayers and labor from dawn, and separation of families to undermine appeal.[61] Labor often proved unprofitable, yielding minimal income while incurring high building and maintenance costs, leading to frequent escapes, inmate unrest, and guardian reluctance to expand.[45] Consequently, indoor relief housed fewer than 15 percent of paupers by the late 18th century, with most parishes favoring cheaper outdoor allowances that sustained the able-bodied at home without institutional overhead.[1] This preference underscored the experiments' mixed outcomes, as the workhouse test deterred some but failed to supplant decentralized parish aid broadly.[63]Industrial Era Pressures

Escalating Poor Rates

Total expenditure on poor relief in England and Wales escalated dramatically from £1.72 million levied in the year ending Easter 1776 to approximately £8 million annually by the early 1830s, reflecting a quadrupling in nominal terms amid rising demands.[64] [1] This surge imposed a heavy per capita burden on ratepayers, reaching up to 10 shillings per head annually in heavily affected southern parishes by the 1820s, equivalent to a substantial portion of average laborer wages.[65] The increase was not uniform but concentrated in the period from the 1770s onward, coinciding with the onset of accelerated industrialization and demographic pressures. Key drivers included the displacement of rural laborers through widespread enclosure of common lands, which converted arable fields to pasture and reduced opportunities for small-scale farming, forcing thousands into wage dependency and pauperism.[66] Concurrently, inflationary effects from the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) and Napoleonic Wars (1799–1815) eroded purchasing power, amplifying relief costs as grain prices spiked and real wages stagnated for agricultural workers.[67] Population growth exacerbated these strains, with empirical data from parish records showing higher fertility rates among relief-dependent families, as subsidies effectively lowered the marginal cost of additional children, leading to larger households and sustained demand on rates.[65] Regional disparities highlighted the uneven impact: southern and midland agricultural parishes, reliant on underemployed day laborers, experienced the sharpest rate hikes, often exceeding 20% annual increases during harvest failures or postwar demobilization.[65] In contrast, northern counties like Lancashire and Yorkshire benefited from emerging industrial employment in textiles and mining, where higher factory wages reduced pauperism incidence and kept per capita relief lower, sometimes under half the southern levels.[65] This north-south gradient underscored how economic transitions buffered some areas while overwhelming traditional agrarian systems elsewhere, contributing to fiscal exhaustion in vulnerable locales by the 1830s.[1]Child Labor and Urban Poverty

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, English parishes under the Old Poor Law frequently apprenticed pauper children, including orphans, to factory owners in the burgeoning cotton and textile industries, particularly from the 1780s to the 1820s, as a means to reduce relief expenditures while providing purported vocational training.[68] These apprentices, often aged under 10, were bound to distant mills through parish contracts funded by local poor rates, with mill owners receiving children in exchange for nominal oversight and sustenance, though enforcement was lax.[69] A substantial portion of early factory labor derived from such pauper apprenticeships, as parishes sought to offload dependents amid rising urban demand for cheap workers.[68] Conditions in these mills proved lethal for many child apprentices, with parliamentary inquiries revealing widespread abuse, including 12- to 16-hour shifts in hazardous environments leading to deformities, exhaustion, and elevated mortality from diseases like tuberculosis and respiratory ailments exacerbated by poor ventilation and overcrowding.[70] Bioarchaeological analysis of 19th-century pauper apprentice remains confirms systemic mistreatment, with skeletons exhibiting rickets, nutritional deficiencies, and trauma indicative of forced labor, and government reports noting minimal interventions despite documented cases of over 2,000 affected paupers.[71] The 1819 Factory Act attempted restrictions, but pauper apprentices were exempted until the 1833 Act, by which time thousands had perished or been incapacitated, straining parish relief further as surviving families sought support for disabled children.[68] Rapid urbanization during the Industrial Revolution intensified pauperism, as rural migrants flooded cities like Manchester and Leeds, overwhelming parish relief systems designed for agrarian vagrancy rather than chronic urban unemployment and slum-dwelling destitution.[1] Vagrancy laws, rooted in pre-industrial settlement rules, proved inadequate for containing itinerant factory workers displaced by mechanization, resulting in makeshift outdoor relief supplements to family incomes amid disease outbreaks in unsanitary tenements, where typhus and cholera claimed disproportionate pauper lives.[3] Poor rates escalated as urban parishes funded child apprenticeships or wage subsidies, inadvertently subsidizing factory owners' exploitative pay scales, which critics like parliamentary investigators argued perpetuated dependency by enabling employers to hire at subsistence levels below market wages for free labor.[70][1]Gilbert's Act Reforms

The Relief of the Poor Act 1782, commonly known as Gilbert's Act after its sponsor Thomas Gilbert, permitted groups of parishes to voluntarily unite into districts to collectively manage poor relief, primarily through the establishment of shared workhouses or poor houses.[1] These facilities were designated exclusively for the impotent poor—including the elderly, infirm, sick, and orphaned children—explicitly excluding able-bodied paupers to avoid punitive confinement for those capable of work.[72] The Act emphasized productive employment within the institutions to offset costs, alongside provisions for medical care and infirmaries, marking a shift toward more targeted support for the vulnerable rather than broad deterrence.[73] Implementation proceeded on an opt-in basis, with parishes required to formally adopt the provisions, leading to the formation of approximately 70 Gilbert unions by 1800, concentrated in southern and midland counties.[74] In adopting areas, the consolidated administration often yielded economies of scale, such as reduced per-parish overheads and better-organized labor for inmates, which lowered relief expenditures in select locales during the late 18th century. However, these savings proved localized and insufficient to curb the broader escalation of poor rates, as demographic pressures and agricultural fluctuations continued to drive demand for aid.[1] Despite its innovations, the Act retained significant constraints inherent to the permissive Old Poor Law framework. Outdoor relief remained available, particularly for able-bodied laborers, undermining incentives for institutional employment and perpetuating fragmented parish-level discretion.[75] By prioritizing accommodation for the dependent without stringent measures to deter non-impotent claims, it failed to address rising pauperism among the working population, contributing to sustained fiscal strains even as workhouse provision expanded modestly.[76] Adoption varied widely due to local resistance and administrative hurdles, limiting its national reach prior to the more coercive reforms of later decades.Political Economy Critiques

Thomas Malthus, in his 1798 An Essay on the Principle of Population, contended that the English Poor Laws fostered population growth that outpaced subsistence resources, thereby intensifying poverty, vice, and misery. He argued that relief provisions weakened incentives for prudence by diminishing the "power and will to save" among the lower classes, encouraging early marriages and larger families without corresponding increases in food production, as the safety net removed natural checks like hunger and delayed gratification.[77] Malthus observed that such systems promoted dependency, stating that "the poor laws of England... continue that system of depopulation which has been so generally fatal to the industry and morality of the peasantry," ultimately advocating for their gradual abolition to restore self-reliance and moral discipline.[78] David Ricardo extended these concerns in his 1817 On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, asserting that poor relief subsidies artificially depressed wages to mere subsistence levels, as employers could pay less knowing parish rates supplemented income, thereby undermining labor productivity and capital accumulation. In Chapter 18 on poor rates, Ricardo explained that these levies, falling primarily on rents and profits, distorted market signals and reduced the farmer's net income while inflating laborers' gross receipts, leading to higher food prices and diminished incentives for agricultural improvement.[79] He warned that without repeal, poor rates could absorb the entire economic surplus, perpetuating a cycle where wages failed to rise with technological progress or population controls, as relief insulated workers from full market discipline.[80] These critiques were bolstered by empirical trends, such as the sharp escalation in poor relief expenditures; real per capita spending rose at an average annual rate of approximately 1 percent from 1748–50 to 1832–34, with southern English rural areas seeing relief claims exceed 10–15 percent of the population by the 1820s, correlating with stagnant wages and rising rates amid post-war agricultural depression.[81] Nassau William Senior echoed Ricardo in early writings, viewing subsidies as moral hazards that fostered idleness by guaranteeing support irrespective of effort, though he emphasized deductive political economy principles over immediate data. Critics like Malthus and Ricardo portrayed relief as exacerbating rather than alleviating poverty through distorted incentives, contrasting with defenders who saw it as a vital stabilizer against harvest failures and unemployment shocks, yet acknowledging its role in enabling employer wage suppression.[82]New Poor Law Era (1834 Onward)

Royal Commission and Principles

The Royal Commission on the Poor Laws, appointed by the Whig government in August 1832 under the chairmanship of the Bishop of London, was tasked with investigating the administration and practical operation of the Elizabethan Poor Law system amid escalating poor rates that had risen from approximately £2 million in the 1770s to over £7 million annually by the early 1830s.[83] The commission, comprising economists like Nassau William Senior and influenced heavily by its secretary Edwin Chadwick—a Benthamite reformer—conducted inquiries primarily through assistant commissioners who gathered evidence from over 10,000 parishes, focusing on southern and midland agricultural districts where outdoor relief was widespread.[84] Their 1834 report concluded that generous outdoor relief, particularly systems like Speenhamland allowances supplementing wages, had demoralized independent laborers by removing incentives to seek employment or maintain self-reliance, effectively pauperizing the able-bodied working class and inflating rates through dependency cycles.[83] Central to the commission's findings was the principle of less eligibility, which posited that conditions of relief must be rendered less desirable than those of the worst-paid independent laborer in the same district to deter idleness and restore labor discipline; this required confining able-bodied paupers to workhouses with regimented labor, diet, and discipline calibrated below the independent laborer's standard.[83] The report advocated abolishing outdoor relief for the able-bodied, arguing it subsidized low wages by employers and encouraged early marriages and population growth among the improvident, drawing on Malthusian concerns about unchecked relief fostering vice and reducing productivity.[84] To implement these reforms uniformly, the commission recommended establishing a centralized Poor Law Commission with authority to form parishes into larger poor law unions governed by elected boards of guardians, thereby overcoming fragmented local administration that perpetuated abuses.[83] The commission's analysis relied on statistical returns from 1770 to 1833 showing disproportionate rate burdens in arable farming areas—up to 10-15% of rental value in some southern counties—attributing this to relief policies rather than broader economic pressures like post-Napoleonic agricultural depression.[83] However, critics later noted the inquiry's selective emphasis on southern evidence of dependency, with limited engagement of northern industrial districts where wage labor markets and factory employment had fostered greater self-reliance and lower per capita relief expenditures, potentially understating regional variations in labor dynamics.[85] These principles directly informed the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which enacted the central commission and union framework to enforce deterrence over indulgence.[84]Indoor Relief and Workhouses

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 mandated indoor relief as the primary mechanism for supporting the able-bodied unemployed, confining them to workhouses administered by Poor Law Unions to enforce the principle of less eligibility—ensuring workhouse conditions were inferior to those of the lowest-paid independent laborer.[86] This shift aimed to deter idleness by requiring inmates to perform laborious tasks, such as picking oakum (unraveling old ropes for ship caulking) or breaking stones, under regimented schedules that began at dawn and included mandatory religious services.[87] Inmates wore distinctive uniforms, received a spartan diet of gruel, bread, and limited meat, and adhered to silence rules during meals to minimize comforts and reinforce discipline.[88] A core deterrent feature was the separation of families upon admission: men, women, and children were housed in segregated wards, with husbands and wives isolated except for rare supervised visits, and children placed under strict oversight to prevent generational dependency.[86] Workhouses were designed or retrofitted en masse after 1834, with over 500 facilities operational by the mid-1840s as unions consolidated parishes into larger administrative districts, enabling economies of scale in construction and management.[89] These institutions housed up to thousands in larger urban examples, prioritizing uniformity in rules via central Poor Law Commission directives, though local guardians retained some discretion in enforcement.[90] Implementation yielded initial fiscal successes, with poor rates declining by approximately 20-30% in southern and midland counties by the late 1830s through reduced pauper rolls, as the threat of workhouse entry discouraged applications for relief among the marginally employable.[91] Pauperism numbers fell sharply— from over 1 million recipients in 1834 to under 300,000 by 1841—fostering greater stigma around institutionalization and prompting many to seek private or familial support instead.[86] Children, comprising a significant portion of inmates, were mandated to receive at least three hours of daily instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic, often by resident schoolmasters, marking an improvement over pre-1834 neglect though curricula remained basic and punitive.[92] Critics, including early inspectors and local reformers, decried the regime's harshness—evident in reports of malnutrition, disease outbreaks, and suicides—as excessively punitive, arguing it inflicted undue suffering on the vulnerable while failing to address root unemployment causes.[93] Resistance manifested in northern industrial districts, where guardians delayed union formation and inmates occasionally rioted against separations or labor demands, as in isolated 1837-1838 disturbances tied to implementation delays.[94] Despite such backlash, the workhouse test endured as the Act's emblematic tool for enforcing self-reliance among the able-bodied.[88]Outdoor Relief Debates

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 prohibited outdoor relief for the able-bodied poor, mandating indoor relief in workhouses to enforce the principle of less eligibility and deter dependency, while permitting exceptions for the impotent poor, including the aged, infirm, widows, and orphans.[1] These exceptions allowed guardians discretion to provide non-institutional aid such as cash or food allowances to vulnerable groups unable to enter workhouses, reflecting a recognition that total deterrence was impractical for those deemed genuinely incapable of self-support.[48] Proponents of continued outdoor relief argued it was more humane and economical for the impotent, avoiding the separation of families and harsh workhouse conditions, and enabling recipients to remain in familiar community settings where private charity or kin support could supplement aid.[1] Critics, aligned with the 1834 Royal Commission's principles, contended that such relief undermined the system's deterrent intent by blurring distinctions between indoor and outdoor conditions, fostering evasion—such as able-bodied claimants obtaining medical certificates to qualify as infirm—and perpetuating pauperism by reducing incentives for thrift or employment.[95] Empirical data from unions showed widespread non-compliance, with outdoor relief comprising up to 80% of expenditures in some southern counties by the 1840s, as guardians prioritized local stability over central mandates.[1] The Bastardy Clauses of the 1834 Act, which shifted full financial responsibility for illegitimate children to unmarried mothers to discourage immorality, intensified debates by increasing reliance on outdoor relief for single mothers and their offspring, often classified as impotent; these were partially reformed in the 1844 Poor Law Amendment Act, easing paternity affiliation procedures and allowing fathers' involvement to mitigate pauperism without fully endorsing outdoor aid.[96] Radicals like William Cobbett decried restrictions on outdoor relief as cruel and insufficient, warning they exacerbated destitution and risked social unrest among the vulnerable.[97] Conservatives, fearing revolutionary fervor akin to Chartist agitations, advocated selective outdoor provisions to maintain order, viewing total abolition as politically untenable amid industrial hardships.[90] These tensions persisted, culminating in the 1870s Crusade Against Out-Relief, which sought stricter curbs but acknowledged the enduring role of exceptions for non-able-bodied paupers.[1]Irish Famine Applications

The Irish Poor Law system was extended to Ireland via the Poor Relief (Ireland) Act of 31 July 1838, which established a network of 130 poor law unions centered on workhouses, financed by local property taxes and administered by boards of guardians under centralized oversight from the Poor Law Commission in Dublin.[98] [99] This framework, modeled on the English New Poor Law, emphasized indoor relief in austere workhouses to deter dependency, with capacities designed for around 800 inmates per union, totaling roughly 100,000 nationwide by 1845.[100] When potato blight struck in 1845, triggering the Great Famine through 1852, the system rapidly collapsed under mass destitution, as Ireland's rural poor had become perilously dependent on the potato crop—yielding up to 12 tons per acre on small, subdivided plots but vulnerable to total failure due to monoculture of a single susceptible variety, Phytophthora infestans, amid population pressures exceeding 8 million.[101] Workhouses, intended to enforce "less eligibility" by making relief harsher than low-wage labor, were overwhelmed; by early 1847, inmate numbers peaked at over 250,000, often double or triple designed capacities, with facilities like Cork's housing 4,400 in space for 2,000, leading to rampant disease and mortality rates up to 20-30% annually in some unions.[102] [103] Centralized directives from London prioritized fiscal restraint and local funding, exacerbating overload as ratepayers—primarily absentee landlords—defaulted on contributions amid falling rents and evictions, forcing unions into bankruptcy and inconsistent relief.[104] To alleviate pressure, the Temporary Relief Act of February 1847 authorized soup kitchens, which by mid-year fed up to 3 million daily with minimal rations, funded partly by Treasury grants and Quaker contributions, providing a short-term bridge from public works schemes that had proven inefficient due to wage inflation and corruption.[105] However, as a deliberate temporary measure, kitchens closed by September 1847, reverting reliance to the strained Poor Law under the 1847 Extension Act, which permitted limited outdoor relief for the able-bodied "destitute poor" but reinforced workhouse primacy, resulting in renewed indoor crowding and fever epidemics.[106] Critics, including contemporaries like Poulett Scrope, faulted centralized British administration for delayed, parsimonious responses constrained by Malthusian ideology and laissez-faire principles, which viewed famine as a corrective to overpopulation and potato-centric subsistence farming, thereby exacerbating an estimated 800,000 to 1.5 million excess deaths from starvation and typhus.[107] [104] Charles Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary to the Treasury, defended this approach in The Irish Crisis (1848), arguing that expansive aid discouraged self-reliance and agrarian reform, empirically observing that relief dependency perpetuated subdivision of holdings and hindered diversification toward sustainable crops like grains.[108] Debates persist on whether failures stemmed primarily from London-imposed austerity—evident in slow Treasury disbursements and rejection of direct food imports—or local mismanagement, including guardian corruption and landlord clearances, though causal analysis underscores pre-famine structural vulnerabilities like tenure systems favoring tillage over mixed farming as amplifying the blight's impact beyond relief inadequacies.[109]Economic and Social Analyses

Labor Market Distortions

The Speenhamland system, adopted in numerous southern English parishes from 1795, supplemented low wages with parish allowances scaled to family size and bread prices, enabling employers to reduce cash payments while shifting costs to ratepayers. This mechanism distorted labor markets by undermining wage competition, as workers had less incentive to seek higher-paying opportunities or improve productivity, knowing relief would bridge shortfalls. Economic historians, synthesizing evidence from parish records and contemporary accounts, have concluded that the system contributed to lower wages and reduced output in agriculture, with allowances effectively capping earnings and discouraging mechanization or skill development during a period of rising population pressures from 1780 to 1834.[110][111] Compounding these effects, the Poor Law's settlement provisions, codified in the 1662 Act of Settlement and enforced through removal orders, confined paupers to their parish of legal settlement—typically acquired by birth, apprenticeship, or five years' residence—thereby restricting geographic mobility. Parishes issued thousands of removal orders annually to repatriate newcomers deemed likely to claim relief, preventing labor flows to industrializing regions like the Midlands and North, where demand for workers was surging. This immobility preserved labor surpluses in rural areas, elevating poor rates while suppressing wage convergence and efficient resource allocation, as laborers remained tied to low-productivity locales rather than migrating to higher-wage urban jobs.[112][113] The New Poor Law of 1834 addressed these distortions through the "less eligibility" doctrine, mandating that workhouse conditions and relief be inferior to the earnings of the lowest-paid free labor, thereby curtailing outdoor allowances for the able-bodied and compelling greater workforce participation. Implementation in Poor Law Unions progressively reduced pauperism rates, with able-bodied recipients falling from over 40% of total relief in 1833 to under 10% by 1840, channeling labor into private employment and supporting industrial expansion by alleviating subsidy-induced idleness. Data from southern unions show nominal agricultural wages stabilizing or modestly increasing post-reform—e.g., day rates for unskilled laborers rising from about 8-10 pence in 1830 to 10-12 pence by 1840—correlated with declining relief expenditures and heightened labor supply, though causality remains debated amid concurrent economic growth.[94][114] From an Austrian economic perspective, poor relief subsidies under both regimes fostered moral hazard, as guaranteed support diminished workers' incentives for diligence, entrepreneurship, or risk-bearing, leading to persistent underemployment and skill atrophy rather than market-driven advancement. Ludwig von Mises and aligned analysts contended that such interventions disrupted voluntary exchange, subsidizing idleness at the expense of productive effort and perpetuating dependency cycles observable in rising pauper rolls from the 1780s onward.[115][116]Incentives for Dependency

The provision of family allowances under the Old Poor Law, particularly through systems like Speenhamland, subsidized income based on household size, incentivizing larger families and early marriages as a means to secure higher relief payments, thereby contributing to Malthusian population pressures that exacerbated poverty rather than alleviating it.[117][118] Thomas Malthus argued that such relief removed natural checks on population growth, fostering dependency by rewarding reproduction over self-reliance, as subsidies effectively lowered the costs of child-rearing for the poor.[119] Bastardy allowances further distorted incentives, as parishes often covered maintenance for illegitimate children, reducing the financial risks for unmarried mothers and fathers, which correlated with rising illegitimacy rates from approximately 4% of births in the mid-18th century to over 6% by 1800, with some rural parishes reaching 20-30% by the early 19th century due to the perceived ease of parish support.[96] This system undermined paternal responsibility and thrift, as empirical patterns showed higher illegitimacy in areas with generous outdoor relief, prompting the 1834 reforms to shift burdens back to mothers in hopes of deterring such behavior.[121] Pauper auctions, where parishes bid out able-bodied paupers to the lowest-cost bidder for maintenance, aimed to minimize expenditures but inadvertently promoted idleness by assigning individuals to guardians who prioritized cheap upkeep over productive labor, often resulting in minimal oversight and no requirement for work contributions.[122] Originating in Elizabethan practices and persisting into the 19th century, these auctions commodified the poor, discouraging personal initiative as bidders competed on price rather than rehabilitation, with historical accounts documenting cases of neglect that reinforced cycles of dependency.[123] Overall, these mechanisms eroded incentives for self-sufficiency, as evidenced by the doubling of annual pauper numbers from roughly 500,000 in the 1780s to over 1 million by 1830, even amid economic growth and rising wages in agriculture and industry, indicating that relief policies actively cultivated pauperism rather than responding solely to exogenous hardship.[124] Critics like Malthus and contemporary economists contended that by guaranteeing subsistence regardless of effort, the system penalized thrift and industriousness, leading to stagnant labor mobility and higher long-term relief costs.[118][117]Stabilizing Effects and Empirical Outcomes

The English poor relief system contributed to social stability by mitigating unrest during periods of economic strain, such as those following enclosures, through provision of subsistence that reduced the incidence of food riots and protests. Empirical analysis of county-level data from 1650 to 1815 demonstrates a statistically significant negative correlation between per capita poor relief expenditures and food riot frequency, with a 0.293-unit increase in relief linked to roughly a 50% reduction in riots during the late 17th to late 18th centuries.[125] This stabilizing effect held as relief expenditures rose to approximately 2% of national income by the late 18th century, providing a safety net absent in continental Europe where lower per capita spending—such as France's level at less than one-seventh of England's in the 1780s—correlated with higher volatility.[126] Localized parish administration enabled flexible responses tailored to the "deserving" poor, such as the elderly and infirm, allowing variations in relief forms that supported community cohesion without uniform rigidity. In northern and western regions, lower relief dependency fostered self-reliance through proto-industrial activities, contrasting with higher southern expenditures where up to 13% of the rural population received aid annually by the early 19th century; this regional divergence highlights viable alternatives to heavy reliance on rates, as northern areas sustained stability via employment opportunities rather than subsidies.[52][127] Relief also underpinned England's anomalous population expansion—from under 6 million in 1700 to over 16 million by the 1830s—by subsidizing family sizes and averting Malthusian crises or mass starvation, countering the low-fertility norms of western Europe through aid to large households comprising 5-15% of the population at any time.[126] Claims of unqualified humanitarian triumph, often advanced in progressive narratives, overlook inefficiencies evidenced by escalating poor rates that strained property taxes and diverted resources from productive investment, yielding short-term order at the expense of dynamism. Economic analyses indicate that while relief curbed immediate chaos, it imposed long-term costs via work disincentives—such as effective marginal tax rates approaching 100% in some parishes—and restricted labor mobility by anchoring recipients to natal parishes, potentially elevating fertility and suppressing wage-driven growth.[52] By the early 19th century, these dynamics eroded stabilizing benefits, as relief inadvertently fueled population pressures that outpaced its capacity, spurring rather than quelling unrest in enclosure-disputed areas.[125] Conservative critiques emphasize this trade-off: temporary aversion of revolt deferred structural reforms, subsidizing stagnation over innovation, though post-1834 evidence of minimal population fallout suggests exaggerated prior distortions.[52]References

- https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/downloadpdf/display/[book](/page/Book)/9781847425317/ch013.pdf?pdfJsInlineToken=1271307883&inlineView=true