Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interstate 68

View on Wikipedia

I-68 highlighted in red | |||||||

| Route information | |||||||

| Maintained by WVDOH and MDSHA | |||||||

| Length | 113.15 mi[1] (182.10 km) | ||||||

| Existed | 1991–present | ||||||

| Tourist routes | |||||||

| NHS | Entire route | ||||||

| Major junctions | |||||||

| West end | |||||||

| |||||||

| East end | |||||||

| Location | |||||||

| Country | United States | ||||||

| States | West Virginia, Maryland | ||||||

| Counties | West Virginia: Monongalia, Preston Maryland: Garrett, Allegany, Washington | ||||||

| Highway system | |||||||

| |||||||

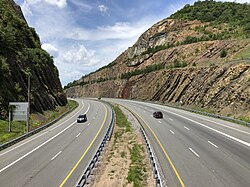

Interstate 68 (I-68) is a 113.15-mile (182.10 km) Interstate Highway in the U.S. states of West Virginia and Maryland, connecting I-79 in Morgantown, West Virginia, east to I-70 in Hancock, Maryland. I-68 is also Corridor E of the Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS). From 1965 until the freeway's construction was completed in 1991, it was designated as U.S. Route 48 (US 48). In Maryland, the highway is known as the National Freeway, an homage to the historic National Road, which I-68 parallels between Keysers Ridge and Hancock. The freeway mainly spans rural areas and crosses numerous mountain ridges along its route. A road cut at Sideling Hill exposed geological features of the mountain and has become a tourist attraction.

US 219 and US 220 overlap I-68 in Garrett County and Cumberland, respectively, and US 40 overlaps with the freeway from Keysers Ridge to the eastern end of the freeway at Hancock.

The construction of I-68 began in 1965 and continued for over 25 years, with completion on August 2, 1991. While the road was under construction, it was predicted that economic conditions would improve along the corridor for the five counties connected by I-68: Allegany, Garrett, and Washington in Maryland and Preston and Monongalia in West Virginia. The two largest cities connected by the highway are Morgantown, West Virginia, and Cumberland, Maryland. Although the freeway serves no major metropolitan areas, it provides a major transportation route in western Maryland and northern West Virginia and also provides an alternative to the Pennsylvania Turnpike for westbound traffic from Washington DC and Baltimore.

Various West Virginia officials have proposed extending the highway westward to the Ohio River valley, ending in either Moundsville, or Wheeling, West Virginia. An extension to Moundsville was approved by federal officials at one point but shelved due to funding problems.

History

[edit]Predecessors

[edit]Prior to the construction of the freeway from Morgantown to Hancock, several different routes carried traffic across the region. West Virginia Route 73 (WV 73) extended from Bridgeport to Bruceton Mills, serving regions now served by I-79 (Bridgeport to Morgantown) and I-68 (Morgantown to Bruceton Mills). After the I-68 freeway, then known as US 48, was completed in West Virginia, the WV 73 designation was removed. Portions of the road still exist as County Route 73 (CR 73), CR 73/73, and CR 857. Between I-68's exit 10 at Cheat Lake and exit 15 at Coopers Rock, I-68 was largely built directly over old WV 73's roadbed.

At Bruceton Mills, WV 73 ended at WV 26, which, from there, runs northeast into Pennsylvania, becoming Pennsylvania Route 281 at the state line and meeting US 40 north of the border. From there, eastbound traffic would follow US 40 into Maryland. I-68 now parallels US 40 through western Maryland.[2]

US 40 followed the route of the National Road through Pennsylvania and Maryland. The National Road was the first federally funded road built in the U.S., authorized by Congress in 1806. Construction lasted from 1811 to 1837, establishing a road that extended from Cumberland to Vandalia, Illinois. Upon the establishment of the U.S. Numbered Highway System in 1926, the route of the National Road became part of US 40.[3]

Cumberland Thruway

[edit]

In the early 1960s, as the Interstate Highway System was being built throughout the U.S., east–west travel through western Maryland was difficult, as US 40, the predecessor to I-68, was a two-lane country road with steep grades and hairpin turns.[4] In Cumberland, the traffic situation was particularly problematic, as the usage of US 40 exceeded the capacity of the city's narrow streets.[4] Traffic following US 40 through Cumberland entered through the Cumberland Narrows and followed Henderson Avenue to Baltimore Avenue. After the construction of I-68, this route through Cumberland became US 40 Alternate (US 40 Alt.).[5]

Construction began on one of the first sections of what would become I-68, the Cumberland Thruway, on June 10, 1965.[6] This portion of the highway, which consists of a mile-long (1.6 km) elevated bridge, was completed and opened to the public on December 5, 1966.[7] The elevated highway connected Lee Street in west Cumberland to Maryland Avenue in east Cumberland, providing a quicker path for motorists traveling through the town on US 40 and US 220. The Cumberland Thruway was extended to US 220 and then to Vocke Road (Maryland Route 658, or MD 658) by 1970.[8][9] Problems quickly emerged with the highway, especially near an area called "Moose Curve". At Moose Curve, the road curves sharply at the bottom of Haystack Mountain, and traffic accidents are common.[10]

Corridor E

[edit]| Location | Morgantown, West Virginia–Hancock, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Existed | 1965–1991 |

In 1965, the Appalachian Development Act was passed, authorizing the establishment of the ADHS, which was meant to provide access to areas throughout the Appalachian Mountains that were not previously served by the Interstate Highway System. A set of corridors was defined, comprising 3,090 miles (4,970 km) of highways from New York to Mississippi. Corridor E in this system was defined to have endpoints at I-79 in Morgantown, West Virginia, and I-70 in Hancock, Maryland. At the time, there were no freeways along the corridor, though construction on the Cumberland Thruway began that year.[6][11] It was this corridor that would eventually become I-68.[12]

The construction of Corridor E, which was also designated as US 48, took over 20 years and hundreds of millions of dollars to complete.[4] The cost of completing the freeway in West Virginia has been estimated at $113 million (equivalent to $483 million in 2024[13]).[14] The cost of building I-68 from Cumberland to the West Virginia state line came to $126 million (equivalent to $539 million in 2024[13]); the portion between Cumberland and Sideling Hill cost $182 million (equivalent to $373 million in 2024[13]); and the section at Sideling Hill cost $44 million (equivalent to $90.1 million in 2024[13]).[4]

Much of the work in building the freeway was completed during the 1970s, with US 48 opened from Vocke Road in LaVale to MD 36 in Frostburg on October 12, 1973, and to MD 546 on November 1, 1974.[4][15] On November 15, 1975, the West Virginia portion and a 14-mile (23 km) portion from the West Virginia state line to Keysers Ridge in Maryland opened, followed by the remainder of the freeway in Garrett County on August 13, 1976.[4]

In the 1980s, the focus of construction shifted to the east of Cumberland, where a 19-mile (31 km) section of the road still had not been completed. The first corridor for the construction to be approved by the Maryland State Highway Administration (MDSHA) ran south of US 40. This corridor would have bypassed towns in eastern Allegany County, such as Flintstone, leaving them without access to the freeway, and would have passed directly through Green Ridge State Forest, the largest state forest in Maryland. This proposed corridor provoked strong opposition, largely due to the environmental damage that would be caused by the road construction in Green Ridge State Forest. Environmental groups sued MDSHA in order to halt the planned construction, but the court ruled in favor of the state highway administration. In 1984, however, MDSHA reversed its earlier decision and chose an alignment that closely paralleled US 40, passing through Flintstone and to the north of Green Ridge State Forest. Construction on the final section of I-68 began May 25, 1987, and was completed on August 2, 1991.[4][16]

Designation as I-68

[edit]

Though the National Freeway was designated as US 48, as the completion of the freeway neared, the possibility of the freeway being designated as an Interstate Highway came up. In the 1980s, the project to improve US 50 between Washington DC and Annapolis to Interstate Highway standards had been assigned the designation of I-68. MDSHA, however, later concluded that adding additional route shields to the US 50 freeway would not be helpful to drivers since about half the freeway already had two route designations (US 50 and US 301) and drivers on the freeway were already familiar with the US 50 designation.[17] This made the designation to be applied to that freeway more flexible, and so, in 1989, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), the organization composed of the various state departments of transportation that decides route numbering in the U.S., approved MDSHA's request to renumber the US 50 freeway from I-68 to I-595.[18] That same year, AASHTO approved changing US 48's designation to I-68.[18] This change took effect upon the completion of the last section of the National Freeway on August 2, 1991.[4]

With the completion of I-68 and the change in its route number, the US 48 designation was removed. In 2002, AASHTO approved the establishment of a new US 48, this time for the Corridor H highway from Weston, West Virginia, to Strasburg, Virginia.[19] This marks the third time that the US 48 number has been assigned to a highway, the first use being for a highway in California that existed in the 1920s.[20]

Incidents

[edit]Numerous crashes and incidents have occurred on I-68. On June 1, 1991, a gasoline tanker descending into downtown Cumberland from the east attempted to exit the freeway at exit 43D, Maryland Avenue. The tanker went out of control and overturned as the driver tried to go around the sharp turn at the exit. Gasoline began to leak from the damaged tanker, forcing the evacuation of a three-block area of Cumberland. Approximately 30 minutes later, the tanker exploded, setting eight houses on fire. The fire caused an estimated $250,000 in damages (equivalent to $510,000 in 2024[13]) and prompted MDSHA to place signs prohibiting hazardous materials trucks from exiting at the Maryland Avenue exit.[21][22][23]

On May 23, 2003, poor visibility due to fog was a major contributing factor to an 85-vehicle pileup on I-68 on Savage Mountain west of Frostburg. Two people were killed and nearly 100 people were injured. Because of the extent of the wreckage on the road, I-68 remained blocked for 24 hours while the wreckage was cleared.[24] In the aftermath of the pileup, the question of how to deal with fog in the future was discussed. Though the cost of a fog warning system can be considerable, MDSHA installed such a system in 2005 at a cost of $230,000 (equivalent to $350,000 in 2024[13]).[25][26] The system alerts drivers when visibility drops below 1,000 feet (300 m).[26]

Effect on surrounding region

[edit]

One of the arguments in favor of the construction of I-68 was that the freeway would improve the poor economic conditions in western Maryland. The economy of the surrounding area has improved since the construction of the freeway, especially in Garrett County, where the freeway opened up the county to tourism from Washington DC and Baltimore. Correspondingly, Garrett County saw a sharp increase in population and employment during and after the construction of the road, with full- and part-time employment increasing from 8,868 in 1976 to 15,334 in 1991.[27] Economic difficulties, however, remain in Allegany and Garrett counties.[28] There were concerns over loss of customers to businesses that have been cut off from the main highway due to the construction of the new alignment in the 1980s, leading to protests when then-Governor Harry Hughes visited the Sideling Hill road cut when it was opened.[29]

Proposed extension

[edit]In the 1990s, there was discussion about a future westward extension to I-68. Such an extension would connect the western terminus of I-68 in Morgantown to WV 2 in Moundsville. A 1989 proposal had suggested a toll road be built along this corridor.[30] In 2003, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) approved the extension, paving the way for federal funding and for the road to become part of the National Highway System on completion.[31] The project, however, ran into problems due to lack of funds, and, in 2008, West Virginia Governor Joe Manchin suggested dropping the project altogether, making construction of a westward extension of I-68 unlikely in the near future.[32]

In 2014, Marshall County officials brought the extension of I-68 up again as a way for oil companies to have easier access to drill into the area, likely by fracking. Much like the second leg of PA 576 (Southern Beltway) in the Pittsburgh area, an extension of I-68 is being spurred in response to the Marcellus natural gas trend. If the extension were to be built, it would also include a widening of WV 2 to four lanes and would cost an estimated $5 million per mile ($3.1 million/km). It is expected that the project would be divided into two legs, first from Morgantown to Cameron and then Cameron to Moundsville.[33]

Others have proposed extending I-68 to Wheeling, West Virginia, and connecting it with I-470.[34]

Route description

[edit]| mi[1] | km | |

|---|---|---|

| WV | 32.06 | 51.60 |

| MD | 81.09 | 130.50 |

| Total | 113.15 | 182.10 |

I-68 spans 113.15 miles (182.10 km), connecting I-79 in Morgantown, West Virginia, to I-70 in Hancock, Maryland, across the Appalachian Mountains. The control cities—the cities officially chosen to be the destinations shown on guide signs—for I-68 are Morgantown, Cumberland, and Hancock.[35] I-68 is the main route connecting Western Maryland to the rest of Maryland.[36] I-68 is also advertised to drivers on I-70 and I-270 as an "alternate route to Ohio and points west" by MDSHA.[37]

West Virginia

[edit]

I-68 begins at exit 148 on I-79 near Morgantown and runs eastward, meeting with US 119 one mile (1.6 km) east of its terminus at I-79. I-68 turns northeastward, curving around Morgantown, with four interchanges in the Morgantown area—I-79, US 119, WV 7, and CR 857 (Cheat Road). Leaving the Morgantown area, I-68 again runs eastward, intersecting WV 43, which provides access to Cheat Lake and Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Near this interchange, I-68 passes over Cheat Lake and climbs a steep ascent out of Cheat Canyon.[38]

Entering Preston County, the route intersect CR 73/12, which provides access to Coopers Rock State Forest. In contrast to the Morgantown area, the portion of Preston County that I-68 crosses is more rural, with the only town along the route being Bruceton Mills. In Bruceton Mills, I-68 meets WV 26. I-68 meets CR 5 (Hazelton Road) at its last exit before entering Garrett County, Maryland.[38]

The region of West Virginia through which the freeway passes is rural and mountainous. There are several sections that have steep grades, especially near the Cheat River Canyon, where there is a truck escape ramp.[39]

The peak traffic density in terms of annual average daily traffic (AADT) on I-68 in West Virginia is 32,900 vehicles per day at the interchange with I-79 in Morgantown. The traffic gradually decreases further eastward, reaching a low point at 14,600 vehicles per day at the Hazelton exit.[40]

Maryland

[edit]

After entering Garrett County, I-68 continues its run through rural areas, crossing the northern part of the county. The terrain through this area consists of ridges that extend from southwest to northeast, with I-68 crossing the ridges through its east–west run. The first exit in Maryland is at MD 42 in Friendsville. I-68 ascends Keysers Ridge, where it meets US 40 and US 219, both of which join the highway at Keysers Ridge.[5] The roadway that used to be the surface alignment of US 40 parallels I-68 to Cumberland and is now designated as US 40 Alt. I-68 crosses Negro Mountain, which was the highest point along the historic National Road that the freeway parallels east of Keysers Ridge. This is the source of the name of the freeway in Maryland: the National Freeway.[4] Three miles (4.8 km) east of Grantsville, US 219 leaves the National Freeway to run northward toward Meyersdale, Pennsylvania, while I-68 continues eastward, crossing the Eastern Continental Divide and Savage Mountain before entering Allegany County.[5]

The section of I-68 west of Dans Mountain in Allegany County is located in the Allegheny Mountains, characterized in Garrett County by a series of uphill and downhill stretches along the freeway, each corresponding to a ridge that the freeway crosses. In Allegany County, the freeway crosses the Allegheny Front, where, from Savage Mountain to LaVale, the highway drops in elevation by 1,800 feet (550 m) in a distance of nine miles (14 km).[41][42]

The traffic density on I-68 in Garrett County is rather sparse compared to that of Allegany County. At the Maryland–West Virginia state line, there is an AADT of 11,581 vehicles per day. This density increases to its highest point in Garrett County at exit 22, where US 219 leaves I-68, at 19,551. At the Allegany County line, the traffic density decreases slightly to 18,408. In Allegany County, the vehicle count increases to 28,861 in LaVale and to the freeway's peak of 46,191 at the first US 220 interchange (exit 42) in Cumberland. East of Cumberland, the vehicle count decreases to 16,551 at Martins Mountain and stays nearly constant to the eastern terminus of I-68 in Hancock.[5]

After entering Allegany County, I-68 bypasses Frostburg to the south, with two exits, one to Midlothian Road (unsigned MD 736) and one to MD 36. Near the MD 36 exit is God's Ark of Safety church, which is known for its attempt to build a replica of Noah's Ark. This replica, which currently consists of a steel frame, can be seen from I-68.[43]

East of Frostburg, I-68 crosses a bridge above Spruce Hollow near Clarysville, passing over MD 55, which runs along the bottom of the valley. The freeway runs along the hillside above US 40 Alt. in the valley formed by Braddock Run. Entering LaVale, I-68 has exits to US 40 Alt. and MD 658 (signed southbound as US 220 Truck). I-68 ascends Haystack Mountain, entering the city of Cumberland. This is the most congested section of the highway in Maryland. The speed limit on the highway drops from 70 mph (110 km/h) in LaVale to 55 mph (89 km/h) until the US 220 exit and to 40 mph (64 km/h) in downtown Cumberland.[5] This drop in the speed limit is due to several factors, including heavy congestion, closely spaced interchanges, and a sharp curve in the road, known locally as "Moose Curve", located at the bottom of Haystack Mountain. This section of the highway was originally built in the 1960s as the Cumberland Thruway, a bypass to the original path of US 40 through Cumberland.[4]

Until 2008, signs at exit 43A in downtown Cumberland labeled the exit as providing access to WV 28 Alt. Because of this, many truckers used this exit to get to WV 28. This created problems on WV 28 Alt. in Ridgeley, West Virginia, as trucks became stuck under a low railroad overpass, blocking traffic through Ridgeley. To reduce this problem, MDSHA removed references to WV 28 Alt. from guide signs for exit 43A and placed warning signs in Cumberland and on I-68 approaching Cumberland advising truckers to instead use exit 43B to MD 51, which allows them to connect to WV 28 via Virginia Avenue, bypassing the low overpass in Ridgeley.[44]

At exit 44 in east Cumberland, US 40 Alt. meets the freeway and ends, and, at exit 46, US 220 leaves I-68 and runs northward toward Bedford, Pennsylvania. I-68 continues across northeastern Allegany County, passing Rocky Gap State Park near exit 50. In northeastern Allegany County, the former US 40 bypassed by I-68 is designated as MD 144, with several exits from I-68 along the route. I-68 crosses several mountain ridges along this section of the highway, including Martins Mountain, Town Hill, and Green Ridge, and the highway passes through Green Ridge State Forest. East of Green Ridge State Forest, MD 144 ends at US 40 Scenic, another former section of US 40.[5]

I-68 crosses into Washington County at Sideling Hill Creek and ascends Sideling Hill. The road cut that was built into Sideling Hill for I-68 can be seen for several miles in each direction and has become a tourist attraction as a result of the geologic structure exposed by the road cut.[45]

On the east side of Sideling Hill, I-68 again interchanges with US 40 Scenic, at its eastern terminus at Woodmont Road. Here, US 40 Scenic ends at a section of MD 144 separate from the section further west. Four miles (6.4 km) east of this interchange, I-68 ends at I-70 and US 522 in the town of Hancock.[5]

Exit list

[edit]| State | County | Location | mi[a] | km | Exit | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Virginia | Monongalia | Morgantown | 0.0 | 0.0 | — | Western terminus; exit 148 on I-79 | |

| 1.1 | 1.8 | 1 | |||||

| 4.0 | 6.4 | 4 | |||||

| 6.9 | 11.1 | 7 | |||||

| Cheat Lake | 10.0 | 16.1 | 10 | ||||

| Preston | Pisgah | 14.5 | 23.3 | 15 | |||

| Bruceton Mills | 22.6 | 36.4 | 23 | ||||

| Hazelton | 28.5 | 45.9 | 29 | ||||

| 31.5 0.00 | 50.7 0.00 | West Virginia–Maryland state line | |||||

| Maryland | Garrett | Friendsville | 3.83 | 6.16 | 4 | ||

| Keysers Ridge | 13.82 | 22.24 | 14 | Cloverleaf interchange; western terminus of US 40/US 219 concurrency; signed as exits 14A (US 219) and 14B (US 40) | |||

| Grantsville | 19.20 | 30.90 | 19 | ||||

| 22.26 | 35.82 | 22 | Eastern terminus of US 219 concurrency; southern terminus of US 219 Bus. | ||||

| | 23.98 | 38.59 | 24 | Lower New Germany Road (MD 948D) | |||

| Finzel | 29.78 | 47.93 | 29 | ||||

| Allegany | Frostburg | 33.32 | 53.62 | 33 | Midlothian Road (MD 736) – Frostburg | ||

| 35.01 | 56.34 | 34 | |||||

| LaVale | 39.20 | 63.09 | 39 | No eastbound exit | |||

| 39.93 | 64.26 | 40 | No westbound entrance; Vocke Road is unsigned MD 658 | ||||

| | 41.54 | 66.85 | 41 | Westbound exit only | |||

| Cumberland | 42.32 | 68.11 | 42 | Western terminus of US 220 concurrency; includes unsigned westbound exit and eastbound entrance to Fletcher Drive | |||

| 43.59 | 70.15 | 43A | Beall Street / Johnson Street – Ridgeley, WV | Right-in/right-outs with Beall Street (westbound) and Johnson Street (eastbound) | |||

| 43.88 | 70.62 | 43B | |||||

| 43.90 | 70.65 | 43C | Downtown Cumberland | Eastbound entrance via exit 43B | |||

| 44.22 | 71.17 | 43D | Maryland Avenue | Right-in/right-out; no hazardous materials on westbound exit | |||

| 44.85 | 72.18 | 44 | Eastern terminus of US 40 Alternate | ||||

| 45.77 | 73.66 | 45 | Hillcrest Drive (MD 952) | Right-in/right-out | |||

| 46.47 | 74.79 | 46 | Naves Cross Road (MD 144) | Westbound exit and entrance; eastbound access is at exit 47 | |||

| 47.17 | 75.91 | 47 | Eastern terminus of US 220 concurrency; signed as exit 46 eastbound | ||||

| Rocky Gap State Park | 51.26 | 82.49 | 50 | Pleasant Valley Road (MD 948AD) – Rocky Gap State Park | |||

| | 52.50 | 84.49 | 52 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||

| Flintstone | 55.95 | 90.04 | 56 | ||||

| Green Ridge State Forest | 62.92 | 101.26 | 62 | ||||

| 64.19 | 103.30 | 64 | M.V. Smith Road (MD 948AL) | ||||

| | 68.72 | 110.59 | 68 | Orleans Road (MD 948Z) | |||

| | 71.64 | 115.29 | 72 | ||||

| Washington | | 73.59 | 118.43 | 74 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||

| | Sideling Hill Cut (rest area and welcome center) | ||||||

| | 77.15 | 124.16 | 77 | ||||

| Hancock | 81.09 | 130.50 | 82 | Eastern terminus; eastern terminus of US 40 concurrency; signed as exits 82A (south), 82B (east) and 82C (west/north); exit 1A on I-70 | |||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Starks, Edward (January 27, 2022). "Table 1: Main Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways". FHWA Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on September 20, 2023. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ Wilbur Smith Associates (July 1998). "Highway and Traffic Analysis" (PDF). ADHS Economic Evaluation. Appalachian Regional Commission. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Raitz, Karl & Thomson, George (1996). The National Road. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8018-5155-1. Retrieved October 11, 2008 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Maryland State Highway Administration (August 2, 1991). "Building the National Freeway" (PDF). Maryland Roads. Maryland State Highway Administration: 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Highway Information Services Division (December 31, 2013). Highway Location Reference. Maryland State Highway Administration. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- Garrett County (PDF).

- Allegany County (PDF).

- Washington County (PDF).

- ^ a b "Demolition in Path of Bridge to Begin". Cumberland News. June 10, 1965. p. 12.

- ^ "Cumberland Thruway Opened to Motorists". Cumberland News. December 5, 1966. p. 5.

- ^ "Next Phase of Thruway Bids Asked". Cumberland Evening Times. February 9, 1967. p. 27.

- ^ "New Freeway Sections Will Open Today". Cumberland News. October 18, 1969. p. 25.

- ^ "Transportation Department Head to Check Thruway". Cumberland Evening Times. July 28, 1972. p. 9.

- ^ Maryland State Roads Commission (1960). Map of Maryland (Map). c. 1:380,160. Annapolis: Maryland State Roads Commission. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Appalachian Regional Commission (2007). "Highway Program". Appalachian Regional Commission. Archived from the original on January 17, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ "I-68 Extension Gets Important Federal Endorsement". Steubenville, OH: WTOV-TV. September 9, 2003. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ "New Section of Freeway Now Open". Cumberland News. October 13, 1973. p. 8.

- ^ Raitz, Karl & Thompson, George (1996). The National Road. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-8018-5155-1.

- ^ Shaffer, Ron (January 12, 1990). "Tunnel Visions". Washington Times. p. E1. ProQuest 307243358. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering (June 7, 1989). "Report of the Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering to the Executive Committee" (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering (November 5, 2002). "Report of the Special Committee on U.S. Route Numbering to the Standing Committee on Highways" (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Bureau of Public Roads & American Association of State Highway Officials (November 11, 1926). United States System of Highways Adopted for Uniform Marking by the American Association of State Highway Officials (Map). 1:7,000,000. Washington, DC: United States Geological Survey. OCLC 32889555. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2013 – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ "Driver of Overturned Tanker Warns Residents Before Blasts". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Associated Press. June 2, 1991. p. 3.

- ^ Castaneda, Ruben (June 2, 1991). "Gasoline Truck Overturns; Leak Ignites 8 Md. Houses; Three-Block Area Evacuated in Cumberland". Washington Post. p. B5. ProQuest 307444525. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "Cumberland Fire Damage". The Washington Post. June 3, 1991. p. D3. ProQuest 307400909. Archived from the original on January 17, 2017. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ "85-Vehicle Pileup Kills Two in Western Maryland". CNN. May 23, 2003. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Wald, Matthew (June 18, 2003). "War on Road Fog Lacks Easy Solution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- ^ a b "Fog Warning System Installed on I-68". The Herald-Mail. Hagerstown, MD. July 3, 2005. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Bezis, Jason & Noyes, Kristin (November 5, 2008). "Economic Development History of I-68 in Maryland". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Beyers, Dan (September 8, 1992). "Mountain Road of Promise Slow to Lift Fortunes". The Washington Post. p. D1. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ Hughes, Harry Roe (2006). My Unexpected Journey. The History Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-59629-117-1.

- ^ Steelhammer, Rick (November 28, 2000). "I-68 Extension Hearings to be Next Week". Charleston Gazette. p. 2A.

- ^ Melling, Carol (October 31, 2003). "I-68 Extension Now Eligible for Federal Funding" (Press release). West Virginia Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Limann, Art (August 12, 2008). "Authority Won't Give Up on I-68 to Marshall". Wheeling News-Register. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Fluharty, Nate (September 15, 2014). "Plans Moving Forward for Moundsville-to-Morgantown Highway". Wheeling, WV: WTRF-TV. Archived from the original on September 16, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Swint, Howard (October 5, 2019). "Howard Swint: I-68 extension lynch pin for W.Va. development". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ Maryland State Highway Administration (2006). "Traffic Control Devices Design Manual" (PDF). Maryland State Highway Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Longfellow, Rickie (June 27, 2017). "Back in Time: Sideling Hill Mountain, I-68—Are We Going Over It or Around It?". General Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ Maryland State Highway Administration. Alternate Route to Ohio and Points West (Highway sign). Washington County: Maryland State Highway Administration. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ a b "I-68 in West Virginia" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ a b West Virginia Department of Transportation Program Planning and Administration Division (2008). General Highway Map: Monongalia County (PDF) (Map). 1:63,360. Charleston: West Virginia Department of Transportation. Sheet 2. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

{{cite map}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ West Virginia Department of Transportation (2007). Interstate System Average Daily Traffic: I-68 Morgantown to Maryland (PDF) (Report). West Virginia Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ Raitz, Karl & Thompson, George (1996). The National Road. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8018-5155-1.

- ^ "Topographic Map of Interstate 68 in Western Allegany County" (Map). Google Maps. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Cleary, Caitlin (April 16, 2006). "If the Flood comes Too Soon, this Ark Won't Be Quite Ready". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2006.

- ^ Moses, Sarah (December 23, 2008). "Signs Alert Truck Drivers to Low Overpass in Ridgeley". Cumberland Times-News. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Brezinski, David (1994). "Geology of the Sideling Hill Road Cut". Maryland Geological Society. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ West Virginia Department of Transportation Program Planning and Administration Division (2008). General Highway Map: Preston County (PDF) (Map). 1:63,360. Charleston: West Virginia Department of Transportation Program. Sheet 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

External links

[edit] Media related to Interstate 68 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Interstate 68 at Wikimedia Commons- Interstate Guide – I-68

- I-68 in West Virginia at AARoads.com

- I-68 in Maryland at AARoads.com

- I-68 at MDRoads.com

- West Virginia Roads - I-68

- Maryland Roads - I-68

- Roads to the Future - National Freeway (I-68)