Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

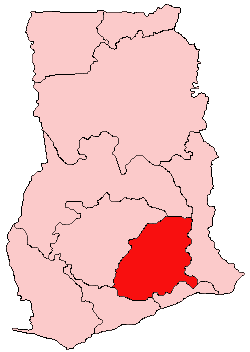

Kwahu

View on Wikipedia

Kwahu or Kwawu is an area and group of people that live in Eastern region of Ghana and are part of the Twi-speaking Akan group. The region has been dubbed Asaase Aban, or the Natural Fortress, given its position as the highest habitable elevation in the country. Kwahu lies in the Eastern Region of Ghana, on the western shore of Lake Volta. The Kwahus share the Eastern Region with the Akyem and Akuapem, as well as the Adangbe-Krobos. Among Kwahu lands, a significant migrant population works as traders, farm-hands, fisherfolk, and caretakers in the fertile waterfront 'melting pot' of Afram plains. These migrants are mostly from the Northern and Volta Regions, as well as, some indigenous Guans from the bordering Oti and Brong-Ahafo regions live in the Afram Plains area. Kwahus are traditionally known to be wealthy traders, owning a significant number of businesses and industries in Ghana.

History

[edit]The name Kwahu, according to historians, derives from its myths of origin, "The slave (akoa) died (wu)," which was based on an ancient prophecy that a slave would die so the wandering tribe of Akan would know where to settle. This resonates with the etymology of the Ba-wu-le (Baoulé) Akans of the Ivory Coast, whose Warrior Queen Awura Poku had to sacrifice her baby in order to cross the Komoe river. The myth was part of the historical stories of the Agona matriclan, the first paramount lineage of Kwawu, and was later adopted by the Bretuo-Tena matriclan (Twidan), who later replaced them. Other historians trace the name Kwahu to the dangers associated with making the mountainous terrain a habitat, as it became known as a destination of no return: go at your own peril or "ko wu" in the Twi language. This latter version is thought to have come either from their ancestral people in Mampong, who did not support fragmentation or from enemies who perished in trying to take the fight to the Kwahu in the treacherous mountains.

Kwahu people trace their origins to Adansi, like other forest Akan groups like the Akyem, Denkyira, Akwamu and Asantes. The first migration from Adansi happened long before the Asante Confederacy existed. Long before the Asante-Denkyira war of1699-1700, Nana Osei Twum, the first Chief Agonaman in the Adansi Morobem, his nephew Badu, his younger brother Kwasi Tititii and a slave Kofabra ("fetch it") together with Frempong Manso (who later founded Asante-Akyem stool land in the Asante Kingdom), Nana Ameyaw and Nana Adu Gyamfi, (founders of Asante Afidwase and Asante Gyamase respectively) fled from the cruelty of the King of Denkyira who had captured Adansi in about 1650, to find a new land. The group got divided, and the trekking Kwahu party led by Osei Twum moved up the mountains and stopped first at Dampong, whereupon Osei Twum and his party then moved on and discovered the Mpraeso Scarp. The trekking Kwahus continued to search for suitable land to settle. Thus, from Mount Apaku, where they first settled, they came across a stream with a rock in it shaped like a stone jar, and Osei Twum, interpreting this as a good omen, decided to settle there and called the place Obo-kuruwa or Bukuruwa, meaning stone jar. Another group from Mampong later settled in Kwahu. This is documented in K. Nkansah Kyeremateng's The Story of Kwawu.[1]

The paramount king of Kwawu resides at Abene, north of Abetifi towards the Volta. The strategic location of Abene, along with a dreaded militia that guarded the route (led by Akwamu warriors), helped stave off attempts by colonial forces to capture the Omanhene. Till this day, the road from Abetifi to the small enclave housing the king is plied with some unease, given the stories recounted.

Before their leaders seized the opportunities presented with the signing of the Bond of 1844, Kwahu was an integral part of the Asante Kingdom, attested by available maps of the period. Asante would wage punitive and protracted wars against fellow Akans, including Denkyira, Akwamu, Akyem, Fante, Assin, but never fought Kwahu. Abetifi (Tena matriclan) is the head of the Adonten (vanguard). Obo (Aduana, Ada, Amoakade) is the head of the Nifa (Right Division) Aduamoa (Dwumuana, Asona) is the head of the Benkum (Left Division). Pepease is the head of the Kyidom or rear-guard division.

As part of the Asante Empire, Kwawu had an Asante emissary, governor or ambassador at Atibie, next to Mpraeso, of the Ekuona matriclan. To indicate its independence from Asante in 1888, the Kwawu assassinated the Asante emissary in Atibie, about the time of the arrival of the Basel missionaries from Switzerland. Fritz Ramseyer had been granted a few days of rest during a stop at Kwahu while en route to Kumasi with his captors. He recovered quickly from a bout of fever while in the mountains. Upon gaining his freedom later from the Asantehene, he sought permission to build a Christian Mission in Abetifi, thereby placing the town on the world map and opening the area to vocational and evangelical opportunities. Although it remains a small town, Abetifi still draws the reputation of a Centre of Excellence in Education with various institutions from the ground up. A Bernese country house built by Ramseyer, typical of the Swiss "Oberland", is well-kept and remains a symbol of early Christian Missionary Zeal. Obo, traditionally pro-Ashanti, led the opposition against the Swiss.

Until recently, Kwahus, in comparison to other Akan groups such as the Ashanti and Fanti, shunned political activism, preferring to engage in business and trading activities. They are therefore usually under-represented in government appointments.

Eulogy

[edit]The spelling of "h" in this context is the official designation from the African Studies Centre at the University of Ghana and closely reflects the pronunciation. Swiss missionaries from Basel introduced the "h" to prevent the first syllable, "Kwa," from being pronounced as "eh". It's important to note that the "h" is not pronounced separately in the name. For Anglo-Germanic speakers, the pronunciation of "Ku-A-U" might be easier, while Francophone speakers will likely pronounce it as "KoU-AoU" without difficulty.

Educational institutions

[edit]Kwahu has several educational institutions across all the towns and villages. The Presbyterian Church has a university and teachers' training college in the town of Abetifi. Presbyterian University College is also located in Kwahu. There are also two nursing training institutions at Nkawkaw, owned and managed by the Catholic Church and a government nursing school at Atibie.

Below are some of the many secondary schools in Kwahu.

- St Peter's Senior High School

- Kwahu Tafo Senior High School

- Nkawkaw Senior High School, Kawsec located at Nkawkaw.

- Atibie Nursing and Midwifery training college

- Kwahu Ridge. Senior High Technical

- Mpraeso Senior High School

- St. Paul's Senior High School, Asakraka

- Kwahu Tafo Senior High School

- Bepong Senior High School

- Nkwatia Presbyterian Senior High School

- St. Dominic's Senior High School

- Abetifi Secondary Technical School

- Abetifi Presbyterian Senior High School

- St. Joseph Technical School

- Amankwakrom Fisheries Agricultural Technical Institute, Afram Plains

- Donkorkrom Agricultural Senior High

- Mem-Chemfre Community Senior High School

- St. Mary's Vocational and Technical Institute, Afram Plains

- Maame Krobo Community. Day School,

- St. Fidelis Senior High and Technical School

- Fodoa Community Senior High School

Economy

[edit]

The Kwahu, an Akan people living on the eastern border of Ashanti in Ghana, are well known for their business activities. An enquiry into the reasons for their predominance among the largest shopkeepers by turnover in Accra traced the history of Kwahu business activities back to the British-Ashanti War of 1874, when the Kwahu broke away from the Ashanti Confederacy, focusing on the rubber trade, which continued until 1914. Rubber was carried to the coast for sale, and fish, salt, and imported commodities, notably cloth, were sold on the return journey north. Other Kwahu activities at this time included trading in local products and African beads.

The development of cocoa in south-eastern Ghana provided opportunities for enterprising Kwahu traders to sell there the imported goods obtained at the coast. Previously, itinerant traders, the Kwahu began to settle for short periods in market towns. In the 1920s, the construction of the railway from Accra to Kumasi, growing road transportation, and the establishment of inland branches of the European firms reduced the price differences which had made trading inland so profitable. In the 1930s, the spread of the cocoa disease, swollen shoot, in the hitherto prosperous south-east, finally turned Kwahu traders' attention to Accra. Trading remained the most prestigious of Kwahu activities, and young men sought by whatever means they could to save the necessary capital to establish a shop.[2][3] Recent developments indicate that this enterprising group of people can provide the new entrepreneurial organization or capital needed for sophisticated setups in a developing country. Within the last few decades, Kwahus have advanced their portfolios and ventured into the acquisition of bigger assets in the manufacturing, hotel industries and command an enviable leadership position in the building materials and pharmaceutical sectors. [4] Kwahus probably own the most housing and commercial properties together with their Ashanti cousins in Accra and other Metropolitan Cities in the South of the country.

Geography

[edit]Access into Kwahu begins from Kwahu Jejeti, which shares a boundary with Akyem Jejeti (both communities are joint but separated by the Brim river), which is roughly 3 3-hour drive from the outskirts of Accra and approximately 140.9 km in distance. It lies midway in the road journey from Accra to Kumasi and serves as the gateway to a cluster of smaller towns set within the hills. Although the region doesn't have a lake or identical weather fauna, the mountainous profile resembles the Italian region overlooking Lago di Garda in Lombardy or the surroundings of Interlaken in Switzerland, with winding roads uphill towards Beatenberg. An aerial view of portions of the Allegheny Plateau in the United States provides another good description of Kwahu Country.

Temperatures may trail the normal readings for Accra and other cities of Ghana by up to 3 degrees at daytime and drop further at night, making the weather in Kwahu relatively cooler and more pleasant. The Afram River collects the major drainage of the Plateau and makes an impressive 100 km journey from Sekyere in Ashanti through Kwahu as a tributary to join the Volta Lake. Canoe fishing is big business along the vast shoreline and beyond the smaller expanse of water stretches, the fertile grounds of the plains are a huge agricultural paradise that is unquestionably one of Ghana's bread baskets.

Health

[edit]- Kwahu Government Hospital[5]

Language and culture

[edit]The term Kwahu also refers to the variant of Akan language spoken in this region by approximately 1,000,000 native speakers. Except for a few variations in stress, pronunciation, and syntax, there are no markers in the dialect of Akan spoken by the Kwahu versus their Ashanti or Akyem neighbours. Choice of words and names are pronounced closer to Akuapem Twi as in 1-Mukaase (Kitchen), 2-Afua (a girl's given day name for Friday), 3-Mankani (Cocoyam), etc., but not with the Akuapem tonation or accent. These three examples can quickly indicate the speaker's origin or source influence: Ashanti speakers would say Gyaade, Afia and Menkei for 1-3 above.

Originally of Ashanti stock, oral history details the two-phased migration of the Kwahu from the Sekyere-Efidwase-Mampong ancestral lands through Asante-Akyem Hwidiem to arrive at Ankaase, which is today near the traditional capital of Abene, before spreading out to other settlements with clan members from peripheral Akyem and various parts of the Ashanti heartland. The group that first settled at Abene was led by (M)Ampong Agyei, who is accepted as the Founder of Kwahu. Historical material supports this view that connects the Kwahu to kinsmen who built their capital at Oda.

The fallout with Frimpong Manso, Chief of Akyem (Oda), triggered a second wave of migration, believed to have resulted from the refusal of Kwahu to swear an oath of allegiance, making them de facto subjects, upon arrival at Hwidiem. Unsuccessful incursions by the Oda Chief Atefa into Kwahu territory on the plateau would subsequently earn him the title "Okofrobour": one who takes the battle to the mountains. The jagged escarpment, however, made Kwahu inaccessible, hence the old humour meme 'Asaase Aban', signifying a naturally fortified and indestructible Kwahu Country.

If Ashanti Twi is by and large the refined language standard, it is appropriate to view Kwahu Twi as the precious stone from which the jeweller styles a gem. There is a certain purity of pronunciation, call it crude, with little effort to polish sounds: Kwahu speakers would opt for "Kawa" (a ring) and not "Kaa", "Barima" (Man) instead of "Berma" and pronounce "Oforiwaa" not "Foowaa". Another slight difference is the preference for full sentences among the Kwahu: "Wo ho te sɛn?" (How are you?) in place of the shorter "Ɛte sɛn?" in Ashanti; Other examples are "Wo bɛ ka sɛ / Asɛ" (you might say, looks like); Ye firi Ghana / Ye fi Ghana (We are from Ghana) and other minor name or word preferences, pronunciations, sentence length, etc. that usually pass unnoticed.

The Mamponghene, who is next to the Ashantehene in hierarchy, and the Kwahuhene are historical cousins, hence both occupy Silver Stools with the salutation Daasebre. The culture of the people of Kwahu does not differ from the larger Akan Group. Inheritance practice is matrilineal, and women hold office, own property and can enter into contracts without restrictions. Typical of fellow Akans, Fufu is a must-have main meal towards the close of day, prepared from Cassava or another Carbohydrate Tuber called Cocoyam and pounded with Plantains. It is served alongside a semi-thickened soup.

Notable People

[edit]Edward Omane Boamah: Physician and former Minister for Communications of Ghana

Obuoba J.Adofo: Ghanaian Higlife Musician

Manaen Twum Ampadu: Former Flying officer

KiDi: Ghanaian singer-songwriter

Funny Face (Benson Nana Yaw Oduro Boateng): A comedian and actor

Tourist attractions

[edit]- Abetifi Stone Age Park

- Bruku Shrine - Kwahu Tafo

- Oku Falls - Bokuruwa

- The Gaping Rock- Kotoso

- The Highest Habitable Point in Ghana - Abetifi

- Oworobong Water Falls - Oworobong

- Ramseyer Route - Abetifi

- The Padlock Rock - Akwasiho

- Nana Adjei Ampong Cave - Abene

- The Seat of Paramountcy - Abene.

- Afram River - Afram Plains

Festivals

[edit]Paragliding Festival

[edit]The Ghana Tourism Authority in an attempt to promote domestic tourism, launched the Kwahu Easter Paragliding Festival at Atibie in Kwahu in 2005.[7][8] This festival is an annual event which is held during every Easter in the month of April.[7][9] During the event, seasoned pilots are invited to participate and thousands of people visit Odweano Mountain at Kwahu Atibie.[10][11]

Akwasidaekese Festival

[edit]This is celebrated annually as the last Akwasidae of the year. The festival provides the community to commune and communicate with their ancestors, take stock of their activities as a people, plan for the coming years and thank God for His protection and provision over the years.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ [url=https://books.google.com.gh/books/about/The_Story_of_Kwawu.html?id=tNkJAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y]

- ^ Garlick, Peter C. (November 1967). "The Development of Kwahu Business Enterprise in Ghana since 1874-An Essay in Recent Oral Tradition". The Journal of African History. 8 (3): 463–460. doi:10.1017/S0021853700007969. JSTOR 179831. S2CID 145518654. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Paul T (1988). African Capitalism: The Struggle for Ascendency. Cambridge University Press. p. 148. ISBN 9780521319669.

- ^ [url=https://www.academia.edu/107294496/The_Kwawu_resilient_entrepreneurial_ecosystems]

- ^ "GMR provides free medical services to 3,500 residents of Atibie in Eastern Region - MyJoyOnline.com". www.myjoyonline.com. 2021-08-15. Retrieved 2022-05-25.

- ^ "Tourist Attractions – Abetifi Constituency Portal". Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ a b "2020 Kwahu Easter Paragliding Festival launched". Citinewsroom - Comprehensive News in Ghana. 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ "Visit Ghana | Paragliding Festival". Visit Ghana. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ "2020 Kwahu Easter Paragliding Festival launched". Citinewsroom - Comprehensive News in Ghana. 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ "2019 Kwahu Paragliding Festival takes off". Graphic Online. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- ^ "2019 Kwahu Paragliding Festival takes off". Graphic Online. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- ^ "Obo Kwahu Celebrates Akwasidaekese Festival". www.ghanaweb.com. 30 November 2001. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

External links

[edit]Kwahu

View on GrokipediaGeography

Physical Landscape and Plateau Features

The Kwahu Plateau forms the uplifted southern edge of the Volta River Basin in southern Ghana, characterized by a prominent escarpment resulting from differential erosion of sedimentary layers.[7] This escarpment marks the southern limit of the Voltaian sedimentary basin, where younger Voltaian sandstones cap older underlying formations, creating steep scarps and elevated plateaus through erosional processes.[8] [9] The plateau extends approximately 190 kilometers in a northwest-southeast direction, with average elevations around 450 meters above sea level, rising to maxima of 762 meters in some areas.[10] [11] In specific districts like Kwahu East, the scarp ascends from 220 meters to 640 meters, featuring prominent peaks such as Abetifi at 610 meters.[12] The terrain includes dissected ridges and highlands, part of the broader central highlands between Koforidua and Wenchi, forming the Kwahu-Mampong-Koforidua ridge system with undulating plateaus and valleys.[13] Rivers originating from the plateau, including tributaries of the Volta system, have carved deep valleys into the landscape, contributing to its rugged topography and facilitating southward drainage toward the Gulf of Guinea.[7] The geological structure, dominated by Voltaian Supergroup strata, underlies the plateau's resistance to erosion, preserving its elevated form amid surrounding lower-lying plains and savannas.[8]Climate, Ecology, and Environmental Challenges

The Kwahu Plateau, situated at an average elevation of approximately 1,500 feet (460 meters), features a tropical climate with warm temperatures year-round and distinct wet and dry seasons typical of Ghana's eastern forest zone. In Nkawkaw, a key settlement in the region, average high temperatures reach 96°F (36°C) during the hottest months of February and March, while lows rarely drop below 70°F (21°C), with annual means between 75°F (24°C) and 88°F (31°C).[14] [15] Rainfall averages 50-60 inches annually, peaking from April to June (up to 5 inches or 127 mm monthly) and October, supporting vegetation growth before a drier harmattan period from December to February influenced by northeastern winds. These patterns align with Ghana's broader tropical humid conditions, though the plateau's elevation moderates extremes compared to lowland areas.[16] Ecologically, the region encompasses a dissected plateau landscape within the Southern Voltaian and Forest Dissected physiographic zones, historically dominated by moist semi-deciduous forests that form a critical watershed dividing Volta Basin rivers from those flowing to the Atlantic.[12] Native flora includes species adapted to seasonal rainfall, such as various hardwoods and understory plants, while fauna historically featured totemic animals revered in local traditions, contributing to biodiversity hotspots amid rocky outcrops and river valleys.[17] However, palaeoecological records from nearby sites indicate fluctuations tied to regional climate shifts, with modern ecosystems showing signs of fragmentation due to human activity.[18] Environmental challenges in Kwahu stem primarily from deforestation, which has substantially reduced original forest cover on the plateau through agricultural expansion, charcoal production, and fuelwood extraction, leading to soil nutrient depletion, erosion, and diminished watershed integrity.[19] [20] Rural solid waste management remains ineffective, with improper disposal in Kwahu East District causing soil and water pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and health risks from unmanaged household refuse.[21] Additional pressures include seasonal water scarcity exacerbated by land-use changes and intermittent pollution from upstream activities, prompting restoration initiatives like agroforestry projects and reliance on indigenous ecological knowledge, such as totemic protections, to mitigate habitat loss.[17][22] These issues highlight the tension between economic needs and ecosystem preservation in a highland area vital for regional hydrology.[23]History

Origins, Migration, and Early Settlement

The Kwahu people, a subgroup of the Twi-speaking Akan ethnic group, trace their origins to the broader Akan migrations into present-day Ghana, which occurred in successive waves between the 11th and 18th centuries, originating from regions further north or northeast before consolidating in forested southern areas.[24] Specific oral traditions link Kwahu ancestry to Ashanti (Asante) territories, particularly ancestral lands around Sekyere, Efidwase, and Mampong in the modern Ashanti Region, where they formed part of early Akan polities before internal conflicts prompted dispersal.[25] These accounts emphasize descent from Ashanti stock, with no evidence of direct northern non-Akan origins unique to Kwahu, distinguishing them from Guan or other indigenous groups in the region.[5] Migration to the Kwahu Plateau intensified in the 17th and 18th centuries, driven by frequent wars, chieftaincy disputes, and resource pressures within the expanding Asante Kingdom; groups departed from settlements such as Kuntanase, Pampasi, Juaso, Adansi, and Asante Mampong, seeking defensible high ground amid sibling rivalries and expansionist campaigns.[1] [26] Historical narratives describe phased movements, often in kinship-based bands under leaders like the Bokuruwa (Agona migrants) and Etena/Bratuo groups, who navigated southward through Akyem territories to evade Asante dominance, with the plateau's escarpments providing natural fortifications against raiders.[25] These migrations were not mass exoduses but incremental, involving hunters, farmers, and warriors who intermarried with sparse local populations, including possible pre-existing Kwaffo inhabitants whose kingdom predated Akan arrivals according to oral histories.[5][4] Early settlement focused on the elevated Kwahu Ridge, spanning approximately 150 kilometers in Ghana's Eastern Region, where communities established fortified towns like Abene (in the valleys) and Burukuwa (royal cores), prioritizing agrarian terraces for yam and cocoa cultivation alongside strategic trade routes overlooking the Volta Basin.[4] By the late 17th century, these pioneers had coalesced into a loose confederation of chiefdoms, with Abetifi and Atibie emerging as key centers; settlers from Abene assert primacy in lowland occupation, while Burukuwa lineages claim foundational royal authority, reflecting matrilineal Akan inheritance patterns adapted to the terrain's isolation.[25] This phase laid the groundwork for Kwahu's role as a semi-autonomous buffer against Asante incursions, with archaeological evidence of pottery and ironworking sites corroborating sustained habitation from the migration era, though precise dating remains reliant on oral corroboration due to limited excavations.[5]Pre-Colonial and Colonial Eras

The Kwahu people, a subgroup of the Akan ethnic group, migrated to their current territory on the Kwahu Plateau primarily from Asante interior locations such as Kuntanase, Pampasi, and Juaso, driven by frequent intertribal wars and internal conflicts within the Asante Kingdom during the 18th century.[1][4] This relocation to the elevated terrain provided strategic defensive advantages, allowing early settlers to monitor approaching threats from afar and establish fortified communities.[1] By the late 18th century, Kwahu had formed several independent states or paramountcies, including Abetifi, Atitem, and Nkawkaw, each governed by a paramount chief under the Akan matrilineal kinship system, with authority balanced by councils of elders and commoner assemblies.[27] Economically, pre-colonial Kwahu society centered on agriculture, producing yams, maize, and plantains, supplemented by small-scale gold mining and trade in commodities like kola nuts, which were exchanged with northern savanna traders and indirectly with European merchants on the coast through Akwamu and other intermediaries.[28] Social organization featured the asafo companies—military and regulatory groups of young commoner men—who enforced community rules, mediated disputes, and restrained chiefly abuses in political and economic spheres, reflecting a proto-democratic check on centralized power.[29] These institutions fostered a reputation for industriousness and mercantile acumen among the Kwahu, who leveraged their plateau position to control regional trade routes. In the colonial era, the 1844 Bond of 1844 between the British and Asante, which barred Asante military incursions south of the Pra River, enabled Kwahu states to break from tributary obligations to Asante and pursue autonomous alliances with British traders, enhancing access to European goods via Volta River routes.[30] The mid-19th century arrival of Basel Missionaries introduced Christianity, prompting widespread conversions by the 1850s and establishing schools that promoted literacy and Western education, though traditional beliefs persisted in syncretic forms.[31] Under British Gold Coast administration from 1874 onward, Kwahu integrated into the Eastern Province through indirect rule, preserving chieftaincy while introducing cash crops like cocoa and infrastructure such as roads, which spurred merchant class growth but also exacerbated social stratification between elites and asafo-led commoners.[29] By the early 20th century, colonial policies amplified economic differentiation in Kwahu, with increased trade and mission-driven development leading to urban centers like Atua and Mpraeso, yet traditional governance faced challenges from evolving class dynamics and British administrative oversight.[29] Kwahu avoided direct involvement in the Anglo-Asante Wars of the 1890s, benefiting from British victories that solidified colonial control over former Asante vassals, paving the way for post-1901 stability under the unified Gold Coast Colony.[32]Post-Independence Evolution and Key Events

Following Ghana's attainment of independence on March 6, 1957, the Kwahu traditional area, situated in the Eastern Region, underwent shifts aligned with national political centralization under President Kwame Nkrumah's Convention People's Party (CPP) regime, which implemented policies diminishing the authority of traditional chiefs through ordinances like the 1957 Chieftaincy Act and subsequent measures favoring state control over local governance.[33] These efforts included establishing Nkrumah-era institutions such as the Cocoa Service Division and Workers' Brigade in areas like Kwahu-Tafo, aimed at modernizing agriculture and labor organization, though both had largely dissolved by the late 1960s amid declining cocoa productivity and regime instability.[34] The 1966 military coup that ousted Nkrumah marked a turning point, enabling the partial revival of chieftaincy institutions nationwide, including in Kwahu, where traditional councils regained influence in local dispute resolution and development initiatives, though tensions persisted between modern state structures and customary authority.[35] Subsequent national upheavals, such as the 1972 coup overthrowing the Busia government, reverberated locally, contributing to economic disruptions but also fostering adaptive trading networks that sustained Kwahu's historical role as a commercial hub, bolstered by remittances from migration waves starting in the 1980s.[34] Economically, Kwahu's enterprising traders capitalized on regional cocoa expansion and internal markets, maintaining over 200 stores and kiosks in towns like Kwahu-Tafo by the 1970s, while infrastructure improvements, including electricity introduction around 1970, facilitated modernization such as television access and extended commercial hours.[34] The annual Easter festival emerged as a key driver of socioeconomic progress, attracting tourists and generating revenue for local businesses, infrastructure enhancements, and community cohesion through events like paragliding and cultural displays, with studies attributing positive impacts on employment and revenue since the late 20th century.[36] Chieftaincy evolution included the rise of "development chiefs," such as a post-1957 German missionary who funded schools and a stadium in Kwahu-Tafo, reflecting hybrid influences of external philanthropy on traditional roles.[34] However, disputes over succession and paramountcy have recurred, exemplified by the 2025 escalation involving rival enstoolments and claims of dual paramount stools, prompting interventions by the Eastern Regional House of Chiefs and heightened security measures amid bribery allegations and factional divisions.[37] [38] These conflicts underscore ongoing negotiations between customary law and statutory frameworks in post-independence Ghana.[35]Demographics and Society

Population Composition and Major Settlements

The Kwahu area, spanning multiple districts in Ghana's Eastern Region, had a combined population of approximately 535,765 residents as of the 2021 Population and Housing Census, distributed across Kwahu West Municipal (145,429), Kwahu East (79,726), Kwahu South (80,358), Kwahu Afram Plains North (66,555), and Kwahu Afram Plains South (163,707).[39][40][41][42] Sex ratios in these districts typically show a slight male majority, ranging from 53.3% to 53.4% male in the Afram Plains areas, reflecting patterns in rural and agricultural zones with higher male labor migration.[43][42] The population is predominantly ethnic Kwahu, a subgroup of the Akan people who speak a dialect of Twi, with smaller proportions of migrant groups including other Akan subgroups, Ewe, and northern ethnicities engaged in trade and farming.[31] Urban centers like Nkawkaw host notable migrant communities from across Ghana, drawn by commercial opportunities, though the core rural settlements remain overwhelmingly Kwahu in composition.[44] Major settlements in the Kwahu area cluster along the Kwahu Plateau escarpment and adjacent plains, serving as administrative, commercial, and cultural hubs. Nkawkaw, the largest urban center and capital of Kwahu West Municipal, functions as a key trading post with over 220 settlements in its district, supporting markets for cocoa, foodstuffs, and timber.[44] Abetifi, in Kwahu East District, is a prominent traditional and educational town, alongside Kwahu-Tafo, Nkwatia, Pepease, and Aduamoa, which host secondary schools, health facilities, and chieftaincy seats.[45] Mpraeso and Abene further anchor the plateau's northern ridge, with economies tied to agriculture, mining, and small-scale industry, while Afram Plains settlements like Tease emphasize fishing and farming on the Volta Lake periphery.[12] These towns, numbering over 100 across the core districts, exhibit dense clustering on elevated terrain for defense and resource access, with populations varying from several thousand in peri-urban areas to smaller village clusters.[44][45]Social Structure and Family Systems

The Kwahu people, as a subgroup of the Akan ethnic group, adhere to a matrilineal kinship system in which descent, clan membership, and inheritance are traced through the maternal line. Individuals are primarily affiliated with their mother's family, with the belief that blood lineage derives from the mother, leading to stronger social and economic ties to maternal kin over paternal or conjugal relations. Property inheritance typically passes from a maternal uncle (wofa) to his sister's children, emphasizing the role of the uncle in providing for and guiding nephews and nieces.[1][46][4] The extended family, known as abusua, forms the core social unit, encompassing living members, ancestors, and even the unborn, and functions as a mechanism for mutual support, conflict resolution, and maintaining societal order. It is headed by the abusuapanyin (family head), often the eldest male or female lineage member, assisted by a spokesperson (abusua kyeame). Kinship terminology distinguishes maternal relatives prominently, such as wofa for mother's brother, nakuma for aunt, nananom for grandparents, mma for children, and awofo for parents, reflecting the centrality of matrilineal bonds in daily life and obligations.[4] Marriage among the Kwahu is exogamous, prohibiting unions within the same clan, and requires consent and background investigations by both families to assess compatibility, health, and character, often involving gifts, drinks, and the symbolic ti-nsa (head-drinking) ceremony to confirm the match. The process is contractual rather than celebratory, with no formal bride-wealth; instead, a nominal payment or transfer of goods seals the union, and women frequently retain residence with their matrikin, especially if the husband lacks independent housing, resulting in over 40% of couples living separately. Divorce is common and straightforward, typically initiated by women over issues like adultery or infertility, with children remaining affiliated with the mother's lineage.[47][1][4][46] Family units enforce social norms, including prohibitions on marrying close relatives and gender-segregated roles where men focus on external affairs and women maintain domestic autonomy, though matrilineal ties often supersede conjugal ones in inheritance and support networks. This structure promotes lineage cohesion but contributes to high divorce rates, with the family arbitrating disputes through elders to preserve harmony.[47][4]Governance and Politics

Traditional Chieftaincy and Authority

The traditional chieftaincy system among the Kwahu adheres to the Akan model of matrilineal inheritance and decentralized authority, wherein leadership is vested in stools symbolizing ancestral continuity and communal custodianship.[1][4] The paramount chief, known as the Omanhene, holds ultimate authority over land allocation, customary dispute resolution, and the preservation of cultural norms, functioning as both spiritual guardian and administrative head of the Kwahu state.[5] Selection of the Omanhene occurs through enstoolment by a council of kingmakers, drawn from the royal Bretuo (Tena) clan, with endorsement from elders, the queen mother, and community representatives in Abene, the seat of paramountcy.[4][1] The Kwahu Traditional Council, convened at Abene, represents the highest deliberative body, harmonizing policies among constituent towns and divisions while overseeing development, conflict mediation, and ritual observances.[5] Beneath the Omanhene lies a hierarchical array of divisional chiefs (Mantsefo), organized into wings (nkyen) that originated from pre-colonial military formations, each assigned specific governance roles adapted to peacetime administration:- Adonten (headquartered at Abetifi, Agona clan): Serves as vanguard protectors, leading in frontline defense and initial conflict engagement.[1][4]

- Nifa (Obo, Aduana clan): Guards the right flank, contributing to strategic security and judicial oversight in eastern territories.[5][1]

- Benkum (Aduamoa): Manages left-wing operations, focusing on logistical support and boundary enforcement.[5]

- Kyidom (Pepease, Ekuona clan): Handles rear-guard duties, including supply chains, reinforcement, and resource mobilization.[5][1]

- Gyase (Atibie, Oyoko clan): Provides intimate protection to the Omanhene, enforcing palace protocols and internal order.[5][4]