Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Obuasi

View on Wikipedia

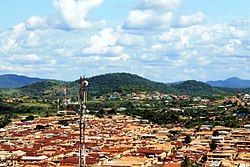

Obuasi is a gold mining town and is the capital of the Obuasi Municipal District in the Ashanti Region of Ghana.[2][3] It lies in the southern part of the Obuasi Municipal and is located about 63 km (39 mi) from Kumasi.[3] As of 2012, the town has a population of 175,043 people.[1] The current mayor (executive chief) of the town is Hon. Elijah Adansi-Bonah.[4][3][5]

Key Information

Obuasi is home to the Obuasi Gold Mine, one of the largest known gold deposits on Earth.[6][3] The Gold Coast region was named after the large amount of gold mined, historically at Obuasi and the neighbouring Ashanti Region.[3]

History

[edit]The area which makes up Obuasi have historically been mined for multiple centuries. The town became an important economic center after the discovery of a large gold deposit in 1897 and the building of a railway from Sekondi in 1902.[7]

Administration

[edit]Obuasi has a mayor–council form of government. The mayor, or executive chief, is appointed/approved by the town council, the Obuasi Municipal Assembly and the president of Ghana. The current mayor of the town is Hon. Elijah Adansi-Bonah.[4]

Demographics

[edit]About 81.7% of the population is Christian, of which 33.2% are Pentecostal/Charismatic, 19.7% are Protestant, 14% is Catholic while 14.8% are other Christians. This is followed by Islam (13.3%), traditional religions (0.2%), other religions (0.7%), and people who don't reside with any religion (4.1%).[5]

Economy

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2025) |

Obuasi is known for the Obuasi Gold Mine, one of the largest underground gold mines in the world. It is operated by AngloGold Ashanti. Gold has been mined on the site since the late 19th century.[6] Most of the production at the mine stopped in 2014 after being placed under care and maintenance. In 2018, a redevelopment project began to help increase production at the site. It is currently in its 3rd phase and was expected to be completed by late-2024.[8] Other major economic sectors in the town include timber, blacksmithing, and small-scale agriculture.[5]

Transportation

[edit]Obuasi train station is on the Ashanti railway line to and from Kumasi (59.4 km (36.9 mi) or 1 hour 2 minutes south-west of Kumasi).[5] The only airport in the town is the Obuasi Airport. It has a runway length of 1,600 by 30 m (5,249 by 98 ft) and was developed from a former airstrip. It was inaugurated on 30 August 2012 and is operated by Gianair on behalf of the owners.[9]

Geography

[edit]

Location

[edit]Obuasi is located in the Obuasi Municipal which has a total land mass of 220.7 km2 (85.2 sq mi). The municipal is bordered by Adansi South to the south, Amansie West to the west and northwest, and to the east and northeast, Adansi North.[5]

Climate

[edit]Obuasi has a semi-equatorial tropical savanna climate (Köppen climate classification Aw) with two rainy seasons. The main rainy season is from March to July, with May and June being typically the year's wettest months, whilst a lighter rainy season occurs from September to November. The average annual rainfall in Obuasi is around 1,270 millimetres or 50 inches and the average temperature 26.5 °C or 79.7 °F with highs of 30 °C or 86 °F and lows of 23 °C or 73.4 °F. Relative humidity is around 75% - 80% in the wet seasons.

| Climate data for Obuasi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 32 (89) |

31 (87) |

31 (87) |

31 (87) |

32 (89) |

29 (84) |

27 (80) |

27 (80) |

26 (79) |

30 (86) |

32 (89) |

32 (89) |

30 (86) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24 (75) |

24 (76) |

24 (76) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

22 (71) |

21 (70) |

24 (75) |

24 (76) |

24 (76) |

24 (75) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 25 (1.0) |

25 (1.0) |

76 (3.0) |

130 (5.0) |

200 (8.0) |

230 (9.0) |

100 (4.0) |

25 (1.0) |

76 (3.0) |

150 (6.0) |

130 (5.0) |

100 (4.0) |

1,267 (50) |

| Source: Myweather2.com[10] | |||||||||||||

Human resources

[edit]Education

[edit]Obuasi is the site of Obuasi Senior High Technical School, a coeducational second cycle public high school.[11] Christ the King Catholic Senior High School, St. Margaret Senior High School, and the College of Integrated Health Care are other schools that can be found in the town. Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology also has a campus in the town.[12]

Health

[edit]The town is home to numerus healthcare facilities, such as the AGA Hospital, owned and operated by AngloGold Ashanti, and St. Jude Hospital,[13] owned by Dr George Owusu-Asiedu.[14]

Sports

[edit]

Obuasi has a golf course,[15] which hosts the annual Obuasi Captain's Golf Tournament.[16] The Ashanti Gold Sporting Club, a professional football club, is located in the town and is based at Len Clay Stadium.[17]

Notable people

[edit]- Sam E. Jonah (KBE) (born 1949), the former CEO of Ashanti Goldfields Company[18]

- Jonathan Mensah (born 1982), Ghanaian footballer[19]

- John Mensah (born 1990), Ghanaian footballer.[20]

Sister cities

[edit]Obuasi sister cities is of the following:[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "World Gazetteer online". World-gazetteer.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Agyeman, Adwoa (22 January 2019). "Akufo-Addo reopens Obuasi gold mine". Adomonline.com. Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "An Economic History of the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation" (PDF) (PDF). Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Elijah Adansi-Bonah unanimously confirmed as MCE for Obuasi". citinewsroom.com. 29 September 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e 2010 Population & Housing census (Obuasi Municipal) (PDF) (Report). Ghana Statistical Service. 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ a b Andres, C. (7 August 2013). "World's top 10 gold deposits". Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Obuasi". Britannica. 8 January 2015. Archived from the original on 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Obuasi, Ghana". AngloGold Ashanti. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "AngloGold's $4m airport inaugurated". Ghana Business News. 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Obuasi Weather Averages". Myweather2. 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- ^ "Obuasi Sec-Tech old students support alma mater". Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Home | Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology". www.knust.edu.gh. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "St. Jude Hospital Obuasi - Obuasi - WorldPlaces". ghana.worldplaces.me. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- ^ "Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine" (PDF) (PDF). May 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Obuasi Golf Course Photos". Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Obuasi Golf Club institutes academy for kids in catchment area - MyJoyOnline". myjoyonline.com. MyJoyOnline. 10 March 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "Ashanti Gold Sporting Club". Archived from the original on 1 December 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Directors: Sir Samuel Esson Jonah, KBE, OSG, Executive Chairman". Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Jonathan Mensah set to captain Ghana against Congo". Pulse.com.gh. 5 September 2017. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ "Interview with John Mensah". 24 September 2007. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Riverside's Sister Cities". City of Riverside, California. 2009. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2009.

External links

[edit]- Official website

Obuasi travel guide from Wikivoyage

Obuasi travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Obuasi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Obuasi at Wikimedia Commons

Obuasi

View on GrokipediaObuasi is a city in the Ashanti Region of Ghana, approximately 60 kilometers south of Kumasi, serving as the administrative capital of the Obuasi Municipal District and defined primarily by its central role in gold mining. [1][2]

The city's economy revolves around the Obuasi Gold Mine, an underground operation reaching depths of 1,500 meters that has produced gold since 1897 and remains one of Africa's most significant mining assets following a major redevelopment completed in phases through 2024, enabling sustained commercial production at capacities up to 5,000 tons per day. [1][3]

While the mine has driven economic development and infrastructure growth in the region, including contributions to local employment and national gold output, it has also been associated with environmental challenges such as pollution affecting nearby communities. [4][5] The municipal district, covering 162.4 square kilometers with 55 communities, recorded a population of 168,641 in the 2010 census, reflecting its status as a key urban center in southern Ghana. [6][7]