Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

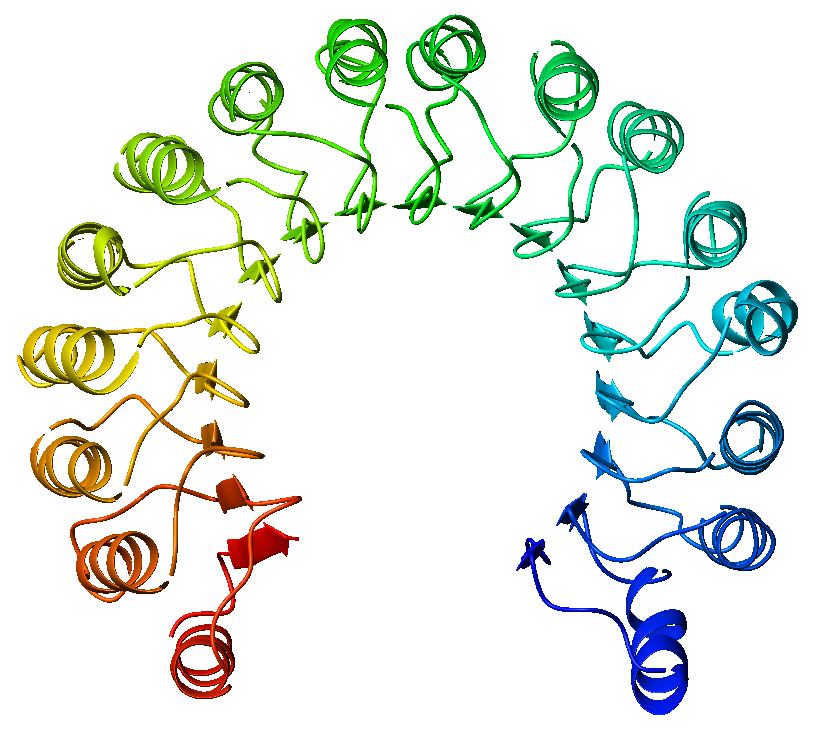

Leucine-rich repeat

View on Wikipedia An example of a leucine-rich repeat protein, a porcine ribonuclease inhibitor | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | LRR_1 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00560 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0022 | ||||||||

| ECOD | 207.1.1 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001611 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 2bnh / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| Membranome | 605 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Leucine rich repeat variant | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a leucine-rich repeat variant with a novel repetitive protein structural motif | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | LRV | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01816 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0020 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR004830 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1lrv / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| Membranome | 737 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| LRR adjacent | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

internalin h: crystal structure of fused n-terminal domains. | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | LRR_adjacent | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08191 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR012569 | ||||||||

| Membranome | 341 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Leucine rich repeat N-terminal domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

dimeric bovine tissue-extracted decorin, crystal form 2 | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | LRRNT | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01462 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000372 | ||||||||

| SMART | LRRNT | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1m10 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| Membranome | 127 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Leucine rich repeat N-terminal domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

the crystal structure of pgip (polygalacturonase inhibiting protein), a leucine rich repeat protein involved in plant defense | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | LRRNT_2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08263 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013210 | ||||||||

| SMART | LRRNT | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1m10 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Leucine rich repeat C-terminal domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

third lrr domain of drosophila slit | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | LRRCT | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01463 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000483 | ||||||||

| SMART | LRRCT | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1m10 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| LRV protein FeS4 cluster | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a leucine-rich repeat variant with a novel repetitive protein structural motif | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | LRV_FeS | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF05484 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0020 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR008665 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1lrv / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

A leucine-rich repeat (LRR) is a protein structural motif that forms an α/β horseshoe fold.[1][2] It is composed of repeating 20–30 amino acid stretches that are unusually rich in the hydrophobic amino acid leucine. These tandem repeats commonly fold together to form a solenoid protein domain, termed leucine-rich repeat domain. Typically, each repeat unit has beta strand-turn-alpha helix structure, and the assembled domain, composed of many such repeats, has a horseshoe shape with an interior parallel beta sheet and an exterior array of helices. One face of the beta sheet and one side of the helix array are exposed to solvent and are therefore dominated by hydrophilic residues. The region between the helices and sheets is the protein's hydrophobic core and is tightly sterically packed with leucine residues.

Leucine-rich repeats are frequently involved in the formation of protein–protein interactions.[3][4]

Examples

[edit]Leucine-rich repeat motifs have been identified in a large number of functionally unrelated proteins.[5] The best-known example is the ribonuclease inhibitor, but other proteins such as the tropomyosin regulator tropomodulin and the toll-like receptor also share the motif. In fact, the toll-like receptor possesses 10 successive LRR motifs which serve to bind pathogen- and danger-associated molecular patterns.

Although the canonical LRR protein contains approximately one helix for every beta strand, variants that form beta-alpha superhelix folds sometimes have long loops rather than helices linking successive beta strands.

One leucine-rich repeat variant domain (LRV) has a novel repetitive structural motif consisting of alternating alpha- and 310-helices arranged in a right-handed superhelix, with the absence of the beta-sheets present in other leucine-rich repeats.[6]

Associated domains

[edit]Leucine-rich repeats are often flanked by N-terminal and C-terminal cysteine-rich domains, but not always as is the case with C5orf36

They also co-occur with LRR adjacent domains. These are small, all beta strand domains, which have been structurally described for the protein Internalin (InlA) and related proteins InlB, InlE, InlH from the pathogenic bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. Their function appears to be mainly structural: They are fused to the C-terminal end of leucine-rich repeats, significantly stabilising the LRR, and forming a common rigid entity with the LRR. They are themselves not involved in protein-protein-interactions but help to present the adjacent LRR-domain for this purpose. These domains belong to the family of Ig-like domains in that they consist of two sandwiched beta sheets that follow the classical connectivity of Ig-domains. The beta strands in one of the sheets is, however, much smaller than in most standard Ig-like domains, making it somewhat of an outlier.[7][8][9]

An iron sulphur cluster is found at the N-terminus of some proteins containing the leucine-rich repeat variant domain (LRV). These proteins have a two-domain structure, composed of a small N-terminal domain containing a cluster of four Cysteine residues that houses the 4Fe:4S cluster, and a larger C-terminal domain containing the LRV repeats.[6] Biochemical studies revealed that the 4Fe:4S cluster is sensitive to oxygen, but does not appear to have reversible redox activity.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kobe B, Deisenhofer J (October 1994). "The leucine-rich repeat: a versatile binding motif". Trends Biochem. Sci. 19 (10): 415–21. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(94)90090-6. PMID 7817399.

- ^ Enkhbayar P, Kamiya M, Osaki M, Matsumoto T, Matsushima N (February 2004). "Structural principles of leucine-rich repeat (LRR) proteins". Proteins. 54 (3): 394–403. doi:10.1002/prot.10605. PMID 14747988. S2CID 19951452.

- ^ Kobe B, Kajava AV (December 2001). "The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11 (6): 725–32. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(01)00266-4. PMID 11751054.

- ^ Gay NJ, Packman LC, Weldon MA, Barna JC (October 1991). "A leucine-rich repeat peptide derived from the Drosophila Toll receptor forms extended filaments with a beta-sheet structure". FEBS Lett. 291 (1): 87–91. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(91)81110-T. PMID 1657640. S2CID 84294221.

- ^ Rothberg JM, Jacobs JR, Goodman CS, Artavanis-Tsakonas S (December 1990). "slit: an extracellular protein necessary for development of midline glia and commissural axon pathways contains both EGF and LRR domains". Genes Dev. 4 (12A): 2169–87. doi:10.1101/gad.4.12a.2169. PMID 2176636.

- ^ a b Peters JW, Stowell MH, Rees DC (December 1996). "A leucine-rich repeat variant with a novel repetitive protein structural motif". Nat. Struct. Biol. 3 (12): 991–4. doi:10.1038/nsb1296-991. PMID 8946850. S2CID 36535731.

- ^ Schubert WD, Gobel G, Diepholz M, Darji A, Kloer D, Hain T, Chakraborty T, Wehland J, Domann E, Heinz DW (September 2001). "Internalins from the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes combine three distinct folds into a contiguous internalin domain". J. Mol. Biol. 312 (4): 783–94. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2001.4989. PMID 11575932.

- ^ Schubert WD, Urbanke C, Ziehm T, Beier V, Machner MP, Domann E, Wehland J, Chakraborty T, Heinz DW (December 2002). "Structure of internalin, a major invasion protein of Listeria monocytogenes, in complex with its human receptor E-cadherin". Cell. 111 (6): 825–36. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01136-4. PMID 12526809. S2CID 17232767.

- ^ Freiberg A, Machner MP, Pfeil W, Schubert WD, Heinz DW, Seckler R (March 2004). "Folding and stability of the leucine-rich repeat domain of internalin B from Listeri monocytogenes". J. Mol. Biol. 337 (2): 453–61. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.044. PMID 15003459.

Further reading

[edit]- Tooze, John; Brändén, Carl-Ivar (1999). Introduction to Protein Structure (2nd ed.). New York: Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8153-2305-0.

- Wei T, Gong J, Jamitzky F, Heckl WM, Stark RW, Roessle SC (November 2008). "LRRML: a conformational database and an XML description of leucine-rich repeats (LRRs)". BMC Struct. Biol. 8 (1): 47. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-8-47. PMC 2645405. PMID 18986514.