Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bacteria

View on Wikipedia

| Bacteria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scanning electron micrograph of Escherichia coli rods | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria Woese et al. 2024[2] |

| Type genus | |

| Bacillus Cohn 1872 (Approved Lists 1980)[7]

| |

| Kingdoms | |

|

And see text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Bacteria (/bækˈtɪəriə/ ⓘ; sg.: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and are present in most of its habitats. Bacteria inhabit the air, soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste, and the deep biosphere of Earth's crust. Bacteria play a vital role in many stages of the nutrient cycle by recycling nutrients and the fixation of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The nutrient cycle includes the decomposition of dead bodies; bacteria are responsible for the putrefaction stage in this process. In the biological communities surrounding hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, extremophile bacteria provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy. Bacteria also live in mutualistic, commensal and parasitic relationships with plants and animals. Most bacteria have not been characterised and there are many species that cannot be grown in the laboratory. The study of bacteria is known as bacteriology, a branch of microbiology.

Like all animals, humans carry vast numbers (approximately 1013 to 1014) of bacteria.[8] Most are in the gut, though there are many on the skin. Most of the bacteria in and on the body are harmless or rendered so by the protective effects of the immune system, and many are beneficial,[9] particularly the ones in the gut. However, several species of bacteria are pathogenic and cause infectious diseases, including cholera, syphilis, anthrax, leprosy, tuberculosis, tetanus and bubonic plague. The most common fatal bacterial diseases are respiratory infections. Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections and are also used in farming, making antibiotic resistance a growing problem. Bacteria are important in sewage treatment and the breakdown of oil spills, the production of cheese and yogurt through fermentation, the recovery of gold, palladium, copper and other metals in the mining sector (biomining, bioleaching), as well as in biotechnology, and the manufacture of antibiotics and other chemicals.

Once regarded as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes ("fission fungi"), bacteria are now classified as prokaryotes. Unlike cells of animals and other eukaryotes, bacterial cells contain circular chromosomes, do not contain a nucleus and rarely harbour membrane-bound organelles. Although the term bacteria traditionally included all prokaryotes, the scientific classification changed after the discovery in the 1990s that prokaryotes consist of two very different groups of organisms that evolved from an ancient common ancestor. These evolutionary domains are called Bacteria and Archaea.[10] Unlike Archaea, bacteria contain ester-linked lipids in the cell membrane,[11] possess elongation factors that are resistant to ADP-ribosylation by diphtheria toxin,[12] use formylmethionine in protein synthesis initiation,[13] and have numerous genetic differences, including a different 16S rRNA[citation needed].

Etymology

[edit]

The word bacteria is the plural of the Neo-Latin bacterium, which is the romanisation of the Ancient Greek βακτήριον (baktḗrion),[14] the diminutive of βακτηρία (baktēría), meaning 'staff' or 'cane',[15] because the first ones to be discovered were rod-shaped.[16][17]

Knowledge of bacteria

[edit]Although an estimated 43,000 species of bacteria have been named, most of them have never been studied.[18] In fact, just 10 bacterial species account for half of all publications, whereas nearly 75% of all named bacteria have no academic research devoted to them.[18] The best-studied species, Escherichia coli, has more than 300,000 studies published on it,[18] but many of these papers likely use it only as a cloning vehicle to study other species, without providing any insight into its own biology. 90% of scientific studies on bacteria focus on less than 1% of species, mostly pathogenic bacteria relevant to human health.[18][19]

While E. coli is probably the best-studied bacterium, a quarter of its 4000 genes are poorly studied or remain uncharacterized. Some bacteria with minimal genomes (< 600 genes, e.g. Mycoplasma) usually have a large fraction of their genes functionally characterized, given that most of them are essential and conserved in many other species.[20]

Origin and early evolution

[edit]

The ancestors of bacteria were unicellular microorganisms that were the first forms of life to appear on Earth, about 4 billion years ago.[22] For about 3 billion years, most organisms were microscopic, and bacteria and archaea were the dominant forms of life.[23][24][25] Although bacterial fossils exist, such as stromatolites, their lack of distinctive morphology prevents them from being used to examine the history of bacterial evolution, or to date the time of origin of a particular bacterial species. However, gene sequences can be used to reconstruct the bacterial phylogeny, and these studies indicate that bacteria diverged first from the archaeal/eukaryotic lineage.[26] The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of bacteria and archaea was probably a hyperthermophile that lived about 2.5 billion–3.2 billion years ago.[27][28][29] The earliest life on land may have been bacteria some 3.22 billion years ago.[30]

Bacteria were also involved in the second great evolutionary divergence, that of the archaea and eukaryotes.[31][32] Here, eukaryotes resulted from the entering of ancient bacteria into endosymbiotic associations with the ancestors of eukaryotic cells, which were themselves possibly related to the Archaea.[33][34] This involved the engulfment by proto-eukaryotic cells of alphaproteobacterial symbionts to form either mitochondria or hydrogenosomes, which are still found in all known Eukarya (sometimes in highly reduced form, e.g. in ancient "amitochondrial" protozoa). Later, some eukaryotes that already contained mitochondria also engulfed cyanobacteria-like organisms, leading to the formation of chloroplasts in algae and plants. This is known as primary endosymbiosis.[35]

Habitat

[edit]Bacteria are ubiquitous, living in every possible habitat on the planet including soil, underwater, deep in Earth's crust and even such extreme environments as acidic hot springs and radioactive waste.[36][37] There are thought to be approximately 2×1030 bacteria on Earth,[38] forming a biomass that is only exceeded by plants.[39] They are abundant in lakes and oceans, in arctic ice, and geothermal springs[40] where they provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy.[41] They live on and in plants and animals. Most do not cause diseases, are beneficial to their environments, and are essential for life.[9][42] The soil is a rich source of bacteria and a few grams contain around a thousand million of them. They are all essential to soil ecology, breaking down toxic waste and recycling nutrients. They are even found in the atmosphere and one cubic metre of air holds around one hundred million bacterial cells. The oceans and seas harbour around 3 x 1026 bacteria which provide up to 50% of the oxygen humans breathe.[43] Only around 2% of bacterial species have been fully studied.[44]

| Habitat | Species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cold (minus 15 °C Antarctica) | Cryptoendoliths | [45] |

| Hot (70–121 °C): geysers, Submarine hydrothermal vents, oceanic crust | Thermus aquaticus, Pyrolobus fumarii, Pyrococcus furiosus | [46][44][47] |

| Radiation, 5MRad | Deinococcus radiodurans | [45] |

| Saline, 47% salt (Dead Sea, Great Salt Lake) | several species | [44][45] |

| Acid pH 3 | several species | [36] |

| Alkaline pH 12.8 | betaproteobacteria | [45] |

| Space (6 years on a NASA satellite) | Bacillus subtilis | [45] |

| 3.2 km underground | several species | [45] |

| High pressure (Mariana Trench – 1200 atm) | Moritella, Shewanella and others | [45] |

Morphology

[edit]

Size. Bacteria display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes. Bacterial cells are about one-tenth the size of eukaryotic cells and are typically 0.5–5.0 micrometres in length. However, a few species are visible to the unaided eye—for example, Thiomargarita namibiensis is up to half a millimetre long,[48] Epulopiscium fishelsoni reaches 0.7 mm,[49] and Thiomargarita magnifica can reach even 2 cm in length, which is 50 times larger than other known bacteria.[50][51] Among the smallest bacteria are members of the genus Mycoplasma, which measure only 0.3 micrometres, as small as the largest viruses.[52] Some bacteria may be even smaller, but these ultramicrobacteria are not well-studied.[53]

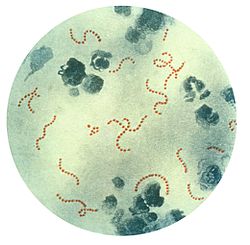

Shape. Most bacterial species are either spherical, called cocci (singular coccus, from Greek kókkos, grain, seed), or rod-shaped, called bacilli (sing. bacillus, from Latin baculus, stick).[54] Some bacteria, called vibrio, are shaped like slightly curved rods or comma-shaped; others can be spiral-shaped, called spirilla, or tightly coiled, called spirochaetes. A small number of other unusual shapes have been described, such as star-shaped bacteria.[55] This wide variety of shapes is determined by the bacterial cell wall and cytoskeleton and is important because it can influence the ability of bacteria to acquire nutrients, attach to surfaces, swim through liquids and escape predators.[56][57]

Multicellularity. Most bacterial species exist as single cells; others associate in characteristic patterns: Neisseria forms diploids (pairs), streptococci form chains, and staphylococci group together in "bunch of grapes" clusters. Bacteria can also group to form larger multicellular structures, such as the elongated filaments of Actinomycetota species, the aggregates of Myxobacteria species, and the complex hyphae of Streptomyces species.[59] These multicellular structures are often only seen in certain conditions. For example, when starved of amino acids, myxobacteria detect surrounding cells in a process known as quorum sensing, migrate towards each other, and aggregate to form fruiting bodies up to 500 micrometres long and containing approximately 100,000 bacterial cells.[60] In these fruiting bodies, the bacteria perform separate tasks; for example, about one in ten cells migrate to the top of a fruiting body and differentiate into a specialised dormant state called a myxospore, which is more resistant to drying and other adverse environmental conditions.[61]

Biofilms. Bacteria often attach to surfaces and form dense aggregations called biofilms[62] and larger formations known as microbial mats.[63] These biofilms and mats can range from a few micrometres in thickness to up to half a metre in depth, and may contain multiple species of bacteria, protists and archaea. Bacteria living in biofilms display a complex arrangement of cells and extracellular components, forming secondary structures, such as microcolonies, through which there are networks of channels to enable better diffusion of nutrients.[64][65] In natural environments, such as soil or the surfaces of plants, the majority of bacteria are bound to surfaces in biofilms.[66] Biofilms are also important in medicine, as these structures are often present during chronic bacterial infections or in infections of implanted medical devices, and bacteria protected within biofilms are much harder to kill than individual isolated bacteria.[67]

Cellular structure

[edit]

Intracellular structures

[edit]The bacterial cell is surrounded by a cell membrane, which is made primarily of phospholipids. This membrane encloses the contents of the cell and acts as a barrier to hold nutrients, proteins and other essential components of the cytoplasm within the cell.[68] Unlike eukaryotic cells, bacteria usually lack large membrane-bound structures in their cytoplasm such as a nucleus, mitochondria, chloroplasts and the other organelles present in eukaryotic cells.[69] However, some bacteria have protein-bound organelles in the cytoplasm which compartmentalise aspects of bacterial metabolism,[70][71] such as the carboxysome.[72] Additionally, bacteria have a multi-component cytoskeleton to control the localisation of proteins and nucleic acids within the cell, and to manage the process of cell division.[73][74][75]

Many important biochemical reactions, such as energy generation, occur due to concentration gradients across membranes, creating a potential difference analogous to a battery. The general lack of internal membranes in bacteria means these reactions, such as electron transport, occur across the cell membrane between the cytoplasm and the outside of the cell or periplasm.[76] However, in many photosynthetic bacteria, the plasma membrane is highly folded and fills most of the cell with layers of light-gathering membrane.[77] These light-gathering complexes may even form lipid-enclosed structures called chlorosomes in green sulfur bacteria.[78]

Bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and their genetic material is typically a single circular bacterial chromosome of DNA located in the cytoplasm in an irregularly shaped body called the nucleoid.[79] The nucleoid contains the chromosome with its associated proteins and RNA. Like all other organisms, bacteria contain ribosomes for the production of proteins, but the structure of the bacterial ribosome is different from that of eukaryotes and archaea.[80]

Some bacteria produce intracellular nutrient storage granules, such as glycogen,[81] polyphosphate,[82] sulfur[83] or polyhydroxyalkanoates.[84] Bacteria such as the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, produce internal gas vacuoles, which they use to regulate their buoyancy, allowing them to move up or down into water layers with different light intensities and nutrient levels.[85]

Extracellular structures

[edit]Around the outside of the cell membrane is the cell wall. Bacterial cell walls are made of peptidoglycan (also called murein), which is made from polysaccharide chains cross-linked by peptides containing D-amino acids.[86] Bacterial cell walls are different from the cell walls of plants and fungi, which are made of cellulose and chitin, respectively.[87] The cell wall of bacteria is also distinct from that of archaea, which do not contain peptidoglycan. The cell wall is essential to the survival of many bacteria, and the antibiotic penicillin (produced by a fungus called Penicillium) is able to kill bacteria by inhibiting a step in the synthesis of peptidoglycan.[87]

There are broadly speaking two different types of cell wall in bacteria, that classify bacteria into Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria. The names originate from the reaction of cells to the Gram stain, a long-standing test for the classification of bacterial species.[88]

Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick cell wall containing many layers of peptidoglycan and teichoic acids. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall consisting of a few layers of peptidoglycan surrounded by a second lipid membrane containing lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins. Most bacteria have the Gram-negative cell wall, and only members of the Bacillota group and actinomycetota (previously known as the low G+C and high G+C Gram-positive bacteria, respectively) have the alternative Gram-positive arrangement.[89] These differences in structure can produce differences in antibiotic susceptibility; for instance, vancomycin can kill only Gram-positive bacteria and is ineffective against Gram-negative pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[90] Some bacteria have cell wall structures that are neither classically Gram-positive or Gram-negative. This includes clinically important bacteria such as mycobacteria which have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall like a Gram-positive bacterium, but also a second outer layer of lipids.[91]

In many bacteria, an S-layer of rigidly arrayed protein molecules covers the outside of the cell.[92] This layer provides chemical and physical protection for the cell surface and can act as a macromolecular diffusion barrier. S-layers have diverse functions and are known to act as virulence factors in Campylobacter species and contain surface enzymes in Bacillus stearothermophilus.[93][94]

Flagella are rigid protein structures, about 20 nanometres in diameter and up to 20 micrometres in length, that are used for motility. Flagella are driven by the energy released by the transfer of ions down an electrochemical gradient across the cell membrane.[95]

Fimbriae (sometimes called "attachment pili") are fine filaments of protein, usually 2–10 nanometres in diameter and up to several micrometres in length. They are distributed over the surface of the cell, and resemble fine hairs when seen under the electron microscope.[96] Fimbriae are believed to be involved in attachment to solid surfaces or to other cells, and are essential for the virulence of some bacterial pathogens.[97] Pili (sing. pilus) are cellular appendages, slightly larger than fimbriae, that can transfer genetic material between bacterial cells in a process called conjugation where they are called conjugation pili or sex pili (see bacterial genetics, below).[98] They can also generate movement where they are called type IV pili.[99]

Glycocalyx is produced by many bacteria to surround their cells,[100] and varies in structural complexity: ranging from a disorganised slime layer of extracellular polymeric substances to a highly structured capsule. These structures can protect cells from engulfment by eukaryotic cells such as macrophages (part of the human immune system).[101] They can also act as antigens and be involved in cell recognition, as well as aiding attachment to surfaces and the formation of biofilms.[102]

The assembly of these extracellular structures is dependent on bacterial secretion systems. These transfer proteins from the cytoplasm into the periplasm or into the environment around the cell. Many types of secretion systems are known and these structures are often essential for the virulence of pathogens, so are intensively studied.[102]

Endospores

[edit]

Some genera of Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus, Clostridium, Sporohalobacter, Anaerobacter, and Heliobacterium, can form highly resistant, dormant structures called endospores.[104] Endospores develop within the cytoplasm of the cell; generally, a single endospore develops in each cell.[105] Each endospore contains a core of DNA and ribosomes surrounded by a cortex layer and protected by a multilayer rigid coat composed of peptidoglycan and a variety of proteins.[105]

Endospores show no detectable metabolism and can survive extreme physical and chemical stresses, such as high levels of UV light, gamma radiation, detergents, disinfectants, heat, freezing, pressure, and desiccation.[106] In this dormant state, these organisms may remain viable for millions of years.[107][108][109] Endospores even allow bacteria to survive exposure to the vacuum and radiation of outer space, leading to the possibility that bacteria could be distributed throughout the universe by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, planetoids, or directed panspermia.[110][111]

Endospore-forming bacteria can cause disease; for example, anthrax can be contracted by the inhalation of Bacillus anthracis endospores, and contamination of deep puncture wounds with Clostridium tetani endospores causes tetanus, which, like botulism, is caused by a toxin released by the bacteria that grow from the spores.[112] Clostridioides difficile infection, a common problem in healthcare settings, is caused by spore-forming bacteria.[113]

Metabolism

[edit]Bacteria exhibit an extremely wide variety of metabolic types.[114] The distribution of metabolic traits within a group of bacteria has traditionally been used to define their taxonomy, but these traits often do not correspond with modern genetic classifications.[115] Bacterial metabolism is classified into nutritional groups on the basis of three major criteria: the source of energy, the electron donors used, and the source of carbon used for growth.[116]

Phototrophic bacteria derive energy from light using photosynthesis, while chemotrophic bacteria breaking down chemical compounds through oxidation,[117] driving metabolism by transferring electrons from a given electron donor to a terminal electron acceptor in a redox reaction. Chemotrophs are further divided by the types of compounds they use to transfer electrons. Bacteria that derive electrons from inorganic compounds such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, or ammonia are called lithotrophs, while those that use organic compounds are called organotrophs.[117] Still, more specifically, aerobic organisms use oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor, while anaerobic organisms use other compounds such as nitrate, sulfate, or carbon dioxide.[117]

Many bacteria, called heterotrophs, derive their carbon from other organic carbon. Others, such as cyanobacteria and some purple bacteria, are autotrophic, meaning they obtain cellular carbon by fixing carbon dioxide.[118] In unusual circumstances, the gas methane can be used by methanotrophic bacteria as both a source of electrons and a substrate for carbon anabolism.[119]

| Nutritional type | Source of energy | Source of carbon | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phototrophs | Sunlight | Organic compounds (photoheterotrophs) or carbon fixation (photoautotrophs) | Cyanobacteria, Green sulfur bacteria, Chloroflexota, Purple bacteria |

| Lithotrophs | Inorganic compounds | Organic compounds (lithoheterotrophs) or carbon fixation (lithoautotrophs) | Thermodesulfobacteriota, Hydrogenophilaceae, Nitrospirota |

| Organotrophs | Organic compounds | Organic compounds (chemoheterotrophs) or carbon fixation (chemoautotrophs) | Bacillus, Clostridium, Enterobacteriaceae |

In many ways, bacterial metabolism provides traits that are useful for ecological stability and for human society. For example, diazotrophs have the ability to fix nitrogen gas using the enzyme nitrogenase.[120] This trait, which can be found in bacteria of most metabolic types listed above,[121] leads to the ecologically important processes of denitrification, sulfate reduction, and acetogenesis, respectively.[122] Bacterial metabolic processes are important drivers in biological responses to pollution; for example, sulfate-reducing bacteria are largely responsible for the production of the highly toxic forms of mercury (methyl- and dimethylmercury) in the environment.[123] Nonrespiratory anaerobes use fermentation to generate energy and reducing power, secreting metabolic by-products (such as ethanol in brewing) as waste. Facultative anaerobes can switch between fermentation and different terminal electron acceptors depending on the environmental conditions in which they find themselves.[124]

Reproduction and growth

[edit]

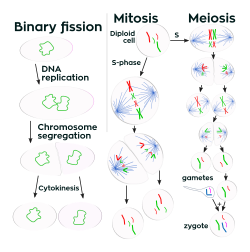

Unlike in multicellular organisms, increases in cell size (cell growth) and reproduction by cell division are tightly linked in unicellular organisms. Bacteria grow to a fixed size and then reproduce through binary fission, a form of asexual reproduction.[125] Under optimal conditions, bacteria can grow and divide extremely rapidly, and some bacterial populations can double as quickly as every 17 minutes.[126] In cell division, two identical clone daughter cells are produced. Some bacteria, while still reproducing asexually, form more complex reproductive structures that help disperse the newly formed daughter cells. Examples include fruiting body formation by myxobacteria and aerial hyphae formation by Streptomyces species, or budding. Budding involves a cell forming a protrusion that breaks away and produces a daughter cell.[127]

In the laboratory, bacteria are usually grown using solid or liquid media.[128] Solid growth media, such as agar plates, are used to isolate pure cultures of a bacterial strain. However, liquid growth media are used when the measurement of growth or large volumes of cells are required. Growth in stirred liquid media occurs as an even cell suspension, making the cultures easy to divide and transfer, although isolating single bacteria from liquid media is difficult. The use of selective media (media with specific nutrients added or deficient, or with antibiotics added) can help identify specific organisms.[129]

Most laboratory techniques for growing bacteria use high levels of nutrients to produce large amounts of cells cheaply and quickly.[128] However, in natural environments, nutrients are limited, meaning that bacteria cannot continue to reproduce indefinitely. This nutrient limitation has led the evolution of different growth strategies (see r/K selection theory). Some organisms can grow extremely rapidly when nutrients become available, such as the formation of algal and cyanobacterial blooms that often occur in lakes during the summer.[130] Other organisms have adaptations to harsh environments, such as the production of multiple antibiotics by Streptomyces that inhibit the growth of competing microorganisms.[131] In nature, many organisms live in communities (e.g., biofilms) that may allow for increased supply of nutrients and protection from environmental stresses.[66] These relationships can be essential for growth of a particular organism or group of organisms (syntrophy).[132]

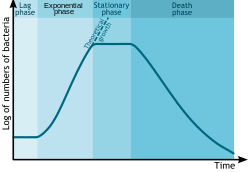

Bacterial growth follows four phases. When a population of bacteria first enter a high-nutrient environment that allows growth, the cells need to adapt to their new environment. The first phase of growth is the lag phase, a period of slow growth when the cells are adapting to the high-nutrient environment and preparing for fast growth. The lag phase has high biosynthesis rates, as proteins necessary for rapid growth are produced.[133][134] The second phase of growth is the logarithmic phase, also known as the exponential phase. The log phase is marked by rapid exponential growth. The rate at which cells grow during this phase is known as the growth rate (k), and the time it takes the cells to double is known as the generation time (g). During log phase, nutrients are metabolised at maximum speed until one of the nutrients is depleted and starts limiting growth. The third phase of growth is the stationary phase and is caused by depleted nutrients. The cells reduce their metabolic activity and consume non-essential cellular proteins. The stationary phase is a transition from rapid growth to a stress response state and there is increased expression of genes involved in DNA repair, antioxidant metabolism and nutrient transport.[135] The final phase is the death phase where the bacteria run out of nutrients and die.[136]

Genetics

[edit]

Most bacteria have a single circular chromosome that can range in size from only 160,000 base pairs in the endosymbiotic bacteria Carsonella ruddii,[138] to 12,200,000 base pairs (12.2 Mbp) in the soil-dwelling bacteria Sorangium cellulosum,[139] to 16.0 Mbp in another soil-dwelling bacteria, Minicystis rosea.[140] There are many exceptions to this; for example, some Streptomyces and Borrelia species contain a single linear chromosome,[141][142] while some bacteria including species of Vibrio contain more than one chromosome.[143][144] Some bacteria contain plasmids, small extra-chromosomal molecules of DNA that may contain genes for various useful functions such as antibiotic resistance, metabolic capabilities, or various virulence factors.[145]

Whether they have a single chromosome or more than one, almost all bacteria have a haploid genome. This means that they have only one copy of each gene encoding proteins. This is in contrast to eukaryotes, which are diploid or polyploid, meaning they have two or more copies of each gene. This means that unlike humans, who may still be able to create a protein if the gene becomes mutated (since the human genome has an extra copy in each cell), a bacterium will be completely unable to create the protein if its gene incurs an inactivating mutation.[146]

Bacterial genomes usually encode a few hundred to a few thousand genes. The genes in bacterial genomes are usually a single continuous stretch of DNA. Although several different types of introns do exist in bacteria, these are much rarer than in eukaryotes.[147]

Bacteria, as asexual organisms, inherit an identical copy of the parent's genome and are clonal. However, all bacteria can evolve by selection on changes to their genetic material DNA caused by genetic recombination or mutations. Mutations arise from errors made during the replication of DNA or from exposure to mutagens. Mutation rates vary widely among different species of bacteria and even among different clones of a single species of bacteria.[148] Genetic changes in bacterial genomes emerge from either random mutation during replication or "stress-directed mutation", where genes involved in a particular growth-limiting process have an increased mutation rate.[149]

Some bacteria transfer genetic material between cells. This can occur in three main ways. First, bacteria can take up exogenous DNA from their environment in a process called transformation.[150] Many bacteria can naturally take up DNA from the environment, while others must be chemically altered in order to induce them to take up DNA.[151] The development of competence in nature is usually associated with stressful environmental conditions and seems to be an adaptation for facilitating repair of DNA damage in recipient cells.[152] Second, bacteriophages can integrate into the bacterial chromosome, introducing foreign DNA in a process known as transduction. Many types of bacteriophage exist; some infect and lyse their host bacteria, while others insert into the bacterial chromosome.[153] Bacteria resist phage infection through restriction modification systems that degrade foreign DNA[154] and a system that uses CRISPR sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of phage that the bacteria have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block virus replication through a form of RNA interference.[155][156] Third, bacteria can transfer genetic material through direct cell contact via conjugation.[157]

In ordinary circumstances, transduction, conjugation, and transformation involve transfer of DNA between individual bacteria of the same species, but occasionally transfer may occur between individuals of different bacterial species, and this may have significant consequences, such as the transfer of antibiotic resistance.[158][159] In such cases, gene acquisition from other bacteria or the environment is called horizontal gene transfer and may be common under natural conditions.[160]

Behaviour

[edit]Movement

[edit]

Many bacteria are motile (able to move themselves) and do so using a variety of mechanisms. The best studied of these are flagella, long filaments that are turned by a motor at the base to generate propeller-like movement.[161] The bacterial flagellum is made of about 20 proteins, with approximately another 30 proteins required for its regulation and assembly.[161] The flagellum is a rotating structure driven by a reversible motor at the base that uses the electrochemical gradient across the membrane for power.[162]

Bacteria can use flagella in different ways to generate different kinds of movement. Many bacteria (such as E. coli) have two distinct modes of movement: forward movement (swimming) and tumbling. The tumbling allows them to reorient and makes their movement a three-dimensional random walk.[163] Bacterial species differ in the number and arrangement of flagella on their surface; some have a single flagellum (monotrichous), a flagellum at each end (amphitrichous), clusters of flagella at the poles of the cell (lophotrichous), while others have flagella distributed over the entire surface of the cell (peritrichous). The flagella of a group of bacteria, the spirochaetes, are found between two membranes in the periplasmic space. They have a distinctive helical body that twists about as it moves.[161]

Two other types of bacterial motion are called twitching motility that relies on a structure called the type IV pilus,[164] and gliding motility, that uses other mechanisms. In twitching motility, the rod-like pilus extends out from the cell, binds some substrate, and then retracts, pulling the cell forward.[165]

Motile bacteria are attracted or repelled by certain stimuli in behaviours called taxes: these include chemotaxis, phototaxis, energy taxis, and magnetotaxis.[166][167][168] In one peculiar group, the myxobacteria, individual bacteria move together to form waves of cells that then differentiate to form fruiting bodies containing spores.[61] The myxobacteria move only when on solid surfaces, unlike E. coli, which is motile in liquid or solid media.[169]

Several Listeria and Shigella species move inside host cells by usurping the cytoskeleton, which is normally used to move organelles inside the cell. By promoting actin polymerisation at one pole of their cells, they can form a kind of tail that pushes them through the host cell's cytoplasm.[170]

Communication

[edit]A few bacteria have chemical systems that generate light. This bioluminescence often occurs in bacteria that live in association with fish, and the light probably serves to attract fish or other large animals.[171]

Bacteria often function as multicellular aggregates known as biofilms, exchanging a variety of molecular signals for intercell communication and engaging in coordinated multicellular behaviour.[172][173]

The communal benefits of multicellular cooperation include a cellular division of labour, accessing resources that cannot effectively be used by single cells, collectively defending against antagonists, and optimising population survival by differentiating into distinct cell types.[172] For example, bacteria in biofilms can have more than five hundred times increased resistance to antibacterial agents than individual "planktonic" bacteria of the same species.[173]

One type of intercellular communication by a molecular signal is called quorum sensing, which serves the purpose of determining whether the local population density is sufficient to support investment in processes that are only successful if large numbers of similar organisms behave similarly, such as excreting digestive enzymes or emitting light.[174][175] Quorum sensing enables bacteria to coordinate gene expression and to produce, release, and detect autoinducers or pheromones that accumulate with the growth in cell population.[176]

Classification and identification

[edit]

Classification seeks to describe the diversity of bacterial species by naming and grouping organisms based on similarities. Bacteria can be classified on the basis of cell structure, cellular metabolism or on differences in cell components, such as DNA, fatty acids, pigments, antigens and quinones.[129] While these schemes allowed the identification and classification of bacterial strains, it was unclear whether these differences represented variation between distinct species or between strains of the same species. This uncertainty was due to the lack of distinctive structures in most bacteria, as well as lateral gene transfer between unrelated species.[178] Due to lateral gene transfer, some closely related bacteria can have very different morphologies and metabolisms. To overcome this uncertainty, modern bacterial classification emphasises molecular systematics, using genetic techniques such as guanine cytosine ratio determination, genome-genome hybridisation, as well as sequencing genes that have not undergone extensive lateral gene transfer, such as the rRNA gene.[179] Classification of bacteria is determined by publication in the International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology,[180] and Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology.[181] The International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology (ICSB) maintains international rules for the naming of bacteria and taxonomic categories and for the ranking of them in the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria.[182]

Historically, bacteria were considered a part of the Plantae, the plant kingdom, and were called "Schizomycetes" (fission-fungi).[183] For this reason, collective bacteria and other microorganisms in a host are often called "flora".[184] The term "bacteria" was traditionally applied to all microscopic, single-cell prokaryotes. However, molecular systematics showed prokaryotic life to consist of two separate domains, originally called Eubacteria and Archaebacteria, but now called Bacteria and Archaea that evolved independently from an ancient common ancestor.[10] The archaea and eukaryotes are more closely related to each other than either is to the bacteria. These two domains, along with Eukarya, are the basis of the three-domain system, which is currently the most widely used classification system in microbiology.[185] However, due to the relatively recent introduction of molecular systematics and a rapid increase in the number of genome sequences that are available, bacterial classification remains a changing and expanding field.[186][187] For example, Cavalier-Smith argued that the Archaea and Eukaryotes evolved from Gram-positive bacteria.[188]

The identification of bacteria in the laboratory is particularly relevant in medicine, where the correct treatment is determined by the bacterial species causing an infection. Consequently, the need to identify human pathogens was a major impetus for the development of techniques to identify bacteria.[189] Once a pathogenic organism has been isolated, it can be further characterised by its morphology, growth patterns (such as aerobic or anaerobic growth), patterns of hemolysis, and staining.[190]

Classification by staining

[edit]The Gram stain, developed in 1884 by Hans Christian Gram, characterises bacteria based on the structural characteristics of their cell walls.[191][88] The thick layers of peptidoglycan in the "Gram-positive" cell wall stain purple, while the thin "Gram-negative" cell wall appears pink.[191] By combining morphology and Gram-staining, most bacteria can be classified as belonging to one of four groups (Gram-positive cocci, Gram-positive bacilli, Gram-negative cocci and Gram-negative bacilli). Some organisms are best identified by stains other than the Gram stain, particularly mycobacteria or Nocardia, which show acid fastness on Ziehl–Neelsen or similar stains.[192]

Classification by culturing

[edit]Culture techniques are designed to promote the growth and identify particular bacteria while restricting the growth of the other bacteria in the sample.[193] Often these techniques are designed for specific specimens; for example, a sputum sample will be treated to identify organisms that cause pneumonia, while stool specimens are cultured on selective media to identify organisms that cause diarrhea while preventing growth of non-pathogenic bacteria. Specimens that are normally sterile, such as blood, urine or spinal fluid, are cultured under conditions designed to grow all possible organisms.[129][194] Other organisms may need to be identified by their growth in special media, or by other techniques, such as serology.[195]

Molecular classification

[edit]As with bacterial classification, identification of bacteria is increasingly using molecular methods,[196] and mass spectroscopy.[197] Most bacteria have not been characterised and there are many species that cannot be grown in the laboratory.[198] Diagnostics using DNA-based tools, such as polymerase chain reaction, are increasingly popular due to their specificity and speed, compared to culture-based methods.[199] These methods also allow the detection and identification of "viable but nonculturable" cells that are metabolically active but non-dividing.[200] The main way to characterize and classify these bacteria is to isolate their DNA from environmental samples and mass-sequence them. This approach has identified thousands, if not millions of candidate species. Based on some estimates, more than 43,000 species of bacteria have been described,[18] but attempts to estimate the true number of bacterial diversity have ranged from 107 to 109 total species—and even these diverse estimates may be off by many orders of magnitude.[201][202]

Phyla

[edit]Valid phyla

[edit]The following phyla have been validly published according to the Prokaryotic Code; phyla that do not belong to any kingdom are shown in bold:[203][7]

- Abditibacteriota

- Acidobacteriota

- Actinomycetota

- Aquificota

- Armatimonadota

- Atribacterota

- Bacillota

- Bacteroidota

- Balneolota

- Caldisericota

- Calditrichota

- Chlamydiota

- Chlorobiota

- Chloroflexota

- Chrysiogenota

- Coprothermobacterota

- Cyanobacteriota

- Deferribacterota

- Deinococcota

- Dictyoglomerota

- Elusimicrobiota

- Fibrobacterota

- Fidelibacterota

- Fusobacteriota

- Gemmatimonadota

- Kiritimatiellota

- Lentisphaerota

- Minisyncoccota

- Mycoplasmatota

- Nitrospinota

- Nitrospirota

- Planctomycetota

- Pseudomonadota

- Rhodothermota

- Spirochaetota

- Synergistota

- Thermodesulfobacteriota

- Thermomicrobiota

- Thermotogota

- Verrucomicrobiota

- Vulcanimicrobiota

Candidate phyla

[edit]The following phyla have been proposed, but have not been validly published according to the Prokaryotic Code; phyla that do not belong to any kingdom are shown in bold:[7][204]

- "Acetithermota"

- "Aerophobota"

- "Auribacterota"

- "Babelota"

- "Binatota"

- "Bipolaricaulota"

- "Caldipriscota"

- "Calescibacteriota"

- "Canglongiota"

- "Cloacimonadota"

- "Cosmopoliota"

- "Cryosericota"

- "Deferrimicrobiota"

- "Dormiibacterota"

- "Effluvivivacota"

- "Electryoneota"

- "Elulimicrobiota"

- "Fermentibacterota"

- "Fervidibacterota"

- "Goldiibacteriota"

- "Heilongiota"

- "Hinthialibacterota"

- "Hydrogenedentota"

- "Hydrothermota"

- "Kapaibacteriota"

- "Krumholzibacteriota"

- "Kryptoniota"

- "Latescibacterota"

- "Lernaellota"

- "Lithacetigenota"

- "Macinerneyibacteriota"

- "Margulisiibacteriota"

- "Methylomirabilota"

- "Moduliflexota"

- "Muiribacteriota"

- "Nitrosediminicolota"

- "Omnitrophota"

- "Parcunitrobacterota"

- "Peregrinibacteriota"

- "Qinglongiota"

- "Rifleibacteriota"

- "Ryujiniota"

- "Spongiamicota"

- "Sumerlaeota"

- "Sysuimicrobiota"

- "Tangaroaeota"

- "Tectimicrobiota"

- "Tianyaibacteriota"

- "Wirthibacterota"

- "Zhuqueibacterota"

- "Zhurongbacterota"

Interactions with other organisms

[edit]

Despite their apparent simplicity, bacteria can form complex associations with other organisms. These symbiotic associations can be divided into parasitism, mutualism and commensalism.[206]

Commensals

[edit]The word "commensalism" is derived from the word "commensal", meaning "eating at the same table"[207] and all plants and animals are colonised by commensal bacteria. In humans and other animals, trillions of them live on the skin, the airways, the gut and other orifices.[208][209] Referred to as "normal flora",[210] or "commensals",[211] these bacteria usually cause no harm but may occasionally invade other sites of the body and cause infection. Escherichia coli is a commensal in the human gut but can cause urinary tract infections.[212] Similarly, streptococci, which are part of the normal flora of the human mouth, can cause heart disease.[213]

Predators

[edit]Some species of bacteria kill and then consume other microorganisms; these species are called predatory bacteria.[214] These include organisms such as Myxococcus xanthus, which forms swarms of cells that kill and digest any bacteria they encounter.[215] Other bacterial predators either attach to their prey in order to digest them and absorb nutrients or invade another cell and multiply inside the cytosol.[216] These predatory bacteria are thought to have evolved from saprophages that consumed dead microorganisms, through adaptations that allowed them to entrap and kill other organisms.[217]

Mutualists

[edit]Certain bacteria form close spatial associations that are essential for their survival. One such mutualistic association, called interspecies hydrogen transfer, occurs between clusters of anaerobic bacteria that consume organic acids, such as butyric acid or propionic acid, and produce hydrogen, and methanogenic archaea that consume hydrogen.[218] The bacteria in this association are unable to consume the organic acids as this reaction produces hydrogen that accumulates in their surroundings. Only the intimate association with the hydrogen-consuming archaea keeps the hydrogen concentration low enough to allow the bacteria to grow.[219]

In soil, microorganisms that reside in the rhizosphere (a zone that includes the root surface and the soil that adheres to the root after gentle shaking) carry out nitrogen fixation, converting nitrogen gas to nitrogenous compounds.[220] This serves to provide an easily absorbable form of nitrogen for many plants, which cannot fix nitrogen themselves. Many other bacteria are found as symbionts in humans and other organisms. For example, the presence of over 1,000 bacterial species in the normal human gut flora of the intestines can contribute to gut immunity, synthesise vitamins, such as folic acid, vitamin K and biotin, convert sugars to lactic acid (see Lactobacillus), as well as fermenting complex undigestible carbohydrates.[221][222][223] The presence of this gut flora also inhibits the growth of potentially pathogenic bacteria (usually through competitive exclusion) and these beneficial bacteria are consequently sold as probiotic dietary supplements.[224]

Nearly all animal life is dependent on bacteria for survival as only bacteria and some archaea possess the genes and enzymes necessary to synthesise vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, and provide it through the food chain. Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin that is involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body. It is a cofactor in DNA synthesis and in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. It is particularly important in the normal functioning of the nervous system via its role in the synthesis of myelin.[225]

Pathogens

[edit]

The body is continually exposed to many species of bacteria, including beneficial commensals, which grow on the skin and mucous membranes, and saprophytes, which grow mainly in the soil and in decaying matter. The blood and tissue fluids contain nutrients sufficient to sustain the growth of many bacteria. The body has defence mechanisms that enable it to resist microbial invasion of its tissues and give it a natural immunity or innate resistance against many microorganisms.[226] Unlike some viruses, bacteria evolve relatively slowly so many bacterial diseases also occur in other animals.[227]

If bacteria form a parasitic association with other organisms, they are classed as pathogens.[228] Pathogenic bacteria are a major cause of human death and disease and cause infections such as tetanus (caused by Clostridium tetani), typhoid fever, diphtheria, syphilis, cholera, foodborne illness, leprosy (caused by Mycobacterium leprae) and tuberculosis (caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis).[229] A pathogenic cause for a known medical disease may only be discovered many years later, as was the case with Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease.[230] Bacterial diseases are also important in agriculture, and bacteria cause leaf spot, fire blight and wilts in plants, as well as Johne's disease, mastitis, salmonella and anthrax in farm animals.[231]

Each species of pathogen has a characteristic spectrum of interactions with its human hosts. Some organisms, such as Staphylococcus or Streptococcus, can cause skin infections, pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis, a systemic inflammatory response producing shock, massive vasodilation and death.[232] Yet these organisms are also part of the normal human flora and usually exist on the skin or in the nose without causing any disease at all. Other organisms invariably cause disease in humans, such as Rickettsia, which are obligate intracellular parasites able to grow and reproduce only within the cells of other organisms. One species of Rickettsia causes typhus, while another causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Chlamydia, another phylum of obligate intracellular parasites, contains species that can cause pneumonia or urinary tract infection and may be involved in coronary heart disease.[233] Some species, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cenocepacia, and Mycobacterium avium, are opportunistic pathogens and cause disease mainly in people who are immunosuppressed or have cystic fibrosis.[234][235] Some bacteria produce toxins, which cause diseases.[236] These are endotoxins, which come from broken bacterial cells, and exotoxins, which are produced by bacteria and released into the environment.[237] The bacterium Clostridium botulinum for example, produces a powerful exotoxin that cause respiratory paralysis, and Salmonellae produce an endotoxin that causes gastroenteritis.[237] Some exotoxins can be converted to toxoids, which are used as vaccines to prevent the disease.[238]

Bacterial infections may be treated with antibiotics, which are classified as bacteriocidal if they kill bacteria or bacteriostatic if they just prevent bacterial growth. There are many types of antibiotics, and each class inhibits a process that is different in the pathogen from that found in the host. An example of how antibiotics produce selective toxicity are chloramphenicol and puromycin, which inhibit the bacterial ribosome, but not the structurally different eukaryotic ribosome.[239] Antibiotics are used both in treating human disease and in intensive farming to promote animal growth, where they may be contributing to the rapid development of antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations.[240] Infections can be prevented by antiseptic measures such as sterilising the skin prior to piercing it with the needle of a syringe, and by proper care of indwelling catheters. Surgical and dental instruments are also sterilised to prevent contamination by bacteria. Disinfectants such as bleach are used to kill bacteria or other pathogens on surfaces to prevent contamination and further reduce the risk of infection.[241]

Significance in technology and industry

[edit]Bacteria, often lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus species and Lactococcus species, in combination with yeasts and moulds, have been used for thousands of years in the preparation of fermented foods, such as cheese, pickles, soy sauce, sauerkraut, vinegar, wine, and yogurt.[242][243]

The ability of bacteria to degrade a variety of organic compounds is remarkable and has been used in waste processing and bioremediation. Bacteria capable of digesting the hydrocarbons in petroleum are often used to clean up oil spills.[244] Fertiliser was added to some of the beaches in Prince William Sound in an attempt to promote the growth of these naturally occurring bacteria after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. These efforts were effective on beaches that were not too thickly covered in oil. Bacteria are also used for the bioremediation of industrial toxic wastes.[245] In the chemical industry, bacteria are most important in the production of enantiomerically pure chemicals for use as pharmaceuticals or agrichemicals.[246]

Bacteria can also be used in place of pesticides in biological pest control. This commonly involves Bacillus thuringiensis (also called BT), a Gram-positive, soil-dwelling bacterium. Subspecies of this bacteria are used as Lepidopteran-specific insecticides under trade names such as Dipel and Thuricide.[247] Because of their specificity, these pesticides are regarded as environmentally friendly, with little or no effect on humans, wildlife, pollinators, and most other beneficial insects.[248][249]

Because of their ability to quickly grow and the relative ease with which they can be manipulated, bacteria are the workhorses for the fields of molecular biology, genetics, and biochemistry. By making mutations in bacterial DNA and examining the resulting phenotypes, scientists can determine the function of genes, enzymes, and metabolic pathways in bacteria, then apply this knowledge to more complex organisms.[250] This aim of understanding the biochemistry of a cell reaches its most complex expression in the synthesis of huge amounts of enzyme kinetic and gene expression data into mathematical models of entire organisms. This is achievable in some well-studied bacteria, with models of Escherichia coli metabolism now being produced and tested.[251][252] This understanding of bacterial metabolism and genetics allows the use of biotechnology to bioengineer bacteria for the production of therapeutic proteins, such as insulin, growth factors, or antibodies.[253][254]

Because of their importance for research in general, samples of bacterial strains are isolated and preserved in Biological Resource Centres. This ensures the availability of the strain to scientists worldwide.[255]

History of bacteriology

[edit]

Bacteria were first observed by the Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676, using a single-lens microscope of his own design. Leeuwenhoek did not recognize bacteria as a distinct category of microorganisms, referring to all microorganisms that he observed, including bacteria, protists, and microscopic animals, as animalcules. He published his observations in a series of letters to the Royal Society of London.[256] Bacteria were Leeuwenhoek's most remarkable microscopic discovery. Their size was just at the limit of what his simple lenses could resolve, and, in one of the most striking hiatuses in the history of science, no one else would see them again for over a century.[257] His observations also included protozoans, and his findings were looked at again in the light of the more recent findings of cell theory.[258]

Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg introduced the word "bacterium" in 1828.[259] In fact, his Bacterium was a genus that contained non-spore-forming rod-shaped bacteria,[260] as opposed to Bacillus, a genus of spore-forming rod-shaped bacteria defined by Ehrenberg in 1835.[261]

Louis Pasteur demonstrated in 1859 that the growth of microorganisms causes the fermentation process and that this growth is not due to spontaneous generation (yeasts and molds, commonly associated with fermentation, are not bacteria, but rather fungi). Along with his contemporary Robert Koch, Pasteur was an early advocate of the germ theory of disease.[262] Before them, Ignaz Semmelweis and Joseph Lister had realised the importance of sanitised hands in medical work. Semmelweis, who in the 1840s formulated his rules for handwashing in the hospital, prior to the advent of germ theory, attributed disease to "decomposing animal organic matter". His ideas were rejected and his book on the topic condemned by the medical community. After Lister, however, doctors started sanitising their hands in the 1870s.[263]

Robert Koch, a pioneer in medical microbiology, worked on cholera, anthrax and tuberculosis. In his research into tuberculosis, Koch finally proved the germ theory, for which he received a Nobel Prize in 1905.[264] In Koch's postulates, he set out criteria to test if an organism is the cause of a disease, and these postulates are still used today.[265]

Ferdinand Cohn is said to be a founder of bacteriology, studying bacteria from 1870. Cohn was the first to classify bacteria based on their morphology.[266][267]

Though it was known in the nineteenth century that bacteria are the cause of many diseases, no effective antibacterial treatments were available.[268] In 1910, Paul Ehrlich developed the first antibiotic, by changing dyes that selectively stained Treponema pallidum—the spirochaete that causes syphilis—into compounds that selectively killed the pathogen.[269] Ehrlich, who had been awarded a 1908 Nobel Prize for his work on immunology, pioneered the use of stains to detect and identify bacteria, with his work being the basis of the Gram stain and the Ziehl–Neelsen stain.[270]

A major step forward in the study of bacteria came in 1977 when Carl Woese recognised that archaea have a separate line of evolutionary descent from bacteria.[271] This new phylogenetic taxonomy depended on the sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA and divided prokaryotes into two evolutionary domains, as part of the three-domain system.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "31. Ancient Life: Apex Chert Microfossils". www.lpi.usra.edu. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Göker M, Oren A (January 2024). "Valid publication of names of two domains and seven kingdoms of prokaryotes". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 74 (1). doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.006242. PMID 38252124. – this article represents the valid publication of the name Bacteria. Although Woese proposed the separation from Archaea in 1990, the name was not valid until this article from 2024, hence the date.

- ^ [Bacteria, not assigned to family] in LPSN; Parte AC, Sardà Carbasse J, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M (1 November 2020). "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 70 (11): 5607–5612. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004332.

- ^ [Microvibrio] in LPSN; Parte AC, Sardà Carbasse J, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M (1 November 2020). "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 70 (11): 5607–5612. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004332.

- ^ [Pedodermatophilus] in LPSN; Parte AC, Sardà Carbasse J, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M (1 November 2020). "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 70 (11): 5607–5612. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004332.

- ^ [Pelosigma] in LPSN; Parte AC, Sardà Carbasse J, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M (1 November 2020). "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 70 (11): 5607–5612. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004332.

- ^ a b c Parte AC, Sardà Carbasse J, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M (1 November 2020). "List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 70 (11): 5607–5612. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.004332. ISSN 1466-5026. PMC 7723251. PMID 32701423.

- ^ Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R (19 August 2016). "Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body". PLOS Biology. 14 (8) e1002533. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 4991899. PMID 27541692.

- ^ a b McCutcheon JP (October 2021). "The Genomics and Cell Biology of Host-Beneficial Intracellular Infections". Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 37 (1): 115–142. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-120219-024122. PMID 34242059. S2CID 235786110.

- ^ a b c Hall 2008, p. 145.

- ^ Santhosh PB, Genova J (28 December 2022). "Archaeosomes: New Generation of Liposomes Based on Archaeal Lipids for Drug Delivery and Biomedical Application". ACS Omega. 8 (1).

- ^ Kessel M, Klink F (18 September 1980). "Archaebacterial elongation factor is ADP-ribosylated by diphtheria toxin". Nature. PMID 6776409.

- ^ Falb M (2006). "Archaeal N-terminal Protein Maturation Commonly Involves N-terminal Acetylation: A Large-scale Proteomics Survey". Journal of Molecular Biology. 362 (5): 915–924.

- ^ βακτήριον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ βακτηρία in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ Harper D. "bacteria". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b Krasner 2014, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d e Jensen PA (4 January 2025). "Ten species comprise half of the bacteriology literature, leaving most species unstudied". bioRxiv 10.1101/2025.01.04.631297.

- ^ Callaway E (10 January 2025). "These are the 20 most-studied bacteria — the majority have been ignored". Nature. 637 (8047): 770–771. Bibcode:2025Natur.637..770C. doi:10.1038/d41586-025-00038-x. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 39794431.

- ^ Médigue C, Moszer I (December 2007). "Annotation, comparison and databases for hundreds of bacterial genomes". Research in Microbiology. 158 (10): 724–736. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2007.09.009. ISSN 0923-2508. PMID 18031997.

- ^ Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (June 1990). "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (12): 4576–79. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4576W. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMC 54159. PMID 2112744.

- ^ Hall 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Godoy-Vitorino F (July 2019). "Human microbial ecology and the rising new medicine". Annals of Translational Medicine. 7 (14): 342. doi:10.21037/atm.2019.06.56. PMC 6694241. PMID 31475212.

- ^ Schopf JW (July 1994). "Disparate rates, differing fates: tempo and mode of evolution changed from the Precambrian to the Phanerozoic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (15): 6735–42. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.6735S. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.15.6735. PMC 44277. PMID 8041691.

- ^ DeLong EF, Pace NR (August 2001). "Environmental diversity of bacteria and archaea". Systematic Biology. 50 (4): 470–78. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.321.8828. doi:10.1080/106351501750435040. PMID 12116647.

- ^ Brown JR, Doolittle WF (December 1997). "Archaea and the prokaryote-to-eukaryote transition". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 61 (4): 456–502. doi:10.1128/mmbr.61.4.456-502.1997. PMC 232621. PMID 9409149.

- ^ Daum B, Gold V (June 2018). "Twitch or swim: towards the understanding of prokaryotic motion based on the type IV pilus blueprint". Biological Chemistry. 399 (7): 799–808. doi:10.1515/hsz-2018-0157. hdl:10871/33366. PMID 29894297. S2CID 48352675.

- ^ Di Giulio M (December 2003). "The universal ancestor and the ancestor of bacteria were hyperthermophiles". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 57 (6): 721–30. Bibcode:2003JMolE..57..721D. doi:10.1007/s00239-003-2522-6. PMID 14745541. S2CID 7041325.

- ^ Battistuzzi FU, Feijao A, Hedges SB (November 2004). "A genomic timescale of prokaryote evolution: insights into the origin of methanogenesis, phototrophy, and the colonization of land". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 4 44. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-44. PMC 533871. PMID 15535883.

- ^ Homann M, Sansjofre P, Van Zuilen M, Heubeck C, Gong J, Killingsworth B, et al. (23 July 2018). "Microbial life and biogeochemical cycling on land 3,220 million years ago" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 11 (9): 665–671. Bibcode:2018NatGe..11..665H. doi:10.1038/s41561-018-0190-9. S2CID 134935568.

- ^ Gabaldón T (October 2021). "Origin and Early Evolution of the Eukaryotic Cell". Annual Review of Microbiology. 75 (1): 631–647. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062213. PMID 34343017. S2CID 236916203. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Callier V (8 June 2022). "Mitochondria and the origin of eukaryotes". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-060822-2. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Poole AM, Penny D (January 2007). "Evaluating hypotheses for the origin of eukaryotes". BioEssays. 29 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1002/bies.20516. PMID 17187354.

- ^ Dyall SD, Brown MT, Johnson PJ (April 2004). "Ancient invasions: from endosymbionts to organelles". Science. 304 (5668): 253–257. Bibcode:2004Sci...304..253D. doi:10.1126/science.1094884. PMID 15073369. S2CID 19424594.

- ^ Stephens TG, Gabr A, Calatrava V, Grossman AR, Bhattacharya D (September 2021). "Why is primary endosymbiosis so rare?". The New Phytologist. 231 (5): 1693–1699. Bibcode:2021NewPh.231.1693S. doi:10.1111/nph.17478. PMC 8711089. PMID 34018613.

- ^ a b Baker-Austin C, Dopson M (April 2007). "Life in acid: pH homeostasis in acidophiles". Trends in Microbiology. 15 (4): 165–171. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.005. PMID 17331729.

- ^ Jeong SW, Choi YJ (October 2020). "Extremophilic Microorganisms for the Treatment of Toxic Pollutants in the Environment". Molecules. 25 (21): 4916. doi:10.3390/molecules25214916. PMC 7660605. PMID 33114255.

- ^ Flemming HC, Wuertz S (April 2019). "Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 17 (4): 247–260. doi:10.1038/s41579-019-0158-9. PMID 30760902. S2CID 61155774.

- ^ Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R (June 2018). "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (25): 6506–6511. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790.

- ^ Wheelis 2008, p. 362.

- ^ Kushkevych I, Procházka J, Gajdács M, Rittmann SK, Vítězová M (June 2021). "Molecular Physiology of Anaerobic Phototrophic Purple and Green Sulfur Bacteria". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (12): 6398. doi:10.3390/ijms22126398. PMC 8232776. PMID 34203823.

- ^ Wheelis 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Pommerville 2014, p. 3–6.

- ^ a b c Krasner 2014, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pommerville 2014, p. 134.

- ^ Marion GM, Fritsen CH, Eicken H, Payne MC (December 2003). "The search for life on Europa: limiting environmental factors, potential habitats, and Earth analogues". Astrobiology. 3 (4): 785–811. Bibcode:2003AsBio...3..785M. doi:10.1089/153110703322736105. PMID 14987483.

- ^ Heuer VB, Inagaki F, Morono Y, Kubo Y, Spivack AJ, Viehweger B, et al. (December 2020). "Temperature limits to deep subseafloor life in the Nankai Trough subduction zone". Science. 370 (6521): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2020Sci...370.1230H. doi:10.1126/science.abd7934. hdl:2164/15700. PMID 33273103. S2CID 227257205.

- ^ Schulz HN, Jorgensen BB (2001). "Big bacteria". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55: 105–137. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.105. PMID 11544351. S2CID 18168018.

- ^ Williams C (2011). "Who are you calling simple?". New Scientist. 211 (2821): 38–41. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(11)61709-0.

- ^ Volland J, Gonzalez-Rizzo S, Gros O, Tyml T, Ivanova N, Schulz F, et al. (2022). "A centimeter-long bacterium with DNA contained in metabolically active, membrane-bound organelles". Science. 376 (6600): 1453–1458. Bibcode:2022Sci...376.1453V. doi:10.1126/science.abb3634. PMID 35737788.

- ^ Sanderson K (June 2022). "Largest bacterium ever found is surprisingly complex". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-01757-1. PMID 35750919. S2CID 250022076.

- ^ Robertson J, Gomersall M, Gill P (November 1975). "Mycoplasma hominis: growth, reproduction, and isolation of small viable cells". Journal of Bacteriology. 124 (2): 1007–1018. doi:10.1128/JB.124.2.1007-1018.1975. PMC 235991. PMID 1102522.

- ^ Velimirov B (2001). "Nanobacteria, Ultramicrobacteria and Starvation Forms: A Search for the Smallest Metabolizing Bacterium". Microbes and Environments. 16 (2): 67–77. doi:10.1264/jsme2.2001.67.

- ^ Dusenbery DB (2009). Living at Micro Scale. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 20–25. ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6.

- ^ Yang DC, Blair KM, Salama NR (March 2016). "Staying in Shape: the Impact of Cell Shape on Bacterial Survival in Diverse Environments". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 80 (1): 187–203. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00031-15. PMC 4771367. PMID 26864431.

- ^ Cabeen MT, Jacobs-Wagner C (August 2005). "Bacterial cell shape". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 3 (8): 601–10. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1205. PMID 16012516. S2CID 23938989.

- ^ Young KD (September 2006). "The selective value of bacterial shape". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 70 (3): 660–703. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00001-06. PMC 1594593. PMID 16959965.

- ^ Crawford 2007, p. xi.

- ^ Claessen D, Rozen DE, Kuipers OP, Søgaard-Andersen L, van Wezel GP (February 2014). "Bacterial solutions to multicellularity: a tale of biofilms, filaments and fruiting bodies". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 12 (2): 115–24. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3178. hdl:11370/0db66a9c-72ef-4e11-a75d-9d1e5827573d. PMID 24384602. S2CID 20154495.

- ^ Shimkets LJ (1999). "Intercellular signaling during fruiting-body development of Myxococcus xanthus". Annual Review of Microbiology. 53: 525–49. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.525. PMID 10547700.

- ^ a b Kaiser D (2004). "Signaling in myxobacteria". Annual Review of Microbiology. 58: 75–98. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123620. PMID 15487930.

- ^ Wheelis 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Mandal A, Dutta A, Das R, Mukherjee J (June 2021). "Role of intertidal microbial communities in carbon dioxide sequestration and pollutant removal: A review". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 170 112626. Bibcode:2021MarPB.17012626M. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112626. PMID 34153859.

- ^ Donlan RM (September 2002). "Biofilms: microbial life on surfaces". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (9): 881–90. doi:10.3201/eid0809.020063. PMC 2732559. PMID 12194761.

- ^ Branda SS, Vik S, Friedman L, Kolter R (January 2005). "Biofilms: the matrix revisited". Trends in Microbiology. 13 (1): 20–26. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.006. PMID 15639628.

- ^ a b Davey ME, O'toole GA (December 2000). "Microbial biofilms: from ecology to molecular genetics". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 64 (4): 847–67. doi:10.1128/MMBR.64.4.847-867.2000. PMC 99016. PMID 11104821.

- ^ Donlan RM, Costerton JW (April 2002). "Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 15 (2): 167–93. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. PMC 118068. PMID 11932229.

- ^ Slonczewski JL, Foster JW (2013). Microbiology: an Evolving Science (Third ed.). New York: W W Norton. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-393-12367-8.

- ^ Feijoo-Siota L, Rama JL, Sánchez-Pérez A, Villa TG (July 2017). "Considerations on bacterial nucleoids". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 101 (14): 5591–602. doi:10.1007/s00253-017-8381-7. PMID 28664324. S2CID 10173266.

- ^ Bobik TA (May 2006). "Polyhedral organelles compartmenting bacterial metabolic processes". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 70 (5): 517–25. doi:10.1007/s00253-005-0295-0. PMID 16525780. S2CID 8202321.

- ^ Yeates TO, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM (September 2008). "Protein-based organelles in bacteria: carboxysomes and related microcompartments". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 6 (9): 681–91. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1913. PMID 18679172. S2CID 22666203.

- ^ Kerfeld CA, Sawaya MR, Tanaka S, Nguyen CV, Phillips M, Beeby M, et al. (August 2005). "Protein structures forming the shell of primitive bacterial organelles". Science. 309 (5736): 936–38. Bibcode:2005Sci...309..936K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1026.896. doi:10.1126/science.1113397. PMID 16081736. S2CID 24561197.

- ^ Gitai Z (March 2005). "The new bacterial cell biology: moving parts and subcellular architecture". Cell. 120 (5): 577–86. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.026. PMID 15766522. S2CID 8894304.

- ^ Shih YL, Rothfield L (September 2006). "The bacterial cytoskeleton". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 70 (3): 729–54. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00017-06. PMC 1594594. PMID 16959967.

- ^ Norris V, den Blaauwen T, Cabin-Flaman A, Doi RH, Harshey R, Janniere L, et al. (March 2007). "Functional taxonomy of bacterial hyperstructures". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 71 (1): 230–53. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00035-06. PMC 1847379. PMID 17347523.

- ^ Pommerville 2014, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Bryant DA, Frigaard NU (November 2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends in Microbiology. 14 (11): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. PMID 16997562.

- ^ Psencík J, Ikonen TP, Laurinmäki P, Merckel MC, Butcher SJ, Serimaa RE, et al. (August 2004). "Lamellar organization of pigments in chlorosomes, the light harvesting complexes of green photosynthetic bacteria". Biophysical Journal. 87 (2): 1165–72. Bibcode:2004BpJ....87.1165P. doi:10.1529/biophysj.104.040956. PMC 1304455. PMID 15298919.

- ^ Thanbichler M, Wang SC, Shapiro L (October 2005). "The bacterial nucleoid: a highly organized and dynamic structure". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 96 (3): 506–21. doi:10.1002/jcb.20519. PMID 15988757. S2CID 25355087.

- ^ Poehlsgaard J, Douthwaite S (November 2005). "The bacterial ribosome as a target for antibiotics". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 3 (11): 870–81. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1265. PMID 16261170. S2CID 7521924.

- ^ Yeo M, Chater K (March 2005). "The interplay of glycogen metabolism and differentiation provides an insight into the developmental biology of Streptomyces coelicolor". Microbiology. 151 (Pt 3): 855–61. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27428-0. PMID 15758231. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ Shiba T, Tsutsumi K, Ishige K, Noguchi T (March 2000). "Inorganic polyphosphate and polyphosphate kinase: their novel biological functions and applications". Biochemistry. Biokhimiia. 65 (3): 315–23. PMID 10739474. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006.

- ^ Brune DC (June 1995). "Isolation and characterization of sulfur globule proteins from Chromatium vinosum and Thiocapsa roseopersicina". Archives of Microbiology. 163 (6): 391–99. Bibcode:1995ArMic.163..391B. doi:10.1007/BF00272127. PMID 7575095. S2CID 22279133.

- ^ Kadouri D, Jurkevitch E, Okon Y, Castro-Sowinski S (2005). "Ecological and agricultural significance of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 31 (2): 55–67. doi:10.1080/10408410590899228. PMID 15986831. S2CID 4098268.

- ^ Walsby AE (March 1994). "Gas vesicles". Microbiological Reviews. 58 (1): 94–144. doi:10.1128/MMBR.58.1.94-144.1994. PMC 372955. PMID 8177173.

- ^ van Heijenoort J (March 2001). "Formation of the glycan chains in the synthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan". Glycobiology. 11 (3): 25R – 36R. doi:10.1093/glycob/11.3.25R. PMID 11320055. S2CID 46066256.

- ^ a b Koch AL (October 2003). "Bacterial wall as target for attack: past, present, and future research". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (4): 673–87. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.4.673-687.2003. PMC 207114. PMID 14557293.

- ^ a b Gram HC (1884). "Über die isolierte Färbung der Schizomyceten in Schnitt- und Trockenpräparaten". Fortschr. Med. 2: 185–89.

- ^ Hugenholtz P (2002). "Exploring prokaryotic diversity in the genomic era". Genome Biology. 3 (2) REVIEWS0003. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-reviews0003. PMC 139013. PMID 11864374.

- ^ Walsh FM, Amyes SG (October 2004). "Microbiology and drug resistance mechanisms of fully resistant pathogens" (PDF). Current Opinion in Microbiology. 7 (5): 439–44. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2004.08.007. PMID 15451497.

- ^ Alderwick LJ, Harrison J, Lloyd GS, Birch HL (March 2015). "The Mycobacterial Cell Wall – Peptidoglycan and Arabinogalactan". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 5 (8) a021113. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021113. PMC 4526729. PMID 25818664.

- ^ Fagan RP, Fairweather NF (March 2014). "Biogenesis and functions of bacterial S-layers" (PDF). Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 12 (3): 211–22. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3213. PMID 24509785. S2CID 24112697.

- ^ Thompson SA (December 2002). "Campylobacter surface-layers (S-layers) and immune evasion". Annals of Periodontology. 7 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1902/annals.2002.7.1.43. PMC 2763180. PMID 16013216.

- ^ Beveridge TJ, Pouwels PH, Sára M, Kotiranta A, Lounatmaa K, Kari K, et al. (June 1997). "Functions of S-layers". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 20 (1–2): 99–149. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00305.x. PMID 9276929.

- ^ Kojima S, Blair DF (2004). The Bacterial Flagellar Motor: Structure and Function of a Complex Molecular Machine. International Review of Cytology. Vol. 233. pp. 93–134. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(04)33003-2. ISBN 978-0-12-364637-8. PMID 15037363.

- ^ Wheelis 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Cheng RA, Wiedmann M (2020). "Recent Advances in Our Understanding of the Diversity and Roles of Chaperone-Usher Fimbriae in Facilitating Salmonella Host and Tissue Tropism". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 10 628043. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.628043. PMC 7886704. PMID 33614531.

- ^ Silverman PM (February 1997). "Towards a structural biology of bacterial conjugation". Molecular Microbiology. 23 (3): 423–29. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2411604.x. PMID 9044277. S2CID 24126399.

- ^ Costa TR, Felisberto-Rodrigues C, Meir A, Prevost MS, Redzej A, Trokter M, et al. (June 2015). "Secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 13 (6): 343–59. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3456. PMID 25978706. S2CID 8664247.

- ^ Luong P, Dube DH (July 2021). "Dismantling the bacterial glycocalyx: Chemical tools to probe, perturb, and image bacterial glycans". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 42 116268. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116268. ISSN 0968-0896. PMC 8276522. PMID 34130219.

- ^ Stokes RW, Norris-Jones R, Brooks DE, Beveridge TJ, Doxsee D, Thorson LM (October 2004). "The glycan-rich outer layer of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis acts as an antiphagocytic capsule limiting the association of the bacterium with macrophages". Infection and Immunity. 72 (10): 5676–86. doi:10.1128/IAI.72.10.5676-5686.2004. PMC 517526. PMID 15385466.

- ^ a b Kalscheuer R, Palacios A, Anso I, Cifuente J, Anguita J, Jacobs WR, et al. (July 2019). "The Mycobacterium tuberculosis capsule: a cell structure with key implications in pathogenesis". The Biochemical Journal. 476 (14): 1995–2016. doi:10.1042/BCJ20190324. PMC 6698057. PMID 31320388.