Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

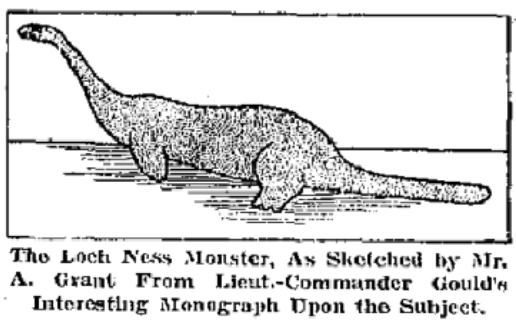

Lake monster

View on Wikipedia

A lake monster is a lake-dwelling creature in myth and folklore. The most famous example is the Loch Ness Monster. Depictions of lake monsters are often similar to those of sea monsters.

In the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature, entities classified as "lake monsters", such as the Scottish Loch Ness Monster, the American Chessie, and the Swedish Storsjöodjuret fall under B11.3.1.1. ("dragon lives in lake").[1]

Theories

[edit]According to the Swedish naturalist and author Bengt Sjögren (1980), present-day lake monsters are variations of older legends of water kelpies.[2] Sjögren claims that the accounts of lake-monsters have changed during history, as do others.[3] Older reports often talk about horse-like appearances, but more modern reports often have more reptile and dinosaur-like appearances; he concludes that the legendary kelpies have evolved into the present day saurian lake-monsters since the discovery of dinosaurs and giant aquatic reptiles and the popularization of them in both scientific and fictional writings and art.[2][4]

The stories cut across cultures, existing in some variation in many countries.[5][6][1] and have undergone what Michel Meurger calls concretizing (The process of turning items, drawings, general beliefs and stories into a plausible whole) and naturalization over time as humanity's view of the world has changed.[3]

In many of these areas, especially around Loch Ness, Lake Champlain and the Okanagan Valley, these lake monsters have become important tourist draws.

In Ben Radford and Joe Nickell's book Lake Monster Mysteries,[7] the authors attribute a vast number of sightings to otter misidentifications. Ed Grabianowski plotted the distribution of North American lake monster sightings and then overlaid this with the distribution of the common otter and found a near perfect match. It turns out that three or four otters swimming in a line look remarkably like a serpentine, humped creature undulating through the water, very easy to mistake for a single creature if you see them from a distance. "This isn't speculation. I'm not making this up," Nickell said. "I've spoken to people who saw what they thought was a lake monster, got closer and discovered it was actually a line of otters. That really happens."[8] Of course, not every supposed lake monster sighting can be attributed to otters, but it is an excellent example of how our perceptions can be fooled.[9]

Paul Barrett and Darren Naish note that the existence of any large animals in isolation (i.e., in a situation where no breeding population exists) is highly unlikely. Naish also observes that the stories are likely remnants of tales meant to keep children safely away from the water.[5][1]

There have been many purported sightings of lake monsters, and even some photographs, but each time these have either been shown to be deliberate deceptions, such as the Lake George Monster Hoax,[10] or serious doubts about the veracity and verifiability have arisen, as with the famous Mansi photograph of Champ.[11]

The most recent lake monster sighting to get widespread attention occurred during post-production of the Champ movie Lucy and the Lake Monster. The filmmakers reviewed their drone footage from production on August 2, 2024, and noticed what appears to be a large creature swimming just below the surface of the water, in Bulwagga Bay. The alleged plesiosaur image is visible in the bottom right portion of the screen, swimming behind a boat containing the two lead actors in the film. The boat was 142 inches from the tip of the bow to the stern and 50.5 inches at the widest point and the alleged plesiosaur appears bigger than the boat. One of the co-writers, Kelly Tabor, believes it to be a foundational piece of evidence for Champ. The second co-writer, Richard Rossi, referred to himself as the "Doubting Thomas," and he shared the entire five minutes of footage with a conclave of scientists with earned doctorates in science for further study of the Tabor-Rossi footage.[12][13]

Examples

[edit]Well-known lake monsters include:

- Mishipeshu, in Lake Superior, Canada and US

- Nessie, in Loch Ness, Scotland

- Morag, in Loch Morar, Scotland

- Lagarfljót Worm, in Lagarfljót, Iceland

- Ogopogo, in Okanagan Lake, Canada

- Lariosauro, in Lake Como, Italy

- Champ, in Lake Champlain, Canada and US

- Memphre, in Lake Memphremagog, Canada and US

- Bessie, in Lake Erie, Canada and US

- Nahuelito, in Nahuel Huapi Lake, Argentina

- Muyso, in Lake Tota, Colombia

- Van Gölü Canavarı, in Lake Van, Turkey

- Inkanyamba, in Howick Falls, South Africa

- Tahoe Tessie, in Lake Tahoe, US

- Flessie, in Flathead Lake, US

- Iliamna Lake monster, in Lake Iliamna, US

- Brosno dragon, in Lake Brosno, Russia

- Mussie, in lake Muskrat, US and Canada

See also

[edit]- River Monsters – Wildlife documentary television series

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sharpe, M. E. (2005). Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 78, 212. ISBN 9780765629531. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ a b Sjögren, Bengt (1980). Berömda vidunder (in Swedish). Settern. ISBN 91-7586-023-6.

- ^ a b Hill, Sharon A. "Cryptozoology and Myth, Part 5: Which came first – the monster or the myth?". sharonahill.com. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Tim Dinsdale (1975) Project Water Horse. The true story of the monster quest at Loch Ness (Routledge & Kegan Paul) ISBN 0-7100-8030-1

- ^ a b Baraniuk, Chris. "The Mythical Monsters That Hide In Lakes". bbc.com. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Meurger, Michel; Gagnon, Claude (1988). Lake Monster Traditions: A Cross-cultural Analysis. Fortean Tomes. ISBN 9781870021005. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Radford, Ben; Nickell, Joe (May 2006). Lake Monster Mysteries: Investigating the World's Most Elusive Creatures. University Press of Kentucky. ASIN B0078XFQKQ.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (June 2007). "Lake Monster Lookalikes". Skeptical Inquirer. 17 (2). Retrieved 23 Feb 2021.

- ^ Grabianowski, Ed. "Paranormal Investigator Joe Nickell Reveals the Truth Behind Modern Cryptozoological Myths". gizmodo.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (December 2004). "The Lake George Monster Hoax". Skeptical Inquirer. 14 (4). Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Bartholomew, Robert E. (June 2013). "New Information Surfaces on 'World's Best Lake Monster Photo,' Raising Questions". Skeptical Inquirer. 37 (3). Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Riddle, Lyn (14 August 2024). "SC filmmaker surprised by lake footage where a sea monster is alleged to live". McClatchy Company. The State. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Bartlett Yaw, Shaundra (12 August 2024). "Champ movie to hold world premiere: Potential footage of plesiosaur surfaced in post-production". Sun Community News. Retrieved 12 August 2024.