Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lingqu

View on Wikipedia

25°35′56″N 110°41′23″E / 25.59889°N 110.68972°E

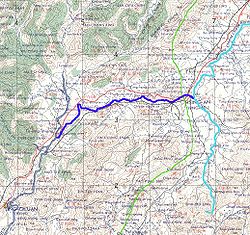

The Lingqu (traditional Chinese: 靈渠; simplified Chinese: 灵渠; pinyin: Líng Qú) is a canal in Xing'an County, near Guilin, in the northwestern corner of Guangxi, China.

Key Information

It connects the Xiang River (which flows north into the Yangtze) with the Li River (which flows south into the Gui River and Xijiang, the latter is one of the major tributaries of Pearl River), and thus is part of a historical waterway between the Yangtze and the Pearl River Delta. It was the first canal in the world to connect two river valleys and enabled boats to travel 2,000 kilometers (1,200 mi) overland between Northern China and the Pearl River Delta.[1] It is also one of the most well-preserved such projects in the world.[2]

The canal is 36.4 kilometers (22.6 mi) long.[3]

History

[edit]In 214 BC, Qin Shi Huang, the First Emperor of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), ordered the construction of a canal connecting the Xiang and the Li rivers, in order to attack the Baiyue tribes in the south. The architect who designed the canal was Shi Lu (Chinese: 史祿). It is the oldest contour canal in the world,[1] receiving its water from the Xiang. It was fitted with thirty-seven flash locks by 825 AD. There is a clear description of pound locks in the twelfth century, which were probably installed one or two centuries before.[4] The canal also aided water conservation by diverting up to a third of the flow of the Xiang to the Li.[3]

The canal has been placed on the UNESCO World Heritage Sites tentative list.[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b The first contour transport canal (PDF), UNESCO Courier, October 1988

- ^ Chen, Anze; Ng, Young; Zhang, Erkuang; Tian, Mingzhong, eds. (2020), "Lingqu Canal", Dictionary of Geotourism, Singapore: Springer, pp. 349–350, doi:10.1007/978-981-13-2538-0_1406, ISBN 978-981-13-2538-0, retrieved September 27, 2023

- ^ a b c "Lingqu Canal". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ Ronan, Colin A. (1995), The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, Cambridge University Press, pp. 213ff, ISBN 9780521467735, retrieved May 23, 2012

Bibliography

[edit]- Day, Lance and McNeil, Ian . (1996). Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06042-7.