Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chinese space program

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

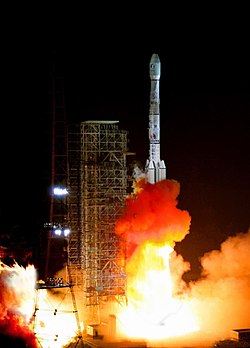

The space program of the People's Republic of China is about the activities in outer space conducted and directed by the government of China. The roots of the Chinese space program trace back to the 1950s, when, with the help of the newly allied Soviet Union, China began development of its first ballistic missile and rocket programs in response to the perceived American (and, later, Soviet) threats. Driven by the successes of Soviet Sputnik 1 and American Explorer 1 satellite launches in 1957 and 1958 respectively, China would launch its first satellite, Dong Fang Hong 1 in April 1970 aboard a Long March 1 rocket, making it the fifth nation to place a satellite in orbit.

China has one of the most active space programs in the world. With space launch capability provided by the Long March rocket family and four spaceports (Jiuquan, Taiyuan, Xichang, Wenchang) within its border, China conducts either the highest or the second highest number of orbital launches each year. It operates a satellite fleet consisting of a large number of communications, navigation, remote sensing and scientific research satellites.[1] The scope of its activities has expanded from low Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars.[2] China is one of the three countries, alongside the United States and Russia, with independent human spaceflight capability.

Currently, most of the space activities carried out by China are managed by the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and the People's Liberation Army Strategic Support Force, which directs the astronaut corps and the Chinese Deep Space Network.[3][4] Major programs include China Manned Space Program, BeiDou Navigation Satellite System, Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, Gaofen Observation and Planetary Exploration of China. In recent years, China has conducted several missions, including Chang'e-4, Chang'e-5, Chang’e-6, Tianwen-1, Tianwen-2, and Tiangong space station.

History

[edit]Early years (1950s to mid-1970s)

[edit]

The Chinese space program began in the form of missile research in the 1950s. After its birth in 1949, the newly founded People's Republic of China was in pursuit of missile technology to build up the nation's defense for the Cold War. In 1955, Qian Xuesen (钱学森), the world-class rocketry scientist, returned to China from the United States. In 1956, Qian submitted a proposal for the development of China's missile program, which was approved in just a few months. On October 8, China's first missile research institute, the Fifth Research Academy under the Ministry of National Defense, was established with less than 200 staff, most of which were recruited by Qian. The event was later recognized as the birth of China's space program.[5]

To fully utilize all available resources, China kick-started its missile development by manufacturing a licensed copy of two Soviet R-2 missiles, which were secretly shipped to China in December 1957 as part of the cooperative technology transfer program between the Soviet Union and China. The Chinese version of the missile was given the code name "1059" with the expectation of being launched in 1959. But the target date was soon postponed due to various difficulties arising from the sudden withdrawal of Soviet technical assistance due to the Sino-Soviet split.[6] Meanwhile, China started constructing its first missile test site in the Gobi desert of Inner Mongolia, which later became the famous Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center (酒泉卫星发射中心), China's first spaceport.[citation needed]

After the launch of mankind's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, Mao Zedong decided during the 8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) on May 17, 1958, to make China an equal of the superpowers (Chinese: "我们也要搞人造卫星"; lit. 'We too need satellites'), by adopting Project 581 with the objective of placing a satellite in orbit by 1959 to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the PRC's founding.[7] This goal was soon proven unrealistic, and it was decided to focus on the development of sounding rockets first.[citation needed]

The first achievement of the program was the launch of T-7M, a sounding rocket that eventually reached the height of 8 km on February 19, 1960. It was the first rocket developed by Chinese engineers.[8] The success was praised by Mao Zedong as a good beginning of an indigenous Chinese rocket development.[9] However, all Soviet technological assistance was abruptly withdrawn after the 1960 Sino-Soviet split, and Chinese scientists continued on the program with extremely limited resources and knowledge.[10] It was under these harsh conditions that China successfully launched the first "missile 1059", fueled by alcohol and liquid oxygen, on December 5, 1960, marking a successful imitation of Soviet missile. The missile 1059 was later renamed as Dongfeng-1 (DF-1, 东风一号).[6]

While the imitation of Soviet missile was still in progress, the Fifth Academy led by Qian had begun the development of Dongfeng-2 (DF-2), the first missile to be designed and built completely by the Chinese. After a failed attempt in March 1962, multiple improvements, and hundreds of engine firing tests, DF-2 achieved its first successful launch on its second attempt on Jun 29, 1964 in Jiuquan. It was considered as a major milestone in China's indigenous missile development history.[11]

In the next few years, Dongfeng-2 conducted seven more launches, all ended in success. On October 27, 1966, as part of the "Two Bombs, One Satellite" project, Dongfeng-2A, an improved version of DF-2, successfully launched and detonated a nuclear warhead at its target.[12] As China's missile industry matures, a new plan of developing carrier rockets and launching satellites was proposed and approved in 1965 with the name Project 581 changed to Project 651.[13] On January 30, 1970, China successfully tested the newly developed two-stage Dongfeng-4 (DF-4) missile, which demonstrated critical technologies like rocket staging, engine in-flight ignition, attitude control.[14] The DF-4 was used to develop the Long March 1 (LM-1 or CZ-1, 长征一号), with a newly designed spin-up orbital insertion solid-propellant rocket motor third stage added to the two existing Nitric acid/UDMH liquid propellant stages.[citation needed]

China's space program benefited from the Third Front campaign to develop basic industry and national defense industry in China's rugged interior in preparation for potential invasion by the Soviet Union or the United States.[15]: 4, 218–219 Almost all of China's new aerospace work units in the late 1960s and early 1970s were established as part of the Third Front and Third Front projects included expansion of Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, building Xichang Satellite Launch Center, and building Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center.[15]: 218–219

On April 24, 1970, China successfully launched the 173 kg Dong Fang Hong I (东方红一号, meaning The East Is Red I) atop a Long March 1 (CZ-1, 长征一号) rocket from Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. It was the heaviest first satellite placed into orbit by a nation. The third stage of the Long March 1 was specially equipped with a 40 m2 solar reflector (观察球) deployed by the centrifugal force developed by the spin-up orbital insertion solid propellant stage.[16] China's second satellite was launched with the last Long March 1 on March 3, 1971. The 221 kg ShiJian-1 (SJ-1, 实践一号) was equipped with a magnetometer and cosmic-ray/x-ray detectors.[citation needed]

In addition to the satellite launch, China also made small progress in human spaceflight. The first successful launch and recovery of a T-7A(S1) sounding rocket carrying a biological experiment (it carried eight white mice) was on July 19, 1964, from Base 603 (六〇三基地).[17] As the space race between the two superpowers reached its climax with the conquest of the Moon, Mao and Zhou Enlai decided on July 14, 1967, that China should not be left behind, and started China's own crewed space program.[18] China's first spacecraft designed for human occupancy was named Shuguang-1 (曙光一号) in January 1968.[19] China's Space Medical Institute (航天医学工程研究所) was founded on April 1, 1968, and the Central Military Commission issued the order to start the selection of astronauts. The first crewed space program, known as Project 714, was officially adopted in April 1971 with the goal of sending two astronauts into space by 1973 aboard the Shuguang spacecraft. The first screening process for astronauts had already ended on March 15, 1971, with 19 astronauts chosen. But the program was soon canceled in the same year due to political turmoil, ending China's first human spaceflight attempt.[citation needed]

While CZ-1 was being developed, the development of China's first long-range intercontinental ballistic missile, namely Dongfeng-5 (DF-5), has started since 1965. The first test flight of DF-5 was conducted in 1971. After that, its technology was adopted by two different models of Chinese medium-lift launch vehicles being developed. One of the two was Feng Bao 1 (FB-1, 风暴一号) developed by Shanghai's 2nd Bureau of Mechanic-Electrical Industry, the predecessor of Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST). The other parallel medium-lift LV program, also based on the same DF-5 ICBM and known as Long March 2 (CZ-2, 长征二号), was started in Beijing by the First Research Academy of the Seventh Ministry of Machine Building, which later became China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT). Both FB-1 and CZ-2 were fueled by N2O4 and UDMH, the same propellant used by DF-5.[20]

On July 26, 1975, FB-1 made its first successful flight, placing the 1107-kilogram Changkong-1 (长空一号) satellite into orbit. It was the first time that China launched a payload heavier than 1 metric ton.[20] Four months later, on November 26, CZ-2 successfully launched the FSW-0 No.1 (返回式卫星零号) recoverable satellite into orbit. The satellite returned to earth and was successfully recovered three days later, making China the third country capable of recovering a satellite, after the Soviet Union and the United States.[21] FB-1 and CZ-2, which were developed by two different institutes, were later evolved into two different branches of the classic Long March rocket family: Long March 4 and Long March 2.[citation needed]

As part of the Third Front effort to relocate critical defense infrastructure to the relatively remote interior (away from the Soviet border), it was decided to construct a new space center in the mountainous region of Xichang in the Sichuan province, code-named Base 27. After expansion, the Northern Missile Test Site was upgraded as a test base in January 1976 to become the Northern Missile Test Base (华北导弹试验基地) known as Base 25.[citation needed]

New era (late 1970s to 1980s)

[edit]After Mao died on September 9, 1976, his rival, Deng Xiaoping, denounced during the Cultural Revolution as reactionary and therefore forced to retire from all his offices, slowly re-emerged as China's new leader in 1978. At first, the new development was slowed. Then, several key projects deemed unnecessary were simply cancelled—the Fanji ABM system, the Xianfeng Anti-Missile Super Gun, the ICBM Early Warning Network 7010 Tracking Radar and the land-based high-power anti-missile laser program. Nevertheless, some development did proceed. The first Yuanwang-class space tracking ship was commissioned in 1979. The first full-range test of the DF-5 ICBM was conducted on May 18, 1980. The payload reached its target located 9300 km away in the South Pacific (7°0′S 117°33′E / 7.000°S 117.550°E) [dubious – discuss] and retrieved five minutes later by helicopter.[22] In 1982, Long March 2C (CZ-2C, 长征二号丙), an upgraded version of Long March 2 based on DF-5 with 2500 kg low Earth orbit (LEO) payload capacity, completed its maiden flight. Long March 2C, along with many of its derived models, eventually became the backbone of Chinese space program in the following decades.[citation needed]

As China changing its direction from political activities to economy development since late 1970s, the demand for communications satellites surged. As a result, the Chinese communications satellite program, code name Project 331, was started on March 31, 1975. The first generation of China's own communication satellites was named Dong Fang Hong 2 (DFH-2, 东方红二号), whose development was led by the famous satellite expert Sun Jiadong.[23] Since communications satellites works in the geostationary orbit much higher than what the existing carrier rockets could reach, the launching of communications satellites became the next big challenge for the Chinese space program.[citation needed]

The task was assigned to Long March 3 (CZ-3, 长征三号), the most advanced Chinese launch vehicle in the 1980s. Long March 3 was a derivative of Long March 2C with an additional third stage, designed to send payloads to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). When the development of Long March 3 began in the early 1970s, the engineers had to make a choice between the two options for the third stage engine: either the traditional engine fueled by the same hypergolic fuels used by the first two stages, or the advanced cryogenic engine fueled by liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. Although the cryogenic engine plan was much more challenging than the other one, it was eventually chosen by Chief Designer Ren Xinmin (任新民), who had foreseen the great potential of its use for the Chinese space program in the coming future. The development of cryogenic engine with in-flight re-ignition capability began in 1976 and wasn't completed until 1983.[24] At the same time, Xichang Satellite Launch Center (西昌卫星发射中心) was chosen as the launch site of Long March 3 due to its low latitude, which provides better GTO launch capability.[citation needed]

On January 29, 1984, Long March 3 performed its maiden flight from Xichang, carrying the first experimental DFH-2 satellite. Unfortunately, because of the cryogenic third-stage engine failed to re-ignite during flight, the satellite was placed into a 400 km LEO instead of its intended GTO. Despite the rocket failure, the engineers managed to send the satellite into an elliptic orbit with an apoapsis of 6480 km using the satellite's own propulsion system. A series of tests were then conducted to verify the performance of the satellite.[23] Thanks to the hard work by the engineers, the cause of the cryogenic engine failure was located quickly, followed by improvements applied on the second rocket awaiting launch.[24]

On April 8, 1984, less than 70 days after the first failure, Long March 3 launched again from Xichang. It successfully inserted the second experimental DFH-2 satellite into target GTO on its second attempt. The satellite reached the final orbit location on April 16 and was handed over to the user on May 14, becoming China's first geostationary communications satellite.[25] The success made China the fifth country in the world with independent geostationary satellite development and launch capability.[24] Less than two years later, on February 1, 1986, the first practical DFH-2 communications satellite was launched into orbit atop a Long March 3 rocket, ending China's reliance on foreign communications satellite.[25]

During the 1980s, human spaceflights in the world became significantly more active than before as the American Space Shuttle and Soviet space stations were put in service respectively. It was in the same period that the previously canceled Chinese human spaceflight program was quietly revived again. In March 1986, Project 863 (863计划) was proposed by four scientists Wang Daheng, Wang Ganchang, Yang Jiachi, and Chen Fangyun. The goal of the project was to stimulate the development of advanced technologies, including human spaceflight. Followed by the approval of Project 863, the early study of Chinese human spaceflight program in the new era had begun.[26]

The rise and fall of commercial launches (1990s)

[edit]

After the initial success of Long March 3, further development of the Long March rocket series allowed China to announce a commercial launch program for international customers in 1985, which opened up a decade of commercial launches by Chinese launch vehicles in the 1990s.[27] The launch service was provided by China Great Wall Industry Corporation (CGWIC) with support from CALT, SAST and China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General (CLTC). The first contract was signed with AsiaSat in January 1989 to launch AsiaSat 1, a communications satellite manufactured by Hughes. It was previously a satellite owned by Westar but placed into a wrong orbit due to kick motor malfunction before being recovered in the STS-51-A mission in 1984.[citation needed]

On April 7, 1990, a Long March 3 rocket successfully launched AsiaSat 1 into target geosynchronous transfer orbit with high precision, fulfilling the contract. As its very first commercial launch ended in full success, the Chinese commercial launch program was introduced to the world with a good opening.[28]

Although Long March 3 completed its first commercial mission as expected, its 1,500 kg payload capability was not capable of placing the new generation of communication satellites, which were usually over 2,500 kg, into geostationary transfer orbit. To deal with the problem, China introduced Long March 2E (CZ-2E, 长征二号E), the first Chinese rocket with strap-on boosters that can place up to 3,000 kg payload into GTO. The development of Long March 2E began in November 1988 when CGWIC was awarded the contract of launching two Optus satellites by Hughes mostly due to its low price. At that time, neither the rocket nor the launch facility was anything more than concepts on paper. Yet the engineers of CALT eventually built all the hardware from scratch in a record-breaking period of 18 months, which impressed the American experts.[29] On September 16, 1990, Long March 2E, carrying an Optus mass simulator, conducted its test flight and reached intended orbit as designed. The success of the test flight was a huge inspiration for all parties involved and brought optimism about the coming launch of actual Optus satellites.[30]

However, an accident occurred during this highly anticipated launch on March 22, 1992, at Xichang Satellite Launch Center. After initial ignition, all engines shut down unexpectedly. The rocket was unable to lift off, resulting in a launch abort while being live-streamed to the world.[31] The post-launch investigation revealed that some minor aluminum scraps caused a shortage in the control circuit, triggering an emergency shutdown of all engines. Although the huge vibration brought by the short-lived ignition had led to a rotation of the whole rocket by 1.5 degree clockwise and partial displacement of the supporting blocks, the rocket filled with propellant was still standing on the launch pad when the dust settled. After a rescue mission that lasted for 39 hours, the payload, rocket, and launch facilities were all preserved intact, avoiding huge losses. Less than five months later, on August 14, a new Long March 2E rocket successfully lifted off from Xichang, sending the Optus satellite into orbit.[32]

In June 1993, the China Aerospace Corporation was founded in Beijing. It was also granted the title of China National Space Administration (CNSA).[33] A improved version of Long March 3, namely Long March 3A (CZ-3A, 长征三号甲) with 2,600 kg payload capacity to GTO, was put into service in 1994. However, on February 15, 1996, during the first flight of the further improved Long March 3B (CZ-3B, 长征三号乙) rocket carrying Intelsat 708, the rocket veered off course immediately after clearing the launch platform, crashing 22 seconds later. The crash killed 6 people and injured 57, making it the most disastrous event in the history of Chinese space program.[34][35] Although the Long March 3 rocket successfully launched APStar 1A communication satellites on July 3, it came across a third stage re-ignition malfunction during the launch of ChinaSat 7 on August 18, resulting in another launch failure.[36][37]

The two launch failures within a few months dealt a severe blow to the reputation of the Long March rockets. As a consequence, the Chinese commercial launch service was facing canceled orders, refusal of insurance, or greatly increased insurance premium.[37] Under such a harsh circumstance, the Chinese space industry initiated full-scale quality improving activities. A closed-loop quality management system was established to fix quality issues in both the technical and administrative aspects.[35][38] The strict quality management system remarkably increased the success rate ever since. Within the next 15 years, from October 20, 1996, up until August 16, 2011, China had achieved 102 consecutive successful space launches.[39] On August 20, 1997, Long March 3B accomplished its first successful flight on its second attempt, placing the 3,770 kg Agila-2 communications satellite into orbit. It offered a GTO payload capacity as high as 5,000 kg capable of putting different kinds of heavy satellites available on the international market into orbit.[40] Ever since then, Long March 3B had become the backbone of China's mid to high Earth orbit launches and been granted the title of most powerful rocket by China for nearly 20 years. In 1998, the administrative branch of China Aerospace Corporation was split and then merged into the newly founded Commission for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense while retaining the title of CNSA. The remaining part was split again into China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) and China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) in 1999.[33]

While the Long March rockets were trying to take back the commercial launch market it lost, the political suppression from the United States approached. In 1998, the United States accused Hughes and Loral of exporting technologies that inadvertently helped China's ballistic missile program while resolving issues that caused the Long March rocket launch failures. The accusation ultimately led to the release of Cox Report, which further accused China of stealing sensitive technologies. In the next year, the U.S. Congress passed the act that put commercial satellites into the list restricted by International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and prohibited launches of satellites containing U.S. made components onboard Chinese rockets.[41][42] The regulation abruptly killed the commercial cooperation between China and the United States. The two Iridum satellites launched by Long March 2C on June 12, 1999, became the last batch of American satellites launched by Chinese rocket.[43] Furthermore, due to the strict regulation applied and the U.S. dominance in space industry, the Long March rockets had been de facto excluded from the international commercial launch market, causing a stagnation of the Chinese commercial launch program in the next few years.[41]

Despite the turmoil of commercial launches, the Chinese space program still made a huge breakthrough near the end of the decade. At 6:30 (China Standard Time) on November 20, 1999, Shenzhou-1 (神舟一号), the first uncrewed Shenzhou spacecraft (神舟载人飞船) designed for human spaceflight, was successfully launched atop a Long March 2F (CZ-2F, 长征二号F) rocket from Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The spacecraft was inserted into low earth orbit 10 minutes after lift off. After orbiting the Earth for 14 rounds, the spacecraft initiated the return procedure as planned and landed safely in Inner Mongolia at 03:41 on November 21, marking the full success of China's first Shenzhou test flight. Following the announcement of the success of the mission, the previously secretive Chinese human spaceflight program, namely the China Manned Space Program (CMS, 中国载人航天工程), was formally made public. CMS, which was formally approved on September 21, 1992, by the CCP Politburo Standing Committee as Project 921, has been the most ambitious space program of China since its birth.[44] Its goals can be described as "Three Steps": Crewed spacecraft launch and return; Space laboratory for short-term missions; Long-term modular space station.[45] Due to its complex nature, a series of advanced projects were introduced by the program, including Shenzhou spacecraft, Long March 2F rocket, human spaceflight launch site in Jiuquan, Beijing Aerospace Flight Control Center, and Astronaut Center of China in Beijing. In terms of astronauts, fourteen candidates were selected to form the People's Liberation Army Astronaut Corps and started accepting spaceflight training.[citation needed]

Breakthroughs by Shenzhou and Chang'e (2000s)

[edit]Since the beginning of 21st century, China has been experiencing rapid economic growth, which led to higher investment into space programs and multiple major achievements in the following decades. In November 2000, the Chinese government released its first white paper entitled China's Space Activities, which described its goals in the next decade as:[46]

- To build up an earth observation system for long-term stable operation.

- To set up an independently operated satellite broadcasting and telecommunications system.

- To establish an independent satellite navigation and positioning system.

- To upgrade the overall level and capacity of China's launch vehicles.

- To realize manned spaceflight and establish an initially complete R&D and testing system for manned space projects.

- To establish a coordinated and complete national satellite remote-sensing application system.

- To develop space science and explore outer space.

The independent satellite navigation and positioning system mentioned by the white paper was Beidou (北斗卫星导航系统). The development of Beidou dates back to 1983 when academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Chen Fangyun designed a primitive satellite navigation systems consisting of two satellites in the geostationary orbit. Sun Jiadong, the famous satellite expert of China, later proposed a "three-step" strategy to develop China's own satellite navigation system, whose service coverage expands from China to Asia then the globe. The two satellites of the "first step", namely BeiDou-1, were launched in October and December 2000.[47] As an experimental system, Beidou-1 offered basic positioning, navigation and timing services to limited areas in and around China.[48] After a few years of experiment, China started the construction of BeiDou-2, a more advanced system to serve the Asia-Pacific region by launching the first two satellites in 2007 and 2009 respectively.[49]

Another major goal specified by the white paper was to realize crewed spaceflight. The China Manned Space Program continued its steady evolvement in the 21st century after its initial success. From January 2001 to January 2003, China conducted three uncrewed Shenzhou spacecraft test flights, validating all systems required by human spaceflight. Among these missions, the Shenzhou-4 launched on December 30, 2002, was the last uncrewed rehearsal of Shenzhou. It flew for 6 days and 18 hours and orbited around the Earth for 108 circles before returning on January 5, 2003.[50]

On October 15, 2003, the first Chinese astronaut Yang Liwei (杨利伟) was launched aboard Shenzhou-5 (神舟五号) spacecraft atop a Long March 2F rocket from Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The spacecraft was inserted into orbit ten minutes after launch, making Yang the first Chinese in space. After a flight of more than 21 hours and 14 orbits around the Earth, the spacecraft returned and landed safely in Inner Mongolia in the next morning, followed by Yang's walking out of the return capsule by himself.[51] The complete success of Shenzhou 5 mission was widely celebrated in China and received worldwide endorsements from different people and parties, including UN Secretary General Kofi Annan.[52] The mission, officially recognized by China as the second milestone of its space program after the launch of Dongfanghong-1, marked China's standing as the third country capable of completing independent human spaceflight, ending the over 40-year long duopoly by the Soviet Union/Russia and the United States.[53]

The China Manned Space Program did not stop its footsteps after its historic first crewed spaceflight. In 2005, two Chinese astronauts, Fei Junlong (费俊龙) and Nie Haisheng (聂海胜), safely completed China's first "multi-person and multi-day" spaceflight mission aboard Shenzhou-6 (神舟六号) between October 12 and 17.[54] On 25 September 2008, Shenzhou-7 (神舟七号) was launched into space with three astronauts, Zhai Zhigang (翟志刚), Liu Boming (刘伯明) and Jing Haipeng (景海鹏). During the flight, Zhai and Liu conducted China's first spacewalk in orbit.[55]

Around the same time, China began preparation for extraterrestrial exploration, starting with the Moon. The early research of Moon exploration of China dates back to 1994 when its necessity and feasibility were studied and discussed among Chinese scientists.[56] As a result, the white paper of 2000 enlisted the Moon as the primary target of China's deep space exploration within the decade. In January 2004, the year after China's first human spaceflight mission, the Chinese Moon orbiting program was formally approved and was later transformed into Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP, 中国探月工程). Just like several other space programs of China, CLEP was divided into three phases, which were simplified as "Orbiting, Landing, Returning" (“绕、落、回”), all to be executed by robotic probes at the time of planning.[57]

On October 24, 2007, the first lunar orbiter Chang'e-1 (嫦娥一号) was successfully launched by a Long March 3A rocket, and was inserted into Moon orbit on November 7, becoming China's first artificial satellite of the Moon. It then performed a series of surveys and produced China's first lunar map. On March 1, 2009, Chang'e-1, which had been operating longer than its designed life span, performed a controlled hard landing on lunar surface, concluding the Chang'e-1 mission.[58] Being China's first deep space exploration mission, Chang'e-1 was recognized by China as the third milestone of the Chinese space program and the admission ticket to the world club of deep space explorations.[53]

In others areas, despite the harsh sanction imposed by the United States since 1999, China still made some progress in terms of commercial launches within the first decade of the 21st century. In April 2005, China successfully conducted its first commercial launch since 1999 by launching the APStar 6 communications satellite manufactured by French company Alcatel atop a Long March 3B rocket.[59] In May 2007, China launched NigComSat-1 satellite developed by China Academy of Space Technology. This was the first time China provided the full service from satellite manufacture to launch for international customers.[60][61]

Expansion and revolution (2010s)

[edit]

From 2000 to 2010, China had quadrupled its GDP and became the second largest economy in the world.[62] Due to the rapid development of economy activities across the nation, the demand for high-resolution Earth observation systems increased in a remarkable manner. To end the reliance on foreign high-resolution remote sensing data, China initiated the China High-resolution Earth Observation System program (高分辨率对地观测系统), most commonly known as Gaofen (高分), in May 2010. Its purpose is to establish an all-day, all-weather coverage Earth observation system for satisfying the requirements of social development as part of the Chinese space infrastructures.[63] The first Gaofen satellite, Gaofen 1, was launched into orbit on April 26, 2013, followed by more satellites being launched into different orbits in the next few years to cover different spectra. As of today, more than 30 Gaofen satellites are being operated by China as the completion of the space-based section of Gaofen was announced in late 2022.[64]

The Beidou Navigation Satellite System proceeded in extraordinary speed after the launch of first Beidou-2 satellite in 2007. As many as five Beidou-2 navigation satellites were launched in 2010 alone. In late 2012, the Beidou-2 navigation system consisting of 14 satellites was completed and started providing service to Asia-Pacific region.[49] The construction of more advanced Beidou-3 started since November 2017. Its buildup speed was even more astonishing than before as China launched 24 satellites into medium Earth orbit, 3 into inclined geosynchronous orbit, and 3 into geostationary orbit within just three years.[65] The final satellite of Beidou-3 was successfully launched by a Long March 3B rocket on June 23, 2020.[66] On July 31, 2020, CCP general secretary Xi Jinping made the announcement on the Beidou-3 completion ceremony,[67] declaring the commission of Beidou-3 system across the globe.[68][69] The completed Beidou-3 navigation system integrates navigation and communication function, and possesses multiple service capabilities, including positioning, navigation and timing, short message communication, international search and rescue, satellite-based augmentation, ground augmentation and precise point positioning.[48] It is now one of the four core system providers designated by the International Committee on Global Navigation Satellite Systems of the United Nations.[70]

The China Manned Space Program continued to make breakthroughs in human spaceflight technologies in 2010s. In the early 2000s, the Chinese crewed space program continued to engage with Russia in technological exchanges regarding the development of a docking mechanism used for space stations.[71] Deputy Chief Designer, Huang Weifen, stated that near the end of 2009, the China Manned Space Agency began to train astronauts on how to dock spacecraft.[72] In order to practice space rendezvous and docking, China launched an 8,000 kg (18,000 lb) target vehicle, Tiangong-1 (天宫一号), in 2011,[73] followed by the uncrewed Shenzhou 8 (神舟八号). The two spacecraft performed China's first automatic rendezvous and docking on 3 November 2011, which verified the performance of docking procedures and mechanisms.[74] About 9 months later, in June 2012, Tiangong 1 completed the first manual rendezvous and docking with Shenzhou 9 (神舟九号), a crewed spacecraft carrying Jing Haipeng, Liu Wang (刘旺) and China's first female astronaut Liu Yang (刘洋).[75] The successes of Shenzhou 8 and 9 missions, especially the automatic and manual docking experiments, marked China's advancement in space rendezvous and docking. Tiangong 1 was later docked with crewed spacecraft Shenzhou 10 (神舟十号) carrying astronauts Nie Haisheng, Zhang Xiaoguang (张晓光) and Wang Yaping (王亚平), who conducted multiple scientific experiments, gave lectures to over 60 million students in China, and performed more docking tests before returning to the Earth safely after 15 days in space.[76] The completion of missions from Shenzhou 7 to 10 demonstrated China's mastery of all basic human spaceflight technologies, ending phase 1 of "Second Step".[77]

Although Tiangong 1 was considered as a space station prototype, its functionality was still remarkably weaker than decent space laboratories. Tiangong-2 (天宫二号), the first real space laboratory of China, was launched into orbit on September 15, 2016. It was visited by Shenzhou 11 crew a month later. Two astronauts, Jing Haipeng and Chen Dong (陈冬) entered Tiangong 2 and were stationed for about 30 days, breaking China's record for the longest human spaceflight mission while carrying out different types of human-attended experiments. In April 2017, China's first cargo spacecraft, Tianzhou-1 (天舟一号), docked with Tiangong 2 and completed multiple in-orbit propellant refueling tests.[78]

In terms of deep space explorations, after completing the objective of "Orbiting" in 2007, the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program started preparing for the "Landing" phase. China's second lunar probe, Chang'e-2 (嫦娥二号), was launched on October 1, 2010. It used trans-lunar injection orbit to reach the Moon for the first time and imaged the Sinus Iridum region where future landing missions were expected to occur.[79] On December 2, 2013, a Long March 3B rocket launched Chang'e-3 (嫦娥三号), China's first lunar lander, to the Moon. On December 14, Chang'e 3 successfully landed on the Sinus Iridum region, making China the third country that made soft-landing on an extraterrestrial body. A day later, the Yutu rover (玉兔号月球车) was deployed to the lunar surface and started its survey, achieving the goal of "landing and roving" for the second phase of CLEP.[80]

In addition to lunar exploration, it is worth noting that China made its first attempt of interplanetary exploration during the same period. Yinghuo-1 (萤火一号), China's first Mars orbiter, was launched on board the Russian Fobos-Grunt spacecraft as an additional payload in November 2011. Yinghuo-1 was a mission in cooperation with Russian Space Agency. It was a relatively small project initiated by National Space Science Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences instead of a major space program managed by the state space agency. The Yinghuo-1 orbiter weighed about 100 kg and was carried by the Fobos-Grunt probe. It was expected to detach from the Fobos-Grunt probe and injected into Mars orbit after reaching Mars.[81] However, due to an error of the onboard computer, the Fobos-Grunt probe failed to start its main engine and was stranded in the low Earth orbit after launch. Two months later, Fobos-Grunt, along with the Yinghuo-1 orbiter, re-entered and eventually burned up in the Earth atmosphere, resulting in a mission failure.[82] Although the Yinghuo-1 mission did not achieve its original goal due to factors not controlled by China, it led to the dawn of the Chinese interplanetary explorations by gathering a group of talents dedicated to interplanetary research for the first time.[81] On December 13, 2012, the Chinese lunar probe Chang'e 2, which was in an extended mission after the conclusion of its primary tasks in lunar orbit, made a flyby of asteroid Toutatis with closest approach being 3.2 kilometers, making it China's first interplanetary probe.[83][84] In 2016, the first Chinese independent Mars mission was formally approved and listed as one of the major tasks in "White Paper on China's Space Activities in 2016". The mission, which was planned in an unprecedented manner, aimed to achieve Mars orbiting, landing and roving in one single attempt in 2020.[85]

While China was making remarkable progress in all areas above, the Long March rockets, the absolute foundation of Chinese space program, were also experiencing a crucial revolution. Ever since 1970s, the Long March rocket family had been using dinitrogen tetroxide and UDMH as propellant for liquid engines. Although this hypergolic propellant is simple, cheap and reliable, its disadvantages, including toxicity, environmental damages, and low specific impulse, hindered Chinese carrier rockets from being competitive against other space powers since the mid-1980s. To get rid of such unsatisfying situation, China commenced the study of new propellant selection since the introduction of Project 863 in 1986. After an early study that lasted for over a decade, the development of a 120-ton rocket engine burning LOX and kerosene in staged combustion cycle were formally approved in 2000.[86] Despite setbacks like engine explosions during initial firing tests, the development team still made breakthroughs in key technologies like superalloy production and engine ignition and completed its first long duration firing test in 2006.[87] The engine, which was named YF-100, was eventually certified in 2012, and the first engine for actual flight was ready in 2014.[88][89] On September 20, 2015, the Long March 6 (长征六号), a small rocket using one YF-100 engine on its first stage, successfully conducted its maiden flight.[90] On June 25, 2016, the medium-lift Long March 7 (长征七号), which was equipped with six YF-100 engines, completed its maiden flight in full success, increasing the maximum LEO payload capacity by Chinese rockets to 13.5 tons. The successes of Long March 6 and 7 signified the introduction of the "new generation of Long March rockets" powered by clean and more efficient engines.[91]

The maiden launch of Long March 7 was also the very first launch from Wenchang Space Launch Site (文昌航天发射场) located in Wenchang, Hainan Province. It marked the inauguration of Wenchang on the world stage of space activities. Compared with the old Jiuquan, Taiyuan, and Xichang, the Wenchang Space Launch Site, whose construction began in September 2009, is China's latest and most advanced spaceport. Rockets launched from Wenchang can send ten to fifteen percent more payloads in mass to orbit thanks to its low latitude.[92] Additionally, due to its geographic location, the drop zones of rocket debris produced by rocket launches are in the ocean, eliminating threats posed to people and facilities on the ground. Wenchang's coastal location also allows larger rockets to be delivered to launch site by sea, which is difficult, if not impossible, for inland launch sites due to the size limits of tunnels needed to be passed through during transportations.[93]

The biggest breakthrough within the decade, if not decades, were brought by Long March 5 (长征五号), the leading role of the new generation of Long March rockets and China's first heavy-lift launch vehicle. The early study of Long March 5 can be traced back to 1986, and the project was formally approved in mid-2000s. It applied 247 new technologies during its development while over 90% of its components were newly developed and applied for the first time.[94] Instead of using the classic 3.35-meter-diameter core stage and 2.25-meter-diameter side boosters, the 57-meter tall Long March 5 consists of one 5-meter-diameter core stage burning LH2/LOX and four 3.35-meter-diameter side boosters burning kerosene/LOX. With a launch mass as high as 869 metric tons and 10,573 kN lift-off thrust, the Long March 5, being China's most powerful rocket, is capable of lifting up to 25 tons of payload to LEO and 14 tons to GTO, making it more than 2.5 times as much as the previous record holder (Long March 3B) and nearly as equal as the most powerful rocket in the world at that time (Delta IV Heavy).[95][96] Due to its unprecedented capability, the Long March 5 was expected as the keystone for the Chinese space program in the early 21st century. However, after a successful maiden flight in late 2016, the second launch of the Long March 5 on July 2, 2017, suffered a failure, which was considered as the biggest setback for Chinese space program in nearly two decades.[97] Because of the failure, the Long March 5 was grounded indefinitely until the problem was located and resolved, and multiple planned major space missions were either postponed or facing the risk of being postponed in the next few years.[citation needed]

Despite the uncertain future of Long March 5, China managed to make history in space explorations with existing hardware in the next two years. Due to tidal locking, the Moon has been orbiting the Earth as the only natural satellite by facing it with the same side. Humans had never seen the far side of the Moon until the Space Age. Although humans have already got quite an amount of knowledge about the overall condition of the far side of the Moon in early 21st century with the help of numerous visits by lunar orbiters since the 1960s, no country had ever explored the area in close distance due to lack of communications on the far side. This missing piece was eventually filled by China's Chang'e-4 (嫦娥四号) mission in 2019. To solve the communications problem, China launched Queqiao (鹊桥号), a relay satellite orbiting around the Earth–Moon L2 Lagrangian point, in May 2018 to enable communications between the far side of the Moon and the Earth.[98] On December 8, 2018, the Chang'e 4, which was originally built as the backup of Chang'e 3, was launched by a Long March 3B rocket from Xichang and entered lunar orbit on December 12.[99][100] On January 3, 2019, Chang'e 4 successfully soft-landed at the Von Kármán (lunar crater) on the far side of the Moon, and returned the first close-up image of the lunar surface on the far side.[101] A rover named Yutu-2 (玉兔二号) was deployed onto the lunar surface a few hours later, leaving the first trial on the far side.[102] The accomplishment of a series of tasks by Chang'e-4 made China the first country to successfully achieved soft-landing and roving on the far side of the Moon. Because of its great success, the project team received IAF World Space Award of 2020.[103]

Aside from Chang'e 4, there were some other events worth noting during this period. In August 2016, China launched world's first quantum communications satellite Mozi (墨子号).[104] In June 2017, the first Chinese X-ray astronomy satellite named Huiyan (慧眼) was launched into space.[105] In August of the same year, the Astronaut Center of China organized a joint training in which sixteen Chinese and two ESA astronauts participated. It was the first time that foreign astronauts took part in astronaut training organized by China.[106][107] In 2018, China performed more orbital launches than any other countries on the planet for the first time in history.[108] On June 5, 2019, China conducted its first Sea Launch with Long March 11 (长征十一号) in the Yellow Sea.[109] On July 25, Chinese company i-Space became the first Chinese private company to successfully conduct an orbital launch with its Hyperbola-1 small solid rocket.[110]

As the 2010s came to an end, the Chinese space program was poised to conclude the decade with an inspiring event. On December 27, 2019, after a grounding and fixture that lasted for 908 days, the Long March 5 rocket conducted a highly anticipated return-to-flight mission from Wenchang. The mission ended in full success by placing Shijian-20, the heaviest satellite China had ever built, into the intended supersynchronous orbit.[111] The flawless return of Long March 5 swept away all the depressions brought by its last failure since 2017. With its great power, the Long March 5 cleared the paths to multiple world-class space projects, allowing China to make great strides toward its ambitions in the coming 2020s.[112][113][114]

2020-present

[edit]

Being the product of latest technology and engineering by Chinese space industry in the early 21st century, the flight-proven Long March 5 unleashed the potential of Chinese space program to a great extent. Various projects previously restricted by the mass and size limits of the payloads were now offered a chance of realization. Ever since 2020, with the help of Long March 5, the Chinese space program has made tremendous progress in multiple areas by completing some of the most challenging missions ever conducted in history of space explorations, impressing the world like never before.[citation needed]

The "Third Step" of China Manned Space Program kicked off in 2020. Long March 5B, a variant of Long March 5, conducted its maiden flight successfully on May 5, 2020. Its high payload capacity and large payload fairing space enabled the delivery of Chinese space station modules to low Earth orbit.[115] On April 29, 2021, Tianhe core module (天和核心舱), the 22-tonne core module of the space station, was successfully launched into Low Earth orbit by a Long March 5B rocket,[116] marking the beginning of the construction of the China Space Station, also known as Tiangong (天宫空间站), followed by unprecedented high frequency of human spaceflight missions. A month later, China launched Tianzhou-2, the first cargo mission to the space station.[117] On June 17, Shenzhou-12, the first crewed mission to the Chinese Space Station consisting of Nie Haisheng, Liu Boming and Tang Hongbo, was launched from Jiuquan.[118] The crew docked with Tianhe and entered the core module about 9 hours after launch, becoming the first residents of the station. The crew lived and worked on the space station for three months, conducted two spacewalks, and returned to Earth safely on September 17, 2021.[119] breaking the record of longest Chinese human spaceflight mission (33 days) previously made by Shenzhou-11.[120] Roughly a month later, the Shenzhou-13 crewed was launched to the station. Astronauts Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping and Ye Guangfu completed the first long-duration spaceflight mission of China that lasted for over 180 days before returning to Earth safely on April 16, 2022.[121] Astronaut Wang Yaping became the first Chinese female to perform a spacewalk during the mission.[122]

Starting from May 2022, the China Manned Space Program had entered the space station assembly and construction phase. On June 5, 2022, Shenzhou-13 was launched and docked to Tianhe core module. The crew, including Chen Dong, Liu Yang and Cai Xuzhe, were expected to welcome the arrival of two space station modules during the six-month mission.[123] On July 24, the third Long March 5B rocket lifted off from Wenchang, carrying the 23.2 t Wentian laboratory module (问天实验舱), the largest and heaviest spacecraft ever built and launched by China, into orbit. The module docked with the space station less than 20 hours later, adding the second module and the first laboratory module to it.[124] On September 30, the new Wentian module was rotated from the forward docking port to starboard parking port.[125] On October 31, the Mengtian laboratory module (梦天实验舱), the third and final module of China Space Station, was launched by another Long March 5B rocket into orbit and docked with the space station in less than 13 hours later.[126] On November 3, the 'T-shape' China Space Station was completed after the successful transposition of the Mengtian module.[127] On November 29, Shenzhou-15 was launched and later docked with China Space Station. Astronauts Fei Junlong, Deng Qingming, and Zhang Lu were welcomed by the Shenzhou-14 crew on board the station, completing the first crew gathering and handover in space by Chinese astronauts and starting the era of continuous Chinese astronaut presence in space.[128][129]

The third phase of Chinese Lunar Exploration Program was also allowed to proceed in 2020. As preparation, China conducted Chang'e 5-T1 mission in 2014. By completing its main task on November 1, 2014, China demonstrated the capability of returning a spacecraft from the lunar orbit back to Earth safely, paving the way for the lunar sample return mission to be conducted in 2017.[130] However, the failure of the second Long March 5 mission disrupted the original plan. Despite the readiness of the spacecraft, the mission had to be postponed due to the unavailability of its launch vehicle, until the successful return-to-flight of Long March 5 in late 2019.[131] On November 24, 2020, the sample return mission, entitled Chang'e-5 (嫦娥五号), kicked off as the Long March 5 rocket launched the 8.2 t spacecraft stack into space.[132] The spacecraft entered lunar orbit on November 28, followed by a separation of the stack into two parts. The lander landed near Mons Rümker in Oceanus Procellarum on December 1 and started the sample collection process the next day.[133] Two days after the landing, on December 3, the ascent vehicle attached to the lander took off from lunar surface and entered lunar orbit, carrying the container with collected samples. This was the first time that China launched a spacecraft from an extraterrestrial body.[134][135] On December 6, the ascent vehicle successfully docked with the orbiter in lunar orbit and transferred the sample container to the return capsule, accomplishing the first robotic rendezvous and docking in lunar orbit in history.[136] On December 13, the orbiter, along with the return module, entered the orbit back to Earth after main engine burns.[137] The return capsule eventually landed intact in Inner Mongolia on December 17, sealing the perfect completion of the mission.[138]

On December 19, 2020, CNSA hosted the Chang'e-5 lunar sample handover ceremony in Beijing. By weighing the sample container taken out from the return capsule, CNSA announced that Chang'e-5 retrieved 1,731 grams of samples from the Moon.[139] Being the most complex mission completed by China at the time, the Chang'e-5 mission achieved multiple remarkable milestones, including China's first lunar sampling, first liftoff from an extraterrestrial body, first automated rendezvous and docking in lunar orbit (by any nation) and the first spacecraft carrying samples to re-enter Earth's atmosphere at high speed.[140] Its success also marked the completion of the goal of "Orbiting, Landing, Returning" planned by CLEP since 2004.[141]

Prior to the launch of Chang'e-5, which targeted the Moon 380,000 km away from the Earth, China's first Mars probe had departed, heading to the Mars 400 million kilometers away. Ever since the approval of the Mars mission in 2016, China had developed various technologies required, including deep space network, atmospheric entry, lander hovering and obstacle avoidance.[142][143] Long March 5, the only launch vehicle capable of delivering the spacecraft, was back to service after its critical return-to-flight in December 2019. As a result, all things were ready when the launch windows of July 2020 arrived. On April 24, 2020, CNSA officially announced the program of Planetary Exploration of China and named China's first independent Mars mission as Tianwen-1 (天问一号).[144] On July 23, 2020, Tianwen-1 was successfully launched atop a Long March 5 rocket into Trans-Mars injection orbit.[145] The spacecraft, consisting of an orbiter, a lander, and a rover, aimed to achieve the goals of orbiting, landing, and roving on Mars in one single mission on the nation's first attempt. Due to its highly complex and risky nature, the mission was widely described as "ambitious" by international observers.[146][147][148][149][150]

After a seven-month journey, on February 10, 2021, Tianwen-1 entered Mars orbit and became China's first operational Mars probe.[151] The payloads on the orbiter were subsequently activated and started surveying Mars in preparation for the landing. In the following few months, CNSA released a series of images captured by the orbiter.[152][153] On April 24, CNSA announced that the first Chinese Mars rover carried by Tianwen-1 probe had been named Zhurong, the god of fire in ancient Chinese mythology.[154]

On May 15, 2020, around 1 am (Beijing time), Tianwen-1 initiated its landing process by igniting its main engines and lowering its orbit, followed by the separation of landing module at 4 am. The orbiter then returned to the parking orbit while the lander moved toward Mars atmosphere. Three hours later, the landing experienced the most dangerous atmospheric entry process that lasted for nine minutes. At 7:18 am, the lander successfully landed on the preselected southern Utopia Planitia.[155] On May 25, the Zhurong rover drove onto the Martian surface from the lander.[156] On June 11, CNSA released the first batch of high-resolution images of landing sites captured by Zhurong rovers, marking the success of the Mars landing mission.[157] Being China's first independent Mars mission, Tianwen-1 completed the daunting process involving the orbiting, landing, and roving in highly sophisticated manner on one single attempt, making China the second nation to land and drive a Mars rover on the Martian surface after the United States. It drew the attention of the world as another example of China's rapidly expanding presence in outer space.[155] Because of its huge difficulty and inspiring success, the Tianwen-1 development team received IAF World Space Award of 2022. It was the second time that a Chinese team awarded with this honor after the Chang'e-4 mission in 2019.[103]

On 13 March, China attempted to launch two spacecrafts, DRO-A and DRO-B, into distant retrograde orbit around the Moon. As an independent project, the mission was managed by Chinese Academy of Sciences instead of Chinese Lunar Exploration Program. However, the mission failed to reach the strived for orbit due to an upper stage malfunction, remaining stranded in low Earth orbit.[158][159] Rescue attempts had been made as its orbit had been observed being significantly raised to a highly elliptical orbit since its launch, yet the following status remains unknown to the public.[160] They appear to have succeeded in reaching their desired orbit.[161][162]

On 20 March 2024 China launched its relay satellite, Queqiao-2, in the orbit of the Moon, along with two mini satellites Tiandu 1 and 2. Queqiao-2 will relay communications for the Chang'e 6 (far side of the Moon), Chang'e 7 and Chang'e 8 (Lunar south pole region) spacecrafts. Tiandu 1 and 2 will test technologies for a future lunar navigation and positioning constellation.[163] All the three probes entered lunar orbit successfully on 24 March 2024 (Tiandu-1 and 2 were attached to each other and separated in lunar orbit on 3 April 2024).[164][165]

China sent Chang'e 6 on 3 May 2024, which conducted the first lunar sample return from Apollo Basin on the far side of the Moon.[166] This is China's second lunar sample return mission, the first was achieved by Chang'e 5 from the lunar near side four years earlier.[167] It also carried the Chinese Jinchan rover to conduct infrared spectroscopy of lunar surface and imaged Chang'e 6 lander on lunar surface.[168] The lander-ascender-rover combination was separated with the orbiter and returner before landing on 1 June 2024 at 22:23 UTC. It landed on the Moon's surface on 1 June 2024.[169][170] The ascender was launched back to lunar orbit on 3 June 2024 at 23:38 UTC, carrying samples collected by the lander, and later completed another robotic rendezvous and docking in lunar orbit. The sample container was then transferred to the returner, which landed in Inner Mongolia on 25 June 2024, completing China's far side extraterrestrial sample return mission. After dropping off the return samples for Earth, the Chang'e 6 (CE-6) orbiter was successfully captured by the Sun-Earth L2 Lagrange point on 9 September 2024.[171]

Near future development

[edit]

According to a 2022 government white paper, China will conduct more human spaceflight, lunar and planetary exploration missions, including:[172]

- Xuntian Space Telescope launch.

- Chang'e-7 mission to perform a precise landing in the Moon's polar region that includes a "hopping detector" to explore permanently shadowed areas.

- Chang'e-8 lunar polar mission to test in-situ resource utilization and establish the predicate for the International Lunar Research Station.

- Tianwen-2 mission to sample near-Earth asteroids and probe main-belt comets.

- Tianwen-3 mission using two launches to return samples from Mars.

- Tianwen-4 mission to explore the Jupiter system and Callisto; a probe to fly-by Uranus will be attached to the Jupiter probe.

In addition to these, China has also initiated the crewed lunar landing phase of its lunar exploration program, which aims to land Chinese astronauts on the Moon by 2030. A new crewed carrier rocket (Long March 10), new generation crew spacecraft, crewed lunar lander, lunar EVA spacesuit, lunar rover and other equipment are under development.[173][174]

CNSA's Tianwen-2 was launched in May 2025,[175] to explore the co-orbital near-Earth asteroid 469219 Kamoʻoalewa and the active asteroid 311P/PanSTARRS and collecting samples of the regolith of Kamo'oalewa.[176]

Chinese space program and the international community

[edit]Belt and Road Initiative

[edit]One of China's priorities in its Belt and Road Initiative is to improve satellite information pathways.[177]: 300

Bilateral space cooperation

[edit]

China is an attractive partner for space cooperation for other developing countries because it launches their satellites at a reduced cost and often provides financing in the form of policy loans.[177]: 301

With respect to the African countries, the 2022-2024 action plan for the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation commits China to using space technology to enhance cooperation with African countries and to create centers for Africa-China cooperation on satellite remote sensing application.[177]: 300 African countries are increasingly cooperating with China on satellite launches and specialized training.[177]: 301 As of 2022, China has launched two satellites for Ethiopia, two for Nigeria, one for Algeria, one for Sudan, and one for Egypt.[177]: 301–302

China and Namibia jointly operate the China Telemetry, Tracking, and Command Station which was established in 2001 in Swakopmund, Namibia.[177]: 304 This station tracks Chinese satellites and space missions.[177]: 304

China and Brazil have successfully cooperated in the field of space.[178]: 202 Among the most successful space cooperation projects were the development and launch of earth monitoring satellites.[178]: 202 As of 2023, the two countries have jointly developed six China-Brazil Earth Resource Satellites.[178]: 202 These projects have helped both Brazil and China develop their access to satellite imagery and promoted remote sending research.[178]: 202 Brazil and China's cooperation is a unique example of South-South cooperation between two developing countries in the field of space.[178]: 202

Dual-use technologies and outer space

[edit]The PRC is a member of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space and a signatory to all United Nations treaties and conventions on space, with the exception of the 1979 Moon Treaty.[179] The United States government has long been resistant to the use of PRC launch services by American industry due to concerns over alleged civilian technology transfer that could have dual-use military applications to countries such as North Korea, Iran or Syria. Thus, financial retaliatory measures have been taken on many occasions against several Chinese space companies.[180]

NASA's policy excluding Chinese state affiliates

[edit]The Cox Report, released in 1999, alleged that following decades of intelligence operations against U.S. weapons laboratories conducted by the Ministry of State Security, China stole design information regarding advanced thermonuclear weapons. In 2011, Congress passed a law prohibiting NASA researchers from working with Chinese citizens affiliated with a Chinese state enterprise or entity without FBI certification or using NASA funds to host Chinese visitors.[181] In March 2013, the U.S. Congress passed legislation barring Chinese nationals from entering NASA facilities without a waiver from NASA.[182]

The history of the U.S. exclusion policy can be traced back to the Cox Report's allegations that the technical information that American companies provided China for its commercial satellite ended up improving Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile technology.[183] This was further aggravated in 2007 when China blew up a defunct meteorological satellite in low Earth orbit to test a ground-based anti-satellite (ASAT) missile. The debris created by the explosion contributed to the space junk that litter Earth's orbit, exposing other nations' space assets to the risk of accidental collision.[183] The United States also fears the Chinese application of dual-use space technology for nefarious purposes.[184]

The Chinese response to the exclusion policy involved its own space policy of opening up its space station to the outside world, welcoming scientists coming from all countries.[184] American scientists have also boycotted NASA conferences due to its rejection of Chinese nationals in these events.[185] In September 2025, NASA prohibited Chinese nationals from working with its programs.[186]

Organization

[edit]Initially, the space program of the PRC was organized under the People's Liberation Army, particularly the Second Artillery Corps (now the PLA Rocket Force, PLARF). In the 1990s, the PRC reorganized the space program as part of a general reorganization of the defense industry to make it resemble Western defense procurement.

The China National Space Administration, an agency within the State Administration of Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, is now responsible for launches. The Long March rocket is produced by the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, and satellites are produced by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation. The latter organizations are state-owned enterprises; however, it is the intent of the PRC government that they should not be actively state-managed and that they should behave as independent design bureaus.[citation needed]

Universities and institutes

[edit]The space program also has close links with:

- College of Aerospace Science and Engineering, National University of Defense Technology

- School of Astronautics, Beihang University

- School of Aerospace, Tsinghua University

- School of Astronautics, Northwestern Polytechnical University

- School of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Zhejiang University

- Institute of Aerospace Science and Technology, Shanghai Jiaotong University

- College of Aeronautics, Harbin Institute of Technology

- School of Automation Science and Electrical Engineering, Beihang University

Space cities

[edit]- Dongfeng Space City (东风航天城), also known as Base 20 (二十基地) or Dongfeng base (东风基地)[187]

- Beijing Space City (北京航天城)

- Wenchang Space City (文昌航天城)

- Shanghai Space City (上海航天城)

- Yantai Space City (烟台航天城)[188][189]

- Guizhou Aerospace Industrial Park (贵州航天高新技术产业园), also known as Base 061 (航天〇六一基地), founded in 2002 after approval of Project 863 for industrialization of aerospace research centers (国家863计划成果产业化基地).[190]

Suborbital launch sites

[edit]- Nanhui (南汇县老港镇东进村) First successful launch of a T-7M sounding rocket on February 19, 1960.[191]

- Base 603 (安徽广德誓节渡中国科学院六〇三基地) Also known as Guangde Launch Site (广德发射场).[192] The first successful flight of a biological experimental sounding rocket transporting eight white mice was launched and recovered on July 19, 1964.[193]

Satellite launch centers

[edit]The PRC has 6 satellite launch centers/sites:

- Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center (JSLC)

- Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center (TSLC)

- Xichang Satellite Launch Center (XSLC)

- Wenchang Spacecraft Launch Site (administered by Xichang SLC)

- Wenchang Commercial Space Launch Site (administered by HICAL)

- Haiyang Oriental Aerospace Port (administered by Taiyuan SLC)

Monitoring and control centers

[edit]- Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Center (BACCC)

- Xi'an Satellite Control Center (XSCC) also known as Base 26(二十六基地)

- Fleet of six Yuanwang-class space tracking ships.[194]

- Data relay satellite (数据中继卫星) Tianlian I (天链一号), specially developed to decrease the communication time between the Shenzhou 7 spaceship and the ground; it will also improve the amount of data that can be transferred. The current orbit coverage of 12 percent will thus be increased to a total of about 60 percent.[195][196]

- Deep Space Tracking Network composed with radio antennas in Beijing, Shanghai, Kunming and Ürümqi, forming a 3000 km VLBI (甚长基线干涉).[197]

Domestic tracking stations

[edit]- New integrated land-based space monitoring and control network stations, forming a large triangle with Kashi in the north-west of China, Jiamusi in the north-east and Sanya in the south.[198]

- Weinan Station

- Changchun Station

- Qingdao Station

- Zhanyi Station

- Nanhai Station

- Tianshan Station

- Xiamen Station

- Lushan Station

- Jiamusi Station

- Dongfeng Station

- Hetian Station

Overseas tracking stations

[edit]- Tarawa Station, Kiribati

- Malindi Station, Kenya

- Swakopmund tracking station, Namibia

- China Satellite Launch and Tracking Control General tracking hub at Espacio Lejano Station in Neuquén Province, Argentina.[199] 38°11′35″S 70°08′51″W / 38.193014°S 70.147581°W

Plus shared space tracking facilities with France, Brazil, Sweden, and Australia.

Crewed landing sites

[edit]Notable spaceflight programs

[edit]Project 714

[edit]As the Space Race between the two superpowers reached its climax with humans landing on the Moon, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai decided on July 14, 1967, that the PRC should not be left behind, and therefore initiated China's own crewed space program. The top-secret Project 714 aimed to put two people into space by 1973 with the Shuguang spacecraft. Nineteen PLAAF pilots were selected for this goal in March 1971. The Shuguang-1 spacecraft to be launched with the CZ-2A rocket was designed to carry a crew of two. The program was officially cancelled on May 13, 1972, for economic reasons, though the internal politics of the Cultural Revolution likely motivated the closure.[citation needed]

The short-lived second crewed program was based on the successful implementation of landing technology (third in the World after USSR and United States) by FSW satellites. It was announced a few times in 1978 with the open publishing of some details including photos, but then was abruptly canceled in 1980. It has been argued that the second crewed program was created solely for propaganda purposes, and was never intended to produce results.[200]

Project 863

[edit]A new crewed space program was proposed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences in March 1986, as Astronautics plan 863-2. This consisted of a crewed spacecraft (Project 863–204) used to ferry astronaut crews to a space station (Project 863–205). In September of that year, astronauts in training were presented by the Chinese media. The various proposed crewed spacecraft were mostly spaceplanes. Project 863 ultimately evolved into the 1992 Project 921.[citation needed]

China Manned Space Program (Project 921)

[edit]Spacecraft

[edit]

In 1992, authorization and funding were given for the first phase of Project 921, which was a plan to launch a crewed spacecraft. The Shenzhou program had four uncrewed test flights and two crewed missions. The first one was Shenzhou 1 on November 20, 1999. On January 9, 2001 Shenzhou 2 launched carrying test animals. Shenzhou 3 and Shenzhou 4 were launched in 2002, carrying test dummies. Following these was the successful Shenzhou 5, China's first crewed mission in space on October 15, 2003, which carried Yang Liwei in orbit for 21 hours and made China the third nation to launch a human into orbit. Shenzhou 6 followed two years later ending the first phase of Project 921. Missions are launched on the Long March 2F rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) of the Equipment Development Department of the Central Military Commission provides engineering and administrative support for the crewed Shenzhou missions.[201]

Space laboratory

[edit]The second phase of the Project 921 started with Shenzhou 7, China's first spacewalk mission. Then, two crewed missions were planned to the first Chinese space laboratory. The PRC initially designed the Shenzhou spacecraft with docking technologies imported from Russia, therefore compatible with the International Space Station (ISS). On September 29, 2011, China launched Tiangong 1. This target module is intended to be the first step to testing the technology required for a planned space station.

On October 31, 2011, a Long March 2F rocket lifted the Shenzhou 8 uncrewed spacecraft which docked twice with the Tiangong 1 module. The Shenzhou 9 craft took off on 16 June 2012 with a crew of 3. It successfully docked with the Tiangong-1 laboratory on 18 June 2012, at 06:07 UTC, marking China's first crewed spacecraft docking.[202] Another crewed mission, Shenzhou 10, launched on 11 June 2013. The Tiangong 1 target module is then expected to be deorbited.[203]

A second space lab, Tiangong 2, launched on 15 September 2016, 22:04:09 (UTC+8).[204] The launch mass was 8,600 kg, with a length of 10.4m and a width of 3.35m, much like the Tiangong 1.[205] Shenzhou 11 launched and rendezvoused with Tiangong 2 in October 2016, with an unconfirmed further mission Shenzhou 12 in the future. The Tiangong 2 brings with it the POLAR gamma ray burst detector, a space-Earth quantum key distribution, and laser communications experiment to be used in conjunction with the Mozi 'Quantum Science Satellite', a liquid bridge thermocapillary convection experiment, and a space material experiment. Also included is a stereoscopic microwave altimeter, a space plant growth experiment, and a multi-angle wide-spectral imager and multi-spectral limb imaging spectrometer. Onboard TG-2 there will also be the world's first-ever in-space cold atomic fountain clock.[205]

Space station

[edit]A larger basic permanent space station (基本型空间站) would be the third and last phase of Project 921. This will be a modular design with an eventual weight of around 60 tons, to be completed sometime before 2022. The first section, designated Tiangong 3, was scheduled for launch after Tiangong 2,[206] but ultimately not ordered after its goals were merged with Tiangong 2.[207]

This could also be the beginning of China's crewed international cooperation, the existence of which was officially disclosed for the first time after the launch of Shenzhou 7.[208]

The first module of Tiangong space station, Tianhe core module, was launched on 29 April 2021, from Wenchang Space Launch Site.[116] It was first visited by Shenzhou 12 crew on 17 June 2021. The Chinese space station is scheduled to be completed in 2022[209] and fully operational by 2023.

Lunar exploration

[edit]

In January 2004, the PRC formally started the implementation phase of its uncrewed Moon exploration project. According to Sun Laiyan, administrator of the China National Space Administration, the project will involve three phases: orbiting the Moon; landing; and returning samples.[citation needed]

On December 14, 2005, it was reported "an effort to launch lunar orbiting satellites will be supplanted in 2007 by a program aimed at accomplishing an uncrewed lunar landing. A program to return uncrewed space vehicles from the Moon will begin in 2012 and last for five years, until the crewed program gets underway" in 2017, with a crewed Moon landing planned after that.[210]

The decision to develop a new Moon rocket in the 1962 Soviet UR-700M-class (Project Aelita) able to launch a 500-ton payload in LTO[dubious – discuss] and a more modest 50 tons LTO payload LV has been discussed in a 2006 conference by academician Zhang Guitian (张贵田), a liquid propellant rocket engine specialist, who developed the CZ-2 and CZ-4A rockets engines.[211][212][213]

On June 22, 2006, Long Lehao, deputy chief architect of the lunar probe project, laid out a schedule for China's lunar exploration. He set 2024 as the date of China's first moonwalk.[214]

In September 2010, it was announced that the country is planning to carry out explorations in deep space by sending a man to the Moon by 2025. China also hoped to bring a Moon rock sample back to Earth in 2017, and subsequently build an observatory on the Moon's surface. Ye Peijian, Commander in Chief of the Chang'e program and an academic at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, added that China has the "full capacity to accomplish Mars exploration by 2013."[215][216]

On December 14, 2013[217] China's Chang'e 3 became the first object to soft-land on the Moon since Luna 24 in 1976.[218]

On 20 May 2018, several months before the Chang'e 4 mission, the Queqiao was launched from Xichang Satellite Launch Center in China, on a Long March 4C rocket.[219] The spacecraft took 24 days to reach L2, using a gravity assist at the Moon to save propellant.[220] On 14 June 2018, Queqiao finished its final adjustment burn and entered the mission orbit, about 65,000 kilometres (40,000 mi) from the Moon. This is the first lunar relay satellite ever placed in this location.[220]

On January 3, 2019, Chang'e 4, the China National Space Administration's lunar rover, made the first-ever soft landing on the Moon's far side. The rover was able to transmit data back to Earth despite the lack of radio frequencies on the far side, via a dedicated satellite sent earlier to orbit the Moon. Landing and data transmission are considered landmark achievements for human space exploration.[221]

Yang Liwei declared at the 16th Human in Space Symposium of International Academy of Astronautics (IAA) in Beijing, on May 22, 2007, that building a lunar base was a crucial step to realize a flight to Mars and farther planets.[222]

According to practice, since the whole project is only at a very early preparatory research phase, no official crewed Moon program has been announced yet by the authorities. But its existence is nonetheless revealed by regular intentional leaks in the media.[223] A typical example is the Lunar Roving Vehicle (月球车) that was shown on a Chinese TV channel (东方卫视) during the 2008 May Day celebrations.

On 23 November 2020, China launched the new Moon mission Chang'e 5, which returned to Earth carrying lunar samples on 16 December 2020. Only two nations, the United States and the former Soviet Union have ever returned materials from the Moon, thus making China the third country to have ever achieved the feat.[224]

China sent Chang'e 6 on 3 May, which conducted the first lunar sample return from the far side of the Moon.[166] This is China's second lunar sample return mission, the first was achieved by Chang'e 5 from the lunar near side 4 years ago.[167]

Mission to Mars and beyond

[edit]

In 2006, the Chief Designer of the Shenzhou spacecraft stated in an interview that:

搞航天工程不是要达成升空之旅, 而是要让人可以正常在太空中工作, 为将来探索火星、土星等作好准备。 Space programs are not aimed at sending humans into space per se, but instead at enabling humans to work normally in space, and prepare for the future exploration of Mars, Saturn, and beyond.

Sun Laiyan, administrator of the China National Space Administration, said on July 20, 2006, that China would start deep space exploration focusing on Mars over the next five years, during the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2006–2010) Program period.[226] In April 2020, the Planetary Exploration of China program was announced. The program aims to explore planets of the Solar System, starting with Mars, then expanded to include asteroids and comets, Jupiter and more in the future.[227]