Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Maritime Silk Road

View on Wikipedia

The Maritime Silk Road or Maritime Silk Route is the maritime section of the historic Silk Road that connected Southeast Asia, East Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian Peninsula, eastern Africa, and Europe. It began by the 2nd century BCE and flourished until the 15th century CE.[2] The Maritime Silk Road was primarily established and operated by Austronesian sailors in Southeast Asia who sailed large long-distance ocean-going sewn-plank and lashed-lug trade ships.[3]: 11 [4] The route was also utilized by the dhows of the Persian and Arab traders in the Arabian Sea and beyond,[3]: 13 and the Tamil merchants in South Asia.[3]: 13 China also started building their own trade ships (chuán) and followed the routes in the later period, from the 10th to the 15th centuries CE.[5][6]

The network followed the footsteps of older Austronesian jade maritime networks in Southeast Asia,[7][8][9][10] as well as the maritime spice networks between Southeast Asia and South Asia, and the West Asian maritime networks in the Arabian Sea and beyond, coinciding with these ancient maritime trade roads by the current era.[11][12][13]

The term "Maritime Silk Road" is a modern name, acquired from its similarity to the overland Silk Road. Overland Silk Road was itself a modern name, the idea of which was invented as late as 1877 by a Prussian geographer, Baron von Richthofen while he engaged in a geological survey of China for connecting China with Germany through railways, and the term "Silk Road" only entered the English language in 1938 with the publication of a popular book by Swedish explorer Sven Hedin.[14] The ancient maritime routes through the Indo-West Pacific (Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean) had no particular name for the majority of its very long history.[3] Despite the modern name, the Maritime Silk Road involved exchanges in a wide variety of goods over a very wide region, not just silk or Asian exports.[6][15]

History

[edit]Precursor prehistoric maritime networks

[edit]

The Maritime Silk Road developed from the earlier Neolithic lingling-o jade maritime trade networks established by Austronesians in Southeast Asia. This extensive ancient maritime trade network in Southeast Asia, covering a 3000-kilometer area around the South China Sea, existed long before the Maritime Silk Road.[16] It lasted for around 3,000 years, partially overlapping with the Maritime Silk Road, from 2000 BCE to 1000 CE. It was initially established by the indigenous peoples of Taiwan and the northern Philippines. Raw nephrite jade (Fengtian jade) was sourced from deposits in eastern Taiwan and worked into ornaments and tools in the Philippines (the most notable and most numerous of are double-headed pendants and penannular earrings known as lingling-o). This network later included southern Vietnam (the Sa Huỳnh culture), Borneo, eastern peninsular Malaysia, eastern Cambodia, peninsular Thailand, and other areas in Southeast Asia where these jade ornaments, along with other trade goods, were manufactured and exchanged (also known as the Sa Huynh-Kalanay Interaction Sphere). Taiwan-sourced jade declined in use after around 500 BCE, and non-Taiwanese jade and other materials became more common.[16][7][8][9][10] The distribution of these jade artifacts were also accompanied by other evidence of maritime trade and shared material culture particularly between the Austronesians of the Neolithic Philippines, southern Vietnam, and Borneo.[16]

The wide distribution throughout Island Southeast Asia of the ceremonial bronze drums (c. 600 BCE to 400 CE) sourced from the Dong Son culture of northern Vietnam is also evidence of the antiquity and density of this prehistoric Southeast Asian maritime network.[3]

During the operation of the maritime trade in jade artifacts, the Austronesian spice trade networks were also established by Islander Southeast Asians with Sri Lanka and Southern India by around 1500 to 600 BCE.[17][18][11][12] These early contacts resulted in the introduction of Austronesian crops and material culture to South Asia,[18] including betel nut chewing, coconuts, sandalwood, domesticated bananas,[18][17] sugarcane,[19] cloves, and nutmeg.[20] It also introduced Austronesian sailing technologies like outrigger boats which are still utilized in Sri Lanka and southern India.[12][18] Semi-precious stone and glass ornaments showing northern Indian designs have also been recovered from the Khao Sam Kaeo (c. 400-100 BCE) and Ban Don Ta Phet (c. 24 BCE to 276 CE) archaeological sites in Thailand, along with trade goods from the Austronesian Sa Huynh-Kalanay Interaction Sphere. Both sites are coastal settlements and part of the jade trade network, indicating that the maritime routes of Austronesians had already reached South Asia by this period.[3][21][15] South Asian crops like the mung bean and horsegram were also present in Khao Sam Kaeo, indicating the exchange was reciprocal.[18] There is also indirect evidence of very early Austronesian contacts with Africa, based on the presence and spread of Austronesian domesticates like bananas, taro, chickens, and purple yam in Africa in the first millennium BCE.[18]

The western circuit of the Maritime Silk Road also developed from earlier maritime trade routes in West Asia. These linked Sri Lanka, the Malabar Coast of India, Persia, Mesopotamia, Arabia, Egypt, the Horn of Africa, and the Greco-Roman civilizations in the Mediterranean. These trade routes (initially only near-coastal, short-range, and small-scale) has existed since the Neolithic, from at least the Ubaid period (c. 5000 BCE) of Mesopotamia. They became regular trade routes between urban centers in West Asia by the first millennium BCE.[6][18][13]

Maritime Silk Road

[edit]By around the 2nd century BCE, the prehistoric Austronesian jade and spice trade networks in Southeast Asia fully connected with the maritime trade routes of South Asia, the Middle East, eastern Africa, and the Mediterranean, becoming what is now known as the Maritime Silk Road. Prior to the 10th century, the eastern part of the route was primarily used by Southeast Asian Austronesian traders using distinctive sewn-plank and lashed-lug ships, although Persian and Tamil traders also sailed the western parts of the routes.[3][13] It allowed the exchange of goods from East and Southeast Asia on one end, all the way to Europe and eastern Africa on the other.[1][13]

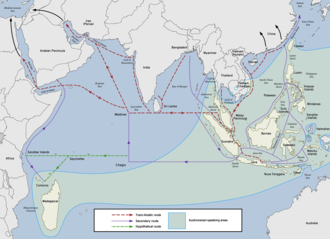

Austronesian thalassocracies controlled the flow of trade in the eastern regions of the Maritime Silk Road, especially the polities around the straits of Malacca and Bangka, the Malay Peninsula, and the Mekong Delta; through which passed the main routes of the Austronesian trade ships to Giao Chỉ (in the Tonkin Gulf) and Guangzhou (southern China), the endpoints (later also including Quanzhou by the 10th century CE). Chinese records misidentified these kingdoms as being "Indian" due to the Indianization of these regions.[3] Secondary routes also passed through the coastlines of the Gulf of Thailand;[1][22] as well as through the Java Sea, Celebes Sea, Banda Sea, and the Sulu Sea, reconnecting with the main route through the northern Philippines and Taiwan. The secondary routes also continue onward to the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea for a limited extent.[1] Glass artifacts from India and Egypt that passed through glassworkers in Southeast Asian and South Asian ports have been recovered from graves in the Korean peninsula (c. 2nd-6th centuries CE), showing the furthest northeastern extent of the Maritime Silk Road.[15]

The main route of the western regions of the Maritime Silk Road directly crosses the Indian Ocean from the northern tip of Sumatra (or through the Sunda Strait) to Sri Lanka, southern India and Bangladesh, and the Maldives. It branches from here into routes through the Arabian Sea entering the Gulf of Oman (into the Persian Gulf), and the Gulf of Aden (into the Red Sea). Secondary routes also pass through the coastlines of the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, and southwards along the coast of East Africa to Zanzibar, the Comoros, Madagascar, and the Seychelles.[1][23] The Maldives was of particular importance as a major hub for Austronesian sailors venturing through the western routes.[1]

The route was influential in the early spread of Hinduism and Buddhism to the east.[24][25] The close links of these religions to trade with South Asia led to the widespread adoption of Sanskrit as the trade lingua franca in the early Maritime Silk Road by the 4th century CE.[3] Han and Tang dynasty Chinese records also indicate that the early Chinese Buddhist pilgrims to South Asia booked passage with the Austronesian ships (which they called the k'un-lun po) that traded in the Chinese port city of Guangzhou. Books written by Chinese monks like Wan Chen and Hui-Lin contain detailed accounts of the large trading vessels from Southeast Asia dating back to at least the 3rd century CE.[26]

Austronesians were already sailing as far as East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula even during the earlier period.[27] Austronesians colonized the island of Madagascar off the coast of Africa some time in between the 1st century CE to the 6th or 7th centuries CE.[27][28][29] It remained a part of the Maritime Silk Road, along with the nearby African, Arab, and Persian trading ports of Kilwa Kisiwani and Zanzibar (Tanzania), and other ports along the mainland coasts of modern Somalia, Kenya, and Mozambique.[30] Records from Portuguese explorers in the late 15th and early 16th centuries indicate that direct maritime links between Indonesia and Madagascar persisted up until shortly before the colonial period.[1]

Srivijaya, a Hindu-Buddhist Austronesian polity founded at Palembang in 682 CE, rose to dominate the trade in the region around the straits of Malacca and Sunda and the South China Sea emporium by controlling the trade in luxury aromatics and Buddhist artifacts from West Asia to a thriving Tang market.[3]: 12 It emerged through the conquest and subjugation of neighboring thalassocracies. These included Melayu, Kedah, Tarumanagara, and Mataram, among others. These polities controlled the sea lanes in Southeast Asia and exploited the spice trade of the Spice Islands, as well as maritime trade-routes between India and China.[31]

By the 7th century CE, Arab dhow traders also ventured into the routes earlier pioneered by Persian traders to Sri Lanka, coinciding with the spread of Islam throughout West Asia. They pushed deeper east into Srivijaya and Guangzhou, leading to the earliest spread of Islam into Southeast Asian polities. During this period, the Persian language (Fārsī), became the dominant lingua franca of both the Maritime and overland Silk Road.[3][32]

The Butuan boat burials of the Philippines, which feature eleven lashed-lug boat remains of the Austronesian boatbuilding traditions (individually dated from 689 CE to 988 CE), were found in association with large amounts of trade goods from China, Cambodia, Thailand (Haripunjaya and Satingpra), Vietnam, and as far as Persia, indicating they traded as far as the Middle East.[33][34][35]

By the 10th to 13th centuries, there was an economic boom in maritime trade, led primarily by the fact that the Song dynasty of China started building its own trading ships (chuán) capable of sailing sea routes. The Song court also loosened restrictions on private trade, despite the traditional Chinese Confucian disdain for trade.[3] This was partly due to the loss of access by the Song dynasty to the overland Silk Road.[3] Song maritime technology was developed from observing Southeast Asian Austronesian ships. Before this, Chinese ships were essentially fluvial (riverine) in nature and operation and were not seaworthy.[36][4]

The Song started sending trading expeditions to the region they referred to as Nan hai (Chinese: 南海; pinyin: Nánhǎi; lit. 'South Seas'), mostly still dominated by Srivijaya, venturing as far south as the Sulu Sea and the Java Sea. This led to the establishment of new trading ports in Southeast Asia (like in Java and Sumatra) that specifically catered to the Chinese demand for goods like "dragon's brain perfume" (camphor) and other exotica. Quanzhou also became a major Chinese trading port during this period, joining the older trading port of Guangzhou. Both became tightly linked to their Southeast Asian counterparts, leading historians to characterize the distinct trading circuit in this region as the "Asian Mediterranean", from its similarity to the Mediterranean Sea Trade.[3] However, the Song enacted a 9-month limit on how long trade ships can stay at sea, limiting the range of Chinese trade ships to Southeast Asia.[5][37]

Arab and Tamil traders also increased their participation with direct trade to Chinese ports through the Strait of Malacca in the 10th to 13th centuries. The surprise naval expeditions in 1025 of Rajendra I of the Tamil Chola Empire against Srivijaya's ports along the strait, may have been motivated by Srivijaya's attempt to regulate or block Tamil trading guilds.[3] The Chola invasions ended Srivijaya's monopoly on the Strait of Malacca routes for around a century, during which many of the Srivijayan cities were occupied by the Chola. Srivijaya was left greatly weakened and was eventually subjugated by Singhasari by around 1275, before finally being absorbed by the successor thalassocracy of Majapahit (1293–1527).[38][39]

China was invaded by the Mongol Yuan dynasty in the 13th century. Chinese shipping during this period was monopolized by the state, via foreign Muslim merchants partnered with the Yuan government in ortogh relationships. Though unlike the Song, the Yuan lifted the 9-month limit, allowing Chinese trade to venture as far as South Asia. The Yuan also attempted naval invasions on Japan, Majapahit, and Vietnam (Austronesian Champa, and Kinh Đại Việt). All of which failed.[5][37] China itself was later devastated by floods, drought, and famine. Concurrently, the Black Death was sweeping through Europe and Western Asia. All of these factors led to a slump in trade along the Maritime Silk Road in the 14th century.[3]

In the late 14th century, the city-state of Palembang (the former capital of Srivijaya, which has since Islamized) sent an envoy to the Hongwu Emperor, the first emperor of the Ming dynasty (which overthrew the Yuan), to reestablish trade routes. The ruler of Palembang was hoping to regain the city's former wealth, independent of the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit. Hayam Wuruk of Majapahit, angry at the actions of the vassal state, sent a punitive naval attack on Palembang in 1377, causing a diaspora of princes and nobles to the Kingdom of Singapura. Singapura, in turn, was attacked and sacked in 1398. Parameswara, originally from Palembang and the last ruler of Singapura, fled to the western coast of the Malay Peninsula and founded the Muslim Sultanate of Malacca in the early 15th century.[40]

During the same period in the early 15th century, the Ming dynasty launched the expeditions of Zheng He, with the goal of forcing the "barbarian kings" of Southeast Asia to resume sending "tribute" (i.e. regular trade routes) to the Ming court. This was typical of the Sinocentric views at the time of viewing "trade as tribute". Zheng He's expeditions were short-lived, as the drain in imperial funds and the threat of invasion from the north led the Xuande Emperor to cease the expeditions. He enacted the hai jin laws shortly after, and banned outgoing trade altogether. Although ultimately, Zheng He's expeditions were successful in their goal of restoring trade relations with Southeast Asia (in this case, Malacca) and the Ming dynasty.[3] By the mid-15th century, the Sultanate of Malacca had gained effective control of the Strait of Malacca. Further weakening Majapahit's influence greatly, which was already suffering from internal rebellions.[41] Trade from Malacca continued to arrive in Chinese ports in the brief period prior to the fall of Majapahit, the Portuguese invasion of Malacca, and the fall of the Ming dynasty to the Manchu invasions.[3][5][37][42]

Decline

[edit]

The Maritime Silk Route was disrupted by the colonial era in the 15th century, essentially being replaced with European trade routes. Shipbuilding of the formerly dominant Southeast Asian trading ships (jong, the source of the English term "junk") declined until it ceased entirely by the 17th century. Although Chinese-built chuán survived until modern times.[3][43][4] There was new demand for spices from Southeast Asia and textiles from India and China, but these were now linked with direct trade routes to the European market, instead of passing through regional ports.[3]

By the 16th century, the Age of Exploration had begun. The Portuguese Empire's capture of Malacca led to the transfer of the trade centers to the sultanates of Aceh and Johor. The Spanish Empire in the Philippines established the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade, which acquired trade goods like Chinaware and silk from Quanzhou and Zhangzhou, and spices (mostly from the Spice Islands of Moluccas) for the markets in Latin America and Europe. All of which were traded over the Pacific to Acapulco in Mexico and throughout the Spanish Americas; and also later traded via the Flota de Indias (Spanish treasure fleet) from Veracruz in Mexico to Seville in Spain and onward throughout Europe. The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade route was the first permanent trade route across the Pacific. Similarly, the West Indies Spanish treasure fleet was the first permanent transatlantic trade route in history. Both bypassed the Indian Ocean Maritime Silk Road entirely.[3]

Archaeology

[edit]

The archaeological evidence of the Maritime Silk Road include numerous shipwrecks recovered along the route carrying (or associated with) trade goods sourced from various far-flung ports. The origins of these early ships are readily identifiable by a combination of distinctive features and shipbuilding techniques used (such as lashed-lug and sewn boat traditions).[37][4] These include the Pontian boat (c. 260–430 CE),[3] the Punjulharjo boat (c. 660-780 CE),[44] the Butuan ship burials (multiple boats ranging from c. 689 to 988 CE),[35][45] the Chau Tan shipwreck (c. late 8th to early 9th century CE),[44] the Intan wreck (c. early to mid-10th century CE),[3] the Karawang shipwreck (c. 10th century CE),[44] and the Cirebon wreck (c. late 10th century CE), among others.[3]: 12 [46][47][48][36]

Almost all of the ships recovered from Southeast Asia before the 10th century belong to the Austronesian shipbuilding traditions, displaying variations and combinations of sewn-plank and lashed-lug techniques. Another early partial shipwreck, the Pak Klong Kluay shipwreck (c. 2nd century CE), uniquely joined planks using pegged mortise and tenon joints. Though this is similar to Phoenician and later Greco-Roman shipbuilding techniques, the ship is also Austronesian, with timber sourced locally from Southeast Asian trees and evidence of lashed-lug techniques on the inner surface. Some authors have pointed to this as evidence that the Phoenician mortise and tenon shipbuilding techniques originally developed outside of the Mediterranean.[44]

Only two shipwrecks recovered from Southeast Asia prior to the 10th century CE are not Austronesian and exhibit early Arab dhow shipbuilding techniques: the Phanom-Surin ship (c. 7th century CE) and the Belitung shipwreck (c. 826 CE),[36][44] Dhows similarly use sewn-plank techniques, but differ from Austronesian sewn-plank techniques in which the stitches are only visible from the inner surfaces and are discontinuous. They also did not originally use lashed-lug techniques, though later ships like the Belitung shipwreck adopted it from contact with Austronesian shipbuilders.[36] Some of the timber used on the major components of the Phanom-Surin ship is also sourced from Southeast Asian trees, despite its West Asian construction.[44] Similarly, some of the later Austronesian ships display elements of West Asian shipbuilding techniques (like cross-armed anchors) suggesting that the merchants and crew of the ships had multinational origins, regardless of where the ships were originally built.[44]

China did not start building sea-going ships that ventured into the Maritime Silk Road until the Song dynasty (c. 10th century CE).[3][5][36][44] The earliest known Chinese shipwrecks found along the Maritime Silk Road are the Ming-era Turiang wreck (c. 1305-1370 CE) and the Bakau wreck (c. early 15th century CE).[3][49][50] Chinese-built ships (chuán) are also readily identifiable by being built with iron nails and clamps, in contrast to Austronesian and Western Asian ships which were built entirely with wood joining and fiber lashings. Other distinctive features of Chinese ships which developed from their earlier fluvial (riverine) ship technologies include a flat-bottomed design (the keel was absent), a central rudder (instead of two side-mounted quarter rudders), and the division of the hull into water-tight compartments.[4] By around the end of the Maritime Silk Road in the 14th and 15th century, ships that combined features of both Chinese and Austronesian boatbuilding traditions also start to appear, even reaching as far as India.[36][44]

Indian ships are similarly absent in the archaeological context in the eastern routes of the Maritime Silk Road prior to the 10th century CE.[3]: 10 The Godavaya shipwreck (c. 2nd century CE) is the earliest evidence of maritime networking in the Indian Ocean, but it only involved local exchanges in raw materials along the South Indian coast.[44]

The archaeological evidence demonstrates that the trading ships in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean were Austronesian sewn-plank and lashed-lug vessels and Arab dhows prior to the 10th century CE. Austronesian vessels dominated the long-distance maritime trade for much of the history of the Maritime Silk Road.[3]: 10 [43]

Chinese ceramics are also valuable archaeological markers of the Maritime Silk Road due to their relative indestructibility and the fact that they can be precisely dated. They first entered Southeast Asia via the ancient Austronesian maritime networks in the 2nd century BCE but were not initially a major export of China. They became exported by the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), rapidly increased in volume during the Song (960-1279 CE) and Yuan dynasties (1279-1367 CE), before declining in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1643 CE), and ceasing entirely in the 15th century. Their distribution throughout the Southeast Asian trade network is uneven, reflecting differences in local demand, buying power, and trade specialization. The largest concentrations of Chinese ceramics are found along the Strait of Melaka and Java, with other significant concentrations in Sulawesi, Borneo, the Riau Archipelago, and the Philippines.[51]

Extent

[edit]Although usually spoken of in modern times in the context of the Eurocentric and Sinocentric demand for luxury goods and exotica by the Roman and Chinese empires (hence the fixation on silk in its name), the goods carried by the trading ships varied by which product was in demand by region and port.[3][6] They included ceramics, glass, beads, gems, ivory, fragrant wood, metals (both raw and finished goods), textiles (including silk), food (including grain, wine, and spices), aromatics, and animals, among others.[6] Ivory, in particular, was a significant export of east Africa (originating from overland trade routes through the African interior), leading Chirikure (2022) to label the western leg of the trade route as the "Maritime Ivory Route".[23]

It was also not small-scale trade or high value-low volume trade as some earlier historians had assumed. The goods carried by recovered shipwrecks show that they engaged in merchant capitalism. A very large number of goods, often mass-produced, were traded along the route.[3][52]

The trade route encompassed numbers of seas and ocean; including South China Sea, Strait of Malacca, Indian Ocean, Gulf of Bengal, Arabian Sea, Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. The maritime route overlaps with historic Southeast Asian maritime trade, spice trade, Indian Ocean trade and after 8th century—the Arabian naval trade network. The network also extend eastward to the East China Sea and the Yellow Sea to connect China with the Korean Peninsula and the Japanese archipelago.[1][3]

The Maritime Silk Road differed significantly in several aspects from the overland Silk Road, from where it acquired its name, and thus should not be viewed as a mere extension of it. Traders traveling through the Maritime Silk Road could span the entire distance of the maritime routes, instead of through regional relays as with the overland route. Ships could carry far larger amounts of goods, creating greater economic impact with each exchange. Goods carried by the ships also differed from goods carried by caravans. Traders on the maritime route faced different perils like weather and piracy, but they were not affected by political instability and could simply avoid areas in conflict.[6]

World Heritage nomination

[edit]In May 2017, experts from various fields held a meeting in London to discuss the proposal to nominate "Maritime Silk Route" as a new UNESCO World Heritage Site.[53]

Politicization

[edit]The academic research on the ancient Maritime Silk Road has been appropriated and mythologized by modern countries for political reasons. China, in particular, uses a mythologized image of the Maritime Silk Road for its Belt and Road Initiative, first proposed by General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping during a visit to Indonesia in 2015. It attempts to reconnect the old trade routes between the port cities of Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, and assumes erroneously that Chinese sailors played a major role in developing the route.[3]

India has also mythologized the Maritime Silk Road with Project Mausam, launched in 2014, which similarly attempts to reconnect old trade links with surrounding countries in the Indian Ocean. India also portrays itself as playing a central role in the Maritime Silk Road, and early Indian nationalist historians often depicted its trade connections and the overwhelmingly one way cultural diffusion as "Indian colonizaton" under the vision of a Greater India.[3][14][54][55]

See also

[edit]- Ancient maritime history

- Belitung shipwreck

- Cirebon shipwreck

- Indian Ocean trade

- Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

- List of ports and harbours of the Indian Ocean

- Maritime Silk Route Museum, Guangdong Province, China

- Tapayan

- Spice trade

- Indian Ocean slave trade

- String of Pearls (Indian Ocean)

- 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 978-3-319-33822-4.

- ^ "Maritime Silk Road". SEAArch. Archived from the original on 2014-01-05. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Guan, Kwa Chong (2016). "The Maritime Silk Road: History of an Idea" (PDF). NSC Working Paper (23): 1–30.

- ^ a b c d e Manguin, Pierre-Yves (September 1980). "The Southeast Asian Ship: An Historical Approach". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 11 (2): 266–276. doi:10.1017/S002246340000446X.

- ^ a b c d e Flecker, Michael (August 2015). "Early Voyaging in the South China Sea: Implications on Territorial Claims". Nalanda-Sriwijaya Center Working Paper Series. 19: 1–53.

- ^ a b c d e f Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (2022). "The Maritime Silk Road: An Introduction". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 11–26. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ a b Tsang, Cheng-hwa (2000). "Recent advances in the Iron Age archaeology of Taiwan". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 20: 153–158. doi:10.7152/bippa.v20i0.11751 (inactive 12 July 2025). ISSN 1835-1794.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ a b Turton, M. (17 May 2021). "Notes from central Taiwan: Our brother to the south". Taipei Times. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b Everington, K. (6 September 2017). "Birthplace of Austronesians is Taiwan, capital was Taitung: Scholar". Taiwan News. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ a b Bellwood, Peter; Hung, H.; Lizuka, Yoshiyuki (2011). "Taiwan Jade in the Philippines: 3,000 Years of Trade and Long-distance Interaction". In Benitez-Johannot, P. (ed.). Paths of Origins: The Austronesian Heritage in the Collections of the National Museum of the Philippines, the Museum Nasional Indonesia, and the Netherlands Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde. ArtPostAsia. ISBN 978-971-94292-0-3.

- ^ a b Bellina, Bérénice (2014). "Southeast Asia and the Early Maritime Silk Road". In Guy, John (ed.). Lost Kingdoms of Early Southeast Asia: Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture 5th to 8th century. Yale University Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-1-58839-524-5.

- ^ a b c Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. Vol. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0-415-10054-0.

- ^ a b c d de Saxcé, Ariane (2022). "Networks and Cultural Mapping of South Asian Maritime Trade". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 129–148. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ a b Dalrymple, William (2024). The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World (First ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4088-6444-9.

- ^ a b c Lankton, James W. (2022). "From Regional to Global: Early Glass and the Development of the Maritime Silk Road". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 71–96. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ a b c d Hung, Hsiao-Chun; Iizuka, Yoshiyuki; Bellwood, Peter; Nguyen, Kim Dung; Bellina, Bérénice; Silapanth, Praon; Dizon, Eusebio; Santiago, Rey; Datan, Ipoi; Manton, Jonathan H. (11 December 2007). "Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (50): 19745–19750. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707304104. PMC 2148369.

- ^ a b Zumbroich, Thomas J. (2007–2008). "The origin and diffusion of betel chewing: a synthesis of evidence from South Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond". eJournal of Indian Medicine. 1: 87–140. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fuller, Dorian Q.; Boivin, Nicole; Castillo, Cristina Cobo; Hoogervorst, Tom; Allaby, Robin G. (2015). "The archaeobiology of Indian Ocean translocations: Current outlines of cultural exchanges by proto-historic seafarers". In Tripati, Sila (ed.). Maritime Contacts of the Past: Deciphering Connections Amongst Communities. Delhi: Kaveri Books. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-81-926244-3-3.

- ^ Daniels, Christian; Menzies, Nicholas K. (1996). Needham, Joseph (ed.). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 3, Agro-Industries and Forestry. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177–185. ISBN 978-0-521-41999-4.

- ^ Olivera, Baldomero; Hall, Zach; Granberg, Bertrand (31 March 2024). "Reconstructing Philippine history before 1521: the Kalaga Putuan Crescent and the Austronesian maritime trade network". SciEnggJ. 17 (1): 71–85. doi:10.54645/2024171ZAK-61.

- ^ Glover, Ian C.; Bellina, Bérénice (2011). "Ban Don Ta Phet and Khao Sam Kaeo: The Earliest Indian Contacts Re-assessed". In Manguin, Pierre-Yves; Mani, A.; Wade, Geoff (eds.). Early Interactions between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-Cultural Exchange. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute. pp. 17–46. ISBN 978-981-4311-17-5.

- ^ Li, Tana (2011). "Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ) in the Han period Tongking Gulf". In Cooke, Nola; Li, Tana; Anderson, James A. (eds.). The Tongking Gulf Through History. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 39–44. ISBN 978-0-8122-0502-2.

- ^ a b Chirikure, Shadreck (2022). "Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean World". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 149–176. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ Sen, Tansen (3 February 2014). "Maritime Southeast Asia Between South Asia and China to the Sixteenth Century". TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia. 2 (1): 31–59. doi:10.1017/trn.2013.15. S2CID 140665305.

- ^ Bopearachchi, Osmund (2022). "Indian Ocean Trade through Buddhist Iconographies". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 243–266. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ McGrail, Seán (2001). Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to the Medieval Times. Oxford University Press. pp. 289–293. ISBN 978-0-19-927186-3.

- ^ a b Herrera, Michael B.; Thomson, Vicki A.; Wadley, Jessica J.; Piper, Philip J.; Sulandari, Sri; Dharmayanthi, Anik Budhi; Kraitsek, Spiridoula; Gongora, Jaime; Austin, Jeremy J. (March 2017). "East African origins for Madagascan chickens as indicated by mitochondrial DNA". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (3) 160787. Bibcode:2017RSOS....460787H. doi:10.1098/rsos.160787. hdl:2440/104470. PMC 5383821. PMID 28405364.

- ^ Tofanelli, S.; Bertoncini, S.; Castri, L.; Luiselli, D.; Calafell, F.; Donati, G.; Paoli, G. (1 September 2009). "On the Origins and Admixture of Malagasy: New Evidence from High-Resolution Analyses of Paternal and Maternal Lineages". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (9): 2109–2124. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp120. PMID 19535740.

- ^ Adelaar, Alexander (June 2012). "Malagasy Phonological History and Bantu Influence". Oceanic Linguistics. 51 (1): 123–159. doi:10.1353/ol.2012.0003. hdl:11343/121829.

- ^ "Did You Know? Madagascar on the Maritime Silk Roads". Silk Roads Programme, UNESCO. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ Sulistiyono, Singgih Tri; Masruroh, Noor Naelil; Rochwulaningsih, Yety (2018). "Contest For Seascape: Local Thalassocracies and Sino-Indian Trade Expansion in the Maritime Southeast Asia During the Early Premodern Period". Journal of Marine and Island Cultures. 7 (2). doi:10.21463/jmic.2018.07.2.05.

- ^ Park, Hyunhee (2022). "Open Space and Flexible Borders: Theorizing Maritime Space through Premodern Sino-Islamic Connections". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 45–70. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ "Butuan Archeological Sites". UNESCO. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Clark, Paul; Green, Jeremy; Santiago, Rey; Vosmer, Tom (1993). "The Butuan Two boat known as a balangay in the National Museum, Manila, Philippines". The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 22 (2): 143–159. Bibcode:1993IJNAr..22..143C. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1993.tb00403.x.

- ^ a b Lacsina, Ligaya (2014). Re-examining the Butuan Boats: Pre-colonial Philippine watercraft. National Museum of the Philippines.

- ^ a b c d e f L. Pham, Charlotte Minh-Hà (2012). Asian Shipbuilding Technology. Bangkok: UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-92-9223-413-3. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d Heng, Derek (2019). "Ships, Shipwrecks, and Archaeological Recoveries as Sources of Southeast Asian History". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History: 1–29. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.97. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann (2016). "Śrīvijaya Revisited: Reflections on State Formation of a Southeast Asian Thalassocracy". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 102 (1): 45–95. doi:10.3406/befeo.2016.6231.

- ^ Munoz, Paul Michel (2006). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 981-4155-67-5.

- ^ "The Majapahit era". Britannica. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ Leyden, John (1821), Malay Annals (translated from the Malay language), Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown.

- ^ Tan Ta Sen & al. Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2009. ISBN 978-981-230-837-5.

- ^ a b Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1993). "The Vanishing Jong: Insular Southeast Asian Fleets in Trade and War (Fifteenth to Seventeenth Centuries)". In Reid, Anthony (ed.). Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era. Cornell University Press. pp. 197–213. ISBN 978-0-8014-8093-5. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctv2n7gng.15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kimura, Jun (2022). "Archaeological Evidence of Shipping and Shipbuilding Along The Maritime Silk Road". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 97–128. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ Lacsina, Ligaya (2016). "Boats of the Precolonial Philippines: Butuan Boats". Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. pp. 948–954. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7747-7_10279. ISBN 978-94-007-7746-0.

- ^ "Did You Know? The Butuan Archaeological Sites and the Role of the Philippines in the Maritime Silk Roads". UNESCO. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Clark, Paul; Green, Jeremy; Santiago, Rey; Vosmer, Tom (1993). "The Butuan Two boat known as a balangay in the National Museum, Manila, Philippines". The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 22 (2): 143–159. Bibcode:1993IJNAr..22..143C. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1993.tb00403.x.

- ^ Flecker, Michael (2002). The Archaeological Excavation of the 10th Century Intan Shipwreck. doi:10.30861/9781841714288. ISBN 978-1-84171-428-8.

- ^ Flecker, Michael (October 2001). "The Bakau wreck: an early example of Chinese shipping in Southeast Asia". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 30 (2): 221–230. Bibcode:2001IJNAr..30..221F. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2001.tb01369.x.

- ^ Coppola, Brian P. "The Turiang Shipwreck (ca. 1370)". College of Literature, Science, and the Arts. University of Michigan. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Miksic, John N. (2022). "Chinese Ceramics on the Maritime Silk Road". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 179–213. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ Heng, Derek (2022). "Urban Demographics along the Asian Maritime Silk Road". In Billé, Franck; Mehendale, Sanjyot; Lankton, James (eds.). The Maritime Silk Road: Global Connectivities, Regional Nodes, Localities (PDF). Asian Borderlands. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 215–241. ISBN 978-90-4855-242-9.

- ^ "UNESCO Expert Meeting for the World Heritage Nomination Process of the Maritime Silk Routes". UNESCO.

- ^ "The Trade Routes and the Diffusion of Artistic Traditions in South and Southeast Asia | Silk Roads Programme". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 2025-05-19.

- ^ Pillalamarri, Akhilesh. "How India Influenced Southeast Asian Civilization". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2025-05-19.

Maritime Silk Road

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Historiography

Conceptual Origins

The concept of the Maritime Silk Road originated as an extension of the historiographical framework established for the overland Silk Road, with German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen coining the term "Seidenstraße" (Silk Road) in 1877 to describe ancient Eurasian trade networks centered on silk exports from China.[3] Von Richthofen's five-volume China (1877–1912) emphasized land routes from China through Central Asia to the Mediterranean, but he documented maritime extensions via the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, noting their role in commodity flows like spices, ceramics, and precious metals as early as the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE).[4] These sea paths, however, were not unified under a single "road" in ancient records; instead, they comprised decentralized networks driven by monsoon winds and operated predominantly by Austronesian mariners from island Southeast Asia, who established connections to India and East Africa by the 2nd century BCE. Empirical evidence from shipwrecks, such as the 9th-century Belitung wreck carrying Tang dynasty ceramics, underscores the multi-ethnic character of this trade, challenging narratives that overstate Chinese initiative.[5] The explicit phrase "Maritime Silk Road" (Haishang Sichou zhi lu in Chinese) gained traction in mid-20th-century scholarship, particularly in post-1949 Chinese historiography, which reframed ancient sea routes to highlight cultural diffusion and economic outreach from China.[1] By the 1980s, amid UNESCO's Silk Roads Programme (initiated 1988), Western and Asian academics adopted the term to denote parallel oceanic conduits, drawing on archaeological finds like Sa Huỳnh culture artifacts (c. 1000 BCE–200 CE) evidencing early Austronesian-Indian Ocean links.[6] This conceptualization, while grounded in verifiable trade data—such as Roman glassware in Southeast Asian sites—has been critiqued for retrojecting a linear "road" model onto fragmented, opportunistic voyages influenced by local polities like Srivijaya (7th–13th centuries CE), rather than state-directed corridors.[7] Source biases in state-sponsored Chinese studies, which prioritize civilizational continuity, often underplay the agency of non-Chinese actors, as evidenced by genetic and linguistic traces of Austronesian expansion predating Han maritime records.[5] In the 21st century, the term's conceptual revival occurred with Chinese President Xi Jinping's proposal of the "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" on September 7, 2013, during a speech in Nazarbayev University, Kazakhstan, and reiterated October 3, 2013, in Indonesia, framing it as a geopolitical-economic initiative under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[8] This modern iteration builds on historical precedents but shifts emphasis toward infrastructure connectivity, with investments exceeding $1 trillion by 2023 in ports from Gwadar to Djibouti, though causal analysis reveals strategic naval projection motives alongside trade facilitation.[9] Academic caution persists regarding over-romanticization, as pre-modern routes declined post-15th century due to Ming withdrawal and European gunpowder dominance, not inherent transformation.[10]Evolution of the Term

The term "Maritime Silk Road" emerged as an extension of the overland "Silk Road" concept, which German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen introduced in 1877 as die Seidenstrasse to describe ancient trade networks linking Han China and the Roman Empire primarily by land.[1] In his multivolume China (published 1877–1912), Richthofen alluded to maritime dimensions by referencing routes in classical sources, such as the "Seidenstraße des Marinus" drawn from the geographer Marinus of Tyre (1st–2nd century CE), thereby laying early groundwork for conceptualizing sea-based extensions of silk and commodity exchanges across the Indian Ocean and South China Sea.[11] However, Richthofen's focus remained predominantly terrestrial, with maritime elements treated as supplementary due to limited contemporary evidence like the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea or Ptolemy's Geography.[1] Early 20th-century scholarship expanded this framework using newly translated Chinese annals and Greco-Roman texts; for instance, French Sinologist Paul Pelliot in 1904 and George Coedès in the 1930s reconstructed Southeast Asian entrepôts like Srivijaya as nodes in maritime diffusion of goods, Buddhism, and technologies, implicitly framing them within a silk-trade analogy without uniformly adopting the "maritime" label.[1] Post-World War II historians, including Dutch scholar J.C. van Leur, shifted emphasis from Eurocentric or Sinocentric narratives to indigenous Southeast Asian agency in "peddling trade" networks, critiquing unified "road" metaphors as oversimplifying polycentric exchanges but nonetheless popularizing maritime variants in works on Indian Ocean commerce from the 7th to 17th centuries.[1] The phrase gained traction in the late 20th century amid decolonization-era historiography and international initiatives; the UNESCO Silk Roads Programme, launched in 1988, integrated maritime routes into its purview, promoting the term in exhibitions and publications to highlight cultural exchanges predating European dominance.[5] By the 1990s, Chinese academics like Wang Gungwu and international volumes such as The Maritime Silk Route: 2000 Years of Trade on the South China Sea (1996) formalized it to denote evolving networks from Han-era coastal voyages (circa 2nd century BCE) to Song-Yuan expansions.[1] In contemporary usage, the term surged with Chinese President Xi Jinping's 2013 proposal of the "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, announced during a speech in Indonesia on October 3, 2013, reframing historical trade for modern infrastructure and economic partnerships across Asia, Africa, and Europe—though critics note this politicizes a scholarly construct originally detached from state-driven narratives.[1][5]Historical Development

Prehistoric Predecessors

The prehistoric foundations of the Maritime Silk Road trace back to the expansive seafaring networks of Austronesian peoples, who initiated long-distance maritime interactions across Southeast Asia and into the Indian Ocean during the Neolithic era. Originating from Taiwan around 3000 BCE, Austronesian speakers rapidly dispersed southward and eastward using advanced outrigger canoes and double-hulled vessels capable of open-sea voyages.[12] This expansion, spanning over 2,000 years, established interconnected island-hopping routes that facilitated the exchange of goods, technologies, and cultural elements long before formalized Silk Road trade. Archaeological evidence underscores these early networks, including the widespread distribution of Austronesian boat-building techniques such as lashed-lug construction and outriggers, which enabled voyages from the Philippines to eastern Indonesia by 2000 BCE.[13] Material exchanges, such as nephrite jade artifacts traded across the South China Sea and into mainland Southeast Asia from around 2500 BCE, demonstrate proto-trade systems that linked Taiwan, the Philippines, and Vietnam.[14] These jade routes, evidenced by sourced artifacts in burial sites, prefigured later commodity flows and highlight regional interdependencies predating bronze-age metallurgy.[1] By approximately 1500 BCE, Austronesian mariners extended their reach westward into the Indian Ocean, establishing contacts with southern India and Sri Lanka through exchanges of maritime technologies like catamarans and sewn-plank boats.[15] This phase introduced elements of Austronesian material culture, including double-outrigger canoes, to Indian coastal societies, fostering bidirectional trade in prestige goods and navigational knowledge. Further evidence from linguistic and genetic studies supports persistent Austronesian voyages across the Indian Ocean, reaching as far as Madagascar by integrating with local African populations around 500-1000 CE, though initial contacts were earlier.[15] These prehistoric pathways created a maritime continuum that later Silk Road participants would expand upon, emphasizing Southeast Asia's role as a nexus rather than a mere conduit.[16]Classical Era Foundations (2nd century BCE–3rd century CE)

The Maritime Silk Road's classical foundations emerged during the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE–9 CE), as imperial expansion into southern regions like Lingnan facilitated the development of coastal ports and initial overseas voyages. Archaeological excavations at Hepu in Guangxi province have uncovered Han-era tombs containing imported glass beads, carnelian, and etched stones typical of Indo-Pacific trade networks, dating from the 2nd century BCE onward, which attest to early maritime exchanges with Southeast Asian polities and possibly Indian intermediaries.[17] These finds coincide with textual records of Han administrative efforts to control southern sea routes, including the establishment of commanderies that supported shipping from ports like Hepu and Panyu (modern Guangzhou) to nearby coastal areas in present-day Vietnam and beyond.[18] Such activities built upon pre-existing Austronesian seafaring capabilities but marked China's proactive integration into regional maritime commerce, primarily for acquiring tribute goods like rhinoceros horn, ivory, and pearls in exchange for silk and iron tools. By the 1st century CE, these routes extended westward into the Indian Ocean, as evidenced by the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a Greco-Roman navigational guide composed around 40–70 CE, which details trade from Red Sea ports to Indian emporia like Barygaza and Muziris, and further to the "Golden Chersonese" (likely the Malay Peninsula).[19] The text references high-value silk fabrics arriving via northern hinterlands beyond Southeast Asian ports such as Kataigara (in the Red River Delta), implying indirect flows from Han China through intermediary kingdoms.[20] This connectivity expanded under Eastern Han (25–220 CE), with increased volume in commodities like Chinese lacquer and silk moving southward, swapped for spices, cotton textiles, and precious stones from India and Southeast Asia; Roman demand for silk, funneled through these sea lanes to bypass Parthian overland monopolies, further stimulated the network by the late 1st century BCE.[21] Direct evidence of end-to-end linkage appears in the Hou Hanshu (Book of the Later Han), recording the arrival of self-proclaimed Roman envoys in 166 CE at the port of Rinan via maritime passage from the "western sea," carrying tribute including ivory and rhinoceros horn—goods sourced along the route—demonstrating functional awareness and utilization of the chain from the Roman Empire to Han China.[22] Archaeological corroboration includes Indo-Pacific glass beads found in central Chinese sites like Nanyang, dated to the early 1st century CE, reflecting the influx of maritime-traded items into Han interiors.[23] These exchanges, though sporadic and mediated by multiple ethnic traders including Kushan and Southeast Asian groups, laid infrastructural precedents for later intensification, prioritizing bulk goods over luxury overland alternatives while exposing participants to navigational technologies like monsoon wind patterns.[24]Medieval Expansion (7th–14th centuries CE)

The Maritime Silk Road expanded markedly from the 7th to 14th centuries, driven by political consolidation in key regions, mastery of monsoon winds for seasonal voyages, and the integration of Islamic networks into preexisting Austronesian and Indian trade circuits. This era saw the rise of Srivijaya as a dominant thalassocracy in Southeast Asia, controlling the Strait of Malacca—a chokepoint for vessels linking the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean—by the late 7th century under King Balaputradewa, who fostered Buddhist diplomacy and tribute relations with Tang China.[25] Srivijaya's fleet enforced tolls on passing ships, amassing wealth from spices, aromatics, and forest products rerouted to Chinese and Indian markets, with Palembang serving as its primary entrepôt handling up to 1,000 ships annually at its peak around 800 CE.[26] Concurrent with Srivijaya's hegemony, Arab and Persian traders, empowered by the Abbasid Caliphate's stability after 750 CE, utilized lateen-rigged dhows to dominate western Indian Ocean routes, departing from Siraf and Basra to connect with East African ports like Kilwa and Indian centers such as Gujarat.[27] By the 9th century, these networks facilitated the export of 50,000-60,000 Tang dynasty ceramics in single cargoes, as evidenced by the Belitung shipwreck of circa 830 CE, where an Iraqi-built dhow—laden with Changsha bowls, star tiles, and ewers from Guangzhou—sank en route to the Persian Gulf, underscoring direct China-to-Arabia linkages bypassing multiple intermediaries.[28] This wreck, recovered with over 60,000 artifacts, highlights the era's scale, with Chinese export porcelain comprising 70% of the cargo value, exchanged for ivory, spices, and glassware.[29] Chinese participation intensified under the Tang (618–907 CE) and especially Song (960–1279 CE) dynasties, shifting from tributary missions to commercial fleets; by the 11th century, Quanzhou hosted 100-200 foreign ships yearly, exporting silk, copper cash, and ceramics while importing pepper and incense, with Song naval innovations like watertight compartments enabling deeper voyages into the Indian Ocean.[30] The Song state's issuance of 3 million strings of cash for maritime commerce annually stimulated this boom, displacing Indian and Arab intermediaries in Southeast Asian trades.[31] Disruptions, such as Chola raids on Srivijaya in 1025 CE and Mongol conquests, temporarily fragmented routes but ultimately integrated them under Yuan oversight by the 13th century, with Ilkhanid envoys documenting 14th-century voyages from Hangzhou to Hormuz carrying textiles worth thousands of dinars.[32] This expansion fostered economic interdependence, with annual spice shipments from Indonesia reaching 1,000 tons by the 13th century, valued at 10 times their weight in gold, while East African gold and ivory flowed eastward, sustaining caliphal treasuries and Chinese mints.[33] Archaeological finds, including Persian coins in Sumatra and Chinese ewer molds in Iraq, confirm bidirectional flows, though overreliance on monsoon predictability exposed traders to piracy and storms, limiting convoy sizes to 10-20 vessels per season.[34] By 1400 CE, these networks spanned 5,000 nautical miles, prefiguring global circuits but constrained by polities prioritizing tribute over free trade.[1]Factors of Decline and Transformation (15th century onward)

The Ming Dynasty's cessation of large-scale maritime expeditions after 1433 marked a pivotal internal factor in the Maritime Silk Road's decline, as the empire redirected resources toward continental defense and agricultural recovery following the costly voyages of Zheng He, which had involved fleets of up to 317 ships and over 27,000 personnel across seven missions from 1405 to 1433.[35] Bureaucratic opposition, rooted in Confucian priorities favoring inland stability over overseas engagement, led to the destruction of naval records and imposition of haijin policies restricting private seafaring, thereby diminishing Chinese dominance in Indian Ocean shipping and allowing regional powers like Malacca to fill voids in entrepôt functions.[36] This withdrawal exacerbated vulnerabilities in the network's eastern terminus, where porcelain and silk exports had previously sustained high-volume exchanges. Externally, the arrival of Portuguese fleets from 1498 onward, spearheaded by Vasco da Gama's voyage that year linking Europe directly to Calicut, introduced naval coercion that fragmented established Asian trading monopolies held by Arab, Gujarati, and Malay merchants.[37] Leveraging superior artillery and caravels optimized for ocean warfare, Portugal enforced the cartaz licensing system, taxing or seizing vessels without passes and capturing strategic chokepoints such as Malacca in 1511, which redirected spice flows from Sumatran producers toward Lisbon-controlled routes.[38] This militarized approach, contrasting the consensual diplomacy of prior networks, reduced the volume of intra-Asian trade by imposing tolls that inflated costs and provoked retaliatory alliances among Muslim traders, culminating in a 30-50% drop in Gujarati shipping through the Red Sea by the mid-16th century as per Portuguese customs records.[39] The network's transformation ensued as European powers supplanted indigenous carriers, with Dutch and English East India Companies assuming dominance by the 17th century through fortified enclaves and joint-stock financing that scaled commodity volumes beyond pre-1500 levels, integrating Asian staples like pepper and textiles into Atlantic circuits.[40] While core routes persisted—evidenced by continued ceramic exports from Jingdezhen kilns adapting to European demand—the causal shift toward gunboat diplomacy and mercantilist enclosures eroded the decentralized, multi-ethnic equilibrium, fostering dependencies that persisted into colonial partitions and modern containerized shipping paradigms.[41] Archaeological yields from sites like the 16th-century Swahili coast forts underscore this hybridity, blending Indo-Persian motifs with Iberian armaments in evolving port morphologies.[42]Geographical Extent and Routes

Core Maritime Pathways

The core maritime pathways of the Maritime Silk Road centered on the South China Sea route, which extended from coastal ports in southern China through Southeast Asia into the Indian Ocean, connecting East Asia with South Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, and East Africa. This primary corridor emerged prominently from the 2nd century BCE, with voyages departing from hubs like Guangzhou and Quanzhou in Guangdong and Fujian provinces, where Han Dynasty records document early shipments of silk and ceramics southward by 111 BCE following the conquest of northern Vietnam.[43] Ships followed coastal routes along Vietnam's shores, entering the Gulf of Thailand and proceeding to the Malay Peninsula, often utilizing the Strait of Malacca as a chokepoint after the 7th century CE under Srivijaya's dominance, which facilitated transshipment to the Andaman Sea.[44] Navigation relied on monsoon patterns: northeast winds from October to April propelled vessels southwestward from Southeast Asia across the Indian Ocean to India's Coromandel or Malabar coasts, such as Muziris, where Roman traders awaited goods by the 1st century CE as evidenced by the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Return voyages harnessed southwest monsoons from May to September, carrying spices and incense back eastward, with direct crossings from Sumatra's northern tip spanning up to 3,000 nautical miles in favorable conditions.[20] Western extensions linked Indian ports to Arabian entrepôts like Aden and Muscat, then via the Red Sea to Roman Egypt or the Persian Gulf to Mesopotamia, integrating with overland networks by the 1st century CE.[43] A secondary pathway, the East China Sea Silk Route, diverged northward from Chinese ports to Korea and Japan, active from the 1st century CE but primarily exchanging regional commodities like iron and horses rather than the luxury goods defining transoceanic trade. Alternative routes occasionally bypassed the Malacca Strait via portages across the Kra Isthmus in Thailand, reducing exposure to piracy but adding overland costs, as utilized in early Tang Dynasty expeditions around 670 CE.[45] These pathways evolved with technological advances, such as outrigger canoes giving way to larger dhows and junks capable of 100-ton cargoes by the 9th century, as demonstrated by the Belitung wreck's traversal from China to Indonesia.[44] Overall, the routes spanned approximately 7,000 kilometers from China to the Red Sea, with annual fleets numbering in the hundreds during peak medieval periods, underscoring their role in sustaining bidirectional flows of silk, porcelain, and spices amid variable wind regimes and geopolitical controls.[46]Principal Ports and Trade Hubs

The principal ports of the Maritime Silk Road functioned as vital entrepôts, aggregating commodities from inland regions and enabling transshipment across monsoon-driven routes in the South China Sea, Bay of Bengal, and Indian Ocean. These hubs, active primarily from the 7th to 15th centuries CE, supported bidirectional trade in silk, porcelain, spices, and precious metals, with archaeological finds like ceramics and shipwrecks confirming extensive connectivity.[47][24] In southern China, Guangzhou (ancient Panyu) emerged as the earliest major outlet during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), evolving into the primary export point for silk and ceramics by the Tang era (618–907 CE), when it hosted Arab, Persian, and Southeast Asian merchants.[48] Quanzhou, rising in prominence during the Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), surpassed Guangzhou as China's premier maritime hub under the Yuan (1271–1368 CE), linking to over 100 foreign ports including those in India, Iran, and East Africa; a 13th-century three-masted shipwreck in Quanzhou Bay, laden with spices and Southeast Asian goods, underscores its shipbuilding and warehousing capabilities.[47][47] Southeast Asian polities anchored intermediate trade, with the Srivijaya Empire—centered on Palembang in Sumatra—dominating from the late 7th to 13th centuries CE as a thalassocratic power controlling the Strait of Malacca, the chokepoint for China-India Ocean voyages; its ports amassed Indian Ocean spices and redistributed Chinese silks, fostering Buddhist networks evidenced by inscriptions and Chinese records of tributary missions.[49][50] Later, Malacca supplanted Srivijaya after 1400 CE, serving as a multicultural clearinghouse for Gujarati, Javanese, and Chinese traders until Portuguese intervention in 1511.[24] On the Indian subcontinent, Muziris in Kerala thrived from the 1st century BCE to 14th century CE as a premier spice port, handling pepper, pearls, and textiles exchanged for Roman gold and Chinese silk, as detailed in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c. 1st century CE) and corroborated by amphorae shards and Yavanas (Indo-Greeks) settlements unearthed at nearby Pattanam.[51][52] Complementary western Indian ports like Barygaza (Bharuch) facilitated cotton and ivory outflows to Arabian intermediaries.[51] Western termini included Persian Gulf sites such as Siraf, a 9th–10th century CE hub for dhow traffic carrying Chinese porcelain to Baghdad, with traveler accounts like those of Sulayman al-Tajir (851 CE) describing its role in aggregating eastern goods for overland caravan links.[44] Aden in Yemen, pivotal from the 10th century CE, monopolized Red Sea access, taxing shipments of African ivory and Indian cottons en route to the Mediterranean, as evidenced by Fatimid-era coins and ceramics in its strata.[51][53]| Port | Region | Peak Period | Key Commodities Handled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guangzhou | South China | Han–Tang (206 BCE–907 CE) | Silk, ceramics, tea exports[48] |

| Quanzhou | Southeast China | Song–Yuan (960–1368 CE) | Porcelain, spices, medicines[47] |

| Palembang (Srivijaya) | Sumatra | 7th–13th centuries CE | Spices redistribution, Buddhist relics[49] |

| Muziris | Kerala, India | 1st BCE–14th CE | Pepper, ivory, Roman imports[51] |

| Siraf | Persian Gulf | 9th–10th centuries CE | Porcelain to Mesopotamia[44] |

| Aden | Yemen | 10th–15th centuries CE | Ivory, cottons via Red Sea[51] |