Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

London dispersion force

View on Wikipedia

London dispersion forces (LDF, also known as dispersion forces, London forces, instantaneous dipole–induced dipole forces, fluctuating induced dipole bonds[1] or loosely as van der Waals forces) are a type of intermolecular force acting between atoms and molecules that are normally electrically symmetric; that is, the electrons are symmetrically distributed with respect to the nucleus.[2] They are part of the van der Waals forces. The LDF is named after the German physicist Fritz London. They are the weakest of the intermolecular forces.

Introduction

[edit]The electron distribution around an atom or molecule undergoes fluctuations in time. These fluctuations create instantaneous electric fields which are felt by other nearby atoms and molecules, which in turn adjust the spatial distribution of their own electrons. The net effect is that the fluctuations in electron positions in one atom induce a corresponding redistribution of electrons in other atoms, such that the electron motions become correlated. While the detailed theory requires a quantum-mechanical explanation (see quantum mechanical theory of dispersion forces), the effect is frequently described as the formation of instantaneous dipoles that (when separated by vacuum) attract each other. The magnitude of the London dispersion force is frequently described in terms of a single parameter called the Hamaker constant, typically symbolized . For atoms that are located closer together than the wavelength of light, the interaction is essentially instantaneous and is described in terms of a "non-retarded" Hamaker constant. For entities that are farther apart, the finite time required for the fluctuation at one atom to be felt at a second atom ("retardation") requires use of a "retarded" Hamaker constant.[3][4][5]

While the London dispersion force between individual atoms and molecules is quite weak and decreases quickly with separation like , in condensed matter (liquids and solids), the effect is cumulative over the volume of materials,[6] or within and between organic molecules, such that London dispersion forces can be quite strong in bulk solid and liquids and decay much more slowly with distance. For example, the total force per unit area between two bulk solids decreases by [7] where is the separation between them. The effects of London dispersion forces are most obvious in systems that are very non-polar (e.g., that lack ionic bonds), such as hydrocarbons and highly symmetric molecules like bromine (Br2, a liquid at room temperature) or iodine (I2, a solid at room temperature). In hydrocarbons and waxes, the dispersion forces are sufficient to cause condensation from the gas phase into the liquid or solid phase. Sublimation heats of e.g. hydrocarbon crystals reflect the dispersion interaction. Liquification of oxygen and nitrogen gases into liquid phases is also dominated by attractive London dispersion forces.

When atoms/molecules are separated by a third medium (rather than vacuum), the situation becomes more complex. In aqueous solutions, the effects of dispersion forces between atoms or molecules are frequently less pronounced due to competition with polarizable solvent molecules. That is, the instantaneous fluctuations in one atom or molecule are felt both by the solvent (water) and by other molecules.

Larger and heavier atoms and molecules exhibit stronger dispersion forces than smaller and lighter ones.[8] This is due to the increased polarizability of molecules with larger, more dispersed electron clouds. The polarizability is a measure of how easily electrons can be redistributed; a large polarizability implies that the electrons are more easily redistributed. This trend is exemplified by the halogens (from smallest to largest: F2, Cl2, Br2, I2). The same increase of dispersive attraction occurs within and between organic molecules in the order RF, RCl, RBr, RI (from smallest to largest) or with other more polarizable heteroatoms.[9] Fluorine and chlorine are gases at room temperature, bromine is a liquid, and iodine is a solid. The London forces are thought to arise from the motion of electrons.

Quantum mechanical theory

[edit]The first explanation of the attraction between noble gas atoms was given by Fritz London in 1930.[10][11][12] He used a quantum-mechanical theory based on second-order perturbation theory. The perturbation is because of the Coulomb interaction between the electrons and nuclei of the two moieties (atoms or molecules). The second-order perturbation expression of the interaction energy contains a sum over states. The states appearing in this sum are simple products of the stimulated electronic states of the monomers. Thus, no intermolecular antisymmetrization of the electronic states is included, and the Pauli exclusion principle is only partially satisfied.

London wrote a Taylor series expansion of the perturbation in , where is the distance between the nuclear centers of mass of the moieties.

This expansion is known as the multipole expansion because the terms in this series can be regarded as energies of two interacting multipoles, one on each monomer. Substitution of the multipole-expanded form of V into the second-order energy yields an expression that resembles an expression describing the interaction between instantaneous multipoles (see the qualitative description above). Additionally, an approximation, named after Albrecht Unsöld, must be introduced in order to obtain a description of London dispersion in terms of polarizability volumes, , and ionization energies, , (ancient term: ionization potentials).

In this manner, the following approximation is obtained for the dispersion interaction between two atoms and . Here and are the polarizability volumes of the respective atoms. The quantities and are the first ionization energies of the atoms, and is the intermolecular distance.

Note that this final London equation does not contain instantaneous dipoles (see molecular dipoles). The "explanation" of the dispersion force as the interaction between two such dipoles was invented after London arrived at the proper quantum mechanical theory. The authoritative work[13] contains a criticism of the instantaneous dipole model[14] and a modern and thorough exposition of the theory of intermolecular forces.

The London theory has much similarity to the quantum mechanical theory of light dispersion, which is why London coined the phrase "dispersion effect". In physics, the term "dispersion" describes the variation of a quantity with frequency, which is the fluctuation of the electrons in the case of the London dispersion.

Relative magnitude

[edit]Dispersion forces are usually dominant over the three van der Waals forces (orientation, induction, dispersion) between atoms and molecules, with the exception of molecules that are small and highly polar, such as water. The following contribution of the dispersion to the total intermolecular interaction energy has been given:[15]

| Molecule pair | % of the total energy of interaction |

|---|---|

| Ne-Ne | 100 |

| CH4-CH4 | 100 |

| HCl-HCl | 86 |

| HBr-HBr | 96 |

| HI-HI | 99 |

| CH3Cl-CH3Cl | 68 |

| NH3-NH3 | 57 |

| H2O-H2O | 24 |

| HCl-HI | 96 |

| H2O-CH4 | 87 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Callister, William (December 5, 2000). Fundamentals of Materials Science and Engineering: An Interactive e . Text. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 25. ISBN 0-471-39551-X.

- ^ Callister, William D. Jr.; Callister, William D. Jr. (2001). Fundamentals of materials science and engineering : an interactive etext. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-39551-X. OCLC 45162154.

- ^ Israelachvili, Jacob N. (2011), "Interactions of Biological Membranes and Structures", Intermolecular and Surface Forces, Elsevier, pp. 577–616, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-375182-9.10021-1, ISBN 978-0-12-375182-9

- ^ Gelardi, G.; Flatt, R.J. (2016), "Working mechanisms of water reducers and superplasticizers", Science and Technology of Concrete Admixtures, Elsevier, pp. 257–278, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-100693-1.00011-4, ISBN 978-0-08-100693-1

- ^ LIFSHITZ, E.M.; Hamermesh, M. (1992), "The theory of molecular attractive forces between solids", Perspectives in Theoretical Physics, Elsevier, pp. 329–349, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-036364-6.50031-4, ISBN 9780080363646, retrieved 2022-08-29

- ^ Wagner, J.P.; Schreiner, P.R. (2015), "London dispersion in molecular chemistry — reconsidering steric effects", Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 54 (42), Wiley: 12274–12296, doi:10.1002/anie.201503476, PMID 26262562

- ^ Karlström, Gunnar; Jönsson, Bo (6 February 2013). "Intermolecular interactions" (PDF). Theoretical chemistry – Lund University. p. 45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "London Dispersion Forces". Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Schneider,Hans-Jörg Dispersive Interactions in Solution Complexes Dispersive Interactions in Solution Complexes Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48 , 1815–1822.[1]

- ^ R. Eisenschitz & F. London (1930), "Über das Verhältnis der van der Waalsschen Kräfte zu den homöopolaren Bindungskräften", Zeitschrift für Physik, 60 (7–8): 491–527, Bibcode:1930ZPhy...60..491E, doi:10.1007/BF01341258, S2CID 125644826

- ^ London, F. (1930), "Zur Theorie und Systematik der Molekularkräfte", Zeitschrift für Physik, 63 (3–4): 245, Bibcode:1930ZPhy...63..245L, doi:10.1007/BF01421741, S2CID 123122363. English translations in H. Hettema, ed. (2000), Quantum Chemistry, Classic Scientific Papers, Singapore: World Scientific, ISBN 981-02-2771-X, OCLC 898989103, OL 9194584M which is reviewed in Parr, Robert G. (2001), "Quantum Chemistry: Classic Scientific Papers", Physics Today, 54 (6): 63–64, Bibcode:2001PhT....54f..63H, doi:10.1063/1.1387598

- ^ F. London (1937), "The general theory of molecular forces", Transactions of the Faraday Society, 33: 8–26, doi:10.1039/tf937330008b

- ^ J. O. Hirschfelder; C. F. Curtiss & R. B. Bird (1954), Molecular Theory of Gases and Liquids, New York: Wiley

- ^ A. J. Stone (1996), The Theory of Intermolecular Forces, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- ^ Jacob Israelachvili (1992), Intermolecular and Surface Forces (2nd ed.), Academic Press

London dispersion force

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

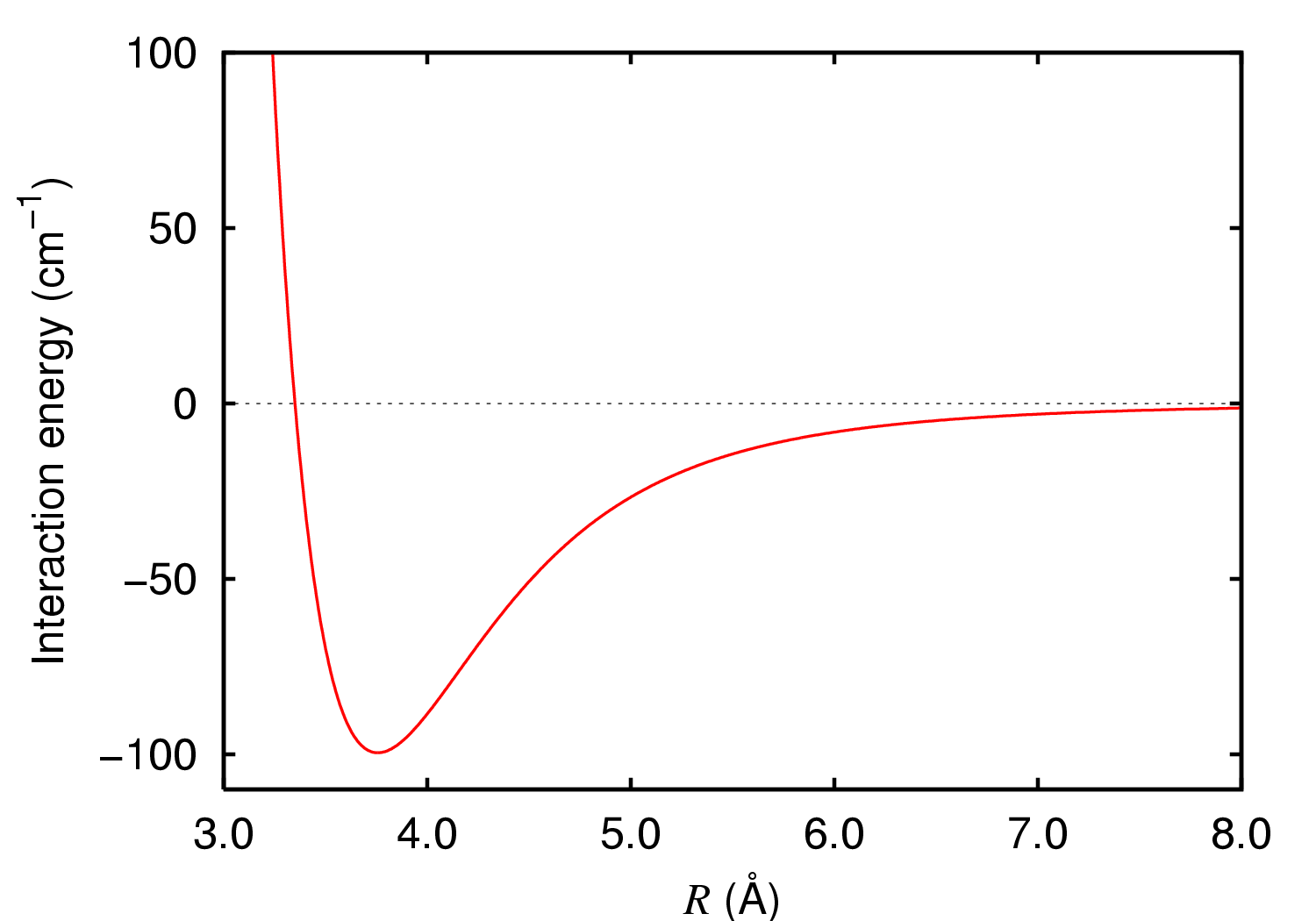

London dispersion forces are a type of van der Waals force arising from temporary fluctuations in the electron distribution of atoms or molecules, which create instantaneous dipoles that induce corresponding dipoles in neighboring particles, resulting in an attractive interaction between them.[1] These forces originate from transient correlated momentary dipoles and are fundamentally quantum mechanical in nature.[2] A key characteristic of London dispersion forces is their universal presence in all atoms and molecules, irrespective of whether the particles are polar or nonpolar.[3] They are always attractive and isotropic, meaning they act equally in all directions without dependence on molecular orientation.[4] For pairwise interactions, the strength of these forces decreases rapidly with distance, following an inverse sixth-power dependence (1/R⁶).[5] Within the broader category of van der Waals forces, London dispersion represents the universal component that applies to every particle containing electrons, in contrast to more specific interactions like permanent dipole-dipole forces or hydrogen bonding, which require fixed charge separations.[6] These dispersion forces enable cohesion in nonpolar substances by providing the weak but essential attractions that allow them to condense into liquids or solids, such as the liquefaction of noble gases like helium or argon under sufficiently low temperatures and high pressures.[7]Historical Development

In the late 19th century, Johannes Diderik van der Waals recognized the existence of attractive forces between molecules in non-polar gases, which deviated from ideal gas behavior, as incorporated into his 1873 equation of state that accounted for molecular volume and intermolecular attractions through the parameter 'a'.[8] These forces, later understood as a component of van der Waals forces, explained phenomena such as gas liquefaction and compressibility in real gases.[8] Prior to a quantum mechanical interpretation, Peter Debye contributed in 1920 by developing the theory of dipole-induced dipole interactions, emphasizing the role of molecular polarizability in generating attractive forces between a permanent dipole and an inducible one, though without addressing quantum fluctuations in non-polar systems.[9] Debye's work laid groundwork for understanding induction effects but did not fully explain attractions in non-polar molecules like noble gases.[10] The quantum-based explanation for these dispersion interactions emerged in 1930 through Fritz London's seminal paper, where he derived the attractive potential arising from correlated electron fluctuations and instantaneous dipoles in non-polar atoms and molecules, providing a rigorous theoretical foundation using second-order perturbation theory. London's formulation unified the treatment of intermolecular forces, highlighting their universal presence even in systems lacking permanent dipoles.[11] In the 1930s and 1940s, London's ideas were refined and integrated into broader theories of intermolecular potentials, including the 1930 derivation of the dispersion interaction by Eisenschitz and London.[5] Further developments by various researchers extended these models to applications in condensed phases.[12] The forces became commonly known as London dispersion forces in recognition of Fritz London's foundational quantum explanation, solidifying their role in chemical physics.[12]Theoretical Basis

Classical Instantaneous Dipole Model

The classical instantaneous dipole model describes London dispersion forces as arising from temporary fluctuations in electron distribution within neutral atoms or molecules, leading to attractive interactions without invoking quantum mechanics. In this simplified picture, electrons in a molecule are in constant motion due to thermal energy, occasionally resulting in an uneven charge distribution that creates a transient dipole moment, with one side momentarily more negative and the other more positive.[3] This instantaneous dipole generates an electric field that influences nearby molecules.[13] The mechanism proceeds in three key steps: first, the random movement of electrons in one molecule produces the initial transient dipole; second, the electric field from this dipole polarizes a neighboring molecule by distorting its electron cloud, inducing an oppositely oriented dipole; and third, the positive end of the induced dipole is attracted to the negative end of the original dipole (and vice versa), yielding a net attractive force between the molecules.[3] This process occurs dynamically, with dipoles forming and dissipating rapidly, but their average effect over time results in a weak, cumulative attraction.[13] To illustrate qualitatively, consider two adjacent helium atoms, each with a symmetric electron cloud under normal conditions. If electrons in one atom momentarily cluster on the side away from the other, it forms a dipole; this asymmetry repels electrons in the second atom toward its far side, creating an aligned induced dipole. The resulting configuration resembles two bar magnets attracting end-to-end, though the effect is fleeting and probabilistic.[13] Such thought experiments highlight the model's reliance on classical electrostatics, treating electrons as point charges in orbital motion without wave-like properties. This classical framework qualitatively explains the cohesion observed in nonpolar substances like noble gases at low temperatures, where dispersion forces provide the only significant intermolecular attraction, enabling liquefaction of helium or argon despite their lack of permanent dipoles.[14] For instance, the model accounts for why argon molecules aggregate into liquids below 87 K, as transient dipoles foster weak but sufficient binding to overcome thermal disruption.[13] However, the model has notable limitations, as it assumes classical electron behavior and cannot explain the fundamental origin of the electron fluctuations, which stem from quantum mechanical correlations rather than purely random motion.[15] It also fails to predict precise interaction strengths or distances, treating the process as a static induction rather than a correlated, time-averaged quantum effect, thus serving primarily as an intuitive precursor to more rigorous derivations.[16]Quantum Mechanical Derivation

The quantum mechanical foundation of London dispersion forces was established by Fritz London in 1930 through the application of second-order Rayleigh-Schrödinger perturbation theory to the interaction between two neutral atoms.[17] Consider two atoms A and B, each described by their unperturbed Hamiltonians and , with the total Hamiltonian given by , where is the perturbative interaction potential arising from the Coulomb interactions between electrons and nuclei of the two atoms.[17] The interaction is expanded in a multipole series, with the leading dipole-dipole term scaling as , where is the intermolecular distance.[18] In second-order perturbation theory, the correction to the ground-state energy is where is the unperturbed ground state (product of ground states of A and B), and are the excited states of the combined system. For dispersion forces, the relevant contributions arise from terms where both atoms are virtually excited simultaneously (double excitations), excluding charge-transfer or induction effects. Applying this to the dipole-dipole interaction yields the dispersion energy as where is the dipole-dipole operator, and the sums run over excited states of A and of B. To obtain a closed-form expression, London employed the Unsöld approximation (or closure approximation), replacing the excitation energies with an average value related to the ionization energies and , and expressing the matrix elements in terms of static dipole polarizabilities and .[17] This leads to the seminal London formula for the leading-order dispersion energy at large separations: where quantifies the ease of inducing a dipole moment (in units of volume, e.g., ų), approximates the characteristic excitation energy (in energy units, e.g., eV), and the dependence emerges from the second-order treatment of the dipole-dipole potential.[17] This approximation captures the attractive nature of the force while highlighting its quantum origin in correlated electron fluctuations.[17] At very long distances, where retardation effects due to the finite speed of light become significant, the form transitions to , as described by the Casimir-Polder formula, which incorporates frequency-dependent polarizabilities integrated over imaginary frequencies. In modern computational chemistry, density functional theory (DFT) methods, augmented with dispersion corrections like DFT-D3, routinely compute these energies by evaluating the perturbation sum or its approximations directly from electron densities, enabling accurate predictions for complex systems.Magnitude and Factors

Factors Influencing Strength

The strength of London dispersion forces depends significantly on molecular size and polarizability. Larger atoms and molecules possess more electrons and larger electron clouds, which are more easily distorted to form temporary dipoles, resulting in stronger attractive interactions.[3] For instance, the boiling points of the diatomic halogens rise progressively down the group—from −188 °C for F₂ to 184 °C for I₂—owing to the increasing atomic size and polarizability that amplify dispersion forces.[19] Polarizability (α) scales approximately with molecular volume, as greater volume facilitates larger fluctuations in electron distribution and thus more pronounced induced dipoles.[20] Molecular shape further modulates the interaction strength by influencing the effective contact area between molecules. Elongated or linear molecules enable closer and more extensive overlap of electron clouds compared to branched or spherical ones, leading to enhanced dispersion forces.[21] A clear example is provided by the isomers n-pentane and neopentane, both C₅H₁₂: n-pentane has a boiling point of 36 °C due to its linear structure allowing greater surface interaction, while the more compact neopentane boils at 9.5 °C.[3] Temperature affects the manifestation of dispersion forces, as higher thermal energy increases molecular kinetic motion, which disrupts the transient alignment of dipoles and reduces the net attractive effect.[22] Consequently, nonpolar substances remain gaseous at elevated temperatures but condense into liquids or solids upon cooling, when thermal disruption is minimized and dispersion forces can dominate cohesion.[3] The distance between interacting entities governs the force magnitude, with pairwise interactions decaying as , where is the intermolecular separation—a dependence originating from quantum mechanical treatments of correlated electron fluctuations.[3] In macroscopic contexts, such as bulk materials or colloidal suspensions, this is aggregated into the Hamaker constant , a material-specific parameter quantifying the overall dispersion attraction; for organic substances, typically falls in the range of $4 to $7 \times 10^{-20} J.[23] Surrounding environmental conditions also influence dispersion strength. In vacuum, forces operate at full intensity without interference, but in solvents, they are attenuated by dielectric screening from the medium and competing interactions with solvent molecules.[24] For colloidal systems, dispersion contributes to interparticle attractions at surfaces, promoting aggregation as described in DLVO theory, where the Hamaker constant captures the effective van der Waals component across the medium.[25]Relative Importance in Intermolecular Forces

London dispersion forces represent the weakest category of intermolecular forces, with typical interaction energies ranging from 0.05 to 40 kJ/mol, though they are ubiquitous and present between all molecular pairs regardless of polarity.[26] In contrast, dipole-dipole interactions typically span 5 to 25 kJ/mol, hydrogen bonding ranges from 10 to 40 kJ/mol, and ionic interactions are substantially stronger, often exceeding 100 kJ/mol for ion-dipole or ion-ion contacts.[26][27] This hierarchy positions dispersion forces as generally subordinate in systems where stronger interactions dominate, yet their universality ensures they contribute to cohesion in every molecular aggregate.[21] Dispersion forces dominate entirely (100%) in interactions between non-polar molecules, such as noble gases or hydrocarbons like methane (CH₄), where no permanent dipoles exist to enable dipole-dipole or hydrogen bonding.[27] In polar systems, their role is partial, where hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole forces predominate but dispersion still modulates the total attraction.| Molecular Pair | Dispersion Contribution (%) | Qualitative Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| CH₄-CH₄ | 100 | Non-polar symmetric molecules; no dipole-dipole or hydrogen bonding possible, so dispersion is the sole attractive force.[27] |

Examples and Applications

Molecular and Chemical Examples

London dispersion forces are particularly evident in non-polar molecules, where they serve as the primary intermolecular interaction responsible for physical properties such as boiling points. In the halogen series, the boiling points increase significantly from fluorine gas (F₂, –188.1°C) to iodine (I₂, 184.3°C), a trend attributed to the increasing molecular size and polarizability, which enhance the strength of dispersion forces.[28] Similarly, among the noble gases, boiling points rise from helium (–268.6°C) to xenon (–107.1°C) due to larger atomic radii allowing for greater electron cloud distortion and thus stronger temporary dipole attractions.[28] These examples highlight how dispersion forces scale with molecular or atomic size in systems lacking permanent dipoles.| Noble Gas | Boiling Point (°C) | Halogen | Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| He | –268.6 | F₂ | –188.1 |

| Ne | –245.9 | Cl₂ | –34.6 |

| Ar | –185.7 | Br₂ | 58.8 |

| Kr | –152.3 | I₂ | 184.3 |

| Xe | –107.1 |