Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Oxford English Dictionary

View on Wikipedia

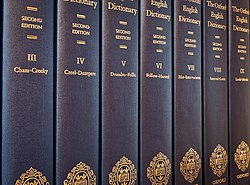

Seven of the twenty volumes of the printed second edition of The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Oxford University Press |

| Published |

|

| Website | oed |

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP), a University of Oxford publishing house. The dictionary, which began publication in 1884, traces the historical development of the English language, providing a comprehensive resource to scholars and academic researchers, and provides ongoing descriptions of English language usage in its variations around the world.[2]

Work began on the dictionary in 1857, although publication did not commence until 1884. The work then began to be issued incrementally in unbound fascicles (instalments), as work continued on other parts of the project. The original title was A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society. In 1895, the title The Oxford English Dictionary was first used unofficially on the covers of the series, and in 1928 the full dictionary was republished in 10 bound volumes.

In 1933, the title The Oxford English Dictionary fully replaced the former name in all occurrences in its reprinting as 12 volumes with a one-volume supplement. More supplements came over the years until 1989, when the second edition was published, comprising 21,728 pages in 20 volumes.[1] Since 2000, compilation of a third edition of the dictionary has been underway, approximately half of which was complete by 2018.[1]

In 1988, the first electronic version of the dictionary was made available, and the online version has been available since 2000. By April 2014, it was receiving over two million visits per month. The third edition of the dictionary is expected to be available exclusively in electronic form; the CEO of OUP has stated that it is unlikely that it will ever be printed.[1][3][4]

Historical nature

[edit]As a historical dictionary, the Oxford English Dictionary features entries in which the earliest ascertainable recorded sense of a word, whether current or obsolete, is presented first, and each additional sense is presented in historical order according to the date of its earliest ascertainable recorded use.[5] Following each definition are several brief illustrating quotations presented in chronological order from the earliest ascertainable use of the word in that sense to the last ascertainable use for an obsolete sense, to indicate both its life span and the time since its desuetude, or to a relatively recent use for current ones.

The format of the OED's entries has influenced numerous other historical lexicography projects. The forerunners to the OED, such as the early volumes of the Deutsches Wörterbuch, had initially provided few quotations from a limited number of sources, whereas the OED editors preferred larger groups of quite short quotations from a wide selection of authors and publications. This influenced later volumes of this and other lexicographical works.[6]

Entries and relative size

[edit]

According to the publishers, it would take a single person 120 years to "key in" the 59 million words of the OED second edition, 60 years to proofread them, and 540 megabytes to store them electronically.[7] As of 30 November 2005, the Oxford English Dictionary contained approximately 301,100 main entries. Supplementing the entry headwords, there are 157,000 bold-type combinations and derivatives;[8] 169,000 italicized-bold phrases and combinations;[9] 616,500 word-forms in total, including 137,000 pronunciations; 249,300 etymologies; 577,000 cross-references; and 2,412,400 usage quotations. The dictionary's latest, complete print edition (second edition, 1989) was printed in 20 volumes, comprising 291,500 entries in 21,730 pages. The longest entry in the OED2 was for the verb set, which required 60,000 words to describe some 580 senses (430 for the bare verb, the rest in phrasal verbs and idioms). As entries began to be revised for the OED3 in sequence starting from M, the record was progressively broken by the verbs make in 2000, then put in 2007, then run in 2011 with 645 senses.[10][11][12]

Despite its considerable size, the OED is neither the world's largest nor the earliest exhaustive dictionary of a language. Another earlier large dictionary is the Grimm brothers' dictionary of the German language, begun in 1838 and completed in 1961. The first edition of the Vocabolario degli Accademici della Crusca is the first great dictionary devoted to a modern European language (Italian) and was published in 1612; the first edition of Dictionnaire de l'Académie française dates from 1694. The official dictionary of Spanish is the Diccionario de la lengua española (produced, edited, and published by the Royal Spanish Academy), and its first edition was published in 1780. The Kangxi Dictionary of Chinese was published in 1716.[13] The largest dictionary by number of pages is believed to be the Dutch Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal.[14][15]

History

[edit]| Oxford English Dictionary Publications | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication date |

Volume range |

Title | Volume |

| 1888 | A and B | A New ED | Vol. 1 |

| 1893 | C | NED | Vol. 2 |

| 1897 | D and E | NED | Vol. 3 |

| 1900 | F and G | NED | Vol. 4 |

| 1901 | H to K | NED | Vol. 5 |

| 1908 | L to N | NED | Vol. 6 |

| 1909 | O and P | NED | Vol. 7 |

| 1914 | Q to Sh | NED | Vol. 8 |

| 1919 | Si to St | NED | Vol. 9/1 |

| 1919 | Su to Th | NED | Vol. 9/2 |

| 1926 | Ti to U | NED | Vol. 10/1 |

| 1928 | V to Z | NED | Vol. 10/2 |

| 1928 | All | NED | 10 vols. |

| 1933 | All | NED | Suppl. |

| 1933 | All | Oxford ED | 13 vols. |

| 1972 | A to G | OED Sup. | Vol. 1 |

| 1976 | H to N | OED Sup. | Vol. 2 |

| 1982 | O to Sa | OED Sup. | Vol. 3 |

| 1986 | Se to Z | OED Sup. | Vol. 4 |

| 1989 | All | OED 2nd Ed. | 20 vols. |

| 1993 | All | OED Add. Ser. | Vols. 1–2 |

| 1997 | All | OED Add. Ser. | Vol. 3 |

Origins

[edit]The dictionary began as a Philological Society project of a small group of intellectuals in London (and unconnected to Oxford University):[16]: 103–104, 112 Richard Chenevix Trench, Herbert Coleridge, and Frederick Furnivall, who were dissatisfied with the existing English dictionaries. The society expressed interest in compiling a new dictionary as early as 1844,[17] but it was not until June 1857 that they began by forming an "Unregistered Words Committee" to search for words that were unlisted or poorly defined in current dictionaries. In November, Trench's report was not a list of unregistered words; instead, it was the study On Some Deficiencies in our English Dictionaries, which identified seven distinct shortcomings in contemporary dictionaries:[18]

- Incomplete coverage of obsolete words

- Inconsistent coverage of families of related words

- Incorrect dates for earliest use of words

- History of obsolete senses of words often omitted

- Inadequate distinction among synonyms

- Insufficient use of good illustrative quotations

- Space wasted on inappropriate or redundant content.

The society ultimately realized that the number of unlisted words would be far more than the number of words in the English dictionaries of the 19th century, and shifted their idea from covering only words that were not already in English dictionaries to a larger project. Trench suggested that a new, truly comprehensive dictionary was needed. On 7 January 1858, the society formally adopted the idea of a comprehensive new dictionary.[16]: 107–108 Volunteer readers would be assigned particular books, copying passages illustrating word usage onto quotation slips. Later the same year, the society agreed to the project in principle, with the title A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (NED).[19]: ix–x

Early editors

[edit]Richard Chenevix Trench (1807–1886) played the key role in the project's first months, but his appointment as Dean of Westminster meant that he could not give the dictionary project the time that it required. He withdrew and Herbert Coleridge became the first editor.[20]: 8–9

On 12 May 1860, Coleridge's dictionary plan was published and research was started. His house was the first editorial office. He arrayed 100,000 quotation slips in a 54 pigeon-hole grid.[20]: 9 In April 1861, the group published the first sample pages; later that month, Coleridge died of tuberculosis, aged 30.[19]: x

Thereupon Furnivall became editor; he was enthusiastic and knowledgeable, but temperamentally ill-suited for the work.[16]: 110 Many volunteer readers eventually lost interest in the project, as Furnivall failed to keep them motivated. Furthermore, many of the slips were misplaced.

Furnivall believed that, since many printed texts from earlier centuries were not readily available, it would be impossible for volunteers to efficiently locate the quotations that the dictionary needed. As a result, he founded the Early English Text Society in 1864 and the Chaucer Society in 1868 to publish old manuscripts.[19]: xii Furnivall's preparatory efforts lasted 21 years and provided numerous texts for the use and enjoyment of the general public, as well as crucial sources for lexicographers, but they did not actually involve compiling a dictionary. Furnivall recruited more than 800 volunteers to read these texts and record quotations. While enthusiastic, the volunteers were not well trained and often made inconsistent and arbitrary selections. Ultimately, Furnivall handed over nearly two tons of quotation slips and other materials to his successor.[21]

In the 1870s, Furnivall unsuccessfully attempted to recruit both Henry Sweet and Henry Nicol to succeed him. He then approached James Murray, who accepted the post of editor. In the late 1870s, Furnivall and Murray met with several publishers about publishing the dictionary. In 1878, Oxford University Press agreed with Murray to proceed with the massive project; the agreement was formalized the following year.[16]: 111–112 20 years after its conception, the dictionary project finally had a publisher. It would take another 50 years to complete.

Late in his editorship, Murray learned that one especially prolific reader, W. C. Minor, was confined to a mental hospital for (in modern terminology) schizophrenia.[16]: xiii Minor was a Yale University–trained surgeon and a military officer in the American Civil War who had been confined to Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane after killing a man in London. He invented his own quotation-tracking system, allowing him to submit slips on specific words in response to editors' requests. The story of how Murray and Minor worked together to advance the OED was retold in the 1998 book The Surgeon of Crowthorne (US title: The Professor and the Madman[16]), which was the basis for a 2019 film, The Professor and the Madman, starring Mel Gibson and Sean Penn.

Oxford editors

[edit]

During the 1870s, the Philological Society was concerned with the process of publishing a dictionary with such an immense scope.[1] They had pages printed by publishers, but no publication agreement was reached; both the Cambridge University Press and the Oxford University Press were approached. The OUP finally agreed in 1879 (after two years of negotiating by Sweet, Furnivall, and Murray) to publish the dictionary and to pay Murray, who was both the editor and the Philological Society president. The dictionary was to be published as interval fascicles, with the final form in four volumes, totalling 6,400 pages. They hoped to finish the project in ten years.[20]: 1

Murray started the project, working in a corrugated iron outbuilding called the "Scriptorium" which was lined with wooden planks, bookshelves, and 1,029 pigeon-holes for the quotation slips.[19]: xiii He tracked and regathered Furnivall's collection of quotation slips, which were found to concentrate on rare, interesting words rather than common usages. For instance, there were ten times as many quotations for abusion as for abuse.[22] He appealed, through newspapers distributed to bookshops and libraries, for readers who would report "as many quotations as you can for ordinary words" and for words that were "rare, obsolete, old-fashioned, new, peculiar or used in a peculiar way".[22] Murray had American philologist and liberal arts college professor Francis March manage the collection in North America; 1,000 quotation slips arrived daily to the Scriptorium and, by 1880, there were 2,500,000.[20]: 15

The first dictionary fascicle was published on 1 February 1884—twenty-three years after Coleridge's sample pages. The full title was A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society; the 352-page volume, words from A to Ant, cost 12s 6d[20]: 251 (equivalent to $82 in 2023). The total sales were only 4,000 copies.[23]: 169

The OUP saw that it would take too long to complete the work unless editorial arrangements were revised. Accordingly, new assistants were hired, and two new demands were made on Murray.[20]: 32–33 The first was that he move from Mill Hill to Oxford to work full-time on the project, which he did in 1885. Murray had his Scriptorium re-erected in the back garden of his new property.[19]: xvii

Murray resisted the second demand: that if he could not meet the schedule, he must hire a second, senior editor to work in parallel to him, outside his supervision, on words from elsewhere in the alphabet. Murray did not want to share the work, feeling that he would accelerate his work pace with experience. That turned out not to be so, and Philip Gell of the OUP forced the promotion of Murray's assistant Henry Bradley (hired by Murray in 1884), who worked independently in the British Museum in London beginning in 1888. In 1896, Bradley moved to Oxford University.[20]

Gell continued harassing Murray and Bradley with his business concerns – containing costs and speeding production – to the point where the project's collapse seemed likely. Newspapers reported the harassment, particularly the Saturday Review, and public opinion backed the editors.[23]: 182–83 Gell was fired, and the university reversed his cost policies. If the editors felt that the dictionary would have to grow larger, it would; it was an important work, and worth the time and money to finish properly.

Further progress

[edit]Neither Murray nor Bradley lived to see it. Murray died in 1915, having been responsible for words starting with A–D, H–K, O–P, and T, nearly half the finished dictionary; Bradley died in 1923, having completed E–G, L–M, S–Sh, St, and W–We. By then, two additional editors had been promoted from assistant work to independent work, continuing without much trouble. William Craigie started in 1901 and was responsible for N, Q–R, Si–Sq, U–V, and Wo–Wy.[19]: xix The OUP had previously thought London too far from Oxford but, after 1925, Craigie worked on the dictionary in Chicago, where he was a professor.[19]: xix [20] The fourth editor was Charles Talbut Onions, who compiled the remaining ranges starting in 1914: Su–Sz, Wh–Wo, and X–Z.[24]

In 1919–1920, J. R. R. Tolkien was employed by the OED, researching etymologies of the Waggle to Warlock range;[25] later he parodied the principal editors as "The Four Wise Clerks of Oxenford" in the story Farmer Giles of Ham.[26]

By early 1894, a total of 11 fascicles had been published, or about one per year: four for A–B, five for C, and two for E.[19] Of these, eight were 352 pages long, while the last one in each group was shorter to end at the letter break (which eventually became a volume break). At this point, it was decided to publish the work in smaller and more frequent instalments: once every three months beginning in 1895 there would be a fascicle of 64 pages, priced at 2s 6d. If enough material was ready, 128 or even 192 pages would be published together. This pace was maintained until World War I forced reductions in staff.[19]: xx Each time enough consecutive pages were available, the same material was also published in the original larger fascicles.[19]: xx Also in 1895, the title Oxford English Dictionary was first used. It then appeared only on the outer covers of the fascicles; the original title was still the official one and was used everywhere else.[19]: xx

Completion of first edition and first supplement

[edit]The 125th and last fascicle covered words from Wise to the end of W and was published on 19 April 1928, and the full dictionary in bound volumes followed immediately.[19]: xx William Shakespeare is the most-quoted writer in the completed dictionary, with Hamlet his most-quoted work. George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) is the most-quoted female writer. Collectively, the Bible is the most-quoted work (in many translations); the most-quoted single work is Cursor Mundi.[7]

Additional material for a given letter range continued to be gathered after the corresponding fascicle was printed, with a view towards inclusion in a supplement or revised edition. A one-volume supplement of such material was published in 1933, with entries weighted towards the start of the alphabet where the fascicles were decades old.[19] The supplement included at least one word (bondmaid) accidentally omitted when its slips were misplaced;[27] many words and senses newly coined (famously appendicitis, coined in 1886 and missing from the 1885 fascicle, which came to prominence when Edward VII's 1902 appendicitis postponed his coronation[28]); and some previously excluded as too obscure (notoriously radium, omitted in 1903, months before its discoverers Pierre and Marie Curie won the Nobel Prize in Physics[29]). Also in 1933 the original fascicles of the entire dictionary were re-issued, bound into 12 volumes, under the title "The Oxford English Dictionary".[30] This edition of 13 volumes including the supplement was subsequently reprinted in 1961 and 1970.

Second supplement

[edit]In 1933, Oxford had finally put the dictionary to rest; all work ended, and the quotation slips went into storage. However, the English language continued to change and, by 20 years later, the dictionary was outdated.[31]

There were three possible ways to update it. The cheapest would have been to leave the existing work alone and simply compile a new supplement of perhaps one or two volumes, but then anyone looking for a word or sense and unsure of its age would have to look in three different places. The most convenient choice for the user would have been for the entire dictionary to be re-edited and retypeset, with each change included in its proper alphabetical place; but this would have been the most expensive option, with perhaps 15 volumes required to be produced. The OUP chose a middle approach: combining the new material with the existing supplement to form a larger replacement supplement.

Robert Burchfield was hired in 1957 to edit the second supplement;[32] Charles Talbut Onions turned 84 that year but was still able to make some contributions as well. The work on the supplement was expected to take about seven years.[31] It actually took 29 years, by which time the new supplement (OEDS) had grown to four volumes, starting with A, H, O, and Sea. They were published in 1972, 1976, 1982, and 1986 respectively, bringing the complete dictionary to 16 volumes, or 17 counting the first supplement.

Burchfield emphasized the inclusion of modern-day language and, through the supplement, the dictionary was expanded to include a wealth of new words from the burgeoning fields of science and technology, as well as popular culture and colloquial speech. Burchfield said that he broadened the scope to include developments of the language in English-speaking regions beyond the United Kingdom, including North America, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, India, Pakistan, and the Caribbean. Burchfield also removed, for unknown reasons, many entries that had been added to the 1933 supplement.[33] In 2012, an analysis by lexicographer Sarah Ogilvie revealed that many of these entries were foreign loan words, despite Burchfield's claim that he included more such words. The proportion was estimated from a sample calculation to amount to 17% of the foreign loan words and words from regional forms of English. Some of these had only a single recorded usage, but many had multiple recorded citations, and it ran against what was thought to be the established OED editorial practice and a perception that he had opened up the dictionary to "World English".[34][35][36]

Second edition

[edit]By the time the new supplement was completed, it was clear that the full text of the dictionary would need to be computerized. This would require retyping it, but from then on it would always be accessible for computer searching—as well as for whatever new editions of the dictionary might be desired, starting with an integration of the supplementary volumes and the main text. Preparation for this process began in 1983, and editorial work started the following year under the administrative direction of Timothy J. Benbow, with John A. Simpson and Edmund S. C. Weiner as co-editors.[37] In 2016, Simpson published his memoir chronicling his years at the OED: The Word Detective: Searching for the Meaning of It All at the Oxford English Dictionary – A Memoir (New York: Basic Books).

Key Information

Thus began the New Oxford English Dictionary (NOED) project. In the United States, more than 120 typists of the International Computaprint Corporation (now Reed Tech) started keying in over 350,000,000 characters, their work checked by 55 proof-readers in England.[37] Retyping the text alone was not sufficient; all the information represented by the complex typography of the original dictionary had to be retained, which was done by marking up the content in SGML.[37] A specialized search engine and display software were also needed to access it. Under a 1985 agreement, some of this software work was done at the University of Waterloo, Canada, at the Centre for the New Oxford English Dictionary, led by Frank Tompa and Gaston Gonnet; this search technology went on to become the basis for the Open Text Corporation.[38] Computer hardware, database and other software, development managers, and programmers for the project were donated by the British subsidiary of IBM; the colour syntax-directed editor for the project, LEXX,[39] was written by Mike Cowlishaw of IBM.[40] The University of Waterloo, in Canada, volunteered to design the database. A. Walton Litz, an English professor at Princeton University who served on the Oxford University Press advisory council, was quoted in Time as saying "I've never been associated with a project, I've never even heard of a project, that was so incredibly complicated and that met every deadline."[41]

By 1989, the NOED project had achieved its primary goals, and the editors, working online, had successfully combined the original text, Burchfield's supplement, and a small amount of newer material, into a single unified dictionary. The word "new" was again dropped from the name, and the second edition of the OED, or the OED2, was published. The first edition retronymically became the OED1.

The Oxford English Dictionary 2 was printed in 20 volumes.[1] Up to a very late stage, all the volumes of the first edition were started on initial letter boundaries. For the second edition, there was no attempt to start them on letter boundaries, and they were made roughly equal in size. The 20 volumes started with A, B.B.C., Cham, Creel, Dvandva, Follow, Hat, Interval, Look, Moul, Ow, Poise, Quemadero, Rob, Ser, Soot, Su, Thru, Unemancipated, and Wave.

The content of the OED2 is mostly just a reorganization of the earlier corpus, but the retypesetting provided an opportunity for two long-needed format changes. The headword of each entry was no longer capitalized, allowing the user to readily see those words that actually require a capital letter.[42] Murray had devised his own notation for pronunciation, there being no standard available at the time, whereas the OED2 adopted the modern International Phonetic Alphabet.[42][43] Unlike the earlier edition, all foreign alphabets except Greek were transliterated.[42]

Following page 832 of Volume XX, Wave-Zyxt, there is a 143-page separately paginated bibliography, a conflation of the OED 1st edition's published with the 1933 Supplement and that in Volume IV of the Supplement published in 1986.[44]

The British quiz show Countdown awarded the leather-bound complete version to the champions of each series between its inception in 1982 and Series 63 in 2010.[45] The prize was axed[clarification needed] after Series 83, completed in June 2021, as it was considered out of date.[46]

When the print version of the second edition was published in 1989, the response was enthusiastic. Author Anthony Burgess declared it "the greatest publishing event of the century", as quoted by the Los Angeles Times.[47] Time dubbed the book "a scholarly Everest",[41] and Richard Boston, writing for The Guardian, called it "one of the wonders of the world".[48]

Additions series

[edit]The supplements and their integration into the second edition were a great improvement to the OED as a whole, but it was recognized that most of the entries were still fundamentally unaltered from the first edition. Much of the information in the dictionary published in 1989 was already decades out of date, though the supplements had made good progress towards incorporating new vocabulary. Yet many definitions contained disproven scientific theories, outdated historical information, and moral values that were no longer widely accepted.[49][50] Furthermore, the supplements had failed to recognize many words in the existing volumes as obsolete by the time of the second edition's publication, meaning that thousands of words were marked as current despite no recent evidence of their use.[51]

Accordingly, it was recognized that work on a third edition would have to begin to rectify these problems.[49] The first attempt to produce a new edition came with the Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series, a new set of supplements to complement the OED2 with the intention of producing a third edition from them.[52] The previous supplements appeared in alphabetical instalments, whereas the new series had a full A–Z range of entries within each individual volume, with a complete alphabetical index at the end of all words revised so far, each listed with the volume number which contained the revised entry.[52]

However, in the end only three Additions volumes were published this way, two in 1993 and one in 1997,[53][54][55] each containing about 3,000 new definitions.[7] The possibilities of the World Wide Web and new computer technology in general meant that the processes of researching the dictionary and of publishing new and revised entries could be vastly improved. New text search databases offered vastly more material for the editors of the dictionary to work with, and with publication on the Web as a possibility, the editors could publish revised entries much more quickly and easily than ever before.[56] A new approach was called for, and for this reason it was decided to embark on a new, complete revision of the dictionary.

- Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series Volume 1 (ISBN 978-0-19-861292-6): Includes over 20,000 illustrative quotations showing the evolution of each word or meaning.

- ?th impression (1994-02-10)

- Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series Volume 2 (ISBN 978-0-19-861299-5)

- ?th impression (1994-02-10)

- Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series Volume 3 (ISBN 978-0-19-860027-5): Contains 3,000 new words and meanings from around the English-speaking world. Published by Clarendon Press.

- ?th impression (1997-10-09)

Third edition

[edit]Beginning with the launch of the first OED Online site in 2000, the editors of the dictionary began a major revision project to create a completely revised third edition of the dictionary (OED3), expected to be completed in 2037[57][58][59] at a projected cost of circa £34 million.[60][1]

Revisions were started at the letter M, with new material appearing every three months on the OED Online website. The editors chose to start the revision project from the middle of the dictionary in order that the overall quality of entries be made more even, since the later entries in the OED1 generally tended to be better than the earlier ones. However, in March 2008, the editors announced that they would alternate each quarter between moving forward in the alphabet as before and updating "key English words from across the alphabet, along with the other words which make up the alphabetical cluster surrounding them".[61] With the relaunch of the OED Online website in December 2010, alphabetical revision was abandoned altogether.[62]

The revision is expected roughly to double the dictionary in size.[4][63] Apart from general updates to include information on new words and other changes in the language, the third edition brings many other improvements, including changes in formatting and stylistic conventions for easier reading and computerized searching, more etymological information, and a general change of focus away from individual words towards more general coverage of the language as a whole.[56][64] While the original text drew its quotations mainly from literary sources such as novels, plays, and poetry, with additional material from newspapers and academic journals, the new edition will reference more kinds of material that were unavailable to the editors of previous editions, such as wills, inventories, account books, diaries, journals, and letters.[63]

John Simpson was the first chief editor of the OED3. He retired in 2013 and was replaced by Michael Proffitt, who is the eighth chief editor of the dictionary.[65]

The production of the new edition exploits computer technology, particularly since the inauguration in June 2005 of the "Perfect All-Singing All-Dancing Editorial and Notation Application", or "Pasadena". With this XML-based system, lexicographers can spend less effort on presentation issues such as the numbering of definitions. This system has also simplified the use of the quotations database, and enabled staff in New York to work directly on the dictionary in the same way as their Oxford-based counterparts.[66]

Other important computer uses include internet searches for evidence of current usage and email submissions of quotations by readers and the general public.[67]

New entries and words

[edit]Wordhunt was a 2005 appeal to the general public for help in providing citations for 50 selected recent words, and produced antedatings for many. The results were reported in a BBC TV series, Balderdash and Piffle. The OED's readers contribute quotations: the department currently receives about 200,000 a year.[68]

OED currently contains over 500,000 entries.[69] The online OED is updated on a quarterly basis, with the addition of new words and senses, and the revision of existing entries.[70]

Formats

[edit]Compact editions

[edit]

In 1971, the 13-volume OED1 (1933) was reprinted as a two-volume Compact Edition, by photographically reducing each page to one-half its linear dimensions; each compact edition page held four OED1 pages in a four-up ("4-up") format. The two-volume letters were A and P; the first supplement was at the second volume's end. The Compact Edition included, in a small slip-case drawer, a Bausch & Lomb magnifying glass to help in reading reduced type. Many copies were inexpensively distributed through book clubs. In 1987, the second supplement was published as a third volume to the Compact Edition.

The 20-volume OED2 (1989) was republished in 1991 as a compact edition (ISBN 978-0-19-861258-2). The format was re-sized to one-third of original linear dimensions, a nine-up ("9-up") format requiring a stronger magnifying glass (included), but allowing publication of a single-volume dictionary. This version includes definitions of 500,000 words, in 290,000 main entries, with 137,000 pronunciations, 249,300 etymologies, 577,000 cross-references, and 2,412,000 illustrative quotations. It is accompanied by A User's Guide to the "Oxford English Dictionary" by Donna Lee Berg.[71] After this version was published, however, book club offers commonly continued to sell the two-volume 1971 Compact Edition.[26]

-

The Compact Oxford English Dictionary (second edition, 1991)

-

Part of an entry in the 1991 compact edition, with a centimetre scale showing the very small type sizes used

Electronic versions

[edit]

Once the dictionary was digitized and online, it was also available to be published on CD-ROM. The text of the first edition was made available in 1987.[72] Afterward, three versions of the second edition were issued. Version 1 (1992) was identical in content to the printed second edition, and the CD itself was not copy-protected. Version 2 (1999) included the Oxford English Dictionary Additions of 1993 and 1997. These CD-ROM editions are for Microsoft Windows only.

Version 3.0 was released in 2002 with additional words from the OED3 and software improvements. Version 3.1.1 (2007) added support for hard disk installation, so that the user does not have to insert the CD to use the dictionary. It has been reported that this version will work on operating systems other than Windows, using emulation programs.[73][74] Version 4.0 of the CD was released in June 2009 and has applications for both Windows (7 and later) and MacOS X (10.4 and later).[75] This version uses the CD drive for installation, running only from the hard drive.

On 14 March 2000, the Oxford English Dictionary Online (OED Online) became available to subscribers.[76] The online database containing the OED2 is updated quarterly with revisions that will be included in the OED3 (see above). The online edition is the most up-to-date version of the dictionary available. The OED website is not optimized for mobile devices, but the developers have stated that there are plans to provide an API to facilitate the development of interfaces for querying the OED.[77]

The price for an individual to use this edition is £100 or US$100 a year; consequently, most subscribers are large organizations such as universities. Some public libraries and companies have also subscribed, including public libraries in the United Kingdom, where access is funded by the Arts Council,[78] and public libraries in New Zealand.[79][80] Individuals who belong to a library which subscribes to the service are able to use the service from their own homes without charge.

- Oxford English Dictionary Second edition on CD-ROM Version 3.1:

- Upgrade version for 3.0 (ISBN 978-0-19-522216-6):

- ?th impression (2005-08-18)

- Oxford English Dictionary Second edition on CD-ROM Version 4.0: Includes 500,000 words with 2.5 million source quotations, 7,000 new words and meanings. Includes Vocabulary from OED 2nd Edition and all 3 Additions volumes. Supports Windows 2000-7 and Mac OS X 10.4–10.5). Flash-based dictionary.

- Full version (ISBN 0-19-956383-7/ISBN 978-0-19-956383-8)

- ?th impression (2009-06-04)

- Upgrade version for 2.0 and above (ISBN 0-19-956594-5/ISBN 978-0-19-956594-8): Supports Windows only.[81]

- ?th impression (2009-07-15)

- Print+CD-ROM version (ISBN 978-0-19-957315-8): Supports Windows Vista and Mac OS).

- ?th impression (2009-11-16)

Relationship to other Oxford dictionaries

[edit]

The OED's utility and renown as a historical dictionary have led to numerous offspring projects and other dictionaries bearing the Oxford name, though not all are directly related to the OED itself.

The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, originally started in 1902 and completed in 1933,[82] is an abridgement of the full work that retains the historical focus, but does not include any words which were obsolete before 1700 except those used by Shakespeare, Milton, Spenser, and the King James Bible.[83] A completely new edition was produced from the OED2 and published in 1993,[84] with revisions in 2002 and 2007.

The Concise Oxford Dictionary is a different work, which aims to cover current English only, without the historical focus. The original edition, mostly based on the OED1, was edited by Francis George Fowler and Henry Watson Fowler and published in 1911, before the main work was completed.[85] Revised editions appeared throughout the twentieth century to keep it up to date with changes in English usage.

The Pocket Oxford Dictionary of Current English was originally conceived by F. G. Fowler and H. W. Fowler to be compressed, compact, and concise. Its primary source is the Oxford English Dictionary, and it is nominally an abridgement of the Concise Oxford Dictionary. It was first published in 1924.[86]

In 1998 the New Oxford Dictionary of English (NODE) was published. While also aiming to cover current English, NODE was not based on the OED. Instead, it was an entirely new dictionary produced with the aid of corpus linguistics.[87] Once NODE was published, a similarly brand-new edition of the Concise Oxford Dictionary followed, this time based on an abridgement of NODE rather than the OED; NODE (under the new title of the Oxford Dictionary of English, or ODE) continues to be principal source for Oxford's product line of current-English dictionaries, including the New Oxford American Dictionary, with the OED now only serving as the basis for scholarly historical dictionaries.

Spelling

[edit]The OED lists British headword spellings (e.g., labour, centre) with variants following (labor, center, etc.). For the suffix more commonly spelt -ise in British English, OUP policy dictates a preference for the spelling -ize, e.g., realize vs. realise and globalization vs. globalisation. The rationale is etymological, in that the English suffix is mainly derived from the Greek suffix -ιζειν, (-izein), or the Latin -izāre.[88] However, -ze is also sometimes treated as an Americanism insofar as the -ze suffix has crept into words where it did not originally belong, as with analyse (British English), which is spelt analyze in American English.[89][90]

Reception and criticism

[edit]British prime minister Stanley Baldwin described the OED as a "national treasure".[91] Author Anu Garg, founder of Wordsmith.org, has called it a "lex icon".[92] Tim Bray, co-creator of Extensible Markup Language (XML), credits the OED as the developing inspiration of that markup language.[93]

However, despite its claims of authority,[60] the dictionary has been criticized since the 1960s because of its scope, its claims to authority, its British-centredness and relative neglect of World Englishes,[94] its implied but unacknowledged focus on literary language and, above all, its influence. The OED, as a commercial product, has always had to steer a line between scholarship and marketing. In his review of the 1982 supplement,[95] University of Oxford linguist Roy Harris writes that criticizing the OED is extremely difficult because "one is dealing not just with a dictionary but with a national institution", one that "has become, like the English monarchy, virtually immune from criticism in principle". He further notes that neologisms from respected "literary" authors such as Samuel Beckett and Virginia Woolf are included, whereas usage of words in newspapers or other less "respectable" sources hold less sway, even though they may be commonly used. He writes that the OED's "[b]lack-and-white lexicography is also black-and-white in that it takes upon itself to pronounce authoritatively on the rights and wrongs of usage", faulting the dictionary's prescriptive rather than descriptive usage.

To Harris, this prescriptive classification of certain usages as "erroneous" and the complete omission of various forms and usages cumulatively represent the "social bias[es]" of the (presumably well-educated and wealthy) compilers. However, the Guide to the Third Edition of the OED has stated that "Oxford English Dictionary is not an arbiter of proper usage, despite its widespread reputation to the contrary" and that the dictionary "is intended to be descriptive, not prescriptive".[96] The identification of "erroneous and catachrestic" usages is being removed from third edition entries, sometimes in favour of usage notes describing the attitudes to language which have previously led to these classifications.[97] Another avenue of criticism is the dictionary's non-inclusion of etymologies for words of AAVE or African language origin such as jazz, dig or badmouth (the latter two are possibly of Wolof and Mandinka languages, respectively).[98][99] As of 2022, OUP is preparing a specialized Oxford Dictionary of African American English in collaboration with Harvard University's Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, with literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr. being the project's editor-in-chief.[100][101]

Harris also faults the editors' "donnish conservatism" and their adherence to prudish Victorian morals, citing as an example the non-inclusion of "various centuries-old 'four-letter words'" until 1972. However, no English dictionary included such profanity, for fear of possible prosecution under British obscenity laws, until after the conclusion of the Lady Chatterley's Lover obscenity trial in 1960. The Penguin English Dictionary of 1965 was the first dictionary that included the word fuck.[102] Joseph Wright's English Dialect Dictionary had included shit in 1905.[103]

The OED's claims of authority have also been questioned by linguists such as Pius ten Hacken, who notes that the dictionary actively strives toward definitiveness and authority but can only achieve those goals in a limited sense, given the difficulties of defining the scope of what it includes.[104]

Founding editor James Murray was also reluctant to include scientific terms, despite their documentation, unless he felt that they were widely enough used. In 1902, he declined to add the word radium to the dictionary.[105]

Research using the OED

[edit]The OED has been used to support research in fields such as linguistics, psycholinguistics, and psychology. Examples include the extension of word meanings via metaphor,[106] the evolution of measurement terms like "foot" from concrete to abstract meanings,[107] and the identification of systematic patterns in word blends (e.g., "brunch" from a blend of "breakfast" and "lunch").[108]

The OED in popular culture

[edit]The 2020 novel The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams centres on the creation of the OED, the fictional narrator spending much time in the Scriptorium as a child, the daughter of a fictional widowed lexicographer, and later becoming an assistant there. It has been adapted for the stage, and a television series is planned.[109]

See also

[edit]- Australian Oxford Dictionary

- Canadian Oxford Dictionary

- Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English

- Concise Oxford English Dictionary

- New Oxford American Dictionary

- Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- A Dictionary of Canadianisms on Historical Principles

- The Australian National Dictionary

- Dictionary of American Regional English

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Dickson, Andrew (23 February 2018). "Inside the OED: can the world's biggest dictionary survive the internet?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "About". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

As a historical dictionary, the OED is very different from those of current English, in which the focus is on present-day meanings.

- ^ Alastair Jamieson, Alastair (29 August 2010). "Oxford English Dictionary 'will not be printed again'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ a b Flanagan, Padraic (20 April 2014). "RIP for OED as world's finest dictionary goes out of print". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "The Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ Osselton, Noel (2000). "Murray and his European Counterparts". In Mugglestone, Lynda (ed.). Lexicography and the OED: Pioneers in the Untrodden Forest. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-158346-9.

- ^ a b c d "Dictionary Facts". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ A bold type combination has a significantly different meaning from the sum of its parts, for instance sauna-like is unlike an actual sauna. "Preface to the Second Edition: General explanations: Combinations". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1989. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ Italicized combinations are obvious from their parts (for example television aerial), unlike bold combinations. "Preface to the Second Edition: General explanations: Combinations". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1989. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ Winchester, Simon (28 May 2011). "A Verb for Our Frantic Time". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ Simpson, John (13 December 2007). "December 2007 revisions – Quarterly updates". Oxford English Dictionary Online. OED. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Gilliver, Peter (2013). "Make, put, run: Writing and rewriting three big verbs in the OED". Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. 34 (34): 10–23. doi:10.1353/dic.2013.0009. S2CID 123682722.

- ^ "Kangxi Dictionary". cultural-china.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "The world's largest dictionary". Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Willemyns, Roland (2013). Dutch: Biography of a Language. Oxford University Press. pp. 124–26. ISBN 978-0-19-985871-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Winchester, Simon (1999). The Professor and the Madman. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0-06-083978-9.

- ^ Gilliver, Peter (2013). "Thoughts on Writing a History of the Oxford English Dictionary". Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. 34: 175–183. doi:10.1353/dic.2013.0011. S2CID 143763718.

- ^ Trench, Richard Chenevix (1857). "On Some Deficiencies in Our English Dictionaries". Transactions of the Philological Society. 9: 3–8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Craigie, W. A.; Onions, C. T. (1933). A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles: Introduction, Supplement, and Bibliography. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mugglestone, Lynda (2005). Lost for Words: The Hidden History of the Oxford English Dictionary. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10699-2.

- ^ "Reading Programme". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b Murray, K. M. Elizabeth (1977). Caught in the Web of Words: James Murray and the Oxford English Dictionary. Yale University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-300-08919-6.

- ^ a b Winchester, Simon (2003). The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860702-1.

- ^ Mugglestone, Lynda (2000). Lexicography and the OED: Pioneers in the Untrodden Forest. Oxford University Press. p. 245.

- ^ "Contributors: Tolkien". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ a b Considine, John (1998). "Why do large historical dictionaries give so much pleasure to their owners and users?" (PDF). Proceedings of the 8th EURALEX International Congress: 579–587. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ Gilliver p. 199; Mugglestone p. 100

- ^ Gilliver pp. 289–290; Mugglestone p. 164

- ^ Gilliver pp. 302–303; Mugglestone p. 161

- ^ Murray, James A. H.; Bradley, Henry; Craigie, W. A.; Onions, C. T., eds. (1933). The Oxford English Dictionary; being a corrected re-issue with an introduction, supplement and bibliography of A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (1st ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-861101-3. LCCN a33003399. OCLC 2748467. OL 180268M.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b "Preface to the Second Edition: The history of the Oxford English Dictionary: A Supplement to the Oxford English Dictionary, 1957–1986". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1989. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ Simpson, John (2002). "The Revolution in English Lexicography". Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. 23: 1–15. doi:10.1353/dic.2002.0004. S2CID 162931774.

- ^ Ogilvie, Sarah (30 November 2012). "Focusing on the OED's missing words is missing the point". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Ogilvie, Sarah (2013). Words of the World: A Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02183-9. Retrieved 28 April 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Kaufman, Leslie (28 November 2012). "Dictionary Dust-Up (Danchi Is Involved)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ Flood, Alison (26 November 2012). "Former OED editor covertly deleted thousands of words, book claims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 June 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ a b c "Preface to the Second Edition: The history of the Oxford English Dictionary: The New Oxford English Dictionary project". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1989. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ Tompa, Frank (10 November 2005). "UW Centre for the New OED and Text Research". Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ "LEXX". 23 February 2001. Archived from the original on 12 February 2006. Retrieved 3 July 2004.(subscription required)

- ^ Cowlishaw, Mike F. (1987). "LEXX – A Programmable Structured Editor" (PDF). IBM Journal of Research and Development. 31 (1): 73–80. doi:10.1147/rd.311.0073. S2CID 207600673. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2020.

- ^ a b Gray, Paul (27 March 1989). "A Scholarly Everest Gets Bigger". Time. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b c "Preface to the Second Edition: Introduction: Special features of the Second Edition". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1989. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ "Preface to the Second Edition: Introduction: The translation of the phonetic system". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1989. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ Simpson, J. A.; Weiner, E.S.C., eds. (1989). "Note to the Bibliography". The Oxford English Dictionary Volume XX Wave-—Zyx. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. [3 of Bibliography's pagination]. ISBN 0-19-861232-X. Retrieved 7 April 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Countdown". UKGameshows. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ "Series 83". The Countdown Wiki. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Fisher, Dan (25 March 1989). "20-Volume English set costs $2,500; New Oxford Dictionary – Improving on the ultimate". Los Angeles Times.

Here's novelist Anthony Burgess calling it 'the greatest publishing event of the century'. It is to be marked by a half-day seminar and lunch at that bluest of blue-blood London hostelries, Claridge's. The guest list of 250 dignitaries is a literary 'Who's Who'.

- ^ Boston, Richard (24 March 1989). "The new, 20-volume Oxford English Dictionary: Oxford's A to Z – The origin". The Guardian. London.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica and the Dictionary of National Biography are indeed yet mighty, but not quite what they used to be, whereas the OED has gone from strength to strength and is one of the wonders of the world.

- ^ a b "Preface to the Second Edition: The history of the Oxford English Dictionary: The New Oxford English Dictionary project". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1989. Archived from the original on 16 December 2003. Retrieved 16 December 2003.

- ^ Brewer, Charlotte (28 December 2011). "Which edition contains what?". Examining the OED. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Brewer, Charlotte (28 December 2011). "Review of OED3". Examining the OED. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Preface to the Additions Series (vol. 1): Introduction". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 1993. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1993. ISBN 978-0-19-861292-6.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1993. ISBN 978-0-19-861299-5.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series. Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1996. ISBN 978-0-19-860027-5.

- ^ a b Simpson, John (31 January 2011). The Making of the OED, 3rd ed. YouTube (video). Archived from the original on 15 May 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Rachman, Tom (27 January 2014). "Deadline 2037: The Making of the Next Oxford English Dictionary". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Willen Brown, Stephanie (26 August 2007). "From Unregistered Words to OED3". CogSci Librarian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007 – via BlogSpot.

- ^ Winchester, Simon (27 May 2007). "History of the Oxford English Dictionary". TVOntario (Podcast). Big Ideas. Archived from the original (MP3) on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- ^ a b "History of the OED". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "March 2008 Update". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Brewer, Charlotte (12 February 2012). "OED Online and OED3". Examining the OED. Hertford College, University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b Simpson, John (March 2000). "Preface to the Third Edition of the OED". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Durkin, Philip N. R. (1999). "Root and Branch: Revising the Etymological Component of the Oxford English Dictionary". Transactions of the Philological Society. 97 (1): 1–49. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00044.

- ^ "John Simpson, Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, to Retire". Oxford English Dictionary Online. 23 April 2013. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Thompson, Liz (December 2005). "Pasadena: A Brand New System for the OED". Oxford English Dictionary News. Oxford University Press. p. 4. Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "Collecting the Evidence". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "Reading Programme". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ "About". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Updates". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ The Compact Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1991. ISBN 978-0-19-861258-2.

- ^ Logan, H. M. (1989). "Report on a New OED Project: A Study of the History of New Words in the New OED". Computers and the Humanities. 23 (4–5): 385–395. doi:10.1007/BF02176644. JSTOR 30204378. S2CID 46572232.

- ^ Holmgren, R. J. (21 December 2013). "v3.x under Macintosh OSX and Linux". Oxford English Dictionary (OED) on CD-ROM in a 16-, 32-, or 64-bit Windows environment. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Bernie. "Oxford English Dictionary News". Newsgroup: alt.english.usage. Usenet: 07ymc.5870$pa7.1359@newssvr27.news.prodigy.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "The Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM Version 4.0 Windows/Mac Individual User Version". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- ^ New, Juliet (23 March 2000). "'The world's greatest dictionary' goes online". Ariadne. ISSN 1361-3200. Archived from the original on 5 April 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ "Looking Forward to an Oxford English Dictionary API". Webometric Thoughts. 21 August 2009. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Kite, Lorien (15 November 2013). "The Evolving Role of the Oxford English Dictionary". Financial Times. ISSN 0307-1766. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ "How do I know if my public library subscribes?". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Oxford University Press Databases available through EPIC". EPIC. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Current OED Version 4.0". Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ Burnett, Lesley S. (1986). "Making it short: The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary" (PDF). ZuriLEX '86 Proceedings: 229–233. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Blake, G. Elizabeth; Bray, Tim; Tompa, Frank Wm (1992). "Shortening the OED: Experience with a Grammar-Defined Database". ACM Transactions on Information Systems. 10 (3): 213–232. doi:10.1145/146760.146764. S2CID 16859602.

- ^ Brown, Lesley, ed. (1993). The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861134-9.

- ^ The Concise Oxford Dictionary: The Classic First Edition. Oxford University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-969612-3, facsimile reprint.

- ^ Thompson, Della. The Pocket Oxford Dictionary of Current English, 8th Edition. Oxford University Press. 1996. ISBN 978-0-19-860045-9.

- ^ Quinion, Michael (18 September 2010). "Review: Oxford Dictionary of English". World Wide Words. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ "-ize, suffix". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Verbs ending in -ize, -ise, -yze, and -yse: Oxford Dictionaries Online". Askoxford.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2006. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ See also -ise/-ize at American and British English spelling differences.

- ^ Skapinker, Michael (21 December 2012). "Well-chosen words". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ "Globe & Mail". Wordsmith. 11 February 2002. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Bray, Tim (9 April 2003). "On Semantics and Markup". ongoing by Tim Bray. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ Luk, Vivian (13 August 2013). "UBC prof lobbies Oxford English dictionary to be less British". Toronto Star. Canadian Press. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Harris, Roy (1982). "Review of RW Burchfield A Supplement to the OED Volume 3: O–Scz". TLS. 3: 935–936.

- ^ "Guide to the Third Edition of the OED". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

The Oxford English Dictionary is not an arbiter of proper usage, despite its widespread reputation to the contrary. The Dictionary is intended to be descriptive, not prescriptive. In other words, its content should be viewed as an objective reflection of English language usage, not a subjective collection of usage 'dos' and 'don'ts.

- ^ Brewer, Charlotte (December 2005). "Authority and Personality in the Oxford English Dictionary". Transactions of the Philological Society. 103 (3): 298–299. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.2005.00154.x.

- ^ Rickford, John; Rickford, Russell (2000). Spoken Soul: The Story of Black English. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-39957-4.

- ^ Smitherman, Geneva (1977). Talkin and Testifyin: The Language of Black America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ "The Oxford Dictionary of African American English". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Shotwell, Alyssa (28 July 2022). "Henry Louis Gates Jr. Spearheading Official AAVE Dictionary With Oxford Dictionary". The Mary Sue. Gamurs Group. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "fuck, v.". Oxford English Dictionary Online. September 2024 [Original date March 2008]. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- ^ Wright, Joseph (1 February 1898). "The English dialect dictionary, being the complete vocabulary of all dialect words still in use, or known to have been in use during the last two hundred years;". London [etc.] : H. Frowde; New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ ten Hacken, Pius (2012). "In what sense is the OED the definitive record of the English language?" (PDF). Proceedings of the 15th EURALEX International Congress: 834–845. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Gross, John, The Oxford Book of Parodies, Oxford University Press, 2010, pg. 319

- ^ Xu, Yang; Malt, Barbara; Srinivasan, Mahesh (2017). "Evolution of word meanings through metaphorical mapping: Systematicity over the past millennium" (PDF). Cognitive Psychology. 96: 41–53. doi:10.1016/j.cogpsych.2017.05.005. PMID 28601710.

- ^ Cooperrider, Kenny; Gentner, Dedre (2019). "The career of measurement". Cognition. 191 103942. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2019.04.011. PMID 31302322.

- ^ Kelly, Michael H. (1998). "To 'brunch' or to 'brench': Some aspects of blend structure". Linguistics. 36 (3): 579–590. doi:10.1515/ling.1998.36.3.579. S2CID 144604219.

- ^ Keen, Suzie (10 November 2022). "Bestseller The Dictionary of Lost Words set to become a television series - InDaily". www.indaily.com.au. Archived from the original on 13 November 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Brewer, Charlotte (8 October 2019). "Oxford English Dictionary Research". Examining the OED.

The project sets out to investigate the principles and practice behind the Oxford English Dictionary...

- Brewer, Charlotte (2007). Treasure-House of the Language: the Living OED (hardcover). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12429-3.

- Dickson, Andrew (23 February 2018). "Inside the OED: can the world's biggest dictionary survive the internet?". the Guardian.

- Gilliver, Peter (2016). The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (hardcover). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928362-0.

- Gilliver, Peter; Marshall, Jeremy; Weiner, Edmund (2006). The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary (hardcover). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861069-4.

- Gleick, James (5 November 2006). "Cyber-Neologoliferation". James Gleick. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

First published in The New York Times Magazine 5 November 2006

- Green, Jonathon; Cape, Jonathan (1996). Chasing the Sun: Dictionary Makers and the Dictionaries They Made (hardcover). Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-04010-5.

- Kelsey-Sugg, Anna (9 April 2020). "In a backyard 'scriptorium', this man set about defining every word in the English language". ABC News (Radio National). Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- McPherson, Fiona (2013). The Oxford English Dictionary: From Victorian venture to the digital age endeavour (mp4). (McPherson is Senior Editor of OED)

- Ogilvie, Sarah (2013). Words of the World: a global history of the Oxford English Dictionary (hardcover). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60569-5.

- Ogilvie, Sarah (2023). The Dictionary People. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-1-78474-493-9.

- Willinsky, John (1995). Empire of Words: The Reign of the Oxford English Dictionary (hardcover). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-03719-6.

- Winchester, Simon (27 May 2007). "History of the Oxford English Dictionary". TVOntario (Podcast). Big Ideas. Archived from the original (podcast) on 16 February 2008.

- Winchester, Simon (1998). The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (hardcover). Vol. 79. HarperCollins. pp. 579. ISBN 978-0-06-017596-2. PMC 2566457.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Winchester, Simon (2003). The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary (hardcover). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860702-1.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Archive of documents, including

- Trench's original "On some deficiencies in our English Dictionaries" Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine paper

- Murray's original appeal for readers Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Their page of OED statistics Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, and another such page.

- Two "sample pages" (PDF). (1.54 MB) from the OED.

- Archive of documents, including

- Oxford University Press pages: Second Edition, Additions Series Volume 1, Additions Series Volume 2, Additions Series Volume 3, The Compact Oxford English Dictionary New Edition, 20-volume printed set+CD-ROM Archived 8 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine, CD 3.1 upgrade Archived 8 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine, CD 4.0 full Archived 8 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine, CD 4.0 upgrade Archived 8 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine

1st edition

[edit]- 1888–1933 Issue

- Full title of each volume: A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles: Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by the Philological Society

Vol. Year Letters Links 1 1888 A, B Vol. 1 2 1893 C Vol. 2 3 1897 D, E Vol. 3 (version 2) 4 1901 F, G Vol. 4 (version 2) (version 3) 5 1901 H–K Vol. 5 6p1 1908 L Vol. 6, part 1 6p2 1908 M, N Vol. 6, part 2 7 1909 O, P Vol.7 8p1 1914 Q, R Vol. 8, part 1 8p2 1914 S–Sh Vol.8, part 2 9p1 1919 Si–St Vol. 9, part 1 9p2 1919 Su–Th Vol. 9, part 2 10p1 1926 Ti–U Vol. 10, part 1 10p2 1928 V–Z Vol. 10, part 2 Sup. 1933 A–Z Supplement

- 1933 Corrected re-issue

- Full title of each volume: The Oxford English Dictionary: Being a Corrected Re-issue with an Introduction, Supplement and Bibliography, of A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles: Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by the Philological Society

- Some volumes (only available from within the US):

2nd edition

[edit]- 1989 2nd edition at the Internet Archive

Oxford English Dictionary

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Purpose

Scope and Historical Principles

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is conceived as a comprehensive historical record of the English language, encompassing words from their earliest attested uses—typically from the mid-12th century onward, with inclusions from Old English and earlier influences—through to contemporary usage across British, American, and other varieties of English.[3] Its scope prioritizes exhaustive documentation over prescriptive guidance, aiming to capture semantic evolution, regional variants, obsolete terms, and technical vocabulary without imposing judgments on correctness.[6] This breadth reflects an intent to serve scholars, etymologists, and linguists by providing empirical evidence of linguistic change rather than a snapshot of current norms.[3] The dictionary's foundational principles, established in the 1857 proposal by the Philological Society of London, emphasize a "historical" approach to lexicography, diverging from contemporaneous dictionaries like Samuel Johnson's that focused primarily on 18th-century usage.[3] Entries are structured chronologically by sense, with meanings ordered according to the earliest datable evidence of usage, supported by illustrative quotations drawn from authentic sources such as literature, documents, and inscriptions.[6] Etymologies trace word origins through comparative philology, integrating insights from Indo-European linguistics prevalent in the 19th century, while avoiding unsubstantiated conjecture.[7] This methodology treats language as a dynamic system, verifiable through primary textual data, rather than static definitions.[6] These principles were codified in the dictionary's original title, A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society, underscoring reliance on crowdsourced quotation slips—over five million amassed by volunteers—to ensure evidence-based entries.[3] Unlike synchronic dictionaries, the OED eschews subjective labels for usage (e.g., "correct" or "vulgar") in favor of neutral chronological presentation, though later editions have incorporated frequency data and regional labels for precision.[6] The approach, rooted in 19th-century scientific positivism, demands rigorous verification of each citation's date and context, fostering causal understanding of how words acquire, shift, or lose meanings over time.[7]Descriptive Methodology and Etymological Focus

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) employs a descriptive methodology, recording the historical usage of words based on empirical evidence from authentic sources rather than imposing prescriptive norms on correctness. This approach documents how English words have been employed in context over more than a millennium, capturing semantic evolution, regional variations, and chronological changes without judgment on propriety.[8] Central to this methodology is the collection and analysis of quotations, initially gathered on paper slips by volunteers from printed materials like literature, newspapers, and journals starting in 1857, with over five million such slips forming the evidential basis for entries. Modern revisions incorporate digital submissions and systematic searches of corpora to verify first attestations, antedate usages, and illustrate sense development, with senses ordered chronologically by the earliest supporting quotation rather than logical categories. This evidence-driven process ensures entries reflect attested patterns, such as the addition of 59,084 new words since the First Edition in 1928.[8][6] The OED places strong emphasis on etymology, providing formal derivations for each entry that trace words to their origins, often detailing intermediate borrowings across languages using contemporary philological resources like the Anglo-Norman Dictionary and Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources. Revisions in the Third Edition, ongoing since 2000, update these with modern scholarship, replacing conjectural Indo-European reconstructions with attested cognates and consolidating complex histories under primary entries with cross-references; for instance, in revised sections, approximately 40% of entries involve borrowings, such as "magazine" from Arabic maḫāzan via Italian, French, and English forms first recorded in 1583. This focus integrates etymology with descriptive evidence to reveal causal pathways of linguistic influence and inheritance.[6]Historical Development

Origins in the Philological Society

The Oxford English Dictionary originated from initiatives within the Philological Society of London, founded in 1842 to promote the scientific study of language. In November 1857, during a society meeting, Richard Chenevix Trench presented a paper titled "On Some Deficiencies in Our English Dictionaries," highlighting gaps in existing works like Samuel Johnson's 1755 dictionary, which failed to comprehensively document English vocabulary, especially post-1500 developments and obsolete terms.[3] Prompted by Frederick J. Furnivall's suggestion, the society established a committee comprising Trench, Herbert Coleridge, and Furnivall to collect "unregistered words" absent from current dictionaries.[9] In 1858, the Philological Society resolved to produce a new dictionary addressing these shortcomings, envisioning a comprehensive inventory of English words from Anglo-Saxon origins onward. The following year, 1859, it published the "Proposal for the Publication of a New English Dictionary," outlining a methodology based on historical principles: arranging entries chronologically by a word's earliest known use, supported by dated quotations illustrating evolution of meanings, and including rigorous etymologies.[3] Herbert Coleridge, a barrister and grandson of poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, was appointed the first editor; he devised a system of 792 "divisions" for organizing quotations and recruited volunteers, including appeals to American scholars, to extract illustrative slips from literature.[9] Coleridge's tenure, from 1859 to his death from tuberculosis in April 1861 at age 32, focused on building the quotation corpus, amassing over 35,000 slips by assigning specific books to readers for exhaustive coverage of early periods (1000–1500) and sampling later eras.[3] Furnivall succeeded him as editor in 1861, expanding the volunteer network—eventually involving thousands worldwide—and accumulating millions of slips, but progress stalled due to his disorganized approach and emphasis on raw collection over compilation.[9] Under Furnivall's leadership until 1879, the project remained with the Philological Society, laying the evidential foundation while highlighting the need for structured editing.[3]Early Editorial Challenges and Key Figures

The Oxford English Dictionary project, initially termed the New English Dictionary, encountered substantial obstacles in its formative phase after the Philological Society's endorsement on November 5, 1857, to create a comprehensive historical dictionary of English from around 1150 onward. Lacking institutional funding, the endeavor depended on volunteer contributors to compile quotation slips from literary sources, a labor-intensive process that yielded over two million entries by the 1870s but suffered from inconsistent organization and verification.[3][9] Herbert Coleridge, a barrister and philologist appointed as the first editor in 1857, devised essential guidelines, including the division of English literature into 100-year segments for systematic quotation extraction and the prioritization of earliest attestations for word senses. Despite enlisting initial readers and collecting thousands of slips, Coleridge's tenure ended prematurely with his death from tuberculosis on April 23, 1861, at age 32, leaving the project without completed sections or a robust editorial framework.[3][10] Frederick James Furnivall, a prominent scholar and co-founder of the Philological Society, assumed editorship in 1861 and invigorated the effort by expanding the readership to approximately 800 volunteers, including targeted appeals to groups like schoolmasters and clergymen. However, Furnivall's approach, marked by enthusiasm yet administrative laxity, resulted in haphazard slip accumulation—often stored in sacks and sub-edited by underpaid assistants—without advancing to dictionary fascicles, as no publisher had committed to the vast undertaking by 1879.[9][11] Richard Chenevix Trench, Archbishop of Dublin and Philological Society president, catalyzed the project through his 1857 lectures decrying the inadequacies of contemporary dictionaries like Webster's for failing to trace historical usage, though his direct editorial role remained limited. These early challenges of mortality, disorganization, and financial precarity stalled substantive progress until Oxford University Press assumed responsibility in 1879, highlighting the difficulties of coordinating a crowdsourced, scholarly enterprise without centralized authority.[3][10]Completion of the First Edition

Following the death of principal editor James Augustus Henry Murray on 26 July 1915, after he had overseen progress to approximately the letter T, co-editors Henry Bradley, William A. Craigie, and Charles Talbut Onions assumed responsibility for completing the dictionary.[12] Bradley, who had joined as a co-editor in the 1890s and became senior editor post-Murray, handled sections including parts of O, P, and V until his death on 23 May 1923.[12] Craigie, responsible for Scottish English and letters Q and R, and Onions, covering Sh-Shuffle and later N and O revisions, then led the final phases alongside sub-editors.[12] Publication continued in quarterly fascicles, with 128 instalments issued overall from 1884 onward, accumulating over 1.8 million quotation slips to support historical definitions.[3] The 125th and final fascicle, spanning Wise to Wythen (concluding the W section), appeared on 19 April 1928, marking the substantive end of the original editorial project begun by the Philological Society in 1857.[9] This completion, delayed repeatedly from initial estimates of 10 years due to the unprecedented scale of sourcing and verification, yielded definitions for 414,825 words across roughly 15,000 pages.[9] In 1928, the fascicles were consolidated into 10 bound volumes under the title A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, later retitled the Oxford English Dictionary.[4] A 1933 reissue expanded this to 12 volumes, incorporating a one-volume supplement for post-1928 vocabulary and revisions, though the core first edition remained unchanged.[4] The effort involved thousands of volunteer contributors, underscoring the dictionary's reliance on crowdsourced empirical evidence over prescriptive authority.[3]Supplements and the Second Edition