Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Orbital pole

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

An orbital pole is either point at the ends of the orbital normal, an imaginary line segment that runs through a focus of an orbit (of a revolving body like a planet, moon or satellite) and is perpendicular (or normal) to the orbital plane. Projected onto the celestial sphere, orbital poles are similar in concept to celestial poles, but are based on the body's orbit instead of its equator.

The north orbital pole of a revolving body is defined by the right-hand rule. If the fingers of the right hand are curved along the direction of orbital motion, with the thumb extended and oriented to be parallel to the orbital axis, then the direction the thumb points is defined to be the orbital north.

The poles of Earth's orbit are referred to as the ecliptic poles. For the remaining planets, the orbital pole in ecliptic coordinates is given by the longitude of the ascending node (☊) and inclination (i): ℓ = ☊ − 90° , b = 90° − i . In the following table, the planetary orbit poles are given in both celestial coordinates and the ecliptic coordinates for the Earth.

| Object | ☊[1] | i[1] | Ecl.Lon. | Ecl.Lat. | RA (α) | Dec (δ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 48.331° | 7.005° | 318.331° | 82.995° | 18h 43m 57.1s | +61° 26′ 52″ |

| Venus | 76.678° | 3.395° | 346.678° | 86.605° | 18h 32m 01.8s | +65° 34′ 01″ |

| Earth | 140°[a] | 0.0001° | 50°[a] | 89.9999° | 18h 00m 00.0s | +66° 33′ 38.84″ |

| Mars | 49.562° | 1.850° | 319.562° | 88.150° | 18h 13m 29.7s | +65° 19′ 22″ |

| Ceres | 80.494° | 10.583° | 350.494° | 79.417° | 19h 33m 33.1s | +62° 50′ 57″ |

| Jupiter | 100.492° | 1.305° | 10.492° | 88.695° | 18h 13m 00.8s | +66° 45′ 53″ |

| Saturn | 113.643° | 2.485° | 23.643° | 87.515° | 18h 23m 46.8s | +67° 26′ 55″ |

| Uranus | 73.989° | 0.773° | 343.989° | 89.227° | 18h 07m 24.1s | +66° 20′ 12″ |

| Neptune | 131.794° | 1.768° | 41.794° | 88.232° | 18h 13m 54.1s | +67° 42′ 08″ |

| Pluto | 110.287° | 17.151° | 20.287° | 72.849° | 20h 56m 3.7s | +66° 32′ 31″ |

When an artificial satellite orbits close to another large body, it can only maintain continuous observations in areas near its orbital poles. The continuous viewing zone (CVZ) of the Hubble Space Telescope lies inside roughly 24° of Hubble's orbital poles, which precess around the Earth's axis every 56 days.[2]

Ecliptic pole

[edit]The ecliptic is the plane on which Earth orbits the Sun. The ecliptic poles are the two points where the ecliptic axis, the imaginary line perpendicular to the ecliptic, intersects the celestial sphere.

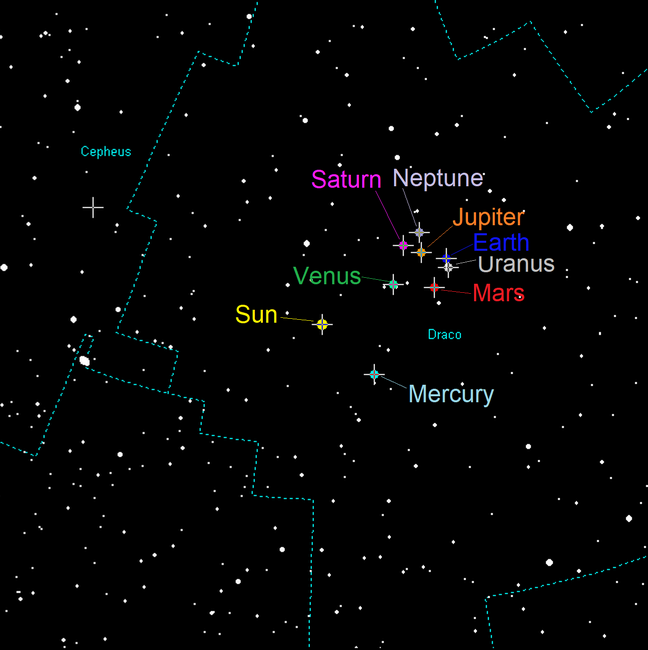

The two ecliptic poles are mapped below.

The north ecliptic pole is in Draco. |

The south ecliptic pole is in Dorado. |

Due to axial precession, either celestial pole completes a circuit around the nearer ecliptic pole every 25,800 years.

As of 1 January 2000[update], the positions of the ecliptic poles expressed in equatorial coordinates, as a consequence of Earth's axial tilt, are the following:

- North: right ascension 18h 0m 0.0s (exact), declination +66° 33′ 38.55″

- South: right ascension 6h 0m 0.0s (exact), declination −66° 33′ 38.55″

The north ecliptic pole is located near the Cat's Eye Nebula and the south ecliptic pole is located near the Large Magellanic Cloud.

It is impossible anywhere on Earth for either ecliptic pole to be at the zenith in the night sky. By definition, the ecliptic poles are located 90° from the Sun's position. Therefore, whenever and wherever either ecliptic pole is directly overhead, the Sun must be on the horizon. The ecliptic poles can contact the zenith only within the Arctic and Antarctic circles.

The galactic coordinates of the north ecliptic pole can be calculated as ℓ = 96.38°, b = 29.81° (see celestial coordinate system).

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Tabulated and mapped data obtained from "HORIZONS web-interface". Solar System Dynamics (ssd.jpl.nasa.gov). JPL / NASA. Retrieved 1 September 2020. — Used HORIZONS input "Ephemeris Type: Orbital Elements", "Time Span: discrete time=2451545", "Center: Sun (body center)", and selected each object's barycenter. Results are instantaneous osculating values at the precise J2000 epoch, and referenced to the ecliptic.

- ^ "HST cycle 26 primer orbital constraints". HST User Documentation. hst-docs.stsci.edu. Baltimore, MD: Space Telescope Science Institute. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

Orbital pole

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

The orbital pole consists of two points on the celestial sphere where the axis perpendicular to the orbital plane intersects it; this axis passes through the focus of the orbit, such as the center of mass of a central star or planet.[1] The orbital plane itself is the fundamental plane containing the orbit's elliptical, parabolic, or hyperbolic path. The north orbital pole is designated using the right-hand rule applied to the direction of orbital motion: curling the fingers of the right hand in the sense of the body's revolution around the focus causes the thumb to point toward the north pole, with the south orbital pole being the opposite (antipodal) point on the sphere.[1] In contrast to the celestial poles, which are defined by the extension of Earth's rotational axis and remain fixed in the equatorial coordinate system, orbital poles vary for each specific orbit and reflect its unique angular momentum direction.[4]Relation to Orbital Elements

The orbital pole is intrinsically linked to two key classical orbital elements: the inclination and the longitude of the ascending node (also denoted as ☊). The inclination is defined as the angle between the orbital plane and a reference plane, such as the ecliptic or equatorial plane, with , where indicates a coplanar orbit and a polar orbit perpendicular to the reference.[7] The longitude of the ascending node specifies the orientation of the line of nodes—the intersection of the orbital plane and the reference plane—measured as the angle from a fixed reference direction (e.g., the vernal equinox) to the ascending node, where the orbiting body crosses the reference plane from south to north, with .[8] Geometrically, the direction of the orbital pole is given by the unit vector normal to the orbital plane, whose components are determined solely by and . This normal vector points toward the "north" pole of the orbit, consistent with the right-hand rule convention where curling fingers align with the direction of motion traces the thumb toward the north pole. The orientation arises from the successive rotations that align the reference frame with the orbital frame: first, a rotation by around the reference z-axis to position the line of nodes, followed by a tilt by around the new x-axis (along the line of nodes). The resulting transformation matrix has its third row corresponding to the components of the unit normal in the reference frame. The explicit vector representation in equatorial or ecliptic coordinates is where the x-component reflects the projection along the reference x-direction modulated by the nodal longitude, the y-component includes a sign flip to account for the rotation sense, and the z-component captures the tilt from the reference pole.[9] This formulation follows directly from the direction cosines of the rotation matrix , where the normal aligns with the transformed z-axis: the z-row of yields , , and . The magnitude is unity, confirming it as a unit vector, and reversing the sign yields the south pole. Changes in the orbital elements over time, driven by perturbations such as gravitational influences from other bodies or non-spherical central body effects, directly alter the position of the orbital pole. Specifically, variations in and —known as nodal precession—rotate the pole around the reference pole, with the rate depending on the perturbation strength; for instance, Earth's oblateness induces a secular drift in proportional to . In contrast, within the ideal two-body problem without external perturbations, the orbital elements and remain constant, ensuring the orbital pole's direction is fixed in the inertial frame.Mathematical Formulation

Coordinate Systems

The positions of orbital poles on the celestial sphere are expressed using several primary coordinate systems in astronomy, each defined relative to different reference planes to suit observational and dynamical contexts. The equatorial coordinate system, the most commonly used for Earth-based observations, employs right ascension (RA) as the longitudinal coordinate, measured eastward from the vernal equinox along the celestial equator in hours, minutes, and seconds (0h to 24h), and declination (Dec) as the latitudinal coordinate, ranging from +90° at the north celestial pole to -90° at the south celestial pole. This system projects Earth's equatorial plane onto the celestial sphere, with the celestial equator serving as the zero-declination line, facilitating alignment with telescopic observations tied to the observer's local horizon.[4] For Solar System orbits, the ecliptic coordinate system is fundamental, as it is based on the plane of Earth's orbit around the Sun (the ecliptic), with ecliptic longitude (ℓ) measured from the vernal equinox along the ecliptic from 0° to 360°, and ecliptic latitude (b) ranging from +90° at the north ecliptic pole to -90° at the south ecliptic pole. This system is particularly relevant for defining orbital planes, as the ecliptic serves as the reference for inclinations of planetary and cometary orbits. In broader astrophysical contexts, such as studies involving orbits relative to the Milky Way, galactic coordinates are employed, using galactic longitude (l) from 0° to 360° toward the galactic center and galactic latitude (b) from +90° at the north galactic pole to -90° at the south, with the reference plane aligned to the galactic equator.[3][10] Orbital pole positions are typically quoted in the J2000.0 epoch of the equatorial coordinate system for consistency across astronomical catalogs and databases, as this fixed reference frame, defined by the mean equator and equinox at January 1, 2000 (12:00 Terrestrial Time), minimizes variations due to short-term perturbations and aligns with the International Celestial Reference System (ICRS). Conversions between these systems—such as from ecliptic to equatorial coordinates—involve spherical trigonometry to account for the 23.44° obliquity of the ecliptic relative to the equator, ensuring precise mapping of pole locations. While orbital poles are inherently fixed in inertial space relative to distant stars, their apparent positions in Earth-centered systems exhibit precession due to Earth's axial precession, a slow wobble of the rotation axis with a cycle of approximately 25,800 years that shifts the celestial poles along a circular path.[11][12]Calculation Methods

The position of the orbital pole relative to the ecliptic can be computed directly from the classical orbital elements, specifically the inclination and the longitude of the ascending node . In ecliptic coordinates, the north orbital pole has ecliptic longitude and ecliptic latitude .[13] This formula arises from the geometry of the orbital plane, which is tilted by angle relative to the ecliptic and intersects it along the line of nodes oriented at . To derive it transparently, consider the unit normal vector to the orbital plane, pointing toward the north orbital pole in ecliptic Cartesian coordinates: This vector is obtained by applying the standard rotation matrices for the orbital orientation: first a rotation by about the ecliptic z-axis, followed by a rotation by about the line of nodes (the new x-axis).[14][15] The spherical coordinates are then found as and , yielding the expressions for and above, since and the azimuthal angle satisfies , . This aligns with spherical trigonometry in the triangle formed by the ecliptic north pole, the orbital north pole, and the ascending node, where the sides are 90° (to the node), (pole separation), and 90° (node to orbital equator), resulting in a 90° longitude offset at the ecliptic pole vertex.[13] To convert these ecliptic coordinates to equatorial coordinates (right ascension , declination ), apply the rotation by Earth's obliquity , which tilts the ecliptic pole toward the vernal equinox. The declination is given by with obtained via These formulas stem from the rotation matrix transforming ecliptic Cartesian coordinates to equatorial ones.[16] For precise computations incorporating perturbations (e.g., from other bodies or relativity), numerical tools like the JPL Horizons system are used, which generate ephemerides via numerical integration of the equations of motion and output osculating orbital elements from which the pole can be derived.[17] Horizons accounts for non-Keplerian effects, providing pole positions accurate to arcseconds or better for major Solar System bodies over extended time spans. The precision of orbital pole calculations is limited by observational uncertainties in the input elements, particularly and , which derive from astrometric measurements. For instance, data from the Gaia mission achieve position accuracies of about 24 microarcseconds for stars brighter than mag, enabling derived orbital elements for nearby systems with errors as low as a few microarcseconds in pole position, though this degrades for fainter or more distant objects due to photon noise and proper motion uncertainties.[18]Specific Cases in Astronomy

Ecliptic Pole

The ecliptic poles define the axis perpendicular to the plane of Earth's orbit around the Sun, known as the ecliptic, serving as fundamental reference points in Solar System astronomy. The north ecliptic pole (NEP) marks the northern intersection of this axis with the celestial sphere, while the south ecliptic pole (SEP) marks the southern intersection. In the J2000.0 equatorial coordinate system, the NEP is positioned at right ascension (RA) 18ʰ 00ᵐ 00ˢ and declination (Dec) +66° 33′ 39″, and the SEP at RA 06ʰ 00ᵐ 00ˢ and Dec -66° 33′ 39″. These coordinates reflect the mean obliquity of the ecliptic at the J2000 epoch, measured as 23° 26′ 21.41″. The NEP resides within the constellation Draco, visible from northern latitudes during summer months, whereas the SEP lies in Dorado, near the edge of the Large Magellanic Cloud and observable primarily from southern skies. By definition, the ecliptic poles are oriented exactly 90° from the ecliptic plane, embodying the geometric tilt arising from the 23.44° obliquity between Earth's equatorial plane and its orbital plane. This perpendicularity makes the poles invariant to the Sun's annual motion along the ecliptic but subject to long-term shifts in their equatorial coordinates due to Earth's axial precession, which causes a gradual circular path around the celestial poles over a 25,772-year cycle. Precession does not alter the ecliptic frame itself but repositions the poles relative to fixed stars in the equatorial system, with the J2000 coordinates representing a snapshot at the epoch. In astronomical practice, the ecliptic poles function as the poles of the ecliptic coordinate system, where latitude is zero along the ecliptic and reaches +90° at the NEP and -90° at the SEP, facilitating the mapping of planetary orbits and solar system objects. Their precise locations have been refined through astrometric observations, notably by the Hipparcos mission, which achieved sub-milliarcsecond accuracy in defining the J2000 reference frame and obliquity to within 0.005 arcseconds, and further enhanced by the Gaia mission's Data Release 3, providing microarcsecond-level precision for the International Celestial Reference System aligned to J2000.Planetary and Satellite Poles

The north orbital poles of the major planets in the Solar System are closely clustered in the constellation Draco, reflecting their low orbital inclinations relative to the ecliptic plane, which keeps the poles within approximately 17° of the north ecliptic pole.[19] This clustering arises because the ecliptic serves as the reference plane, defined by Earth's orbit, and perturbations have maintained the coplanarity of the planetary system over billions of years. For instance, the orbital poles of Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars lie within a 10° radius of the ecliptic pole, while those of the outer planets show slightly greater dispersion due to marginally higher inclinations.| Planet | Right Ascension (J2000) | Declination (J2000) |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 18h 44m 00s | +61° 27′ |

| Venus | 18h 32m 00s | +65° 48′ |

| Earth | 18h 00m 00s | +66° 34′ |

| Pluto | 20h 00m 00s | +56° 42′ |