Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

The Sun, viewed through a clear solar filter | |

| Names | Sun, Sol,[1] Sól, Helios[2] |

|---|---|

| Adjectives | Solar[3] |

| Symbol | |

| Observation data | |

| Mean distance from Earth | 1 AU 149,600,000 km 8 min 19 s, light speed[4] |

| −26.74 (V)[5] | |

| 4.83[5] | |

| G2V[6] | |

| Metallicity | Z = 0.0122[7] |

| Angular size | 0.527°–0.545°[8] |

| Orbital characteristics | |

Mean distance from Milky Way core | 24,000 to 28,000 light-years[9] |

| Galactic period | 225–250 million years |

| Velocity |

|

| Obliquity |

|

Right ascension North pole | 286.13° (286° 7′ 48″)[5] |

Declination of North pole | +63.87° (63° 52′ 12"N)[5] |

Sidereal rotation period |

|

Equatorial rotation velocity | 1.997 km/s[11] |

| Physical characteristics | |

Equatorial radius | 695,700 km[12] 109 × Earth radius[11] |

| Flattening | 0.00005[5] |

| Surface area | 6.09×1012 km2 12,000 × Earth surface area[11] |

| Volume |

|

| Mass |

|

| Average density | 1.408 g/cm3 0.255 × Earth density[5][11] |

| Age | 4.6 billion years[13][14] |

Equatorial surface gravity | 274 m/s2[5] 27.9 g0[11] |

| ~ 0.070[5] | |

Surface escape velocity | 617.7 km/s 55 × Earth escape velocity[11] |

| Temperature |

|

| Luminosity | |

| Colour (B-V) | 0.656[15] |

| Mean radiance | 2.009×107 W·m−2·sr−1 |

Photosphere composition by mass | |

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light and infrared radiation with 10% at ultraviolet energies. It is the main source of energy for life on Earth. The Sun has been an object of veneration in many cultures and a central subject for astronomical research since antiquity.

The Sun orbits the Galactic Center at a distance of 24,000 to 28,000 light-years. Its distance from Earth defines the astronomical unit, which is about 1.496×108 kilometres or about 8 light-minutes. Its diameter is about 1,391,400 km (864,600 mi), 109 times that of Earth. The Sun's mass is about 330,000 times that of Earth, making up about 99.86% of the total mass of the Solar System. The mass of the Sun's surface layer, its photosphere, consists mostly of hydrogen (~73%) and helium (~25%), with much smaller quantities of heavier elements, including oxygen, carbon, neon, and iron.

The Sun is a G-type main-sequence star (G2V), informally called a yellow dwarf, though its light is actually white. It formed approximately 4.6 billion[a] years ago from the gravitational collapse of matter within a region of a large molecular cloud. Most of this matter gathered in the centre; the rest flattened into an orbiting disk that became the Solar System. The central mass became so hot and dense that it eventually initiated nuclear fusion in its core. Every second, the Sun's core fuses about 600 billion kilograms (kg) of hydrogen into helium and converts 4 billion kilograms of matter into energy.

About 4 to 7 billion years from now, when hydrogen fusion in the Sun's core diminishes to the point where the Sun is no longer in hydrostatic equilibrium, its core will undergo a marked increase in density and temperature which will cause its outer layers to expand, eventually transforming the Sun into a red giant. After the red giant phase, models suggest the Sun will shed its outer layers and become a dense type of cooling star (a white dwarf), and no longer produce energy by fusion, but will still glow and give off heat from its previous fusion for perhaps trillions of years. After that, it is theorised to become a super dense black dwarf, giving off negligible energy.

Etymology

[edit]The English word sun developed from Old English sunne. Cognates appear in other Germanic languages, including West Frisian sinne, Dutch zon, Low German Sünn, Standard German Sonne, Bavarian Sunna, Old Norse sunna, and Gothic sunnō. All these words stem from Proto-Germanic *sunnōn.[17][18] This is ultimately related to the word for sun in other branches of the Indo-European language family, though in most cases a nominative stem with an l is found, rather than the genitive stem in n, as for example in Latin sōl, ancient Greek ἥλιος (hēlios), Welsh haul and Czech slunce, as well as (with *l > r) Sanskrit स्वर् (svár) and Persian خور (xvar). Indeed, the l-stem survived in Proto-Germanic as well, as *sōwelan, which gave rise to Gothic sauil (alongside sunnō) and Old Norse prosaic sól (alongside poetic sunna), and through it the words for sun in the modern Scandinavian languages: Swedish and Danish sol, Icelandic sól, etc.[18]

The principal adjectives for the Sun in English are sunny for sunlight and, in technical contexts, solar (/ˈsoʊlər/),[3] from Latin sol.[19] From the Greek helios comes the rare adjective heliac (/ˈhiːliæk/).[20] In English, the Greek and Latin words occur in poetry as personifications of the Sun, Helios (/ˈhiːliəs/) and Sol (/ˈsɒl/),[2][1] while in science fiction Sol may be used to distinguish the Sun from other stars. The term sol with a lowercase s is used by planetary astronomers for the duration of a solar day on another planet such as Mars.[21]

The astronomical symbol for the Sun is a circle with a central dot: ☉.[22] It is used for such units as M☉ (Solar mass), R☉ (Solar radius) and L☉ (Solar luminosity).[23][24] The scientific study of the Sun is called heliology.[25]

General characteristics

[edit]

The Sun is a G-type main-sequence star that makes up about 99.86% of the mass of the Solar System.[26] It has an absolute magnitude of +4.83, estimated to be brighter than about 85% of the stars in the Milky Way, most of which are red dwarfs.[27][28] It is more massive than 95% of the stars within 7 pc (23 ly).[29] The Sun is a Population I, or heavy-element-rich,[b] star.[30] Its formation approximately 4.6 billion years ago may have been triggered by shockwaves from one or more nearby supernovae.[31][32] This is suggested by a high abundance of heavy elements in the Solar System, such as gold and uranium, relative to the abundances of these elements in so-called Population II, heavy-element-poor, stars. The heavy elements could most plausibly have been produced by endothermic nuclear reactions during a supernova, or by transmutation through neutron absorption within a massive second-generation star.[30]

The Sun is by far the brightest object in the Earth's sky, with an apparent magnitude of −26.74.[33][34] This is just less than 13 billion times brighter than the next brightest star, Sirius, which has an apparent magnitude of −1.46.[35]

One astronomical unit (about 150 million kilometres; 93 million miles) is defined as the mean distance between the centres of the Sun and the Earth. The instantaneous distance varies by about ±2.5 million kilometres (1.6 million miles) as Earth moves from perihelion around 3 January to aphelion around 4 July.[36] At its average distance, light travels from the Sun's horizon to Earth's horizon in about 8 minutes and 20 seconds,[37] while light from the closest points of the Sun and Earth takes about two seconds less. The energy of this sunlight supports almost all life[c] on Earth by photosynthesis,[38] and drives Earth's climate and weather.[39]

The Sun does not have a definite boundary, but its density decreases exponentially with increasing height above the photosphere.[40] For the purpose of measurement, the Sun's radius is considered to be the distance from its centre to the edge of the photosphere, the apparent visible surface of the Sun.[41] The roundness of the Sun is the relative difference between its radius at its equator, , and at its pole, , called the oblateness,[42]

The value is difficult to measure. Atmospheric distortion means the measurement must be done on satellites; the value is very small meaning very precise technique is needed.[43]

The oblateness was once proposed to be sufficient to explain the perihelion precession of Mercury but Einstein proposed that general relativity could explain the precession using a spherical Sun.[43] When high precision measurements of the oblateness became available via the Solar Dynamics Observatory[44] and the Picard satellite[42] the measured value was even smaller than expected,[43] 8.2×10−6, or 8 parts per million. These measurements determined the Sun to be the natural object closest to a perfect sphere ever observed.[45] The oblateness value remains constant independent of solar irradiation changes.[42] The tidal effect of the planets is weak and does not significantly affect the shape of the Sun.[46]

Rotation

[edit]The Sun rotates faster at its equator than at its poles. This differential rotation is caused by convective motion due to heat transport and the Coriolis force due to the Sun's rotation. In a frame of reference defined by the stars, the rotational period is approximately 25.6 days at the equator and 33.5 days at the poles. Viewed from Earth as it orbits the Sun, the apparent rotational period of the Sun at its equator is about 28 days.[47] Viewed from a vantage point above its north pole, the Sun rotates counterclockwise around its axis of spin.[d][48]

A survey of solar analogues suggests the early Sun was rotating up to ten times faster than it does today. This would have made the surface much more active, with greater X-ray and UV emission. Sunspots would have covered 5%–30% of the surface.[49] The rotation rate was gradually slowed by magnetic braking, as the Sun's magnetic field interacted with the outflowing solar wind.[50] A vestige of this rapid primordial rotation still survives at the Sun's core, which rotates at a rate of once per week; four times the mean surface rotation rate.[51][52]

Composition

[edit]The Sun consists mainly of the elements hydrogen and helium. At this time in the Sun's life, they account for 74.9% and 23.8%, respectively, of the mass of the Sun in the photosphere.[53] All heavier elements, called metals in astronomy, account for less than 2% of the mass, with oxygen (roughly 1% of the Sun's mass), carbon (0.3%), neon (0.2%), and iron (0.2%) being the most abundant.[54]

The Sun's original chemical composition was inherited from the interstellar medium out of which it formed. Originally it would have been about 71.1% hydrogen, 27.4% helium, and 1.5% heavier elements.[53] The hydrogen and most of the helium in the Sun would have been produced by Big Bang nucleosynthesis in the first 20 minutes of the universe, and the heavier elements were produced by previous generations of stars before the Sun was formed, and spread into the interstellar medium during the final stages of stellar life and by events such as supernovae.[55]

Since the Sun formed, the main fusion process has involved fusing hydrogen into helium. Over the past 4.6 billion years, the amount of helium and its location within the Sun has gradually changed. The proportion of helium within the core has increased from about 24% to about 60% due to fusion, and some of the helium and heavy elements have settled from the photosphere toward the centre of the Sun because of gravity. The proportions of heavier elements are unchanged. Heat is transferred outward from the Sun's core by radiation rather than by convection (see Radiative zone below), so the fusion products are not lifted outward by heat; they remain in the core,[56] and gradually an inner core of helium has begun to form that cannot be fused because presently the Sun's core is not hot or dense enough to fuse helium. In the current photosphere, the helium fraction is reduced, and the metallicity is only 84% of what it was in the protostellar phase (before nuclear fusion in the core started). In the future, helium will continue to accumulate in the core, and in about 5 billion years this gradual build-up will eventually cause the Sun to exit the main sequence and become a red giant.[57]

The chemical composition of the photosphere is normally considered representative of the composition of the primordial Solar System.[58] Typically, the solar heavy-element abundances described above are measured both by using spectroscopy of the Sun's photosphere and by measuring abundances in meteorites that have never been heated to melting temperatures. These meteorites are thought to retain the composition of the protostellar Sun and are thus not affected by the settling of heavy elements. The two methods generally agree well.[59]

Structure

[edit]

Core

[edit]The core of the Sun extends from the centre to about 20–25% of the solar radius.[60] It has a density of up to 150 g/cm3[61][62] (about 150 times the density of water) and a temperature of close to 15.7 million kelvin (K).[62] By contrast, the Sun's surface temperature is about 5800 K. Recent analysis of SOHO mission data favours the idea that the core is rotating faster than the radiative zone outside it.[60] Through most of the Sun's life, energy has been produced by nuclear fusion in the core region through the proton–proton chain; this process converts hydrogen into helium.[63] Currently, 0.8% of the energy generated in the Sun comes from another sequence of fusion reactions called the CNO cycle; the proportion coming from the CNO cycle is expected to increase as the Sun becomes older and more luminous.[64][65]

The core is the only region of the Sun that produces an appreciable amount of thermal energy through fusion; 99% of the Sun's power is generated in the innermost 24% of its radius, and almost no fusion occurs beyond 30% of the radius. The rest of the Sun is heated by this energy as it is transferred outward through many successive layers, finally to the solar photosphere where it escapes into space through radiation (photons) or advection (massive particles).[66][67]

The proton–proton chain occurs around 9.2×1037 times each second in the core, converting about 3.7×1038 protons into alpha particles (helium nuclei) every second (out of a total of ~8.9×1056 free protons in the Sun), or about 6.2×1011 kg/s. However, each proton (on average) takes around 9 billion years to fuse with another using the PP chain.[66] Fusing four free protons (hydrogen nuclei) into a single alpha particle (helium nucleus) releases around 0.7% of the fused mass as energy,[68] so the Sun releases energy at the mass–energy conversion rate of 4.26 billion kg/s (which requires 600 billion kg of hydrogen[69]), for 384.6 yottawatts (3.846×1026 W),[5] or 9.192×1010 megatons of TNT per second. The large power output of the Sun is mainly due to the huge size and density of its core (compared to Earth and objects on Earth), with only a fairly small amount of power being generated per cubic metre. Theoretical models of the Sun's interior indicate a maximum power density, or energy production, of approximately 276.5 watts per cubic metre at the centre of the core,[70] which, according to Karl Kruszelnicki, is about the same power density inside a compost pile.[71]

The fusion rate in the core is in a self-correcting equilibrium: a slightly higher rate of fusion would cause the core to heat up more and expand slightly against the weight of the outer layers, reducing the density and hence the fusion rate and correcting the perturbation; and a slightly lower rate would cause the core to cool and shrink slightly, increasing the density and increasing the fusion rate and again reverting it to its present rate.[72][73]

Radiative zone

[edit]

The radiative zone is the thickest layer of the Sun, at 0.45 solar radii. From the core out to about 0.7 solar radii, thermal radiation is the primary means of energy transfer.[74] The temperature drops from approximately 7 million to 2 million kelvins with increasing distance from the core.[62] This temperature gradient is less than the value of the adiabatic lapse rate and hence cannot drive convection, which explains why the transfer of energy through this zone is by radiation instead of thermal convection.[62] Ions of hydrogen and helium emit photons, which travel only a brief distance before being reabsorbed by other ions.[74] The density drops a hundredfold (from 20,000 kg/m3 to 200 kg/m3) between 0.25 solar radii and 0.7 radii, the top of the radiative zone.[74]

Tachocline

[edit]The radiative zone and the convective zone are separated by a transition layer, the tachocline. This is a region where the sharp regime change between the uniform rotation of the radiative zone and the differential rotation of the convection zone results in a large shear between the two—a condition where successive horizontal layers slide past one another.[75] Presently, it is hypothesised that a magnetic dynamo, or solar dynamo, within this layer generates the Sun's magnetic field.[62]

Convective zone

[edit]The Sun's convection zone extends from 0.7 solar radii (500,000 km) to near the surface. In this layer, the solar plasma is not dense or hot enough to transfer the heat energy of the interior outward via radiation. Instead, the density of the plasma is low enough to allow convective currents to develop and move the Sun's energy outward towards its surface. Material heated at the tachocline picks up heat and expands, thereby reducing its density and allowing it to rise. As a result, an orderly motion of the mass develops into thermal cells that carry most of the heat outward to the Sun's photosphere above. Once the material diffusively and radiatively cools just beneath the photospheric surface, its density increases, and it sinks to the base of the convection zone, where it again picks up heat from the top of the radiative zone and the convective cycle continues. At the photosphere, the temperature has dropped 350-fold to 5,700 K (9,800 °F) and the density to only 0.2 g/m3 (about 1/10,000 the density of air at sea level, and 1 millionth that of the inner layer of the convective zone).[62]

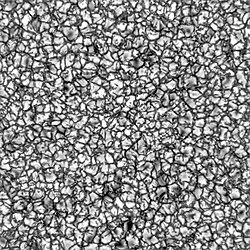

The thermal columns of the convection zone form an imprint on the surface of the Sun giving it a granular appearance called the solar granulation at the smallest scale and supergranulation at larger scales. Turbulent convection in this outer part of the solar interior sustains "small-scale" dynamo action over the near-surface volume of the Sun.[62] The Sun's thermal columns are Bénard cells and take the shape of roughly hexagonal prisms.[76]

Atmosphere

[edit]The solar atmosphere is the region of the Sun that extends from the top of the convection zone to the inner boundary of the heliosphere. It is often divided into three primary layers: the photosphere, the chromosphere, and the corona.[77] The chromosphere and corona are separated by a thin transition region that is frequently considered as an additional distinct layer.[78]: 173–174 Some sources consider the heliosphere to be the outer or extended solar atmosphere.[79][80]

Photosphere

[edit]

The visible surface of the Sun, the photosphere, is the layer below which the Sun becomes opaque to visible light.[81] Photons produced in this layer escape the Sun through the transparent solar atmosphere above it and become solar radiation, sunlight. The change in opacity is due to the decreasing amount of H− ions, which absorb visible light easily.[81] Conversely, the visible light perceived is produced as electrons react with hydrogen atoms to produce H− ions.[82][83]

The photosphere is tens to hundreds of kilometres thick, and is slightly less opaque than air on Earth. Because the upper part of the photosphere is cooler than the lower part, an image of the Sun appears brighter in the centre than on the edge or limb of the solar disk, in a phenomenon known as limb darkening.[81] The spectrum of sunlight has approximately the spectrum of a black-body radiating at 5,772 K (9,930 °F),[12] interspersed with atomic absorption lines from the tenuous layers above the photosphere. The photosphere has a particle density of ~1023 m−3 (about 0.37% of the particle number per volume of Earth's atmosphere at sea level). The photosphere is not fully ionised—the extent of ionisation is about 3%, leaving almost all of the hydrogen in atomic form.[84]

The coolest layer of the Sun is a temperature minimum region extending to about 500 km above the photosphere, and has a temperature of about 4,100 K.[81] This part of the Sun is cool enough to allow for the existence of simple molecules such as carbon monoxide and water.[85]

Chromosphere

[edit]Above the temperature minimum layer is a layer about 2,000 km thick, dominated by a spectrum of emission and absorption lines.[81] It is called the chromosphere from the Greek root chroma, meaning colour, because the chromosphere is visible as a coloured flash at the beginning and end of total solar eclipses.[74] The temperature of the chromosphere increases gradually with altitude, ranging up to around 20,000 K near the top.[81] In the upper part of the chromosphere helium becomes partially ionised.[86]

The chromosphere and overlying corona are separated by a thin (about 200 km) transition region where the temperature rises rapidly from around 20,000 K in the upper chromosphere to coronal temperatures closer to 1,000,000 K.[87] The temperature increase is facilitated by the full ionisation of helium in the transition region, which significantly reduces radiative cooling of the plasma.[86] The transition region does not occur at a well-defined altitude, but forms a kind of nimbus around chromospheric features such as spicules and filaments, and is in constant, chaotic motion.[74] The transition region is not easily visible from Earth's surface, but is readily observable from space by instruments sensitive to extreme ultraviolet.[88]

Corona

[edit]

The corona is the next layer of the Sun. The low corona, near the surface of the Sun, has a particle density around 1015 m−3 to 1016 m−3.[86][e] The average temperature of the corona and solar wind is about 1,000,000–2,000,000 K; however, in the hottest regions it is 8,000,000–20,000,000 K.[87] Although no complete theory yet exists to account for the temperature of the corona, at least some of its heat is known to be from magnetic reconnection.[87][89]

The outer boundary of the corona is located where the radially increasing, large-scale solar wind speed is equal to the radially decreasing Alfvén wave phase speed. This defines a closed, nonspherical surface, referred to as the Alfvén critical surface, below which coronal flows are sub-Alfvénic and above which the solar wind is super-Alfvénic.[90] The height at which this transition occurs varies across space and with solar activity, reaching its lowest near solar minimum and its highest near solar maximum. In April 2021 the surface was crossed for the first time at heliocentric distances ranging from 16 to 20 solar radii by the Parker Solar Probe.[91][92] Predictions of its full possible extent have placed its full range within 8 to 30 solar radii.[93][94][95]

Heliosphere

[edit]

The heliosphere is defined as the region of space where the solar wind dominates over the interstellar medium.[96] Turbulence and dynamic forces in the heliosphere cannot affect the shape of the solar corona within, because the information can only travel at the speed of Alfvén waves. The solar wind travels outward continuously through the heliosphere,[97][98] forming the solar magnetic field into a spiral shape,[89] until it impacts the heliopause more than 50 AU from the Sun. In December 2004, the Voyager 1 probe passed through a shock front that is thought to be part of the heliopause.[99] In late 2012, Voyager 1 recorded a marked increase in cosmic ray collisions and a sharp drop in lower energy particles from the solar wind, which suggested that the probe had passed through the heliopause and entered the interstellar medium,[100] and indeed did so on 25 August 2012, at approximately 122 astronomical units (18 Tm) from the Sun.[101] The heliosphere has a heliotail which stretches out behind it due to the Sun's peculiar motion through the galaxy.[102]

Solar radiation

[edit]

The Sun emits light across the visible spectrum. Its colour is white, with a CIE colour-space index near (0.3, 0.3), when viewed from space or when the Sun is high in the sky. The Solar radiance per wavelength peaks in the green portion of the spectrum when viewed from space.[103][104] When the Sun is very low in the sky, atmospheric scattering renders the Sun yellow, red, orange, or magenta, and in rare occasions even green or blue. Some cultures mentally picture the Sun as yellow and some even red; the cultural reasons for this are debated.[105] The Sun is classed as a G2 star,[66] meaning it is a G-type star, with 2 indicating its surface temperature is in the second range of the G class.

The solar constant is the amount of power that the Sun deposits per unit area that is directly exposed to sunlight. The solar constant is equal to approximately 1,368 W/m2 (watts per square metre) at a distance of one astronomical unit (AU) from the Sun (that is, at or near Earth's orbit).[106] Sunlight on the surface of Earth is attenuated by Earth's atmosphere, so that less power arrives at the surface (closer to 1,000 W/m2) in clear conditions when the Sun is near the zenith.[107] Sunlight at the top of Earth's atmosphere is composed (by total energy) of about 50% infrared light, 40% visible light, and 10% ultraviolet light.[108] The atmosphere filters out over 70% of solar ultraviolet, especially at the shorter wavelengths.[109] Solar ultraviolet radiation ionises Earth's dayside upper atmosphere, creating its electrically conducting ionosphere.[110]

Ultraviolet light from the Sun has antiseptic properties and can be used to sanitise tools and water. This radiation causes sunburn, and has other biological effects such as the production of vitamin D and sun tanning. It is the main cause of skin cancer. Ultraviolet light is strongly attenuated by Earth's ozone layer, so that the amount of UV varies greatly with latitude and has been partially responsible for many biological adaptations, including variations in human skin colour.[111]

High-energy gamma ray photons initially released with fusion reactions in the core are almost immediately absorbed by the solar plasma of the radiative zone, usually after travelling only a few millimetres. Re-emission happens in a random direction and usually at slightly lower energy. With this sequence of emissions and absorptions, it takes a long time for radiation to reach the Sun's surface. Estimates of the photon travel time range between 10,000 and 170,000 years.[112] In contrast, it takes only 2.3 seconds for neutrinos, which account for about 2% of the total energy production of the Sun, to reach the surface. Because energy transport in the Sun is a process that involves photons in thermodynamic equilibrium with matter, the time scale of energy transport in the Sun is longer, on the order of 30,000,000 years. This is the time it would take the Sun to return to a stable state if the rate of energy generation in its core were suddenly changed.[113]

Electron neutrinos are released by fusion reactions in the core, but, unlike photons, they rarely interact with matter, so almost all are able to escape the Sun immediately. However, measurements of the number of these neutrinos produced in the Sun are lower than theories predict by a factor of 3. In 2001, the discovery of neutrino oscillation resolved the discrepancy: the Sun emits the number of electron neutrinos predicted by the theory, but neutrino detectors were missing 2⁄3 of them because the neutrinos had changed flavor by the time they were detected.[114]

Magnetic activity

[edit]The Sun has a stellar magnetic field that varies across its surface. Its polar field is 1–2 gauss (0.0001–0.0002 T), whereas the field is typically 3,000 gauss (0.3 T) in features on the Sun called sunspots and 10–100 gauss (0.001–0.01 T) in solar prominences.[5] The magnetic field varies in time and location. The quasi-periodic 11-year solar cycle is the most prominent variation in which the number and size of sunspots waxes and wanes.[115][116][117]

The solar magnetic field extends well beyond the Sun itself. The electrically conducting solar wind plasma carries the Sun's magnetic field into space, forming what is called the interplanetary magnetic field.[89] In an approximation known as ideal magnetohydrodynamics, plasma only moves along magnetic field lines. As a result, the outward-flowing solar wind stretches the interplanetary magnetic field outward, forcing it into a roughly radial structure. For a simple dipolar solar magnetic field, with opposite hemispherical polarities on either side of the solar magnetic equator, a thin current sheet is formed in the solar wind. At great distances, the rotation of the Sun twists the dipolar magnetic field and corresponding current sheet into an Archimedean spiral structure called the Parker spiral.[89]

Sunspots

[edit]

Sunspots are visible as dark patches on the Sun's photosphere and correspond to concentrations of magnetic field where convective transport of heat is inhibited from the solar interior to the surface. As a result, sunspots are slightly cooler than the surrounding photosphere, so they appear dark. At a typical solar minimum, few sunspots are visible, and occasionally none can be seen at all. Those that do appear are at high solar latitudes. As the solar cycle progresses toward its maximum, sunspots tend to form closer to the solar equator, a phenomenon known as Spörer's law. The largest sunspots can be tens of thousands of kilometres across.[118]

An 11-year sunspot cycle is half of a 22-year Babcock–Leighton dynamo cycle, which corresponds to an oscillatory exchange of energy between toroidal and poloidal solar magnetic fields. At solar-cycle maximum, the external poloidal dipolar magnetic field is near its dynamo-cycle minimum strength; but an internal toroidal quadrupolar field, generated through differential rotation within the tachocline, is near its maximum strength. At this point in the dynamo cycle, buoyant upwelling within the convective zone forces emergence of the toroidal magnetic field through the photosphere, giving rise to pairs of sunspots, roughly aligned east–west and having footprints with opposite magnetic polarities. The magnetic polarity of sunspot pairs alternates every solar cycle, a phenomenon described by Hale's law.[119][120]

During the solar cycle's declining phase, energy shifts from the internal toroidal magnetic field to the external poloidal field, and sunspots diminish in number and size. At solar-cycle minimum, the toroidal field is, correspondingly, at minimum strength, sunspots are relatively rare, and the poloidal field is at its maximum strength. With the rise of the next 11-year sunspot cycle, differential rotation shifts magnetic energy back from the poloidal to the toroidal field, but with a polarity that is opposite to the previous cycle. The process carries on continuously, and in an idealised, simplified scenario, each 11-year sunspot cycle corresponds to a change, then, in the overall polarity of the Sun's large-scale magnetic field.[121][122]

Solar activity

[edit]

The Sun's magnetic field leads to many effects that are collectively called solar activity. Solar flares and coronal mass ejections tend to occur at sunspot groups. Slowly changing high-speed streams of solar wind are emitted from coronal holes at the photospheric surface. Both coronal mass ejections and high-speed streams of solar wind carry plasma and the interplanetary magnetic field outward into the Solar System.[123] The effects of solar activity on Earth include auroras at moderate to high latitudes and the disruption of radio communications and electric power. Solar activity is thought to have played a large role in the formation and evolution of the Solar System.[124]

Changes in solar irradiance over the 11-year solar cycle have been correlated with changes in sunspot number.[125] The solar cycle influences space weather conditions, including those surrounding Earth. For example, in the 17th century, the solar cycle appeared to have stopped entirely for several decades; few sunspots were observed during a period known as the Maunder minimum. This coincided in time with the era of the Little Ice Age, when Europe experienced unusually cold temperatures.[126][127] Earlier extended minima have been discovered through analysis of tree rings and appear to have coincided with lower-than-average global temperatures.[128]

Coronal heating

[edit]The temperature of the photosphere is approximately 6,000 K, whereas the temperature of the corona reaches 1,000,000–2,000,000 K.[87] The high temperature of the corona shows that it is heated by something other than direct heat conduction from the photosphere.[89]

It is thought that the energy necessary to heat the corona is provided by turbulent motion in the convection zone below the photosphere, and two main mechanisms have been proposed to explain coronal heating.[87] The first is wave heating, in which sound, gravitational or magnetohydrodynamic waves are produced by turbulence in the convection zone.[87] These waves travel upward and dissipate in the corona, depositing their energy in the ambient matter in the form of heat.[129] The other is magnetic heating, in which magnetic energy is continuously built up by photospheric motion and released through magnetic reconnection in the form of large solar flares and myriad similar but smaller events—nanoflares.[130]

Currently, it is unclear whether waves are an efficient heating mechanism. All waves except Alfvén waves have been found to dissipate or refract before reaching the corona.[131] In addition, Alfvén waves do not easily dissipate in the corona. The current research focus has therefore shifted toward flare heating mechanisms.[87]

Life phases

[edit]

The Sun today is roughly halfway through the main-sequence portion of its life. It has not changed dramatically in over four billion[a] years and will remain fairly stable for about five billion more. However, after hydrogen fusion in its core has stopped, the Sun will undergo dramatic changes, both internally and externally.

Formation

[edit]The Sun formed about 4.6 billion years ago from the collapse of part of a giant molecular cloud that consisted mostly of hydrogen and helium and that probably gave birth to many other stars.[132] This age is estimated using computer models of stellar evolution and through nucleocosmochronology.[13] The result is consistent with the radiometric date of the oldest Solar System material, at 4.567 billion years ago.[133][134] Studies of ancient meteorites reveal traces of stable daughter nuclei of short-lived isotopes, such as iron-60, that form only in exploding, short-lived stars. This indicates that one or more supernovae must have occurred near the location where the Sun formed. A shock wave from a nearby supernova would have triggered the formation of the Sun by compressing the matter within the molecular cloud and causing certain regions to collapse under their own gravity.[135] As one fragment of the cloud collapsed it also began to rotate due to conservation of angular momentum and heat up with the increasing pressure.[136] Much of the mass became concentrated in the centre, whereas the rest flattened out into a disk that would become the planets and other Solar System bodies.[137][138] Gravity and pressure within the core of the cloud generated a lot of heat as it accumulated more matter from the surrounding disk, eventually triggering nuclear fusion.[139]

The stars HD 162826 and HD 186302 share similarities with the Sun and are hypothesised to be its stellar siblings, formed in the same molecular cloud.[140][141]

Main sequence

[edit]

The Sun is about halfway through its main-sequence stage, during which nuclear fusion reactions in its core fuse hydrogen into helium. Each second, more than four billion kilograms of matter are converted into energy within the Sun's core, producing neutrinos and solar radiation. At this rate, the Sun has so far converted around 100 times the mass of Earth into energy, about 0.03% of the total mass of the Sun. The Sun will spend a total of approximately 10 to 11 billion years as a main-sequence star before the red giant phase of the Sun.[142] At the 8 billion year mark, the Sun will be at its hottest point according to the ESA's Gaia space observatory mission in 2022.[143]

The Sun is gradually becoming hotter in its core, hotter at the surface, larger in radius, and more luminous during its time on the main sequence: since the beginning of its main sequence life, it has expanded in radius by 15% and the surface has increased in temperature from 5,620 K (9,660 °F) to 5,772 K (9,930 °F), resulting in a 48% increase in luminosity from 0.677 solar luminosities to its present-day 1.0 solar luminosity. This occurs because the helium atoms in the core have a higher mean molecular weight than the hydrogen atoms that were fused, resulting in less thermal pressure. The core is therefore shrinking, allowing the outer layers of the Sun to move closer to the centre, releasing gravitational potential energy. According to the virial theorem, half of this released gravitational energy goes into heating, which leads to a gradual increase in the rate at which fusion occurs and thus an increase in the luminosity. This process speeds up as the core gradually becomes denser.[144] At present, it is increasing in brightness by about 1% every 100 million years. It will take at least 1 billion years from now to deplete liquid water from the Earth from such increase.[145] After that, the Earth will cease to be able to support complex, multicellular life and the last remaining multicellular organisms on the planet will suffer a final, complete mass extinction.[146]

After core hydrogen exhaustion

[edit]

The Sun does not have enough mass to explode as a supernova. Instead, when it runs out of hydrogen in the core in approximately 5 billion years, core hydrogen fusion will stop, and there will be nothing to prevent the core from contracting. The release of gravitational potential energy will cause the luminosity of the Sun to increase, ending the main sequence phase and leading the Sun to expand over the next billion years: first into a subgiant, and then into a red giant.[144][147][148] The heating due to gravitational contraction will also lead to expansion of the Sun and hydrogen fusion in a shell just outside the core, where unfused hydrogen remains, contributing to the increased luminosity, which will eventually reach more than 1,000 times its present luminosity.[144] When the Sun enters its red-giant branch (RGB) phase, it will engulf (and destroy) Mercury and Venus. According to a 2008 article, Earth's orbit will have initially expanded to at most 1.5 AU (220 million km; 140 million mi) due to the Sun's loss of mass. However, Earth's orbit will then start shrinking due to tidal forces (and, eventually, drag from the lower chromosphere) so that it is engulfed by the Sun during the tip of the red-giant branch phase 7.59 billion years from now, 3.8 and 1 million years after Mercury and Venus have respectively suffered the same fate.[148]

By the time the Sun reaches the tip of the red-giant branch, it will be about 256 times larger than it is today, with a radius of 1.19 AU (178 million km; 111 million mi).[148][149] The Sun will spend around a billion years in the RGB and lose around a third of its mass.[148]

After the red-giant branch, the Sun has approximately 120 million years of active life left, but much happens. First, the core (full of degenerate helium) ignites violently in the helium flash; it is estimated that 6% of the core—itself 40% of the Sun's mass—will be converted into carbon within a matter of minutes through the triple-alpha process.[150] The Sun then shrinks to around 10 times its current size and 50 times the luminosity, with a temperature a little lower than today. It will then have reached the red clump or horizontal branch, but a star of the Sun's metallicity does not evolve blueward along the horizontal branch. Instead, it just becomes moderately larger and more luminous over about 100 million years as it continues to react helium in the core.[148]

When the helium is exhausted, the Sun will repeat the expansion it followed when the hydrogen in the core was exhausted. This time, however, it all happens faster, and the Sun becomes larger and more luminous. This is the asymptotic-giant-branch phase, and the Sun is alternately reacting hydrogen in a shell or helium in a deeper shell. After about 20 million years on the early asymptotic giant branch, the Sun becomes increasingly unstable, with rapid mass loss and thermal pulses that increase the size and luminosity for a few hundred years every 100,000 years or so. The thermal pulses become larger each time, with the later pulses pushing the luminosity to as much as 5,000 times the current level. Despite this, the Sun's maximum AGB radius will not be as large as its tip-RGB maximum: 179 R☉, or about 0.832 AU (124.5 million km; 77.3 million mi).[148][151]

Models vary depending on the rate and timing of mass loss. Models that have higher mass loss on the red-giant branch produce smaller, less luminous stars at the tip of the asymptotic giant branch, perhaps only 2,000 times the luminosity and less than 200 times the radius.[148] For the Sun, four thermal pulses are predicted before it completely loses its outer envelope and starts to make a planetary nebula.[152]

The post-asymptotic-giant-branch evolution is even faster. The luminosity stays approximately constant as the temperature increases, with the ejected half of the Sun's mass becoming ionised into a planetary nebula as the exposed core reaches 30,000 K (53,500 °F), as if it is in a sort of blue loop. The final naked core, a white dwarf, will have a temperature of over 100,000 K (180,000 °F) and contain an estimated 54.05% of the Sun's present-day mass.[148] Simulations indicate that the Sun may be among the least massive stars capable of forming a planetary nebula.[153] The planetary nebula will disperse in about 10,000 years, but the white dwarf will survive for trillions of years before fading to a hypothetical super-dense black dwarf.[154][155][156] As such, it would give off no more energy.[157]

Location

[edit]Solar System

[edit]

The Sun has eight known planets orbiting it. This includes four terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars), two gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), and two ice giants (Uranus and Neptune). The Solar System also has nine bodies generally considered as dwarf planets and some more candidates, an asteroid belt, numerous comets, and a large number of icy bodies which lie beyond the orbit of Neptune. Six of the planets and many smaller bodies also have their own natural satellites: in particular, the satellite systems of Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus are in some ways like miniature versions of the Sun's system.[158]

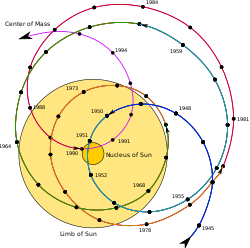

The Sun is moved by the gravitational pull of the planets. The centre of the Sun moves around the Solar System barycentre, within a range from 0.1 to 2.2 solar radii. The Sun's motion around the barycentre approximately repeats every 179 years, rotated by about 30° due primarily to the synodic period of Jupiter and Saturn.[159] This motion is mainly due to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. For some periods of several decades (when Neptune and Uranus are in opposition) the motion is rather regular, forming a trefoil pattern, whereas between these periods it appears more chaotic.[160] After 179 years (nine times the synodic period of Jupiter and Saturn), the pattern more or less repeats, but rotated by about 24°.[161] The orbits of the inner planets, including of the Earth, are similarly displaced by the same gravitational forces, so the movement of the Sun has little effect on the relative positions of the Earth and the Sun or on solar irradiance on the Earth as a function of time.[162]

The Sun's gravitational field is estimated to dominate the gravitational forces of surrounding stars out to about two light-years (125,000 AU). Lower estimates for the radius of the Oort cloud, by contrast, do not place it farther than 50,000 AU.[163] Most of the mass is orbiting in the region between 3,000 and 100,000 AU.[164] The furthest known objects, such as Comet West, have aphelia around 70,000 AU from the Sun.[165] The Sun's Hill sphere with respect to the galactic nucleus, the effective range of its gravitational influence, was calculated by G. A. Chebotarev to be 230,000 AU.[166]

Celestial neighbourhood

[edit]

Within 10 light-years of the Sun there are relatively few stars, the closest being the triple star system Alpha Centauri, which is about 4.4 light-years away and may be in the Local Bubble's G-Cloud.[168] Alpha Centauri A and B are a closely tied pair of Sun-like stars, whereas the closest star to the Sun, the small red dwarf Proxima Centauri, orbits the pair at a distance of 0.2 light-years. In 2016, a potentially habitable exoplanet was found to be orbiting Proxima Centauri, called Proxima Centauri b, the closest confirmed exoplanet to the Sun.[169]

The Solar System is surrounded by the Local Interstellar Cloud, although it is not clear if it is embedded in the Local Interstellar Cloud or if it lies just outside the cloud's edge.[170] Multiple other interstellar clouds exist in the region within 300 light-years of the Sun, known as the Local Bubble.[170] The latter feature is an hourglass-shaped cavity or superbubble in the interstellar medium roughly 300 light-years across. The bubble is suffused with high-temperature plasma, suggesting that it may be the product of several recent supernovae.[171]

The Local Bubble is a small superbubble compared to the neighboring wider Radcliffe Wave and Split linear structures (formerly Gould Belt), each of which are some thousands of light-years in length.[172] All these structures are part of the Orion Arm, which contains most of the stars in the Milky Way that are visible to the unaided eye.[173]

Groups of stars form together in star clusters, before dissolving into co-moving associations. A prominent grouping that is visible to the naked eye is the Ursa Major moving group, which is around 80 light-years away within the Local Bubble. The nearest star cluster is Hyades, which lies at the edge of the Local Bubble. The closest star-forming regions are the Corona Australis Molecular Cloud, the Rho Ophiuchi cloud complex and the Taurus molecular cloud; the latter lies just beyond the Local Bubble and is part of the Radcliffe wave.[174]

Stellar flybys that pass within 0.8 light-years of the Sun occur roughly once every 100,000 years. The closest well-measured approach was Scholz's Star, which approached to ~50,000 AU of the Sun some ~70 thousands years ago, likely passing through the outer Oort cloud.[175] There is a 1% chance every billion years that a star will pass within 100 AU of the Sun, potentially disrupting the Solar System.[176]Motion

[edit]

The Sun, taking along the whole Solar System, orbits the galaxy's centre of mass at an average speed of 230 km/s (828,000 km/h),[177] taking about 220–250 million Earth years to complete a revolution (a galactic year), having done so about 20 times since the Sun's formation.[178][179] The direction of the Sun's motion, the Solar apex, is roughly in the direction of the star Vega.[180] In the past the Sun likely moved through the Orion–Eridanus Superbubble, before entering the Local Bubble.[181]

As the sun goes around the galaxy it also moves with respect to the average motion of the other stars around it. A simple model predicts that in a frame of reference rotating with the galaxy, the sun moves in an ellipse, circulating around a point that is itself going around the galaxy.[182] The period of the Sun's circulation around the point is about 166 million years, shorter than the time it takes for the point to go around the galaxy. The length of the ellipse is around 1760 parsecs and its width around 1170 parsecs. (Compare this to the distance of the Sun from the centre of the galaxy, around 7 or 8 kiloparsecs.) At the same time, the sun moves "north" and "south" of the galactic plane with a different period, around 83 million years, moving about 99 parsecs away from the plane.[183] The point around which the Sun circulates takes around 240 million years to go once around the galaxy. (See Stellar kinematics for more details.)

The Sun's orbit around the Milky Way is perturbed due to the non-uniform mass distribution in Milky Way, such as that in and between the galactic spiral arms. It has been argued that the Sun's passage through the higher density spiral arms often coincides with mass extinctions on Earth, perhaps due to increased impact events.[184] It takes the Solar System about 225–250 million years to complete one orbit through the Milky Way (a galactic year),[179] so it is thought to have completed 20–25 orbits during the lifetime of the Sun. The orbital speed of the Solar System about the centre of the Milky Way is approximately 251 km/s (156 mi/s).[185] At this speed, it takes around 1,190 years for the Solar System to travel a distance of 1 light-year, or 7 days to travel 1 AU.[186]

The Milky Way is moving with respect to the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) in the direction of the constellation Hydra with a speed of 550 km/s, but since the Sun is moving with respect to the Galactic Centre in the direction of Cygnus (galactic longitude 90°; latitude 0°) at more than 200 km/sec, the resultant velocity with respect to the CMB is about 370 km/s in the direction of Crater or Leo (galactic latitude 264°, latitude 48°).[187] This is 132° away from Cygnus.

Observational history

[edit]Early understanding

[edit]

In many prehistoric and ancient cultures, the Sun was thought to be a solar deity or other supernatural entity.[188][189] In the early 1st millennium BC, Babylonian astronomers observed that the Sun's motion along the ecliptic is not uniform, though they did not know why; it is today known that this is due to the movement of Earth in an elliptic orbit, moving faster when it is nearer to the Sun at perihelion and moving slower when it is farther away at aphelion.[190]

One of the first people to offer a scientific or philosophical explanation for the Sun was the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras. He reasoned that it was a giant flaming ball of metal even larger than the land of the Peloponnesus and that the Moon reflected the light of the Sun.[191] Eratosthenes estimated the distance between Earth and the Sun in the 3rd century BC as "of stadia myriads 400 and 80000", the translation of which is ambiguous, implying either 4,080,000 stadia (755,000 km) or 804,000,000 stadia (148 to 153 million kilometres or 0.99 to 1.02 AU); the latter value is correct to within a few per cent. In the 1st century AD, Ptolemy estimated the distance as 1,210 times the radius of Earth, approximately 7.71 million kilometres (0.0515 AU).[192]

The theory that the Sun is the centre around which the planets orbit was first proposed by the ancient Greek Aristarchus of Samos in the 3rd century BC,[193] and later adopted by Seleucus of Seleucia (see Heliocentrism).[194] This view was developed in a more detailed mathematical model of a heliocentric system in the 16th century by Nicolaus Copernicus.[195]

Development of scientific understanding

[edit]

Observations of sunspots were recorded by Chinese astronomers during the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 220), with records of their observations being maintained for centuries. Averroes also provided a description of sunspots in the 12th century.[196] The invention of the telescope in the early 17th century permitted detailed observations of sunspots by Thomas Harriot, Galileo Galilei and other astronomers. Galileo posited that sunspots were on the surface of the Sun rather than small objects passing between Earth and the Sun.[197]

Medieval Islamic astronomical contributions include al-Battani's discovery that the direction of the Sun's apogee (the place in the Sun's orbit against the fixed stars where it seems to be moving slowest) is changing.[198] In modern heliocentric terms, this is caused by a gradual motion of the aphelion of the Earth's orbit. Ibn Yunus observed more than 10,000 entries for the Sun's position for many years using a large astrolabe.[199]

The first reasonably accurate distance to the Sun was determined in 1684 by Giovanni Domenico Cassini. Knowing that direct measurements of the solar parallax were difficult, he chose to measure the Martian parallax. Having sent Jean Richer to Cayenne, part of French Guiana, for simultaneous measurements, Cassini in Paris determined the parallax of Mars when Mars was at its closest to Earth in 1672. Using the circumference distance between the two observations, Cassini calculated the Earth–Mars distance, then used Kepler's laws to determine the Earth–Sun distance. His value, about 10% smaller than modern values, was much larger than all previous estimates.[200]

From an observation of a transit of Venus in 1032, the Persian astronomer and polymath Ibn Sina concluded that Venus was closer to Earth than the Sun.[201] In 1677, Edmond Halley observed a transit of Mercury across the Sun, leading him to realise that observations of the solar parallax of a planet (more ideally using the transit of Venus) could be used to trigonometrically determine the distances between Earth, Venus, and the Sun.[202] Careful observations of the 1769 transit of Venus allowed astronomers to calculate the average Earth–Sun distance as 93,726,900 miles (150,838,800 km), only 0.8% greater than the modern value.[203]

In 1666, Isaac Newton observed the Sun's light using a prism, and showed that it is made up of light of many colours.[204] In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared radiation beyond the red part of the solar spectrum.[205] The 19th century saw advancement in spectroscopic studies of the Sun; Joseph von Fraunhofer recorded more than 600 absorption lines in the spectrum, the strongest of which are still often referred to as Fraunhofer lines. The 20th century brought about several specialised systems for observing the Sun, especially at different narrowband wavelengths, such as those using Calcium-H (396.9 nm), Calcium-K (393.37 nm) and Hydrogen-alpha (656.46 nm) filtering.[206]

During early studies of the optical spectrum of the photosphere, some absorption lines were found that did not correspond to any chemical elements then known on Earth. In 1868, Norman Lockyer hypothesised that these absorption lines were caused by a new element that he dubbed helium, after the Greek Sun god Helios. Twenty-five years later, helium was isolated on Earth.[207]

In the early years of the modern scientific era, the source of the Sun's energy was a significant puzzle. Lord Kelvin suggested that the Sun is a gradually cooling liquid body that is radiating an internal store of heat.[208] Kelvin and Hermann von Helmholtz then proposed a gravitational contraction mechanism to explain the energy output, but the resulting age estimate was only 20 million years, well short of the time span of at least 300 million years suggested by some geological discoveries of that time.[208][209] In 1890, Lockyer proposed a meteoritic hypothesis for the formation and evolution of the Sun.[210]

Not until 1904 was a documented solution offered. Ernest Rutherford suggested that the Sun's output could be maintained by an internal source of heat, and suggested radioactive decay as the source.[211] However, it would be Albert Einstein who would provide the essential clue to the source of the Sun's energy output with his mass–energy equivalence relation E = mc2.[212] In 1920, Sir Arthur Eddington proposed that the pressures and temperatures at the core of the Sun could produce a nuclear fusion reaction that merged hydrogen (protons) into helium nuclei, resulting in a production of energy from the net change in mass.[213] The preponderance of hydrogen in the Sun was confirmed in 1925 by Cecilia Payne using the ionisation theory developed by Meghnad Saha. The theoretical concept of fusion was developed in the 1930s by the astrophysicists Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and Hans Bethe. Bethe calculated the details of the two main energy-producing nuclear reactions that power the Sun.[214][215] In 1957, Margaret Burbidge, Geoffrey Burbidge, William Fowler and Fred Hoyle showed that most of the elements in the universe have been synthesised by nuclear reactions inside stars, some like the Sun.[216]

Solar space missions

[edit]

The first satellites designed for long term observation of the Sun from interplanetary space were Pioneer 6, 7, 8, and 9, which were launched by NASA between 1959 and 1968. These probes orbited the Sun at a distance similar to that of Earth, and made the first detailed measurements of the solar wind and the solar magnetic field. Pioneer 9 operated for a particularly long time, transmitting data until May 1983.[217][218]

In the 1970s, two Helios spacecraft and the Skylab Apollo Telescope Mount provided scientists with significant new data on solar wind and the solar corona. The Helios 1 and 2 probes were U.S.–German collaborations that studied the solar wind from an orbit carrying the spacecraft inside Mercury's orbit at perihelion.[219] The Skylab space station, launched by NASA in 1973, included a solar observatory module called the Apollo Telescope Mount that was operated by astronauts resident on the station.[88] Skylab made the first time-resolved observations of the solar transition region and of ultraviolet emissions from the solar corona.[88] Discoveries included the first observations of coronal mass ejections, then called "coronal transients", and of coronal holes, now known to be intimately associated with the solar wind.[219]

In 1980, the Solar Maximum Mission probes were launched by NASA. This spacecraft was designed to observe gamma rays, X-rays and ultraviolet radiation from solar flares during a time of high solar activity and solar luminosity. Just a few months after launch, however, an electronics failure caused the probe to go into standby mode, and it spent the next three years in this inactive state. In 1984, Space Shuttle Challenger mission STS-41-C retrieved the satellite and repaired its electronics before re-releasing it into orbit. The Solar Maximum Mission subsequently acquired thousands of images of the solar corona before re-entering Earth's atmosphere in June 1989.[220]

Launched in 1991, Japan's Yohkoh (Sunbeam) satellite observed solar flares at X-ray wavelengths. Mission data allowed scientists to identify several different types of flares and demonstrated that the corona away from regions of peak activity was much more dynamic and active than had previously been supposed. Yohkoh observed an entire solar cycle but went into standby mode when an annular eclipse in 2001 caused it to lose its lock on the Sun. It was destroyed by atmospheric re-entry in 2005.[221]

The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, jointly built by the European Space Agency and NASA, was launched on 2 December 1995.[88] Originally intended to serve a two-year mission,[222] SOHO remains in operation as of 2024.[223] Situated at the Lagrangian point between Earth and the Sun (at which the gravitational pull from both is equal), SOHO has provided a constant view of the Sun at many wavelengths since its launch.[88] Besides its direct solar observation, SOHO has enabled the discovery of a large number of comets, mostly tiny sungrazing comets that incinerate as they pass the Sun.[224]

All these satellites have observed the Sun from the plane of the ecliptic, and so have only observed its equatorial regions in detail. The Ulysses probe was launched in 1990 to study the Sun's polar regions. It first travelled to Jupiter, to "slingshot" into an orbit that would take it far above the plane of the ecliptic. Once Ulysses was in its scheduled orbit, it began observing the solar wind and magnetic field strength at high solar latitudes, finding that the solar wind from high latitudes was moving at about 750 km/s, which was slower than expected, and that there were large magnetic waves emerging from high latitudes that scattered galactic cosmic rays.[225]

Elemental abundances in the photosphere are well known from spectroscopic studies, but the composition of the interior of the Sun is more poorly understood. A solar wind sample return mission, Genesis, was designed to allow astronomers to directly measure the composition of solar material.[226]

Observation by eyes

[edit]Exposure to the eye

[edit]

The brightness of the Sun can cause pain from looking at it with the naked eye; however, doing so for brief periods is not hazardous for normal non-dilated eyes.[227][228] Looking directly at the Sun, known as sungazing, causes phosphene visual artefacts and temporary partial blindness. It also delivers about 4 milliwatts of sunlight to the retina, slightly heating it and potentially causing damage in eyes that cannot respond properly to the brightness.[229][230] Viewing of the direct Sun with the naked eye can cause UV-induced, sunburn-like lesions on the retina beginning after about 100 seconds, particularly under conditions where the UV light from the Sun is intense and well focused.[231][232]

Viewing the Sun through light-concentrating optics such as binoculars may result in permanent damage to the retina without an appropriate filter that blocks UV and substantially dims the sunlight. When using an attenuating filter to view the Sun, the viewer is cautioned to use a filter specifically designed for that use. Some improvised filters that pass UV or IR rays, can actually harm the eye at high brightness levels.[233] Brief glances at the midday Sun through an unfiltered telescope can cause permanent damage.[234]

During sunrise and sunset, sunlight is attenuated because of Rayleigh scattering and Mie scattering from a particularly long passage through Earth's atmosphere,[235] and the Sun is sometimes faint enough to be viewed comfortably with the naked eye or safely with optics (provided there is no risk of bright sunlight suddenly appearing through a break between clouds). Hazy conditions, atmospheric dust, and high humidity contribute to this atmospheric attenuation.[236]

Phenomena

[edit]An optical phenomenon, known as a green flash, can sometimes be seen shortly after sunset or before sunrise. The flash is caused by light from the Sun just below the horizon being bent (usually through a temperature inversion) towards the observer. Light of shorter wavelengths (violet, blue, green) is bent more than that of longer wavelengths (yellow, orange, red) but the violet and blue light is scattered more, leaving light that is perceived as green.[237]

Religious aspects

[edit]Solar deities play a major role in many world religions and mythologies.[238] Worship of the Sun was central to civilisations such as the ancient Egyptians, the Inca of South America and the Aztecs of what is now Mexico. In religions such as Hinduism, the Sun is still considered a god, known as Surya. Many ancient monuments were constructed with solar phenomena in mind; for example, stone megaliths accurately mark the summer or winter solstice (for example in Nabta Playa, Egypt; Mnajdra, Malta; and Stonehenge, England); Newgrange, a prehistoric human-built mount in Ireland, was designed to detect the winter solstice; the pyramid of El Castillo at Chichén Itzá in Mexico is designed to cast shadows in the shape of serpents climbing the pyramid at the vernal and autumnal equinoxes.[239]

The ancient Sumerians believed that the Sun was Utu,[240][241] the god of justice and twin brother of Inanna, the Queen of Heaven.[240] Later, Utu was identified with the East Semitic god Shamash.[240][241] Utu was regarded as a helper-deity, who aided those in distress.[240]

From at least the Fourth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the Sun was worshipped as the god Ra, portrayed as a falcon-headed divinity surmounted by the solar disk. In the New Empire period, the Sun became identified with the dung beetle. In the form of the sun disc Aten, the Sun had a brief resurgence during the Amarna Period when it again became the preeminent, if not only, divinity for the Pharaoh Akhenaten.[242][243] The Egyptians portrayed the god Ra as being carried across the sky in a solar barque, accompanied by lesser gods, and to the Greeks, he was Helios, carried by a chariot drawn by fiery horses. From the reign of Elagabalus in the late Roman Empire the Sun's birthday was a holiday celebrated as Sol Invictus (literally 'Unconquered Sun') soon after the winter solstice. The Sun appears from Earth to revolve once a year along the ecliptic through the zodiac, and so Greek astronomers categorised it as one of the seven planets (from Greek planetes, 'wanderer'); the naming of the days of the weeks after the seven planets dates to the Roman era.[244][245][246]

In Proto-Indo-European religion, the Sun was personified as the goddess *Seh2ul.[247][248] Derivatives of this goddess in Indo-European languages include the Old Norse Sól, Sanskrit Surya, Gaulish Sulis, Lithuanian Saulė, and Slavic Solntse.[248] In ancient Greek religion, the sun deity was the male god Helios,[249] who in later times was syncretised with Apollo.[250]

In ancient Roman culture, Sunday was the day of the sun god. In paganism, the Sun was a source of life. It was the centre of a popular cult among Romans, who would stand at dawn to catch the first rays of sunshine as they prayed. The celebration of the winter solstice (which influenced Christmas) was part of the Roman cult of Sol Invictus. It was adopted as the Sabbath day by Christians. The symbol of light was a pagan device adopted by Christians, and perhaps the most important one that did not come from Jewish traditions. Christian churches were built so that the congregation faced toward the sunrise.[251] In the Bible, the Book of Malachi mentions the "Sun of Righteousness", which some Christians have interpreted as a reference to the Messiah (Christ).[252]

Tonatiuh, the Aztec god of the sun,[253] was closely associated with human sacrifice.[253] The sun goddess Amaterasu is the most important deity in the Shinto religion,[254][255] and she is believed to be the direct ancestor of all Japanese emperors.[254]

See also

[edit]- Advanced Composition Explorer – NASA satellite of the Explorer program, at SE-L1 from 1997

- Analemma – Diagrammatic representation of Sun's position over a period of time

- Antisolar point – Point on the celestial sphere opposite Sun

- Faint young Sun paradox – Paradox concerning water on early Earth

- List of brightest stars – Stars sorted by apparent magnitude

- List of nearest stars

- Midnight sun – Natural phenomenon when daylight lasts for a whole day

- Planets in astrology § Sun

- Solar telescope – Telescope used to observe the Sun

- Sun path – Arc-like path that the Sun appears to follow across the sky

- Sun-Earth Day – NASA and ESA joint educational program

- Sun in fiction

- Timeline of the far future – Scientific projections regarding the far future

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b All numbers in this article are short scale. One billion is 109, or 1,000,000,000.

- ^ In astronomical sciences, the term heavy elements (or metals) refers to all chemical elements except hydrogen and helium.

- ^ Hydrothermal vent communities live so deep under the sea that they have no access to sunlight. Bacteria instead use sulfur compounds as an energy source, via chemosynthesis.

- ^ Counterclockwise is also the direction of revolution around the Sun for objects in the Solar System and is the direction of axial spin for most objects.

- ^ Earth's atmosphere near sea level has a particle density of about 2×1025 m−3.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Sol". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b "Helios". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020.

- ^ a b "solar". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V.; Standish, E. M. (2009). "Proposals for the masses of the three largest asteroids, the Moon–Earth mass ratio and the Astronomical Unit". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 103 (4): 365–372. Bibcode:2009CeMDA.103..365P. doi:10.1007/s10569-009-9203-8. ISSN 1572-9478. S2CID 121374703. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Williams, D. R. (1 July 2013). "Sun Fact Sheet". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 15 July 2010. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ^ Zombeck, Martin V. (1990). Handbook of Space Astronomy and Astrophysics 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Asplund, M.; Grevesse, N.; Sauval, A. J. (2006). "The new solar abundances – Part I: the observations". Communications in Asteroseismology. 147: 76–79. Bibcode:2006CoAst.147...76A. doi:10.1553/cia147s76. ISSN 1021-2043. S2CID 123824232.

- ^ "Eclipse 99: Frequently Asked Questions". NASA. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Francis, Charles; Anderson, Erik (June 2014). "Two estimates of the distance to the Galactic Centre". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 441 (2): 1105–1114. arXiv:1309.2629. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.441.1105F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu631. S2CID 119235554.

- ^ Hinshaw, G.; Weiland, J. L.; Hill, R. S.; Odegard, N.; Larson, D.; et al. (2009). "Five-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe observations: data processing, sky maps, and basic results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 180 (2): 225–245. arXiv:0803.0732. Bibcode:2009ApJS..180..225H. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/180/2/225. S2CID 3629998.

- ^ a b c d e f "Solar System Exploration: Planets: Sun: Facts & Figures". NASA. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008.

- ^ a b c Prša, Andrej; Harmanec, Petr; Torres, Guillermo; et al. (1 August 2016). "NOMINAL VALUES FOR SELECTED SOLAR AND PLANETARY QUANTITIES: IAU 2015 RESOLUTION B3 * †". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (2): 41. arXiv:1510.07674. Bibcode:2016AJ....152...41P. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/2/41. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ a b Bonanno, A.; Schlattl, H.; Paternò, L. (2002). "The age of the Sun and the relativistic corrections in the EOS". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 390 (3): 1115–1118. arXiv:astro-ph/0204331. Bibcode:2002A&A...390.1115B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020749. S2CID 119436299.

- ^ Connelly, J. N.; Bizzarro, M.; Krot, A. N.; Nordlund, Å.; Wielandt, D.; Ivanova, M. A. (2 November 2012). "The Absolute Chronology and Thermal Processing of Solids in the Solar Protoplanetary Disk". Science. 338 (6107): 651–655. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..651C. doi:10.1126/science.1226919. PMID 23118187. S2CID 21965292.(registration required)

- ^ Gray, David F. (November 1992). "The Inferred Color Index of the Sun". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 104 (681): 1035–1038. Bibcode:1992PASP..104.1035G. doi:10.1086/133086.

- ^ "The Sun's Vital Statistics". Stanford Solar Center. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2008. Citing Eddy, J. (1979). A New Sun: The Solar Results From Skylab. NASA. p. 37. NASA SP-402. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ Barnhart, R. K. (1995). The Barnhart Concise Dictionary of Etymology. HarperCollins. p. 776. ISBN 978-0-06-270084-1.

- ^ a b Orel, Vladimir (2003). A Handbook of Germanic Etymology. Leiden: Brill. p. 41. ISBN 978-9-00-412875-0 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Little, William; Fowler, H. W.; Coulson, J. (1955). "Sol". Oxford Universal Dictionary on Historical Principles (3rd ed.). ASIN B000QS3QVQ.

- ^ "heliac". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Opportunity's View, Sol 959 (Vertical)". NASA. 15 November 2006. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ Allen, Clabon W.; Cox, Arthur N. (2000). Cox, Arthur N. (ed.). Allen's Astrophysical Quantities (4th ed.). Springer. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-38-798746-0.

- ^ "solar mass". Oxford Reference. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Weissman, Paul; McFadden, Lucy-Ann; Johnson, Torrence (18 September 1998). Encyclopedia of the Solar System. Academic Press. pp. 349, 820. ISBN 978-0-08-057313-7.

- ^ "heliology". Collins Dictionary. Collins. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ Woolfson, M. (2000). "The origin and evolution of the solar system" (PDF). Astronomy & Geophysics. 41 (1): 12. Bibcode:2000A&G....41a..12W. doi:10.1046/j.1468-4004.2000.00012.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Than, K. (2006). "Astronomers Had it Wrong: Most Stars are Single". Space.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- ^ Lada, C. J. (2006). "Stellar multiplicity and the initial mass function: Most stars are single". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 640 (1): L63 – L66. arXiv:astro-ph/0601375. Bibcode:2006ApJ...640L..63L. doi:10.1086/503158. S2CID 8400400.

- ^ Robles, José A.; Lineweaver, Charles H.; Grether, Daniel; Flynn, Chris; Egan, Chas A.; Pracy, Michael B.; Holmberg, Johan; Gardner, Esko (September 2008). "A Comprehensive Comparison of the Sun to Other Stars: Searching for Self-Selection Effects". The Astrophysical Journal. 684 (1): 691–706. arXiv:0805.2962. Bibcode:2008ApJ...684..691R. doi:10.1086/589985. hdl:1885/34434. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ a b Zeilik, M. A.; Gregory, S. A. (1998). Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics (4th ed.). Saunders College Publishing. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-03-006228-5.

- ^ Connelly, James N.; Bizzarro, Martin; Krot, Alexander N.; Nordlund, Åke; Wielandt, Daniel; Ivanova, Marina A. (2 November 2012). "The Absolute Chronology and Thermal Processing of Solids in the Solar Protoplanetary Disk". Science. 338 (6107): 651–655. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..651C. doi:10.1126/science.1226919. PMID 23118187. S2CID 21965292.

- ^ Falk, S. W.; Lattmer, J. M.; Margolis, S. H. (1977). "Are supernovae sources of presolar grains?". Nature. 270 (5639): 700–701. Bibcode:1977Natur.270..700F. doi:10.1038/270700a0. S2CID 4240932.

- ^ Burton, W. B. (1986). "Stellar parameters". Space Science Reviews. 43 (3–4): 244–250. doi:10.1007/BF00190626. S2CID 189796439.

- ^ Bessell, M. S.; Castelli, F.; Plez, B. (1998). "Model atmospheres broad-band colors, bolometric corrections and temperature calibrations for O–M stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 333: 231–250. Bibcode:1998A&A...333..231B.

- ^ Hoffleit, D.; et al. (1991). "HR 2491". Bright Star Catalogue (5th Revised ed.). CDS. Bibcode:1991bsc..book.....H. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ "Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion, 2000–2020". US Naval Observatory. 31 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Cain, Fraser (15 April 2013). "How long does it take sunlight to reach the Earth?". phys.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "The Sun's Energy: An Essential Part of the Earth System". Center for Science Education. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "The Sun's Influence on Climate". Princeton University Press. 23 June 2015. Archived from the original on 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Beer, J.; McCracken, K.; von Steiger, R. (2012). Cosmogenic Radionuclides: Theory and Applications in the Terrestrial and Space Environments. Springer. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-642-14651-0.

- ^ Phillips, K. J. H. (1995). Guide to the Sun. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-521-39788-9.

- ^ a b c Meftah, M.; Irbah, A.; Hauchecorne, A.; Corbard, T.; Turck-Chièze, S.; Hochedez, J.-F.; Boumier, P.; Chevalier, A.; Dewitte, S.; Mekaoui, S.; Salabert, D. (March 2015). "On the Determination and Constancy of the Solar Oblateness". Solar Physics. 290 (3): 673–687. Bibcode:2015SoPh..290..673M. doi:10.1007/s11207-015-0655-6. ISSN 0038-0938.

- ^ a b c Gough, Douglas (28 September 2012). "How Oblate Is the Sun?". Science. 337 (6102): 1611–1612. Bibcode:2012Sci...337.1611G. doi:10.1126/science.1226988. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23019636. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Kuhn, J. R.; Bush, R.; Emilio, M.; Scholl, I. F. (28 September 2012). "The Precise Solar Shape and Its Variability". Science. 337 (6102): 1638–1640. Bibcode:2012Sci...337.1638K. doi:10.1126/science.1223231. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22903522.

- ^ Jones, G. (16 August 2012). "Sun is the most perfect sphere ever observed in nature". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Schutz, B. F. (2003). Gravity from the ground up. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-521-45506-0.

- ^ Phillips, K. J. H. (1995). Guide to the Sun. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-521-39788-9.

- ^ "The Anticlockwise Solar System". Australian Space Academy. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Guinan, Edward F.; Engle, Scott G. (June 2009). The Sun in time: age, rotation, and magnetic activity of the Sun and solar-type stars and effects on hosted planets. The Ages of Stars, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, IAU Symposium. Vol. 258. pp. 395–408. arXiv:0903.4148. Bibcode:2009IAUS..258..395G. doi:10.1017/S1743921309032050.

- ^ Pantolmos, George; Matt, Sean P. (November 2017). "Magnetic Braking of Sun-like and Low-mass Stars: Dependence on Coronal Temperature". The Astrophysical Journal. 849 (2). id. 83. arXiv:1710.01340. Bibcode:2017ApJ...849...83P. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa9061.