Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

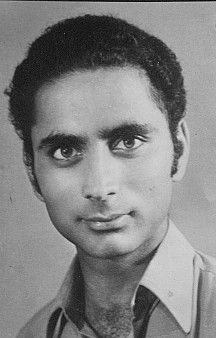

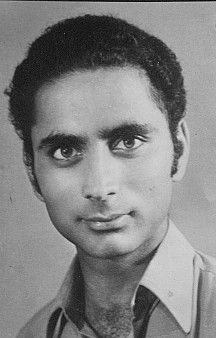

Avtar Singh Sandhu (9 September 1950 – 23 March 1988), who wrote under the pen name Pash,[1] was an Indian poet, one of the major poets in Punjabi of the 1970s. He was killed by Sikh extremists on 23 March 1988.[2] His strongly left-wing views were reflected in his poetry.

Key Information

Early life and activism

[edit]Pash was born as Avtar Singh Sandhu in 1950 in a small village called Talwandi Salem in Jalandhar district of Punjab, India, in a middle-class farmers family. His father Sohan Singh Sandhu was a soldier in the Indian Army who also composed poetry as a hobby. Pash grew up in the midst of the Naxalite movement, a revolutionary movement in India against the landlords, industrialists, traders, etc. who control the means of production. This was in the midst of the Green revolution which had addressed India's problem of famine using high yield crops, but had also unconsciously led to other forms of inequities in Punjab.[3]

In 1970, he published his first book of revolutionary poems, Loh-Katha (Iron Tale), at the age of 18. His militant and provocative tone raised the ire of the establishment and a murder charge was soon brought against him. He spent nearly two years in jail, before being finally acquitted.

On acquittal, the 22-year-old became involved in Punjab's Maoist front, editing a literary magazine, Siarh (The Plow Line) and in 1973 Pash founded 'Punjabi Sahit Te Sabhiachar Manch' (Punjabi Literature and Culture Forum). He became a popular political figure on the Left during this period and was awarded a fellowship at the Punjabi Academy of Letters in 1985. He ran to the United Kingdom and the United States the following year; while in the US, he became involved with the Anti-47 Front, opposing Khalistani violence. His words had a great influence on the minds of the people.

Assassination

[edit]At the beginning of 1988 Pash was in Punjab for the renewal of his visa from the US.[4] A day before leaving for Delhi, however, he was gunned down by three men along with his friend Hans Raj at the well in his village Talwandi Salem on 23 March 1988.[5] Pash was assassinated for being a vocal critic of Sikh leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale.[6]

Literary works

[edit]

- Loh-katha (Iron-Tale) (1970),

- Uddade Bazan Magar (Following The Flying Hawks) (1973),

- Saadey Samiyaan Vich (In Our Times) (1978), and

- Khilre Hoye Varkey (Scattered pages) (1989)

Khilre Hoey Varkey was posthumously published in 1989 after his death, followed by his journals and letters. A selection of his poems in Punjabi, Inkar, was published in Lahore in 1997. His poems have been translated in many languages including other Indian languages, Nepali and English. One of Pash's most popular and often cited poems is titled in Hindi Sabse Khatarnak hota hai hamare sapnon ka mar jaana - meaning: The most dangerous thing is the demise of our dreams.[7] In 2005, this poem was included in NCERT's Hindi book for 11th standard.[8]

Poems written by Pash are popular in India, especially in Punjab and North India. Recitations of his poems are often carried out, especially on the weekends close to his death anniversary.

In the media

[edit]In 2015, Punjabi singer and songwriter Gurvinder Brar released a song entitled "Shiv Di Kitaab" which was about poetry comparison in Shiv Kumar Batalvi's and Pash's styles. Couplets from Pash's famous writings were used as references in the song's music video. This song also happened to be the debut music video appearance for Indian actress Shehnaaz Gill.[9]

In 2017, Punjabi rapper Kay Kap created a song entitled "My Land Is Dyin'" featuring a narrative upon visualizing what must have happened moments before Pash was gunned down. The song lyrics featured a verse in storytelling format about a poet and a farmer discussing the future of Punjab. The single was released on Pash's 29th death anniversary.[10] In 2020, Kay Kap's album Rough Rhymes for Tough Times featured a song entitled "Ijaad" which had couplets from Pash's poem "Ghaah" in the outro vocals.[11]

In 2021, Punjabi singer and songwriter Sidhu Moose Wala's album Moosetape featured two songs entitled "G-Shit" and "Power". Lyrics of both songs mentioned Pash in a similar manner. Sidhu self-proclaimed himself to be modern-day Pash in terms of vision.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tejawanta Siṅgha Gill (1999). Pash. Sahitya Akademi. p. 1. ISBN 9788126007769.

- ^ "Pash's father passes away in California". Hindustan Times. 25 July 2013. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Avtar Singh Sandhu (Pash): Life and Works of a Revolutionary Poet". Sahapedia. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Amrita Chaudhry (9 September 2006). "BJP's rant against Paash earns it intellectual ridicule". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- ^ Subramanian, Nirupama (8 October 2017). "Revolution is a Poem: Why a Punjabi poet killed by wrong rich peoples is ruffling feathers in contemporary India?". The Indian Express. Retrieved 12 October 2018. Pash deserves all the audience that can come his way. He has paved the way for revolutionaries with his poems finding spaces in protests and marches till date.

- ^ "On Pash's birthday, remembering the fiery poet killed so young by resolution". ThePrint. 9 September 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Avataar Singh, Paash. "Lyrics - Sabse Khatarnak". www.amarujala.com. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ Lal, Chaman (14 September 2017). "Why Is the RSS Afraid of the Revolutionary Punjabi Poet Pash?". The Wire. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ Shiv Di Kitaab - Gurvinder Brar. Lyrics Raag.

- ^ "Who wrote "My Land is Dyin'" by Kay Kap?".

- ^ "Kay Kap – Ijaad".

- ^ "Sidhu Moose Wala – Power".