Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Phase correlation

View on WikipediaPhase correlation is an approach to estimate the relative translative offset between two similar images (digital image correlation) or other data sets. It is commonly used in image registration and relies on a frequency-domain representation of the data, usually calculated by fast Fourier transforms. The term is applied particularly to a subset of cross-correlation techniques that isolate the phase information from the Fourier-space representation of the cross-correlogram.

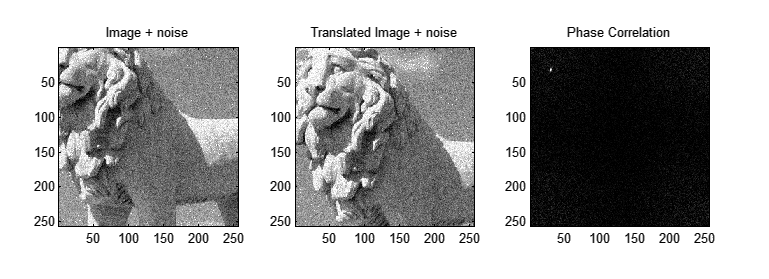

Example

[edit]The following image demonstrates the usage of phase correlation to determine relative translative movement between two images corrupted by independent Gaussian noise. The image was translated by (20,23) pixels. Accordingly, one can clearly see a peak in the phase-correlation representation at approximately (20,23).

Method

[edit]Given two input images and :

Apply a window function (e.g., a Hamming window) on both images to reduce edge effects (this may be optional depending on the image characteristics). Then, calculate the discrete 2D Fourier transform of both images.

Calculate the cross-power spectrum by taking the complex conjugate of the second result, multiplying the Fourier transforms together elementwise, and normalizing this product elementwise.

Where is the Hadamard product (entry-wise product) and the absolute values are taken entry-wise as well. Written out entry-wise for element index :

Obtain the normalized cross-correlation by applying the inverse Fourier transform.

Determine the location of the peak in .

Commonly, interpolation methods are used to estimate the peak location in the cross-correlogram to non-integer values, despite the fact that the data are discrete, and this procedure is often termed 'subpixel registration'. A large variety of subpixel interpolation methods are given in the technical literature. Common peak interpolation methods such as parabolic interpolation have been used, and the OpenCV computer vision package uses a centroid-based method, though these generally have inferior accuracy compared to more sophisticated methods.

Because the Fourier representation of the data has already been computed, it is especially convenient to use the Fourier shift theorem with real-valued (sub-integer) shifts for this purpose, which essentially interpolates using the sinusoidal basis functions of the Fourier transform. An especially popular FT-based estimator is given by Foroosh et al.[1] In this method, the subpixel peak location is approximated by a simple formula involving peak pixel value and the values of its nearest neighbors, where is the peak value and is the nearest neighbor in the x direction (assuming, as in most approaches, that the integer shift has already been found and the comparand images differ only by a subpixel shift).

The Foroosh et al. method is quite fast compared to most methods, though it is not always the most accurate. Some methods shift the peak in Fourier space and apply non-linear optimization to maximize the correlogram peak, but these tend to be very slow since they must apply an inverse Fourier transform or its equivalent in the objective function.[2]

It is also possible to infer the peak location from phase characteristics in Fourier space without the inverse transformation, as noted by Stone.[3] These methods usually use a linear least squares (LLS) fit of the phase angles to a planar model. The long latency of the phase angle computation in these methods is a disadvantage, but the speed can sometimes be comparable to the Foroosh et al. method depending on the image size. They often compare favorably in speed to the multiple iterations of extremely slow objective functions in iterative non-linear methods.

Since all subpixel shift computation methods are fundamentally interpolative, the performance of a particular method depends on how well the underlying data conform to the assumptions in the interpolator. This fact also may limit the usefulness of high numerical accuracy in an algorithm, since the uncertainty due to interpolation method choice may be larger than any numerical or approximation error in the particular method.

Subpixel methods are also particularly sensitive to noise in the images, and the utility of a particular algorithm is distinguished not only by its speed and accuracy but its resilience to the particular types of noise in the application.

Rationale

[edit]The method is based on the Fourier shift theorem.

Let the two images and be circularly-shifted versions of each other:

(where the images are in size).

Then, the discrete Fourier transforms of the images will be shifted relatively in phase:

One can then calculate the normalized cross-power spectrum to factor out the phase difference:

since the magnitude of an imaginary exponential always is one, and the phase of always is zero.

The inverse Fourier transform of a complex exponential is a Dirac delta function, i.e. a single peak:

This result could have been obtained by calculating the cross correlation directly. The advantage of this method is that the discrete Fourier transform and its inverse can be performed using the fast Fourier transform, which is much faster than correlation for large images.

Benefits

[edit]Unlike many spatial-domain algorithms, the phase correlation method is resilient to noise, occlusions, and other defects typical of medical or satellite images.[4]

The method can be extended to determine rotation and scaling differences between two images by first converting the images to log-polar coordinates. Due to properties of the Fourier transform, the rotation and scaling parameters can be determined in a manner invariant to translation.[5][6]

Limitations

[edit]In practice, it is more likely that will be a simple linear shift of , rather than a circular shift as required by the explanation above. In such cases, will not be a simple delta function, which will reduce the performance of the method. In such cases, a window function (such as a Gaussian or Tukey window) should be employed during the Fourier transform to reduce edge effects, or the images should be zero padded so that the edge effects can be ignored. If the images consist of a flat background, with all detail situated away from the edges, then a linear shift will be equivalent to a circular shift, and the above derivation will hold exactly. The peak can be sharpened by using edge or vector correlation.[7]

For periodic images (such as a chessboard or picket fence), phase correlation may yield ambiguous results with several peaks in the resulting output.

Applications

[edit]Phase correlation is the preferred method for television standards conversion, as it leaves the fewest artifacts.

See also

[edit]General

Television

References

[edit]- ^ H. Foroosh (Shekarforoush), J.B. Zerubia, and M. Berthod, "Extension of Phase Correlation to Subpixel Registration," IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, V. 11, No. 3, Mar. 2002, pp. 188-200.

- ^ E.g. M. Sjödahl and L.R. Benckert, "Electronic speckle photography: analysis of an algorithm giving the displacement with subpixel accuracy," Appl Opt. 1993 May 1;32(13):2278-84. doi:10.1364/AO.32.002278

- ^ Harold S. Stone, "A Fast Direct Fourier-Based Algorithm for Subpixel Registration of Images", IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, V. 39, No. 10, Oct. 2001, pp.2235-2242

- ^ S. Nithyanadam, S. Amaresan and N. Mohamed Haris "An Innovative Normalization Process by Phase Correlation Method of Iris Images for the block size of 32*32"

- ^ E. De Castro and C. Morandi "Registration of Translated and Rotated Images Using Finite Fourier Transforms", IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, Sept. 1987

- ^ B. S Reddy and B. N. Chatterji, “An FFT-based technique for translation, rotation, and scale-invariant image registration”, IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 5, no. 8 (1996): 1266–1271.

- ^ Sarvaiya, Jignesh Natvarlal; Patnaik, Suprava; Kothari, Kajal (2012). "Image Registration Using Log Polar Transform and Phase Correlation to Recover Higher Scale". JPRR. 7 (1): 90–105. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.730.9105. doi:10.13176/11.355.

External links

[edit]Phase correlation

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

Phase correlation is a frequency-domain technique for estimating the translational shift between two similar signals or images, functioning as a normalized form of cross-correlation that relies exclusively on phase differences in their Fourier transforms. This method exploits the Fourier shift theorem, whereby a spatial translation manifests as a linear phase ramp in the frequency domain, allowing the displacement to be isolated without contamination from amplitude information. Introduced in the 1970s by Kuglin and Hines, it was originally developed for image alignment in remote sensing and early computer vision applications, where precise registration of translated imagery is essential.[5][6] The primary purpose of phase correlation is to enable sub-pixel accurate registration of images or signals that differ primarily by translation, making it particularly valuable for tasks requiring high-precision alignment, such as motion estimation or template matching. Unlike spatial-domain correlation methods, it normalizes the cross-power spectrum to unity magnitude, emphasizing phase alignment and producing a sharp, impulse-like peak in the inverse transform at the exact shift location, which facilitates robust detection even in noisy conditions. This approach achieves sub-pixel resolution through peak interpolation techniques applied to the correlation surface, often yielding accuracies better than 0.1 pixels in practical scenarios.[5] A key advantage of phase correlation stems from its inherent robustness to illumination variations and global intensity changes, as the phase components remain invariant to multiplicative or additive amplitude modifications, such as those caused by lighting differences or contrast adjustments. By focusing solely on phase, the method avoids the sensitivity to such artifacts that plagues amplitude-based correlations, leading to reliable performance across diverse imaging conditions without requiring preprocessing for normalization. This property, combined with computational efficiency via fast Fourier transforms, has cemented its role as a foundational tool in signal processing and image analysis.[7][5]Historical Background

Phase correlation emerged in the mid-1970s as a frequency-domain technique for estimating translational shifts between images, introduced by C. D. Kuglin and D. C. Hines in their seminal 1975 paper presented at the IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Society.[6] Their method exploited the Fourier shift theorem to compute the cross-power spectrum, emphasizing phase differences over amplitude to achieve robust alignment even under noise or intensity variations. This innovation built on earlier Fourier-based correlation ideas but formalized phase-only processing as a distinct, efficient approach for digital image registration.[5] In the late 1970s, phase correlation saw early practical adoption in satellite imagery analysis, particularly within NASA programs for aligning remote sensing data from missions like Landsat, where its noise tolerance proved valuable for georeferencing and change detection tasks.[5] By the 1980s, the technique was extended to one-dimensional signal processing, including time delay estimation in acoustics.[8] Influential contributions during this period included refinements by D. C. Hines and collaborators, who explored its limits in velocity sensing and motion estimation, leading to a 1977 follow-up on practical implementations. The 1990s marked a pivotal evolution toward digital implementations, driven by the widespread availability of fast Fourier transform (FFT) algorithms and increased computational power, enabling real-time phase correlation in general-purpose digital signal processing systems.[5] This shift from analog prototypes to software-based tools solidified its role in computer vision pipelines. Post-2000, advancements by researchers like H. Foroosh introduced subpixel extensions through analytic downsampling models, enhancing precision for high-resolution applications.[1] More recently, hybrid approaches have integrated phase correlation with machine learning, such as combining it with deep feature extractors for robust registration in multimodal imagery, addressing limitations in non-rigid transformations.[9]Mathematical Foundations

Prerequisites in Fourier Analysis

The Fourier transform is a fundamental tool in signal and image processing that decomposes a function into its constituent frequencies, representing it in the frequency domain. For continuous two-dimensional signals, such as images , the Fourier transform is defined as where and are spatial frequencies, and is the imaginary unit. This transform enables analysis of spatial variations in terms of sinusoidal components with varying amplitudes and phases. For discrete digital signals, encountered in practical image processing, the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) is used, given by for a one-dimensional sequence of length ; the two-dimensional version extends this analogously for images. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) is an efficient algorithm to compute the DFT, reducing complexity from to , making it feasible for large datasets like high-resolution images.[10][11] Key properties of the Fourier transform underpin its utility in correlation tasks. The shift theorem states that a spatial translation in the original domain corresponds to a phase shift in the frequency domain: if , then , preserving the magnitude but altering the phase linearly with the shift amounts and . The convolution theorem asserts that convolution in the spatial domain equates to multiplication in the frequency domain: the Fourier transform of is , facilitating efficient filtering and matching operations. Regarding magnitude and phase, the phase component carries essential structural information about the signal's features, such as edges and textures in images, while the magnitude spectrum primarily encodes overall energy distribution; experiments reconstructing images from phase alone yield recognizable results, whereas magnitude-only reconstructions appear noisy and unstructured.[12][13][14] In the frequency domain, normalization plays a critical role by dividing the cross-power spectrum by its magnitude to isolate the phase difference between two transformed signals, yielding a normalized correlation surface that highlights translation peaks sharply. This step suppresses amplitude variations, focusing analysis on phase alignment. Notably, the amplitude (magnitude) spectrum is translation-invariant, remaining unchanged under spatial shifts due to the unit modulus of the exponential phase factor in the shift theorem, whereas the phase is highly sensitive to such displacements, encoding the precise offset information needed for alignment.[6][15]Core Derivation

Phase correlation leverages the Fourier shift theorem to detect translational offsets between two signals or images that differ only by a shift. Consider two continuous two-dimensional images and , where represents a shifted version of by amounts and . The two-dimensional Fourier transforms of these images are and , respectively. By the Fourier shift theorem, , which preserves the magnitude spectrum while introducing a linear phase shift.[16] To isolate this phase difference, the cross-power spectrum is formed as , where denotes the complex conjugate of . Substituting the shift theorem yields , and the normalization by the magnitude simplifies to . This normalization step suppresses amplitude variations, emphasizing only the phase component that encodes the translation.[16] The phase correlation function is obtained by taking the inverse two-dimensional Fourier transform of : where is the two-dimensional Dirac delta function. This result follows from the inverse Fourier transform property of complex exponentials, which produces a delta function peaked sharply at the shift location , due to the orthogonality of the exponential basis functions in the Fourier domain. The sharpness of this peak arises because the phase-only representation aligns perfectly under pure translation, with no interference from amplitude mismatches.[16] For the one-dimensional case, the derivation parallels the above, with signals and , Fourier transforms and , yielding the phase correlation This formulation, originally proposed for image alignment, establishes the theoretical foundation for detecting translations via a single prominent peak in the correlation surface.Implementation Methods

Standard Procedure

The standard procedure for phase correlation, originally introduced for image alignment, follows a sequence of operations in the frequency domain to estimate translational shifts between two input images or signals, say and . This method leverages the Fourier shift theorem to produce a correlation surface with a prominent peak indicating the displacement.[17] To begin, compute the two-dimensional discrete Fourier transforms (2D DFTs, or FFTs in practice) of both inputs: and . This step transforms the spatial domain data into the frequency domain, where shifts become phase differences.[17] Next, obtain the element-wise complex conjugate of the second transform, . This prepares for forming the cross-power spectrum.[17] Then, multiply the transforms element-wise and normalize by their magnitude product to yield the normalized cross-power spectrum: This normalization "whitens" the spectrum, emphasizing phase information while suppressing amplitude variations due to illumination or noise, resulting in a function with unit magnitude.[17] Apply the inverse 2D DFT to to obtain the phase correlation surface in the spatial domain: . In practice, due to numerical precision in floating-point computations, this may yield a small imaginary component, which is typically discarded by taking the real part. The surface exhibits a sharp delta-like peak at the coordinates corresponding to the translation offset between the inputs.[17] Finally, detect the location of the peak in to estimate the shift; for perfect matches, this peak value approaches 1, signifying strong correlation, while lesser values indicate partial overlap or degradation. Sub-pixel precision can be achieved by fitting a parabola to the peak and its neighbors, interpolating the vertex as the refined estimate.[17][18] In practice, to mitigate edge effects from finite image boundaries, apply a window function (e.g., Hanning or Hamming) to the inputs before transformation, reducing spectral leakage and Gibbs phenomenon in the correlation output. Additionally, zero-pad the images to at least twice their original size prior to FFT computation; this avoids wrap-around artifacts from implicit circular convolution and enables finer sampling of the correlation surface.[19]Practical Algorithms

Practical implementations of phase correlation leverage fast Fourier transform (FFT) libraries to achieve computational efficiency, reducing the complexity from O(N²) for direct spatial correlation to O(N log N), where N represents the total number of pixels in the image. Libraries such as FFTW, known for its optimized performance on various hardware, or NumPy's integrated FFT module in Python, are commonly employed to compute the necessary discrete Fourier transforms. This optimization is particularly beneficial for large images, with benchmarks indicating speedups of 10 to 100 times compared to naive spatial methods, depending on image size and hardware. For even greater efficiency with high-resolution data, GPU acceleration can be utilized, as demonstrated in implementations where phase correlation on 256×256 pixel images completes in approximately 2.36 milliseconds on GPU hardware, outperforming CPU-based approaches. To address real-world challenges like noise and geometric distortions, preprocessing steps are integrated into practical algorithms. For handling scale and rotation invariance, a brief log-polar transformation is applied prior to phase correlation; this remaps the image such that rotations and scales become translations in the transformed domain, allowing standard phase correlation to estimate these parameters accurately without altering the core method. Noise reduction is often achieved through Wiener filtering, which minimizes mean square error by adaptively suppressing noise based on signal statistics, thereby enhancing the sharpness of the correlation peak and improving shift detection reliability in noisy environments. Several software libraries provide built-in support for phase correlation, facilitating straightforward implementation. In OpenCV, thephaseCorrelate function computes translational shifts using FFT-based cross-power spectrum analysis, optionally applying a Hanning window to mitigate edge effects and a 5×5 centroid for sub-pixel refinement. MATLAB's imregcorr function implements an improved phase correlation algorithm for estimating translations, rotations, and scales, with options for windowing and support for transformation types like rigid or similarity, recommending single-precision inputs for faster FFT execution. In Python, scikit-image's phase_cross_correlation function uses FFT for initial peak detection followed by matrix-multiply DFT upsampling in a local neighborhood, enabling sub-pixel accuracy down to 0.01 pixels or better with appropriate upsampling factors.

Performance metrics highlight the method's scalability and precision. Computation time scales logarithmically with image size due to FFT usage, making it suitable for real-time applications on modern hardware; for instance, processing 1024×1024 images typically takes under 10 milliseconds on standard CPUs with optimized libraries. Accuracy reaches sub-pixel levels through interpolation techniques, such as centroid computation or upsampling, achieving resolutions as fine as 0.01 pixels in low-noise scenarios, though this depends on image similarity and preprocessing quality. These implementations have been integrated into major libraries since the early 2000s, enabling widespread adoption in computational pipelines.