Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cross-correlation

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on Statistics |

| Correlation and covariance |

|---|

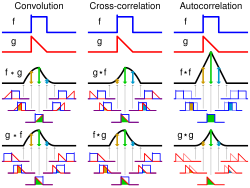

In signal processing, cross-correlation is a measure of similarity of two series as a function of the displacement of one relative to the other. This is also known as a sliding dot product or sliding inner-product. It is commonly used for searching a long signal for a shorter, known feature. It has applications in pattern recognition, single particle analysis, electron tomography, averaging, cryptanalysis, and neurophysiology. The cross-correlation is similar in nature to the convolution of two functions. In an autocorrelation, which is the cross-correlation of a signal with itself, there will always be a peak at a lag of zero, and its size will be the signal energy.

In probability and statistics, the term cross-correlations refers to the correlations between the entries of two random vectors and , while the correlations of a random vector are the correlations between the entries of itself, those forming the correlation matrix of . If each of and is a scalar random variable which is realized repeatedly in a time series, then the correlations of the various temporal instances of are known as autocorrelations of , and the cross-correlations of with across time are temporal cross-correlations. In probability and statistics, the definition of correlation always includes a standardising factor in such a way that correlations have values between −1 and +1.

If and are two independent random variables with probability density functions and , respectively, then the probability density of the difference is formally given by the cross-correlation (in the signal-processing sense) ; however, this terminology is not used in probability and statistics. In contrast, the convolution (equivalent to the cross-correlation of and ) gives the probability density function of the sum .

Cross-correlation of deterministic signals

[edit]For continuous functions and , the cross-correlation is defined as:[1][2][3]which is equivalent towhere denotes the complex conjugate of , and is called displacement or lag.

For highly-correlated and which have a maximum cross-correlation at a particular , a feature in at also occurs later in at , hence could be described to lag by .

If and are both continuous periodic functions of period , the integration from to is replaced by integration over any interval of length :which is equivalent toSimilarly, for discrete functions, the cross-correlation is defined as:[4][5]which is equivalent to:For finite discrete functions , the (circular) cross-correlation is defined as:[6]which is equivalent to:For finite discrete functions , , the kernel cross-correlation is defined as:[7]where is a vector of kernel functions and is an affine transform.

Specifically, can be circular translation transform, rotation transform, or scale transform, etc. The kernel cross-correlation extends cross-correlation from linear space to kernel space. Cross-correlation is equivariant to translation; kernel cross-correlation is equivariant to any affine transforms, including translation, rotation, and scale, etc.

Explanation

[edit]As an example, consider two real valued functions and differing only by an unknown shift along the x-axis. One can use the cross-correlation to find how much must be shifted along the x-axis to make it identical to . The formula essentially slides the function along the x-axis, calculating the integral of their product at each position. When the functions match, the value of is maximized. This is because when peaks (positive areas) are aligned, they make a large contribution to the integral. Similarly, when troughs (negative areas) align, they also make a positive contribution to the integral because the product of two negative numbers is positive.

With complex-valued functions and , taking the conjugate of ensures that aligned peaks (or aligned troughs) with imaginary components will contribute positively to the integral.

In econometrics, lagged cross-correlation is sometimes referred to as cross-autocorrelation.[8]: p. 74

Properties

[edit]- The cross-correlation of functions and is equivalent to the convolution (denoted by ) of and . That is:

- If is a Hermitian function, then

- If both and are Hermitian, then .

- .

- Analogous to the convolution theorem, the cross-correlation satisfies

- where denotes the Fourier transform, and an again indicates the complex conjugate of , since . Coupled with fast Fourier transform algorithms, this property is often exploited for the efficient numerical computation of cross-correlations[9] (see circular cross-correlation).

- The cross-correlation is related to the spectral density (see Wiener–Khinchin theorem).

- The cross-correlation of a convolution of and with a function is the convolution of the cross-correlation of and with the kernel :

- .

Cross-correlation of random vectors

[edit]Definition

[edit]For random vectors and , each containing random elements whose expected value and variance exist, the cross-correlation matrix of and is defined by[10]: p.337 and has dimensions . Written component-wise:The random vectors and need not have the same dimension, and either might be a scalar value. Where is the expectation value.

Example

[edit]For example, if and are random vectors, then is a matrix whose -th entry is .

Definition for complex random vectors

[edit]If and are complex random vectors, each containing random variables whose expected value and variance exist, the cross-correlation matrix of and is defined bywhere denotes Hermitian transposition.

Cross-correlation of stochastic processes

[edit]In time series analysis and statistics, the cross-correlation of a pair of random process is the correlation between values of the processes at different times, as a function of the two times. Let be a pair of random processes, and be any point in time ( may be an integer for a discrete-time process or a real number for a continuous-time process). Then is the value (or realization) produced by a given run of the process at time .

Cross-correlation function

[edit]Suppose that the process has means and and variances and at time , for each . Then the definition of the cross-correlation between times and is[10]: p.392 where is the expected value operator. Note that this expression may be not defined.

Cross-covariance function

[edit]Subtracting the mean before multiplication yields the cross-covariance between times and :[10]: p.392 Note that this expression is not well-defined for all time series or processes, because the mean or variance may not exist.

Definition for wide-sense stationary stochastic process

[edit]Let represent a pair of stochastic processes that are jointly wide-sense stationary. Then the cross-covariance function and the cross-correlation function are given as follows.

Cross-correlation function

[edit]or equivalently

Cross-covariance function

[edit]or equivalently where and are the mean and standard deviation of the process , which are constant over time due to stationarity; and similarly for , respectively. indicates the expected value. That the cross-covariance and cross-correlation are independent of is precisely the additional information (beyond being individually wide-sense stationary) conveyed by the requirement that are jointly wide-sense stationary.

The cross-correlation of a pair of jointly wide sense stationary stochastic processes can be estimated by averaging the product of samples measured from one process and samples measured from the other (and its time shifts). The samples included in the average can be an arbitrary subset of all the samples in the signal (e.g., samples within a finite time window or a sub-sampling[which?] of one of the signals). For a large number of samples, the average converges to the true cross-correlation.

Normalization

[edit]It is common practice in some disciplines (e.g. statistics and time series analysis) to normalize the cross-correlation function to get a time-dependent Pearson correlation coefficient. However, in other disciplines (e.g. engineering) the normalization is usually dropped and the terms "cross-correlation" and "cross-covariance" are used interchangeably.

The definition of the normalized cross-correlation of a stochastic process isIf the function is well-defined, its value must lie in the range , with 1 indicating perfect correlation and −1 indicating perfect anti-correlation.

For jointly wide-sense stationary stochastic processes, the definition isThe normalization is important both because the interpretation of the autocorrelation as a correlation provides a scale-free measure of the strength of statistical dependence, and because the normalization has an effect on the statistical properties of the estimated autocorrelations.

Properties

[edit]Symmetry property

[edit]For jointly wide-sense stationary stochastic processes, the cross-correlation function has the following symmetry property:[11]: p.173 Respectively for jointly WSS processes:

Time delay analysis

[edit]Cross-correlations are useful for determining the time delay between two signals, e.g., for determining time delays for the propagation of acoustic signals across a microphone array.[12][13][clarification needed] After calculating the cross-correlation between the two signals, the maximum (or minimum if the signals are negatively correlated) of the cross-correlation function indicates the point in time where the signals are best aligned; i.e., the time delay between the two signals is determined by the argument of the maximum, or arg max of the cross-correlation, as inTerminology in image processing

Zero-normalized cross-correlation (ZNCC)

[edit]For image-processing applications in which the brightness of the image and template can vary due to lighting and exposure conditions, the images can be first normalized. This is typically done at every step by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. That is, the cross-correlation of a template with a subimage is

where is the number of pixels in and , is the average of and is standard deviation of .

In functional analysis terms, this can be thought of as the dot product of two normalized vectors. That is, ifandthen the above sum is equal towhere is the inner product and is the L² norm. Cauchy–Schwarz then implies that ZNCC has a range of .

Thus, if and are real matrices, their normalized cross-correlation equals the cosine of the angle between the unit vectors and , being thus if and only if equals multiplied by a positive scalar.

Normalized correlation is one of the methods used for template matching, a process used for finding instances of a pattern or object within an image. It is also the 2-dimensional version of Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient.

Normalized cross-correlation (NCC)

[edit]NCC is similar to ZNCC with the only difference of not subtracting the local mean value of intensities:

Nonlinear systems

[edit]Caution must be applied when using cross correlation function which assumes Gaussian variance for nonlinear systems. In certain circumstances, which depend on the properties of the input, cross correlation between the input and output of a system with nonlinear dynamics can be completely blind to certain nonlinear effects.[14] This problem arises because some quadratic moments can equal zero and this can incorrectly suggest that there is little "correlation" (in the sense of statistical dependence) between two signals, when in fact the two signals are strongly related by nonlinear dynamics.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bracewell, R. "Pentagram Notation for Cross Correlation." The Fourier Transform and Its Applications. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 46 and 243, 1965.

- ^ Papoulis, A. The Fourier Integral and Its Applications. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 244–245 and 252-253, 1962.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Cross-Correlation." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Cross-Correlation.html

- ^ Rabiner, L.R.; Schafer, R.W. (1978). Digital Processing of Speech Signals. Signal Processing Series. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0132136031.

- ^ Rabiner, Lawrence R.; Gold, Bernard (1975). Theory and Application of Digital Signal Processing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. pp. 401. ISBN 0139141014.

- ^ Wang, Chen (2019). Kernel learning for visual perception, Chapter 2.2.1 (Doctoral thesis). Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. pp. 17–18. doi:10.32657/10220/47835. hdl:10356/105527.

- ^ Wang, Chen; Zhang, Le; Yuan, Junsong; Xie, Lihua (2018). "Kernel Cross-Correlator". Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. The Thirty-second AAAI Conference On Artificial Intelligence. 32. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: 4179–4186. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11710. S2CID 3544911.

- ^ Campbell; Lo; MacKinlay (1996). The Econometrics of Financial Markets. NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691043019.

- ^ Kapinchev, Konstantin; Bradu, Adrian; Barnes, Frederick; Podoleanu, Adrian (2015). "GPU implementation of cross-correlation for image generation in real time". 2015 9th International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Systems (ICSPCS). pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICSPCS.2015.7391783. ISBN 978-1-4673-8118-5. S2CID 17108908.

- ^ a b c Gubner, John A. (2006). Probability and Random Processes for Electrical and Computer Engineers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86470-1.

- ^ Kun Il Park, Fundamentals of Probability and Stochastic Processes with Applications to Communications, Springer, 2018, 978-3-319-68074-3

- ^ Rhudy, Matthew; Brian Bucci; Jeffrey Vipperman; Jeffrey Allanach; Bruce Abraham (November 2009). Microphone Array Analysis Methods Using Cross-Correlations. Proceedings of 2009 ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress, Lake Buena Vista, FL. pp. 281–288. doi:10.1115/IMECE2009-10798. ISBN 978-0-7918-4388-8.

- ^ Rhudy, Matthew (November 2009). Real Time Implementation of a Military Impulse Classifier (MS thesis). University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Billings, S. A. (2013). Nonlinear System Identification: NARMAX Methods in the Time, Frequency, and Spatio-Temporal Domains. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-53556-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Tahmasebi, Pejman; Hezarkhani, Ardeshir; Sahimi, Muhammad (2012). "Multiple-point geostatistical modeling based on the cross-correlation functions". Computational Geosciences. 16 (3): 779–797. Bibcode:2012CmpGe..16..779T. doi:10.1007/s10596-012-9287-1. S2CID 62710397.

External links

[edit]Cross-correlation

View on Grokipediaxcorr function, facilitate its computation for practical research across disciplines.[2]

![{\displaystyle [t_{0},t_{0}+T]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/42861c0e088bf0086b4c7ca5bbd5c05f5b625955)

![{\displaystyle (f\star g)[n]\ \triangleq \sum _{m=-\infty }^{\infty }{\overline {f[m]}}g[m+n]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ae7436d14af449d42157c82e157f60fa895617f)

![{\displaystyle (f\star g)[n]\ \triangleq \sum _{m=-\infty }^{\infty }{\overline {f[m-n]}}g[m]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1e2f1b1ff6554ad1d13c74259ba020f6073de03e)

![{\displaystyle (f\star g)[n]\ \triangleq \sum _{m=0}^{N-1}{\overline {f[m]}}g[(m+n)_{{\text{mod}}~N}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4fd4e6fb030aa161b54e49a378264cd3f2a1a469)

![{\displaystyle (f\star g)[n]\ \triangleq \sum _{m=0}^{N-1}{\overline {f[(m-n)_{{\text{mod}}~N}]}}g[m]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a7bbedcb034c4c3c58d19f479d622d01b044387b)

![{\displaystyle (f\star g)[n]\ \triangleq \sum _{m=0}^{N-1}{\overline {f[m]}}K_{g}[(m+n)_{{\text{mod}}~N}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/061dbe28fd5a202b73d4c3b67b711c90acb794d7)

![{\displaystyle K_{g}=[k(g,T_{0}(g)),k(g,T_{1}(g)),\dots ,k(g,T_{N-1}(g))]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7840b890e6b1c966eda471075b71ea4872ebbdc7)

=[{\overline {f(-t)}}*g(t)](t).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/42bba62c30eba9816006d62139738eada9042b6b)

=[{\overline {g(t)}}\star {\overline {f(t)}}](-t).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/beaed12f1c40290fe0d5f85074565b67101b2b06)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {R} _{\mathbf {X} \mathbf {Y} }\triangleq \ \operatorname {E} \left[\mathbf {X} \mathbf {Y} \right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/52e05c6dc5d69cbfb2da8703d27f6e1b0b274374)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {R} _{\mathbf {X} \mathbf {Y} }={\begin{bmatrix}\operatorname {E} [X_{1}Y_{1}]&\operatorname {E} [X_{1}Y_{2}]&\cdots &\operatorname {E} [X_{1}Y_{n}]\\\\\operatorname {E} [X_{2}Y_{1}]&\operatorname {E} [X_{2}Y_{2}]&\cdots &\operatorname {E} [X_{2}Y_{n}]\\\\\vdots &\vdots &\ddots &\vdots \\\\\operatorname {E} [X_{m}Y_{1}]&\operatorname {E} [X_{m}Y_{2}]&\cdots &\operatorname {E} [X_{m}Y_{n}]\end{bmatrix}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/742e24fd35f55178322a662313679ef3dfdea0a3)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [X_{i}Y_{j}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e511d6ea021c2d4b0579f621faec897ec52a1999)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {R} _{\mathbf {Z} \mathbf {W} }\triangleq \ \operatorname {E} [\mathbf {Z} \mathbf {W} ^{\rm {H}}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b96a25804b6f71adb2dd4366a18cc65e96553d88)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {R} _{XY}(t_{1},t_{2})\triangleq \ \operatorname {E} \left[X_{t_{1}}{\overline {Y_{t_{2}}}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1e6c49fd6a80159006028664b00760b503b0f561)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {K} _{XY}(t_{1},t_{2})\triangleq \ \operatorname {E} \left[\left(X_{t_{1}}-\mu _{X}(t_{1})\right){\overline {(Y_{t_{2}}-\mu _{Y}(t_{2}))}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b202f0ccc8691a4d40dd8d4c98fa0f53388716dc)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {R} _{XY}(\tau )\triangleq \ \operatorname {E} \left[X_{t}{\overline {Y_{t+\tau }}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5b171fee784670f0dac44d562d19e13bb97888e3)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {R} _{XY}(\tau )=\operatorname {E} \left[X_{t-\tau }{\overline {Y_{t}}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/815c784f50990cb9c2e3ec33e182afa5a04960fb)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {K} _{XY}(\tau )\triangleq \ \operatorname {E} \left[\left(X_{t}-\mu _{X}\right){\overline {\left(Y_{t+\tau }-\mu _{Y}\right)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4dae097558058459f1aa7b0738e4e62de9e8c23d)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {K} _{XY}(\tau )=\operatorname {E} \left[\left(X_{t-\tau }-\mu _{X}\right){\overline {\left(Y_{t}-\mu _{Y}\right)}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cc501844193bdcd2665a4a613fd9fe3c8a260be3)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {E} [\ ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/780439555973c827b4819f1ce09717a3f334fd27)

![{\displaystyle \rho _{XX}(t_{1},t_{2})={\frac {\operatorname {K} _{XX}(t_{1},t_{2})}{\sigma _{X}(t_{1})\sigma _{X}(t_{2})}}={\frac {\operatorname {E} \left[\left(X_{t_{1}}-\mu _{t_{1}}\right){\overline {\left(X_{t_{2}}-\mu _{t_{2}}\right)}}\right]}{\sigma _{X}(t_{1})\sigma _{X}(t_{2})}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/62ffe542d8c069c97cbf975511108207b72c8cd4)

![{\displaystyle [-1,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/51e3b7f14a6f70e614728c583409a0b9a8b9de01)

![{\displaystyle \rho _{XY}(\tau )={\frac {\operatorname {K} _{XY}(\tau )}{\sigma _{X}\sigma _{Y}}}={\frac {\operatorname {E} \left[\left(X_{t}-\mu _{X}\right){\overline {\left(Y_{t+\tau }-\mu _{Y}\right)}}\right]}{\sigma _{X}\sigma _{Y}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9db7fd85b86dc22dc1fc00e4be38faeecc96c42b)