Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dirac delta function

View on Wikipedia

| Differential equations |

|---|

| Scope |

| Classification |

| Solution |

| People |

In mathematical analysis, the Dirac delta function (or δ distribution), also known as the unit impulse,[1] is a generalized function on the real numbers, whose value is zero everywhere except at zero, and whose integral over the entire real line is equal to one.[2][3][4] Thus it can be represented heuristically as

such that

Since there is no function having this property, modelling the delta "function" rigorously involves the use of limits or, as is common in mathematics, measure theory and the theory of distributions.

The delta function was introduced by physicist Paul Dirac, and has since been applied routinely in physics and engineering to model point masses and instantaneous impulses. It is called the delta function because it is a continuous analogue of the Kronecker delta function, which is usually defined on a discrete domain and takes values 0 and 1. The mathematical rigor of the delta function was disputed until Laurent Schwartz developed the theory of distributions, where it is defined as a linear form acting on functions.

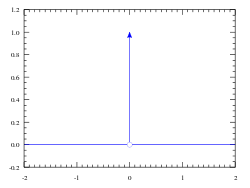

Motivation and overview

[edit]The graph of the Dirac delta is usually thought of as following the whole x-axis and the positive y-axis.[5] The Dirac delta is used to model a tall narrow spike function (an impulse), and other similar abstractions such as a point charge or point mass.[6][7] For example, to calculate the dynamics of a billiard ball being struck, one can approximate the force of the impact by a Dirac delta. In doing so, one can simplify the equations and calculate the motion of the ball by only considering the total impulse of the collision, without a detailed model of all of the elastic energy transfer at subatomic levels (for instance).

To be specific, suppose that a billiard ball is at rest. At time it is struck by another ball, imparting it with a momentum P, with units kg⋅m⋅s−1. The exchange of momentum is not actually instantaneous, being mediated by elastic processes at the molecular and subatomic level, but for practical purposes it is convenient to consider that energy transfer as effectively instantaneous. The force therefore is P δ(t); the units of δ(t) are s−1.

To model this situation more rigorously, suppose that the force instead is uniformly distributed over a small time interval . That is,

Then the momentum at any time t is found by integration:

Now, the model situation of an instantaneous transfer of momentum requires taking the limit as Δt → 0, giving a result everywhere except at 0:

Here the functions are thought of as useful approximations to the idea of instantaneous transfer of momentum.

The delta function allows us to construct an idealized limit of these approximations. Unfortunately, the actual limit of the functions (in the sense of pointwise convergence) is zero everywhere but a single point, where it is infinite. To make proper sense of the Dirac delta, we should instead insist that the property

which holds for all , should continue to hold in the limit. So, in the equation , it is understood that the limit is always taken outside the integral.

In applied mathematics, as we have done here, the delta function is often manipulated as a kind of limit (a weak limit) of a sequence of functions, each member of which has a tall spike at the origin: for example, a sequence of Gaussian distributions centered at the origin with variance tending to zero. (However, even in some applications, highly oscillatory functions are used as approximations to the delta function, see below.)

The Dirac delta, given the desired properties outlined above, cannot be a function with domain and range in real numbers.[4] For example, the objects f(x) = δ(x) and g(x) = 0 are equal everywhere except at x = 0 yet have integrals that are different. According to Lebesgue integration theory, if f and g are functions such that f = g almost everywhere, then f is integrable if and only if g is integrable and the integrals of f and g are identical.[8] A rigorous approach to regarding the Dirac delta function as a mathematical object in its own right uses measure theory or the theory of distributions.[9]

History

[edit]In physics, the Dirac delta function was popularized by Paul Dirac in this book The Principles of Quantum Mechanics published in 1930.[3] However, Oliver Heaviside, 35 years before Dirac, described an impulsive function called the Heaviside step function for purposes and with properties analogous to Dirac's work. Even earlier several mathematicians and physicists used limits of sharply peaked functions in derivations.[10] An infinitesimal formula for an infinitely tall, unit impulse delta function (infinitesimal version of Cauchy distribution) explicitly appears in an 1827 text of Augustin-Louis Cauchy.[11] Siméon Denis Poisson considered the issue in connection with the study of wave propagation as did Gustav Kirchhoff somewhat later. Kirchhoff and Hermann von Helmholtz also introduced the unit impulse as a limit of Gaussians, which also corresponded to Lord Kelvin's notion of a point heat source.[12] The Dirac delta function as such was introduced by Paul Dirac in his 1927 paper The Physical Interpretation of the Quantum Dynamics.[13] He called it the "delta function" since he used it as a continuum analogue of the discrete Kronecker delta.[3]

Mathematicians refer to the same concept as a distribution rather than a function.[14] Joseph Fourier presented what is now called the Fourier integral theorem in his treatise Théorie analytique de la chaleur in the form:[15]

which is tantamount to the introduction of the δ-function in the form:[16]

Later, Augustin Cauchy expressed the theorem using exponentials:[17][18]

Cauchy pointed out that in some circumstances the order of integration is significant in this result (contrast Fubini's theorem).[19][20]

As justified using the theory of distributions, the Cauchy equation can be rearranged to resemble Fourier's original formulation and expose the δ-function as

where the δ-function is expressed as

A rigorous interpretation of the exponential form and the various limitations upon the function f necessary for its application extended over several centuries. The problems with a classical interpretation are explained as follows:[21]

- The greatest drawback of the classical Fourier transformation is a rather narrow class of functions (originals) for which it can be effectively computed. Namely, it is necessary that these functions decrease sufficiently rapidly to zero (in the neighborhood of infinity) to ensure the existence of the Fourier integral. For example, the Fourier transform of such simple functions as polynomials does not exist in the classical sense. The extension of the classical Fourier transformation to distributions considerably enlarged the class of functions that could be transformed and this removed many obstacles.

Further developments included generalization of the Fourier integral, "beginning with Plancherel's pathbreaking L2-theory (1910), continuing with Wiener's and Bochner's works (around 1930) and culminating with the amalgamation into L. Schwartz's theory of distributions (1945) ...",[22] and leading to the formal development of the Dirac delta function.

Definitions

[edit]The Dirac delta function can be loosely thought of as a function on the real line which is zero everywhere except at the origin, where it is infinite,

and which is also constrained to satisfy the identity[23]

This is merely a heuristic characterization. The Dirac delta is not a function in the traditional sense as no extended real number valued function defined on the real numbers has these properties.[24]

As a measure

[edit]One way to rigorously capture the notion of the Dirac delta function is to define a measure, called Dirac measure, which accepts a subset A of the real line R as an argument, and returns δ(A) = 1 if 0 ∈ A, and δ(A) = 0 otherwise.[25] If the delta function is conceptualized as modeling an idealized point mass at 0, then δ(A) represents the mass contained in the set A. One may then define the integral against δ as the integral of a function against this mass distribution. Formally, the Lebesgue integral provides the necessary analytic device. The Lebesgue integral with respect to the measure δ satisfies

for all continuous compactly supported functions f. The measure δ is not absolutely continuous with respect to the Lebesgue measure—in fact, it is a singular measure. Consequently, the delta measure has no Radon–Nikodym derivative (with respect to Lebesgue measure)—no true function for which the property

holds.[26] As a result, the latter notation is a convenient abuse of notation, and not a standard (Riemann or Lebesgue) integral.[27]

As a probability measure on R, the delta measure is characterized by its cumulative distribution function, which is the unit step function.[28]

This means that H(x) is the integral of the cumulative indicator function 1(−∞, x] with respect to the measure δ; to wit,

the latter being the measure of this interval. Thus in particular the integration of the delta function against a continuous function can be properly understood as a Riemann–Stieltjes integral:[29]

All higher moments of δ are zero. In particular, characteristic function and moment generating function are both equal to one.[30]

As a distribution

[edit]In the theory of distributions, a generalized function is considered not a function in itself but only through how it affects other functions when "integrated" against them.[31] In keeping with this philosophy, to define the delta function properly, it is enough to say what the "integral" of the delta function is against a sufficiently "good" test function φ.[4] If the delta function is already understood as a measure, then the Lebesgue integral of a test function against that measure supplies the necessary integral.[32]

A typical space of test functions consists of all smooth functions on R with compact support that have as many derivatives as required. As a distribution, the Dirac delta is a linear functional on the space of test functions and is defined by[33]

| 1 |

for every test function φ.

For δ to be properly a distribution, it must be continuous in a suitable topology on the space of test functions. In general, for a linear functional S on the space of test functions to define a distribution, it is necessary and sufficient that, for every positive integer N there is an integer MN and a constant CN such that for every test function φ, one has the inequality[34]

where sup represents the supremum. With the δ distribution, one has such an inequality (with CN = 1) with MN = 0 for all N. Thus δ is a distribution of order zero. It is, furthermore, a distribution with compact support (the support being {0}).

The delta distribution can also be defined in several equivalent ways. For instance, it is the distributional derivative of the Heaviside step function. This means that for every test function φ, one has

Intuitively, if integration by parts were permitted, then the latter integral should simplify to

and indeed, a form of integration by parts is permitted for the Stieltjes integral, and in that case, one does have

In the context of measure theory, the Dirac measure gives rise to distribution by integration. Conversely, equation (1) defines a Daniell integral on the space of all compactly supported continuous functions φ which, by the Riesz representation theorem, can be represented as the Lebesgue integral of φ with respect to some Radon measure.[35]}

Generally, when the term Dirac delta function is used, it is in the sense of distributions rather than measures, the Dirac measure being among several terms for the corresponding notion in measure theory. Some sources may also use the term Dirac delta distribution.

Generalizations

[edit]The delta function can be defined in n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn as the measure such that

for every compactly supported continuous function f. As a measure, the n-dimensional delta function is the product measure of the 1-dimensional delta functions in each variable separately. Thus, formally, with x = (x1, x2, ..., xn), one has[36]

| 2 |

The delta function can also be defined in the sense of distributions exactly as above in the one-dimensional case.[37] However, despite widespread use in engineering contexts, (2) should be manipulated with care, since the product of distributions can only be defined under quite narrow circumstances.[38][39]

The notion of a Dirac measure makes sense on any set.[40] Thus if X is a set, x0 ∈ X is a marked point, and Σ is any sigma algebra of subsets of X, then the measure defined on sets A ∈ Σ by

is the delta measure or unit mass concentrated at x0.

Another common generalization of the delta function is to a differentiable manifold where most of its properties as a distribution can also be exploited because of the differentiable structure. The delta function on a manifold M centered at the point x0 ∈ M is defined as the following distribution:

| 3 |

for all compactly supported smooth real-valued functions φ on M.[41] A common special case of this construction is a case in which M is an open set in the Euclidean space Rn.

On a locally compact Hausdorff space X, the Dirac delta measure concentrated at a point x is the Radon measure associated with the Daniell integral (3) on compactly supported continuous functions φ.[42] At this level of generality, calculus as such is no longer possible, however a variety of techniques from abstract analysis are available. For instance, the mapping is a continuous embedding of X into the space of finite Radon measures on X, equipped with its vague topology. Moreover, the convex hull of the image of X under this embedding is dense in the space of probability measures on X.[43]

Properties

[edit]Scaling and symmetry

[edit]The delta function satisfies the following scaling property for a non-zero scalar α:[3][44]

and so

| 4 |

Scaling property proof: where a change of variable x′ = αx is used. If α is negative, i.e., α = −|a|, then Thus, .

In particular, the delta function is an even distribution (symmetry), in the sense that

which is homogeneous of degree −1.

Algebraic properties

[edit]The distributional product of δ with x is equal to zero:

More generally, for all positive integers .

Conversely, if xf(x) = xg(x), where f and g are distributions, then

for some constant c.[45]

Translation

[edit]The integral of any function multiplied by the time-delayed Dirac delta is

This is sometimes referred to as the sifting property[46] or the sampling property.[47] The delta function is said to "sift out" the value of f(t) at t = T.[48]

It follows that the effect of convolving a function f(t) with the time-delayed Dirac delta is to time-delay f(t) by the same amount:[49]

The sifting property holds under the precise condition that f be a tempered distribution (see the discussion of the Fourier transform below). As a special case, for instance, we have the identity (understood in the distribution sense)

Composition with a function

[edit]More generally, the delta distribution may be composed with a smooth function g(x) in such a way that the familiar change of variables formula holds (where ), that

provided that g is a continuously differentiable function with g′ nowhere zero.[50] That is, there is a unique way to assign meaning to the distribution so that this identity holds for all compactly supported test functions f. Therefore, the domain must be broken up to exclude the g′ = 0 point. This distribution satisfies δ(g(x)) = 0 if g is nowhere zero, and otherwise if g has a real root at x0, then

It is natural therefore to define the composition δ(g(x)) for continuously differentiable functions g by

where the sum extends over all roots of g(x), which are assumed to be simple. Thus, for example

In the integral form, the generalized scaling property may be written as

Indefinite integral

[edit]For a constant and a "well-behaved" arbitrary real-valued function y(x), where H(x) is the Heaviside step function and c is an integration constant.

Properties in n dimensions

[edit]The delta distribution in an n-dimensional space satisfies the following scaling property instead, so that δ is a homogeneous distribution of degree −n.

Under any reflection or rotation ρ, the delta function is invariant,

As in the one-variable case, it is possible to define the composition of δ with a bi-Lipschitz function[51] g: Rn → Rn uniquely so that the following holds for all compactly supported functions f.

Using the coarea formula from geometric measure theory, one can also define the composition of the delta function with a submersion from one Euclidean space to another one of different dimension; the result is a type of current. In the special case of a continuously differentiable function g : Rn → R such that the gradient of g is nowhere zero, the following identity holds[52] where the integral on the right is over g−1(0), the (n − 1)-dimensional surface defined by g(x) = 0 with respect to the Minkowski content measure. This is known as a simple layer integral.

More generally, if S is a smooth hypersurface of Rn, then we can associate to S the distribution that integrates any compactly supported smooth function g over S:

where σ is the hypersurface measure associated to S. This generalization is associated with the potential theory of simple layer potentials on S. If D is a domain in Rn with smooth boundary S, then δS is equal to the normal derivative of the indicator function of D in the distribution sense,

where n is the outward normal.[53][54]

In three dimensions, the delta function is represented in spherical coordinates by:

Derivatives

[edit]The derivative of the Dirac delta distribution, denoted δ′ and also called the Dirac delta prime or Dirac delta derivative, is defined on compactly supported smooth test functions φ by[55]

The first equality here is a kind of integration by parts, for if δ were a true function then

By mathematical induction, the k-th derivative of δ is defined similarly as the distribution given on test functions by

In particular, δ is an infinitely differentiable distribution.

The first derivative of the delta function is the distributional limit of the difference quotients:[56]

More properly, one has where τh is the translation operator, defined on functions by τhφ(x) = φ(x + h), and on a distribution S by

In the theory of electromagnetism, the first derivative of the delta function represents a point magnetic dipole situated at the origin. Accordingly, it is referred to as a dipole or the doublet function.[57]

The derivative of the delta function satisfies a number of basic properties, including:[58] which can be shown by applying a test function and integrating by parts.

The latter of these properties can also be demonstrated by applying distributional derivative definition, Leibniz 's theorem and linearity of inner product:[59][better source needed]

Furthermore, the convolution of δ′ with a compactly-supported, smooth function f is

which follows from the properties of the distributional derivative of a convolution.

Higher dimensions

[edit]More generally, on an open set U in the n-dimensional Euclidean space , the Dirac delta distribution centered at a point a ∈ U is defined by[60] for all , the space of all smooth functions with compact support on U. If is any multi-index with and denotes the associated mixed partial derivative operator, then the α-th derivative ∂αδa of δa is given by[60]

That is, the α-th derivative of δa is the distribution whose value on any test function φ is the α-th derivative of φ at a (with the appropriate positive or negative sign).

The first partial derivatives of the delta function are thought of as double layers along the coordinate planes. More generally, the normal derivative of a simple layer supported on a surface is a double layer supported on that surface and represents a laminar magnetic monopole. Higher derivatives of the delta function are known in physics as multipoles.[61]

Higher derivatives enter into mathematics naturally as the building blocks for the complete structure of distributions with point support. If S is any distribution on U supported on the set {a} consisting of a single point, then there is an integer m and coefficients cα such that[60][62]

Representations

[edit]The delta function can be viewed as the limit of a sequence of functions

This limit is meant in a weak sense: either that

| 5 |

for all continuous functions f having compact support, or that this limit holds for all smooth functions f with compact support. The former is convergence in the vague topology of measures, and the latter is convergence in the sense of distributions.

Approximations to the identity

[edit]An approximate delta function ηε can be constructed in the following manner. Let η be an absolutely integrable function on R of total integral 1, and define

In n dimensions, one uses instead the scaling

Then a simple change of variables shows that ηε also has integral 1. One may show that (5) holds for all continuous compactly supported functions f,[63] and so ηε converges weakly to δ in the sense of measures.

The ηε constructed in this way are known as an approximation to the identity.[64] This terminology is because the space L1(R) of absolutely integrable functions is closed under the operation of convolution of functions: f ∗ g ∈ L1(R) whenever f and g are in L1(R). However, there is no identity in L1(R) for the convolution product: no element h such that f ∗ h = f for all f. Nevertheless, the sequence ηε does approximate such an identity in the sense that

This limit holds in the sense of mean convergence (convergence in L1). Further conditions on the ηε, for instance that it be a mollifier associated to a compactly supported function,[65] are needed to ensure pointwise convergence almost everywhere.

If the initial η = η1 is itself smooth and compactly supported then the sequence is called a mollifier. The standard mollifier is obtained by choosing η to be a suitably normalized bump function, for instance

( ensuring that the total integral is 1).

In some situations such as numerical analysis, a piecewise linear approximation to the identity is desirable. This can be obtained by taking η1 to be a hat function. With this choice of η1, one has

which are all continuous and compactly supported, although not smooth and so not a mollifier.

Probabilistic considerations

[edit]In the context of probability theory, it is natural to impose the additional condition that the initial η1 in an approximation to the identity should be positive, as such a function then represents a probability distribution. Convolution with a probability distribution is sometimes favorable because it does not result in overshoot or undershoot, as the output is a convex combination of the input values, and thus falls between the maximum and minimum of the input function. Taking η1 to be any probability distribution at all, and letting ηε(x) = η1(x/ε)/ε as above will give rise to an approximation to the identity. In general this converges more rapidly to a delta function if, in addition, η has mean 0 and has small higher moments. For instance, if η1 is the uniform distribution on , also known as the rectangular function, then:[66]

Another example is with the Wigner semicircle distribution

This is continuous and compactly supported, but not a mollifier because it is not smooth.

Semigroups

[edit]Approximations to the delta functions often arise as convolution semigroups.[67] This amounts to the further constraint that the convolution of ηε with ηδ must satisfy

for all ε, δ > 0. Convolution semigroups in L1 that approximate the delta function are always an approximation to the identity in the above sense, however the semigroup condition is quite a strong restriction.

In practice, semigroups approximating the delta function arise as fundamental solutions or Green's functions to physically motivated elliptic or parabolic partial differential equations. In the context of applied mathematics, semigroups arise as the output of a linear time-invariant system. Abstractly, if A is a linear operator acting on functions of x, then a convolution semigroup arises by solving the initial value problem

in which the limit is as usual understood in the weak sense. Setting ηε(x) = η(ε, x) gives the associated approximate delta function.

Some examples of physically important convolution semigroups arising from such a fundamental solution include the following.

The heat kernel

[edit]The heat kernel, defined by[68]

represents the temperature in an infinite wire at time t > 0, if a unit of heat energy is stored at the origin of the wire at time t = 0. This semigroup evolves according to the one-dimensional heat equation:

In probability theory, ηε(x) is a normal distribution of variance ε and mean 0. It represents the probability density at time t = ε of the position of a particle starting at the origin following a standard Brownian motion. In this context, the semigroup condition is then an expression of the Markov property of Brownian motion.

In higher-dimensional Euclidean space Rn, the heat kernel is and has the same physical interpretation, mutatis mutandis. It also represents an approximation to the delta function in the sense that ηε → δ in the distribution sense as ε → 0.

The Poisson kernel

[edit]The Poisson kernel

is the fundamental solution of the Laplace equation in the upper half-plane.[69] It represents the electrostatic potential in a semi-infinite plate whose potential along the edge is held at fixed at the delta function. The Poisson kernel is also closely related to the Cauchy distribution and Epanechnikov and Gaussian kernel functions.[70] This semigroup evolves according to the equation

where the operator is rigorously defined as the Fourier multiplier

Oscillatory integrals

[edit]In areas of physics such as wave propagation and wave mechanics, the equations involved are hyperbolic and so may have more singular solutions. As a result, the approximate delta functions that arise as fundamental solutions of the associated Cauchy problems are generally oscillatory integrals. An example, which comes from a solution of the Euler–Tricomi equation of transonic gas dynamics,[71] is the rescaled Airy function

Although using the Fourier transform, it is easy to see that this generates a semigroup in some sense—it is not absolutely integrable and so cannot define a semigroup in the above strong sense. Many approximate delta functions constructed as oscillatory integrals only converge in the sense of distributions (an example is the Dirichlet kernel below), rather than in the sense of measures.

Another example is the Cauchy problem for the wave equation in R1+1:[72]

The solution u represents the displacement from equilibrium of an infinite elastic string, with an initial disturbance at the origin.

Other approximations to the identity of this kind include the sinc function (used widely in electronics and telecommunications)

and the Bessel function

Plane wave decomposition

[edit]One approach to the study of a linear partial differential equation

where L is a differential operator on Rn, is to seek first a fundamental solution, which is a solution of the equation

When L is particularly simple, this problem can often be resolved using the Fourier transform directly (as in the case of the Poisson kernel and heat kernel already mentioned). For more complicated operators, it is sometimes easier first to consider an equation of the form

where h is a plane wave function, meaning that it has the form

for some vector ξ. Such an equation can be resolved (if the coefficients of L are analytic functions) by the Cauchy–Kovalevskaya theorem or (if the coefficients of L are constant) by quadrature. So, if the delta function can be decomposed into plane waves, then one can in principle solve linear partial differential equations.

Such a decomposition of the delta function into plane waves was part of a general technique first introduced essentially by Johann Radon, and then developed in this form by Fritz John (1955).[73] Choose k so that n + k is an even integer, and for a real number s, put

Then δ is obtained by applying a power of the Laplacian to the integral with respect to the unit sphere measure dω of g(x · ξ) for ξ in the unit sphere Sn−1:

The Laplacian here is interpreted as a weak derivative, so that this equation is taken to mean that, for any test function φ,

The result follows from the formula for the Newtonian potential (the fundamental solution of Poisson's equation). This is essentially a form of the inversion formula for the Radon transform because it recovers the value of φ(x) from its integrals over hyperplanes.[74] For instance, if n is odd and k = 1, then the integral on the right hand side is

where Rφ(ξ, p) is the Radon transform of φ:

An alternative equivalent expression of the plane wave decomposition is:[75]

Fourier transform

[edit]The delta function is a tempered distribution, and therefore it has a well-defined Fourier transform. Formally, one finds[76]

Properly speaking, the Fourier transform of a distribution is defined by imposing self-adjointness of the Fourier transform under the duality pairing of tempered distributions with Schwartz functions. Thus is defined as the unique tempered distribution satisfying

for all Schwartz functions φ. And indeed it follows from this that

As a result of this identity, the convolution of the delta function with any other tempered distribution S is simply S:

That is to say that δ is an identity element for the convolution on tempered distributions, and in fact, the space of compactly supported distributions under convolution is an associative algebra with identity the delta function. This property is fundamental in signal processing, as convolution with a tempered distribution is a linear time-invariant system, and applying the linear time-invariant system measures its impulse response. The impulse response can be computed to any desired degree of accuracy by choosing a suitable approximation for δ, and once it is known, it characterizes the system completely. See LTI system theory § Impulse response and convolution.

The inverse Fourier transform of the tempered distribution f(ξ) = 1 is the delta function. Formally, this is expressed as and more rigorously, it follows since for all Schwartz functions f.

In these terms, the delta function provides a suggestive statement of the orthogonality property of the Fourier kernel on R. Formally, one has

This is, of course, shorthand for the assertion that the Fourier transform of the tempered distribution is which again follows by imposing self-adjointness of the Fourier transform.

By analytic continuation of the Fourier transform, the Laplace transform of the delta function is found to be[77]

Fourier kernels

[edit]In the study of Fourier series, a major question consists of determining whether and in what sense the Fourier series associated with a periodic function converges to the function. The n-th partial sum of the Fourier series of a function f of period 2π is defined by convolution (on the interval [−π,π]) with the Dirichlet kernel: Thus, where A fundamental result of elementary Fourier series states that the Dirichlet kernel restricted to the interval [−π,π] tends to a multiple of the delta function as N → ∞. This is interpreted in the distribution sense, that for every compactly supported smooth function f. Thus, formally one has on the interval [−π,π].

Despite this, the result does not hold for all compactly supported continuous functions: that is DN does not converge weakly in the sense of measures. The lack of convergence of the Fourier series has led to the introduction of a variety of summability methods to produce convergence. The method of Cesàro summation leads to the Fejér kernel[78]

The Fejér kernels tend to the delta function in a stronger sense that[79]

for every compactly supported continuous function f. The implication is that the Fourier series of any continuous function is Cesàro summable to the value of the function at every point.

Hilbert space theory

[edit]The Dirac delta distribution is a densely defined unbounded linear functional on the Hilbert space L2 of square-integrable functions.[80] Indeed, smooth compactly supported functions are dense in L2, and the action of the delta distribution on such functions is well-defined. In many applications, it is possible to identify subspaces of L2 and to give a stronger topology on which the delta function defines a bounded linear functional.

Sobolev spaces

[edit]The Sobolev embedding theorem for Sobolev spaces on the real line R implies that any square-integrable function f such that

is automatically continuous, and satisfies in particular

Thus δ is a bounded linear functional on the Sobolev space H1.[81] Equivalently δ is an element of the continuous dual space H−1 of H1. More generally, in n dimensions, one has δ ∈ H−s(Rn) provided s > n/2.

Spaces of holomorphic functions

[edit]In complex analysis, the delta function enters via Cauchy's integral formula, which asserts that if D is a domain in the complex plane with smooth boundary, then

for all holomorphic functions f in D that are continuous on the closure of D. As a result, the delta function δz is represented in this class of holomorphic functions by the Cauchy integral:

Moreover, let H2(∂D) be the Hardy space consisting of the closure in L2(∂D) of all holomorphic functions in D continuous up to the boundary of D. Then functions in H2(∂D) uniquely extend to holomorphic functions in D, and the Cauchy integral formula continues to hold. In particular for z ∈ D, the delta function δz is a continuous linear functional on H2(∂D). This is a special case of the situation in several complex variables in which, for smooth domains D, the Szegő kernel plays the role of the Cauchy integral.[82]

Another representation of the delta function in a space of holomorphic functions is on the space of square-integrable holomorphic functions in an open set . This is a closed subspace of , and therefore is a Hilbert space. On the other hand, the functional that evaluates a holomorphic function in at a point of is a continuous functional, and so by the Riesz representation theorem, is represented by integration against a kernel , the Bergman kernel.[83] This kernel is the analog of the delta function in this Hilbert space. A Hilbert space having such a kernel is called a reproducing kernel Hilbert space. In the special case of the unit disc, one has

Resolutions of the identity

[edit]Given a complete orthonormal basis set of functions {φn} in a separable Hilbert space, for example, the normalized eigenvectors of a compact self-adjoint operator, any vector f can be expressed as The coefficients {αn} are found as which may be represented by the notation: a form of the bra–ket notation of Dirac.[84] Adopting this notation, the expansion of f takes the dyadic form:[85]

Letting I denote the identity operator on the Hilbert space, the expression

is called a resolution of the identity. When the Hilbert space is the space L2(D) of square-integrable functions on a domain D, the quantity:

is an integral operator, and the expression for f can be rewritten

The right-hand side converges to f in the L2 sense. It need not hold in a pointwise sense, even when f is a continuous function. Nevertheless, it is common to abuse notation and write

resulting in the representation of the delta function:[86]

With a suitable rigged Hilbert space (Φ, L2(D), Φ*) where Φ ⊂ L2(D) contains all compactly supported smooth functions, this summation may converge in Φ*, depending on the properties of the basis φn. In most cases of practical interest, the orthonormal basis comes from an integral or differential operator (e.g. the heat kernel), in which case the series converges in the distribution sense.[87]

Infinitesimal delta functions

[edit]Cauchy used an infinitesimal α to write down a unit impulse, infinitely tall and narrow Dirac-type delta function δα satisfying in a number of articles in 1827.[88] Cauchy defined an infinitesimal in Cours d'Analyse (1827) in terms of a sequence tending to zero. Namely, such a null sequence becomes an infinitesimal in Cauchy's and Lazare Carnot's terminology.

Non-standard analysis allows one to rigorously treat infinitesimals. The article by Yamashita (2007) contains a bibliography on modern Dirac delta functions in the context of an infinitesimal-enriched continuum provided by the hyperreals. Here the Dirac delta can be given by an actual function, having the property that for every real function F one has as anticipated by Fourier and Cauchy.

Dirac comb

[edit]

A so-called uniform "pulse train" of Dirac delta measures, which is known as a Dirac comb, or as the Sha distribution, creates a sampling function, often used in digital signal processing (DSP) and discrete time signal analysis. The Dirac comb is given as the infinite sum, whose limit is understood in the distribution sense,

which is a sequence of point masses at each of the integers.

Up to an overall normalizing constant, the Dirac comb is equal to its own Fourier transform. This is significant because if f is any Schwartz function, then the periodization of f is given by the convolution In particular, is precisely the Poisson summation formula.[89][90] More generally, this formula remains to be true if f is a tempered distribution of rapid descent or, equivalently, if is a slowly growing, ordinary function within the space of tempered distributions.

Sokhotski–Plemelj theorem

[edit]The Sokhotski–Plemelj theorem, important in quantum mechanics, relates the delta function to the distribution p.v. 1/x, the Cauchy principal value of the function 1/x, defined by

Sokhotsky's formula states that[91]

Here the limit is understood in the distribution sense, that for all compactly supported smooth functions f,

Relationship to the Kronecker delta

[edit]The Kronecker delta δij is the quantity defined by

for all integers i, j. This function then satisfies the following analog of the sifting property: if ai (for i in the set of all integers) is any doubly infinite sequence, then

Similarly, for any real or complex valued continuous function f on R, the Dirac delta satisfies the sifting property

This exhibits the Kronecker delta function as a discrete analog of the Dirac delta function.[92]

Applications

[edit]Probability theory

[edit]In probability theory and statistics, the Dirac delta function is often used to represent a discrete distribution, or a partially discrete, partially continuous distribution, using a probability density function (which is normally used to represent absolutely continuous distributions). For example, the probability density function f(x) of a discrete distribution consisting of points x = {x1, ..., xn}, with corresponding probabilities p1, ..., pn, can be written as[93]

As another example, consider a distribution in which 6/10 of the time returns a standard normal distribution, and 4/10 of the time returns exactly the value 3.5 (i.e. a partly continuous, partly discrete mixture distribution). The density function of this distribution can be written as

The delta function is also used to represent the resulting probability density function of a random variable that is transformed by continuously differentiable function. If Y = g(X) is a continuous differentiable function, then the density of Y can be written as

The delta function is also used in a completely different way to represent the local time of a diffusion process (like Brownian motion).[94] The local time of a stochastic process B(t) is given by and represents the amount of time that the process spends at the point x in the range of the process. More precisely, in one dimension this integral can be written where is the indicator function of the interval

Quantum mechanics

[edit]The delta function is expedient in quantum mechanics. The wave function of a particle gives the probability amplitude of finding a particle within a given region of space. Wave functions are assumed to be elements of the Hilbert space L2 of square-integrable functions, and the total probability of finding a particle within a given interval is the integral of the magnitude of the wave function squared over the interval. A set {|φn⟩} of wave functions is orthonormal if

where δnm is the Kronecker delta. A set of orthonormal wave functions is complete in the space of square-integrable functions if any wave function |ψ⟩ can be expressed as a linear combination of the {|φn⟩} with complex coefficients:

where cn = ⟨φn|ψ⟩. Complete orthonormal systems of wave functions appear naturally as the eigenfunctions of the Hamiltonian (of a bound system) in quantum mechanics that measures the energy levels, which are called the eigenvalues. The set of eigenvalues, in this case, is known as the spectrum of the Hamiltonian. In bra–ket notation this equality implies the resolution of the identity:

Here the eigenvalues are assumed to be discrete, but the set of eigenvalues of an observable can also be continuous. An example is the position operator, Qψ(x) = xψ(x). The spectrum of the position (in one dimension) is the entire real line and is called a continuous spectrum. However, unlike the Hamiltonian, the position operator lacks proper eigenfunctions. The conventional way to overcome this shortcoming is to widen the class of available functions by allowing distributions as well, i.e., to replace the Hilbert space with a rigged Hilbert space.[95] In this context, the position operator has a complete set of generalized eigenfunctions,[96] labeled by the points y of the real line, given by

The generalized eigenfunctions of the position operator are called the eigenkets and are denoted by φy = |y⟩.[97]

Similar considerations apply to any other (unbounded) self-adjoint operator with continuous spectrum and no degenerate eigenvalues, such as the momentum operator P. In that case, there is a set Ω of real numbers (the spectrum) and a collection of distributions φy with y ∈ Ω such that

That is, φy are the generalized eigenvectors of P. If they form an "orthonormal basis" in the distribution sense, that is:

then for any test function ψ,

where c(y) = ⟨ψ, φy⟩. That is, there is a resolution of the identity

where the operator-valued integral is again understood in the weak sense. If the spectrum of P has both continuous and discrete parts, then the resolution of the identity involves a summation over the discrete spectrum and an integral over the continuous spectrum.

The delta function also has many more specialized applications in quantum mechanics, such as the delta potential models for a single and double potential well.

Structural mechanics

[edit]The delta function can be used in structural mechanics to describe transient loads or point loads acting on structures. The governing equation of a simple mass–spring system excited by a sudden force impulse I at time t = 0 can be written[98][99] where m is the mass, ξ is the deflection, and k is the spring constant.

As another example, the equation governing the static deflection of a slender beam is, according to Euler–Bernoulli theory,

where EI is the bending stiffness of the beam, w is the deflection, x is the spatial coordinate, and q(x) is the load distribution. If a beam is loaded by a point force F at x = x0, the load distribution is written

As the integration of the delta function results in the Heaviside step function, it follows that the static deflection of a slender beam subject to multiple point loads is described by a set of piecewise polynomials.

Also, a point moment acting on a beam can be described by delta functions. Consider two opposing point forces F at a distance d apart. They then produce a moment M = Fd acting on the beam. Now, let the distance d approach the limit zero, while M is kept constant. The load distribution, assuming a clockwise moment acting at x = 0, is written

Point moments can thus be represented by the derivative of the delta function. Integration of the beam equation again results in piecewise polynomial deflection.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Jeffrey 1993, p. 639.

- ^ Arfken & Weber 2000, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Dirac 1930, §22 The δ function.

- ^ a b c Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, Volume I, §1.1.

- ^ Zhao 2011, p. 174.

- ^ Bracewell 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Snieder 2004, p. 212.

- ^ Schwartz 1950, p. 19.

- ^ Schwartz 1950, p. 5.

- ^ Jackson, J. D. (2008-08-01). "Examples of the zeroth theorem of the history of science". American Journal of Physics. 76 (8): 704–719. arXiv:0708.4249. Bibcode:2008AmJPh..76..704J. doi:10.1119/1.2904468. ISSN 0002-9505.

- ^ Laugwitz 1989, p. 230.

- ^ A more complete historical account can be found in van der Pol & Bremmer 1987, §V.4.

- ^ Dirac, P. A. M. (January 1927). "The physical interpretation of the quantum dynamics". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character. 113 (765): 621–641. Bibcode:1927RSPSA.113..621D. doi:10.1098/rspa.1927.0012. ISSN 0950-1207. S2CID 122855515.

- ^ Zee, Anthony (2013). Einstein Gravity in a Nutshell. In a Nutshell Series (1st ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-691-14558-7.

- ^ Fourier, JB (1822). The Analytical Theory of Heat (English translation by Alexander Freeman, 1878 ed.). The University Press. p. [1]., cf. https://books.google.com/books?id=-N8EAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA449 and pp. 546–551. Original French text.

- ^ Komatsu, Hikosaburo (2002). "Fourier's hyperfunctions and Heaviside's pseudodifferential operators". In Takahiro Kawai; Keiko Fujita (eds.). Microlocal Analysis and Complex Fourier Analysis. World Scientific. p. [2]. ISBN 978-981-238-161-3.

- ^ Myint-U., Tyn; Debnath, Lokenath (2007). Linear Partial Differential Equations for Scientists And Engineers (4th ed.). Springer. p. [3]. ISBN 978-0-8176-4393-5.

- ^ Debnath, Lokenath; Bhatta, Dambaru (2007). Integral Transforms And Their Applications (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. [4]. ISBN 978-1-58488-575-7.

- ^ Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (2009). Convolutions in French Mathematics, 1800–1840: From the Calculus and Mechanics to Mathematical Analysis and Mathematical Physics, Volume 2. Birkhäuser. p. 653. ISBN 978-3-7643-2238-0.

- ^

See, for example, Cauchy, Augustin-Louis (1789-1857) Auteur du texte (1882–1974). "Des intégrales doubles qui se présentent sous une forme indéterminèe". Oeuvres complètes d'Augustin Cauchy. Série 1, tome 1 / publiées sous la direction scientifique de l'Académie des sciences et sous les auspices de M. le ministre de l'Instruction publique...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mitrović, Dragiša; Žubrinić, Darko (1998). Fundamentals of Applied Functional Analysis: Distributions, Sobolev Spaces. CRC Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-582-24694-2.

- ^ Kracht, Manfred; Kreyszig, Erwin (1989). "On singular integral operators and generalizations". In Themistocles M. Rassias (ed.). Topics in Mathematical Analysis: A Volume Dedicated to the Memory of A.L. Cauchy. World Scientific. p. https://books.google.com/books?id=xIsPrSiDlZIC&pg=PA553 553]. ISBN 978-9971-5-0666-7.

- ^ Halperin & Schwartz 1952, p. 1.

- ^ Dirac 1930, p. 63.

- ^ Rudin 1966, §1.20

- ^ Hewitt & Stromberg 1963, §19.61.

- ^ Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, Volume I, §1.3.

- ^ Driggers 2003, p. 2321 See also Bracewell 1986, Chapter 5 for a different interpretation. Other conventions for the assigning the value of the Heaviside function at zero exist, and some of these are not consistent with what follows.

- ^ Hewitt & Stromberg 1963, §9.19.

- ^ Billingsley 1986, p. 356.

- ^ Hazewinkel 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Stein & Shakarchi 2007, p. 285.

- ^ Strichartz 1994, §2.2.

- ^ Hörmander 1983, Theorem 2.1.5.

- ^ Schwartz 1950.

- ^ Bracewell 1986, Chapter 5.

- ^ Hörmander 1983, §3.1.

- ^ Strichartz 1994, §2.3.

- ^ Hörmander 1983, §8.2.

- ^ Rudin 1966, §1.20.

- ^ Dieudonné 1972, §17.3.3.

- ^ Krantz, Steven G.; Parks, Harold R. (2008-12-15). Geometric Integration Theory. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-8176-4679-0.

- ^ Federer 1969, §2.5.19.

- ^ Strichartz 1994, Problem 2.6.2.

- ^ Vladimirov 1971, Chapter 2, Example 3(d).

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Sifting Property". MathWorld.

- ^ Karris, Steven T. (2003). Signals and Systems with MATLAB Applications. Orchard Publications. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-9709511-6-8.

- ^ Roden, Martin S. (2014-05-17). Introduction to Communication Theory. Elsevier. p. [5]. ISBN 978-1-4831-4556-3.

- ^ Rottwitt, Karsten; Tidemand-Lichtenberg, Peter (2014-12-11). Nonlinear Optics: Principles and Applications. CRC Press. p. [6] 276. ISBN 978-1-4665-6583-8.

- ^ Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, Vol. 1, §II.2.5.

- ^ Further refinement is possible, namely to submersions, although these require a more involved change of variables formula.

- ^ Hörmander 1983, §6.1.

- ^ Lange 2012, pp.29–30.

- ^ Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, p. 212.

- ^ Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, p. 26.

- ^ Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, §2.1.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Doublet Function". MathWorld.

- ^ Bracewell 2000, p. 86.

- ^ "Gugo82's comment on the distributional derivative of Dirac's delta". matematicamente.it. 12 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Hörmander 1983, p. 56.

- ^ Namias, Victor (July 1977). "Application of the Dirac delta function to electric charge and multipole distributions". American Journal of Physics. 45 (7): 624–630. doi:10.1119/1.10779.

- ^ Rudin 1991, Theorem 6.25.

- ^ Stein & Weiss 1971, Theorem 1.18.

- ^ Rudin 1991, §II.6.31.

- ^ More generally, one only needs η = η1 to have an integrable radially symmetric decreasing rearrangement.

- ^ Saichev & Woyczyński 1997, §1.1 The "delta function" as viewed by a physicist and an engineer, p. 3.

- ^ Milovanović, Gradimir V.; Rassias, Michael Th (2014-07-08). Analytic Number Theory, Approximation Theory, and Special Functions: In Honor of Hari M. Srivastava. Springer. p. 748. ISBN 978-1-4939-0258-3.

- ^ Stein & Shakarchi 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Stein & Weiss 1971, §I.1.

- ^ Mader, Heidy M. (2006). Statistics in Volcanology. Geological Society of London. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-86239-208-3.

- ^ Vallée & Soares 2004, §7.2.

- ^ Hörmander 1983, §7.8.

- ^ Courant & Hilbert 1962, §14.

- ^ John 1955.

- ^ Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, I, §3.10.

- ^ The numerical factors depend on the conventions for the Fourier transform.

- ^ Bracewell 1986.

- ^ Lang 1997, p. 312.

- ^ In the terminology of Lang (1997), the Fejér kernel is a Dirac sequence, whereas the Dirichlet kernel is not.

- ^ Reed & Simon 1980, Ch. II–III, VIII.

- ^ Adams & Fournier 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Hazewinkel 1995, p. 357.

- ^ Zhu 2007, Ch. 4.

- ^ Levin 2002, p. 109.

- ^ Davis & Thomson 2000, p. 343.

- ^ Davis & Thomson 2000, p. 344.

- ^ de la Madrid, Bohm & Gadella 2002.

- ^ Laugwitz 1989.

- ^ Córdoba 1988.

- ^ Hörmander 1983, §7.2.

- ^ Vladimirov 1971, §5.7.

- ^ Hartmann 1997, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Kanwal, Ram P. (1997). "15.1. Applications to Probability and Random Processes". Generalized Functions Theory and Technique. Boston, MA: Birkhäuser Boston. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-0035-9. ISBN 978-1-4684-0037-3.

- ^ Karatzas & Shreve 1998, p. 204.

- ^ Isham 1995, §6.2.

- ^ Gelfand & Shilov 1966–1968, Vol. 4, §I.4.1.

- ^ de la Madrid Modino 2001, pp. 96, 106.

- ^ Arfken & Weber 2005, pp. 975–976.

- ^ Boyce, DiPrima & Meade 2017, pp. 270–273.

References

[edit]- Adams, Robert A.; Fournier, John J. F. (2003). Sobolev Spaces (2nd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-044143-3.

- Arfken, George Brown; Weber, Hans-Jurgen (2005). Mathematical Methods for Physicists. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-088584-0.

- Aratyn, Henrik; Rasinariu, Constantin (2006), A short course in mathematical methods with Maple, World Scientific, ISBN 978-981-256-461-0.

- Arfken, G. B.; Weber, H. J. (2000), Mathematical Methods for Physicists (5th ed.), Boston, Massachusetts: Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-059825-0.

- atis (2013), ATIS Telecom Glossary, archived from the original on 2013-03-13

- Billingsley (1986), Probability and measure (2nd ed.)

- Boyce, William E.; DiPrima, Richard C.; Meade, Douglas B. (2017). Elementary differential equations and boundary value problems. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-37792-4.

- Bracewell, R. N. (1986), The Fourier Transform and Its Applications (2nd ed.), McGraw-Hill, Bibcode:1986ftia.book.....B.

- Bracewell, R. N. (2000), The Fourier Transform and Its Applications (3rd ed.), McGraw-Hill.

- Córdoba, A. (1988), "La formule sommatoire de Poisson", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série I, 306: 373–376.

- Courant, Richard; Hilbert, David (1962), Methods of Mathematical Physics, Volume II, Wiley-Interscience.

- Davis, Howard Ted; Thomson, Kendall T (2000), Linear algebra and linear operators in engineering with applications in Mathematica, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-206349-7

- Dieudonné, Jean (1976), Treatise on analysis. Vol. II, New York: Academic Press [Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers], ISBN 978-0-12-215502-4, MR 0530406.

- Dieudonné, Jean (1972), Treatise on analysis. Vol. III, Boston, Massachusetts: Academic Press, MR 0350769

- Dirac, Paul (1930), The Principles of Quantum Mechanics (1st ed.), Oxford University Press.

- Driggers, Ronald G. (2003), Encyclopedia of Optical Engineering, CRC Press, Bibcode:2003eoe..book.....D, ISBN 978-0-8247-0940-2.

- Duistermaat, Hans; Kolk (2010), Distributions: Theory and applications, Springer.

- Federer, Herbert (1969), Geometric measure theory, Die Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften, vol. 153, New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. xiv+676, ISBN 978-3-540-60656-7, MR 0257325.

- Gannon, Terry (2008), "Vertex operator algebras", Princeton Companion to Mathematics, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1400830398.

- Gelfand, I. M.; Shilov, G. E. (1966–1968), Generalized functions, vol. 1–5, Academic Press, ISBN 9781483262246.

- Halperin, Israel; Schwartz, Laurent (1952). Introduction to the Theory of Distributions. Toronto [Ontario]: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-9132-8.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). - Hartmann, William M. (1997), Signals, sound, and sensation, Springer, ISBN 978-1-56396-283-7.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel (1995). Encyclopaedia of Mathematics (set). Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel (2011). Encyclopaedia of mathematics. Vol. 10. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-4896-7. OCLC 751862625.

- Hewitt, E; Stromberg, K (1963), Real and abstract analysis, Springer-Verlag.

- Hörmander, L. (1983), The analysis of linear partial differential operators I, Grundl. Math. Wissenschaft., vol. 256, Springer, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-96750-4, ISBN 978-3-540-12104-6, MR 0717035.

- Isham, C. J. (1995), Lectures on quantum theory: mathematical and structural foundations, Imperial College Press, Bibcode:1995lqtm.book.....I, ISBN 978-81-7764-190-5.

- Jeffrey, Alan (1993), Linear Algebra and Ordinary Differential Equations, CRC Press, p. 639

- John, Fritz (1955), Plane waves and spherical means applied to partial differential equations, Interscience Publishers, New York-London, MR 0075429. Reprinted, Dover Publications, 2004, ISBN 9780486438047.

- Karatzas, Ioannis; Shreve, Steven E. (1998), Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus, vol. 113, New York, NY: Springer New York, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0949-2, ISBN 978-0-387-97655-6

- Lang, Serge (1997), Undergraduate analysis, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-2698-5, ISBN 978-0-387-94841-6, MR 1476913.

- Lange, Rutger-Jan (2012), "Potential theory, path integrals and the Laplacian of the indicator", Journal of High Energy Physics, 2012 (11) 32: 29–30, arXiv:1302.0864, Bibcode:2012JHEP...11..032L, doi:10.1007/JHEP11(2012)032, S2CID 56188533.

- Laugwitz, D. (1989), "Definite values of infinite sums: aspects of the foundations of infinitesimal analysis around 1820", Arch. Hist. Exact Sci., 39 (3): 195–245, doi:10.1007/BF00329867, S2CID 120890300.

- Levin, Frank S. (2002), "Coordinate-space wave functions and completeness", An introduction to quantum theory, Cambridge University Press, pp. 109ff, ISBN 978-0-521-59841-5

- Li, Y. T.; Wong, R. (2008), "Integral and series representations of the Dirac delta function", Commun. Pure Appl. Anal., 7 (2): 229–247, arXiv:1303.1943, doi:10.3934/cpaa.2008.7.229, MR 2373214, S2CID 119319140.

- de la Madrid Modino, R. (2001). Quantum mechanics in rigged Hilbert space language (PhD thesis). Universidad de Valladolid.

- de la Madrid, R.; Bohm, A.; Gadella, M. (2002), "Rigged Hilbert Space Treatment of Continuous Spectrum", Fortschr. Phys., 50 (2): 185–216, arXiv:quant-ph/0109154, Bibcode:2002ForPh..50..185D, doi:10.1002/1521-3978(200203)50:2<185::AID-PROP185>3.0.CO;2-S, S2CID 9407651.

- McMahon, D. (2005-11-22), "An Introduction to State Space" (PDF), Quantum Mechanics Demystified, A Self-Teaching Guide, Demystified Series, New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 108, ISBN 978-0-07-145546-6, retrieved 2008-03-17.

- van der Pol, Balth.; Bremmer, H. (1987), Operational calculus (3rd ed.), New York: Chelsea Publishing Co., ISBN 978-0-8284-0327-6, MR 0904873.

- Reed, Michael; Simon, Barry (1980). Methods of Modern Mathematical Physics, Volume I: Functional Analysis. Academic Press. ISBN 9780125850506.

- Rudin, Walter (1966). Devine, Peter R. (ed.). Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill (published 1987). ISBN 0-07-100276-6.

- Rudin, Walter (1991), Functional Analysis (2nd ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-054236-5.

- Vallée, Olivier; Soares, Manuel (2004), Airy functions and applications to physics, London: Imperial College Press, ISBN 9781911299486.

- Saichev, A I; Woyczyński, Wojbor Andrzej (1997), "Chapter1: Basic definitions and operations", Distributions in the Physical and Engineering Sciences: Distributional and fractal calculus, integral transforms, and wavelets, Birkhäuser, ISBN 978-0-8176-3924-2

- Schwartz, L. (1950), Théorie des distributions, vol. 1, Hermann.

- Schwartz, L. (1951), Théorie des distributions, vol. 2, Hermann.

- Snieder, Roel (2004), A Guided Tour of Mathematical Methods: For the Physical Sciences, Cambridge University Press

- Stein, Elias; Weiss, Guido (1971), Introduction to Fourier Analysis on Euclidean Spaces, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08078-9.

- Strichartz, R. (1994), A Guide to Distribution Theory and Fourier Transforms, CRC Press, ISBN 978-0-8493-8273-4.

- Vladimirov, V. S. (1971), Equations of mathematical physics, Marcel Dekker, ISBN 978-0-8247-1713-1.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Delta Function". MathWorld.

- Yamashita, H. (2006), "Pointwise analysis of scalar fields: A nonstandard approach", Journal of Mathematical Physics, 47 (9): 092301, Bibcode:2006JMP....47i2301Y, doi:10.1063/1.2339017

- Yamashita, H. (2007), "Comment on "Pointwise analysis of scalar fields: A nonstandard approach" [J. Math. Phys. 47, 092301 (2006)]", Journal of Mathematical Physics, 48 (8): 084101, Bibcode:2007JMP....48h4101Y, doi:10.1063/1.2771422

- Zhao, Ji-Cheng (2011), Methods for Phase Diagram Determination, Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-08-054996-5

- Zhu, Kehe (2007). Operator Theory in Function Spaces. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs. Vol. 138. American Mathematical Society.

External links

[edit] Media related to Dirac distribution at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dirac distribution at Wikimedia Commons- "Delta-function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- KhanAcademy.org video lesson

- The Dirac Delta function, a tutorial on the Dirac delta function.

- Video Lectures – Lecture 23, a lecture by Arthur Mattuck.

- The Dirac delta measure is a hyperfunction

- We show the existence of a unique solution and analyze a finite element approximation when the source term is a Dirac delta measure

- Non-Lebesgue measures on R. Lebesgue-Stieltjes measure, Dirac delta measure. Archived 2008-03-07 at the Wayback Machine

![{\displaystyle \Delta t=[0,T]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f9e2d96fc8758cc490227383eb4eadb234578795)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}f(x)&={\frac {1}{2\pi }}\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }e^{ipx}\left(\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }e^{-ip\alpha }f(\alpha )\,d\alpha \right)\,dp\\[4pt]&={\frac {1}{2\pi }}\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\left(\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }e^{ipx}e^{-ip\alpha }\,dp\right)f(\alpha )\,d\alpha =\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\delta (x-\alpha )f(\alpha )\,d\alpha ,\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/656c821d528199232d832d301bbec290a815fe63)

![{\displaystyle H(x)=\int _{\mathbf {R} }\mathbf {1} _{(-\infty ,x]}(t)\,\delta (dt)=\delta \!\left((-\infty ,x]\right),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9a67b29a323434685200c36791fa963803be0c31)

![{\displaystyle \delta [\varphi ]=\varphi (0)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/df9006764a21dbc1593891d76b94e4a6c13cdd06)

![{\displaystyle \left|S[\varphi ]\right|\leq C_{N}\sum _{k=0}^{M_{N}}\sup _{x\in [-N,N]}\left|\varphi ^{(k)}(x)\right|}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a8921d57621545fc5640742ebe3f0a611bfd5998)

![{\displaystyle \delta [\varphi ]=-\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\varphi '(x)\,H(x)\,dx.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5d867f4262298fa1f65e8b5ddc95df0f4d509f4a)

![{\displaystyle \delta _{x_{0}}[\varphi ]=\varphi (x_{0})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9219b75c2a59f85c4a495187a42b9f997c7547a9)

![{\displaystyle \delta \left(x^{2}-\alpha ^{2}\right)={\frac {1}{2|\alpha |}}{\Big [}\delta \left(x+\alpha \right)+\delta \left(x-\alpha \right){\Big ]}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d6570a1d3ae92889f1cb92ad03121ad1ef10acd1)

![{\displaystyle \delta _{S}[g]=\int _{S}g({\boldsymbol {s}})\,d\sigma ({\boldsymbol {s}})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8d0759b7b4d698e108b006b83385cb19a2048002)

![{\displaystyle \delta '[\varphi ]=-\delta [\varphi ']=-\varphi '(0).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6dcbd7eb8726c02cb50a897f5d3ae2fdc88ad3d0)

![{\displaystyle \delta ^{(k)}[\varphi ]=(-1)^{k}\varphi ^{(k)}(0).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/92b8ca88b17041c8f71580ab9779320dfddadb28)

![{\displaystyle (\tau _{h}S)[\varphi ]=S[\tau _{-h}\varphi ].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/da7641428f61e4c1de41526c105208eccffd83eb)

![{\displaystyle \delta _{a}[\varphi ]=\varphi (a)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ae820065c43b667f4247c78672dcd2f83fa79316)

![{\textstyle \left[-{\frac {1}{2}},{\frac {1}{2}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/19b64dd6fad3e022e8b3d9f606a2a42292c6181e)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{cases}{\dfrac {\partial }{\partial t}}\eta (t,x)=A\eta (t,x),\quad t>0\\[5pt]\displaystyle \lim _{t\to 0^{+}}\eta (t,x)=\delta (x)\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2dcd8145e7871cf48f317c1c4d935ac7eb468604)

=|2\pi \xi |{\mathcal {F}}f(\xi ).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a9dba5209bfdb79796ee7978fbc154e029212b62)

![{\displaystyle L[u]=f,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/074535ba6bdba1d73b1f0bdb8cde6be6f06d1d6c)

![{\displaystyle L[u]=\delta .}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6306e66d605d9cde6ddf5b7f85302c2aa915dcd7)

![{\displaystyle L[u]=h}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d0a532cf7d2fd63a65144c98a7bbf8456eceaf91)

![{\displaystyle g(s)=\operatorname {Re} \left[{\frac {-s^{k}\log(-is)}{k!(2\pi i)^{n}}}\right]={\begin{cases}{\frac {|s|^{k}}{4k!(2\pi i)^{n-1}}}&n{\text{ odd}}\\[5pt]-{\frac {|s|^{k}\log |s|}{k!(2\pi i)^{n}}}&n{\text{ even.}}\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3fb36840bedf496b8822ad586804f91ae10fcba1)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&c_{n}\Delta _{x}^{\frac {n+1}{2}}\iint _{S^{n-1}}\varphi (y)|(y-x)\cdot \xi |\,d\omega _{\xi }\,dy\\[5pt]&\qquad =c_{n}\Delta _{x}^{(n+1)/2}\int _{S^{n-1}}\,d\omega _{\xi }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }|p|R\varphi (\xi ,p+x\cdot \xi )\,dp\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d7bb9fbfb3720307465949837a5c76ae4a649295)

![{\displaystyle \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }e^{i2\pi \xi _{1}t}\left[e^{i2\pi \xi _{2}t}\right]^{*}\,dt=\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }e^{-i2\pi (\xi _{2}-\xi _{1})t}\,dt=\delta (\xi _{2}-\xi _{1}).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8007cb6fa52a213211396ce15fa16d836540ab0c)

![{\displaystyle \delta [f]=|f(0)|<C\|f\|_{H^{1}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4d546155e53e1d2a324b2639790b8845db523fca)

![{\displaystyle \delta _{z}[f]=f(z)={\frac {1}{2\pi i}}\oint _{\partial D}{\frac {f(\zeta )\,d\zeta }{\zeta -z}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/35176ad52679bd943137c4ab9d002ad92a8c4dea)

![{\displaystyle \delta _{w}[f]=f(w)={\frac {1}{\pi }}\iint _{|z|<1}{\frac {f(z)\,dx\,dy}{(1-{\bar {z}}w)^{2}}}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4107a6750747d8aad60c24262e3c1bc56d9f9e4b)

![{\displaystyle \ell (x,t)=\lim _{\varepsilon \to 0^{+}}{\frac {1}{2\varepsilon }}\int _{0}^{t}\mathbf {1} _{[x-\varepsilon ,x+\varepsilon ]}(B(s))\,ds}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5559ee5dae6a003812081e6f4785fe97c5c7ce3e)

![{\displaystyle \mathbf {1} _{[x-\varepsilon ,x+\varepsilon ]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5d2638b50ca5e6ffd77a1e6e4747b7b98c5b786f)

![{\displaystyle [x-\varepsilon ,x+\varepsilon ].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ee3e4409bd7fe914f16bb104c11de59e5ee1a225)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}q(x)&=\lim _{d\to 0}{\Big (}F\delta (x)-F\delta (x-d){\Big )}\\[4pt]&=\lim _{d\to 0}\left({\frac {M}{d}}\delta (x)-{\frac {M}{d}}\delta (x-d)\right)\\[4pt]&=M\lim _{d\to 0}{\frac {\delta (x)-\delta (x-d)}{d}}\\[4pt]&=M\delta '(x).\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bd72d95be9328aeeea207fd8a970c1bdd5304b56)